We often think of musicals—whether on stage or screen—as vehicles for catchy tunes and flashy dance numbers. These productions, however, are far more than entertainment. Rather, musicals convey specific knowledge, teaching us about their locales and the people who occupy them. This premise underlies “Understanding Urban Landscape through Art and Musicals,” a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) J-Term course taught by Trinity Kao (MAUD ’25). Each year prior to the spring semester, GSD students, faculty, and staff are invited to teach non-graded workshops that explore unique, experimental topics. In her J-Term course, Kao positions musicals alongside photographs, paintings, and other works of art as intimately tied to their cultural contexts.

Growing up in Taiwan, Kao was drawn to musicals because they offered insight into American culture, especially the urban environments in which musicals often take place. While maps may delineate district boundaries, street locations, and building adjacencies, musicals offer more nuanced information. The musical West Side Story, for example, conveys the racial tensions that pervaded 1950s Upper West Side Manhattan, alongside the neighborhood’s characteristic fire escapes, roof tops, and highway underpasses. By watching even a portion of the musical, we can quickly acquire a sense of the cultural and physical environment of the particular time and place. And significantly, as Kao notes, “the musical is a form of media understandable by everyone,” no special training required.

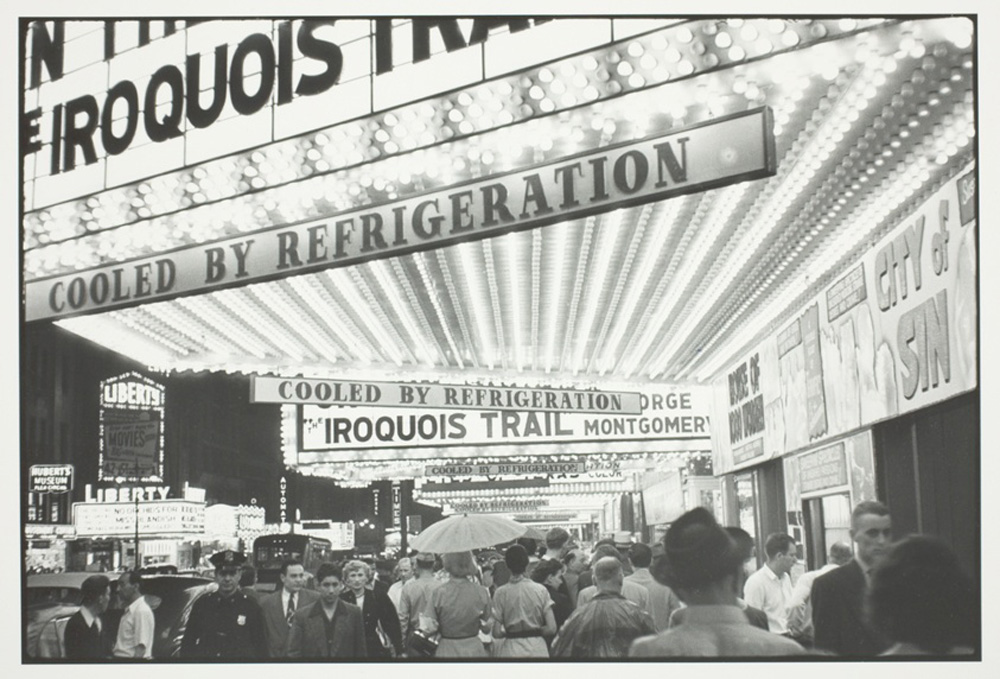

Throughout the course, in total three 90-minute sessions, Kao introduces nearly a dozen musicals, including Legally Blonde, Little Shop of Horrors, In the Heights, and 42nd Street. The preponderance of musicals that Kao discusses take place in New York City or Los Angeles, save for a few outliers such as Hairspray (Baltimore); Oklahoma (Oklahoma City, Nebraska), and Waitress (the American South). Speaking of American musicals, Kao points out that, while none are situated in Santa Fe, both Newsies and Rent contain songs about the New Mexico city, fashioning it as a utopian respite from urban chaos.

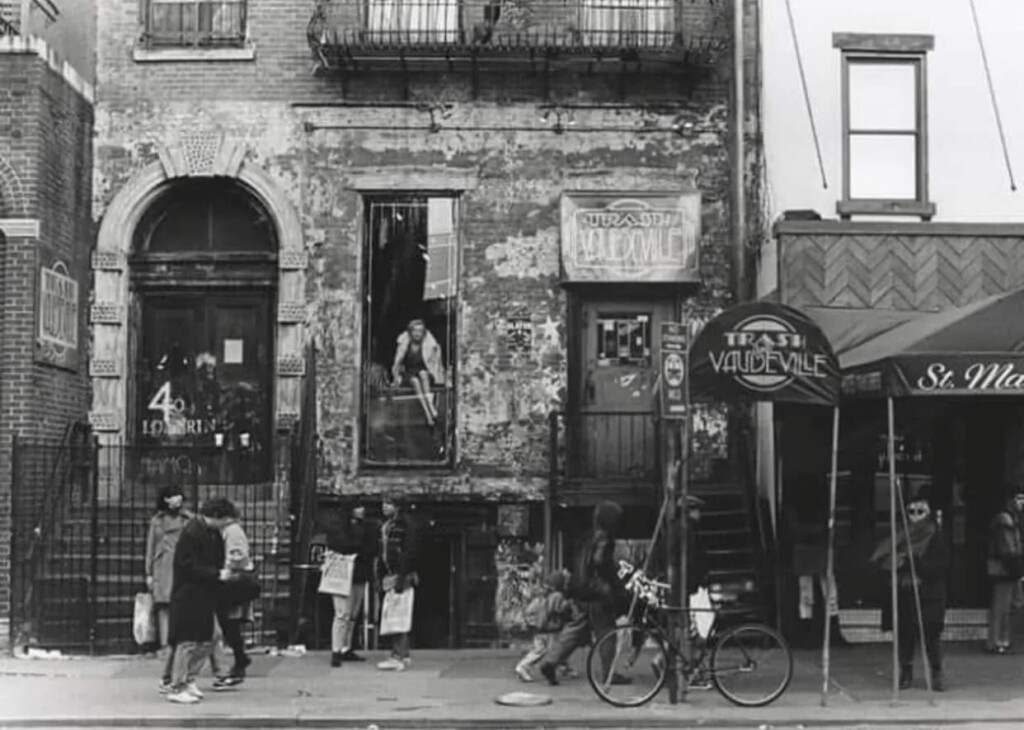

Indeed, the notion of utopia markedly contrasts with the difficult lives described in productions such as Rent. Opening on Broadway in 1996, Rent echoes Puccini’s opera La Bohème (1896), which focuses on a group of poor artists in the Parisian Latin Quarter circa 1830. A late twentieth-century interpretation of its predecessor, Rent relocates the action to Manhattan’s Lower East Side (East Village), a ramshackle neighborhood-turned-haven for Bohemians facing the myriad pressures of poverty, gentrification, and the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s. No map could convey the predicament faced by the musical’s characters, squatters in a derelict apartment, who amid winter’s bitter chill rely on indoor bonfires for warmth and candles for light. Nor could a map communicate the avarice behind the developer-driven scheme to redevelop this property, despite displacing the struggling artists and the unhoused people who live on the lot next door.

In such a manner, musicals have the power to illuminate the lived experience of a city at a specific moment in time. Simultaneously, their adaptations underscore continuities throughout time. Elaborating on Rent and La Boheme, Kao notes that, despite the hundred years that separate the two stories, “we see the same kind of people living in the two cities. These people have the same kinds of dreams, the same types of struggles, even as the urban structure keeps changing.” Musicals, then, not only teach us about cities; they elucidate enduring aspects of the human condition.

Photo Credits

West Side Story: ©Disney.

Faurer, Indian Summer: Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, transfer from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Copyright © Estate of Louis Faurer. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

East Village: Photographer unknown. https://medium.com/@michaelcline2323/saint-marks-place-east-village-nyc-a08600b29b66.