A Generosity Beyond Means

Jonathan Ng (MArch I ’22) and Edda Steingrimsdottir (MArch I ’22)

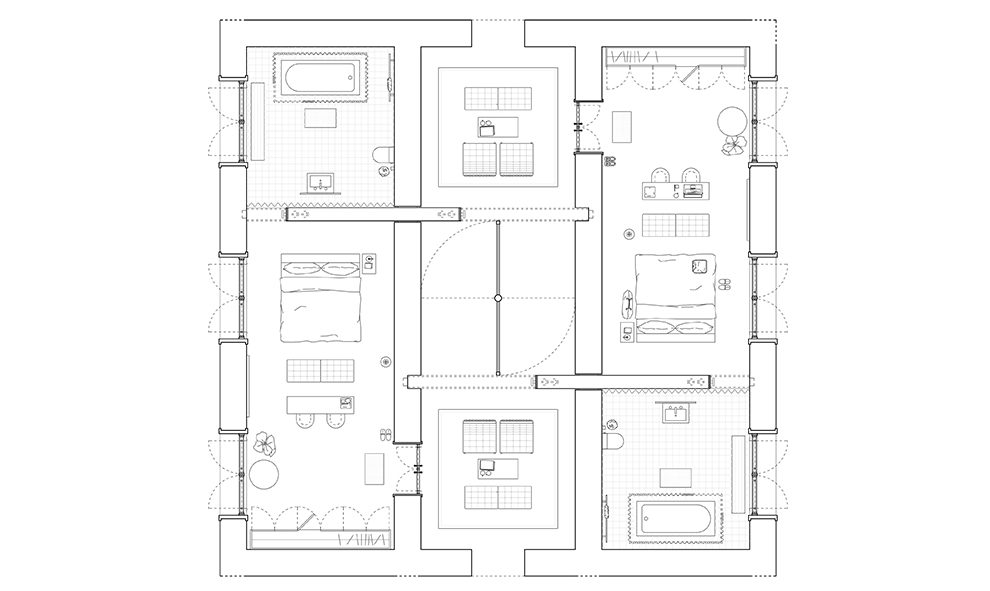

Mass housing faces the persistent challenge of creating economically accessible living spaces in increasingly densely populated cities. Housing units are often devoid of elements that contribute to one’s quality of life, being perceived as indulgent rather than essential. Through the manipulation of the ground, the interior wall, the facade and the roof, this project creates the perception of an expanded lived space.

In contrast to the densely packed triple-deckers in Boston’s Jamaica Plain (JP), the four housing bars of this project are lifted to create a generous open ground floor. Within four housing bars, the units are deliberately arranged heterogeneously, resisting the overly hierarchical or repetitious nature typical of housing blocks. The manipulation of interior walls creates spatial generosity unique to each unit type.

The facade is not just an external face for the public. It is a projective frame through which residents can establish connections beyond the limits of their units. This evokes a new definition of community, one that transcends proximity and forges new relationships from within, across, and beyond each unit.

The roof of the four housing bars is unified by a spherical subtraction, inverting the typical condition of a perimeter by establishing different horizon lines throughout the roof. It offers a generous new private ground for residents to form connections to the horizon, the sky, and the city beyond.

This project invites us to consider how the manipulation of space can be used to enhance our quality of life. It shifts our perception from an absolute scale or material wealth to the relationship between the subject and their surroundings. Expanding our definition of a quality living environment to one no longer limited by economic ability, the project provides for all, a generosity beyond means.

Le Circuit Périphérique

Jorge Ituarte-Arreola (MAUD ’21), Alex Kozak (MDes REBE ’21), Melissa Ponce (MDes REBE ’21), and Isaac Tejeira (MAUD ’21)

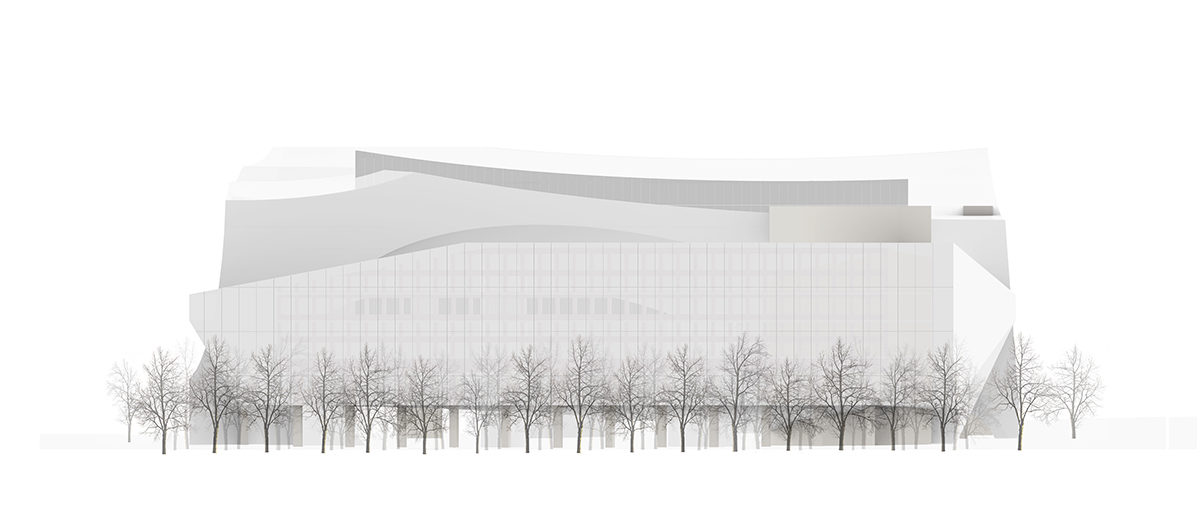

The Paris Metropolitan region has experienced significant growth over the past decade. Major infrastructure projects like the Gran Paris Express will reshape Paris and its surroundings by increasing connectivity and mobility for people living outside the city center. This project located along the Périphérique in Bagnolet on the eastern inner-rim of Paris, serves as an opportunity to transform and better connect Paris to its suburbs, while at the same time revitalizing and celebrating the neighborhood’s unique character. This major office and retail master development project aims to revitalize and enliven the Bagnolet area and provide much-needed community amenities for the residents of Bagnolet. We hope the project will serve as a catalyst to attract new investment and development in the area, transforming the surrounding neighborhoods and benefitting the residents of the community.

The project seeks to welcome the residents of Bagnolet and provide health, wellness, community amenities, and entrepreneurship opportunities not only for our office users, but all stakeholders in the surrounding community. The project offers more than 2,000 sqm of subsidized retail space for local business owners and subsidized space for the community to celebrate the vast cultural diversity of residents within Bagnolet. The project recognizes the critical need for public space in the community and provides a multitude of public courtyards, parks, and promenades throughout the master plan. With over 50 proposed activities for the public space, the project provides an alphabet of activities to enliven the neighborhood and creates a 24-hour destination for residents and visitors alike.

Rethinking the “Room” through the Pandemic: Isolation, Openness, and Confrontation

Clara Mu He (MArch I ’24)

Based on a formal and theoretical examination of the field hospital—a type of medical architecture that has emerged more widely under COVID-19—this project proposes a critical speculation on how the pandemic will reshape our engagement with public spaces. As pandemics always provide a ground for the rehearsal of utopian governance, it is arguable that the field hospital has become the perfect stage set for this rehearsal. Highly controlled, ordered, surveilled yet surprisingly open, the field hospital environment puts all occupants in a strange condition of intimate confrontation. Spatial privacy is eradicated yet social isolation is bolstered, forcing the occupants to assume a state of mutual-surveillance and self-discipline.

From this observation, the project seeks to engage critically with the assumed conventions of a community house, through evoking the paradoxical relationship between openness and isolation, distance and intimacy, that is brought to the fore in the field hospital. Through implementing the architectural device of a convertible core, the implied spatial and visual connectivity of the enfilade is destabilized, entailing a spectrum of conditions in the ground floor plan. On one end of the spectrum, the rooms are visually connected but spatially isolated, and on the other end they are visually isolated but spatially connected. On the second floor, the convertible cores create a dynamic interplay between the public and the private. They are neither visually nor spatially connected, but are linked through a common tactile operation, thereby achieving a kind of uncanny intimacy within isolation and distance.

27 Pillars

Alejandra Avalos Guerrero (MArch II ’21)

A little building in a little plot.

The building is a rectangle protected and organized by a forest of natural and artificial pillars. Each of these twenty-seven pillars has different sizes, shapes, and materials. On the inside, six of these pillars are gently misaligned to the rest. Sometimes, the pillars have walls that don‘t touch the floor, you can always see everyone’s shoes or the garden.

A very simple yet very complex building.

Food on Mixed Ontology

Sean Kim (MArch II/ MDes ADPD ’22) and Ge Zhou (MArch II ’21)

Food and architecture share many similarities. They both require various ingredients and are invested in construction methods or techniques. They satisfy basic human needs, while also becoming important cultural products. They are activities through which humanity mediates its relationship to the surrounding context. In short, both fields are concerned with how their design functions, looks, and what a New York Times lifestyle column might think of it.

Since food and architecture are both complicated and messy cultural products, what would happen if architects became chefs? This project begins with generating an avatar who becomes a chef. Then, there is a random-chance game where the chef cracks fortune cookies with a different architectural theory inside each cookie. The resulting fortune asks for a chef who will use smooth surfaces as ingredients, defamiliarization as technique, and a finished meal that is visually ambivalent.

Designing, making, and documenting the four-course meal led us to think about contemporary architecture theory in a less restricted way. Food doesn’t carry the same baggage as a sheet of chipboard and definitely less than a precast concrete panel. Food has afforded us the opportunity to play with these ideas quickly—but sincerely. The best part is: even when you fail, you can eat it!

J. Edgar’s Mask

Yifan Wang (MLA I AP ’21)

When the hyperplastic organ of the Federal Bureau of Investigation started to grow outward/northward from the body of Department of Justice, crossing the diagonal Pennsylvania Avenue, our story began. Responding to the iterative reviews from various committees to establish a national profile flanking the procession marching all the way up to Capital Hill, the façade of this brutal building was constructed into an infinite wrap of concrete grating as part of D.C.’s national identity. What has been mysteriously masked behind as well is the titular institutional body of J. Edgar Hoover.

In the proposed future, a reopened D Street is peeled off of the pivotal front of the site along Pennsylvania Avenue, and the triangular residue will be re-sculpted into an exhibiting space. The original complex, from D to E, will be hollowed and lifted to restore the very first ideal of the modernism scheme: to involve and consolidate the public. Detached from its bygone face, the new block is in need of a fresh masking project. Taking advantage of the capacious setbacks designated to the dreary bunker, a new mask will be fabricated around in the geometry of Mickey Mouse’s anatomy (Read about Walt Disney’s link to the F.B.I. and J. Edgar Hoover in the New York Times). Its four elevations are no longer homogeneous, in order to genuinely reestablish the dialogue with its dynamic surroundings. The FBI rumor goes on with this project, and people will recognize the masqueraded character through the exposed concrete grids. But they will definitely be perplexed by the semi-pervious vizard, the camouflaged plaza, and the enigmatic persona beneath the mask.

String-pieced Columns

Cecilia Huber (MLA ’20)

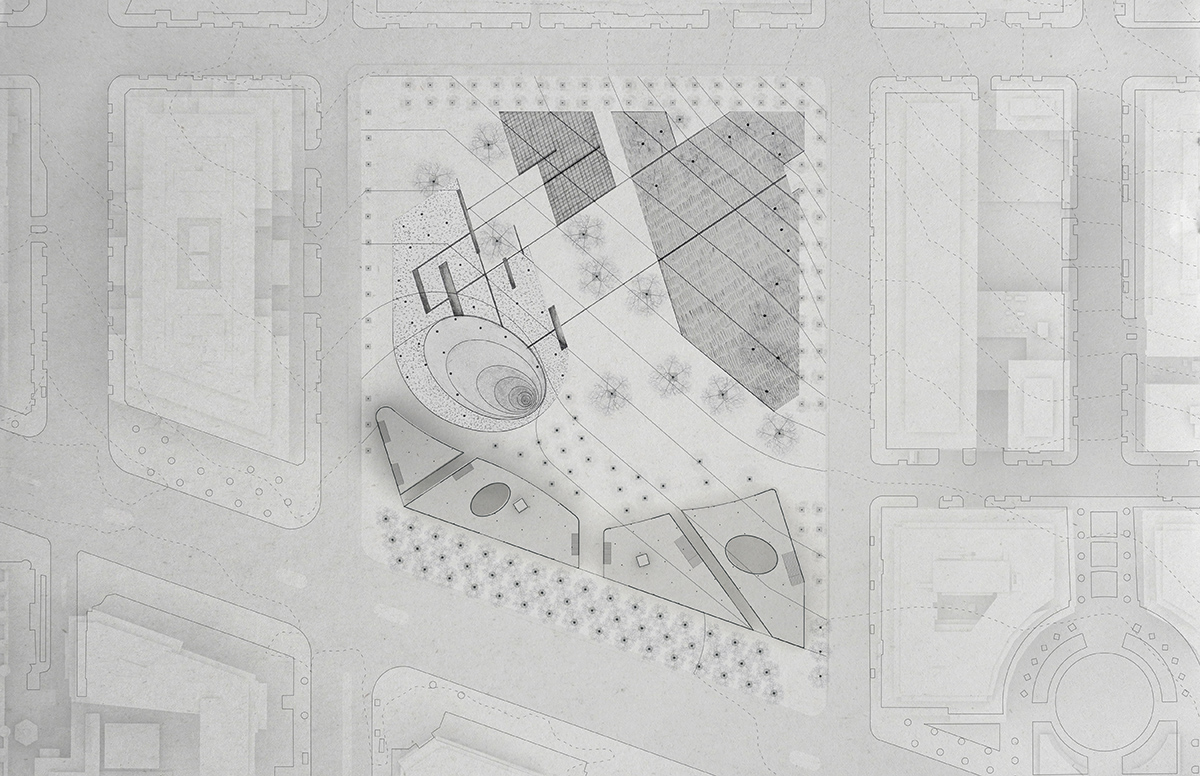

When Andrew Jackson Downing submitted his plans for the National Mall to President Fillmore in 1851 he wrote that the people of Washington D.C. would benefit from “a public museum of living trees and shrubs” displaying plants native to the region. Though Downing’s Victorian plan for an arboretum as a public park was never realized, it was the first in a series of designs for public space in the city by landscape architects that used the urban forest as a way to designate the public realm. In the spirit of past urban forest proposals for Washington D.C. by Downing, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., and Dan Kiley, this project reimagines the FBI site as a public pavilion and commons. This new space, one of the largest civic gathering spaces in the city, is not an arboretum, but rather an informal collection of past and future urban trees that define the city’s public character.

The site design was inspired by quilting and the women’s work that built D.C. in the years after emancipation. Accordingly, the site is organized in two directions. The first follows a gridded extension of the triple allée on Pennsylvania Avenue designed by Kiley in the 1960s. The second follows a patchwork of states of water through mist, runnels, wetlands, and a basin that allude to the site’s historical hydrology. The pavilion, which serves as a marketplace and exhibition space, maintains the alignment of the former FBI building on Pennsylvania Avenue. The final element is a master plan for downtown D.C. that connects Franklin Square to the commons by a meandering walk through the city, abstracting the former alignment of Goose creek and inverting the proportions of the public figure in downtown.

A Pile of CLT

Edgar Rodriguez (March II ’20)

Building upon the research developed for a suburban house, this project further deploys the interlocking wall system and the piling strategy now in the scale of an urban mid-rise building. The pile accepts chance and implies indeterminacy since replacing any unit would result in another configuration. This approach aims for the disengagement with preconceived form and advocates for a unique expression of tall buildings.

The concept of Fuzzy Modularity™ describes the systematic arrangement of standardized CLT panels throughout the design that generates a complex yet simple structure.

FOOD PARK

by Mengying Ouyang (MAUD ’20) and Shi Tang (MLA II ’21) Los Angeles County and Santa Monica have a history of agriculture, but food cultivation has been displaced largely to the Central Valley. The consequent trucking of food from the Valley and other places contributes to regional pollution and carbon imbalances, and creates food insecurity issues locally.300 Panels, 400 Cuts, 400 Bandages

Anna Goga (MArch II ’20)

300 Panels, 400 Cuts, 400 Bandages uses the full 50’ CLT blank vertically with one simple squiggle cut for each of the 300 panels. Assembled as a structural tube, the exoskeleton maximizes 5-story tall CLT Blanks and minimizes material waste. The project rethinks steel connections commonly used in mass timber construction, by re-conceptualizing the generic plate as a “bandage.” Usually hidden within the exterior wall assembly, the bandages are carefully designed, exaggerated, and exposed as compositional facade elements. Structurally and programmatically, the project explores ideas of lightness, the exchangeability of housing and office space, and the afterlife of materiality. The interior of the structural tube is comprised of four 25 meter zones with a gantry system of cranes built into each of the four ceilings. This system allows for the possibility to reassemble the interior floor plates and walls with endless variations.