Artist David Hartt on the relationship between ideology and the built environment

Montreal-born artist David Hartt uses the built environment as a tool for exploring pivotal moments, ideas and movements in history, and in doing so raises questions about postcolonial nation-building, racial identity and the ideologies that shape planning policy. In his recent work he has turned his camera on modernist ruins in Puerto Rico, the offices of an era-defining business in Chicago, and the relationship between the urban plans of Athens and Detroit. Currently assistant professor in the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Pennsylvania, Hartt has held exhibitions at the Graham Foundation, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Ahead of his talk at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, he outlines the thinking behind some of his most notable works, explaining how complex ideas are contained within these controlled glimpses of the physical environment.

Why did you choose to call your lecture “Urban Futures of the Recent Past,” the subtitle of Reyner Banham’s 1976 book, Megastructure?

I love the irony in Banham’s title. The text is a critique of a book by Justus Dahinden called Urban Structures for the Future, which is a celebration of mega-structures–vast projects like the Grands Projets in France, New Towns in Britain and those surrounding Olympics or World’s Fairs. There was an incredible optimism surrounding these projects, but they took a perverse turn in the 1970s when private developments adopted the strategies of state projects, in terms of claiming space and taking on a scale completely disproportionate to the cities they were located in.

These structures still define the majority of the built environment. In my work, I’m trying to have a conversation with these historical moments. It deals with the relationship between ideology and the built environment–I don’t say architecture, because “built environment” is more open-ended and involves shifts in scale from object, to room, to building, to block, to square, to city, to region, which I find exciting.

Your recent work in the forest (2017) focuses on Moshe Safdie’s Habitat ’67 in Montreal and another of his Habitat iterations, a failed development in Puerto Rico. What interested you about this scheme?

After the Habitat scheme in Puerto Rico was abandoned, tropical forests reclaimed it. Many of the prefab units were sold and now exist in several places around the island, clustered together in different configurations. My film features four of these, plus the main site in San Juan, presenting a dialectic between the two Habitat developments–one that’s held as a successful example of many of the tenets of modernism; the other that encapsulates many of its failures. The original scheme was built as a celebration of Canada’s independence and nationhood, while the second is in a territory that’s still under the yoke of colonialism. I am interested in why so many postcolonial countries used the vocabulary of modernism to build their institutions and how it acts as a distancing mechanism from both their vernacular and colonial architectural roots.

Your work Negative Space/The Last Poet

(2017) draws on ideas explored by Robert Rauschenberg during a journey from Long Island to Florida in 1980, as well as observations about urban sprawl by Jean Gottmann, Peter Blake and William Gibson, among others. Why did you decide to use Francis Fukuyama, who is often thought of as instrumental in the rise of neoconservatism, as the narrator of the images you depict?

I went to Fukuyama because I was interested in the fact that [political opinion] has become so polarized. In one sense, the work functions as a way of bridging that gap and finding common ground by addressing a prominent figure with a deep sense of historical perspective, but one who is very much on the other side of the political spectrum from me.

In an opinion piece in the Guardian in 2007, Fukuyama characterized the EU as the closest we have to his idea of the “end of history.” His argument was that liberal democracy and free market economics are symptomatic of the final stages of human development. In many ways the United States is similar, in terms of being a contiguous geographic expanse. I traveled along a similar route to the one Rauschenberg had taken. He took photos using what was at the time an innovative technology–a new Canon SLR. I thought about how I might look at the same landscape with the tools I have available today, and decided on using a drone, which immediately gives a different perspective.

Again, I’m using the built environment as a proxy to address other broader or historical concerns, to annex the ideas other contributors and researchers had in mythologizing space. I was much more interested in the political landscape than the actual physical landscape. This was a way of situating and contextualizing the work and trying to address the backdrop within which our discourse around the emergence of the far right is taking place.

Photography courtesy of the artist, the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Corbett vs. Dempsey and David Nolan Gallery.

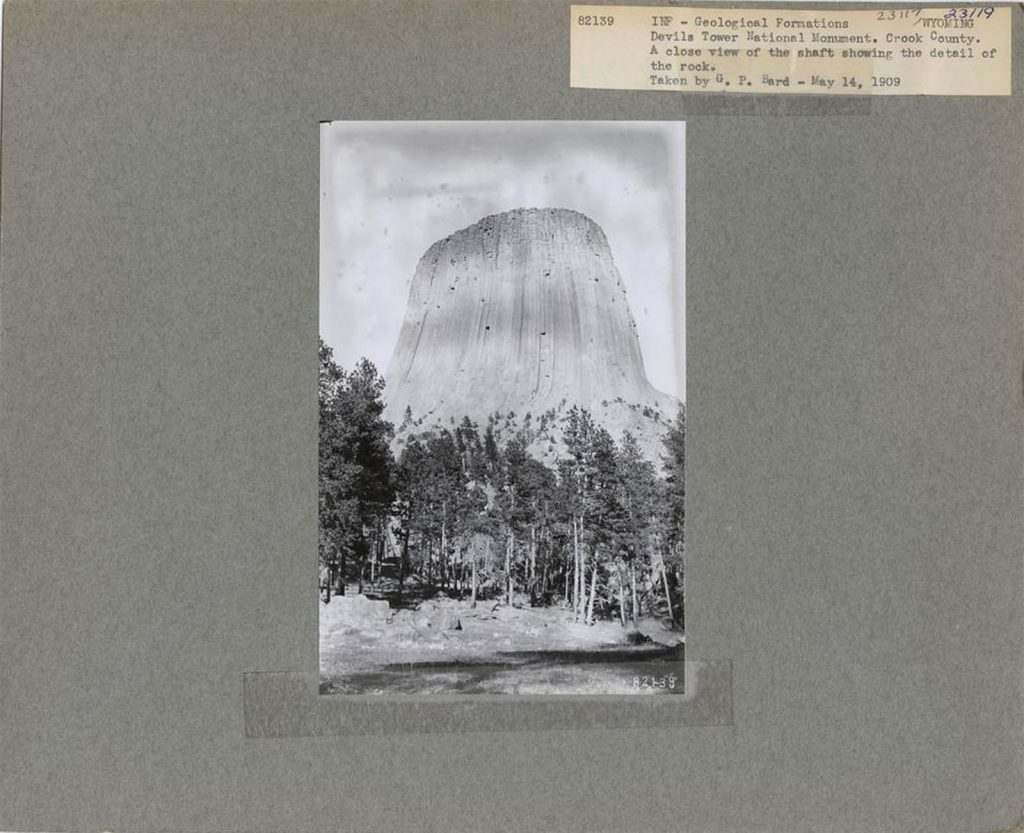

Mountains and the Rise of Landscape exhibition reconsiders what it means to see and experience mountains

The totemic nature of mountains creates a paradox: Their overwhelming size makes them an unavoidable and seemingly understandable part of our image of the earth, and yet this very grandness causes them to resist total visibility and, with that, any notion of comprehension. Mountains’ terrifying splendor, which conjures an attraction not unlike our long-held fascination with the “far side of the moon,” could in turn be credited with the persistent urge to represent them—as painters, writers, and others have done for centuries. But how do you even measure a single mountain, for example? Instead of starting from sea level, why not begin at the earth’s core, closer to the geological forces which created it? What constitutes a mountain range, and what is lost and gained through depicting them as a stenciled line of peaks, as was common in 19th century guidebooks? Such drawings neglect mountains’ complex interior lives—though the tunnels bored through them for roads, military purposes, and mineral excavation raise the question whether many mountains can still be considered natural at all. And the even greater—and constant—violence against nature by humans that defines the Anthropocene, including the destruction of glaciers at an ever-increasing pace, may have made depicting the natural world through any static form of representation too great a lie to accept any longer.

The exhibition Mountains and the Rise of Landscape, curated by Michael Jakob, asks these and a panoply of related questions, not through an impulse to neatly define the object we call a “mountain” but rather to problematize the ways in which these awesome structures have long been incorrectly reduced to a univocal definition. In seven distinct sections, which highlight numerous modes of representation including maps and other models, scientific instruments, drawings, photographs, film, sculpture, and even the soundscape of a melting glacier, the exhibition charts the evolution of mountains in the cultural imagination and, through this, the broader relationship between humans and the environment.

“Historically, and especially in Europe for over one thousand years, mountains had been largely invisible because nature was interpreted as negative—the realm of the devil, the site of the Flood and original sin,” explains Jakob. “Then in the 18th century, scientists, mathematicians, travelers, and artists changed the interpretation. In part through measurement, modeling, and reliefs, mountains were no longer seen as disgusting and disgraceful; they became objects of love and reverence because people discovered what was sold to them as a miracle of the sublime forms of nature.”

Foundational to this sense of sublimity and the philosophical and aesthetic shift it occasioned was the “serpentine line” praised by William Hogarth in The Analysis of Beauty (1753). In this seminal work, the English artist and writer argues that the S-shaped line—an inherent abstraction of a mountain chain’s undulating peaks—“leads the eye in a pleasing manner along the continuity of its variety.”

Co-curator Pablo Pérez-Ramos plays with this concept in the most monumental facet of the exhibition: a 100-foot-long wall featuring a Sol Le Witt–like mural in which the profiles of thirteen mountain ranges generated using various digital mapping tools were drawn by hand at a scale of 1:150,000. “We’re looking at mountains at a scale at which they’re normally not looked at—in relation to the earth as a whole. The panoramas are so long that they’re not able to be horizontal anymore but curved, to represent the curvature of the earth,” says Pérez-Ramos. “The profiles are in a way indexes of the history of those mountains, and this exercise can tell us how different geological forces construct the surface of the earth.”

Humans, too, alter the earth’s skin and in turn elicit changing perspectives on mountains. Consider grandiose feats of engineering such as dams. Like the “false mountains” featured in the exhibition such as pyramids, these sites can diminish mountains in our collective imagination by virtue of their serving as a beacon of human development, especially when built near or even on mountains. “You can read this entire exhibition as related to the Anthropocene, and highlighting these processes highlights the fragility of different perspectives of our sense of mountains,” details Jakob.

Emblematic of this vulnerability of perspective is the work of photographer Yao Lu, whose images appear in co-curator Edward Eigen’s intervention How to Model a Mountain in the Frances Loeb Library, which explores aesthetic, philosophical, and other thematic approaches to mountains throughout history. At first glance, Lu’s photographs appear as classical Chinese landscape paintings, but upon closer investigation, the grand structures reveal themselves as another kind of “false mountain”: piles of trash.

This illusion and subsequent realization illustrates what Eigen considers one of the entire exhibition’s chief virtues. “Mountains are so ‘there’ that even if we have positive or negative associations with them, we think they’re just mountains,” he says. “This exhibit forces people to reconsider what it means to see and experience mountains, to defamiliarize them.”

Beate Hølmebakk discusses her paper projects and rejecting the dominance of user-friendly architecture

In 2004, Norwegian architect Beate Hølmebakk co-founded Manthey Kula with Per Tamsen, and the practice has since become known for small but beguiling architectural interventions that play with form and context in unexpected ways. From a heavy steel restroom overlooking Norway’s scenic Moskenes Island, to a transparent ferry port with a distinctive, U-shaped roof–both of which were nominated for the Mies van der Rohe European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture–their work transforms humble briefs into arresting shapes uniquely suited to their site and purpose.

A significant part of Beate’s practice are her “paper projects”, works that are deeply considered but never intended to be built. In Virginia, a series of houses were conceived around the lives of four female literary characters; in Archipelago, the stories of five people living in isolation on remote islands were used to develop a set of architectural forms. Through these speculative explorations, Manthey Kula pushes the boundaries of architecture as a medium for exploring fictional states of mind, body and form.

Today, Holmebakk is a professor of form, theory and history at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Ahead of her lecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, she discusses her philosophy and approach to both these types of projects, explaining how she measures the success of an idea and why architecture needs to “dare to have character”.

How do the two elements of your practice, the built and unbuilt works, relate to each other?

With the built work, we’re concerned with the site: how the building can make it more interesting, solve its problems or foreground its most beautiful elements. The unbuilt projects don’t have a site, so the internal story becomes the context. There’s always a narrative and an existential theme in the paper projects, which the architecture is built around. Whether a project is ultimately built or unbuilt, we’re interested in sculptural forms that have character. What ignites the form varies, but how we develop it is similar; it’s like the difference between prose and poetry.

Do you think of architecture as an artistic medium?

Absolutely. When we work as architects, we have a lot of measurable constraints and we’re trained to be logical in the way we develop a project, to show there’s a reason for our choices. But it’s the mix of personal, irrational elements that dictates if a project is going to be this or that. In the end, it’s about feeling trusted and believing in your own ideas.

At its best, I think architecture is a state of mind. There’s something about the experience of space that has been with us since we were small–a basic understanding that has to do with our personal story. I believe that’s an important factor in the way we work: the search for something eternal in our experience that we’re trying to recreate. When you enter a building or a space that is well made, it’s an existential experience.

Without rational parameters–for example with your paper works–how do you measure success?

In our paper works we create self-imposed constraints; it’s hard to develop anything without any limitations. In the beginning, it was more about trying to find a theme that could be dealt with architecturally, whether it was the relationship between people or between inside and outside. With the Virginia project, the architecture developed from personal interpretations of literary texts. Later on, for example with the Archipelago project, we imposed specific, almost mathematical constraints–for example, scales and measurements that were in use during the time when these historical protagonists lived.

You’ve said in the past that you don’t particularly like terms such as “user friendly” or “humane” as architectural aspirations. Why is that?

If you want a project that people can relate to, it has to have a core that people can agree or disagree with. It has to dare to have character. I think it would be a mistake to overlook the complexities that exist in our discipline and attempt to make architecture digestible for everyone. There are so many nuances in the world, so if one is only seeking a norm for what is “humane” or “user-friendly” in architecture, that would be incredibly boring.

Images courtesy Manthey Kula.

Dean’s year in review: Highlights from 2016–2017

Dear GSD Alumni and Friends,

As the spring semester culminates in an exciting range of studios and thesis reviews, and as the next class of graduates prepares to embark on new careers, launch new ventures, and drive new lines of research, I write to share highlights of the important work produced at the GSD over the past year.

I am also pleased to report that in the most recent DesignIntelligence ranking of America’s best architecture and landscape architecture programs, the GSD maintained its position at the top. As you know, the results of these rankings are referenced by prospective students and potential employers of our graduates, and as a result they have a material effect on the School and its community. The surveys for the next rankings in architecture and landscape architecture are now open, so if you are in a leadership or hiring position in a design-related field, I encourage you to submit a response and share your experience by the deadline, which is May 26th.

Our current ranking, I am proud to say, continues to be reflected in the outstanding quality of the School’s output. Its excellence and integrity are grounded in the School’s values and its direct engagement with the ethical dimension of what we do. As a School, we are committed to the transformative power of design and its capacity to create just and equitable cities. It is my pleasure to share with you a summary of what we have accomplished this year toward that end, and what we look forward to achieving in the semesters and years ahead.

A Leader on the Future of the City

Across departments, the GSD extended its deep analysis of global urbanization and the multitude of its effects. Indeed, we aspire to be the world’s intellectual leader on the future of the city, and we continue to develop and refine new studios, public programs, and a host of other research initiatives to make progress on this ambition.

In studio work completed over the past year, students and faculty investigated a series of specific urban contexts and produced substantive proposals aimed at bettering the lives of their residents. Our studios included site visits to 37 cities in the U.S. and around the world. In conjunction with AECOM, we organized a series of option studios themed geographically around Southeast Asia. In spring 2016, the series studied Jakarta, and this spring we turned our focus to Kuala Lumpur. The third installment, scheduled for next fall, will focus on Manila. In the Department of Landscape Architecture, faculty and students designed innovative renewal solutions for a section of Houston’s Buffalo Bayou. Option studios in the Department of Urban Planning and Design covered specific sites from Savannah, Georgia, to Sao Paulo, Brazil, to Palava City in Mumbai, India, and topics ranging from urban ecology to affordable housing and questions of shelter and displacement.

Working side-by-side with city leaders and local communities is an important part of equipping students with the skill and insight to make an immediate and positive impact on the world. This year, we hosted an impressive roster of policy makers and city leaders, who contributed to the School’s pedagogy as review panelists, speakers, and design critics. Among them, we welcomed the mayors of three major cities to address students and faculty: Mexico City Mayor Miguel Ángel Mancera , Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, and Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh . In addition, Stephen Ross and Richard Rogers , among others, spoke as part of our public program, and we organized conferences and exhibitions on Tokyo and Barcelona, examining these cities as case studies in designing the future city. Taken together, all of this activity provided a rich combination of formats, each of which connected to the School’s core pedagogy in a unique way, supplementing our studios and seminars with exposure to decision-making in urban policy at the highest levels.

Following the talk by Richard Rogers at the GSD, we launched a new fellowship program based in London at Rogers’ Wimbledon House, a home he designed in 1968 and that he and his wife, the celebrated chef Ruthie Rogers, donated to the GSD for this purpose. The fellowship serves as an international platform to convene experts and practitioners from a broad range of disciplines whose work is focused on the built environment and its capacity to advance the quality of human life. In March, we welcomed the inaugural fellows at the house. Located near some of the world’s finest resources for research in urbanism, the program represents both an international extension of the GSD’s physical footprint and a symbol of the School’s commitment to engaging issues faced by cities globally.

While the purview of the School’s work is global, it is important, however, to emphasize that our focus on the future of the city is buttressed by a clear framework for engagement with local communities, starting with our own here in Cambridge and neighboring Allston and Boston. Toward that end, a series of studios proposed solutions for Cambridge’s Central Square neighborhood and Boston’s Harbor Islands. In partnership with Harvard’s central administration, the GSD also led a design-build competition for a public commons in neighboring Allston , offering our students an opportunity to undertake a built project while considering its impact on the neighborhood. Throughout our work in Allston and other communities around Boston and Cambridge, close communication with residents remains an essential part of the design process.

Amid this constellation of new and developing projects, the Office for Urbanization extended its research on Miami Beach, and together with Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health we are excited to enroll the first class in a new joint degree in health and urbanization. As the work we produce through our portfolio of city-focused initiatives continues to grow, we also look forward to formalizing a broad, institutional platform—Future of the American City—which will give institutional structure and support to the School’s energies focused on the future of urban America. I look forward to sharing further developments as we make progress.

Design Research for a Better World

As many of you know, the GSD’s commitment to design research has grown substantially in recent years. We aim to be deliberate and constructive with this growth, asking questions about which issues lend themselves best to our interdisciplinary approach, and how we can maximize opportunities for students and faculty alike.

Alongside the tradition of individual faculty research, our option studios have emerged as domains of collaborative investigation around specific themes, geographies, and strategies. We have been able to offer option studios that vary in scale, from the streetscape to the territorial; that engage with industry, technique, and social justice; and that examine sites located in the far reaches of the globe as well as our own local communities. Examples of this include the AECOM studios and a three-part studio series in collaboration with Knoll, examining professional work environments. The comprehensive approach of the option studio model is unmatched by any other school, and it is key in preparing our students as leaders and shapers of the built environment.

Innovation remains a cornerstone of our research agenda as well, and some of our most deeply interdisciplinary research has been focused on creating entirely new forms of knowledge. Soon, the Center for Green Buildings and Cities will break ground on its “House Zero,” an experiment in transforming existing buildings into energy-efficient, energy-producing structures. Our partnership with Peking University through the Ecological Urbanism Collaboration has continued with a series of research and summer study projects. Our Master in Design Engineering (MDE) program, offered in collaboration with Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, concluded its inaugural year with a series of design-driven innovations in global food systems. We also named the first two recipients of the John E. (Jack) Irving Innovation Fellowship, a new program intended to support outstanding, cutting-edge research conducted by select recent graduates.

Dynamic Public Programming

The GSD’s public programs and exhibitions continue to offer opportunities to bring new ideas from a wide variety of disciplines into the life of the School, and they also offered valuable community-building moments. Talks by artists Christo and Jeff Koons and writer Jonathan Franzen—all made possible by the Rouse Visiting Artist Program—brought excitement and creative energy to Gund. They reaffirmed the GSD as a destination for rich conversations at the intersection of the humanities and design, both for the GSD community and for students and faculty across Harvard. This March, we held a special celebration for I.M. Pei (MArch ’46), marking his centennial birthday with personal reflections given by Henry Cobb (AB ’47, MArch ’49), Bart Voorsanger (MArch ’64), and others. This fall, we will host a conference intended to produce some of the first critical engagements with Pei’s prodigious career.

Our roster of talks and lectures made room for serious pedagogical discourse as well. Rem Koolhaas presented in October, touching on architecture’s role in the global political climate. This spring, we convened an exciting panel of experts, including Harvard Business School’s Rajiv Lal, Warby Parker CEO Neil Blumenthal, and DACRA CEO and President Craig Robins, for a discussion on the relationship between the physical and digital retail space. While much of our learning takes place in the classroom and in the studio, opportunities to hear from such leaders visiting from outside the School create unique learning moments that supplement our core pedagogy.

Our exhibition program extends this scope of interdisciplinarity. Exhibitions on contemporary Chinese architecture, Barcelona’s urban development, and the work of Atelier Bow-Wow reflect the GSD’s global focus. We were especially honored to mount an exhibition in collaboration with Harold Koda (MLA ’00), former Curator in Chief of the Anna Wintour Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and landscape architect Ken Smith (MLA ’86). The exhibition, “Designing Planes and Seams,” explored the shared concerns of landscape architecture and clothing design, how surface materials and process engage with time, space, structure, and the environment. The exhibition serves as a poignant example of how much we stand to gain from thinking across fields and representing our work in dynamic and immersive ways. It represents a commitment to design, creativity, and imagination shared by our students as well, a commitment that was on full display in the ninth edition of our Platform exhibition. In organizing the show, the student-faculty curatorial team invoked the concept of the “still life” as a device to arrange compositional groupings of student work from across the School. Establishing spatial juxtapositions between projects from across disciplines, the exhibition made visible a multiplicity of contexts and perspectives. Through such relational techniques and exercises of the imagination, new ideas emerge.

Looking Forward

In closing, I want to share a few more exciting programs and initiatives coming up next year and beyond. In the fall, many GSD faculty and alumni will be participating in the second iteration of the Chicago Architecture Biennial , which will be curated by GSD alumni Sharon Johnston (MArch ’95) and Mark Lee (MArch ’95). As we look to the future of online education, we are also considering how design pedagogy might be reshaped in the digital era, calling on the expertise of our faculty who teach in both the degree and executive education programs. This year we took a bold step in this direction with Michael Hays’s online course, “The Architectural Imagination ,” which immediately became one of the most sought after courses at HarvardX, and which I encourage you to check out.

We are exploring possibilities for expanding our physical footprint to better respond to the School’s commitment to innovative teaching and research. Expansion will also enable us to address the spatial demands of our increased scope of activity and growing community.

Our faculty hiring has kept pace with our expanding student body. While the work of several search committees is still in progress, we have finalized appointments or promotions of 11 faculty. A number of exciting appointments are in the pipeline, about which we will send out a separate announcement this fall.

A few months from now, we will welcome another promising new class of students to Cambridge. Our most recent admissions cycle marks another successful round of recruitment with an exceptionally high yield rate. Our international yield rate remains very high despite widespread anxiety about U.S. immigration, a testament to the quality of our work and the impact our faculty, students, and alumni are making in the world.

As always, I look forward to visiting with many of you in the next year at a reunion on October 13–14 for classes ending in 2’s and 7’s, or at one of our many alumni events. It was a pleasure to see over 100 alumni visit Gund Hall last fall to celebrate their 5th to 50th reunions. In April, Martin Bechthold (DDes ’01) and the DDes program welcomed over a quarter of the 180 DDes alumni for the program’s 30th anniversary. With one year remaining for the Grounded Visionaries campaign, fundraising for student financial aid and fellowships remains a high priority for the School. Such support is crucial to the GSD’s ability to continue attracting the most talented students from around the world.

If you are in the Boston area next fall, I encourage you to visit Gund Hall and join the conversation at one of our public lectures. I am grateful for your committed support of the School and wish you an enjoyable and productive summer.

Best regards,

Mohsen Mostafavi

A Community Message from Dean Mohsen Mostafavi

Dear GSD Community,

On Friday afternoon President Trump signed an executive order that has closed the United States’ borders to refugees and citizens of seven countries with predominantly Muslim populations: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Implemented immediately, the order has generated confusion and chaos around its reach and its full ramifications. We have been hearing news about travelers with legitimate visas and green cards being prevented from boarding planes or having been detained at airports. Among you are students, faculty, and staff who are or will be directly affected, and others who have friends and family who will in some way be affected as well.

Let me be clear that the intolerance and prejudice signaled by this action cut against the core values that the GSD stands for. Its spirit runs counter to our collective commitment to inclusion and to cultivating a diversity of people, ideas, and perspectives, the necessary ingredients of healthy and productive discourse and responsible citizenship. While we must expect even more significant changes and greater turbulence from the political sphere, we must be strong in standing together and must not waver from the core values that unite us as a community.

Toward that end, we will convene a town hall meeting to discuss how we can support each other through this challenging moment, and how we can mobilize to effect positive change amid the divisiveness and discrimination that have come to define our current political environment. I am eager to hear and participate in a dialogue about everyone’s ideas. You can expect to receive more details this week.

Many of you will have questions about the effects of Friday’s order and how they relate to you or your loved ones. A federal judge has now blocked part of the order, a principled response against this unjust action. The school’s administration is working hard to understand specifically what impact the order will have, and more information will be shared as soon as possible. In the meantime, students who have concerns that require immediate attention should contact our Dean of Students. Faculty with visa concerns should contact our Assistant Dean for Faculty Affairs. I also encourage you to talk to each other, share what you know, and lend a helping hand to anyone who needs it. In taking care of each other, we infuse our creative efforts with the respect, hospitality, and generosity inherent to the kind of just world we aspire to build.

Mohsen

Mohsen Mostafavi is Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design.

Dean Mohsen Mostafavi’s Post-Election Message

Dear GSD Community,

The recent presidential election, if nothing else, has been a wakeup call not just for the nation but for the design profession at large. The debates have unraveled the extreme differences and disparities between communities and geographies—between the rich and the poor, the urban and the rural, the global and the local.

Sadly, the prevalent and proto-nationalist posture of much of the propaganda has found a convenient way to blame the “other” for everything that is wrong with our society. This clever sleight of hand does disservice to the disenfranchised, who have the right to homes, schools, work places, public spaces, and livable communities. These are just some of the necessary elements of a good and honorable life that require the talents of designers.

The GSD’s diverse and international community is and remains vigilant against all forms of injustice. We must make sure that our creative efforts towards the making of a just and better world are more effective and consequential than ever before.

Our belief in the transformative power of knowledge and learning is one of our defining characteristics. This is the time for positive and united action. We will not only be shaped by these actions but will be judged by them too.

Long live kindness and the powers of the imagination.

Mohsen

Mohsen Mostafavi is Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design.

Frank Gehry first architect to receive Harvard Arts Medal

Architect Frank Gehry has been named the recipient of the 2016 Harvard Arts Medal , which will be awarded by Harvard University President Drew Gilpin Faust at a ceremony on Thursday, April 28. The ceremony, presented by the Office for the Arts at Harvard and the Board of Overseers of Harvard College, will include a discussion with Gehry moderated by actor John Lithgow, who is host of the event.

This marks the first time that the Harvard Arts Medal has been awarded to an architect.

“Frank Gehry is a true original, a visionary artist whose work has revolutionized architecture and place-making in the 21st century,” said Lithgow. “He’s the first architect to receive the Arts Medal, and Harvard looks forward to celebrating his extraordinary achievements and risk-taking spirit.”

Gehry is the design principal of Frank O. Gehry & Associates Inc., which he founded in 1962. Born in Toronto, he studied urban planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design after receiving a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the University of Southern California. He has produced remarkable public and private buildings in America, Europe, and Asia, that powerfully express the dynamism of contemporary urban life, and he is celebrated for bold designs and dazzling metal structures. Among his many honors are the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the National Medal of Arts, the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal, and the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Royal Gold Medal for Architecture.

To learn more, please read Harvard Magazine’s coverage of the 2016 award.

New Office for Urbanization focuses on research projects attendant to the contemporary city

The Harvard Graduate School of Design announces the formation of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design Office for Urbanization, a trans-disciplinary initiative that will focus the intellectual and practical capabilities of the School on a range of applied design research projects attendant to the contemporary city. The Office will be led by founding director Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture.

The Office for Urbanization will build upon the GSD’s legacy of innovation in design research to address societal conditions associated with contemporary urbanization. Engaging faculty from the School’s three departments, the Office will draw upon the range of disciplinary and professional knowledge embodied in the GSD’s research advancement initiatives and design labs to extend the School’s impact on the future of cities around the world. Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design, describes the initiative as “a continuation of the GSD’s historic leadership in applied project-based design research, and an exciting new initiative reconfirming the School’s commitment to impactful societal engagement through design. The Office will work to shorten the distance between innovation in design research and impact in the world.”

The Office will provide a venue for the advancement of knowledge on the role of design research in relation to the social and environmental challenges associated with ongoing urbanization. Collaborating with the Center for Green Buildings and Design, the Joint Center for Housing Studies, and Executive Education, and engaging government agencies, non-government organizations, philanthropic institutions, and community leadership, the Office will articulate and evaluate various scenarios for urbanization through a number of agendas for design research.

Global in its purview, the Office will engage partners on a diverse array of sites and subjects domestically and internationally. Its inaugural project will focus on municipal response to sea level in partnership with the City of Miami Beach. “This foundational project of the Office for Urbanization will examine the implications of rising sea levels and increased storm events on the economy and ecology, infrastructure and identity of Miami Beach in relation to its metropolitan and regional contexts,” Waldheim says. “The study will develop design strategies and scenarios to mitigate present threats and to anticipate future potentials facing one of the world’s most recognizable and singular cultural landscapes.”

A meditation on race, design, and social justice: the Black in Design conference

Recent events in Ferguson, Staten Island, Baltimore, and elsewhere have positioned racial inequality as a prominent point of debate, and a series of lenses—socioeconomics, ethics, and the law, among others—have been applied to ensuing dialogue. Questions of design, urban planning, and the built environment loom beneath these concerns, and designers and planners have been considering their roles in addressing them.

At the same time, though, critics argue that the prejudices and priorities inherent to design as a field can breed the disparities that find form in the nation’s buildings, neighborhoods, and cities. Eyeing these and other questions around race, inequality, and design, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s (GSD) African American Student Union (AASU) orchestrated an unprecedented event at Harvard: the Black in Design Conference, held at the GSD on October 9 and 10.

The conference harmonized with the AASU’s broader goal of fostering a network and community that actively promotes the interest of the GSD’s African-American students and alumni. The AASU was founded in 2012 by Jean Lauer (LF ’12) and Tracie Curry (MLA ’12) and is currently led by president Dana McKinney (MArch/MUP ’17).

“We felt that there is an unfortunate lack of discourse around the accomplishments of black designers and the social effects of design on the black community at the GSD and in design academia altogether,” says Cara Michell (MUP ’16), AASU member and one of the conference co-chairs. “We considered the Black Lives Matter movement a call to action for us as designers to begin taking responsibility for widespread and historically rooted equity issues within our own field and in society at large.”

The GSD has recently made a priority of discussing and addressing these dynamics. Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design Mohsen Mostafavi introduced the Dean’s Diversity Initiative in 2008 with the goal of tasking GSD faculty, staff, students, and alumni with increasing the number of underrepresented minorities within the GSD community and maintaining an inclusive environment that encourages an active and effective exchange of views. Meanwhile, programs, conferences, and general dialogue around issues of social justice and inequality have germinated throughout the school, including last April’s panel Informing Justice: A Conversation about the Role of Design in Building Equitable Communities .

Yet, as Mostafavi noted in his opening address at Black in Design, the global dynamics between race, space, and design are persistent—evidenced by the fact that, 20 years ago, he found himself in the GSD’s Piper Auditorium leading a conference titled Denaturalized Urbanity: Race, Gender, and Ethnicity in the Landscape of the American City.

“The relationship between race and space, the way in which one could say the racialization of space is becoming more extreme, is continuing,” Mostafavi told the Friday evening crowd. “These issues have remained absolutely pertinent.”

A slow-build project

The AASU started planning Black in Design two years ago, ultimately defining its goals categorically: recognizing the contributions that African descendents have made to design fields; reclaiming the histories of underrepresented groups in design pedagogy; focusing designers toward their roles in bettering the built environment; and ingraining in designers a sense of compassion, as well as the responsibility to build just and equitable spaces at every scale.

The group began official planning discussions in spring 2014. Along with Michell, Courtney Sharpe (MUP ’16) co-chaired the conference and its planning. This past spring and summer were dedicated to finalizing an invitation list, conducting sponsorship outreach, and producing a website and general marketing content.

Among the student portraits gathered for marketing content, the group was drawn to one in particular, which would become the conference’s primary branding visual: a black-and-white photograph of Allison Green (MUP ’15) with a black bar over her eyes.

“In my mind, that black bar over the eyes plays with the notion, and very common experience at the GSD, of being the ‘token’ black person in the room,” says Michell. “It evokes feeling as though your unique identity has been removed and replaced by the blunt fact of being black—with all the stereotypes, burdens, and so forth that come with it.”

Scalar, immersive conversations

Friday evening’s opening panel was moderated by K. Michael Hays, Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, and examined design pedagogy. In his opening remarks, Hays drew attention to the concept of the white spatial imaginary, a dynamic that, he noted, has prevented some from understanding fundamental features of the social spaces in which citizens live.

“The white spatial imaginary produces the kind of defensive localism that dominates decisions about public interventions and how services are distributed, and of course it produces that privatism that sometimes turns hostile,” Hays said.

“If we can think about teaching the techniques and practices and forms of design that distribute space and time, that distribute subjects and objects, with [the white spatial imaginary] in mind,” Hays continued, “then we can pedagogically have very real effect on place-related opportunities.”

Saturday’s panels and sessions built upward in scale. The first panel focused on buildings, followed by sessions on the neighborhood, the city, and the region.

“The scalar structure of Saturday’s panels was designed with the intention that the format would reinforce cross-disciplinary intersectionality and promote discourse,” says AASU president McKinney. “Using this approach, we hoped to also demonstrate the scalar fluidity of varying design practices.”

The AASU embedded a variety of cultural, sensorial experiences into the weekend’s events. Yoga instructor Maya Breuer opened Saturday’s events with a series of yoga exercises that evoked introspection and openness.

“Maya created an overwhelming sense of hope and togetherness that permeated the room during every moment of the conference,” Michell says. “She set a tone for the day with joy and hope.”

Saturday’s lunch was a thoughtfully curated event, designed by chef and food-justice activist Bryant Terry and chef and food consultant Didi Emmons. After a discussion of the cultural significance and legacy of soul food, and whether it can or should be healthy, the meal provoked dialogue on public health and on questions of where food comes from, who has a hand in its production, whom it serves, and what is its cultural importance.

Later that day, an interlude featured Latin American poet Jenesis Fonseca reciting an original poem and leading the audience through a rendition of Janelle Monae’s protest song “Hell You Talmbout,” which recites the names of victims of police violence. The audience also heard the Kuumba Singers of Harvard College , a historically African-American chorus founded in 1970, sing a series of traditional spirituals as well as “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” often called “the Black National Anthem.”

Holistically, these programmatic elements worked to elevate the conference to an immersion in and meditation on the intersectionality of culture, design, and social justice, with an eye toward the work that needs to be done.

“We hope that the conference incites increased interest in and appreciation of diversity such that more underrepresented minorities choose and are invited to join the GSD community as students, faculty and staff,” McKinney says. “The GSD belongs to the broader Harvard community and stands to inspire other design schools to better promote diversity, inclusion, and a discourse of social justice.”

The Black in Design conference was organized by the Harvard GSD African American Student Union with support from the Joint Center for Housing Studies, Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Loeb Fellowship at Harvard GSD, the Dean’s Diversity Initiative at Harvard GSD, H-OAP, the Ash Center for Democratic Governance & Innovation (HKS), and the Harvard Art Museums.

Bradley Cantrell appointed Director of Master of Landscape Architecture Program

The Harvard Graduate School of Design announces the appointment of Bradley Cantrell (MLA ‘03) as director of the Master of Landscape Architecture program, commencing immediately.

Cantrell was appointed associate professor of landscape architecture at the GSD last July. His appointment as director of the Master of Landscape Architecture program follows the appointment of Anita Berrizbeitia (MLA ‘87) as chair of the department, announced earlier this summer.

Cantrell’s work as a landscape architect and scholar focuses on the role of computation and media in environmental and ecological design. He served as the 2013–2014 recipient of the Garden Club of America Rome Prize Fellow at the American Academy in Rome, and as Director and Associate Professor at Louisiana State University Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture. He has also taught at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Cantrell’s research and teaching focuses on digital film, simulation, and modeling techniques to represent landscape form, process, and phenomenology. His expertise in digital representation ranges from improving the workflow of digital media in the design process to providing a methodology for deconstructing landscape through compositing and film editing techniques.

Cantrell received his bachelor of science in landscape architecture from the University of Kentucky and his master of landscape architecture from the GSD.