Dr. Rachel Weber brings a distinctive perspective to urban planning at a moment when cities worldwide face unprecedented political, environmental, and financial challenges. Appointed Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design effective July 1, 2025, Dr. Weber has a wealth of experience as an urban planner, political economist, and economic geographer and was a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1998. Since joining the GSD as Professor of Urban Planning in January 2025, she has been energized by the school’s dedication to tackling real-world urban problems with analytic rigor and cross-disciplinary collaboration.

Dr. Weber’s scholarly accomplishments are as impressive as they are influential. She is the author of more than 50 peer-reviewed articles, multiple book chapters and reports, and the award-winning book From Boom to Bubble: How Finance Built the New Chicago. Her thought leadership has shaped both academic discourse and urban policy. She has served on advisory committees for planning agencies, community organizations, and political campaigns, and was appointed to President Obama’s Urban Policy Committee. Dr. Weber’s acclaimed body of research explores the often-hidden relationships between financial markets and the built environment, investigating how municipal and private sector borrowing, spending, and development are transformed by the global trading of complex instruments and assets.

As she steps into her new role, we spoke with Dr. Weber about her path to the GSD, the pressing challenges facing today’s cities, and her aspirations for the next generation of urban thinkers and leaders.

CAN YOU SHARE A BIT ABOUT YOUR PROFESSIONAL JOURNEY AND WHAT LED YOU TO URBAN PLANNING?

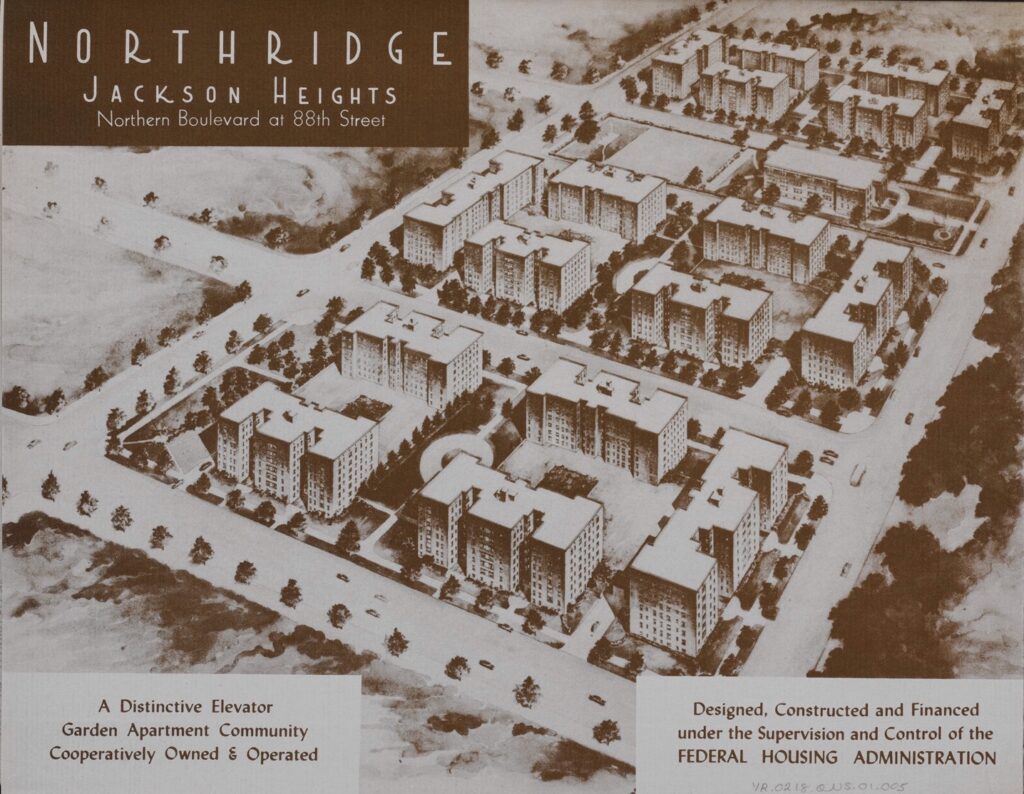

I grew up in Connecticut, although most of my extended family lived in New York City, in Jackson Heights in Queens. New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s was raw, cacophonous, and still clawing its way back from the fiscal crisis of 1975. Garbage was piled up on the street. Vacant storefronts lined Northern Boulevard. There was a two-day blackout in 1977. But I was enamored of the energy and the possibilities for self-expression that the city offered.

On weekends, we would drive to the city to visit our relatives. My father would often take my siblings and me into Manhattan by subway and drop us off at a random intersection. He would tell us to meet him back at that spot in a few hours. Then we would scatter. I don’t remember where my brother and sister went, but I would seek out record stores, thrift shops, and art galleries, anything offbeat and countercultural enough to help me forget I was just a suburban teenager.

I honed my skills of observation and data collection through this urban orienteering. Before smartphones, you found stores you liked by reading fanzines, spotting tear-off ads, and talking to strangers. Before Google Maps, you identified your own landmarks to navigate back to the designated meeting point. I learned how to use my senses to quickly perceive the subtle feeling of a place. I started noticing why some places looked (or smelled or sounded) different from others, which brought me into contact with design and planning.

These weekend adventures left me with a good sense of direction (which I’m finding useless here in Cambridge!) as well as strong opinions about well-designed public places. They also sensitized me to the physical signs of uneven development, which is what continues to drive my interest in urban planning.

IN YOUR VIEW, WHAT’S THE MOST CRITICAL INGREDIENT FOR CREATING MEANINGFUL POLICY CHANGE?

I really appreciate how the academic practice of urban planning creates avenues for political engagement. During my almost three decades of living and working in Chicago, I was asked to give testimony in state legislatures, write affidavits for lawsuits, and serve as an advisor for elected officials and political candidates. I wish there were one ingredient for affecting policy change, but I’ve found it’s more of a stew, or perhaps an even more apt metaphor is a multidimensional game of chess, given how strategic all the actors are.

As an academic, you certainly need to bring the receipts—objective evidence of empirical effects—to the table. Many of us do policy-oriented research, which usually involves some kind of evaluative or prospective analysis of a specific intervention using all available data.

But researchers generally stop when they have findings—for example, “my research shows a positive relationship between this infrastructural improvement and, say, property values.” Creating change and implementing policy reforms requires using these findings to tell a compelling story for why the plan or policy is worth or not worth the effort. Stories help stakeholders see alternative futures, which is why, even for a more numbers-focused person like myself, visualizations are so important. You also need to know which players have power (networks, capital) and to invest in relationships with them and with organizations that will reinforce your story.

Convincing a political representative or government agency to act requires making a case for an issue’s urgency, showing how it aligns with other (sometimes unrelated) goals, and identifying a dedicated funding source. Political engagement is not for the faint of heart, but can be very gratifying. You get to see years of research and advocacy result in policy changes that make a city’s revenue structure more fair, or new investment in places that have been left behind.

WHAT EXCITES YOU MOST ABOUT LEADING THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN PLANNING AND DESIGN?

The Department of Urban Planning and Design, which includes our new Master in Real Estate degree program, bridges three interrelated fields of urbanism that are each critical to the future of cities, yet are rare to see hosted in a single department. Each of our three degree programs shines on its own, but they are better together. I love how students are encouraged to take classes in the other programs and across the GSD. And I love the GSD’s studio pedagogy because it takes a problem orientation instead of a disciplinary one.

Urbanism is innately interdisciplinary. Fidelity to the disciplines can lead to turf wars and to good ideas that are not easy to implement because, say, a financially feasible development project ignores its spatial context or the history of political activism in the neighborhood. Nothing makes me happier than seeing a data scientist, community activist, engineer, and designer—all of them GSD students—standing around their trays puzzling over what to do with a vacant industrial site in a strategic location.

Our intellectually rich set of course offerings not only prepares students for jobs in the field, it also pushes them to think critically about their practice. Students learn about the development process, real estate finance, and site planning. They acquire marketable skills like spatial visualization and policy analysis, but they also engage with sociological and aesthetic theory. They learn how to make persuasive arguments and defend their values.

I’m also excited to work with my faculty colleagues. They are the best in their respective fields and, like me, interested in this kind of interdisciplinary bridging work. They work across the subdisciplines of urbanism and also bridge the worlds of academia and practice. In addition to their research, they run their own design firms, collaborate with governments around the world, and sit on nonprofit boards and government committees. We are supported by a great group of administrators and staff who answer student questions and design exciting programming for them outside the classroom. I am excited to lead a department that delivers excellence on so many levels.

IN THE GSD ANNOUNCEMENT OF YOUR APPOINTMENT, YOU NOTE THAT “PLANNERS, DESIGNERS, AND DEVELOPERS CONFRONT URBAN PROBLEMS IN INCREASINGLY COMPLEX AND POLARIZED ENVIRONMENTS . . . THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN PLANNING AND DESIGN EQUIPS OUR GRADUATES FOR THE TECHNICAL AND ETHICAL CHALLENGES OF BUILDING SHARED SPATIAL FUTURES.”

WHAT DO SOME OF THE ETHICAL CHALLENGES OF BUILDING SHARED SPATIAL FUTURES LOOK LIKE IN PRACTICE?

Building for the private market has the advantages of having both the right economic incentives (a single bottom line) and the ease of inferring preferences from the evident self-interest of the players involved. But planners and urban designers build public spaces and infrastructures for diverse groups of people through democratic institutions using collectively generated revenues. On top of this, they are tasked with planning for future generations, which demands the deployment of sustainable designs.

These are innately ethical challenges because there are myriad and competing claims on these public things, places, and funds. Deciding their future requires debate, coordination, collective action, and, ultimately, trade-offs, including intergenerational ones. Compared to building for the private market, publicness implies the possibility of sharing public things with people who cannot pay full price for them. Not everyone is going to be happy with the resulting arrangements, and political representatives have a hard time surmising when the collective is satisfied—until they get voted out.

I worry that highly polarized societies refrain from and even renounce investing in public things. At our present juncture in the United States, there is a belief that public investments are wasteful, and everything could be better managed by the private sector, so we’re seeing public schools, publicly owned land, public administrative buildings, and natural resources being divvied up and sold off to the highest bidder. Privatization removes things from the public sphere and reduces the potential of democratic governance. As a result, these entities become more responsive to the demands of those with capital.

I really enjoyed teaching the Public and Private Development course this past term, which challenged students to think about the “proper” balance of public and private ownership, funding, and governance in urban development. The class discussed how private developers, municipal governments, and nonprofit organizations could work together in conflict-riven settings without ceding moral ground.

WHAT EXCITES YOU ABOUT WORKING WITH GSD ALUMNI?

The GSD has one of the most active alumni networks on campus. Some aspects of this network are instrumental, like helping one another find jobs, but it’s clear to me that the network is also sustained by friendships and deep personal connections to the school and university. Our alums are willing to drop everything and Zoom in for a guest lecture or return to campus for Comeback reunions. They meet up in the dead of winter at the Alumni Council’s Regional Gatherings around the world.

Our professional fields are being radically restructured right now, and the GSD alums working domestically are on the front lines of these changes. In the United States, they are witnessing a decline in federal funding for transportation infrastructure, the rolling back of environmental regulations, and a desire to replace the administrative state with AI. In their roles leading municipal planning agencies, as consultants, and as designers in architecture and engineering firms, they have a lot of important advice to give to our current students, who are understandably confused about the job market they will encounter when they graduate. One of my goals over the next few years is to connect our alums to our current student cohort to strategize about how to navigate this new environment. Thinking about the global (as opposed to domestic) job market may be an important pivot.

OUTSIDE OF YOUR ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL LIFE, WHAT HOBBIES AND ACTIVITIES HELP YOU RECHARGE?

Outside of work, you will find me slogging (slow jogging) around Fresh Pond. I like to cook and am happy to have found the Armenian greengrocers and bakeries along Mount Auburn Street in Watertown. I scroll Street Style photos. I read fiction and poetry and attend screenings at the Harvard Film Archive. Music (playing it, listening to it) has been a constant in my life, and the Boston area is home to some of my favorite college radio stations. My husband and I were both college radio DJs once upon a time—though our children couldn’t be less impressed!

WHAT ARE YOU READING RIGHT NOW, AND WHAT BOOK DO YOU RECOMMEND TO OTHERS?

Like most planners and designers, I’m a sucker for anything with the word “future” in the title, but Naomi Alderman’s The Future was one of the best books I read this year. Somehow this dystopian sci-fi novel about climate change and surveillance capitalism manages to be funny, thrilling, and insightful. It’s a takedown of Silicon Valley tech moguls who are deeply invested in shaping a future that serves their interests. I also liked this book because I’m currently writing a more academic version of it—looking at how real estate companies and asset managers are acquiring proptech start-ups, not only to anticipate but also to game future property markets.

You probably thought I was going to recommend The Power Broker!