A Bank in a Bank

Taylor Halamka (MArch I ’19), Julia Roberts (MArch I ’19)

A bank for Burbank demands a purposefully plain and solid structure to house its flimsy program. A bank for Burbank is a bank in a Bank; a Sullivanian structure reconstituted with dumbed-down materials, flickering between conception as model and construction as building.This is discovered by the driver, by the pedestrian, by the patron. This bank is a pile of anxieties over what a bank should be.

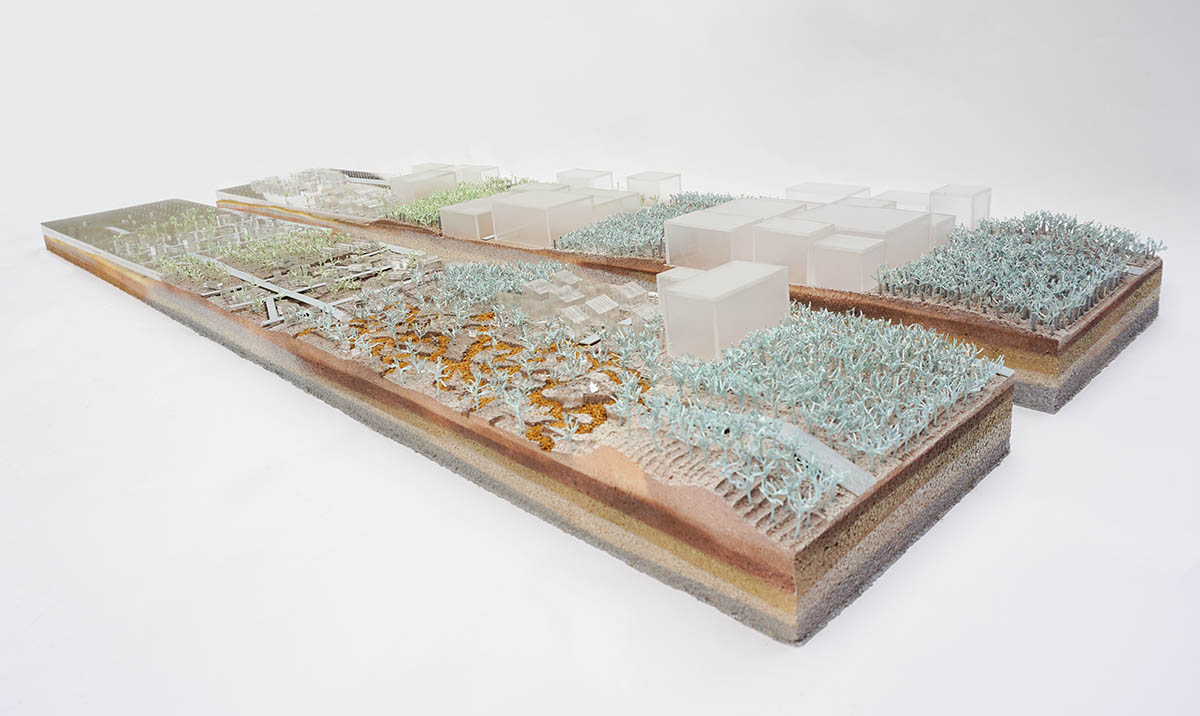

Stable/Unstable Grounds

Sarah Diamond (MLA I ’19), Wan Fung Lee (MLA I ’19), Matthew Macchietto (MLA I ’19)

Our project is an exploration of the relationships between materials, inorganic, organic, living and dead, of various longevities and their inherent levels of stability. The layering of materials and their various life-cycles yields a diverse and flexible urban fabric and allows us to reimagine the way a city is organized.

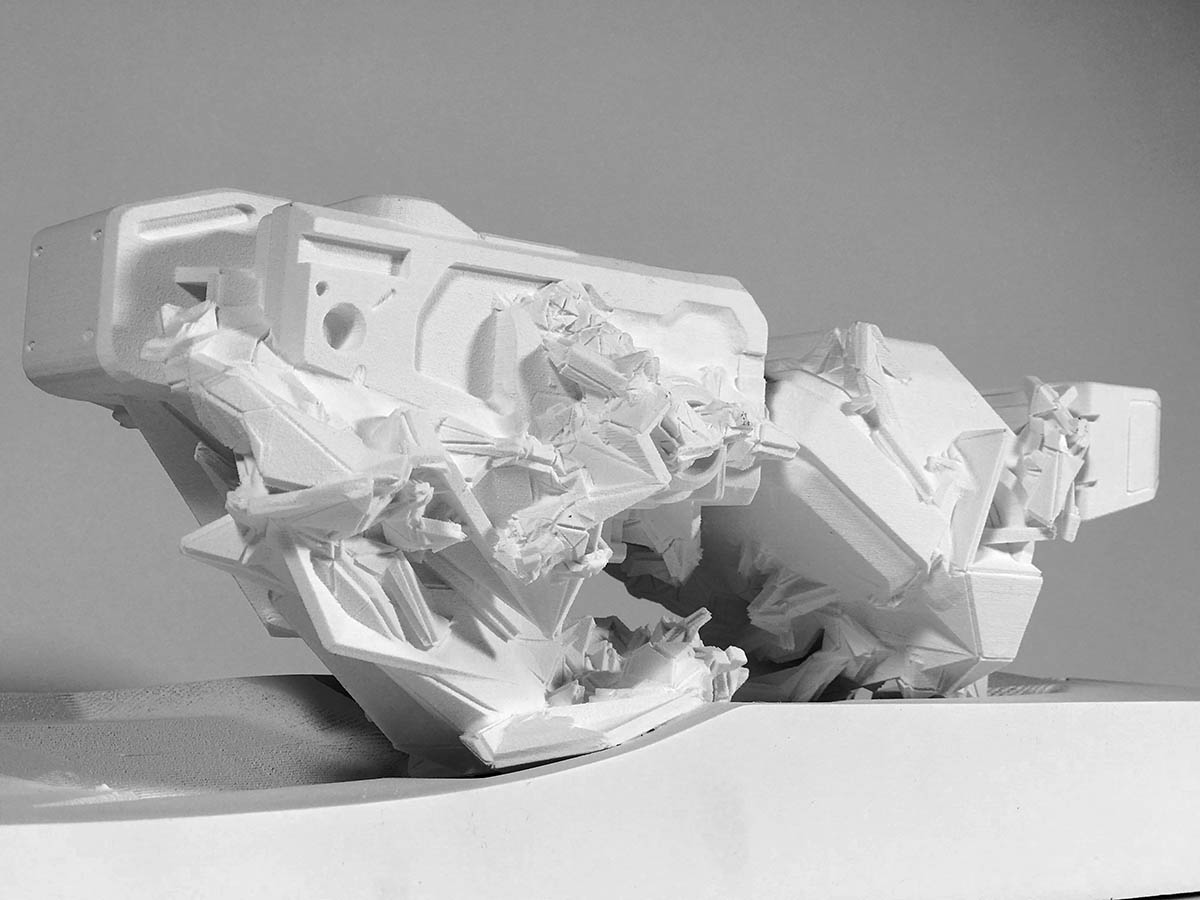

Tin Whiskers, or The Ghost in the Machine Part II

Matthew Gehm (MArch I ’19), Jonathan Gregurick (MArch I ’21)

Our project represents the culmination of exercises, developed throughout the Hybrid Formations course. Like “tin whiskers”, strange metallic growths which mysteriously appear on printed circuitry, this project imagines a machine order which is then altered, or corrupted through geometric, formal processes to create a new, hybrid whole. The machine is an entity in motion (the ceaseless turning of gears, belts, pulleys, or hydraulics) that becomes “trapped” or frozen by its own formal corruption: the introduction of an algorithm that builds new geometries from its existing verticies and faces in a seemingly chaotic, yet highly controlled mechanism. As “tin whiskers” preclude the inevitable, functional destruction of the machine, so too does the algorithm formally destruct – or de-construct – the machine, much like a geometric virus. The project is a conceptual hybrid of motion and stasis which blurs the lines between control and chaos, structure and fenestration, or machines and technics.

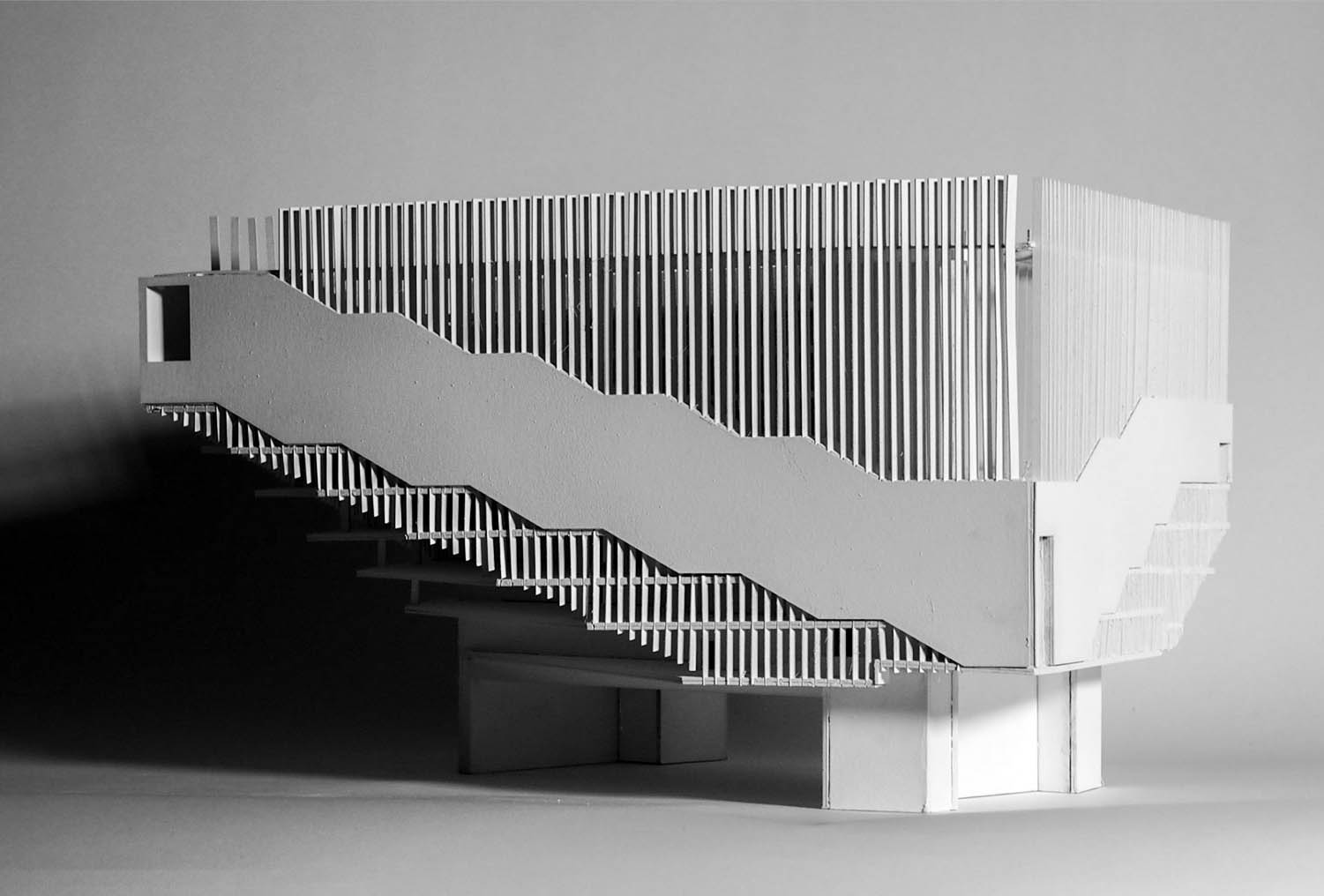

The Stair Core Theater

Alfred Chun Hin Pun (MArch I ’21)

The key concept of this proposal is grounded on circulation. The design aims to draw the vibrant urban flow and dissipate it over the building through four giant structural that wrap around a juxtaposed centralized theater. The collectively formed a loop spine that blends circulation with structure and programme, transitioning people from street level smoothly upwards step by step in a systematic and programme responsive manner.

Each contains two sets of stairs: The Open Stair and the Enclosed Stair. The open stairs collectively form a loop with access to natural sunlight serving as a semi-open Berklee campus while the enclosed stairs serve mainly for theater back of house purpose. Last but not least, the facade is designed to keep the clean reading of the building mass with angled structural frames extending from the staircores forming a subtle but distinguishable screening filter on all sides.

Center Stage

Adam Sherman (MArch I ’20)

Sited in Boston’s Back Bay, this performing arts center provides a new home for the conglomerate of the Boston Lyric Opera, Berklee College of Music, and Boston Conservatory. The program demands a flexible theater design, housing performances that range from small student productions to large operas. To accommodate the diverse needs in capacity, the building’s theater contains six pods—four raked and two flat—that connect to a central stage and fly tower. Acoustic wall panels can be raised and lowered in the fly tower, opening the stage up to a variety of configurations, from a small proscenium arrangement to a large theater in the round. This centripetal organization radiates throughout the entire building, which cantilevers over the Massachusetts Turnpike and assumes a distinct urban figure as a gateway to the city.

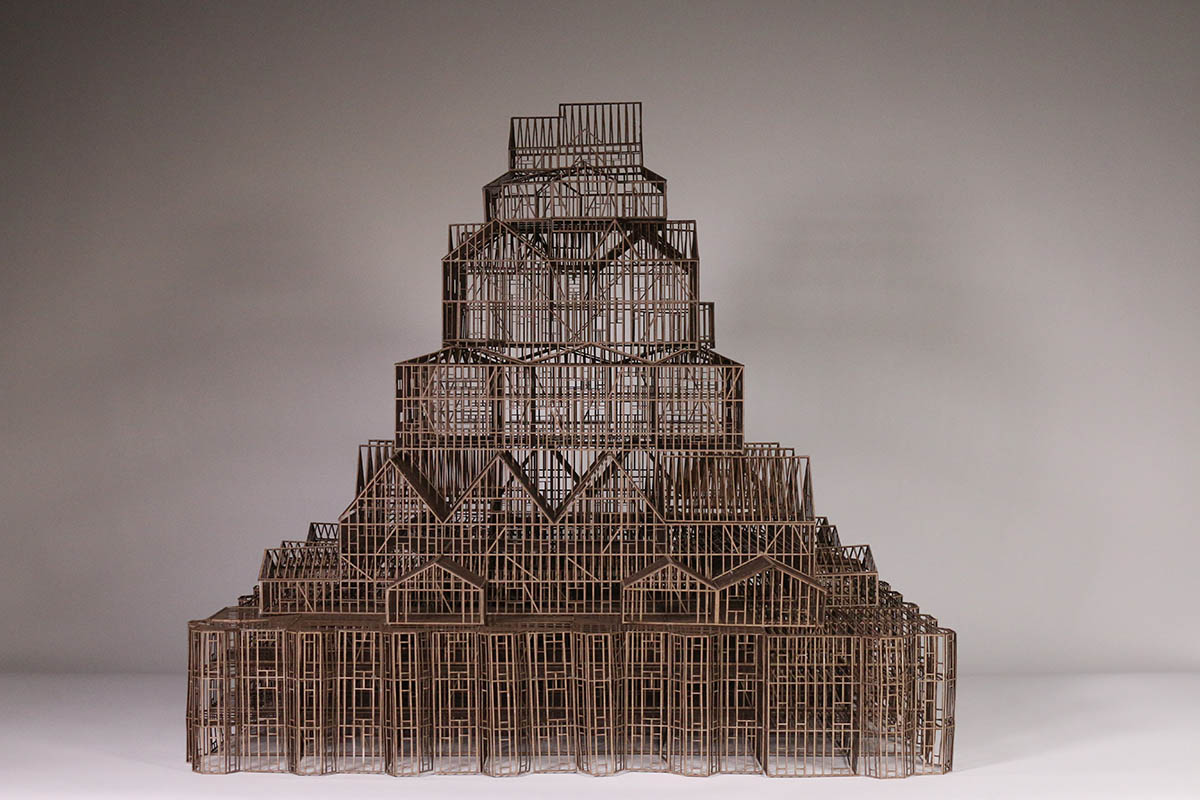

The Subprime Monument

Eduardo Martínez-Mediero Rubio (MArch I ’19)

The tower is organized by the layering of various 20th-century American housing typologies that exemplify the social and economic structures of their time while evidencing the linear evolution of the house, constantly changing after every crisis. The balloon frame is taken as the epitome of American hous- ing construction, utilizing its ephemeral aesthetic to address the fragility of an economic system that cannot again rely on the unstable foundation of the housing market.

Perceiving

Han Cheol Yi (MArch I ’20)

The continuous topic in this work-series is centrality embedded within landscape and its impact on the viewer. Centrality – as a synonym more closely associated with directionality, order and rigid geometry – is in every respect more prevalent in the built and human-made environment, as opposed to looseness and arbitrariness inherent in landscape. By applying centric arrangements to a natural pattern, a binary wherein the appeal of these representations lies is acquired and allegorical translations of subjective experiences are pursued to be materialized in an image. Cave-spaces are represented by crumpled paper imitating stone structures to create these spatial experiences. Eventually, and particularly, the gap and the hole resembling portals of caves are perceived by the impassive viewer.

Tibet Contemporary – Outside/In_Between

Morgan Starkey (MArch I ’19)

The unending cycle of death and rebirth, the “Wheel of Life”, is a fundamental assumption in Tibet. Referring to the the aimless wandering existence in the material world, this conception of time has become central to their traditional art and iconography where wrathful gods of “time” proliferate.

In the West, the most recognizable Tibetan text is the Bardo Thodol (Tibetan Book of the Dead) translating directly to “Liberation through Hearing in the Intermediate State”. Bardo, or the “in-between state”, refers to the liminal phase of existence between two lives on earth. While many schools of Buddhism reject this condition, it is central to Tibetan Buddhism. Appropriately, the Tibetans have focused on the “in-between” state of life as so much about their existence is found “in-between”. Sitting on the roof of the world at the collision of two continents, Tibet marked a flow of ideas and information exchanged between China and India forming an almost hybridic culture. In modern times they have had to negotiate their relationship between these two rising economic giants as their land has become the link in-between, where trade routes and and railways are being established.

Tibet itself is now in a transitional state between a traditional way of life and the intrusion of modernity. Philosophically, Tibet has almost opposed change and growth, absorbing any accumulation of knowledge as merely tacit wisdom back into a mundane cyclical existence waiting for the next incarnation. In this way, Tibet has existed outside of time, in a space in-between the mental and physical, between the real and the imaginary. Foucault may have called this Tibet a heterotopia of time, existing outside of time and insusceptible to its ravages, just as he describes museums and libraries in his 1967 essay, Of Other Spaces:

“Museums and libraries have become heterotopias in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit… By contrast, the idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity.”

Museums represent permanence, a crystallization of singular moments in history and humanity’s advances through the accumulation of knowledge. Simultaneously, they also represent cyclicality in that the reason we connect with the past is that we can read a timeless human condition into any artifact. Museums, like Tibet at large, serve as an in between state: between singular permanence and cyclicality.

With few proper Museums in Tibet, the region is due for more spaces of reflection that memorialize the unique experience of the Tibetan people. This contemporary museum and library of ancient scripts will be a place of exchange, where tourists learn about locals and vice versa. Where tourists are not only present to consume, but are encouraged to use the space to hold programs and seminars. Just as Tibet has served as the link between so many things in our world, this Museum/Library will serve as another type of link, between tradition and modernity, local and tourist, between permanence and impermanence, and most importantly between this life and the next.

Memory-Go-Round

Hanna Kim (MDes ’19), Eric Moed (MDes ’19), Andrew Connor Scheinman (MDes ’19), Malinda Seu (MDes ’19)

In August 2017, thousands of torch-bearing white nationalists descended on Charlottesville, Virginia to protest the planned removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. This intensified a national reckoning with the hundreds of Confederate statues that dot cities from Jacksonville to Helena, Montana, leaving a stockpile of removed Confederate statues with nowhere to go and Americans with questions about what to do with them. Should these monuments be destroyed, or relocated to museums or cemeteries?

The violence of militant protesters in Charlottesville and elsewhere loudly echoes the Civil War. Even today, Confederate and Union continue to battle in the American public sphere, a proxy war 150 years in the making. Still, Americans on both sides have more in common than they imagine: many Confederate and Union monuments are identical, produced at the same foundry with the same likeness.

As Robert E. Lee himself wrote, it is wiser “not to keep open thesores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelingsengendered.” Memorializing war heroes also memorializes war, and if the idea of a union is to be achieved without the proxy culture wars of today, monuments engendering these feelings—on either side—must be removed of their military valor. Civil War monuments must be trained for peace.

Enter the Memory-go-round, a monumental carousel that confronts Civil War revisionism by building on a different sort of American nostalgia.

Now known as a large-scale mechanical amusement ride, the carousel originated as a training game among 12th-century Arabian and Turkish warriors, named from the Spanish carosella, meaning “little battle.” In the Middle Ages, it developed into a festooned and flamboyant festival activity, for which warriors would practice on a device featuring legless wooden horses suspended from arms on a central rotating pole. Festival goers, enthralled by the public performance of these games, eventually took part, turning the carousel from a training game to an object of entertainment. Only after migrating to America near the turn of the 20th century did the carousel become the sizable, decorative ride we know today, adorned with regal ornamentation that mimics and expands upon the device’s militant past.

Civil War statues have uncertain futures and militant pasts, which must be remembered but no longer celebrated. To train them for peace, the Memory-go-round enlists these soldiers and their steeds to gallop side by side with their former enemies—to be, simply, American. Just as carousels evolved from military exercises to entertainment devices ringing in the new American century to the tune of carnival music, so too will Civil War monuments become monuments to more noble American ideals of this century—monuments to the devalorization of war, monuments toward playfulness and peace.

In its first incarnation on the National Mall, the Memory-go-round will contain several Confederate and Union monuments collected from all over the country. The Memory-go-round will travel throughout the American public sphere, inviting Americans to ride alongside Civil War veterans and atop their horses, and encouraging local monuments to join in on the fun. Cyclical and non-hierarchical, the Memory-go-round confuses North and South, refusing to take sides or even acknowledge differences between mounted Civil War generals and the children riding with them. As a monument to the removal of memorials from their pedestals, the Memory-go-round gives all Americans— Union or Confederate, past or contemporary—equal footing.

Flatbed

Phillip Denny (PhD)

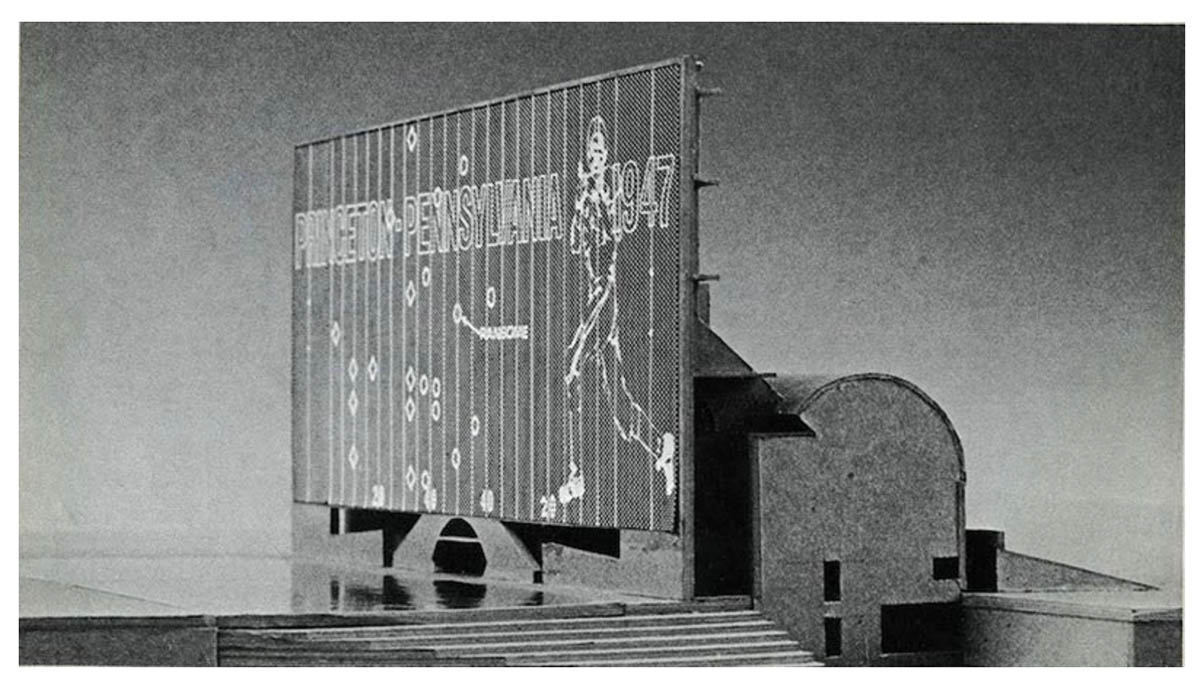

Art historian Leo Steinberg introduced the concept of the flatbed picture plane in a lecture given at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968; it was published in Artforum in 1972 and appeared in an anthology of Steinberg’s writing under the title Other Criteria.1 The “flatbed” refers to his assertion that the essential verticality of the picture plane in painting had recently been substituted for a fundamental horizontality, like that of a flatbed print- ing press. For Steinberg, the flatbed picture plane is “any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered, on which infor- mation may be received, printed, impressed—whether coherently or in confusion.” Importantly, Steinberg’s “flatbed” is an abstract substrate, but it is also an irreducibly material one, that is, some thing onto which “objects are scattered” or “data entered.” Steinberg’s principal example is Robert Rauschenberg, whose screen-printed collages and combines evince a play of data that reconfigures the pictorial surface as an abstract window of sorts. This picture plane attains dual status as both abstract and real, a surface that is at once existing in actuality and as a conceptual ideal, like a geomet- ric plane: a perfectly flat, featureless surface. Indeed, whereas Steinberg’s deployment of the term “plane” is sometimes passive (e.g., “a receptor”), it is elsewhere rendered active:

Rauschenberg’s picture plane had to become a surface to which anything reachable-thinkable would adhere. It had to be whatever a billboard or dashboard is, and everything a projection screen is, with further affinities for anything that is flat and worked over—palimpsest, canceled plate, printer’s proof, trial blank, chart, map, aerial view.

Any flat documentary surface that tabulates information is a relevant analogue of his picture plane—radically different from the transparent projection plane with its optical correspondence to man’s visual field.2

The inherent contradiction of the “flatbed picture plane” comes to the fore when Steinberg describes the “picture plane,” a geometrical product of linear perspective, as if it were a material thing. The “picture plane” was just an “imaginary plane corresponding to the surface of a picture” before Steinberg’s artists took hold of it, “to become a surface to which anything reachable-thinkable would adhere,” like pasting bills to a wall.3 This persistent contradiction suggests both the unresolved ontological status of the “picture plane” and the limited pliancy of the term as Steinberg resolved to stretch and to redefine it after 1968. But this ambiguous linguistic terrain arguably held the greatest import for architecture, and indeed, the question of “whatever a bill- board or dashboard is” was also on the minds of Steven Izenour, Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and the Yale students they’d brought to Las Vegas that same year. Their task was twofold: an “open-minded and nonjudgmental investigation” of the strip and the invention of new graphic techniques to document it.4 Their now-famous charts, diagrams, and collages of Las Vegas’s abundant billboards, its neon signs, and “every written word seen from the road” suggest that some architects already had the flatbed in hand.

1 Leo Steinberg, “Other Criteria: The Flatbed Picture Plane,” in Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972).

2 Ibid., 88.

3 This definition of “picture plane” is taken from my nearest “reachable-thinkable” dictionary; see “picture plane” in New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd ed., 2017).

4 See Steven Izenour, Denise Scott Brown, and Robert Venturi, “Syllabus, Learning From Las Vegas Studio, Fall 1968,” Yale School of Architecture, 1968. The first edition of Learning from Las Vegas was published in 1972 and a revised edition was issued in 1977.