Students in Rahul Mehrotra’s “Extreme Urbanism Mumbai” Graduate School of Design (GSD) Spring 2025 option studio faced a challenge that was intended to take them “completely outside their comfort level,” said Mehrotra. “We set a wicked problem that exposes them to an unfolding of interconnected issues.”

Mumbai, set on a peninsula on the northwest coast of India, is one of the largest and densest cities in the world, with a population of about 21.3 million residents and more than 36,200 people per square kilometer—most of whom face a stark housing crisis. Approximately 57 percent of Mumbai’s population lives in informal homes, many of whom work in nearby housing complexes where they’re employed by the upper-class residents. Most of the students in the studio had never been exposed to what Mehrotra describes as “extreme conditions, in terms of density, poverty, and the juxtaposition of different worlds in the same space.”

“Mumbai is like nothing I’d ever seen before,” said Enrique Lozano (MAUD ’26), who had previously traveled to other parts of India. “There’s no designed urban form; skyscrapers are scattered throughout the city. It’s on a former wetland, so there are issues with water, one of my research areas.”

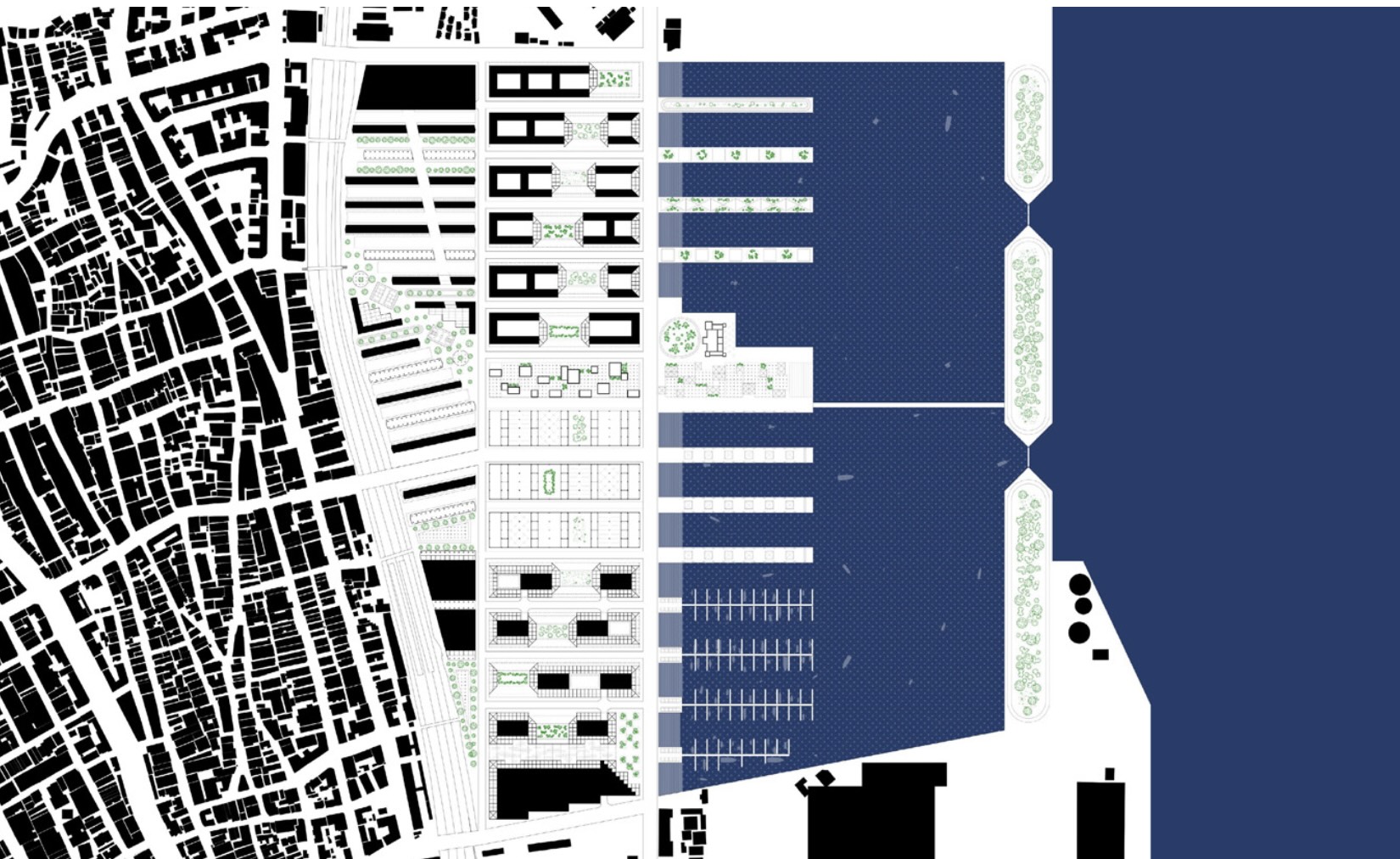

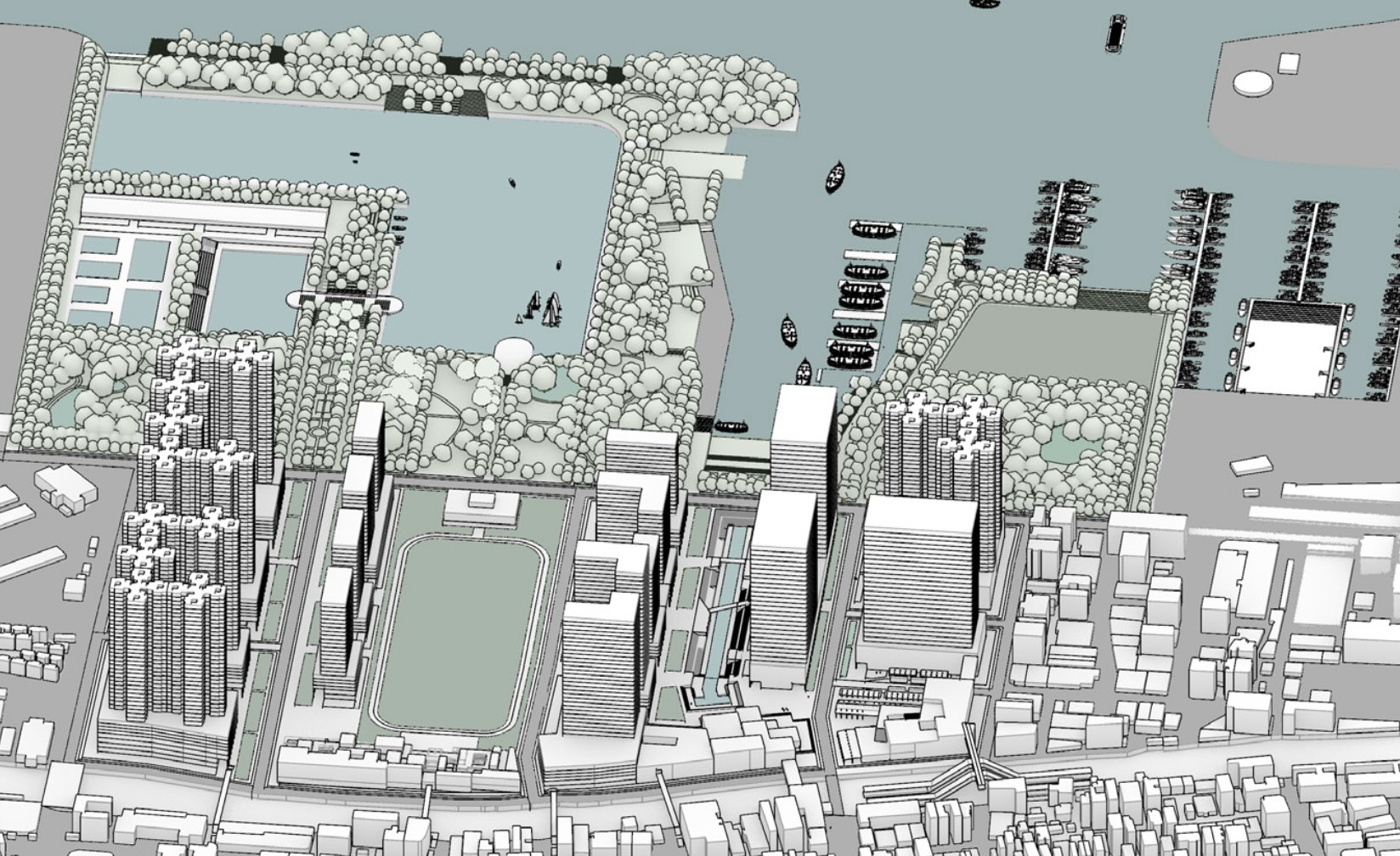

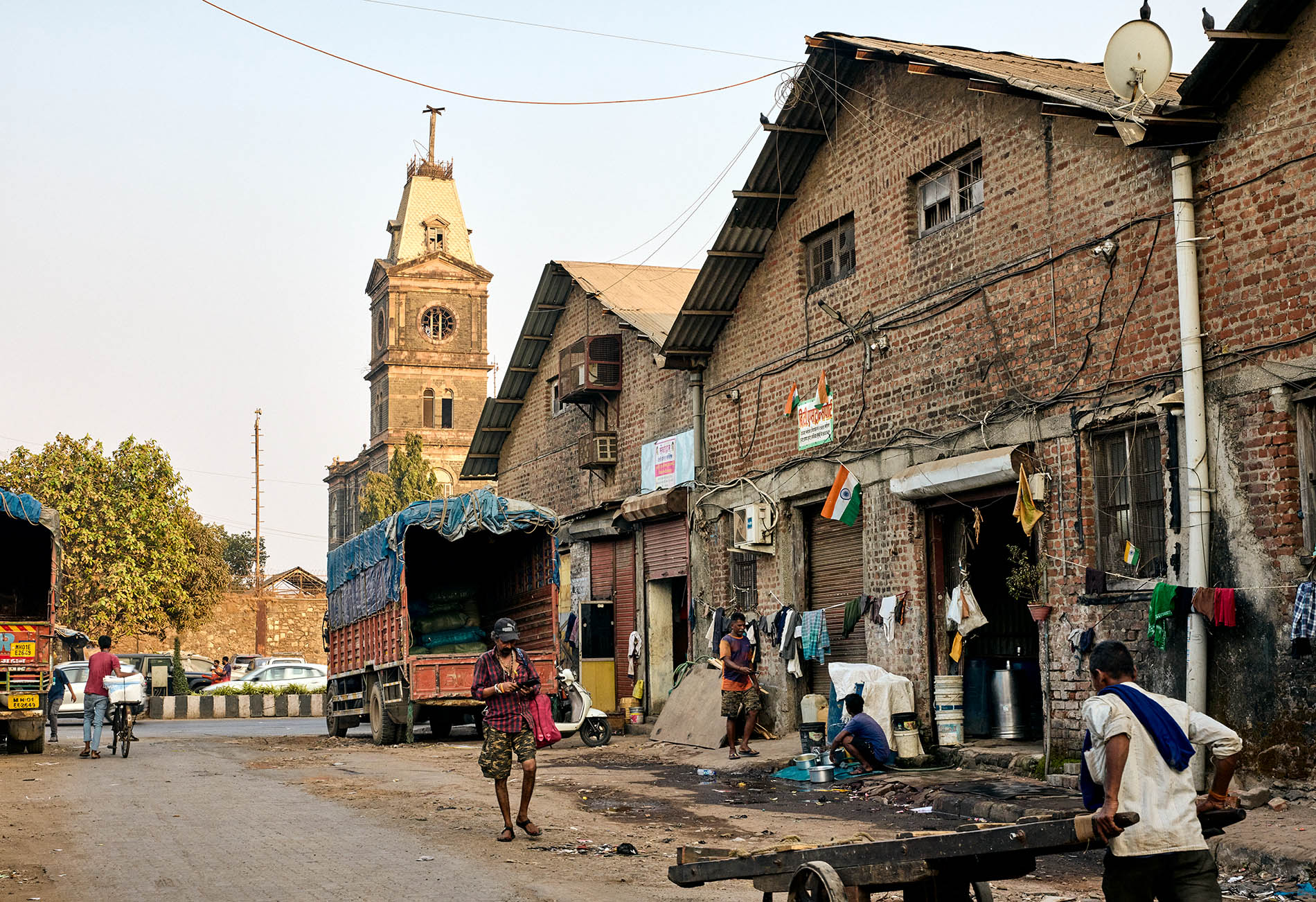

He and his classmates were introduced to Mumbai’s coastal Elphinstone Estate neighborhood and a site owned by the Port Authoritiy of Mumbai that includes 40 acres of warehouses as well as iron and steel shipping offices, bounded on one side by a rail line and on the other by the harbor and P D’Mello Road, a major city street. “The Eastern Waterfront will be one of the city’s most contested land parcels to be opened for urban development in the next few years,” writes Mehrotra. “It plays a catalytic role in connecting the city back to the metropolitan hinterland….” The 900 or so people who work in this area and live in sidewalk tenements stand to be displaced once development progresses.

Elphinstone Estate — the site of the studio

Students were tasked with working at three scales: regional, district (the “superblock”), and site (urban development policy). Rather than displacing workers whose lives are strongly rooted in the neighborhood, students were asked to invent schemes that would newly house those 900 families in tenements by “cross-subsidizing from market-value housing.” The studio offered a counterpoint to the government’s designation of the site as a commercial district. Students’ proposals served what Mehrotra terms in reference to his research, “instruments of advocacy,” creating a way to keep the city’s most vulnerable residents where they have always lived, while also offering needed market-value homes.

This studio differs from many others at the GSD, in that it involves collaboration between the studio and a Master in Real Estate course titled “The Development Project.” Jerold Kayden, Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design and founding director of the Master in Real Estate Program, and Mehrotra brainstormed about the idea of such a collaboration and launched the idea in spring 2024. David Hamilton, a real estate faculty member at the GSD, co-instructed this year’s version in the spring 2025 semester.

“I think of real estate as the physical vessel in which people live, work, and play,” Kayden explained. “And if we can apply our multidisciplinary skills and knowledge to shape real estate in ways that create a more productive, sustainable, equitable, and pleasing world, then I can’t think of a more noble cause than that.”

The magic of the combined studio and real estate class, as Kayden, Mehrotra, and Hamilton saw it, was that students from the two programs would be interdependent and could only solve the on-site housing challenges by working together. “The real estate students couldn’t own the problem because the designers didn’t design it in a way that would work in terms of real estate sense,” said Mehrotra. “And the designers couldn’t think of the design unless the real estate folks came up with a model of financing for that cross-subsidy.”

Hamilton concurred that the studio set up a collaborative tension that replicated real-world challenges: “We can imagine a path that gets us from having bright ideas and a beautiful piece of land, to a proposed future that’s both appealing and realistic enough to attract investment capital to be built. Then, we get to what we call stabilization, where the new neighborhood is working physically and financially in a sustainable way. Getting there involves a million different variables, from government action and public subsidies, to the needs of the market and investors and other financial considerations.”

Lozano saw the benefits of designing in Mumbai, where “the street is an even playing ground. Everybody takes the metro, walks the Plaza, buys street food in the markets.” At the same time, like most collaborators, his group had their share of challenges as they moved through the design process. “The entire studio was a negotiation between the students—of judging our values and understanding that the real estate students want to make a return on investment, but the subversion is the social mission, and the designers had to convince them that social space is an asset.”

He described a beautiful 19th-century clock tower on the Elphinstone site, which one of his real estate group members wanted to demolish, and how they negotiated the “iterative design process” and “pushed against the blank slate idea.” They kept the clock tower, which they saw as a cultural asset, and “turned it into an incredible public amenity with restrooms, civic spaces, and movie screenings. It’s an anchor and memory of the site itself, with the maritime history and labor organizing that occurred there.” Through the collaborative process, building trust by drawing and talking through their design plans, the design students developed a final project of which they’re proud.

“As we become surrounded by the madness and complexities of the world we inhabit,” said Mehrotra, “it’s important to have multiple perspectives on the same problem, and to synthesize those multiple perspectives into a proposition.”

The final review mirrored the lively discourse the students experienced all semester, as critics discussed the merits of each proposal and the possibilities for the Elphinstone Estate. Sujata Saunik, Chief Secretary of the Government of Maharashtra, participated throughout the final review and helped bring to the conversation a sense of Mumbai’s realities. As the student groups together advocated for shared public access to the site and investing in dignified housing for people living in tenements, they presented to the government a more equitable approach to developing a site that’s unique as well as profitable.

“It’s not the solution,” said Mehrotra, “but it’s a conversation changer.”

Student Propositions