This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon, a time An-My Lê remembers vividly. As she recalled during her Rouse Visiting Artist Lecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) this month, Lê and her family were among the hundreds evacuated from Vietnam by US soldiers. When she left, she was just fifteen years old, and, because of the war, had never had access to the Mekong Delta. Her only memories of the place were images she’d seen of GI’s being airlifted out. Nearly twenty years later, working under a grant after graduate school, she went back to photograph it.

“Exploring the landscape was a complete adventure,” said Lê, describing her return in 1994, when the United States re-established relations with Vietnam. “Living in exile,” she explained, “means not having access to your culture. For many years, we did not think we could return to Vietnam, and once I got there, I realized that all these memories were not very reliable.”

Speaking at the GSD on April 1, Lê described how she made repeated visits to make landscape photographs with a view camera. The cumbersome but essential tool allows her to capture vast landscapes and poignant portraits, with long exposures that often create “happy accidents.” Back in Vietnam, she quickly found resonances of not only her childhood and the war, but also centuries past emerging in her images. The blurry palm trees above a flock of ducks, depicted in “Untitled, Mekong Delta, 1994,” could have been preserved from another lifetime, long before the war made travel in the Mekong Delta unsafe and damaged the landscape.

Lê pointed out the similarity between her work as a photographer and that of landscape architects in terms of time and history. Landscape architects design spaces we experience in the moment that also make reference to history and suggest potential change. According to Lê, photographers layer their images with “notions of the past” and future. She said she looks at the landscape like a designer when she thinks about the separation between earth and sky, or questions of scale.

“I love the freedom,” she said of her medium. “You can start anywhere. And yet, we do our best to provide specific elements—whether a landscape architect designs a particular hill or curve, or how I choose to frame an image—but, the final experience is something we can’t control.”

In 1999, at the invitation of a group of Vietnam War reenactors who stage battles in Virginia and North Carolina, she began to photograph images of war—or at least, a mimicry of it. She often participated in the events herself so that she could remain close to the action, posing as a spy or soldier. The resulting images—a cluster of soldiers converging in a small opening in the woods blurred by a stand of bamboo they’d planted, the sparks of a bomb splashing into the air like a fountain—reveal the moments she found most interesting, which, she reminded the audience, is not the same as the photojournalistic impulse to record what’s “most pressing.”

Since then, she has observed military trainings in the Southern California desert that prepared soldiers for the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, traveled on US navy ships across the Pacific, visited army training sessions in Ghana, and observed earthquake relief efforts in Haiti. Images from these travels became part of her series “29 Palms” (2003) and “Events Ashore” (2005–2012). She has also continued to attend war reenactments and was invited to shoot at the Louisiana filming of Free State of Jones, about the Civil War. While she often pursues “hot button topics,” she approaches those issues not from a documentary perspective but with poetic language, explaining that the building blocks of language and the photographic worlds she creates are very similar in terms of establishing tension, perspective, and the marriage of form and content.

In 2022, Lê began to experiment with the cyclorama, a form popular before the moving image that surrounded viewers with monumental paintings on the walls of a circular room. She reimagined the genre by hanging a series of large-scale photographs side by side around a circular room, allowing people to read them in linear and nonlinear fashions.

She used the cyclorama to present narrative photographs in the 2024 series “Dark Star” and “Grey Wolf.” Shot at a national park in Colorado near a nuclear missile test site, the images in “Dark Star” depict the vast night sky, capturing with a long exposure the thousands of stars invisible to the naked eye, and urging the viewer to consider “civilization and the infinite world beyond us”—perhaps even offering comfort, Lê explained. “Grey Wolf,” a series of photographs shot from a helicopter over the missile installations set amid farmland in Montana and Nebraska, was inspired in part by the history of Land Art. The sites and their context evoke the monumental earthworks and concrete structures that comprise artist Michael Heizer’s Nevada project City, which stretches across over a mile of the desert. “The size of the stones on the path, the color of the stones, the height of the sidewalk, the borders, the plants—it’s very specific.” Lê cites Heizer as a contemporary influence.

She also engages deeply with the history of her primary medium and acknowledges nineteenth-century war photographers Timothy O’Sullivan and Roger Fenton as influences as well. Because war and its aftermath has been her subject for much of her career, Lê has had to wrestle with the question of whether she’s rendering violence “beautiful.” Her landscape photographs have been compared to the work of Robert Adams, and challenge our perception of the narrative a war image can tell. She argued that she’s in search of something beyond beauty—the sublime, or ineffable.

Her use of the view camera helps advance that goal. While she tried a smaller camera that allowed her to move with more agility, she was dissatisfied with the images; cumbersome though the view camera was, it allowed her to capture the landscape as she perceived it, with its many layers of space, time, and the valances of memory. And as she experimented with portrait photography—for example in her portraits of women on the carrier ships in “Events Ashore”—she also found that the view camera created different experiences with her subjects. When she went under the dark curtain to snap the shot, people posed for the camera, looking into its lens but unable to see her looking back.

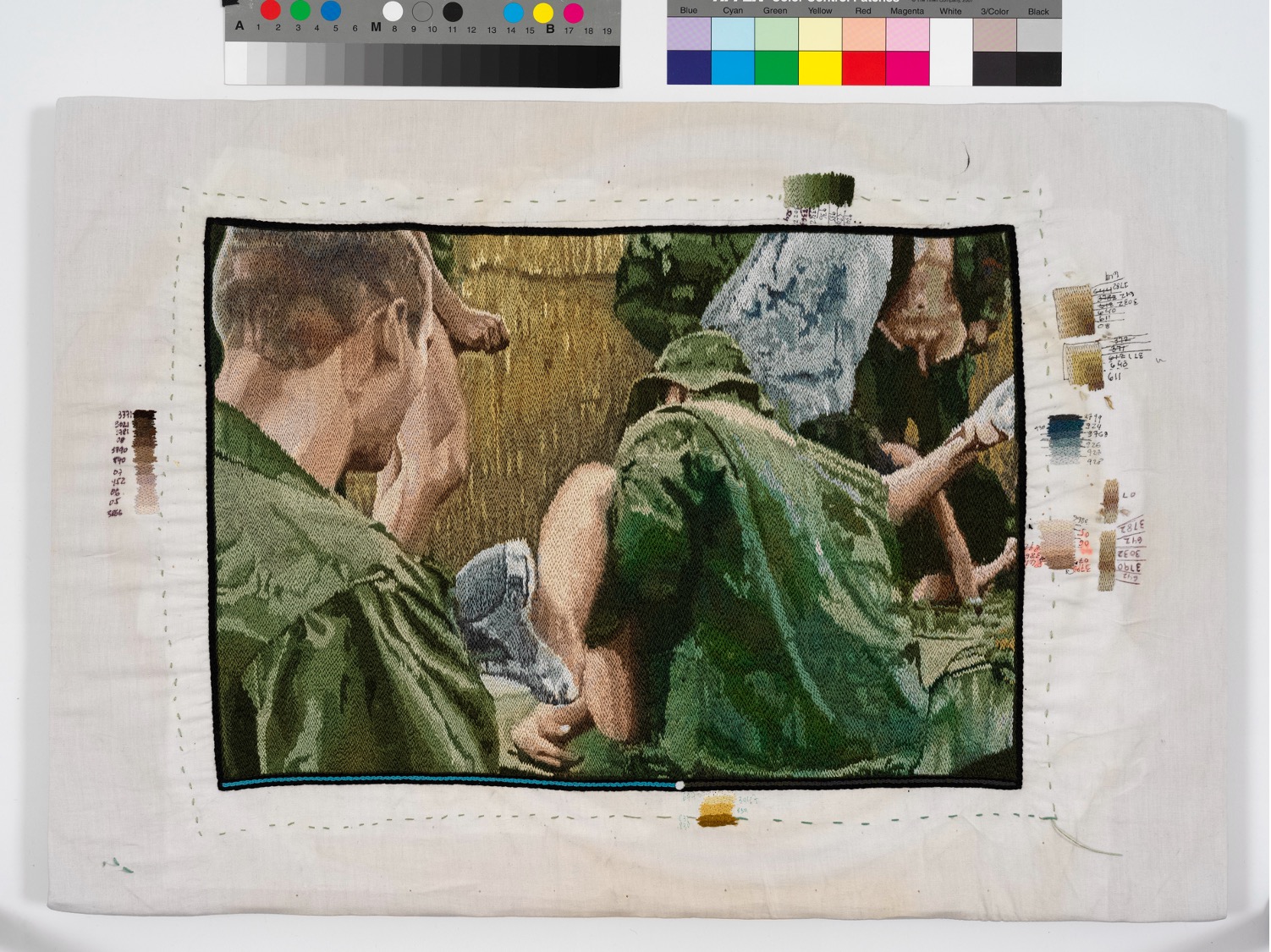

Lê concluded her talk at the GSD with discussion of recent work in a new medium, embroidery, in which she considers the “ecstatic sublimity and quasi-religiosity of the frenzied performance.” She creates embroideries based on stills from a pornographic movie ostensibly set during the Vietnam War, in which performers stage an encounter between American soldiers and Vietnamese sex workers. She explained that she’s drawn to needlework because it completely absorbs her attention. “I find comfort when I lose myself in the work.”

She previously made weavings for her “đô-mi-nô” series, and was drawn to embroidery after finding a cross-stitched landscape in the basement of her apartment building. In Lê’s printing process, she edits her photographs at the level of the pixel, and began to think, “maybe that’s the way for me to control the image.” She was also influenced by medieval tapestries that “hang as decorative pieces while also suggesting a narrative. They’re about storytelling.”

Inspired by the long tradition of embroidery in Vietnam, Lê and her studio assistants create painterly palettes for the images that Lê expanded and cropped, abstracting them beyond the pornographic realm. “It’s not easily decipherable at first,” she explained. “I chose moments when the action is more obscure, which was important to get people to stop and think about the origin of the piece.” For her, the series is about how women “hustled during the war,” as well as the “spoils of war,” sex workers, and how the makers of the Vietnam War–themed porn film took a historic and painful time and turned it into entertainment.

Like all of her work, however, she leaves the embroidered images up to the audience to interpret. “Ultimately, you provide an experience that only the audience or the viewer or participant can experience themselves, and you just have to let go.”