Terra Fluxus

Shizheng Geng (MAUD ’21) and Youngju Kim (MAUD ’21)

Our project, ‘Terra Fluxus,’ aims to revitalize and reconstruct the cultural identity of the urban peripheral logistics campus in Westwood with two main strategies: the first one is to reverse the long-lasting process of cutting the topography of woodland to fill the wetland; the second is to amplify the capacity of wetland and industry for ephemeral events to make our site vibrant with attractive cultural identity. The title of our project is borrowed from the title of an essay by James Corner where he used this term to describe the shifting processes coursing through and across the urban field. When we compared the history photos with the current condition on our site, we found that there is a long-lasting and on-going process of cutting the topography of woodland to fill the wetland. Along with a long-term process of re-contouring, we explored the capacity of wetland and existing logistics industry. We see this seasonality and temporality as a big opportunity to hybridize nature, industry, and recreational culture in our site. This project is not about restoring nature back to its former state, but rather re-contouring to provide spaces for all the existing fluxes, that is, wetland, industry, and recreational activities, that will make our site vibrant and playful.

Ecological Machines

Simon Escabi Santos (MLA I AP ’20)

The city of Santiago, Chile, is located on a low point on the skirts of the Andes mountain range. This basin situation, which results in a lack of wind currents during most of the year coupled with a low precipitation average, produces the prefect conditions for a high count of air pollutants.

This project aims to improve local air quality in low income neighborhoods in Santiago through the coupling of long term and short-term strategies. It consists of a community operated urban tree nursery that will slowly populate the streets and parks surrounding the project site, as well as protected play and leisure areas maintained through a system of Phyto-filtering. As a result, the area is transformed into a new public space for the neighborhood.

In the urban tree nursery, the trees will go through three stages before being dispatched to their final location along the streets or parks of the neighborhood. First, an initial seed germination, which happens in special containers. Next, the plant will be moved to a small part of the plot until it attains the stage of sapling and from there it will be moved to the larger part of the plot where it will grow until it attains a DBH (diameter at breast height) of 18 to 20 cm. At this point the tree can be relocated to its final location. This creates a pattern of crop rotation that will constantly transform the park.

The second strategy, Phyto-filtering, is based on several studies that have addressed the topic of the capacity of certain trees to retain large amounts of particulate material. The Phyto-filtering strategy proposes to plant the most efficient species for particulate matter capture, using the planting patterns of traditional windbreaks. These will create protected spaces of different characteristics that will provide a variety of activities with cleaner air.

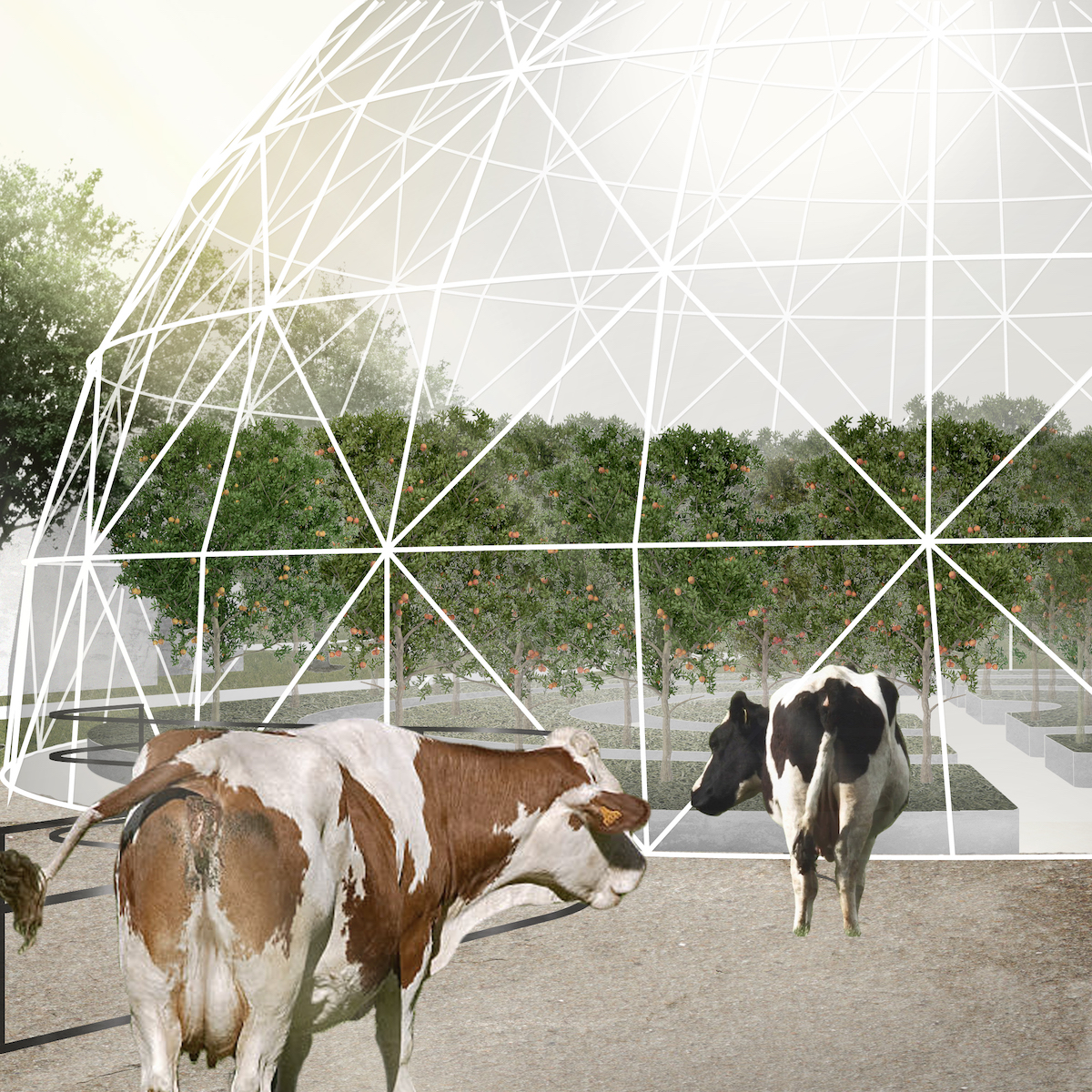

At The Dinner Table — Green to Orange: Building Ireland’s food security and identity

Jiyun Jeong (MLA I ’19)

Food reveals the culture and identity of the place. What and how people grow on the land constructs the landscape and what people consume shapes their identity and health. This study focuses on Irish farming and its relation to the Irish landscape, not only in the context of Brexit but also engaging with climate change. The current Irish landscape contributes in a major way to Ireland’s sheep and cattle farming. However, what if the Irish landscape becomes no longer green and placed at risk due to climate change?

The development of agriculture has moved away from crop growing to animal farming. Currently, dairy has become a specialized type of farming and less than 3% of Irish farmers grow vegetables and fruits. However, Ireland is predicted to be seriously impacted by climate change and it will put the unique feature of the Irish landscape and its current primary crops, like potatoes, at risk. In terms of Brexit, the deal could have a major impact on Irish fruit and vegetable importers and wholesalers, meaning shortages and higher prices for consumers.

This indoor landscape system would allow farmers to test and grow new potential species in preparation for climate change. One existing farm in Strabane is selected as a testbed since this farm has already started embracing new technology and innovative systems for farming. Cows’ steamy breath will be used as a form of heating and expired carbonic gas will quicken and promote vegetation. Moreover, the moisture from cow breath will save watering and the waste from cows will be reused as a form of fertilization. Oranges in the greenhouse will eventually come out to the field when the climate gets suitable in 60 years. The indoor landscape system will be reused for other species in future adaptations. This project will eventually establish Ireland’s food security and change their dinner table.

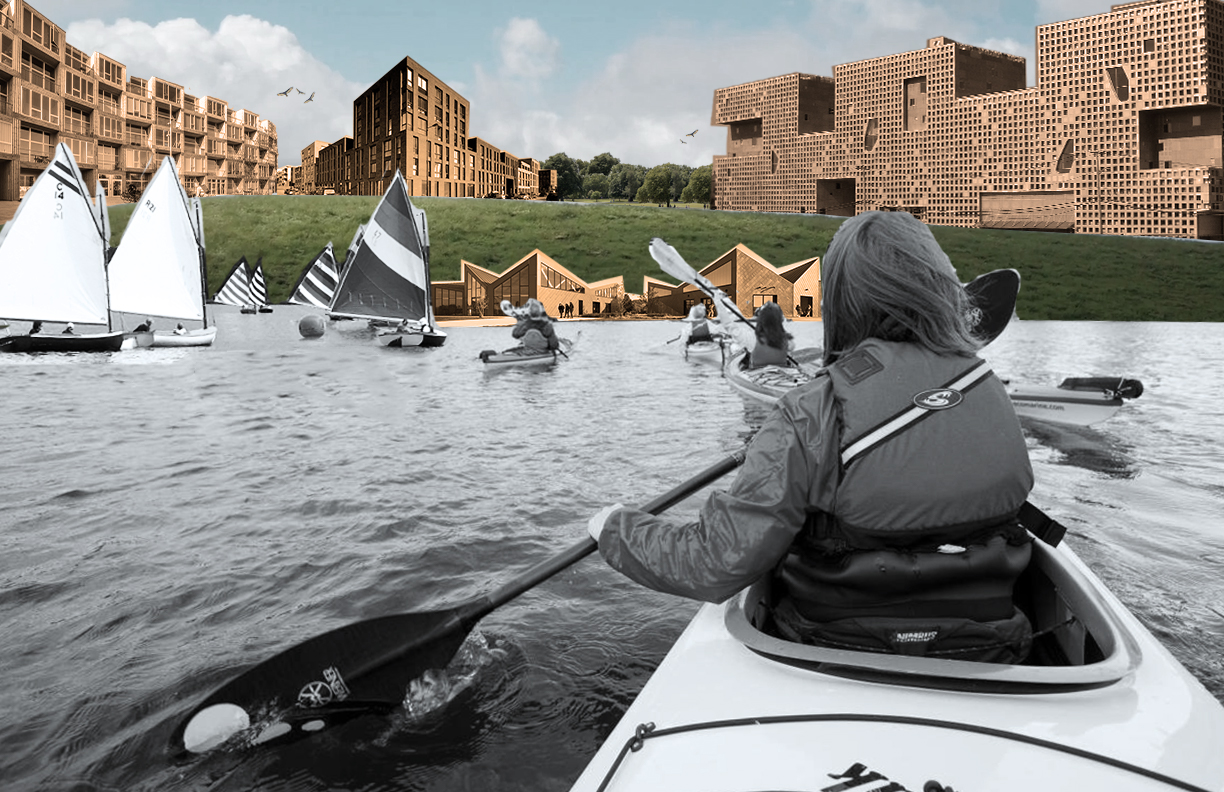

Creating Higher Ground in Boston’s Seaport

Amelia Muller (MUP ’20)

In September 2018, the City of Boston published estimates projecting the city’s population will reach almost 760,000 people by the year 2030. To meet the population growth and requisite housing needs, Boston has increased its overall housing goal to 69,000 units by 2030. Siting that growth requires significant land capacity in a city that is already land strapped. The industrial land between the Seaport and South Boston, east of the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, represents a prime opportunity for development of new housing and amenities to serve those residents. However, this plan area and much of the surrounding land is under serious threat of sea level rise, projected along a similar timeline to population growth.

To develop housing in this area without addressing the threat of sea level rise would be deeply irresponsible. Thus, this plan seeks to create higher ground for development through “cut-and-fill” of the Reserve Channel and the inclusion of mediating green space between new development and the water. In addition to mitigating the harmful effects of climate events, this landscape will create a more enticing arrival experience from the nearby cruise terminal, provide a respite from the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, and build on the success of Lawn on D to create vital open space for the Seaport and South Boston.

The density scheme proposed in the plan seeks to mediate the superblocks and higher heights of the Seaport with the lower heights of South Boston through a step-down approach from north to south.

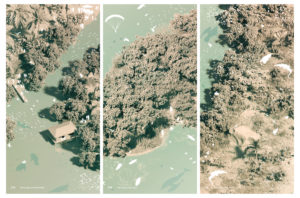

Nourishing Captiva

Naoko Asno, Anna Curtis-Heald, Jenjira Holmes, Phia Sennett (all MLA I ’19)

On March 5, 2019, Captiva Island held a referendum on beach renourishment. 123 ‘yes’ votes catalyzed 30 million dollars in spending. 17 voted no.

In contrast to the erosive forces that actually grow coasts, beach renourishment is an erosion prevention technique used by Captiva Island for the past 50 years. In a predominantly sandy biome, what does erosion prevention mean?

Captivans are presented with a binary decision, YES OR NO, for or against. But as designers we like to imagine alternatives. In a context where the beach is invented and dredge is designed, why not imagine another placement strategy that works WITH the movement of the barrier, rather than against it?

We offer strategies for land building on the bay-side of Captiva, by using sand to support the natural landward movement of the barrier formation.

We imagine a political process that transcends the binary. Does sand belong on the gulf-side only? Is the only way to enjoy Captiva through a static 5 mile long beach? Why not distribute the 900,000 cubic yards of sand on the bay-side in order to jump start the land building that has been arrested by such erosion preventions measures?

Can sand act as a catalyst for mangrove growth, support dune habitat, and facilitate breach dynamics, supporting ecological richness and transformation? Can plants be allowed to act as space makers?

Our project illustrates this through nourishing in three areas: a sandbar, a golf course, and the narrowest and most vulnerable stretch of the island.

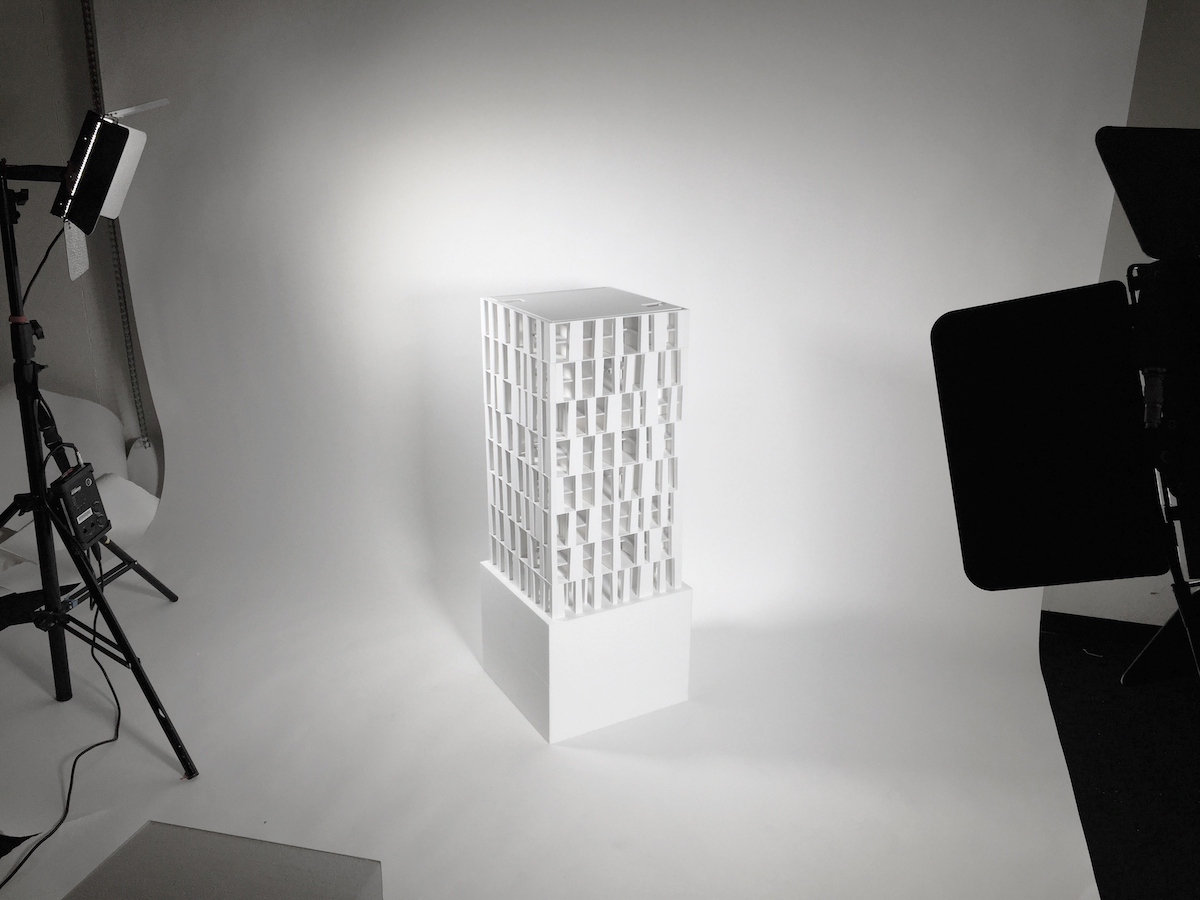

The New Generic

Daniel Garcia (MArch II ’20)

In, The Generic City, Rem Koolhaas asks us to consider the disadvantages of identity, and conversely, the advantages of blankness. He asserts that a city bound to its identity resists expansion, interpretation, and renewal. Koolhaas goes on to define and embrace the idea of a generic city as one that is liberated from the straight-jacket of identity, history, and context. “It is a city without history. It is big enough for everybody. It is easy.”

Miami’s strong identities and multiple histories beg for an architecture of multiplicities. For this reason, a project for the Miami Design District that provides adaptable spaces for living and working should be neither wholly generic nor specific; it should situate itself somewhere between the two. The project alludes to the low-rise urbanism of the surrounding context by dispersing a series of pavilions around a site on the southeastern edge of the Design District and continues by stacking the pavilions into two towers, creating a vertical mat urbanism that approximates the public and semi-public spatial sequences of the neighborhood. Courts, passageways, and stairways give the Design District its character but these features are deployed here as an inherent critique of the low-density development which lacks the programmatic diversity of a rich urban fabric. The facade is comprised of massive precast concrete panels that span two floors and are used to mitigate climate and solar exposure. Large arcades appear around the perimeter of the towers as abstractions of the pervasive balcony typology of Miami beach high-rises.

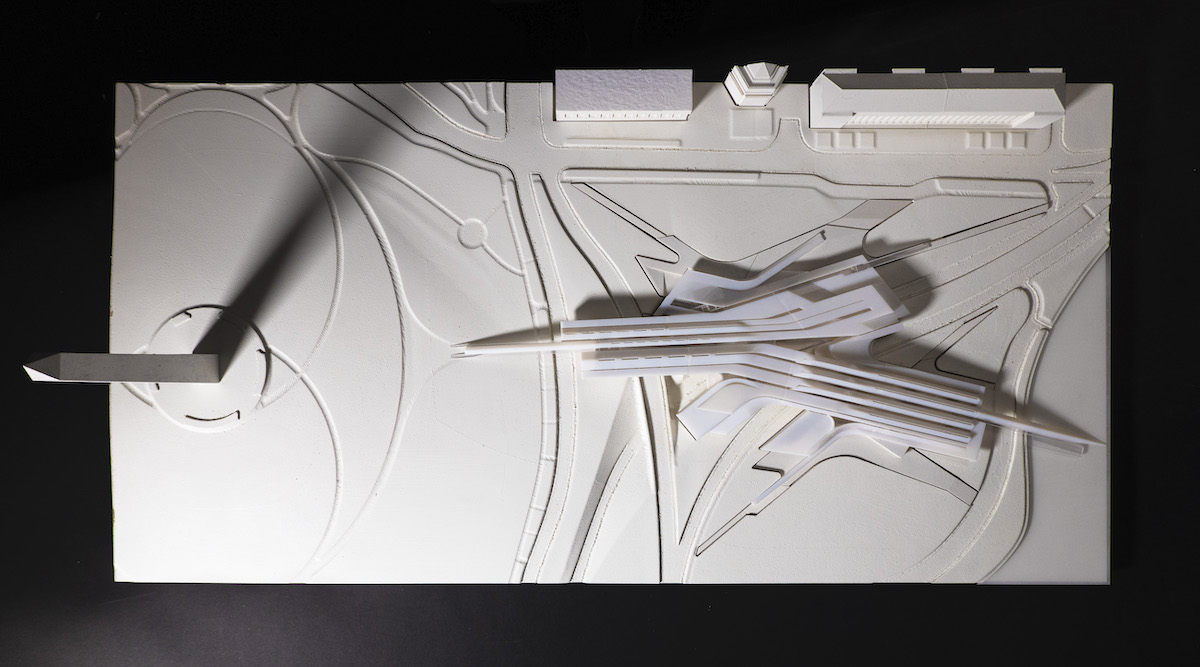

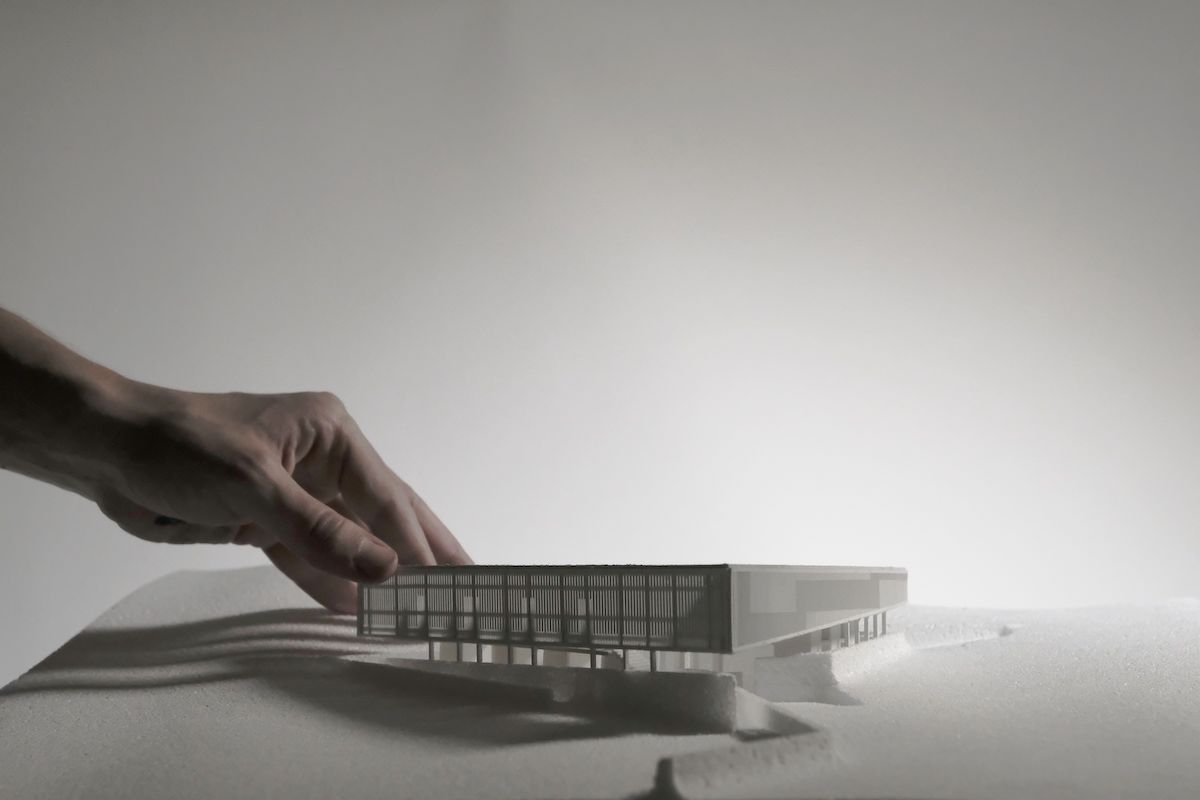

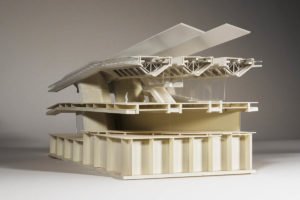

Surface of Confluence, An Infrastructural Museum on the National Mall

Zi Meng (MArch I AP ’21)

This project intends to synthetize multiple architectural interests into a wholistic form. Several different aspects including typological organization, social activity, contextual influence and historical connotations are analyzed and instrumentalized to generate an idiosyncratic formal language – the confluence bundled roof system. The project proposes a new form of museum for DC that fuses the infrastructural quality of the bridge together with the singular characteristics of the museum. The geometry of the museum is a product of negotiation between its internal organization of programs and its circulatory bridging functionalities. The confluence roof system is a formal, structural and tectonic solution informed both by the site context and typological study of museums. Its geometry and structural property are adaptive to the complex contextual influences and programmatic requirements. The conflicting and conforming flow of the roof bundles formally responding to the poignant status of the highway severed site, at the same time creating a walkable roof surface that is bridging and suturing the fragmented site parcels. The roof bundle system also provides a porous surface, while walking on the roof bridge of the museum, the visitors can frequently drip down and experience the museum space without going inside of the museum.

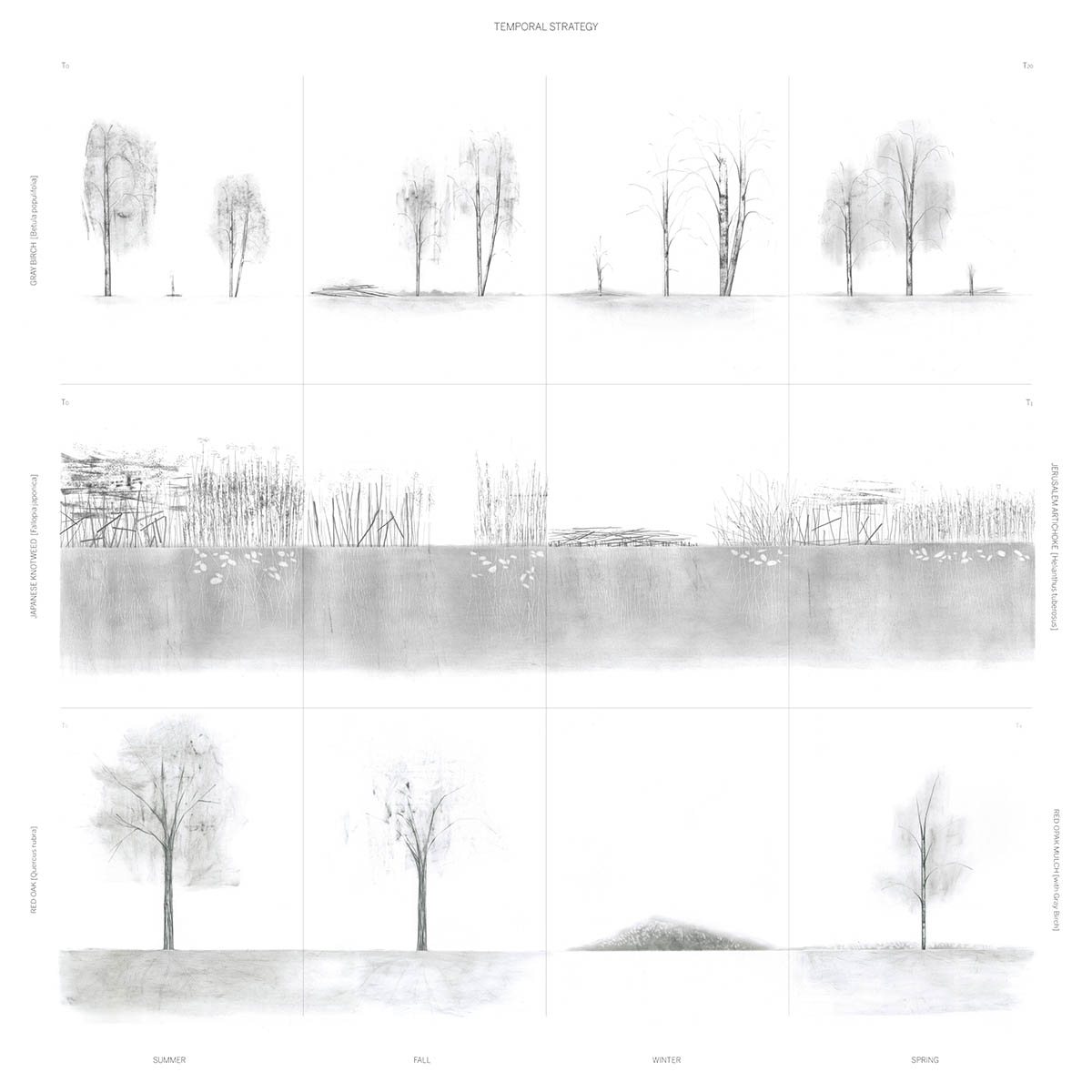

Vegetation Orientation: Franklin Park’s Way

Chelsea Dombroskie (MLA I ’21)

Franklin Park is challenging to navigate. Vegetation Orientation asks how a design can bring clarity to a disorienting area of the park, a clarity that is embedded in the site and integrated with existing conditions. The result is a series of wayfindings defined by vegetation. The ways have their own micro-identities and in the context of the larger park, act as a threshold between existing zones of activity.

Way 1 is an observation of invasive Japanese Knotweed that currently exists in patches on site and is difficult to eradicate. Within this way Knotweed can stay, expand in the specified areas and have an identity that is reframed positively and can be maintained through harvesting driven by community engagement. Young shoots cut in early spring are edible. Jerusalem Artichoke, edible and believed to balance Knotweed’s invasive qualities, will be introduced along this way.

Way 2, is an expansion of gray birch that currently exists in small numbers on site. As the dominant red oak canopy in the park nears its end, mulch can be made to support the new birch life. Seeds need exposed ground to take root; a mulching pattern, will allow the birch to create a variety of spacing and experiences along this way.

Way 3 proposes directional breaks into the exiting parking lot asphalt to allow grass between, linking grassy playstead to grassy golf course. An integrated parking lot in which edges become diffused, better support the social space it already is.

Throughout this project I asked how our understanding and energy toward invasive species can shift from worthless to valuable. Olmstead is believed to be an early supporter of knotweed’s introduction into the US, is it our responsibility then to eradicate it or adapt with it? Can the dying canopy can support new plant growth? How can existing conditions be reframed to better support community use of the park?

MEMORY of the CORS (center for ornithological research and sanatorium) in Nahant Beach

Hee Young Pyun (MArch II ’20)

For the studio, each student had to select a site and was assigned their own program by the instructors. My site was the Nahant Beach in Massachusetts, and I was assigned the program of the CORS – center for ornithological research and sanatorium.

A place becomes memories, and memories become dreams. This process of ‘place – memory – dream’ can be reversed, as our dreams give a meaning to our memory, and memory gives a meaning to a place. We cannot share our memory, but we can share the moments. And our memories of the place accumulated over time become a place itself. Rather than looking for the origin of memory, we believe in memory constantly on the move.

Far Niente

Alexandros Spentzaris (March II ’19)

Can we think of another, smaller scale of housing?

How can we “live together” instead of “living next to each other?”

Can co-living be more than just a way to decrease domestic costs? Can living together be a value in itself?

The studio focused on small scale housing, mainly concentrating on housing arrangements of 7-12 domestic units. The project focuses on contemporary co-living in Sea Ranch, California. Rejecting co-living as a mere way to reduce domestic costs, the work initiated with an analysis on pre-modern typologies where co-living was an end to itself such as monasteries, mosques, and convents. This analysis formed the main concept for co-living as a super-house; a unified single space where the private and public activities are inextricably intertwined. All of the everyday activities that in the context of the global north are considered dysfunctional or at least useless, are now, in a paradoxical reversal considered to be the necessary condition of communal isolation. “Far Niente” is not a pessimistic project but it rather marks an impossibility of the concept of “stepping back” today. “Far Niente” or “doing nothing” is an active meaninglessness that performs as a counteractivity to a (still) hyper-modernist context, obsessed with efficiency, functionality and objectivity. The apartment is structured as a unified single space divided by mobile elements and curtains. A swimming pool is supposed to give a rhythm of a body’s temporality. All services are performed through the existence of common services that distributes products to the units on demand.