Geaugraphy

‘Neoliberalism’ has given globalization a bad name. But the ‘age’ after World War II has also produced ‘détente’ – ironic word – the disappearance of ‘blocks’ and triggered the elimination of many obstacles to exchange the massive facilitation of all forms of global interaction.

Individual lives do not ‘take place’ in a single geographical location, their episodes are increasingly dispersed. It is only logical that this revolution also demands a new type of biography: not a linear narrative based on sequential chapters, but a layering of simultaneous lives that are now lived in a range of fundamentally different cultures and environments, each engagement profound enough to require its own examination.

In that case, the single memoir becomes an implausible model, it needs to be replaced by a cluster – memoir… a stacking of almost independent stories that reconstruct the internal coherence, causalities, influences, encounters of each separate life.

This is the initial hypothesis on which this course is based. Out of a potential maximum of 10, it will focus on “3 lives”, on Germany, France and Russia and inventorize and interpret the experiences, characters, precedents, traditions, practices, histories in each, as crucial components of a new kind of cumulative identity.

Course Requirements:

Students are required to attend all lectures and submit a term project.

Lectures: To receive credit for the course, students are required to attend three scheduled lectures on April 6, 13, and 27 from 8:00 to 10:00 AM EST. Students interested in enrolling should ensure that they are able to attend all lectures. This course is not open for auditing.

Term Project: Students will develop an original geaugraphic project to be submitted at the end of the term. Students will conduct an exercise in architectural and urban research, taking their local context as subject. Students will devise and present a theoretical explication of their local conditions and their own synthesis of its “uniqueness”. Further details to follow.

NOTE:

If you are interested in enrolling in this 1-unit course, you should add the course to your Crimson Cart. You will officially be enrolled in the course at a later date, and you will not need to file a petition to exceed maximum units if this course would put you over your limit. However, students who enroll in this course would be charged extra tuition if they would exceed the following units by degree program:

20 – MDES

22 – MDE

24 – all other GSD programs

If you are a concurrent student, you would be considered among those who would be charged extra tuition if this course would mean that you would exceed 24 units.

As it is a module 2 course, please be sure that you have added this to your Crimson Cart by March 29.

This one-unit course will consist of three lectures over the course of the term. Lectures are schedule on April 6, 13 and 20 from 8:00 to 10:00 AM EST.

The United States and China

The United States and China are global economic and military powers. They have a rich history of commerce, friendship, alliance, and antagonism. Both countries have been shaped and re-shaped by the nature of their mutual relations. Their relationship is in crisis, the outcome of which will do much to define the world of the 21st century.

This University-wide course invites undergraduates and graduate students to examine together the present and future of U.S.-China relations in the light of their past. What are the enduring patterns and issues in China’s relations with the United States? How have these two countries perceived each other over time? How has trade defined the relationship from the Opium War to Huawei? How has war shaped experiences in the United States and China, and what are the risks of military confrontation today? What are the prospects for cooperation on global crises such as climate change? What is the role of American and Chinese universities, such as Harvard and Tsinghua, in shaping mutual relations in a time of global pandemic?

The course emphasizes active, participant-centered discussions of major issues, texts, and contemporary events, and will engage with Harvard Business School cases, experts on the U.S.-China relationship, and the rich resources of Harvard’s schools and the Harvard Center Shanghai. In their final project, students, working in groups, will address a central challenge in the Chinese-American relationship and propose a solution.

This course has an enrollment cap, so to be considered, you must request permission to enroll and rank your choices through my.harvard by 11:59 p.m. Tuesday, January 19, 2021. The Gen Ed lottery will run Wednesday, January 20, 2021, with approvals and denials sent out no later than 11:59 p.m. that day. Visit the Spring 2021 Gen Ed web page for more information and step-by-step instructions.

You are expected to attend class synchronously weekly at the time listed above. You are also expected to attend a weekly TF-led synchronous section meeting that will be based on your preferences and scheduled after the enrollment deadline.

This is a University course. All students should enroll in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences version of the course, GENED 1068.

Other(ed) Architecture: Coloniality, Subject, and Space

The aim of this seminar is to think critically about the authors and agents of architecture and the built environment. In examining relationships between ideological constructions of the modern “subject” and the physical constructions that shelter and house those subjects, we will ask: What counts as “architecture” and where do we find it? We will explore how architecture mediates between the project of modernity/coloniality and its silenced and invisible(ized) others. Furthermore, we will explore how space-making and othering are foundational to the project of modernity, and are intimately present in architecture’s technocratic canonization. We will question the subject of architecture: “How individuals are rendered as laborers, domestic workers, or immigrants in legal and cultural terms, and how the architecture of the camp, detention centers, plantations, and others solidify the symbolic and lived forms of these positions”. We will look at how the ideological project of modernity necessitates a colonial understanding of architectural space, and how difference and othering are built and made in/through space.

Through theoretical and historical texts, we will consider the lived-experience of subjects and discuses alternate archives of architectural knowledge production, particularly when looked at from its silenced margins. The aim is not to diversify a set of teaching materials in order to include “non-western” geographies, but rather to question the underpinnings of the discipline in the first place.

The semester is structured around 6 “frames”, each represented by two spatial typologies. Throughout, we will aim to think about these spaces and their associations with modalities of dispossession, resistance, and epistemic violence of silencing in multiple ways.

• Domestication – kitchen / gated enclave

• Circulation – infrastructure of movement / (slave) ship

• Extraction – plantation / factory and ports

• Bordering – walls and partition / street and threshold

• Detention – (refugee) camp / prison and detention center

This is a reading seminar, focused on in-class discussions of assigned texts. In addition, some weeks we will also focus on a film, fiction, or visualization project connected to the discussed theme. Assignments will be structured as short progressive writing exercises, culminating in a final research paper or annotated bibliography.

Independent Study by Candidates for Master’s Degrees

Students may take a maximum of 8 units with different GSD instructors in this course series. 9201 must be taken for either 2, or 4 units.

Prerequisites: GSD student, seeking a Master's degree

Candidates may arrange individual work focusing on subjects or issues that are of interest to them but are not available through regularly offered coursework. Students must submit an independent study petition and secure approval of their advisor and of the faculty member sponsoring the study.

The independent study petition can be found on my.Harvard. Enrollment will not be final until the petition is submitted.

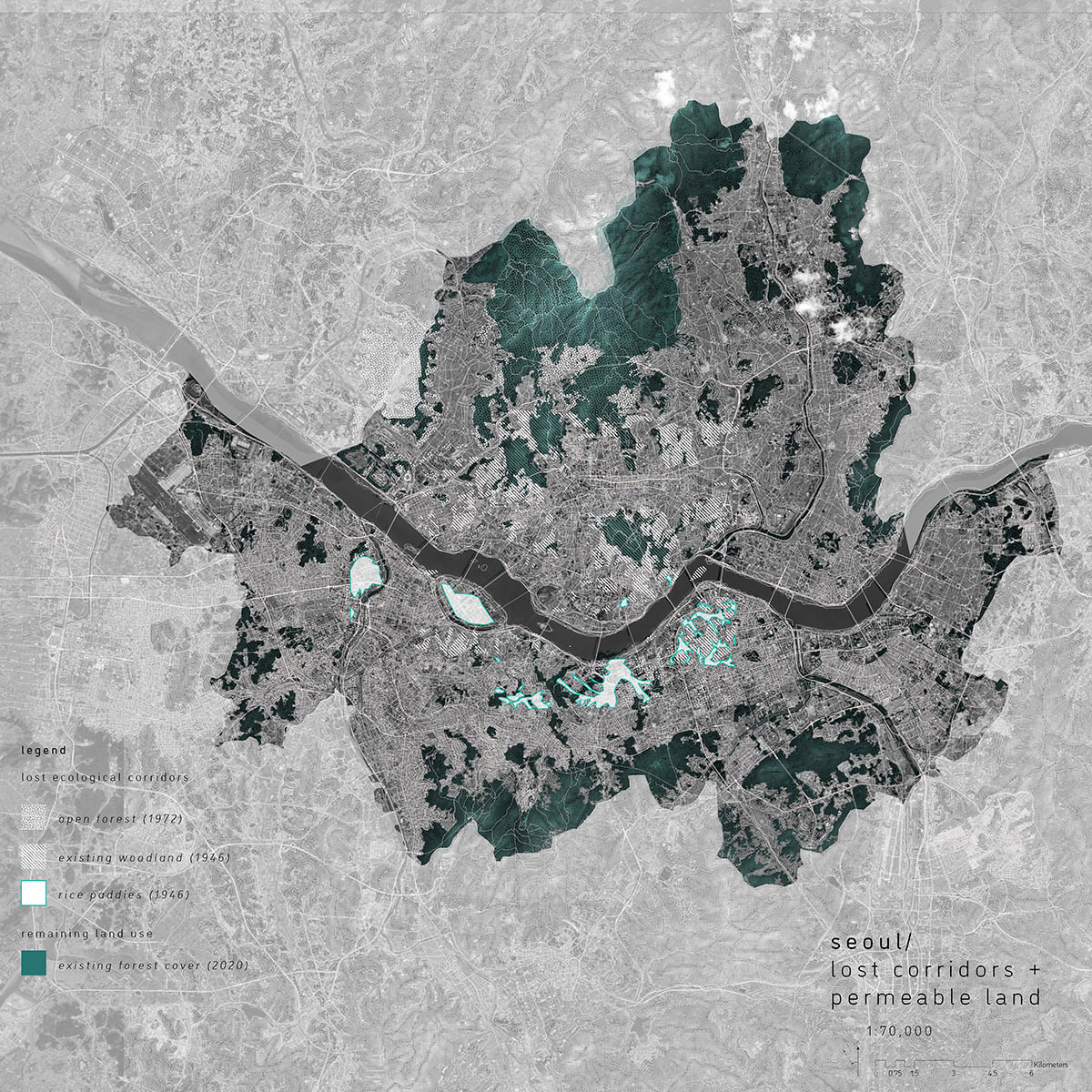

Rewilding the Urban Block: Constructing Permeability through Artificial Ground

Kari Roynesdal (MLA I AP/MUP ’21)

This project seeks to increase urban permeability in Seoul and Boston through the creation of an anthropogenic concrete subsoil, where over time, new geological layers below the surface transform to raise the water table along the edges of the Gangnam superblock in Seoul and Columbia Road in Boston. Rather than emphasize a pure reduction in impervious surface on these sites, this project investigates a deeper sectional analysis of urban ground, proposing a reuse of concretized infrastructure, processed to form a new permeable material. Over the course of several years, a deep section of Seoul and Boston shows a shifting and dynamic subsoil layer, shaped by runoff and hydrological processes, gradually connecting and raising the water table over time.

Both sites in Seoul and Boston share a past connection with muddy soils, such as rice paddy fields or marsh ecologies. With urbanization, these cultural landscapes have been erased from the ground, covered with concrete, and with climate change, have contributed to increasingly worse cases of urban heat and flooding. By analyzing existing land use, zoning, and development patterns in Seoul, a strategy emerges for which sites along the Gangnam superblock become ripe for densification and micro-watershed re-development. In Boston, existing vacant lots along the Dorchester Road corridor become activated as micro-wetlands and public gardens, in a context where public green space is rare and typically left unrealized. In the end, the project employs a similar urban strategy for two highly distinct sites, engaging a deeper sectional understanding of urban ground.

A Generosity Beyond Means

Jonathan Ng (MArch I ’22) and Edda Steingrimsdottir (MArch I ’22)

Mass housing faces the persistent challenge of creating economically accessible living spaces in increasingly densely populated cities. Housing units are often devoid of elements that contribute to one’s quality of life, being perceived as indulgent rather than essential. Through the manipulation of the ground, the interior wall, the facade and the roof, this project creates the perception of an expanded lived space.

In contrast to the densely packed triple-deckers in Boston’s Jamaica Plain (JP), the four housing bars of this project are lifted to create a generous open ground floor. Within four housing bars, the units are deliberately arranged heterogeneously, resisting the overly hierarchical or repetitious nature typical of housing blocks. The manipulation of interior walls creates spatial generosity unique to each unit type.

The facade is not just an external face for the public. It is a projective frame through which residents can establish connections beyond the limits of their units. This evokes a new definition of community, one that transcends proximity and forges new relationships from within, across, and beyond each unit.

The roof of the four housing bars is unified by a spherical subtraction, inverting the typical condition of a perimeter by establishing different horizon lines throughout the roof. It offers a generous new private ground for residents to form connections to the horizon, the sky, and the city beyond.

This project invites us to consider how the manipulation of space can be used to enhance our quality of life. It shifts our perception from an absolute scale or material wealth to the relationship between the subject and their surroundings. Expanding our definition of a quality living environment to one no longer limited by economic ability, the project provides for all, a generosity beyond means.

Independent Thesis in Satisfaction of the Degree Master in Landscape Architecture

Following preparation in GSD 9341, each student pursues a topic of relevance to landscape architecture, which must include academic inquiry and design exploration.

Thinking Through Soil: the earth in the herbarium

Every material process that shapes the construction of the urban environment passes through the soil at some point. In Thinking Through Soil, we will use the process of soil formation as a critical lens to trace the politics and material contingency of the urban environment.

The goal of this course is to familiarize ourselves with the fundamentals of soil science and soil theory, in order to think in new ways about the geos of design. As a material that lies at the intersection of the biological and geological sciences, this kind of thinking requires us to engage with the categorical boundaries that have historically shaped soil knowledge. By learning where these boundaries are and how to navigate them, we will become better equipped to make design decisions, and think critically about larger environmental issues such as climate change, wastewater agriculture, and local biology.

The course will begin with seminar style discussions around key texts that frame an analytical approach to the science and politics of soil knowledge. Here we will encounter recent critiques of the politics of soil by queer and feminist materialist scholars such as Vanessa Agard-Jones, Mel Chen, Elizabeth Povinelli, and Kathryn Yusoff have identified the geos as a crucial source of power distinct from the bio-political, and yet animated by the same ontological cut that distinguishes between them.

Through guest lectures by soil scientists, historians, and botanists, we will also learn more about how soil works, how it is understood empirically, and how it has been delineated as a natural historical object since the 1880’s. Through these engagements with both humanities and science scholarship on soils, we will begin to try to imagine what a different conception of soil might mean for our design practice, and for a broader commitment to decolonial geo-environmental justice.

Final projects in this course will be done in partnership with the Harvard Herbarium. In approaching this herbarium’s vast and immaculate digital collection, we will ask a simple question: where is the Earth in the Herbarium? To put the question another way, in preparing the millions of catalogued plant specimens that fill national herbariums around the world, and our own herbarium here at Harvard, what happened to the dirt? Predating the university itself, the longevity of the herbarium as a form means that it has not only accumulated plants but has also accumulated our ideas about plants, and through a strange kind of absence, our ideas about earth as well. Through a series of presentations and workshop style feedback sessions with the seminar as a whole, students will build a final research project reconnecting a plant with its missing soil. In this phase of the course, we will engage directly in the representational questions our readings have lead us to, taking seriously the old architectural maxim that drawing is thinking. Final projects will consist of student-selected projects based in the digital collection of the Harvard Herbarium, and will require us to imagine more clearly the missing earth in the herbarium.

For a preview of last years final projects, see: https://thinkingthroughsoil.studio/

?

Note: the instructor will offer live course presentations on 01/19-01/21. To access the detailed schedule and Zoom links, please visit the Live Course Presentations Website. If you need assistance, please contact Estefanía Ibáñez.

Altered Rural and Urban Landscape Restoration

Highly altered and often engineered rural, coastal, and urban landscapes are difficult and expensive to adapt to the realities of climate change. Food production systems in rural America characterized by drainage infrastructure (tiles, ditches, dams, pipelines, irrigation units) are old and/or inefficient. Urban centralized utility and transportation infrastructure is old and failing, vulnerable to climate change, and antithetical to restoring natural function. Coastal areas suffer from upstream pollutants from tributary rivers and as border lands are increasingly impacted by sea level rise and catastrophic storms. Repairing, rebuilding, and extending existing infrastructure in these landscapes is not an option if we are to sustain ourselves, anticipate and mitigate climate change, and support and restore nature. As a later-sequence ecology course on natural processes and built environment issues in the coastal zone/nearshore environment and rural landscapes, this course complements existing GSD emphasis on introductory ecology, terrestrial systems, and freshwater wetlands. The course focus on ecological design and management of rural and urban landscapes is highly relevant to current/future climate concerns with sea level rise, stormwater management and flooding, drought, energy infrastructure, transportation infrastructure, and food supply.

Apfelbaum brings expertise in ecological applications to achieve restoration objectives, stormwater management, and risk assessment. Zimmerman brings expertise in assessment of and solutions to the ecological impacts of urban development from CSOs and stormwater to energy demand, groundwater, and equity issues. Parsons brings expertise in estuarine ecosystems and biodiversity, toxics and sediment management in urban ports (including New York City, Boston, Philadelphia/Wilmington, Baltimore), ecologically-based engineered solutions to habitat loss including islands, coastal wetlands, barrier beaches, and peninsulas.

Learning Goals:

The course takes advantage of the instructors knowledge as practitioners. From people issues and conflict to dealing with conventional approaches to engineering and design, regulation, and anticipating the consequences of climate, the course will give students a real world look at how to assess existing rural and urban infrastructure and how it impacts natural systems. They will understand the principles and methods of evaluating altered systems practiced by the instructors, learn to apply them in their own work, develop natural restoration alternatives based on their evaluations, and become familiar with the issues, regulations, and obstacles to their implementation.

Course structure:

– Fixed Synchronous meeting: Thursdays 10:00am-12:00pm (120 minutes). Entire class meets online

– Flexible Synchronous meeting: Either Wednesday mornings 9:00am-10:00am or afternoons 3:00pm-4:00pm (60 minutes). Focus groups, case study work, Student presentations, additional lecture material

– Asynchronous Content (as necessary based on availability – 60 minutes). Team projects, lab sections, small groups

– Preparation Time: 6 hours. Reading, writing, case studies, research

?Note: the instructor will offer live course presentations on 01/19-01/21. To access the detailed schedule and Zoom links, please visit the Live Course Presentations Website. If you need assistance, please contact Estefanía Ibáñez.

Plants and Placemaking – New Ecologies for a Rapidly Changing World

In the face of crises spanning pandemics, political turmoil, and the rapid degradation of the planet’s natural systems—all with a backdrop of human inequality—the power and importance of our work as landscape architects is becoming clearer to those outside the profession. Erosive pressures associated with changes to climate have placed global plant communities under constant assault, yet abundant and resilient life still adapts and flourishes in most places. This course will encourage students to observe these patterns and to learn from context so that we can place the healing and restorative qualities of plants, essential to sustaining life on this planet, in the foreground of our work as leaders in this incredible and dynamic profession.

A frequent criticism of new landscape architects emerging from academia focuses on their limited practical knowledge related to plants and planting design. Let’s change this. We share a collective responsibility to lead and teach our peers, patrons, collaborators, and the public of the vital role that plants and well-considered planting design plays in shaping the human experience.

To reimagine the revegetation of a place after catastrophe or amidst the pressures of growth and large-scale human movements, we must first understand context by digging into the past to examine what ecologies were there before the present state occurred. With these informed perspectives, we can begin to repair fragmented natural systems, preserve (even create) habitat, sequester carbon, and buffer communities from destructive weather and climate—all while embracing the realities of how people gather, work, and live. Plants define the character of place; they shape who we are and who we become. We must get this right or the same patterns in more chaotic contexts will simply reemerge.

This course is open to those who crave a creative and interpretive, yet always pragmatic, approach toward utilizing plants to create landscapes that actively rebuild systems stretching far beyond site boundaries.

Expressive and iterative weekly exercises will encourage rapid design that inspires students to explore natural and designed plant communities. Conventional and non-conventional planting typologies will be examined. Together we will seek new and innovative ideas for how to restore biological function to the land. We will use empirical observations and investigations to explore multiple-scaled thinking about plants and their environments, including cultural and vernacular attributes. This course will not be a comprehensive overview of the horticultural or botanical history of plants; however, it will reinforce important methodologies for how to learn and research plants that can be translated to any locale, by studying individual vegetative features and characteristics. Together, we will translate these investigations into design languages that can be applied in future design work.

Products of the course will include mixed-media drawings that explore typologies of designed and non-designed plant communities. Videos, photographs, drawings, sketches, and diagrams, as well as conventional plans, sections, and elevations, will be the vocabulary of the course.