Community Equity Fund

Laura Lopez (MUP ’19), Daniel Padilla (MUP ’19), Eduardo Pelaez (MDes ’19)

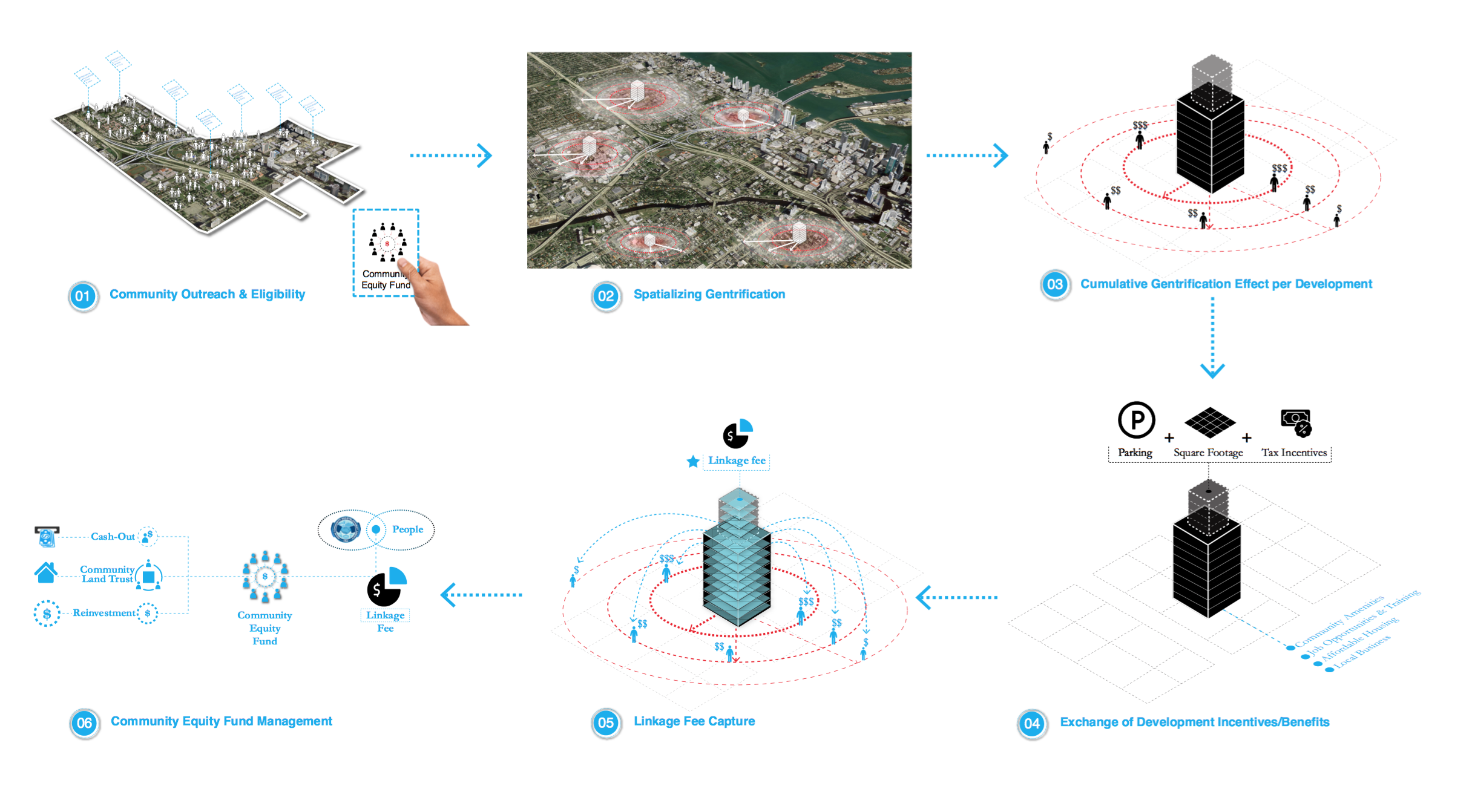

Due to its central location, Overtown, Miami’s oldest historically black neighborhood, is in the crosshairs of encroaching real estate development, and with it, impending gentrification and displacement. Gentrification, at its core, points at an imbalance of power between private actors and communities, where the private developers have the ability to dictate what the “highest and best use” is for a space at the expense of people who do not have the legal or financial recourse to dictate their own visions for the future of their communities. Our hypothesis is that long term economic resiliency is vital to curb the effects gentrification and that building equity is akin to creating agency to decide on the future of a community. With this in mind, we devised a development strategy that would transform today’s exclusionary development threats into opportunities for future equity building for Overtown residents. A Community Equity Fund is a collectively-managed, collectively-owned equity fund created through the capture of real estate development profits with the purpose of mitigating the effects of gentrification by providing access to capital to residents affected by escalating land values. It is a redistributive financial mechanism that would allow planning bodies or redevelopment agencies to provide building incentives to developers, in the form of additional square footage, in exchange for a share of the profits, which will, in turn, be pooled into a Community Equity Fund. This fund will be distributed among community members living on properties whose values will be directly affected by incoming development projects.

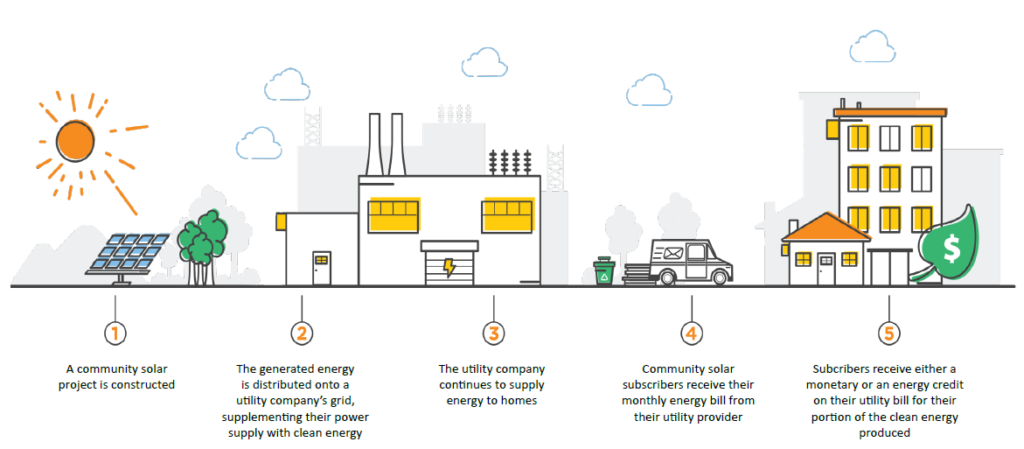

emPOWER Overtown

Catherine McCandless (MUP ’19) and Naomi Woods (MDes ’19)

Our project proposes a comprehensive solution to some of Overtown, Miami’s most pressing challenges relating to the impacts of climate change. This solution involves the construction of either a single community solar array or a series of community solar installations in or near Overtown that would allow for low-income residents to subscribe to the system and receive energy credits on their monthly utility bill.

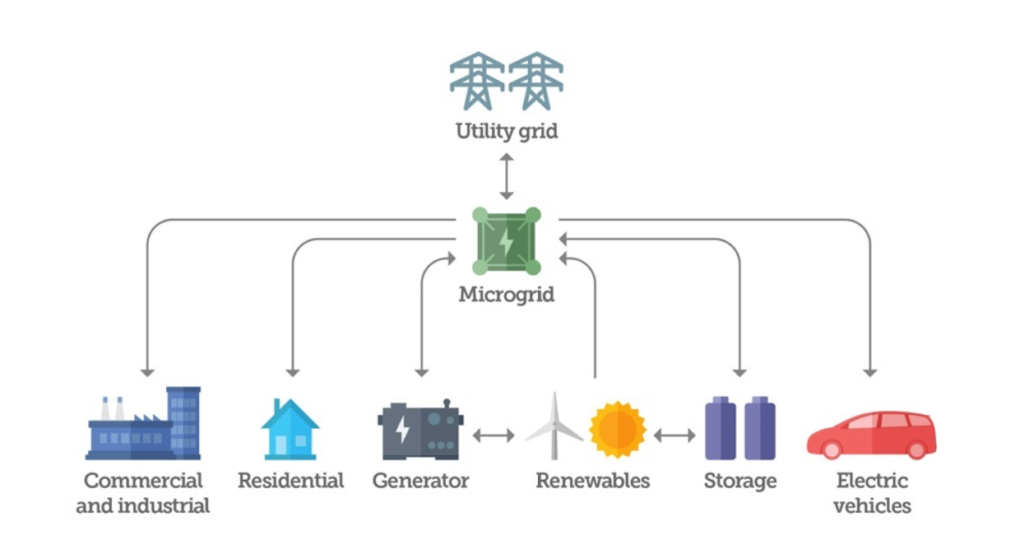

The community solar array would be connected to a microgrid to allow for resilient back-up electricity, which is crucial given that intense hurricanes will become more frequent as a result of climate change and low-income communities are often the last to have their power restored.

Additionally, the project would address rising temperatures in Miami and the consequent increase in electricity costs in Overtown; provide access to clean energy for Overtown residents; increase resilience of energy infrastructure for the general welfare of Overtown residents; promote community stability in Overtown through affordable and reliable energy; and empower Overtown residents through workforce development opportunities in solar.

This project is made possible through support from The Knight Foundation.

Democratizing Tech: A Co-Operative for Overtown, Miami

Sidra Fatima (MUP ’19) and Stefano Trevisan (MUP ’19)

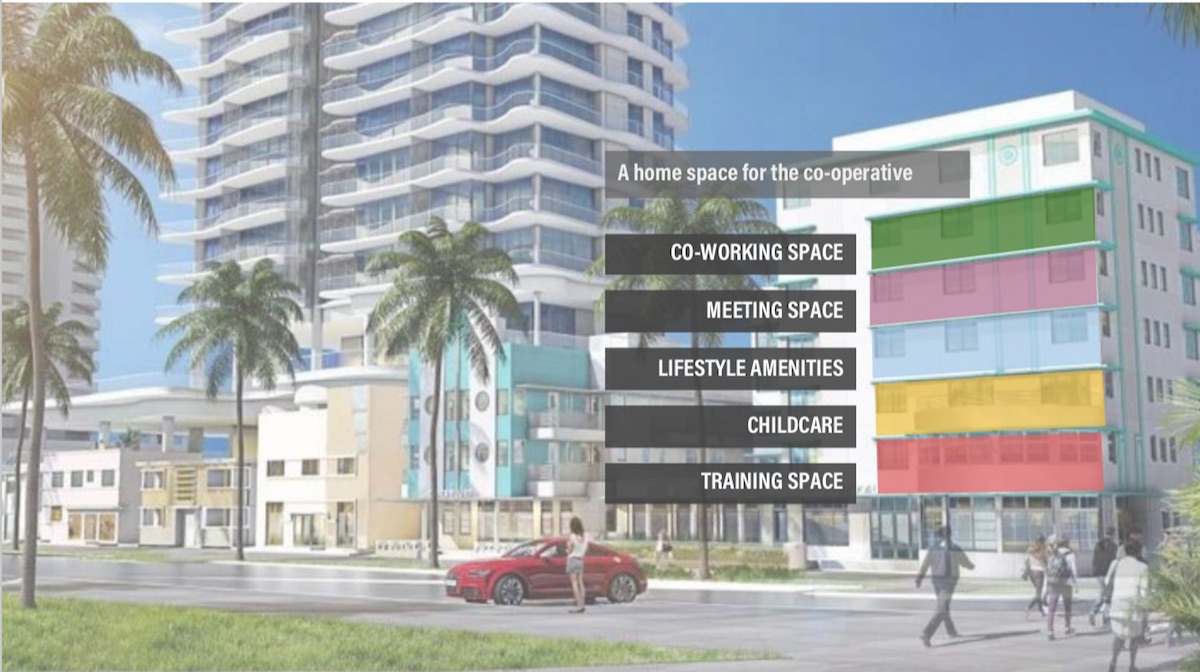

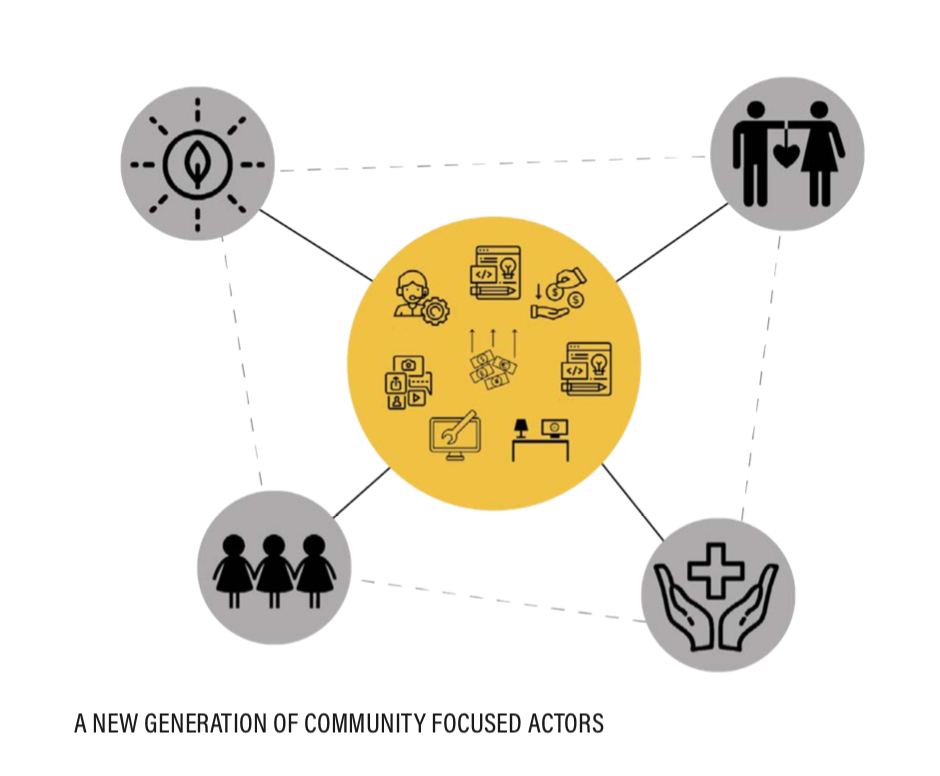

Our project explored the all-too-familiar narrative of how modern cities grapple with the complex evolution of economies and work patterns in an increasingly tech-centric world. We sought to shift the narrative from one of a ‘vulnerable’ community threatened by big tech to one of two actors mutually benefitting and growing inclusively, taking advantage of the unique qualities each has to offer. Toward this end, we proposed a co-operative that would subvert the typical pattern of gentrification by supporting the empowerment of residents and local entrepreneurs.

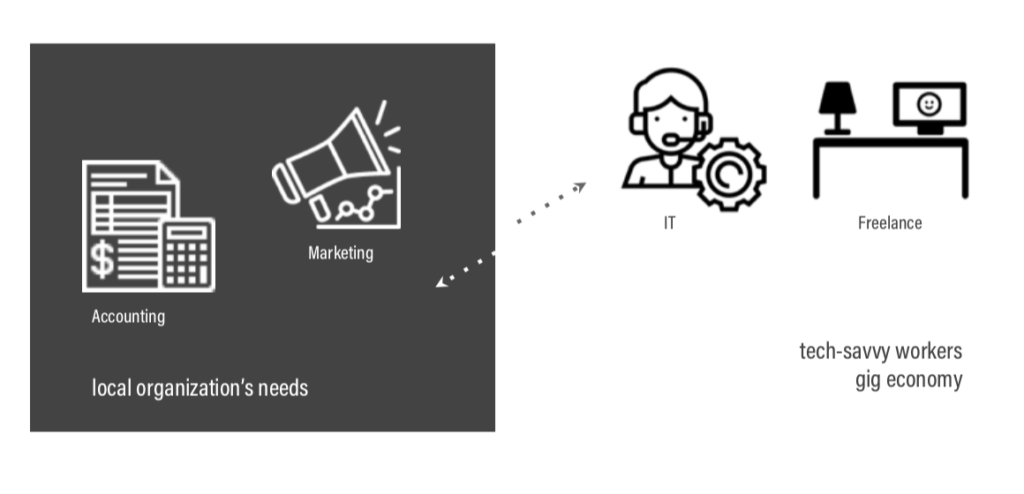

This project explores the potential of a co-operative that would link tech workers in the ‘gig’ economy to local organizations’ needs. By providing critical support services, these workers fill a necessary gap; by creating a collective that supports wealth creation, co-op workers can benefit from efficiencies of scale and their proximity to a booming tech scene. By housing the array of services these gig economy workers provide, as well as the workers themselves, we can create a one-stop-shop for all the organizational needs described previously. The goal is to provide the list of gap services these organizations face while creating an environment for Overtown residents to learn new skills and develop career pathways. This group can be incubated by competing first in their own backyard, contracting to provide services to key anchors in the community, then broadening their scope to compete in the open market.

Climate 2050 Justice Divestment Project

Sam Matthew (MDes ’18)

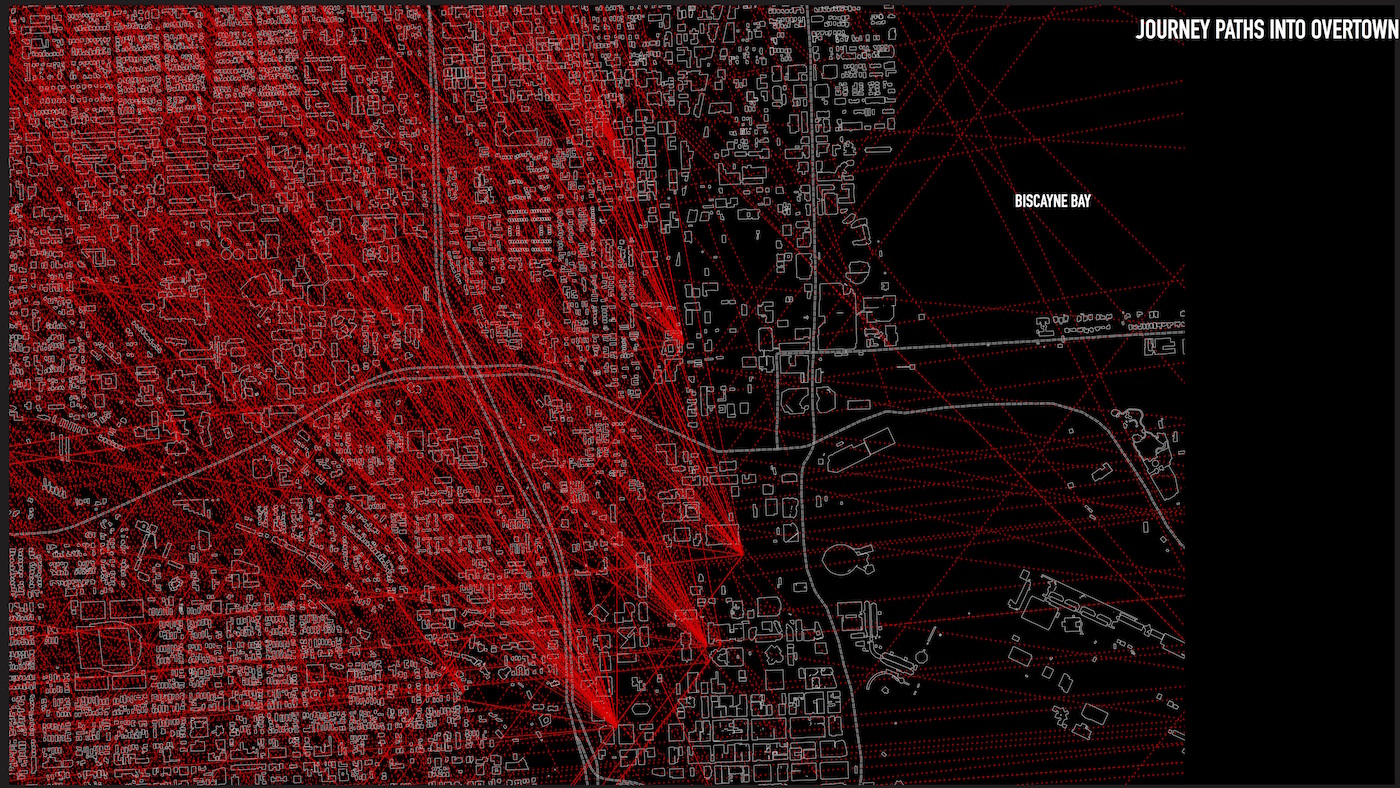

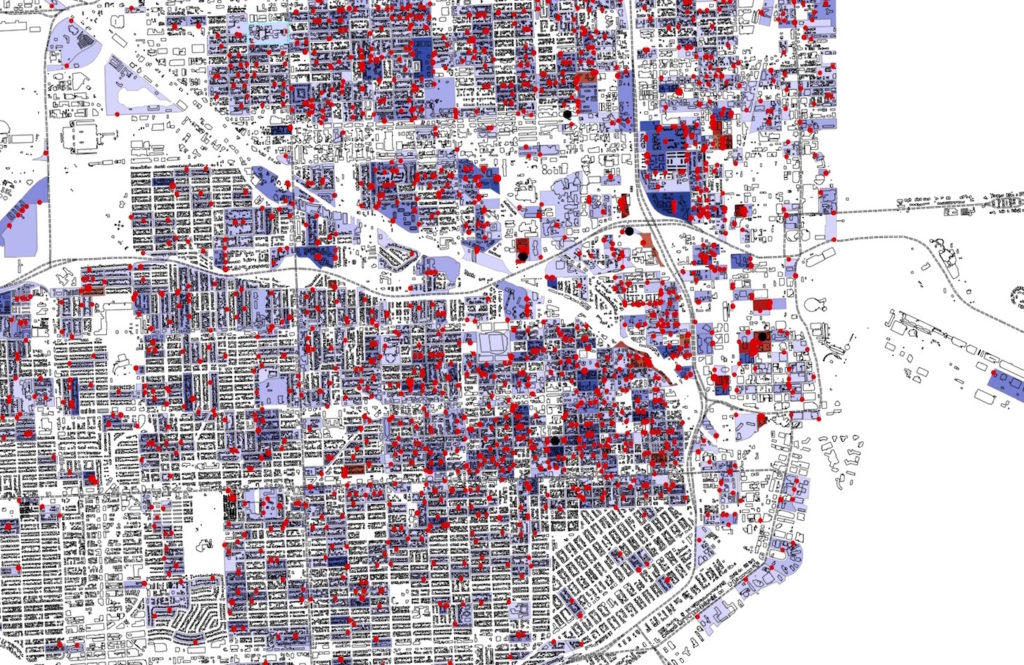

Inspired by the Million Dollar Block project, this project uses publicly available data from the Florida Department of Corrections, to map i) the address of every person released from prison into Miami Dade since 1999, and ii) the amount of money the state has spent to incarcerate each individual.

The maps reveal profound social and racial inequalities in Miami. The state has spent millions of dollars incarcerating people who return to the poorest communities in the city. In Overtown, a predominantly African American neighborhood, Florida has “invested” over 10 million dollars incarcerating individuals who live within a single block.

It also reveals how concerns about criminal justice and inequality exacerbate the threat of climate change. To resist these dangers, the project advocates for a strategy of Retreat, Protect and Reinvest:

Retreat: not only is mass incarceration detrimental to Miami, but Miami is detrimental to mass incarceration. Seven prisons and detention centers in Miami Dade County are likely to flood thanks to sea level rise, providing an opportunity to close facilities.

Protect: inclusive planning provisions for existing homeless shelters, half way housing and affordable housing is required to protect high ground sites with high numbers of formerly incarcerated people from “climate gentrification.”

Reinvest: a restorative justice policy would involved a spatial policy heavily in community networks, faith groups, restorative justice courts, transformative justice programs and alternative sentencing programs.

The Vulnerability of Potable Water with Climate Change in Miami-Dade

Pamela Cabrera (MDes ’19)

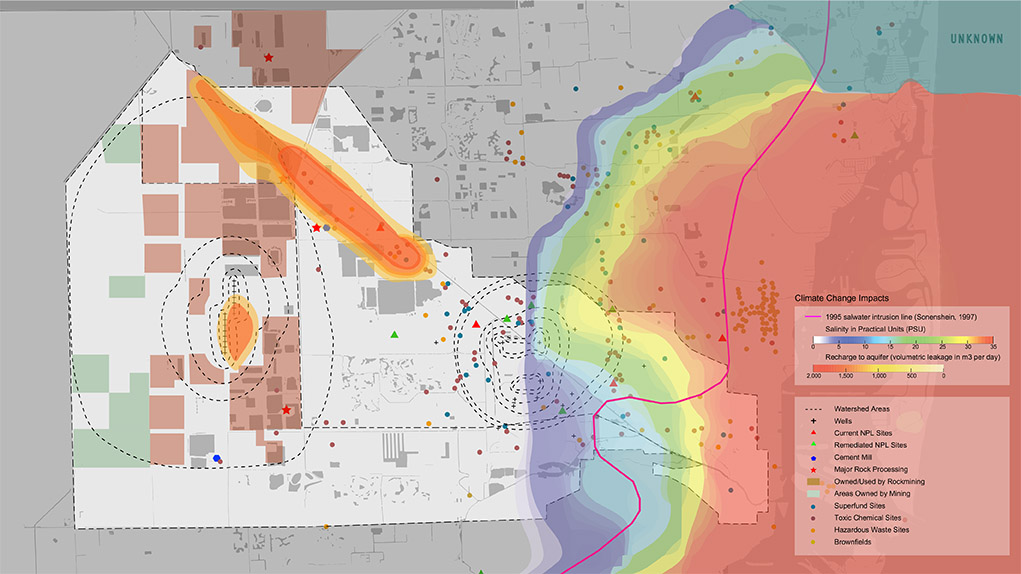

The environmental exposure to Miami’s drinking water, once mitigated with wellfield protection areas, should be reassessed to be resilient to future climate scenarios. Climate change has increased the vulnerability of potable water by blurring the lines of the wellfields with the imminent risks of saltwater intrusion and surface runoff water pollution from flooding. The adaptation of Miami-Dade to climate change will depend on the resiliency of its drinking water, and therefore of its aquifer. Three recommendations are presented in this work to achieve a more resilient aquifer: the re-evaluation and strategic enforcement of wellfield protection areas, a comprehensive implementation of urban strategies for water retention and reuse, and finally, to prioritize potable water resilience over other adaptation measures that jeopardize the aquifer’s health.

Miami’s potable water relies entirely on the Biscayne Aquifer, which is superficial, unconfined and has exceptionally high transmissivity. The aquifer is continuously recharged from rain and surface water through the ground but mainly through the hundreds of canals and pools that are used to drain the natural swamp of Miami. The county’s primary threat from climate change is the excess of water from sea level rise and increasing precipitation. Warmer temperatures are expanding the volume of the sea and causing sea level rise, which in turn reduces the groundwater storage capacity. There will be more water pouring from the sky and less ability to drain it to the sea or store it in the ground. Flooding will occur well before sea level rises above the land, and with flooding, and water pooling, surface contaminants will become a higher risk to the Biscayne Aquifer.

Miami-Dade’s potable water system is highly vulnerable to these events as it depends entirely on underground water that is currently at risk of pollution from surface contaminants and saltwater intrusion. Now, 97.5% of all drinking water distributed to Miami-Dade’s population above SW 8th St., including the city of Miami and Miami-Beach, is sourced from two wellfield sites: the Hialeah-Preston Miami Springs Wellfield and the Northwest Wellfield in the Lake Belt mining region of the county. Florida declared these sites wellfield in 1981 after the EPA revealed that approximately 90% of the wells had traces of industrial contaminants due to a lack of regulations. Today these wellfields have a fragile equilibrium with all the surrounding risks of contamination that have crept into their boundaries over the years. There are multiple risks of contamination within each of these wellfield zones including vicinity to the largest mining extraction region in South Florida and numerous Superfund and active National Priority List (NPL) sites. This work highlights the vulnerability of the shallow aquifer to surface and underground industrial contaminants due to climate change stresses. The resiliency of Miami-Dade county depends on access to drinking water, and therefore the county should re-evaluate and enforce new wellfield protection areas, incorporate new strategies for water retention and reuse, and prioritize potable water resilience over other adaptation measures that jeopardize the Biscayne Aquifer’s health.

Read about this project in Bloomberg Businessweek .

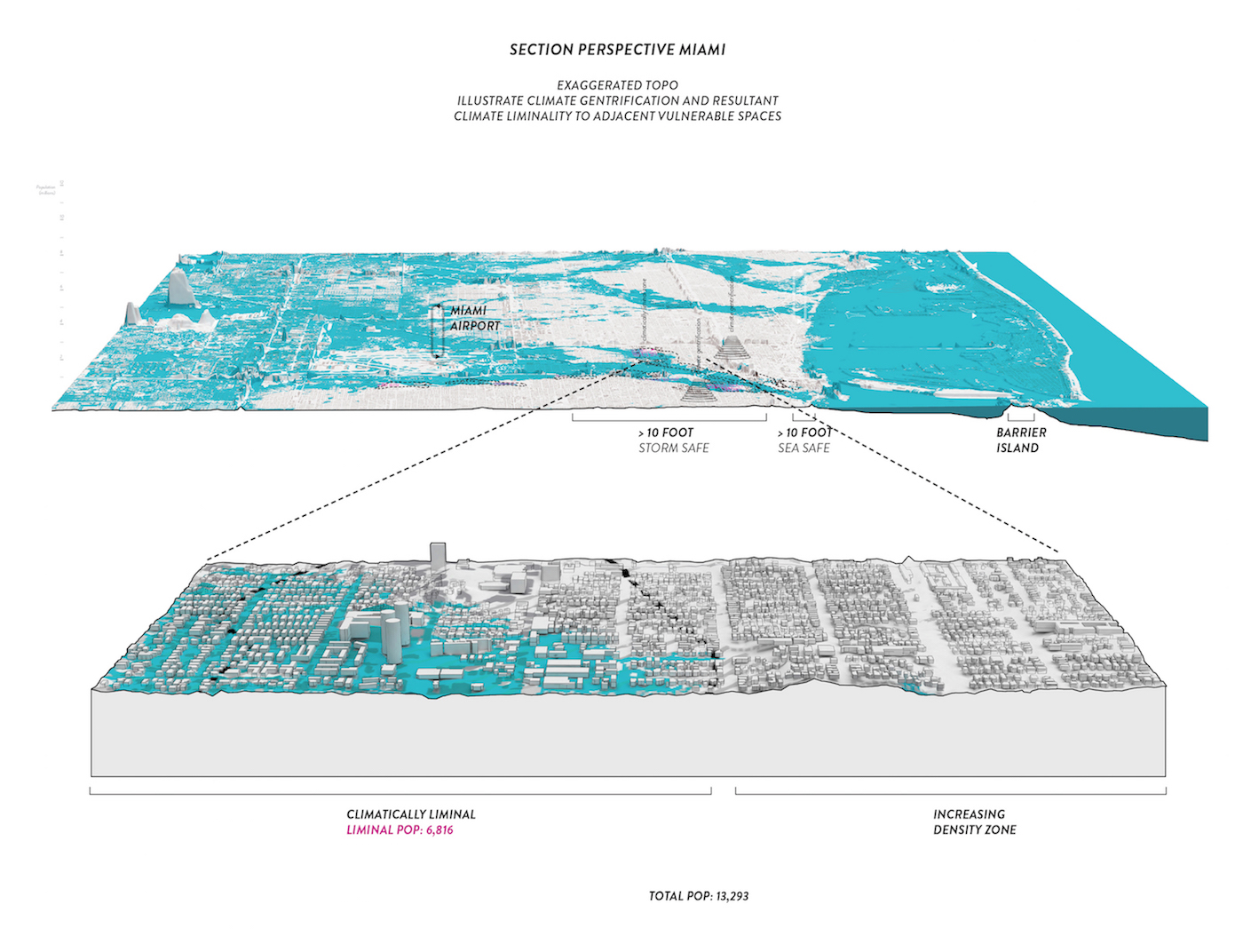

Climate Liminality: The Future Land-Water Interface

Hayden White (MAUD ’18)

This project proposes a tactic for the valorization of storm risk through the creation of storm water credits. These credits are utilized by vulnerable residents in ‘climatically liminal’ zones. Climatically liminal spaces of the urban area are spaces that previously held ecological values that have been destroyed, lending them to heightened risk of ecological and climate risk. The residents of climatically liminal spaces are economically immobile and are typically more physically immobile, elevating their level of risk. Residents will be outwith agencies boundary of initial investment and will be unable to relocate to gentrified high ground – locking them into an area that is increasingly susceptible to future losses.

A Storm Water Credit (SRC) scheme, coupled with transferable development rights (TDR) can create two avenues for relocation of vulnerable communities.

Avenue one targets short term mortgage lease where residents pool properties collectively to construct storm infrastructure and relocate from immediate risk zone to the periphery, taking their TDR with them. Generation of storm water credits (SRC’s) can recoup long term debts before effective inundation. This strategy works within Miami’s 2030 loan cut off (existing limitation).

In the second avenue developers collectivize and relocate residents, turning the land into SRC’s to satisfy credit obligations. Developers rehouse residents in high elevation zones that they own, thereby increasing land density. Developers receive 10% bonus FAR of commercial units for each vulnerable residential unit relocated. This scheme may extend the 2030 limit of development loans due to the increased adaptive capacity inherent in scheme.

At a practical scale the scheme offers multiple avenues for the relocation of vulnerable communities. Yet, at the theoretical level the scheme allows capital forces to become entangled with terrestrial climatic conditions through the valorization of storm risks. Over the longer term this scheme can create a cascading availability heuristic. This projects objectives to increase the adaptive capacity of vulnerable urban coastal areas through deep capital/ecological entanglement – meaning that if one system orients or shifts in a particular way, the other system will immediately orient in a complimentary way.

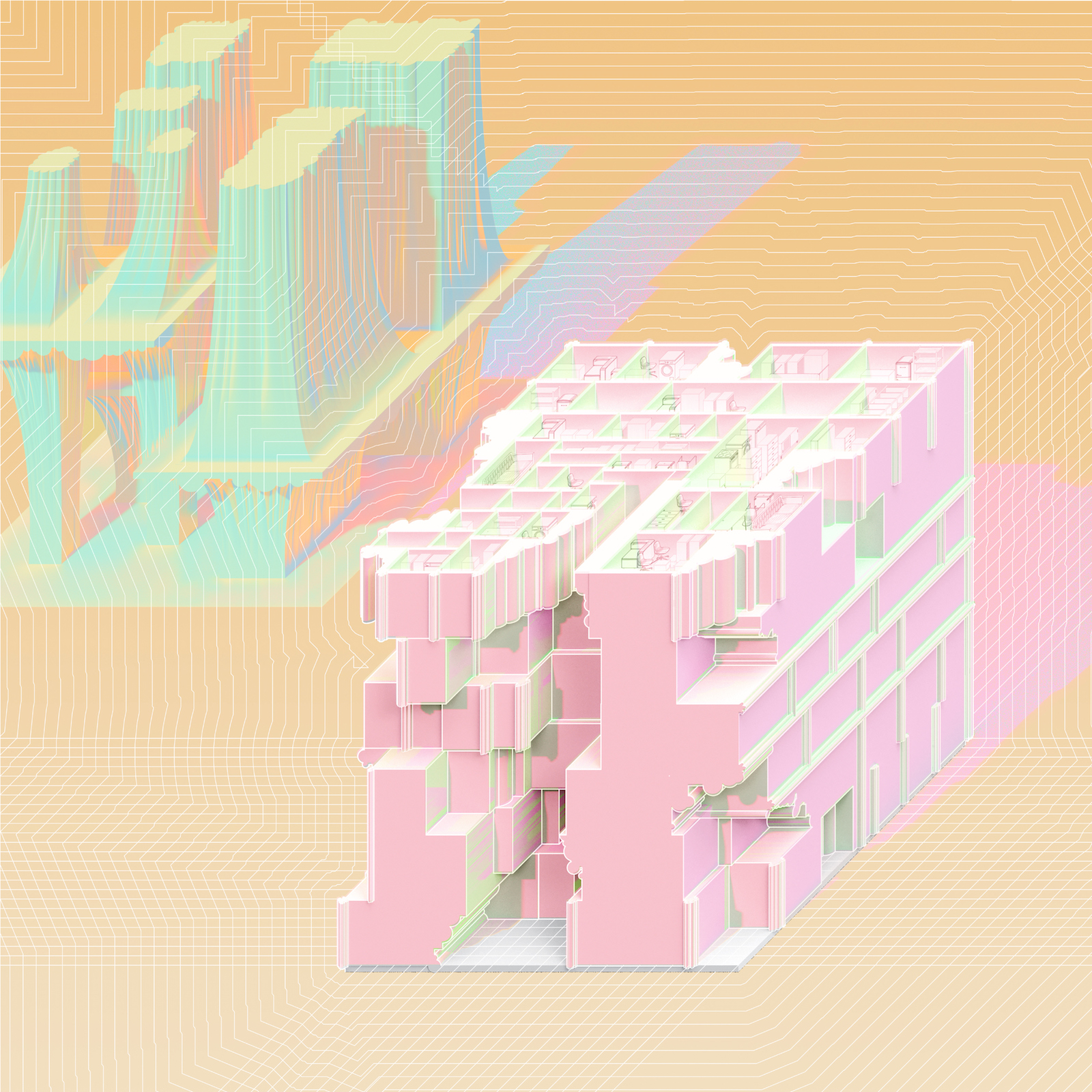

Death, Divorce, Down-sizing, Dislocation, and (Now) Display: A Self-Storage Center for a More Exhibitionist Future

Hyojin Kwon (MArch ’18)

Storage today finds itself compartmentalized into two categories: the visible and the invisible. As materialistic culture encourages self-identification with objects, visible storage through the shelf accommodates both easy access and curation of self-expression. However, in response to excess due to overconsumption, self-storage centers—one of the fastest growing industries in the United States—provide users with an invisible alternative to hide away a multitude of belongings. However, this image of the tightly packed storage room is not a new phenomenon. Sixteenth-century cabinets of curiosities contained enormous quantities of possessions that were curated and exhibited as archives of knowledge. This thesis asks: can cabinets of curiosities trigger a new typology of architecture for the contemporary self-storage center? Can such an establishment blur the distinctions between storage space, personal collection, and cultural museum?

The self-storage center for a near future presents collectors with many options for storage and display, both physical and digital, accommodating a wide range of storage formats under one roof. Public exhibition of personal possessions achieves an institutional character for the self-storage center, in which objects gain an architectural importance. Constant curation of objects resists hoarder culture, instead asking what belongs in storage when the previously dark and hidden becomes bright and showcased. As the new self-storage center takes on museological presentation and develops a distinct form, it acts as a monument to collections of the tangible and intangible within its urban context. However, this specific architecture does not subordinate its contents; rather, it provides a framework into which objects, people, and memories breathe life.

Kwon has extended work on this project into the 2018-2019 academic year, with support from the Irving Innovation Fellowship.

The research I have conducted with the support of the Irving Innovation Fellowship is, in a way, a continuation of my graduate thesis but with a few key modifications. While my thesis project was more of a speculative proposal envisioning a new architectural typology, my current fellowship research is an investigation of the typological forms needed to realize these alternative storage systems. In the typology I have developed, future self-storage centers would provide users with different storage types that accommodate a range of storage needs, types of access, and object display options. Each of the proposed storage formats responds to a different existing problem observed in contemporary self-storage centers. From this, I have aimed to develop a formal design process optimized for each storage system type. In my proposed storage format, the objects which people normal store out of site now gain an architectural importance, since their possessions are put on display as if in a museum. This provides a framework wherein objects, people, and memories are all on display, breathing life into what are otherwise the dark and hidden spaces of private storage.

In order to carry out my project, I have utilized the latest technologies that enable reciprocal 3-dimensional formal information exchange between the physical objects to be stored and digital modeling environments that allow me to experiment and test a variety of display solutions. This is primarily achieved through the use of 3d scanning techniques that digitize the real objects to be stored, and then implements versatile 3d-printing techniques to explore strategies for the fabrication, materiality, and further representation of my proposed typology. In order to further develop the unique architectural forms needed for this new form of self-storage center, the physical behavior of the objects is simulated through digital operations that include piling, stacking, draping, and packing, each of which is driven by software-based physics engines, thus allowing me to simulate these real-life scenarios. This consistent feedback between the operations of digitalization, simulation, and materialization processes will ultimately culminate in the development of prototypical architectural objects. My hope is that this research will result in a fabrication approach that can be scaled for implementation within architectural practice itself.

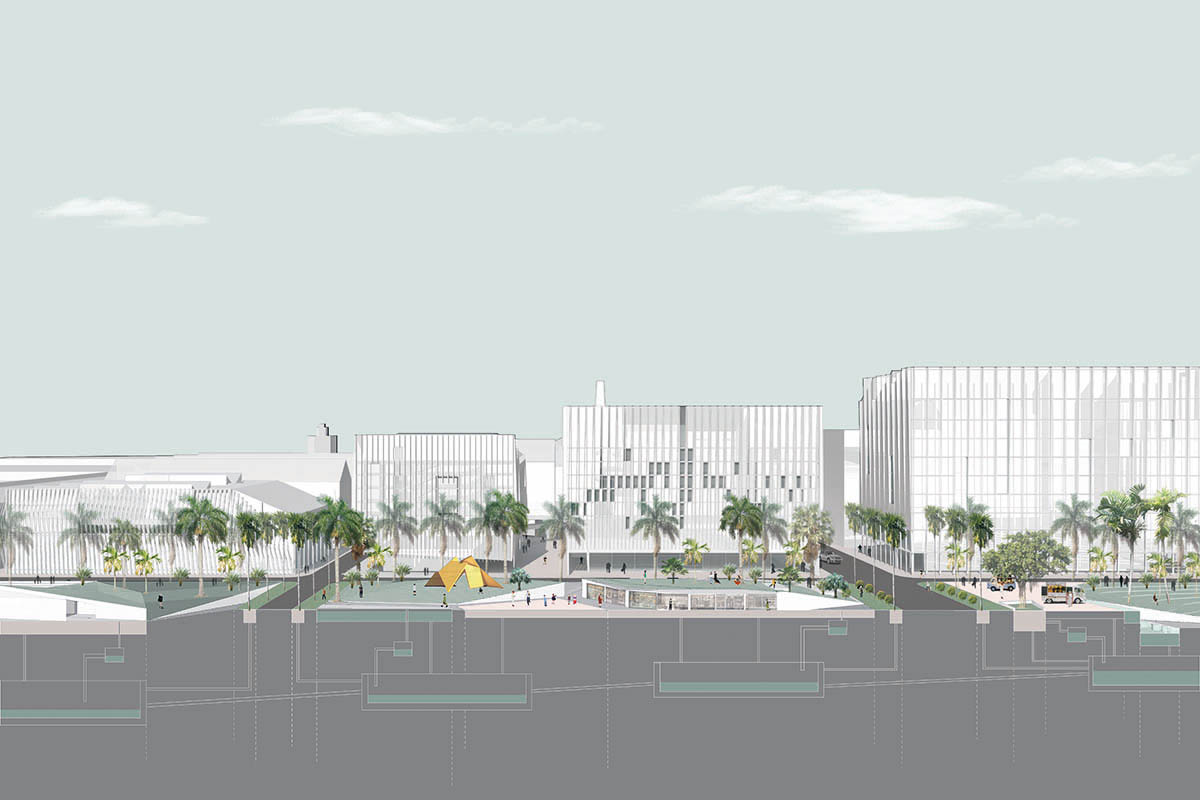

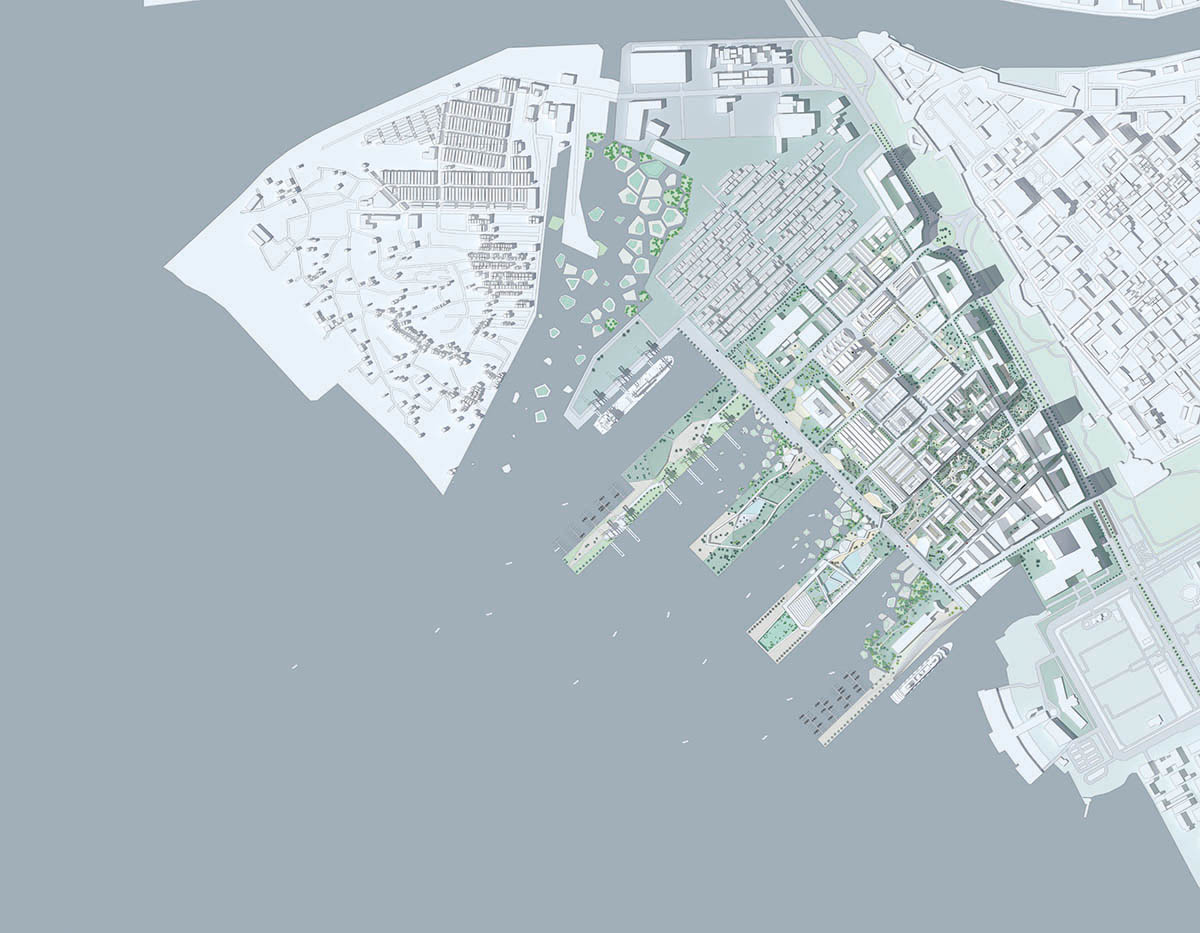

Manila Port: Gateway to the New Urban District

Chengzhe Zhang (MLA I ’19), Chenghao Lyu (MAUD ’18), Chi-Hsuan Wang (MArch I ’19)

In order to transform the industrial site of the Port Area into a newly generated city, our team, with a focus on future user groups and activities, introduces new typologies and programs to the site.

Considering the diverse user groups that relocated to the Port Area, we find opportunities to generate new housing typologies, which try to conquer the issue of hierarchical segregation within the Philippines, and intend to trigger mutual interactions between inhabitants of different backgrounds. We hope these interactions will not just take place within public spaces but also within residential areas and neighborhoods.

The housing typologies are designed to accommodate different user groups. The act of integration implies the core principle for these dwellings: augmentation of social equality and enhancement of communal synergy. After the visit to the Manila Port, our team recognized the importance of civic lives for locals, and how public activities have become a primary element of people’s daily routines in Filipino culture. Keeping this understanding in mind, our designs are driven around the concern of how to connect and reconnect each gesture back to the larger network, both conceptually and physically. Wishing to preserve the animated atmosphere within the residential area, all building modules are placed and reoriented around a central public core, which could be used for community gardens, libraries, small exhibition spaces, temporary theaters, or simply as playground for residents. The placement of the public core is intended to ensure its accessibility by all units, while still following general building codes. The public core, which begins from the ground level, also provides the opportunity to associate with and even structurally relate to adjacent typologies; we wish to extend this shared space into a greater system.

The introduction of these new dwelling strategies is not only to provide more organized spaces to revive the spirited environment, but also to produce job opportunities for future residents. Discovering how many working class populations suffer from poor working conditions and frequently need to be separated from their families to work, we develop a type of housing unit that allows the workers to reside with their families while working on-site, in nearby facilities, or on the port. The worker housing units are not meant as another form of mundane dormitory, but are rather designed as livable spaces that contain shared dwelling chambers and open areas.

The shared spaces for BOH units are interconnected; the interweaving chambers allow inhabitants from different units to interact and socialize. The shared chambers act like another corridor system revolving around the elevator and egress core, which allow the workers to travel freely through different levels.

The main objective for the mixed-user housing is to try to integrate people from different backgrounds and minimize segregation by means of positive interaction. To activate the neighborhood, and even the surrounding communities, the residential tower is supported by a central atrium connecting the terrace garden and tower garden. This central atrium could be used for a variety purposes, such as a library, small classrooms, or simply open green space. The continuous public spaces within this piece of architecture will allow a series of interactions between residents.

We consider the school as one of the most important public facilities within our new urban district. It would provide equal educational opportunities for kids from different social classes, and more importantly, serve not only as an educational space, but also as a community center providing shared cultural and recreational public facilities that can be used by all the people from the community.

The use of this space can be divided into two time periods. During the day, it would function as a school; after school, some of its facilities would open to the public, such as the basketball courts, cafeteria, library, auditorium, gallery, gathering spaces, and art-related classrooms (for music, dancing, fine arts), among other areas.

The spatial character of the educational space is inspired by the spontaneous settlement in Manila. There are two main inspirations. The first is the extraordinary diversity of the space within the spontaneous settlements. From our on-site experience, we find that kids gather and play in many spaces, from the rooftops to the streets, from terraces to courtyards. We think these void spaces of various sizes between building volumes provide opportunities for kids to occupy and use by themselves, and this play can stimulate their curiosity. The second inspiration is social equality. When we look at photographs of the spontaneous settlement in the city, we can immediately acknowledge that human beings live under the same sky. Conceptually, for the school and cultural center, everyone would study, communicate, and play under one single large roof. We see this as a metaphor of social equality: under this roof, people would share the space no matter where they come from.

We believe that the flexible spatial arrangement can create a unique learning environment for all of Manila.

Pasig River: Fluid Occupancies

Emmanuel Coloma (MLA I ’18), Rose Lee (MLA I ’18), Luisa Piñeros Sánchez (MArch I ’19)

A place of extremes, Manila is a megacity at a critical juncture. Since World War II, the Pasig River, which runs through the heart of the city, has been regarded as a source of unsightly pollution, damaging floods, and an interruptive physical barrier. Our design proposal rests upon the belief that the key to a vibrant future is to turn the river into a resource rather than a hindrance to the citizens.

Through examining the complex relationships among river ecology, local economy, transportation and public space, we propose an adaptive design that brings the Manileño to the forefront by allowing the Pasig River and its edges to anticipate rising waters, transportation development, and an ever-burgeoning diverse population. We believe in increasing the value of the Pasig River waterfront for all Manileños by providing an opportunity for them to attain resources, acquire knowledge, and take ownership of the land they live on.

The project is located in the Pasig River, a 25-kilometer-long river that bisects Manila, Philippines, the densest city in the world. Though called a river, it is actually a tidal estuary that connects the saltwater Manila Bay with the freshwater Laguna de Bay. The flow of water fluctuates depending on whether it is the dry or wet season.

For the scope of the project, we primarily focused on what is now a vacant lot in front of the Intramuros wall, approximately 9,500 square meters (1 hectare). Currently closed off to the public, it is a space we decided to focus on due to both its historic location and proximity to the Plaza de Mexico ferry terminal and preexisting pedestrian bridge to Binondo.

In addition, we also looked into two other potential “hub” locations situated next to the Lawton ferry terminal and the car-dominated Roxas Bridge at the mouth of the Pasig River. Exploring the potential of these two sites also lent two alternatives of our design proposal under different conditions to demonstrate its adaptability to multiple situations.

Intramuros: Redefining Restoration

Zheng Alan Cong (MLA I ’19), Peilin Li (MLA I ’20), Paris Nelson (MLA I ’19), Bailun Zhang (MLA I ’19)

The identity of Intramuros in the context of Greater Manila has always been in question—its very name immediately separates this historic center from the city beyond the walls, or the “extramuros.” While physical boundaries have become more relaxed (or simply changed in form)—the fortification walls partially destroyed, the moat filled in—the legacy of Intramuros’s identity as a “walled-in city” has held on, isolating the core from contemporary urban Manila as it develops. We believe that Intramuros can no longer exist as an urban island. With its richly layered urban and architectural history, it has much to contribute in negotiating with growing issues of urban tension and participating in the conversation of Manila’s future identity.

We would like to recognize the significant work performed by the Intramuros Administration (IA) since 1979 to restore and revitalize this important historic area. In approaching this site, we wholeheartedly share their goals of community engagement, and ensuring that Intramuros continues to be a destination and resource for both tourists and locals of Manila. We especially hope to build upon their past and current initiatives for renewed local participation in the public spaces of Intramuros.

While we hope to build upon the success of the IA’s public events and community engagement initiatives, we believe that an alternative approach to the existing attitude toward historic preservation and restoration is critical for Intramuros’s continued participation in the rapidly evolving urban landscape of Greater Manila. Rather than rebuilding the site to perfectly imitate its historic form, we hope to learn from and identify thevalue in the layered contributions to the area throughout its history, acknowledging the history of Intramuros in a way that works for contemporary and future Manila.

Our ultimate goal is to create a new network of public space that integrates programming that serves all local populations of Intramuros and Greater Manila. In our visit to the site, we observed how the diverse population groups within the walls are informally zoned (the student belt; the tourist route with adjacent office pockets as public front; the hidden informal settler center), and how this creates division between these people and their experiences of Intramuros. We believe that this is a problem inextricable from the lack of public space within and around the walls (indicative of a pervasive problem in Manila) and that the introduction of a new system of public space will create zones of interface between populations vital to the vibrant Intramuros urban life envisioned by the IA. Through a phased plan that reclaims the historic wall and moat and integrates underutilized spaces within Intramuros’s walls, we hope to transform existing spaces of boundary and exclusion into spaces of interaction and integration.

Informed by the historic plans of destroyed sacred structures, the contemporary recall filters light and shadow to recall and celebrate anew thoughtful and contemplative spaces.