Collins Reservoir

Kent Hipp (MLA I ’17)

In response to climate change and rising sea levels, this project re-imagines Miami Beach’s Collins Canal as a stormwater reservoir with the capacity to alleviate flooding and generate new urban form. First cut in 1912 to move produce across the island, today the Collins Canal abuts a number of public facilities – schools, parks, gardens and memorials. The reservoir links these valuable sites, and creates a continuous public realm, which is activated by the daily and seasonal changes of the ocean. Adjustable tidal gates placed at either end of the canal are synchronized with pump stations – allowing for the adjustment of water levels within the canal. Prior to a large rain event, water could be set a low elevation to provide storage for stormwater runoff. The reservoir’s topography responds to this fluctuation, creating micro-climates for cypress and mangrove plantings, as well as interesting spaces for walking and gathering. Along this blurred water’s edge, new elevated buildings connect the city fabric to the reservoir and create an urban district which is adapted to climate uncertainty.

Flamingo Waterpark

Izgi Uygur (MLA I ’18)

In subtropical climates such as Florida’s, there is either too much water or not enough water. It is a place of extremes, as well as a region confronting changing climatic conditions and highly stochastic weather patterns. This project balances freshwater availability seasonally by defining the effects of increased salination on varying types of water due to sea level rise. It is possible to address the freshwater shortage by using a series of stormwater retention tanks in Flamingo Park.

As the only large and open landscape in the city, Flamingo park can address two hydrological issues: the fluctuation of freshwater availability and the threat of sea level rise, without drastically changing its existing character. This helps not only to save energy and water by decreasing the stress on desalination facilities, but also supports the governmental plans of increasing green spaces by irrigating park’s native and aesthetic vegetation. Instead of elevating the entire park, this scenario proposes to place the tanks on an altered topography above the projected flood lines, where the landforms also offer dry ground for post-storm relief.

This project imagines strategic interventions that makes the park a part of the municipal infrastructure. An underground network of pipes that connects the tanks within the park can not only help to irrigate the park trees, sports fields and alley trees, but also the green spaces around the park. Overall, this can contribute to individual irrigation and vegetation control. In addition to its role as added infrastructure and public space, the elevated cisterns introduce a new ground for varied botanical landscapes and suggests a new future for the park that combines city’s history of botanical gardens and its planned sea level rise adaptation.

Read about this project in The Miami Herald .

Miami Beach Baywalk

Chris Merritt (MLA I ’17)

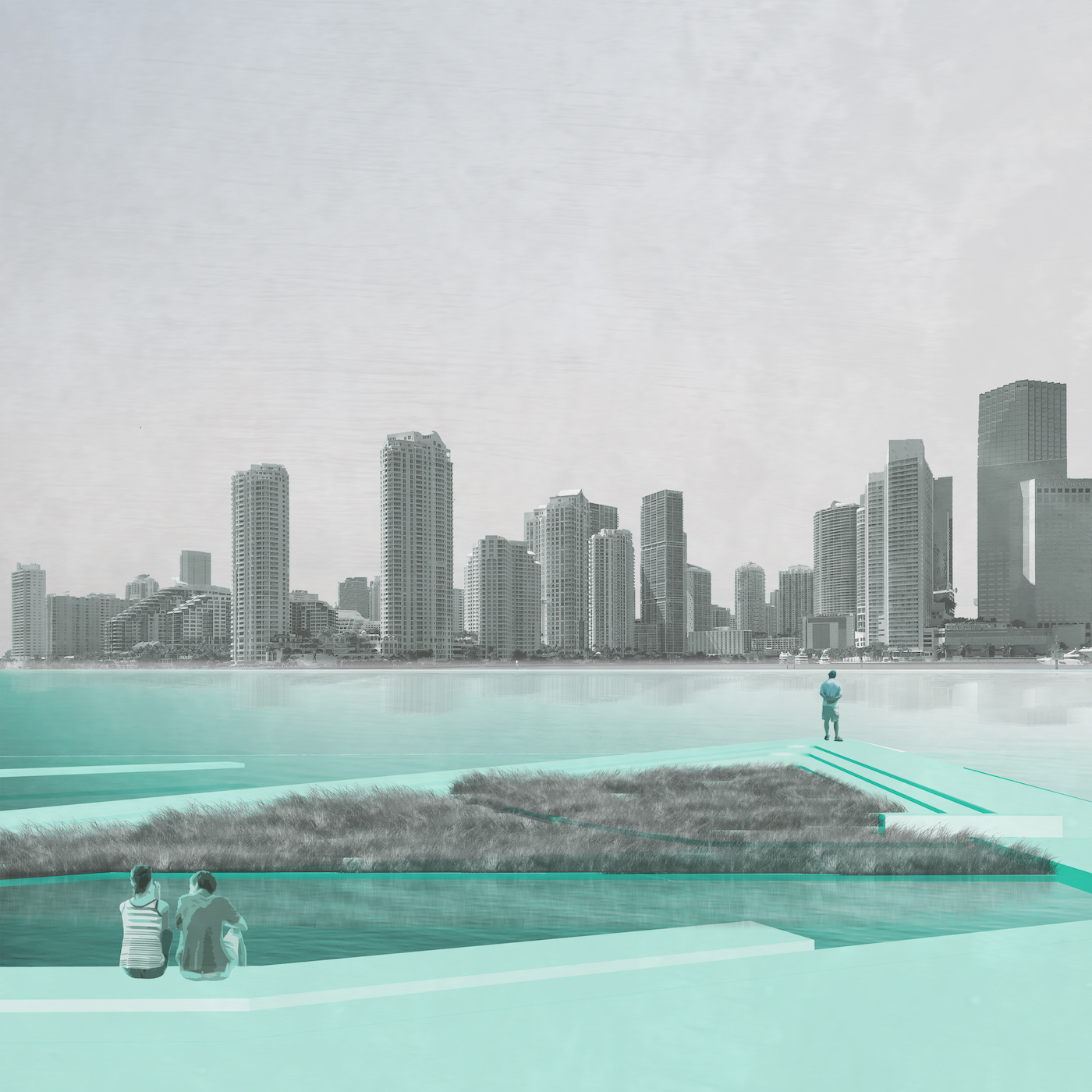

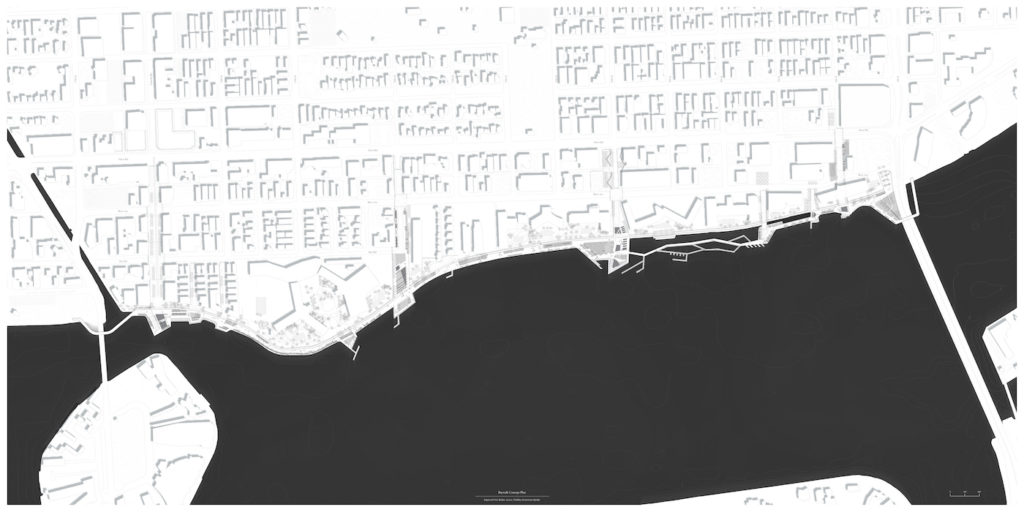

The Miami Beach Baywalk will serve as an infrastructure for storm surge and stormwater quality while functioning as a new public space for Miami Beach. Sea level rise projections indicate the Bayside is the most vulnerable on Miami Beach. In addition, as this area has the lowest elevation, the city’s stormwater naturally drains and is pumped to the Bay. Recently, the City of Miami Beach has installed pumps along the Bay to handle the pressures of large volumes of stormwater runoff. The new Baywalk is designed to alleviate stormwater quality issues while enhancing the quality of the public realm. The Baywalk will serve as a continuous, connected, and visible system of plazas and walkways that return the Bay as a destination to the city.

Background

The emergent topic of urban adaptation to the effects of climate change is among the more pressing areas for those engaged in the design of the built environment. Among the more extreme cases in this regard is the present status and uncertain future of South Florida’s coastal communities. In Miami Beach, the low-lying coastal conditions and singular cultural heritage resist the types of massive civil engineering projects that have recently been proposed for other major international cities. As Miami’s coastal barrier islands form one of the most recognizable and singularly valuable cultural landscapes in the world, the conditions in Miami Beach reveal the potential for ecological and infrastructural strategies to act as alternatives to large single purpose engineering solutions. Today, the structuring elements of urban form in Miami Beach are quickly becoming the pumps, seawalls, road elevations, artificial dunes, and sacrificial floors that are deployed in response to rising sea levels and increased storm events. How can designers act and what is the role of the landscape architect in this urgency for urban adaptation?

Miami Beach is a construction. It was drained, defoliated and developed through the promotion of its climate; perfect temperatures, ideal beaches, seamless horizons, warm water, and unencumbered escape. The porous oolitic-limestone that underlies Miami Beach makes the city particularly vulnerable to sea level rise as seawalls are simply ineffective, and multiple pumps are only temporary measures that help municipalities cope, but not adapt. With the pending dimensions of sea level rise, water has become a threat, as it is generally accepted that Miami Beach will be subject to rising waters and flooding – not to mention potential devastation from incoming and worsening storm tracks. With the conservative estimate of a 2ft rise in our oceans by 2060, Miami Beach will be underwater and Miami shorelines will recede up to 2,000 ft. (National Climate Assessment Data). While hard infrastructure, raising roads, and proliferating pumps are managing the issues and allowing the city to cope, the prospects and opportunities of future scenarios remain unknown.

Urban adaptation to ambiguous sea levels is creating a new form of public space, and the application of resilience as a measure of success must respond to and address these new public parameters. Given the reliance of South Florida’s economy and identity upon the specific landscape conditions of Miami Beach, this project proposes to use green infrastructure, landscape ecology, and cultural heritage as potential responses to the looming threats associated with sea level rise.

Project Description

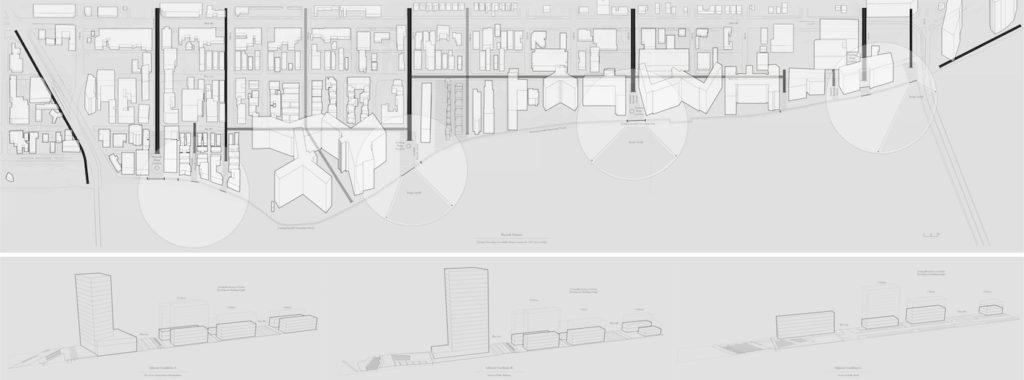

A cross section through Miami Beach reveals a slight slope from the nourished ocean-side beaches and Ocean Drive down to the Bay. As the commercial back-bone of the city and lowest in elevation, this area is Miami Beach’s most vulnerable, and current target for intervention by the City. The natural topography and recently installed pump infrastructure carries the island’s stormwater to the Bayside where it is pumped back to the Bay. Through the aggregation of private condo development common to Miami Beach, a wall has been created that separates the city from the Bay with limited access. The proposed Baywalk project outcomes are threefold: 1) introduce an infrastructure for managing stormwater quality, 2) mitigate effects from storm surge, and 3) renew the public realm with access and visibility to an ecological and culturally vibrant landscape.

The proposed new Baywalk is a continuous linear public space connecting Miami’s South Pointe Park via the 5th Street Causeway to Maurice Gibb Park to the north. The Baywalk also reaches back into the city, literally and figuratively, utilizing City owned parcels and streetscape improvements to provide better access and visibility while managing stormwater before it reaches the Bay. Previously, private condos along the Bayside have fragmented the Baywalk – leaving no connections between each development. In addition, with the introduction of new pump infrastructure at the Bay, an opportunity exists to leverage this system for a model of urban adaptation to sea level rise.

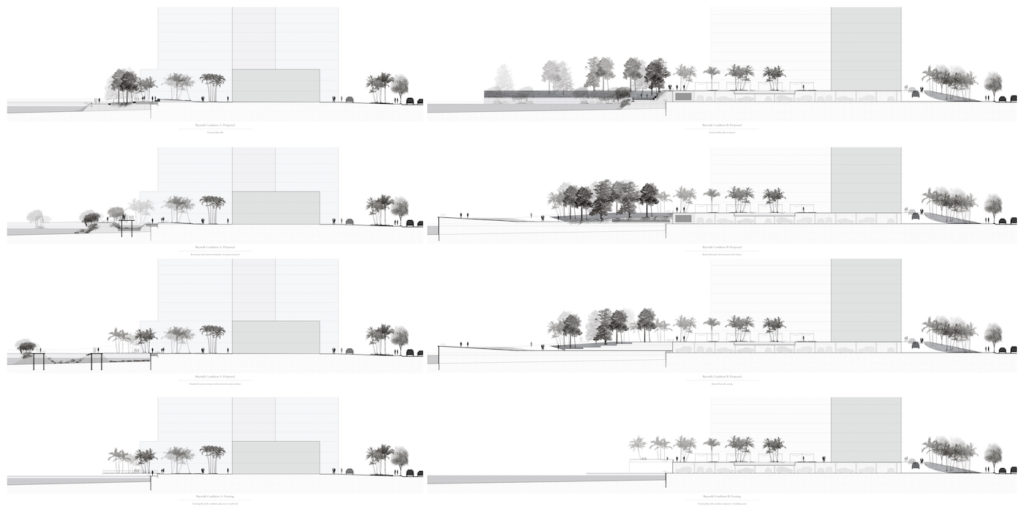

The framework of the Baywalk starts with recognizing an opportunity for increased public space exists at each of the existing and proposed pump station locations. These locations are utilized to bring stormwater runoff from the city through a system of separation, filtration, and aeration before releasing water into the Bay. The Baywalk is not just a utility; it also enhances the public realm experience. The pump station locations are transformed into large plazas for gathering that are distributed evenly and provide a unique experience along the Baywalk. This new public space exists at the terminus of Lincoln Road, 14th Street, 10th Street, and 6th Street. The plazas are linked together through a linear Baywalk that removes the existing divide between private and public.

The condos along the Bay in Miami Beach sit on a podium filled with parking that creates a wall along the fragmented Baywalk. In some cases, the buildings have a simple retaining wall separating the Baywalk from the private terraces of the condos. This condition creates a separation that reveals the sharp contrast between the private condos and the minimal Baywalk – “the haves and the have-nots.” The proposed Baywalk joins the two spaces creating a seamless public realm that transitions from building to water through a series of terraces, slopes, walls, and landscape elements.

Miami Beach is a place for people watching and sun bathing; and for recreation and relaxation. The currently underutilized Baywalk is transformed into a public promenade where one can see and be seen. Utilizing the necessity for elevation change, varied experiences are created and rooms are carved along the Baywalk for smaller gathering and intimacy. With retail, dining, and entertainment, the Baywalk serves as an extension of Lincoln Road at the Lincoln Road plaza. And, by removing the divide between public and private and offering new access, the Baywalk serves locals in Flamingo Park. The extension of the Baywalk back into the city fabric offers visibility and a physical connection that ensures the Baywalk is built for everyone.

South Florida attracts residents and tourists alike for its subtropical climate. Combinations of unique species of flora and fauna are found in this geography that cannot exist elsewhere. In addition, the Bayside of Miami Beach was historically home to thriving marine habitats before the introduction of anthropogenic pollution and destruction. Therefore, the Baywalk is designed to accommodate habitat development for its ecological function and cultural significance. At each of the stormwater management plazas, vegetation is selected for its utilitarian function. In other areas, a cultural abstraction is utilized to create a “marine museum” or “ecological museum” that serve as a cabinet of curiosities along the Baywalk. Vegetation zones include pineland and hammock planters, temperate and tropical assembly gardens, a beach with an artificial dune, and linear mangrove habitats. The “marine museum” includes boardwalks through sheltered pools that enable stable habitats of seagrass, coral, sponges, and wetlands.

Through proactive measure Miami Beach can respond to the threats of sea level rise with opportunistic infrastructural intervention that also enhances the public realm. In a challenging political climate and market with increasing private interest, the City has to be strategic about investment in the longevity and quality of Miami Beach for the public good. A new Baywalk that manages stormwater quality, protects against storm surge, and enhances the public realm is a boon for visitors and residents of Miami Beach alike.

Ocean Court

Daniel Widis (MLA I ’16)

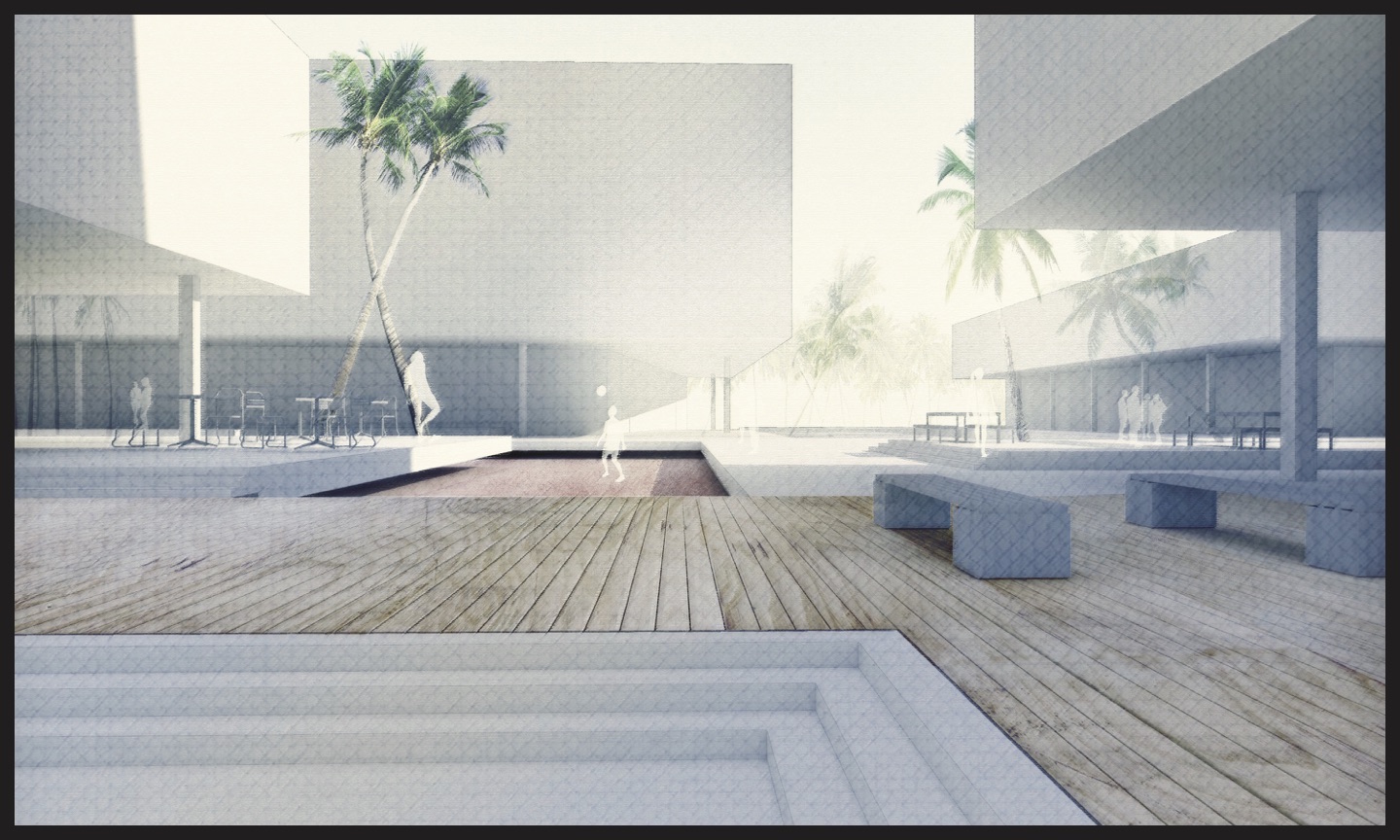

Tenuously positioned as an informal slip of sand and coral limestone, Miami Beach has been formalized into a rigid, urban landscape through decades of commercially driven development. The end result is a city devoid of genuine public space. When expressed, public space lands in the artless form of linear spaces running along beach-front properties. The inherent tension between public/private, formal/ informal is best expressed in these linear landscapes – spaces that are framed as pedestrian and civic, but at their heart are unapologetically commercial. The inevitability of sea level rise offers an invaluable opportunity to reclaim and animate the city’s largely forgotten public realm. Ocean Court revitalizes a neglected interstitial alleyway in a city desperate for functional community and civic space.

Higher Lanes and Public Planes

Myrna Ayoub (MArch II ’16)

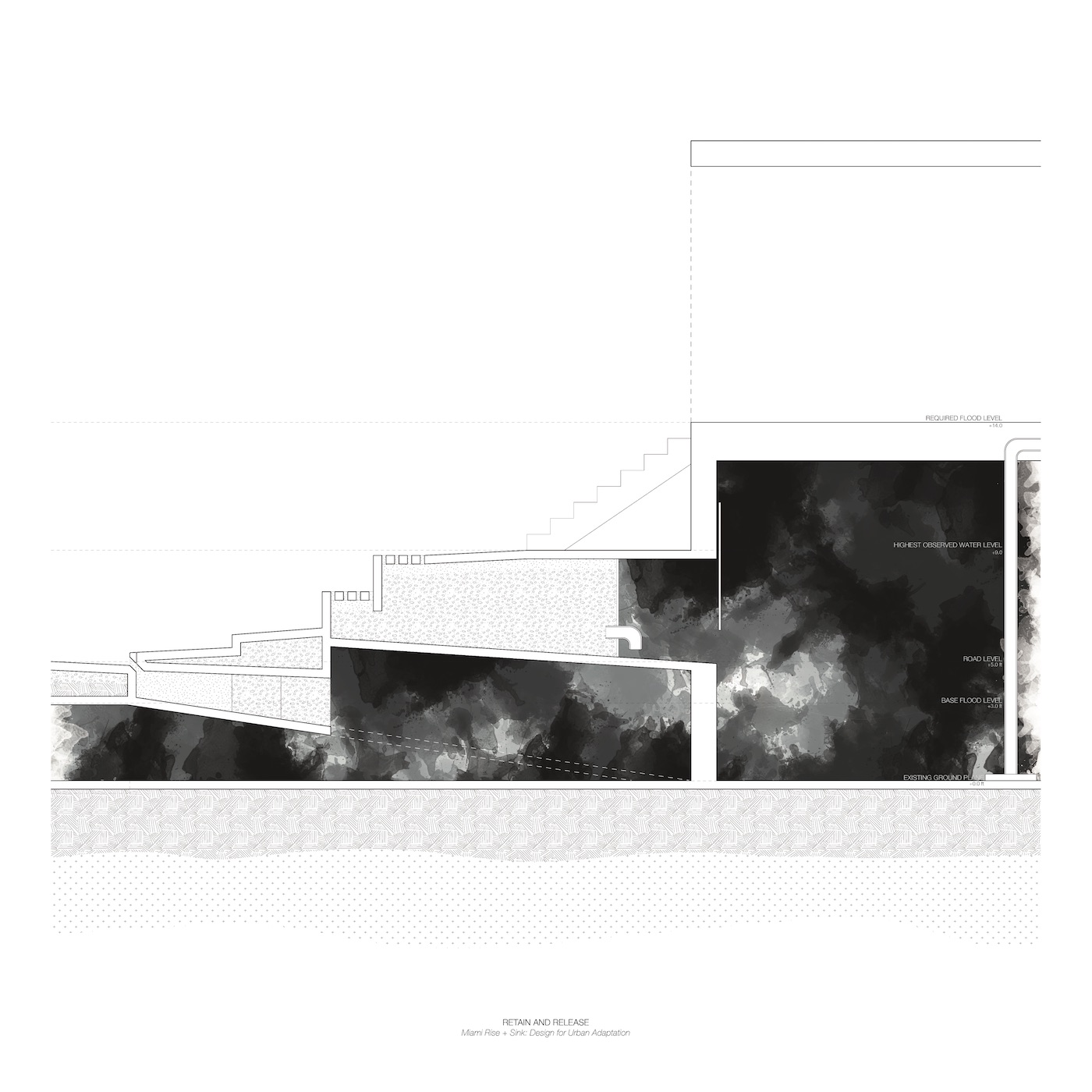

As sea-levels rise and the threat of flooding looms within South Beach Miami, new regulations and codes are responding through recommendations to elevate the city. The proposed flood level floor and raised roadway are an adaptation of elevation–a deliberate re-articulation of the ground-plane that creates a new urban threshold. By reworking these modifications, water can be absorbed, moved, or retained as opposed to shed, concealed, or pumped. The fluctuation of urban boundaries, manifest in the section in particular, reveals an exploration of levels that augment civic context. This project explores the potential manifestations for these new elevations through the study of three sites identified along the transect of 4th and 5th avenue. The typologies negotiate the parameters and accommodate the existing urban conditions to allow for the preservation of a dynamic/heterogeneous city and the resilience in the face of rising sea levels through the exploration of the urban section.

Hydrologies: This project explores section operations to maximize municipal stormwater management capacities. In the public realm, streets elevate with limestone-like fill to increase storage. New pervious ground cover materials slow runoff from overburdening existing drainage systems. In the private realm, new ground floors sit atop limestone filled “sponge pads” and elevated buildings cede ground to maximize sheet flow. In both realms, additional vegetation and their deep urban soils add stormwater infrastructure.

Spaces: The interior of the site is set aside for ecological performance. Low-maintenance native ecosystems are fostered to regenerate potential habitats and reduce open-space maintenance fees. Concentration of tree planting at the northern and southern tips suggest public parks and possible habitats that could spur from the alluvial channel. Topographical modifications foster the succession of native species. East-West corridors enable street tree planting schemes that organize and orient the block structure.

Infrastructure: This scenario views ongoing engineered infrastructures as a multi-layered system that provides pubic benefits and a new urban landscape. In addition to elevating the street roughly 5’ above current grade, mass transit is also introduced along 5th Street where it connects directly to the MacArthur Causeway. Pedestrian walkways and bikeways take precedence over vehicular traffic which is reduced in capacity and speed. Certain parts of the new ground plane are reimagined as extensions of public space.

Policies: Coordination between the public and private realms is paramount to creating seamless urban thresholds and transitions. A finer-grained zoning overlay map would be necessary to integrate suggested common flood elevations and regulate private properties to match such elevations. Where roads cross multiple jurisdictions, additional cooperation is necessary to ensure the successful design, construction, and maintenance of proposed section scenarios. FAR incentives on key corner properties would help initiate and accelerate their adaptive redevelopment.

Parametric Energy Simulation in Early Design

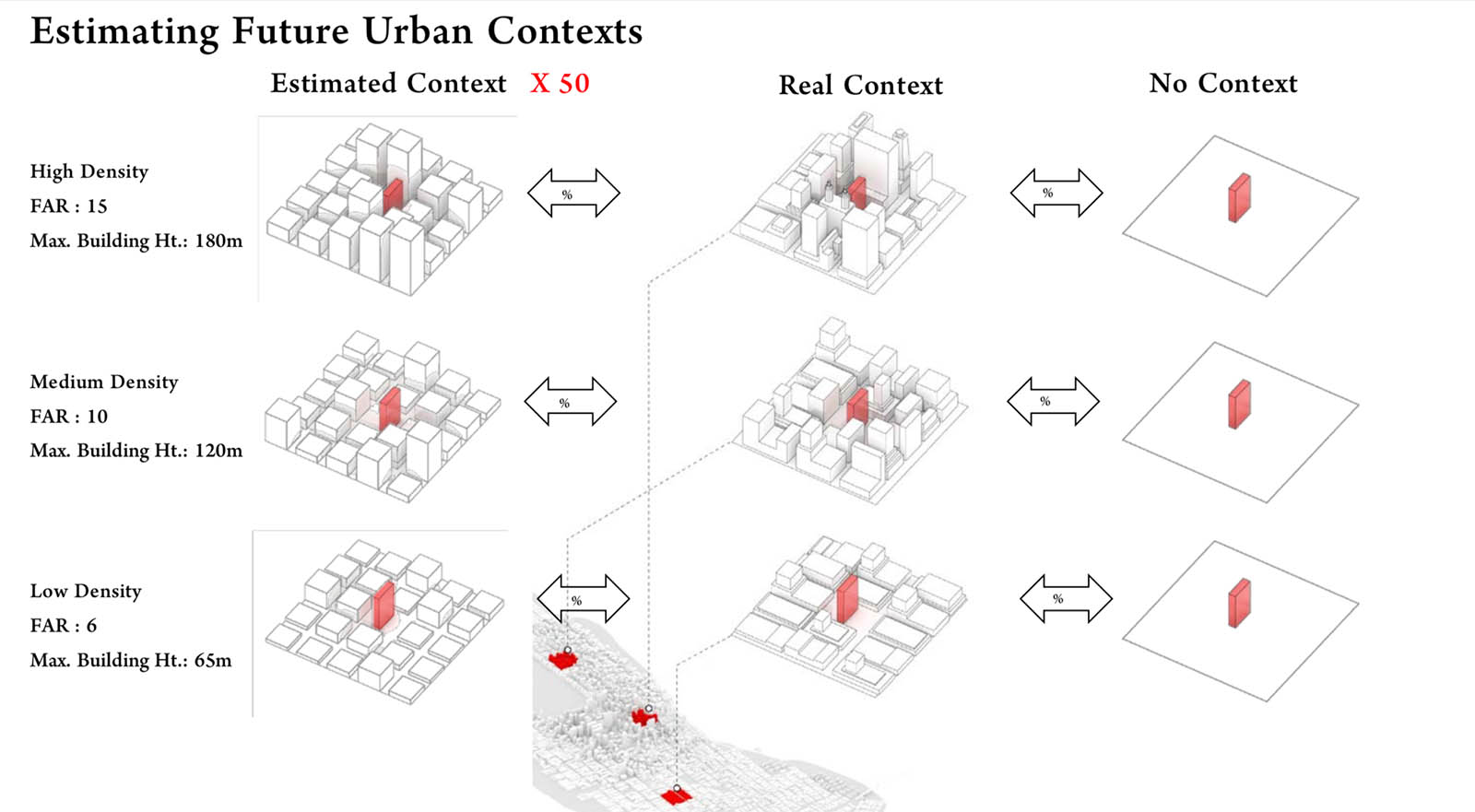

This project proposed a framework for the development of early-design guidance to inform architects and policy-makers using parametric whole-building energy simulation. It included a case study of a prototype multifamily residential building, using an exhaustive search method and a total of 90,000+ simulations. The authors performed a simple sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential of the tested design parameters on energy use intensity, which included WWR, Glass Type, Building Rotation, Building Shape, and Wall Insulation, in that order. They identified synergies and trade-offs when designing for different energy objectives, including (a) decreasing Energy Use Intensity, (b) reducing peak-loads, and (c) increasing passive survivability i.e., maintaining the safest interior temperatures in an extended power outage.

This project also investigated the effect of urban context as a source of sun shading and found it to have a substantial impact on the design optimization. Ignoring urban context in energy simulation, a common practice, would mislead designers in some cases and result in sub-optimal design decisions. Since in generalized guidelines the future building site is unknown, the researchers proposed and tested a method for generating urban contexts based on the floor area ratio and maximum building heights of an urban district.

Team Members

Holly Samuelson (Faculty), Sebastian Claussnitzer, Apoorv Goyal (MDes), Yujiao Chen (DDes), Alejandra Romo-Castillo (MDes)

Affiliated Publications

“Parametric Energy Simulation in Early Design: High-Rise Residential Buildings in Urban Contexts ,” Samuelson, H.W., Claussnitzer, S., Goyal, A. Chen, Y., Romo-Castillo, A., Building and Environment, May 20o1

“Parametric Energy Simulation of High-Rise Multi-Family Housing,” Samuelson, H.W., Goyal, A., Romo-Castillo, A., Claussnitzer, S., Chen, Y., Bakshi, A., Proceedings of Simulation for Architecture and Urban Design (SimAUD), Washington, DC, April 2015

Third Semester Architecture Core: INTEGRATE

Selected projects from Third Semester Architecture Core

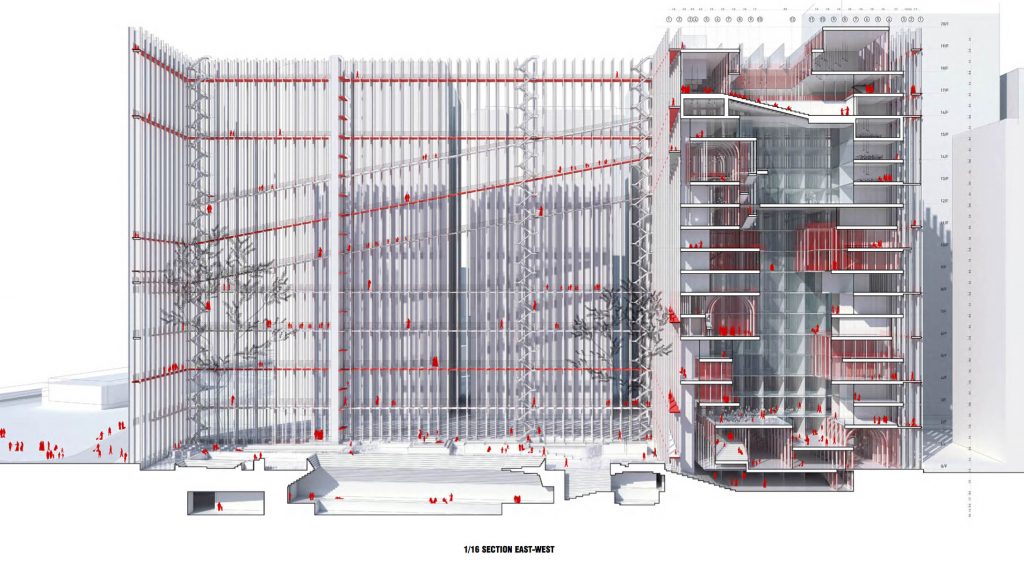

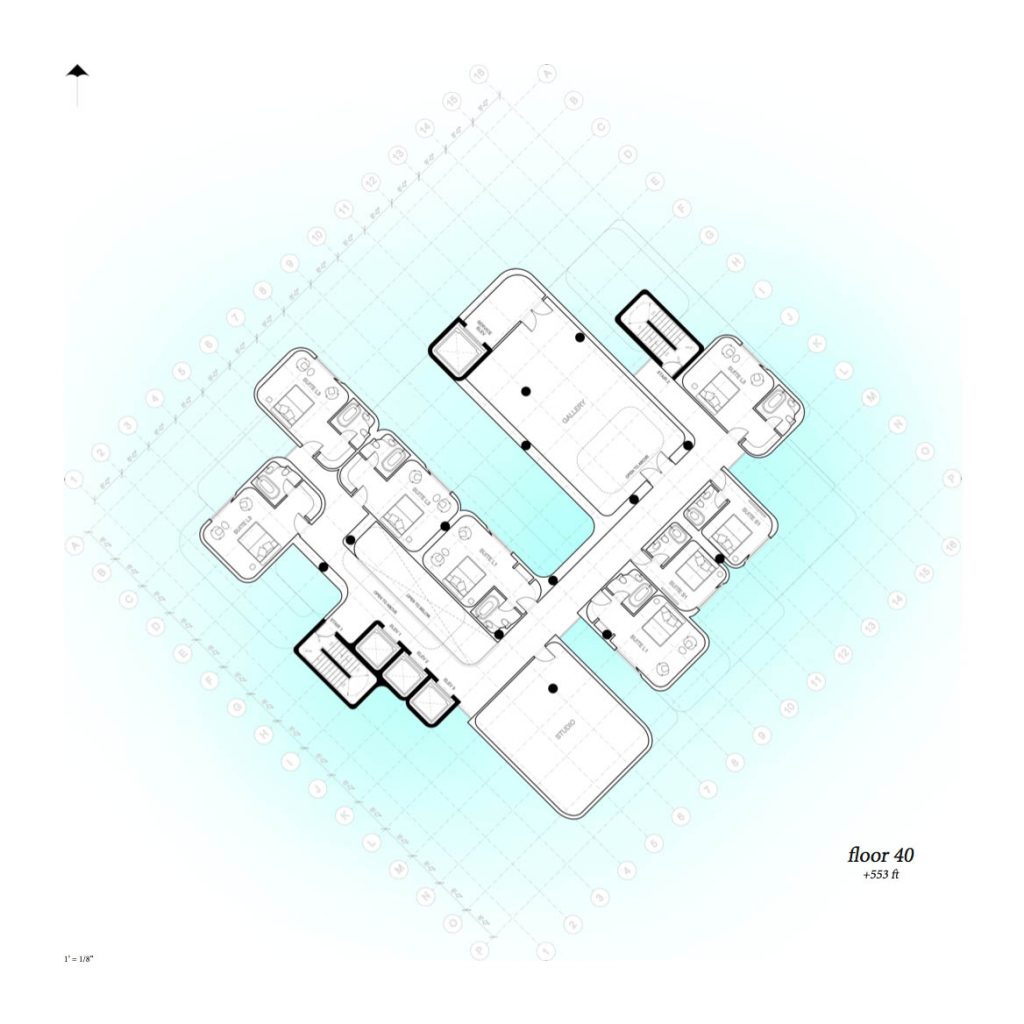

Bradley Silling (MArch I ’19)

Beining Chen (MArch I ’19)

Emily Ashby (MArch I ’19)

Khorshid Naderi-Azad (MArch I ’19)

Daniel Kwon (MArch I ’19)

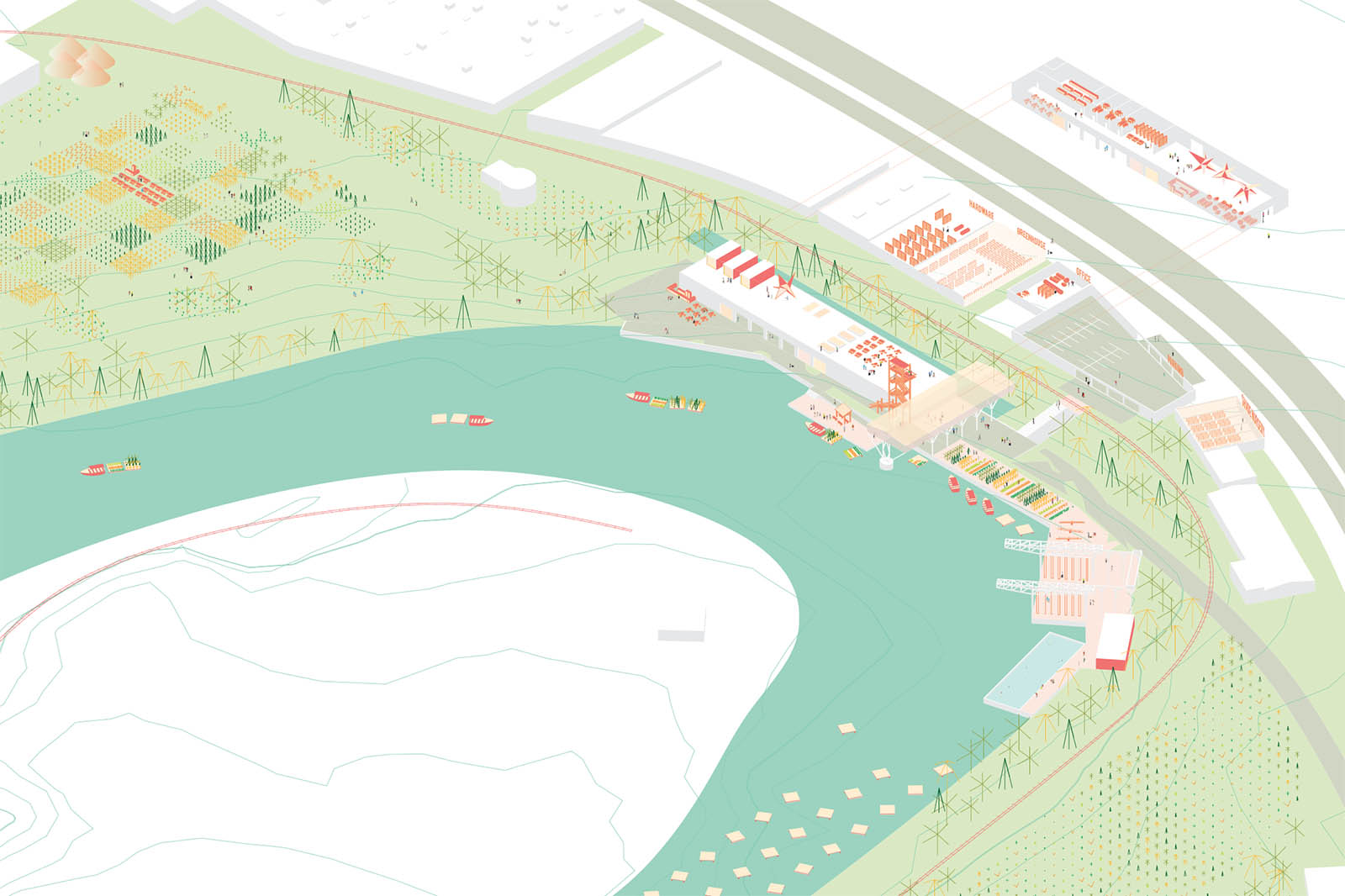

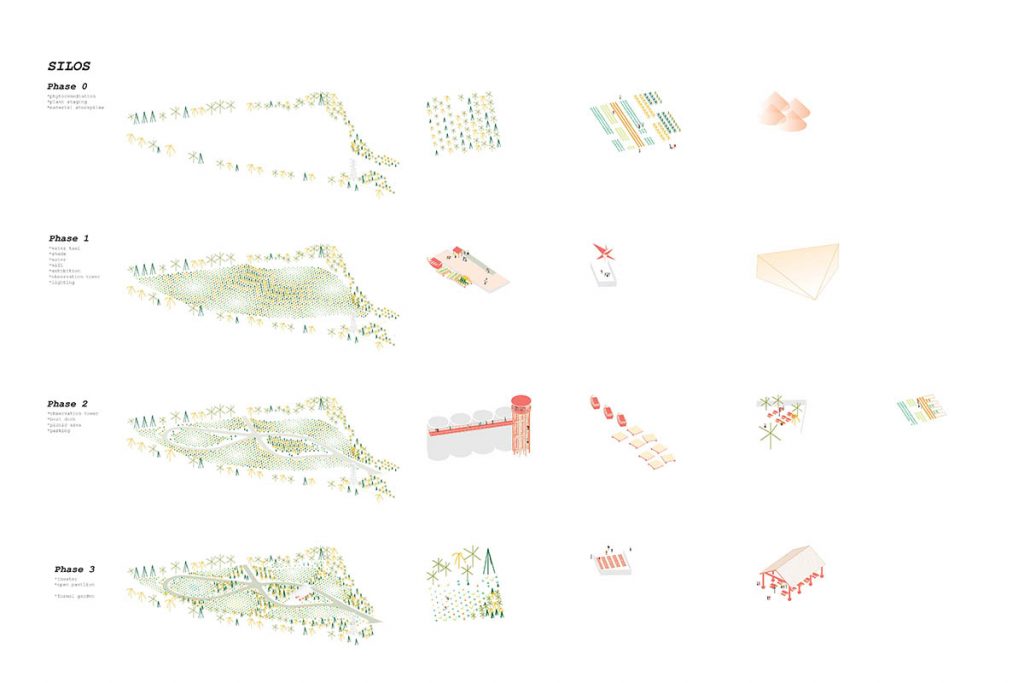

Re-Tooling Metropolis: Provisional Landscapes, Emergent Urbanism in Houston’s Eastern Bayous

Yuxi Qin (MLA I ’17) and Christopher Reznich (MLA I ’17)

Catalog of Parts

Yuyanguang Mou (MArch I ’17)

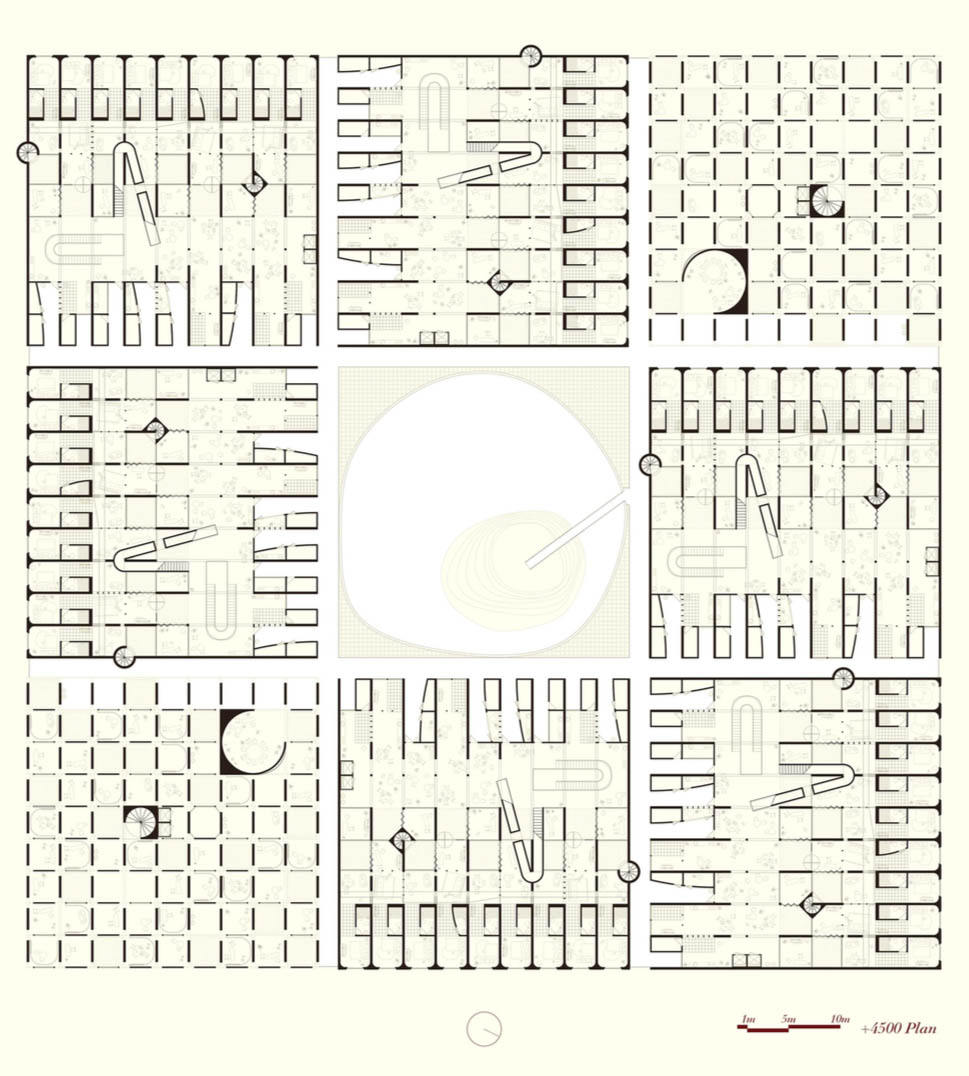

The ambiguity of tropical cities sometimes could be reflected through the flexibilities of its community structure and social relationships. The aim of the design as a housing block in the city center of Medellin, Columbia is to create a “catalog of parts”, a framework that could insert a new order into the community that offer both order and flexibility.

The design was composed by 3 squared elements: housing block, SOHO office, and community courtyard, representing the essentials of life components. The blocks were elevated, leaving the ground level only columns with differentiated shapes and orientations as a framework that offers opportunities for spontaneous organizations of outdoor social and commercial activities within this tropical context, as well as a more modest way of introducing a new order into the city.

Within the housing block, each unit was framed within a linear space of multiple programs, while the other linear orientation would then be composed of the same program of different units. The 2 orthodox orders offered the opportunity for the space in the housing units to operate in both directions, achieving both the individual procession of life behaviors as well as possibilities of shared communal spaces. The occasional disruption of the rigid grid such as the elevator, the trees, the stairs and slides leading up to the roof also reinforce the idea of cross-operating space.

The office space also bears the same thought as the walls in different directions have different width that indicate a dominant order and a penetrating one in the space. The joints of walls are cut open, offering a free-circulating space that could be organized according to the will of the user. Multiple spatial devices such as curtains and sliding doors are also play an important role in this flexible system.

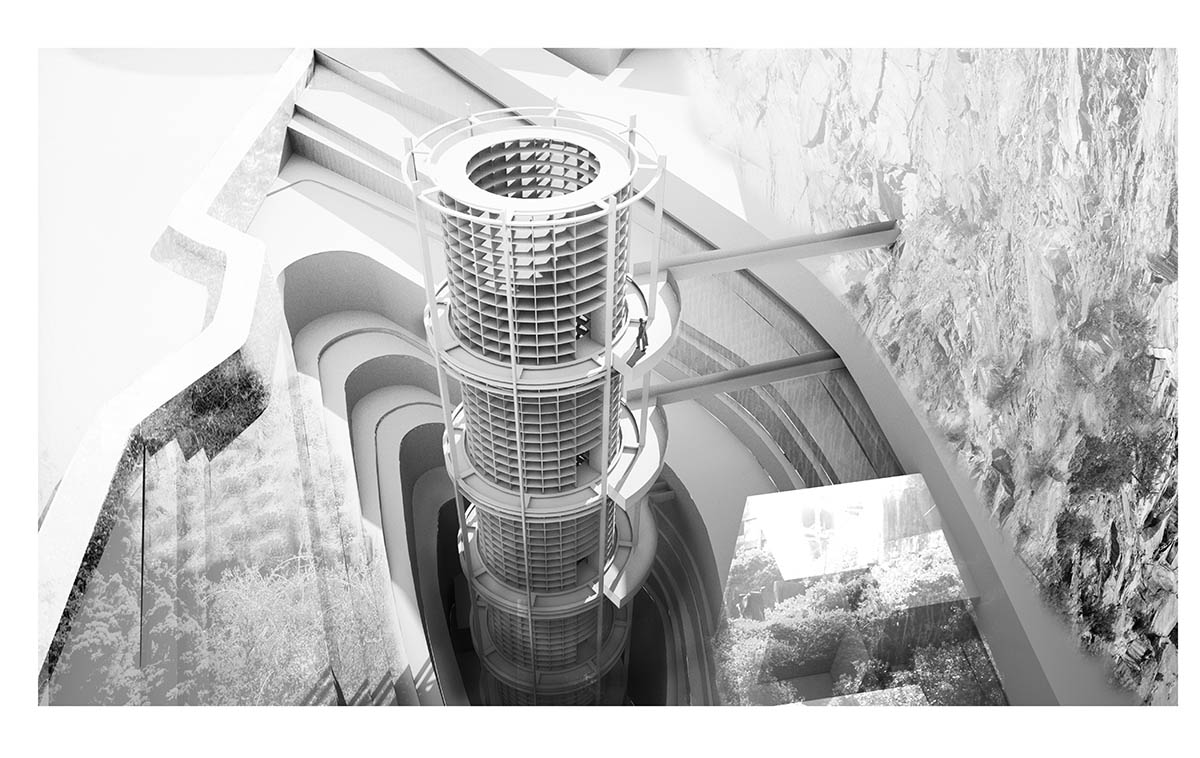

The Possibility of an Island

Andres Camacho (MArch I ’19)

Who would build the island? Would it be the Mitsubishi Group? The company who was complicit in the exploitation of labor, land, and extraction of coal in Hashima Island in 1890? Who would then leave abandoned and forgotten its workers and land, once coal proved to be obsolete? Would they seek a new image? Hashima Island could turn into Mitsubishi’s testing ground for reinvention of the obsolete; inverting the relationship between architecture of extraction to one of production, giving life to the forgotten and unwanted.