American Brick and the Difficult Whole

Yuming Feng (MArch II ’21)

Nothing engages more in the dialogue of “rationalism in material” than brick. On the one hand, the structural nature of brick was rendered meaningless by the modern need for large and flexible spaces; on the other hand, the critique of the new construction systems as cold and indifferent makes the cultural aspects of brick more important than ever.

As a multicultural center at Rice University, this project tries to establish a new ground for brick architecture in which brick fulfills both its structural value and cultural purpose. The facade is a brick architecture that inherits the material tradition of the campus; the interior, which makes use of timber, is an architecture with various scales of programs. The coexistence of the timber interior and the brick exterior immediately breaks the continuity between the content and context.

To address this discontinuity, the brick facade was designed to speak to the campus with order, symmetry, and proportion while responding to the interior with “material transfer,” which gives it the characters of timber. Moreover, the facade uses “diaphragm bonding” to perform structurally with timber. In this way, the brick not only “decorates the shed” but also participates actively in other fronts of the architecture. By reiterating the theme of material transfer, the four columns at the center are the architectural summary of the project. The details that distinguish the four columns focus on how they meet the ground and the roof, and clearly express the construction logics of the original and transferred materials.

Visit the 2021 Virtual Commencement Exhibition to see more from this and other prize-winning projects.

Running the Course: Unifying Franklin Park One Step at a Time

Lucy Humphreys (MLA ’22)

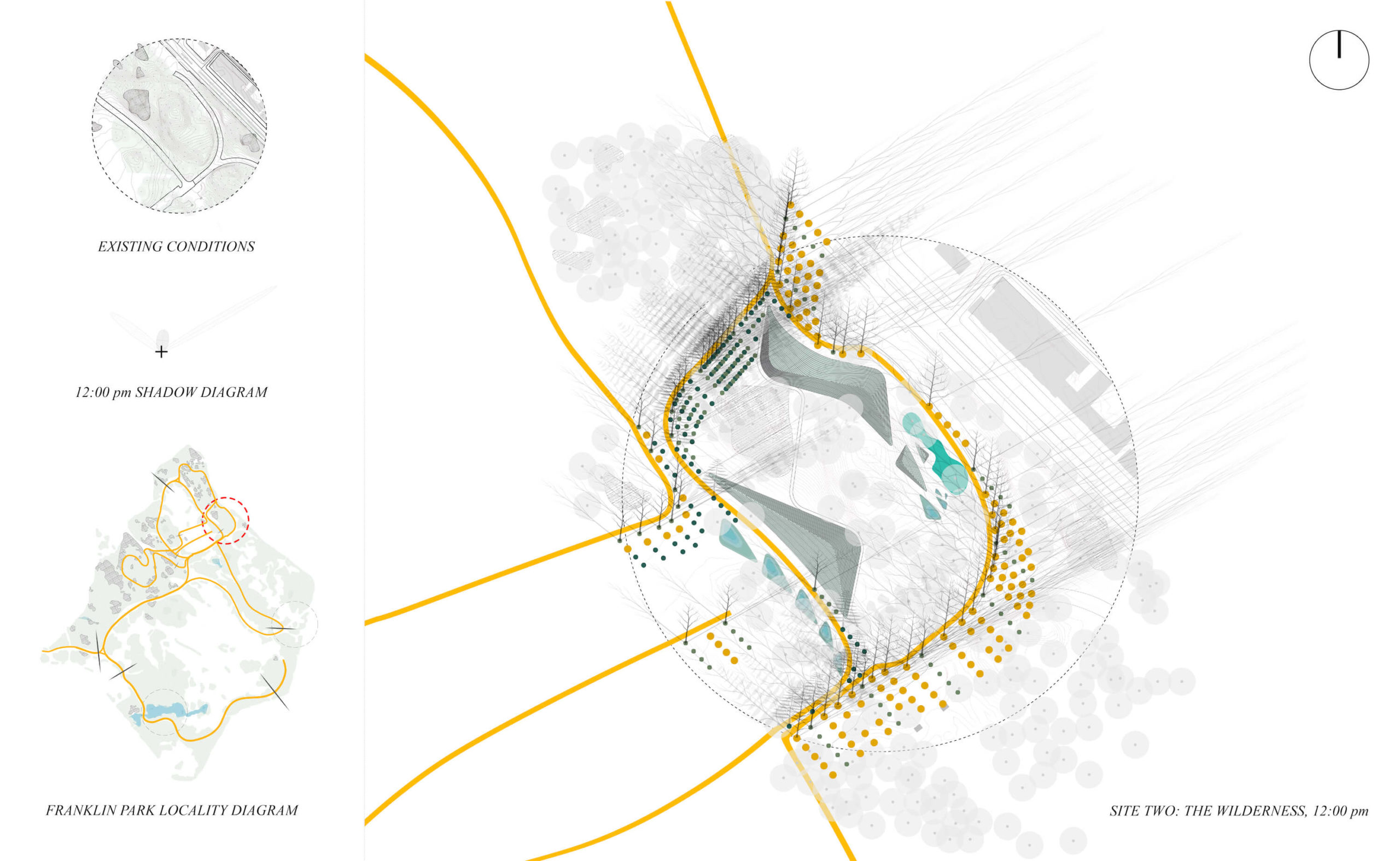

Franklin Park, the Eastern-most park of Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace, exists at the intersection of Roxbury, Dorchester, Forest Hills, and Jamaica Plain, four culturally and economically diverse neighborhoods. Although the 527-acre park provides significant recreative opportunities for nearby residents, it is not a unified park. For example, one cannot move comfortably from Refectory Hill to the Playstead without hitting a paywall or circumventing the golf course. Franklin Park therefore presents a tremendous opportunity for unification.

The experience of a large park can be a valuable one. Franklin Park offers an immersive interiority into nature that would otherwise be inaccessible for many residents surrounding the park. Franklin Park offers a common outdoor experience for neighboring residents, fostering a sense of community in the greater Boston area. Additionally, I believe there is value in revitalizing and investing in existing landscapes and communities. Elements like the cross-country course, the zoo, and the playgrounds offer key programming for the surrounding neighborhoods and Boston at large.

My goal in this project is to revitalize Franklin Park by augmenting the unique and world-renowned cross-country course that brings athletes from all over the world and unifies the park for a few days of the year. The path of the course is the catalyst for a new range and scale of social spaces, vegetation revitalizing strategies, and land forming interventions designed to stitch the park together. It will create a new rhythm for the park.

The aspiration of this project is to evoke further enthusiasm, excitement, and interest in Franklin Park as a community space for the surrounding neighborhoods and the greater Boston area. Race Day, and the landscape network it supports, renders the park truly public.

POV

Ali Sherif (MArch I ’23)

The sports complex splits the program into two types: collective and individual, spectated and personal. This manifests itself physically in two ways: the box and the worm. The boxes house spectated sports, basketball, handball, and roller hockey, and are designed as simple, inconspicuous sheds. Their white mesh exteriors and white-painted structure reduces them to their simplest of form and color. To minimize the building’s footprint, the boxes are sized to just the courts and pivot at a hinge point, creating public spaces on either side.

All other program and circulation cores exist in the worm. The worm is a bright red tube that sculpturally materializes, and stands out, amidst the brick fabric of Boston’s North End. The worm wraps itself around the boxes in one continuous motion, engulfing the white structures, breaking through the mesh barrier when it needs to accommodate for larger activities. It morphs itself into spectator seating, gyms, cafes, elevator shafts, stairs, yoga studios, among other things, preserving the appearance of thinness at all times.

While the boxes are dimensioned to the scale of the courts, the worm is dimensioned to the scale of the person. The thinness of the worm creates an intimate spatial experience, affording the individual a sense of ownership over the space being used at a certain moment in time. In addition, the sectional scalar disconnect between the box and the worm provides the user a typically non-existent layer of discretion while exercising. The individual is maintained at the position of the spectator at all times, while the collective is preserved as the spectacle.

Highlands’ Harvest

Alysoun Wright (MUP/MLA I AP ’21)

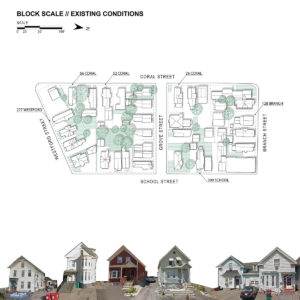

The Lower Highlands neighborhood of Lowell, MA consists predominately of residential blocks. Additionally, 30% of the neighborhood’s 74% impermeable surfaces are categorized as driveways and lots. Parking demand and considerations of maintenance in a high renter context often preference impermeable surfaces, thereby contributing to surface water runoff, water contamination, and urban heat island effect. In response, the Highlands’ Harvest pilot program seeks to increase permeable surface within the Lower Highlands Neighborhood by leveraging existing interests in gardening and food production and creatively making use of residual space within the dense urban fabric.

The Highlands’ Harvest Program is an optional program that is targeted towards residential blocks with less than 40% permeable area. As part of the program, homeowners self-identify impermeable portions of their parcel that are underutilized, or could perhaps function similarly with a more permeable surface covering. These spaces are then enrolled in a lease agreement with Highlands’ Harvest which pays a rental fee to the homeowner. The use and management of this space can then operate in several different scenarios, in which either a homeowner, renter, or Highlands Harvester would have the option to manage the space.

Full implementation of the Highlands’ Harvest program would result in the distribution of herb gardens, flower patches, and urban farming across residential blocks within the Lower Highlands. The harvest of these micro-sites would then be aggregated and redistributed as an ongoing CSA to block participants.

The objective of Highlands’ Harvest is to build upon the neighborhood’s existing strengths in order to move towards and incentivize the creation of a more permeable urban fabric. The hope is to demonstrate that such shifts can be productive, collaborative, and incremental. Furthermore, it is envisioned that through this process both owners and renters alike will feel greater connection to their community and urban fabric.

Meeting House: Using the Window as a Generator of Interstitial Space

Sonya Falkovskaia (MArch I ’23)

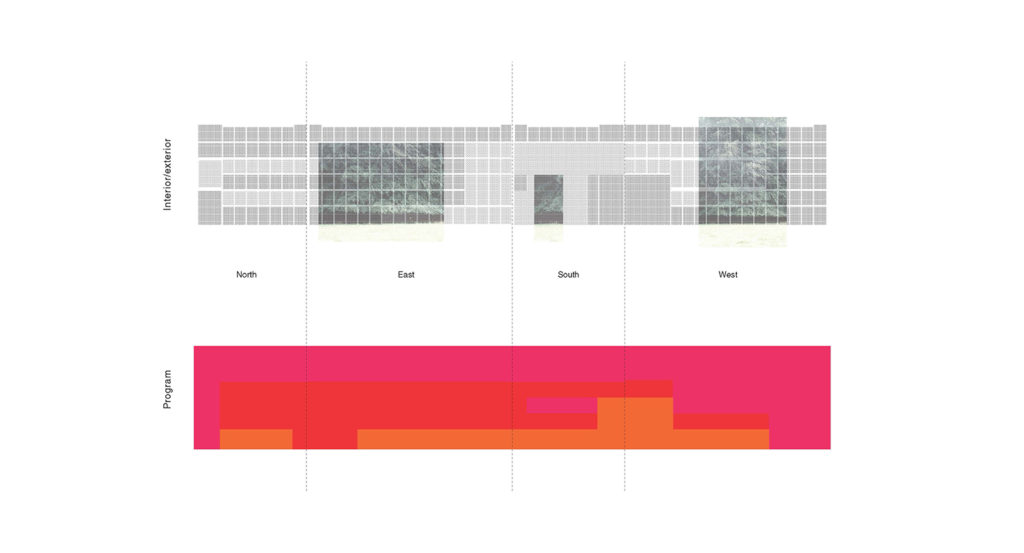

“Meeting House: Using the Window as a Generator of Interstitial Space” explores how a changing depth of facade can act as a mediator of varied interior environments. The window is our primary connection to the outside world when existing within buildings. This project experiments with what the window can come to represent and how it changes our engagement between internal and external space.

Much like the layers of a window, there is interstitial space that contributes to how we perceive these two fundamental elements. This building aims to take the principle of layers within a window and apply them to the building, turning the whole facade into one cohesive window mechanism.

The project proposes a clubhouse for the Harvard campus, consisting of three houses: a community house, a guest house, and a graduate house. The three houses are intertwined to produce one place where each of the three groups across Harvard’s campus can connect.

Within each house, there are three scales of room. The smallest module of the room is used to build the rest of the building. Each scale contains a fragment of the concept that gets compounded when reading the building as a whole. The building is created by an enveloping thick facade that wraps around to create a void within. The facade is folded both in plan and section. By using this folded surface, light and air are maximized.

Cutting the Tall Grass

Sharon Cornelissen (Postdoctoral Fellow)

Sharon Cornelissen lived and became a homeowner as an ethnographic researcher in Brightmoor, Detroit for three years (2015-2018)—one of the United States’ most depopulated, poor, Black neighborhoods. Since 1970 Brightmoor had lost over half of its residents, while it turned from all-white to 83% Black. Wildflowers flourished here amidst hundreds of emptied homes. Residents saw wild deer as often as they heard gunshots. And in 2006, a surprising new phenomenon began: white middle-class newcomers started to move in, who called themselves “urban farmers” and planted gardens and farms on vacated lots.

Drawing on over 1500 pages of ethnographic fieldnotes and 70 in-depth interviews, Sharon is writing the book Cutting the Tall Grass, in which she sets out to answer two core questions: One, how did extreme decline and depopulation affect the lives of Black and white longtimers? And two, why did middle-class white newcomers move to this devastated place? To answer these questions, she will show how decades of neighborhood decline shaped racialized losses and opportunities, hardship and privilege, and trauma and coping, as devastated Brightmoor faced early gentrification.

Her book revolves around four key chapters. First, she will explain how and why so many longtime Detroiters lost their homes a decade after the subprime mortgage crisis decimated Black communities across the United States. As many Brightmoor homes had become worth less than second-hand cars, and with little to no credit available, many residents became forced to treat their most prized possession as a disposable good: something they were using up. Many longtimers lost their homes to tax foreclosures, often after years of hardship, lost jobs, burnt-out furnaces, leaking roofs, and grief and worries.

Second and by contrast, she will show how white newcomers turned this housing distress into exclusive opportunities. She describes the moral code newcomers used to navigate buying in a market haunted by loss and shows how newcomers turned lost homes into prized Detroit urban farmhouses. She argues that their relative privilege was instrumental to help them profit from one of the United States’ most depressed property markets. Longtimers’ tragedies became white newcomers’ opportunities.

Another chapter of the book examines how longtimers and white newcomers differently related to the return of greenery in depopulated Brightmoor. Some vacated blocks more resembled rolling fields than anything else. Most longtime residents hoped that Brightmoor would regain urban density. They decried wildflowers and tall grasses as weeds. Many vigorously mowed vacant lots. White newcomers, by contrast, supported wildflower fields and housing demolition without rebuilding. They viewed vacated blocks as country-like and kept chickens, goats, and honeybees. What Sharon calls “traumas of decline” shaped whether residents foregrounded depopulated nature as blight or bucolic, as urban absences left in the wake of depopulation and disinvestments, or as new rural presences, signaling Brightmoor’s incipient ruralization. Acting on and with nature, residents worked through ideals of decency and respectability, through feelings of control and anxieties about violence, and through conflicting dreams of urbanism or post-urbanism.

Finally, she discusses how white newcomers’ and longtimers’ different relationships to the neighborhood’s past shaped their public lives. Traumas of neighborhood decline and historical violence lingered for longtimers on street corners, in fields of tall grass, and in unsuspecting moments. By contrast, for white newcomers, historical violence was only a fact of oral history, rather than lived biography. Their strategies for navigating public life came from positions of white privilege, and their aspirations for Brightmoor were often based on their experiences growing up in white, middle-class neighborhoods. As a result, white newcomers often acted in ways that other residents considered unsafe, such as by organizing a weekly farmers’ market across from a notorious open-air drug market.

Overall, this project makes significant contributions towards understanding the relationships between urban decline, gentrification, and racial inequality. It also calls for scholars to incorporate an understanding of traumas of decline into their analyses of the detrimental impacts of neighborhood disadvantage. The book offers a thorough analysis of such trauma, its relationship to racialized dispossession, to coping, and dreams of redemptive urbanism. Conversely, it unpacks the distinct orientations, privileges, and historical conditions of white gentrifiers, by closely examining this unusual case of early gentrification.

Independent Thesis for the Degree Master in Design Studies

(Previously "Open Projects”) Prerequisites: Filing of signed "Declaration of Advisor" form with MDes office, and approval signature of the program director. A student who selects this independent thesis for the degree MDes pursues independent research of relevance to the selected course of study within the MDes program, under the direction of a Design School faculty member.

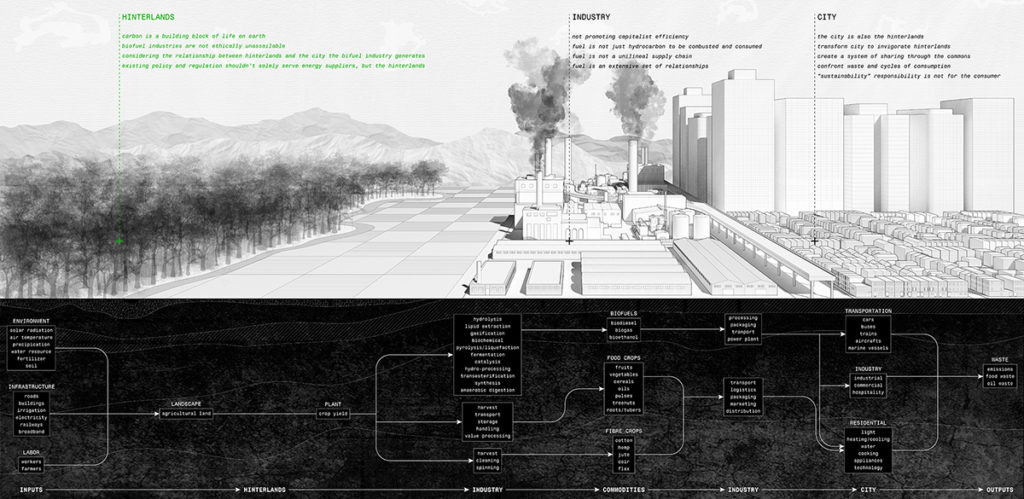

Transmission Right of Way

Fabiana Casale (MLA I AP ’22), Yvonne Fang (MLA I ’21), and Maria Ulloa (MLA I AP ’21)

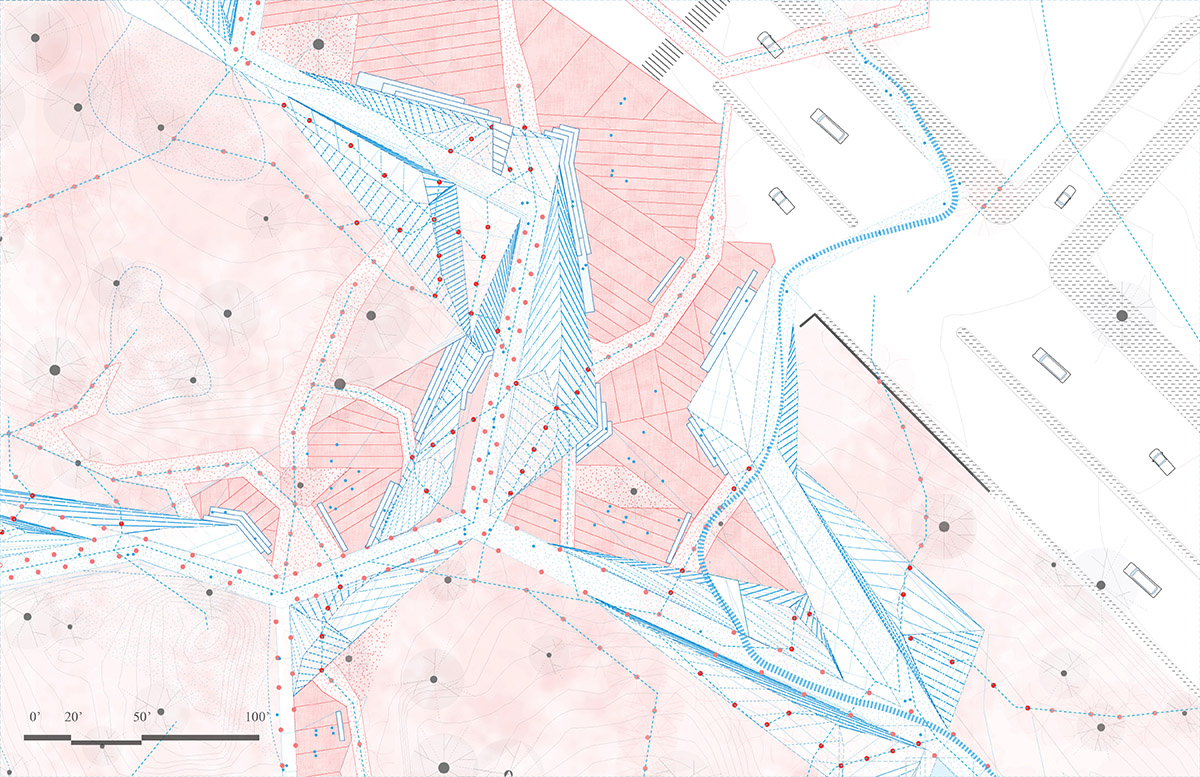

Currently, energy production and consumption within the city is depleting the hinterlands. Despite attempts to adapt “sustainable” modes of energy, existing urban lifestyles continue to accelerate land degradation through resource extraction in the hinterlands. We acknowledge that our consumptive habits are shaped and exacerbated by forms of living in the city. As such, innovative urban spatial solutions are necessary for changing the way we dwell.

Situated in South Boston, “Transmission Right of Way” establishes a waste-to-resource conversion network that is facilitated by the ground and living systems. Our redefinition of transmission right of way as an ecological easement network first emerged through synthesizing hinterland reform policy and electric grid guidelines. This project establishes a new commons through an intra-urban network of collective land ownership that gives residents the agency to choose their level of investment.

This new transmission right of way generates public power and resources, meaning that we are neither beholden to the power supplier monopoly nor are we profit-driven. Along with our design proposal, the project stipulates that residential and communal land-uses must make way for living energy infrastructure that ensures the community’s reliable resource and power supply as well as transmission.

In our speculation of the post-carbon city, we cast urban form as a mutualistic system driven by expanded notions of spatial caring. This care comes from close encounters with land and ecological processes, altered relationships to consumption, and collective labor that engenders a living commons. This expanded care enables a new way of living that renounces energy as unilineal consumption and instead embraces the notion of energy in which we become accountable for all direct and indirect labor, costs, and sacrifices that support our existence. All in all, “Transmission Right of Way” is founded upon frank accountability, tenacious democracy, sincere institutional support, and above all, conscious love and care for absolutely everything that enables us to live aspirationally.

Live/Work/Rent

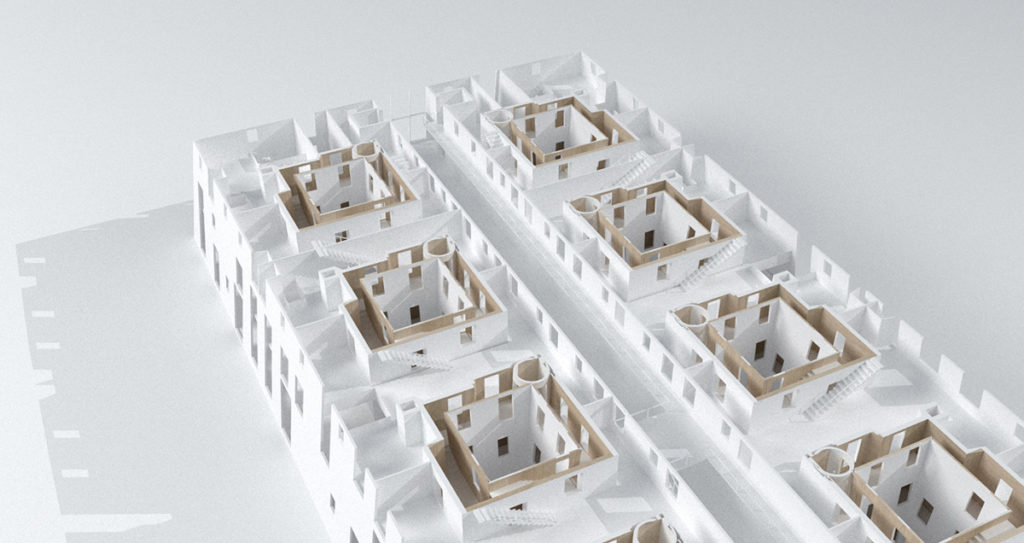

Tyler Rodgers (MArch I ’22) and Tracy Tang (MArch I ’22)

This project addresses the near future of collective housing for gig economy workers through the lens of a heightened housing shortage and the prevalence of self-employment in 2050. The proposal adapts the model of live/work cooperative housing to incorporate nested accessory dwelling units. The design enables residents to rent out part of their unit, challenging the normative conditions of residential spaces by allowing personal and industrial zones to overlap. We would like to propose a new condition of integrating remote gig working with a relatively stable lifestyle. We speculate that, in 2050, a group of gig workers would form a housing cooperative with a sustainable architectural environment for their 24-hour activities, including spaces for working, cottage-industry activities, small-scale production, and units that could be frequently rented out.

The form of the industrial deep plan is particularly appropriate for our site, which contains a mix of brick industrial and residential building types in close proximity. In addressing the condition of the site, we sought to combine signifiers of these two building types.

Based on precedent studies of the IBEB Cooperative Housing Project in Berlin and the Lacaton and Vassal Grand Park transformation, we established an initial critical area of focus on how to create a housing project that utilizes a deep plan, with integrated lightwells and community spaces for residents. These strategies of integrated light wells, community workspaces, and expanded interior streets, continued throughout the project.

Our second critical area of focus relates to the medium scale of our project: embedding a nested unit so the gig worker residents of our housing project can rent out part of their space and generate extra income. We began to study creating a thickened wall space within our project, where a nested accessory dwelling unit could exist. Nested towers of accessory dwelling units are situated between the primary units, ringing the lightwells of the deep plan. These nested towers form an additional community space at the medium scale of the project, and function as open spaces that provide light to the primary units ringed around them in the plan. The towers distinguish themselves from the primary apartments through a different interior materiality. While most of the building is conceived to be painted concrete, shown in white in this image, the towers inhabit a warm, wooden interior that is more intimate.

On the first floor, this variety of duplex units is arranged at the sides of the building touching the tower, so that each unit has access to a nested accessory unit. The first floor, as previously mentioned, has two conditions, a closed condition that separated communal workspaces, and an open market condition that connects these spaces into a continuous gathering hall. On the second and third floors, units are accessed from a large central communal street, and there are shared community spaces on the roof.

Within the project, there is a global relationship between the light well that brings light into the deep plan, the cozy nested accessory space, and the more spacious primary unit space.

Franklin Park’s Edge

Sophie Mattinson (MLA I ’22)

In “Franklin Park’s Edge,” the perimeter opens to its surrounding neighborhoods by relaxing the current topography for accessible pathways connecting the city’s street level to the park. Cues indicating entry into Franklin Park can be read from the ground: curb cuts, material transitions, pavers, and paint markings. Before crossing Sever Street and heading towards the park in its current condition, thickets of trees and boulders enclosed by stone walls obscure the interior’s view. Occasionally visitors are welcomed by signage and crosswalks located as frequently as each residential block, but those traveling from the quieter corners must hug the stone wall along narrow sidewalks and fast-moving avenues until they reach an entrance.