Maison Héroine

Tasos Giannakopoulos (MArch II ’19)

A future has arrived. The year is 2048 and automation has resolved all of issues of labor on behalf of humans. Time is abundant. Spaces designated for work have become obsolete. Metropoles and their concomitant working opportunities have become irrelevant. A massive flee towards the countryside is evident. Housing is urgent. How does one live when there is no work to be done? How does architecture respond to such a crisis?

The time of the engineer is a faraway echo in 2048. The time of the poet has arrived. People do what they have always been doing when labour was being taken care of; they philosophize, they make art and have sex. Architecture is the medium though which the desire for free, unconstrained creation from every institution and authority is fulfilled. A superblock of nine housing units each arranged around a central garden is the prototype that is proposed. Public rooms with functions that constitute the everyday rituals of this new reality fill the ground floor in various arrangements. One occupies rooms instead of apartments scattered around the blocks in the way that fits their own personal lifestyle. An excessively stimulating urban environment is created. The linear narrative is no longer available. The spatial hyperlink has been fulfilled. Forms from the heroic Modernist age are appropriated shamelessly. La Tourette is mass produced and calls forth these new followers to match their spaces of dwelling with their way of living.

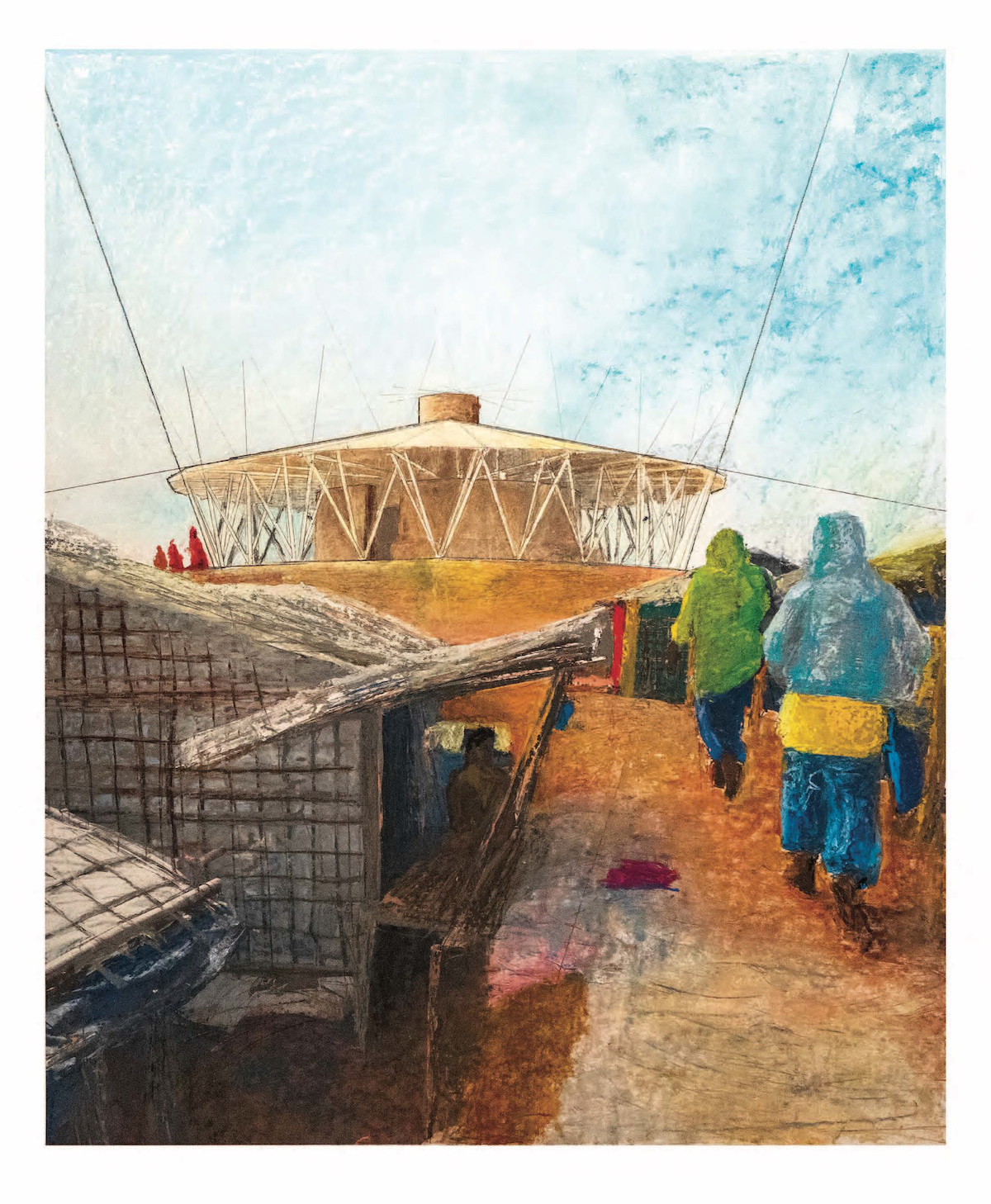

Living is Form

John Wagner (MArch II ’19)

Among the extents of international human aid facilitated by the United Nations High Council on Refugees and the International Organization for Migration, intervention strategies are characterized by utilitarian means, and a stark semblance of society, expression is supplanted by mere sustenance. Could instead an artistic or architectural intervention engage residents of this camp, who endure an indeterminate duration of temporary occupation, in a constructive conversation of how space and form could be organized to meaningfully counteract their experience of a suspended state of dwelling? Could the installation itself become a method of healing of traumatic experience? As an ephemeral construction, could the event of its installation serve as a memory vessel, demarcating a moment at the outset of an indeterminate future timeline, formulating the core of new spaces of solidarity?

While directly addressing the corporal needs of refugees, may this intervention also itself be a process by which primary trauma may be comforted and ongoing traumas of camp be mitigated? Can the art intervention, in form and in process of conception, be itself both a memory device, a symbolic device, and a therapeutic device? With reference to the conceptual provocation Brian Holmes identifies in Eventwork, social movements “are vehicles to change the forms in which we are living.” Within the exceptional circumstance of the camp, can a design intervention to address an essential need itself be a vehicle to change the condition of subsiding within the camp?

Adopting the position that art and architecture can expand beyond the object, the argument of the intervening project Living is Form seeks to reveal how a process of creating and shading a public space could be means to enable and empower a community to conceive, organize, implement and maintain their own environment.

Taking the form of three urgent need areas, Living is Form materializes as an improvisational sunshade for delineating public space, a prototypical community kitchen for engendering third spaces in camp neighborhoods, and a street trellis that serves as a platform for agricultural nursery, provisional sunshade, and readily appropriated framework for privacy screens.

Each of the designs is intended as a pattern, script, or readily appropriated building form that enables residents to create, augment, or appropriate spaces within the camp. The method of implementation is through community engagement and outreach, a new conception of space within the camp may be realized. The physical spaces delineated by these object(s) of intervention become a focal point around which new social configurations and realities can condensate, engendering a new condition of empowerment of the refugee.

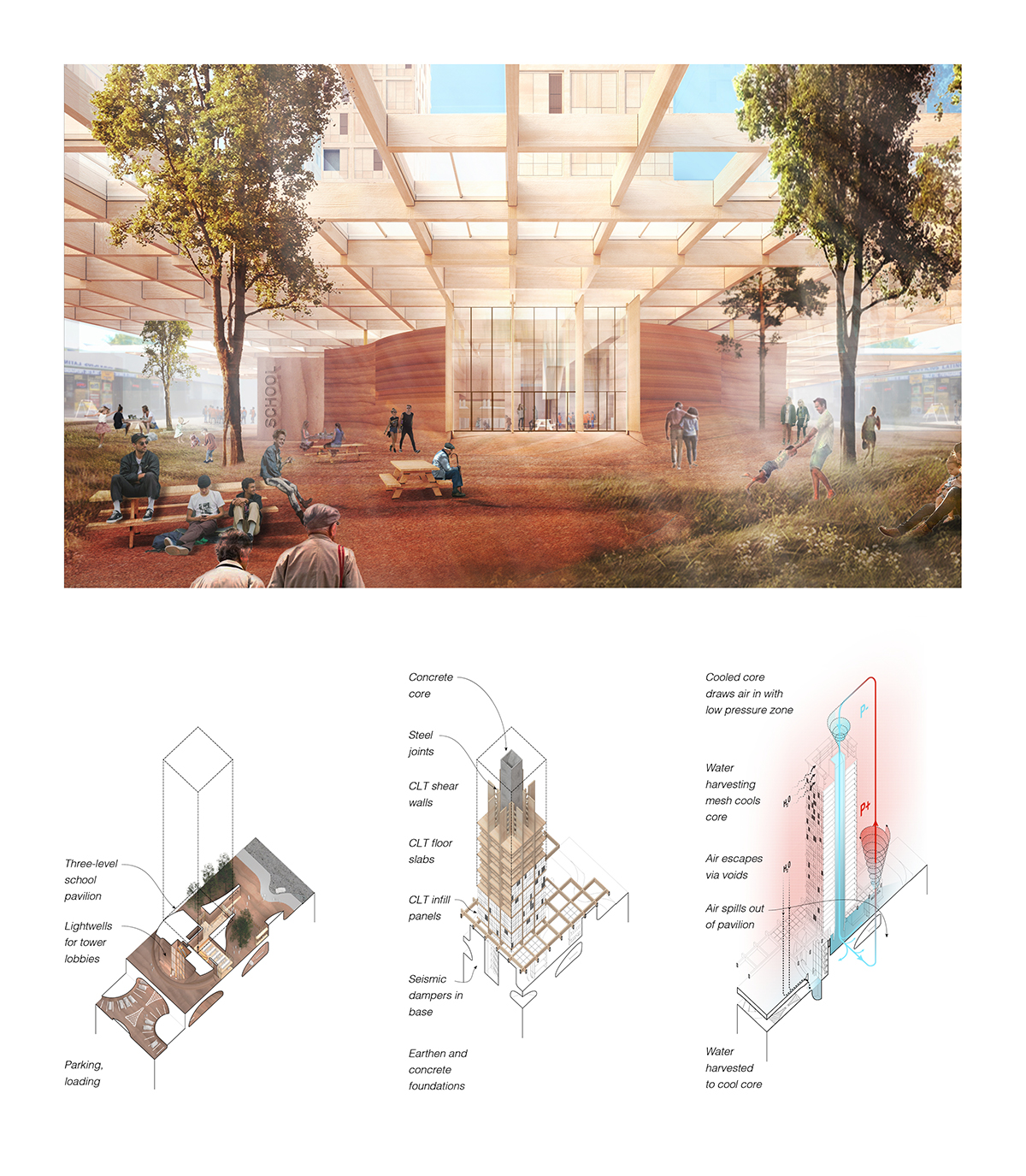

Carbon Park, LA

Augustinas Indrasius (MDes ’19), Peteris Lazovskis (MArch I ’20), and Thomas Schaperkotter (MArch I ’20)

Carbon Park, LA reimagines how real estate investment may fuel social benefit and ecological sustainability by connecting private investment with public space to seek balance for investors, the downtown Los Angeles community, and California’s growing carbon economy.

Metro Strand: Renewed Vitality for Overtown in an Urbanizing Miami

Sam Adkisson (MAUD ’19) and Hiroki Kawashima (MAUD ’19)

Metro Strand: Renewed Vitality for Overtown in an Urbanizing Miami proposes a smarter way for Miami’s continued urbanization, with the added complexity of climate change, to establish a better method for future inner-city growth for the impoverished community of Overtown.

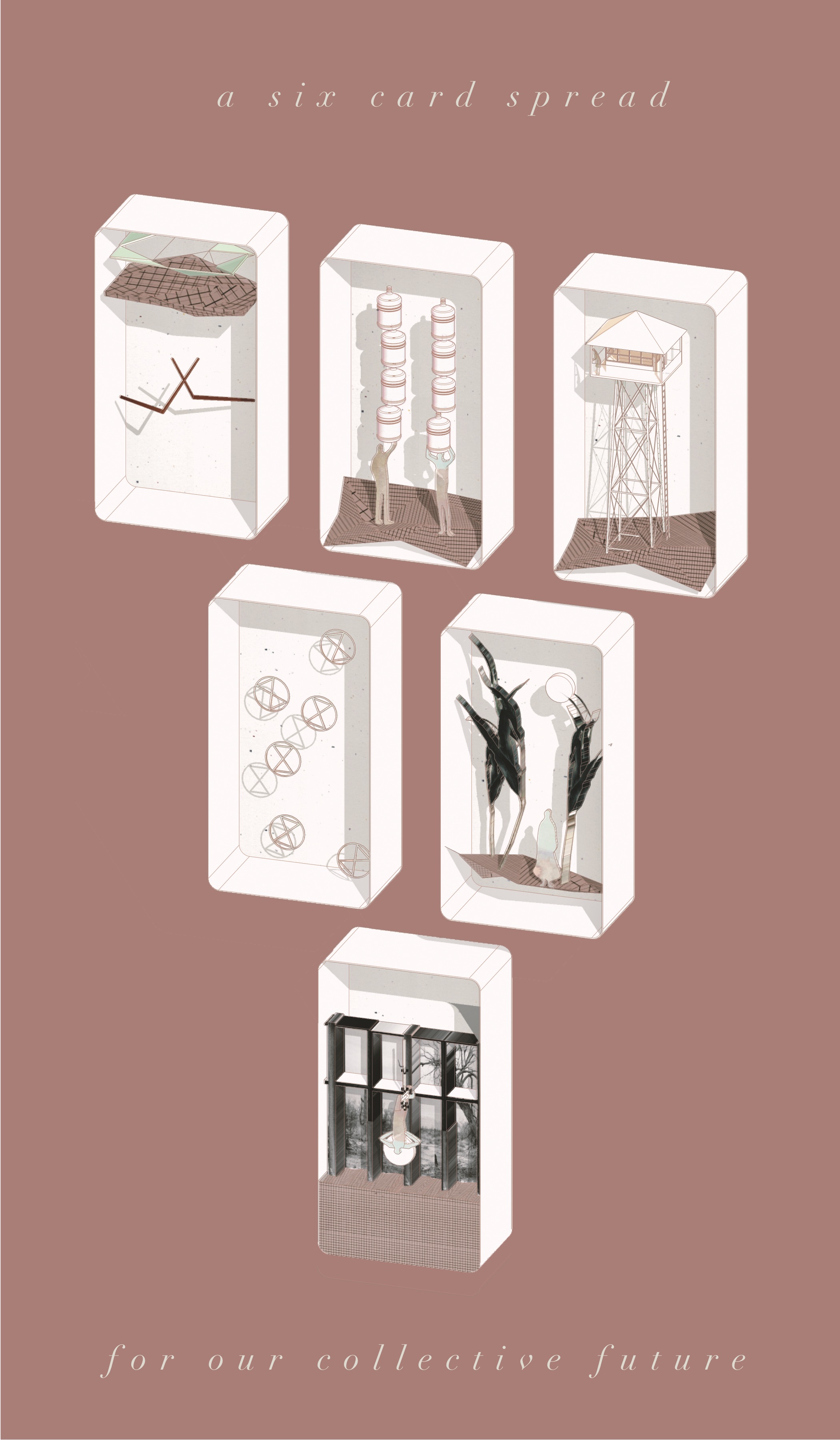

The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic: an Adaption with Projections on a New Climate

Tessa Crespo (MDes ’20)

As an experimental infrastructure, I reimagined the classic archetypes of tarot as a means to reconstitute the human condition and our perceptions of boundary and territory. This required a reexamination of our understanding of being as well as challenging the constructed myths of scarcity and abundance that justify violence towards both human and non-human entities in modern societies. For this project, I reinterpreted a six card spread for our collective climate, where we can look to tarot not as a fortune telling device, but rather a conduit between unconsciousness and consciousness. I believe that alternative modes of representation could empower the disenfranchised and lead towards new forms of legitimacy. Acknowledging that neither frameworks nor facts are static, but rather are continuously being reconstituted, may lead to a form of representation that is more event based than object based. Understanding symbols, such as the border wall, as a phenomenon instead of an object will help us think outside of the constraints of geographic space to speculate on alternative realities or ways of seeing. Experiences constitute our understanding of the world, yet many of the hard sciences avoid the experiential as a legitimate form of knowledge. For this project, I was interested in the idea of tarot as an alternative technocratic device that subverts orthodox projection methods and how a more empathic form of representation could make visible the links between climate change, resource scarcity, and migration.The Hidden Room Elevation

Diandra Rendradjaja (MArch I ’22)

The elevation of this architecture conceals not only the dynamic sectional quality of the interior but also the perceptual discrepancies created through forced perspective manipulation that produces a defamiliarization through scale. Throughout the project, perceptual scale distortion happens mostly in interior framed views while the facade remains static and mute. This representational experimentation investigates the elevation drawing as an instrument to reverse this reading of perceptual scale distortion from an interior depth in the longitudinal orientation to an elevational depth in the transversal orientation.

Taking the elevation of the “normal” room as the stable and ideal scale and projecting it to the other altered rooms produces a new set of elevation that begins to reveal depth as some room appears larger or smaller than the others. This is then re-interpreted as a new form of architecture where each room is an independent volume that intersects three-dimensionally with one another. In contrast with the original architecture, the new architecture expands to a thicker form towards the transversal direction that disrupts the single longitudinal reading of the existing.

Common Shallows

Samuel Gilbert (MLA I ’20), Shira Grosman (MLA I ’20), and Yujue Wang (MLA I ’20)

“Common Shallows” transforms the area of the South Bay into a new type of public space that embraces the shallowness of water as a means of connecting communities and bringing populations together.

The history of Boston can be interpreted through a series of population introductions, land reclamation projects, and ecological degradation. In this project, we are looking at how these three factors have been intertwined for at least 300 years. Specifically, we looked at the trajectory of the African-American population, the Irish population, and the disappearance of shallow water ecotopes in Boston Harbor. We have tracked the migrations, settlements, and displacements of these populations against the steady infill efforts and land reclamation projects in Boston. By tracing these processes in parallel, we have revealed the South Bay as a central knuckle, physically separating these communities.

We divide our site into 7 reserves. The whole is bounded by infrastructures, sea level rise and lack of residential. Since there is a mixture of many public agencies, like MBTA, and some private properties, it’s easier to extend the site into a public entity. Within the site, different reserves are bounded by infrastructures and material conditions. The reserves are defined by the existing material conditions, deconstructed into gravel, substrate and boulders. The surrounding waterfront area will be affected and activated, creating a new coastal edge. The reserves consist of a multitude of shallow water bodies with a new edge, shifting disparate community centers toward one another in a common direction. We have compiled the Shallow Water Anthology (book) to demonstrate the range of conditions and experiences provided for throughout the reserves. Dynamic nature of the tidal range creates a multitude of opportunities for different experiences. The Anthology chronicles the moments of shallowness throughout the day and as conditions change over the next 100 years. Reframing neighborhoods connection to SLR and in so doing, establishing new connections between populations. Shallow water as accessible form of interaction with the ocean

Becoming the projector: an ETUDE for class PUBLIC PROJECTION

Lins Derry (MDes Tech ’20), Delaram Rahim (MDes ADPD ’20), and Iris Xia (MDes ADPD ’20), with support from Krzysztof Wodiczko and Shining Sun

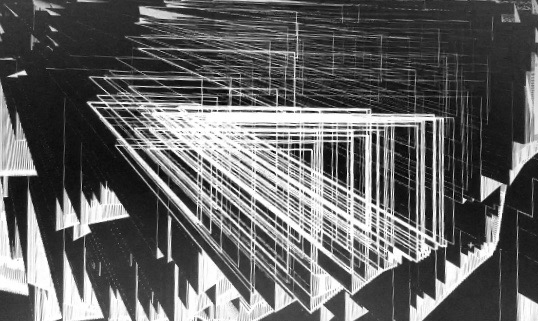

This project is a study of the body becoming a projector by movement in space. Approaching the project as research, we experimented with the improvised relationships between the code, movement, music, and the interactive relationship. The technology captured the movement of the body and left a trail of lines, shapes and shadows in the space, creating the architecture that was generated through the movement while also creating a feedback for the movement.

In terms of the choreographic design, the work begins with a landscape projection made by the same Particle Class connected to the motion. This landscape becomes a frame for the body as well as an information display for the audience to begin decoding. The performer moves slowly, matching the geometric forms in the landscape as well as those that her motion generates. The music starts with ambient sounds that are non-melodic that correlate with the abstract geometry that the projector creates

As the music shifts to a more rhythmical score, it energizes the body to respond to the projection more rapidly and the movements become more organic. The conversation between the projector and the body is switched in which the geometry is following the performer’s choices and movements manually. In this way, the performance becomes a trio with each element a powerful entity. The triangular shapes produced by the Particle Array abstractly trace the movement and leave a trail, like a musical echo in space. This etude was an experimentation of this ‘trio’ becoming the projector as it projects sound, movement and space.

Sound by Pomassl – Atenna Atoll, Opto – Opt File 1.

INTRODUCING GIM: Geographic Information Machine

Isabel Preciado (MLA I ’19), Annie H. Lynch (MLA I ’19), and Sarah Diamond (MLA I ’19)

The production of contemporary cartographic imagery relies on GIS software, a powerful yet at times limited tool. We propose a new, analog machine, one that re-projects analyzed data onto a three-dimensional surface and develops a new two-dimensional representation base on the proximity and, potentially, movement of light. In this first iteration, we have milled three topographic base options. By representing information through elevation, we control distance from surface to light.

The topographic models represent the following:

- The number of logged “thinking” moments within 50’ x 50’ squares.

- The relative pace of physical activity

- Value exchanged for goods and services

These topos sit within a frame suspending up to seven layers of information at a time. By etching, cutting, and sanding acrylic sheets we determine where and how much light can filter down to the topography below. The sun, or a UV light suspended above the wooden frame, shines through the filters onto a cyanotype treated sheet of fabric, draped to conform to the topographic model. The shadows creates by the filters develop an image on the fabric. After development, the sheet is removed, washed, and hung up, creating a new two-dimensional representation.

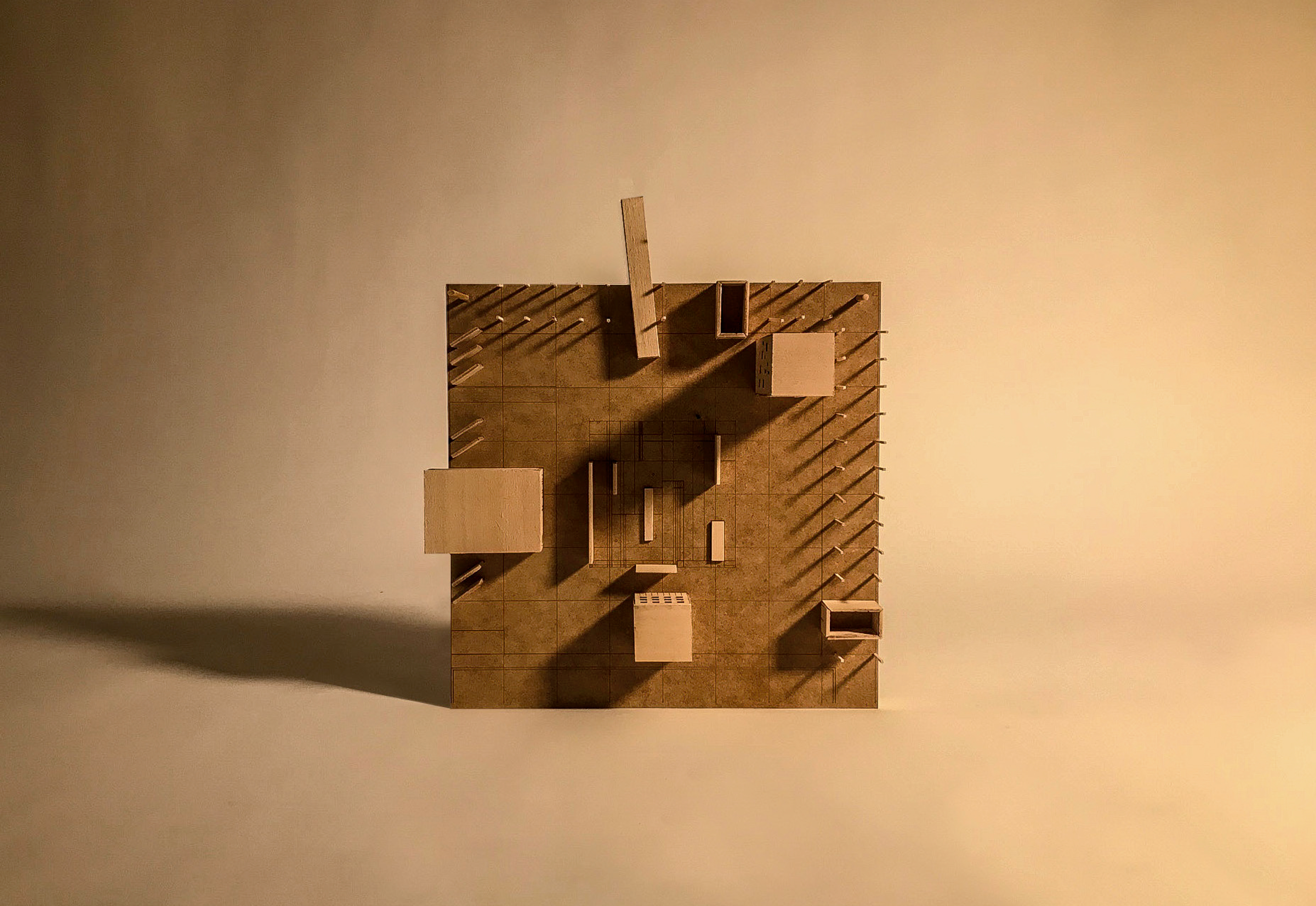

Empty House

David Kim (MArch II ’20)

Think of visiting an empty house that you want to live in.

You would enter through the front door and probably see a living room. Maybe a kitchen is close by, followed by a series of private bedrooms and closets. In the closet, you would imagine your clothes inside. In the bedroom, a new bed frame, your existing bookshelf, and a desk. In the hallway, you would like to hang your favorite art piece, or if you had bad taste, hang a knock-off VAN GOGH with a silver IKEA frame. At the kitchen, your dining table, and in the living room maybe a new TV with your grandma’s hand-me-down “L” shaped sofa. If you are a filmmaker, where would you put your film equipment? If you are a musician, where would you put your guitar and drums? You can imagine it all as it is an empty house. Your objects are what will make this your home. The architecture is set and you can imagine yourself and your things in it.

BUT, what happens if you flip this mentality around? What if your possessions were in front of you, there were no defined spaces like “kitchen” or “bedroom” and instead you imagined the architecture? After all, are not these constructs created by someone else? What are the spaces that would come out of this thought? Now, you think, my clothes do not necessarily need to go into the closet, my bed does not need to be in the bedroom alongside a nightstand and lamp. By inverting the object and architecture relationship, not only does this liberate itself from the idea of traditional domesticity, but it also allows you to rethink the definition of any given space.

Domestic space can now be defined by the objects, not by the architecture.