Collaborative Design Engineering Studio II

The second-semester studio builds upon theoretical and technical concepts already introduced in the MDE program, emphasizing problem assessment, creative and critical thinking, observational and experimentation-based evaluation, and context-aware communication strategies essential for complex problem-solving activities. Within the scope of the 2D, 3D, and 4D MDE studio pedagogy, the fourth dimension, time, will feature strongly in project considerations. Students will be challenged to prioritize deeper reflection and holistic connections across the entire ecology of their design-engineering project (i.e. systems design, experiential design, futuring, and large-scale thermodynamics).

This year, student teams will develop a semester-long project on “Water as a System of Care” through one of three human-centric-scales: IN the body (i.e., medicine, nutrition, drinking, TOUCHING the body (i.e. fashion, beauty, recreation, thermal health), or AROUND the body ( i.e., infrastructure, transportation, construction). Student teams will develop product-based solutions leveraging an interdisciplinary approach that blends design thinking with insights from economics, sociology, technology, and public policy. Collaboration with experts across these fields, as well as with the communities that will be affected by these changes, will be vital in developing human-centric solutions that are truly desirable, feasible, and tangible.

This Studio is limited to first-year students enrolled in the Master in Design Engineering Program, a collaborative degree program associated with Harvard GSD and SEAS.

Landscape Architecture IV

The Near Future City

The fourth and final semester for the core Landscape Architecture sequence responds to our most pressing urban agenda in the years to come to transition into climatically just and resilient cities where no-one is left behind. As a Landscape Architect your role in this urban climatic transition is fundamental. Core IV provides you with the tools and skills to translate the important values and actions embedded in this process, into individual design proposals that are specific and concrete for the City of Boston.

In the Spring of 2024 Core IV joins current efforts from the federal, municipal, and civil society to accomplish this needed task. Among others: President Biden´s administration realignment with the Paris Agreement followed by his American Jobs Plan[1] and the Roadmap for Nature-Based Solutions[2] at the COP 27; the commitment to swift from fossil fuels at COP 28; Mayor Michelle Wu’s Boston Green New Deal & Just Recovery [3] synthesizing many of the Boston Climate Action [4] initiatives toward climate resilience and decarbonization; or EPA5 and the Mystic River Watershed Association to reduce pollution. The semester opens with an immersive pre-term symposium to learn first-hand from state, city officials, and NGOs on their multiple Boston plans, initiatives, and policies while experts share important precedents and critically assess the encounters. As an academic exercise, we will have the freedom to move beyond the “status quo” of present possibilities, to more desirable outcomes toward climatic resilience in the Near Future. While enhancing your imagination in the creative process of design, this might be precisely where our collaboration becomes more nurturing and catalyzing.

After the opening, the semester is structured around three ACTIONS: 01. analyzing; 02. spatializing; 03. projecting. Each ACTION combines expert lectures, readings, skill building workshops, and exercises that built sequentially and iteratively upon each other during the semester. In closing, students assembled their work for a Near Future Charlestown Presentation to continue the engaging conversation that was started at the opening symposium.

Fourth Semester Architecture Core: RELATE

The fourth and final semester of the core sequence, this architecture studio tackles the complexity of the urban condition through the design of housing. From individual to collective, from spatial to infrastructural, from units to systems, housing not only confronts the multiple scales of design but also exposes the values and ideals of its society. The semester will be an opportunity to imagine the possible futures of the city, recognizing the role of architecture at the intersection of the many interdependent as well as contradictory forces at play, and the negotiations that must necessarily take place.

The semester will be organized in two overlapping phases. The first weeks will be an intense research and analysis phase through which the students will develop not only an understanding of historical precedents but also begin to formulate their narrative on urban living – a hypothesis that they will use to launch their design for the rest of the semester. While this hypothesis will be constantly revisited and revised, it will serve as a first speculative act.

The second phase of the semester will be devoted to the elaboration of an urban project with a focus on housing and will have as its objective the understanding of design as a series of relativities: between building and the city, between collective and individual, between civic and domestic. The architectural project is fundamentally optimistic. It goes beyond problem solving to imagining a better future. In no other typology is this more true than with collective housing which defines the core of how we live and function together as a society.

Pedagogically, working in groups and pairs will be a component of the semester, demanding dialogue, understanding, and negotiation of different points of view.

Please refer to the course syllabus for classroom information for the Wednesday afternoon Core Studio Colloquium.

Second Semester Core Urban Planning Studio

The second semester core planning studio expands the topics and methodologies studied in the first semester core studio, GSD 1121, aiming to prepare students for the mix of analytical and creative problem-solving needed to be an effective planner. In this studio, students work on a real project in a real place (with a real client) that allows them to interact with the public; define a vision; collect, analyze, and represent data that supports that vision; develop a proposal that reflects public input; and present work in a sophisticated way that is relevant, legible, and useful to those who are not planners. By the end of the studio students will be familiar with a number of dimensions of community engagement, data analysis, plan making, and implementation.

Landscape Architecture II

The studio will explore how we might reimagine cemetery landscapes of the future in response to the challenges of the climate crisis, and the clear and present issues of social inequality. These issues are extensively shifting the ways we live, and, at the very least, are the uninvited corollary through which we might imagine new expressions of the cemetery.

As sites of remembrance, cemeteries may be considered as ‘places where memory crystalises and secretes itself as part of an ongoing construction of history’ (Pierre Nora 1989), whilst simultaneously acting as ‘settings in which memory is a real part of everyday experience’ (Michael Rothberg 2010). They are spaces that are socially produced and made productive in social practice (Lefebvre 1974), whilst also being highly logistical practical settings created in the absent presence of the body (Ken Warpole).

Just as death is a necessary part of life, cemeteries are sites of contrast, yet it is perhaps through the very preservation of this tension of contradiction that they exist as some of the most enduring landscapes across cultures around the world.

Often perceived as a space ‘apart’ from the city as a consequence of their physical traits and phenomenal characteristics, cemeteries none the less play significant roles within the life of the metropolis as biodiversity hotspots offering ecosystem services in the form of thermal regulation, stormwater management, and carbon absorption. They provide significant social functions such as spaces for people to seek sanctuary, reflection and play, and healthy spaces for individuals to contemplate in the context of a natural landscape.

Cemeteries, capable and perhaps charged to carry multiple meanings, are paradoxical spaces described by Foucault (1967) as ‘heterotopias’, a no place that, nonetheless, is. The studio will be exploring what the urban and social significance of the cemetery of the future could be, and ask what are the forms and cultural expressions the urban cemetery might project? How might the articulation of the material and physical space reinterpret the temporal experience of the cemetery, and how might the increasingly rich cultural diversity of a progressive society be celebrated through ritual and mediated through disparate processes of burial and internment? How might the cemetery critique and address the extensive environmental and social issues that are before us by proposing alternative organisational patterns and expression, a place that celebrates diverse beliefs and rituals, and a space as an important contribution to the city’s natural systems?

Second Semester Architecture Core: SITUATE

The overarching pedagogical agenda for second semester is to expand upon the design methodologies developed in the first semester such that students acquire an understanding of the interwoven relationship between form, space, structure, and materiality. This semester extends the subject matter to include the fundamental parameters of site and program, considered foundational to the discipline of architecture. Through the design problems, students will also engage in multiple modes of analytical processes that inform and inspire the study of mass, proportion, and tactility.

Prerequisites: GSD 1101

Resolution Grounds: Designing with the Fragmented Survey

Paris Bezanis (MArch I ’25)

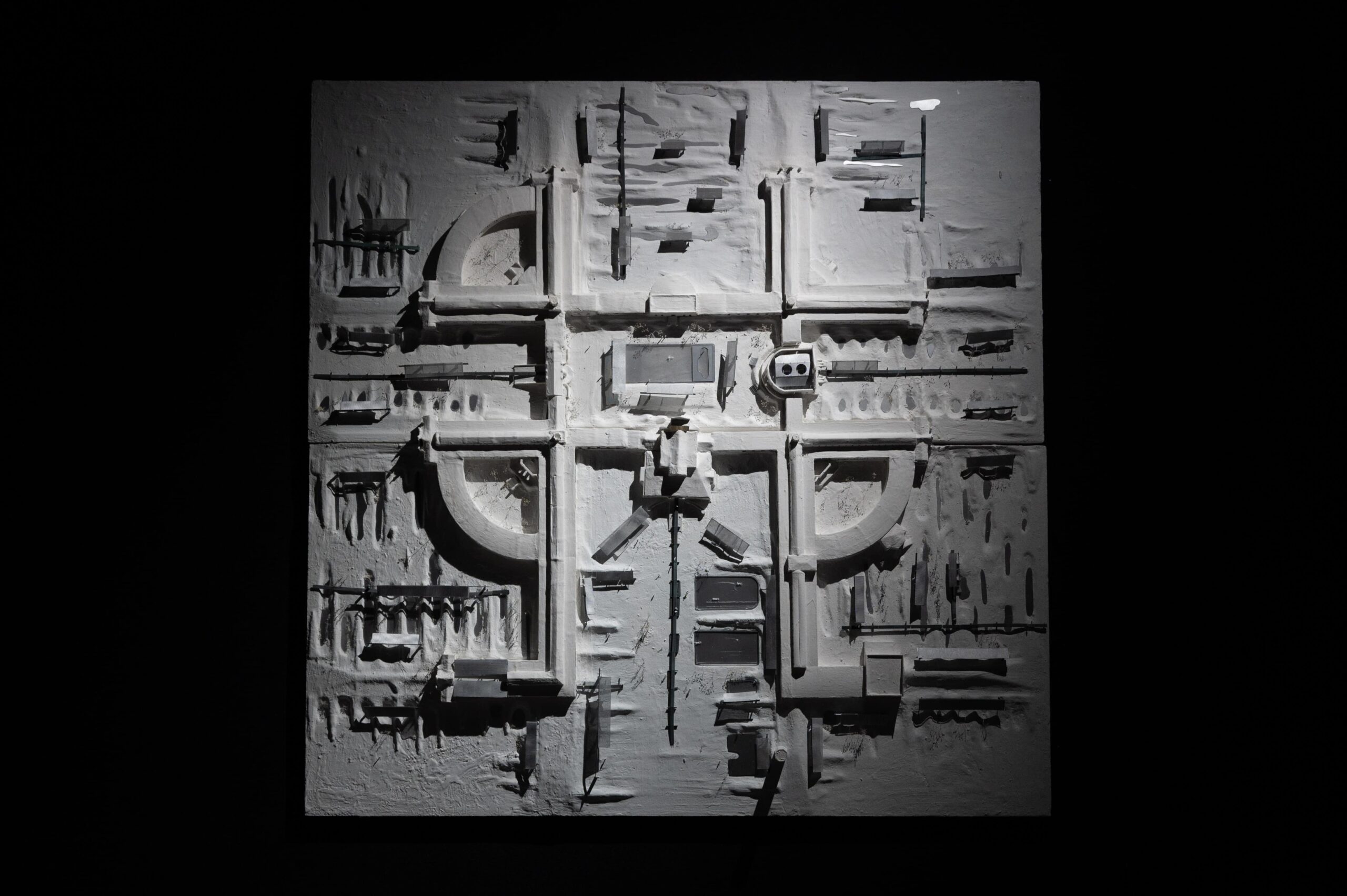

Resolution Grounds: Designing with the Fragmented Survey repositions the architectural survey as a site of epistemic and political contestation, challenging the premise that more data yields better design. At the Kuyalnik Estuary in southern Ukraine—a landscape shaped by ecological collapse, centuries of colonial therapeutic infrastructures, and wartime inaccessibility—the disciplinary pursuit of total visual capture is not only infeasible but ethically compromised. In its place, the thesis advances the fragmented survey: a methodology that constructs spatial records from open source but incomplete, low-resolution, and often extralegal visual material. Scraped drone footage, social media images, and archival fragments are not treated as raw inputs, but as situated digital artifacts, reconstructed through AI-assisted workflows that infer missing metadata and spatial relationships. Screenshots from embedded Google Maps flyovers are processed using monocular depth estimation tools like Marigold and Stable Diffusion, then passed through photogrammetry platforms such as RealityCapture or MeshRoom. Photogrammetry is operative here because it enables the translation of heterogeneous, often degraded visual material into spatial data—producing point clouds and meshes that can be acted on architecturally. The resulting outputs range from broken, sparse point clouds to partial meshes with high degrees of inference—surfaces warped by algorithmic guesswork and visual noise. These are supplemented with inpainting, deblurring, and neural alignment techniques, and further anchored by high-resolution Polycam scans captured on-site by local collaborators. The result is not a seamless model of a digital twin, but a digital sibling: an unstable, multiscalar, and composite reconstruction that foregrounds the technical and political conditions of its own assembly.

This composite and fragmented survey becomes a design instrument calibrated to its own inconsistencies. Each resolution informs a different scale of architectural intervention: coarse, inferred terrains underpin landscape-scale berms and sedimentary commons; intermediate scans guide the reuse of precast concrete elements from nearby Soviet housing stock; high-resolution fragments support detailed tectonic insertions within sanatorium ruins. By designing through interference rather than resolving it, the project reframes digital surveying not as a pursuit of mastery, but as a situated, ethical design practice. Here, resolution is not merely a technical attribute but a methodological stance—foregrounding approximation, scarcity, and collaboration as design prompts. In doing so, the project proposes a new role for computation in architecture: not as a tool for seamless visualization or predictive modeling, but as a critical mapping practice attuned to the politics of fragmented data, uneven visibility, and constrained access—where what can be

rendered is shaped by platform infrastructures, geopolitical opacity, and the contingencies of image circulation.

CREDITS

DDP Credits and Attributions

Paris Bezanis

Spring 2025

Credits and attributions are listed below for any work shown in the thesis project that is not exclusively my own.

Citations

- Bingxin Ke, Kevin Qu, Tianfu Wang, Nando Metzger, Shengyu Huang, Bo Li, Anton Obukhov, and Konrad Schindler. “Marigold: Affordable Adaptation of Diffusion-Based Image Generators for Image Analysis.” arXiv, May 14, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09358 . Code repository. PRS_ETH. https://github.com/prs-eth/marigold .

- Riku Murai, Eric Dexheimer, and Andrew J. Davison. “MASt3R-SLAM: Real-Time Dense SLAM with 3D Reconstruction Priors.” arXiv, submitted December 16, 2024; revised June 2, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.12392 . Code repository. Imperial College London. https://github.com/rmurai0610/MASt3R-SLAM .

- Carousel image 21, bottom. Pierre-Yves Brunaud, photograph of paysarchitectures project in Geneva, 2017. Used as the base for a digital collage by the author.

Labor

Plastering model: Olivia Champ, Maria Ferrari, Hannah Kim

Planting and boardwalk assembly: Griffin Snyder, Emily Hayes, Aneesh Devi, Becca Schalip

Interiors Visualization Assistance: Denis Sola

Form Follows Forest

Kei Takanami (MArch I ’25)

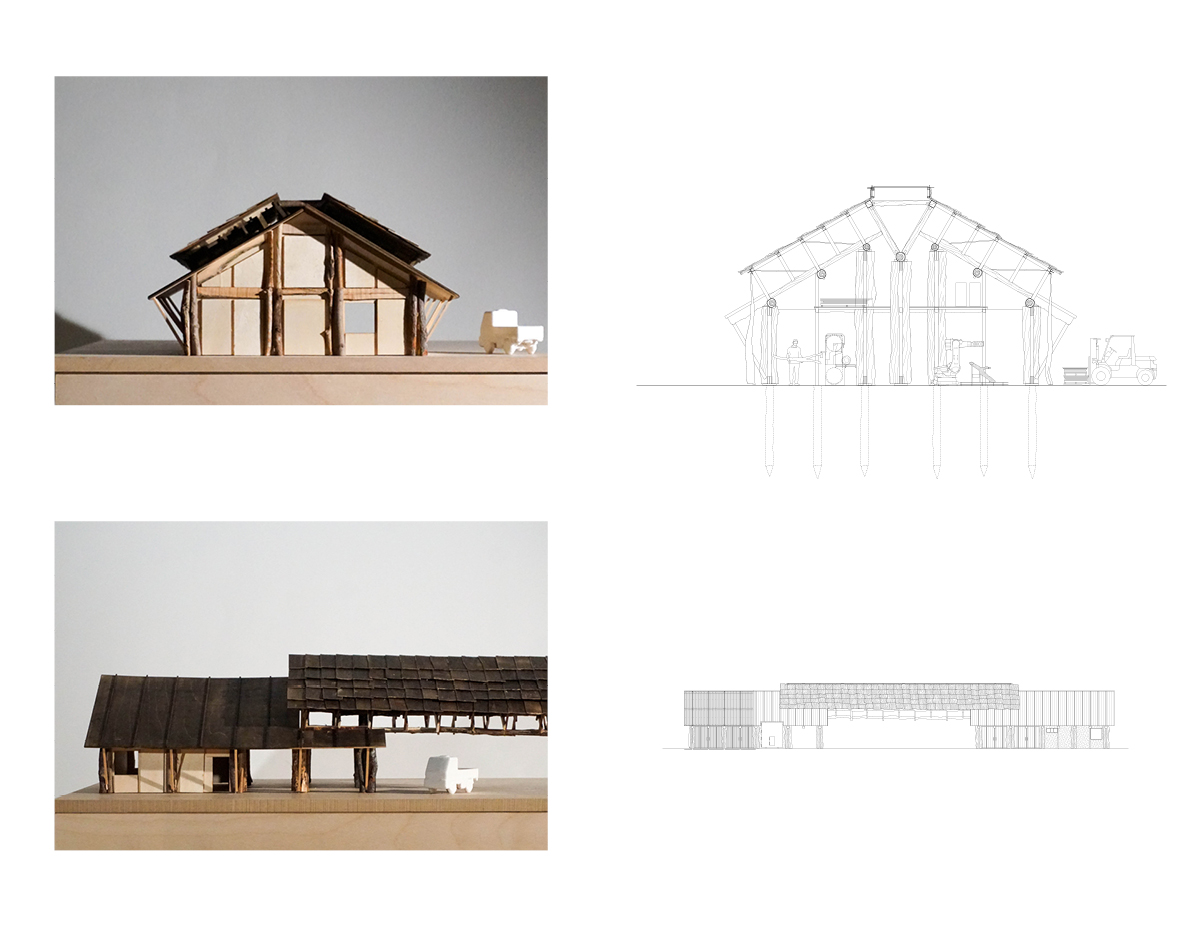

Form Follows Forest explores architecture’s potential to re-engage with the timber industry—from upstream extraction and processing to assembly and construction. Rather than treating wood as a passive commodity, the thesis investigates ways of integrating small-diameter, irregular, and underutilized timber into building systems—aligning architectural assemblies with the conditions of the living forest.

Japan’s forests were once diverse in conifers and broadleaf species, managed through ecological rhythms and small-scale labor. Yet, these landscapes have since been reshaped by postwar industrialization, shifting energy demands, and the globalization of timber markets. Today, monoculture planted forests of aging cedar and cypress dominate the landscape, leaving forests underutilized and ecologically fragile. Meanwhile, contemporary architecture has grown increasingly disconnected from its material origins, favoring standardized construction that disregards the irregularity and potential of local wood.

The thesis adopts a design method based on larger tolerance and clearance zones assigning maximum zones of interference and parameter ranges to irregular members. Enclosures and auxiliary elements work around these zones, using techniques of infill and scaffold, while clearing structural walls from interference proximities.

Two speculative buildings, in Hanno and Shinkiba, demonstrate this approach at different points in the timber material flow. By reengaging thinned, knotted, and twisted wood, the project challenges conventional notions of material efficiency, standardization, and tolerance. Together, these proposals demonstrate how architecture can respond to the evolving conditions of the forest, linking material source and built form.

The Only Way Out is Through: Architecture, Building and Our Entangled Present in Gary, Indiana

Connor Daniel Gravelle (MArch II ’25)

Architecture frequently operates in abstraction. From drawings to models, our discipline functions mostly through intermediating media. Buildings, however, are innately material. Buildings bind architecture to the world, entangling it in issues of material, labor, and ecology with which it has historically been ill-equipped to contend.

This thesis explores Gary, Indiana—a place defined by the afterlife of such occlusions. Responsible for the steel that made not only Chicago but the nation, Gary was created in the image of industrial modernity, but the relations that sustained its prosperity no longer hold water. Changes in the American economy and the stagnation of the domestic steel industry leave Gary in a state of precarity familiar throughout the Rust Belt.

This project imagines a (not entirely unfathomable) bankruptcy of US Steel in the near future, unfurling the social and ecological processes that could be undertaken to remediate its sprawling facility in Gary. The thesis unfolds through a series of studies into the histories, construction techniques, and material qualities enmeshing architecture and steel, envisioning a reorganization of the equipment and skilled labor left in the wake of US Steel’s insolvency to construct, operate, and eventually repurpose a facility for dismantling, recasting, and reusing Gary’s centerpiece factory in an act of civic and environmental remediation. US Steel’s plant, after all, is itself made of steel, and steel is infinitely recyclable.

If architecture is as much recasting of iron ore into steel as it is the recasting of relations between people and land, what agency do buildings have to rewire how we relate to our entangled present?

Laptis

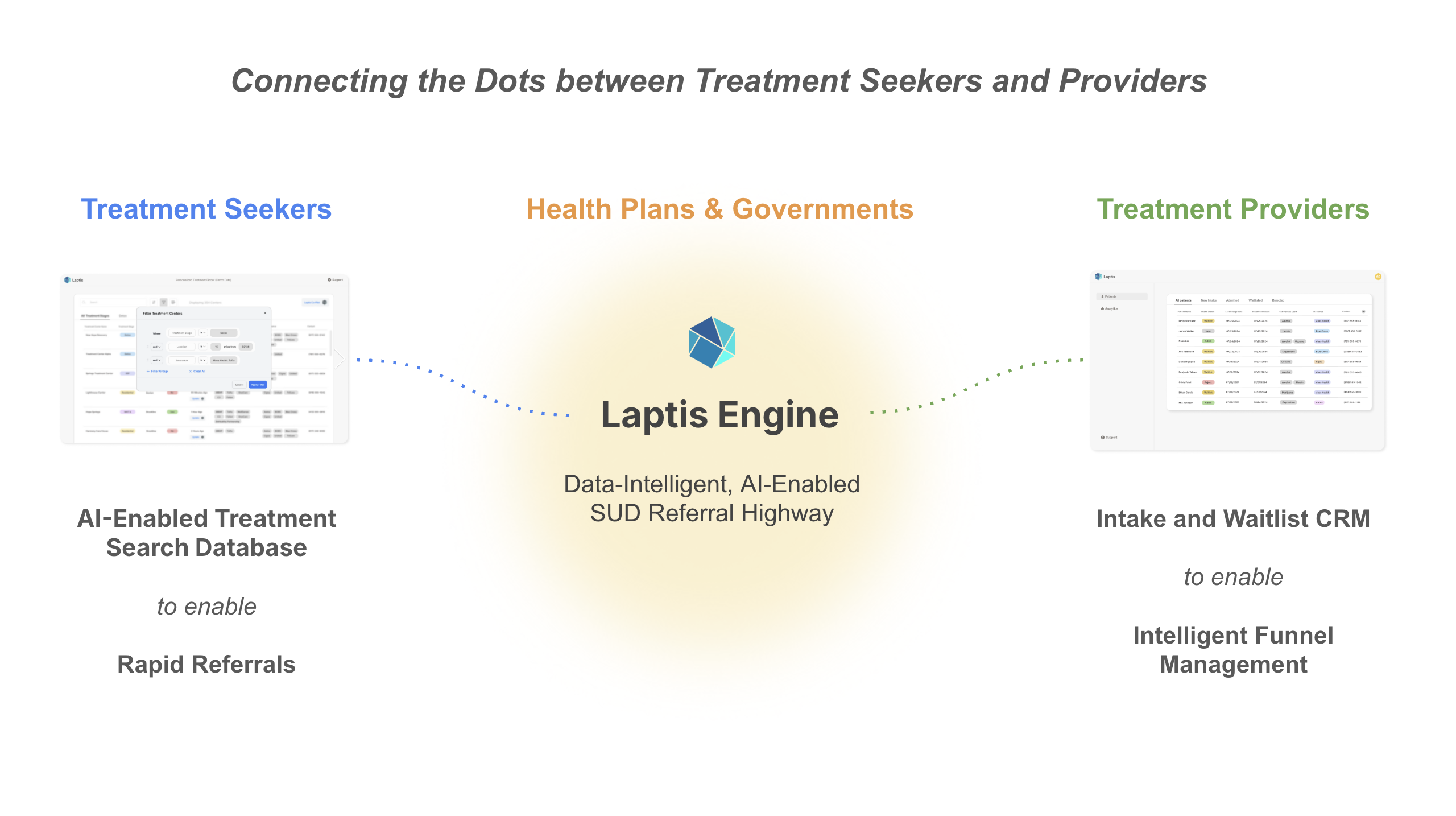

Kevin Hu (MDE ’25)

Today, over 47 million Americans struggle with substance use disorder, and hundreds die from overdose each day. To find care, treatment seekers must wade through archaic systems that are fragmented, opaque, and time consuming to navigate. This lack of access and coordination drives hundreds of billions in unnecessary costs and means less than 10 percent of people with addiction actually receive care.

At Laptis, our mission is to streamline access to trusted substance use treatment. We are building an AI-enabled, data-intelligent referral highway to connect the dots between those looking for addiction treatment and those who can provide it. Our technology bridges patients, providers, and health systems—ensuring that individuals in crisis are met with clarity, speed, and trusted care pathways. Laptis is now live in multiple hospitals and treatment centers across Massachusetts, having connected over 300 people to care.