October 2019 News Roundup

Sai Balakrishnan’s new book Shareholder Cities: Land Transformations Along Urban Corridors in India from the University of Pennsylvania Press will be released on November 1st. A related panel discussion moderated by Rahul Mehrotra will take place on November 5th at the Harvard South Asia Institute.

Diane Davis was a guest speaker on the topic of resilience at the 2019 Conscious Cities Festival at the Pratt Institute in New York, hosted by The Centre for Conscious Design. Davis, along with Maria Atuesta (Ph.D. candidate), recently published a research paper supported by the Joint Center for Housing Studies titled “Progressive Politics and Inclusive Social Housing: Enablers and Barriers to Transformative Change in Bogota.”

Daniel D’Oca and his firm, Interboro Partners, designed a seventeen-acre natural playscape for the City of St. Louis’ Forest Park . The city just broke ground on the playscape and it is planned to open next summer.

Christopher Herbert will be giving the opening remarks at an upcoming event, “Housing and Innovation: Lessons from the Ivory Prize,” hosted by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies on November 15th. Innovative strategies on how to overcome challenges of affordable housing will be discussed.

Bing Wang has been appointed as Advisor of Master Planning by the Royal Commission of Al Ula in Saudi Arabia . Also, Wang, along with former MDes student Van-Tuong Nguyen, gave a talk titled “Co-Living in the Sharing Economy,” which was sponsored by the Joint Center for Housing Studies.

The Harvard Gazette’s interview with Tom Hollister and Katie Lapp explored Harvard’s positive annual financial report and touted the success and promise of Executive Education across the University. While growth of Executive Education university-wide is at 12%, the GSD’s Executive Education grew at more than double that rate last year, at 27%.

Jorge Silvetti and Rodolfo Machado are awarded the 2019 Druker Award & Lecture

. Silvetti and Machado will be receiving and giving respectively, at the Boston Public Library on Saturday November 9, 2019. The Griffin Award is presented annually to a speaker or speakers who has or have made outstanding and important contributions to the world of urban art and architecture. This award is a reproduction of the historic copper griffins gracing the roofline of the Boston Public Library’s iconic McKim Building (1895), designed by acclaimed architect Charles Follen McKim.

Toni Griffin is awarded Social Justice Design Award by the Institute for Public Architecture . IPA uses design to challenge social and physical inequities in the city and believes in a future in which design is used as tool for facilitating social justice and the public has a voice in all decisions that shape our built environment. Griffin will join two other honorees, Deputy Mayor Vicki Been and artist Mary Miss at the IPA’s 7th Fall Fete on November 13 at JACK Studios.

Jesse Keenan leads and serves as Editor of the publication Community Development Innovation Review, “Strategies to Address Climate Change Risk in Low- and Moderate-income Communities” published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. It was discussed as part of a larger conversation on the New York Times regarding how climate change causes financial risks and their ramifications. The conversation continues on a Bloomberg article , with alarming statistics. In other research, Keenan’s study of the U.S cities identifies Duluth, Minnesota as a well-situated climate sanctuary, which was further discussed on Reuters and Inverse . In a Washington Post article , Keenan made a comment about the threat of water rising to stadiums along the coast and their supporting transportation and infrastructure.

Student groups are active at the GSD. A new student group: Asian Pacific Islander American (APIA) , recently forms for the community. Harvard Graduate Students Union-UAW , a larger Harvard University-wide published a zine “What Will It Take?” on Strike Authorization Vote.

The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) announced their 2019 student awards . Six awards went to GSD students in all categories. The Student Awards will be presented at the 2019 ASLA Conference on Landscape Architecture in San Diego, November 15-18.

Panharith Ean (MArch I ’20) was selected as one of the top five finalists in the Samsung Mobile Design Competition , a global context calls for the next paradigm of mobile wallpaper, incorporating interactivity and contextual awareness. Ean recently presented his design in London before a jury panel.

“Style Worry or #FOMO” curated by Max Kuo is exhibited on the Experiments Wall, displaying works produced for a seminar under the same name. The exhibition makes explicit the wide formal variety of architectural work that is not only coursing through GSD but also a widespread condition of our contemporary moment. This exhibition also underscores disciplinary concerns of architecture where research and scrutiny of how to make form is of primary concern.

“Landscape: A Human Centered Notion of Existence” by Shikun Zhu (MDes ’20) is exhibited on the Student Forum Exhibition Wall, the second floor of Gund Hall. It exhibits a series for photography records a range of landscape as well as existence, from our artificial objects in nature to our presence in nature and urban environment.

Love in a Mist—or Devil in a Bush? How the politics of fertility relate to the subjugation of the natural world

In June 1648, a Puritan midwife named Margaret Jones was executed by hanging from an elm tree in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The reason, as recounted by the governor of the colony at the time, John Winthrop, was that she was a healer. “She practi[ced] physic,” he wrote in his journal, “and her medicines being such things as, by her own confession, were harmless—as anise-seed, liquors, etc.,—yet had extraordinary violent effects.”

Perhaps even more alarming to her accusers, it seems, was Jones’ confidence in her own medical judgment. “She would use to tell such as would not make use of her physic,” Winthrop continues, “that they would never be healed; and accordingly their diseases and hurts continued, with relapse against the ordinary course, and beyond the apprehension of all physicians and surgeons.”

That a woman was put to death because she was practicing what amounts to 17th-century allopathic medicine is shocking when seen through a contemporary lens. For centuries before Jones’ horrific end, though, women dedicated to the healing arts had been targeted by witch hunts throughout Europe. In fact, an edict from the Catholic Church in 1322 unequivocally stated, “If a woman dare to cure without having studied she is a witch and must die.” Since no women were allowed to study medicine at the time, this meant that all female healers, herbalists, and midwives took their lives in their own hands every time they dared alleviate the suffering of their mostly female peasant patients.

The fact that Jones was executed a little more than three miles from what is now Harvard’s Graduate School of Design is not lost on architect and activist Malkit Shoshan. Her exhibition Love in a Mist (and the Politics of Fertility) provides a trenchant exploration of the many ways in which the enduring struggle for control over women’s bodies that had such brutal expression in the witch hunts not only persists but is intertwined with the ongoing subjugation of the natural world. In other words, Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Shoshan took as her starting point the increasing number of threats to Roe v. Wade—including the so-called heartbeat bills that propose banning abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected and the “domestic gag rule” on Title X family planning services that would effectively shut down the only means of birth control and pregnancy counseling to 4 million of the country’s most vulnerable women. For those who wonder what all this has to do with architecture and design, consider this: The domestic gag rule calls for the physical separation of clinics that offer family planning and those that offer abortions, in effect necessitating the building of off-site clinics—a prospect that is simply too expensive for most to consider.

“I figured out early in my studies how you could understand politics and policies through space,” says Shoshan, who has spent much of her professional life studying and mapping aspects of the territorial conflicts between Israel and Palestine. Love in a Mist is grounded in the feminist scholarship of Silvia Federici, whose recent book, Witches, Witch-hunting and Women , draws a direct parallel between the contemporary political war on women and the witch hunts of the past, and architect Lori Brown’s ongoing research into the highly contested space of abortion clinics . Shoshan conceived of an exhibition in which visitors would not only experience up close artifacts and documents from distant and recent histories concerning the control of female fertility but also evidence of the same being done to nature at large. Multisensory artworks provide intense experiences of these themes. Cleverly, the exhibition flows through a series of constructed “greenhouses”—those places, Shoshan says—“where you practice care and reconnect with nature—a space of intimacy and connection and regulation in a soft way.”

Shoshan conceived of an exhibition in which visitors would not only experience up close artifacts and documents from distant and recent histories concerning the control of female fertility but also evidence of the same being done to nature at large.

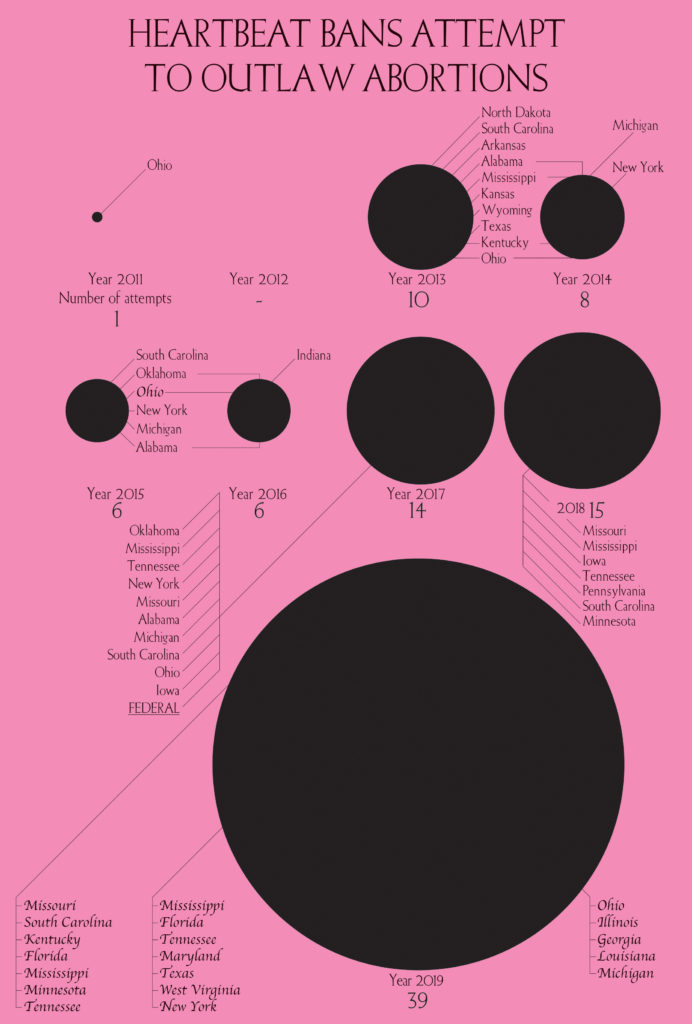

The exhibition takes its lyrical title from the name of a purple flowering bush used in folk tradition to regulate fertility. And perhaps not surprisingly, Shoshan’s first greenhouse is focused on the history of abortion. It includes an example of a recipe for an herbal potion that was thought to have been destroyed by the witch hunts but was rediscovered by medical historian John Riddle; graphics representing the explosion in attempts to outlaw abortion since 2011; and maps and essays by Lori Brown outlining the tremendous distances between clinics in Texas. There is also stunning documentation of the work of Rebecca Gomperts , the Dutch doctor and activist whose organization, Women on Waves , has brought the means of abortion to countries where it is outlawed. A-Portable—a container clinic for traditional abortions designed by Gomperts’ compatriot, artist Joep van Lieshout —is mounted on boats for use in international waters, and abortion pills have been delivered via drones. Gomperts’ work provides a bold and compelling counterpoint to those women who tragically lost their voice in history doing what amounts to the same thing.

By focusing on the acceleration—rather than the inhibition—of growth, the exhibition’s second greenhouse area explores the impact of 20th-century hormones and fertilizers on the female body and the natural world. Despite its much-touted benefit of improving the retention of pregnancies, for example, the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (or DES) proved not only to be ineffective but also harmful to the women who took it, as well as to their children. Although the FDA issued a bulletin to doctors in 1971 that linked prenatal DES prescriptions to a rare form of vaginal cancer, it did not withdraw actual approval of the drug until 2000. Even the US Department of Agriculture banned its use in 1979 as a growth stimulant in livestock. The dichotomy certainly gives the impression that the government cares more about cattle than women.

The blunt force trauma of such statistics are brought to life in Bodies on Steroids—a line-up of supersized blow-up animals, vegetables, and fruits that are sight gag and grotesquerie at the same time. Whether or not the future will bear such Brobdingnagian beasts, the message is clear: Anthropocene alteration of nature inevitably has its consequences, whether visible or invisible. The exhibition’s inclusion of several installations from “soundscape ecologist” Bernie Krause poignantly illustrates this point. By painstakingly recording landscapes around the world for decades—including near his home in Sonoma County, California—Krause has tracked the definitive silencing of what he calls nature’s “biophony,” not only with audible soundscapes but also with the graphic visualizations of sound. Through this compelling methodology, he shows, in Sounds of Extinction, how the purportedly sustainable practice of selective logging has had a devastating impact on local wildlife—even if the landscape looks virtually unchanged to the eye.

The unnatural growth of nature is a theme in Dutch artist Desirée Dolron ’s stunning and eerie Uncertain. Her video installation focuses on a cypress swamp on the Texas/Louisiana border that is threatened by the hostile invasion of Salvinia, an aquatic plant imported from Brazil as aquarium flora that was mistakenly introduced into the Texas ecosystem in 1998. It is the perfect segue to the exhibition’s third greenhouse, which teases out the dire warnings of a landmark United Nations climate report released by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services this past May. The proliferation of invasive species turns out to be one of five major factors imperiling the one million animal and plant species facing possible extinction in upcoming decades due to human activity.

The endgame of unchecked Western economic growth is not progress and equity; it’s overdeveloped land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and displaced species run amok. The bright spot in the report’s otherwise foreboding contents is the establishment of a task force that not only recognizes the wisdom of indigenous and local communities around the world but vows to include them in environmental governance efforts going forward. It’s a smart—if overdue—idea given that land managed by these communities is declining less rapidly than those overseen by industrialized populations.

The future, it turns out, will have to learn more from the past or else risk diminishment or even extinction. While the Margaret Joneses of the world are buried in time, perhaps their message of cultivating nature, self-sufficiency, and effective folk traditions are not. Love in a Mist concludes its compelling quest with a host of future imaginaries that propose alternatives to our current apocalyptic pathway.

The endgame of unchecked Western economic growth is not progress and equity; it’s overdeveloped land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution, and displaced species run amok.

The final greenhouse begins with a neon sign that asks What if Women Ruled the World?—the title of Israeli artist Yael Bartana’s compelling stage performance, which intermingles an all-female cast with legislators, advocates, thinkers, and scientists in a Dr. Strangelove–reminiscent doomsday scenario. With two-and-a-half minutes to go on the doomsday clock, Bartana posits that perhaps only women can break from the patriarchal orthodoxy that has brought us to the brink of global disaster.

Franco-Guyanese-Danish artist Tabita Rezaire ’s 21-minute video installation, Sugar Walls Teardom, continues the provocation with an exploration of the critical wounding of the womb—particularly for women of color. They have been used as guinea pigs to further white gynecological “progress”—evidenced by the “father of modern gynecology” James Marion Sims’ brutal experiments on unanesthetized slaves and Dr. George Gey’s surreptitious capture and cultivation of Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells, now immortalized in the so-called HeLa line. Through her own particular form of “digital healing activism,” Rezaire proposes to decolonize the womb not only through calling attention to the past in her video but through swirling digital collages, empowerment slogans, energy work and, finally, a guided meditation meant for collective—not just individual—transformation.

Just a few steps past Rezaire’s video sits Joep van Lieshout’s larger-than-life sculpture of the female reproductive system, as if reborn from its history of trauma. Pink, fleshy, unapologetic, van Lieshout’s Womb seems to be the return of the repressed writ large and an elucidation of Rezaire’s proposition that “The womb is the original technology”—one with its own power and intelligence that is forever being poured into the world for the sake of the collective rather than amassed for personal gain.

Though Shoshan’s exhibition seems to end on a hopeful note, Desirée Dolron’s final work, Complex Systems, may just have the last word. A mesmerizing recreation of murmurations—the wheeling, gyrating swarming of thousands of starlings—Dolron’s digital depiction addresses the very question of the role of the individual within a collective. It simultaneously confronts the still mysterious wisdom of flock behavior in nature and the overwhelming menace of the political hive mind that has gotten us into our current political predicament. The fluttering of bird wings in Dolron’s affecting audio track seems matched by the incoherent mutterings of some infernal source. In the end, perhaps, it’s the very title of Shoshan’s show that best alludes to such polarity. After all, another name for the purple flowering love-in-a-mist is devil-in-a-bush.

Carbon Park, LA

Augustinas Indrasius (MDes ’19), Peteris Lazovskis (MArch I ’20), and Thomas Schaperkotter (MArch I ’20)

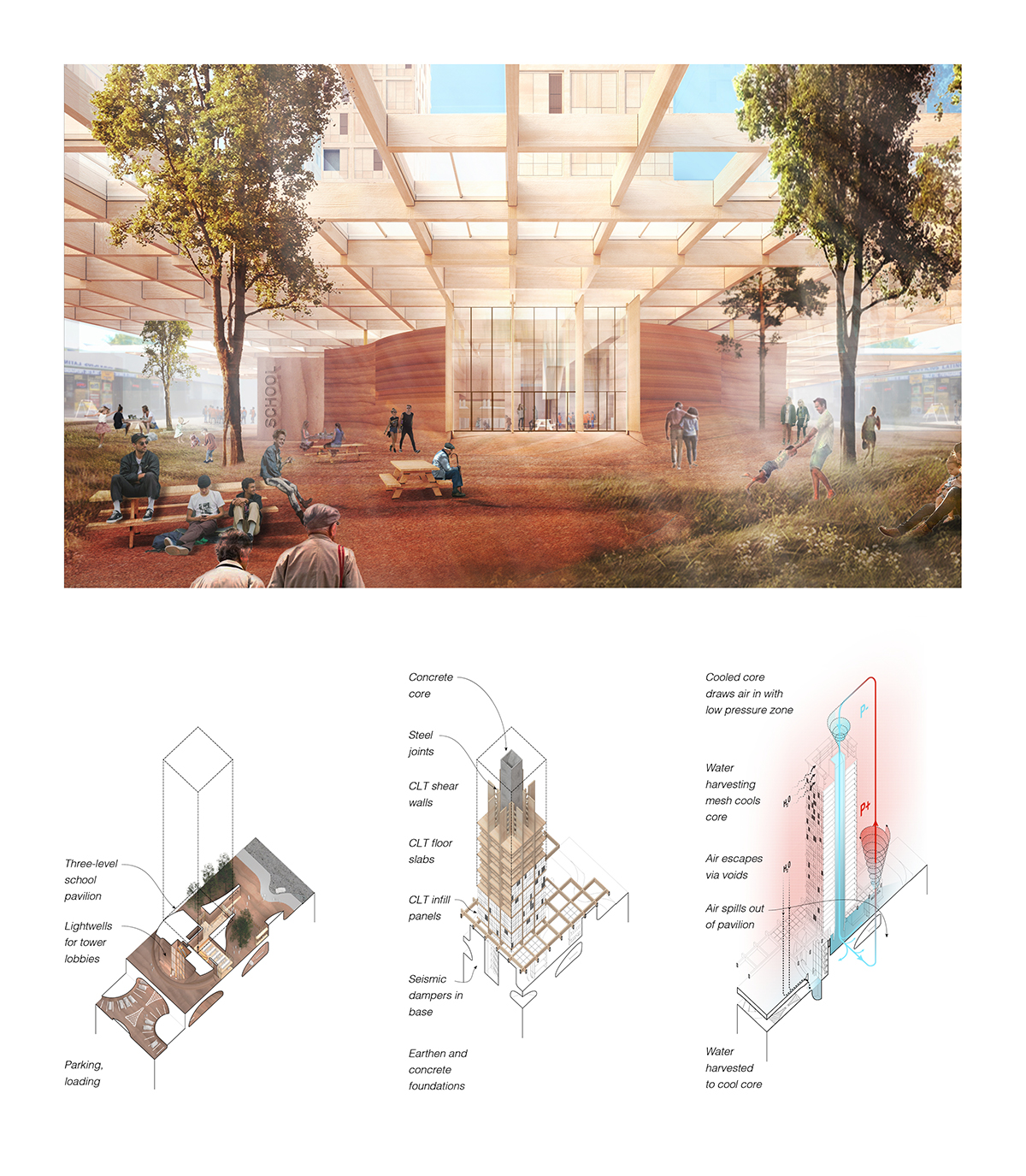

Carbon Park, LA reimagines how real estate investment may fuel social benefit and ecological sustainability by connecting private investment with public space to seek balance for investors, the downtown Los Angeles community, and California’s growing carbon economy.

The Hidden Room Elevation

Diandra Rendradjaja (MArch I ’22)

The elevation of this architecture conceals not only the dynamic sectional quality of the interior but also the perceptual discrepancies created through forced perspective manipulation that produces a defamiliarization through scale. Throughout the project, perceptual scale distortion happens mostly in interior framed views while the facade remains static and mute. This representational experimentation investigates the elevation drawing as an instrument to reverse this reading of perceptual scale distortion from an interior depth in the longitudinal orientation to an elevational depth in the transversal orientation.

Taking the elevation of the “normal” room as the stable and ideal scale and projecting it to the other altered rooms produces a new set of elevation that begins to reveal depth as some room appears larger or smaller than the others. This is then re-interpreted as a new form of architecture where each room is an independent volume that intersects three-dimensionally with one another. In contrast with the original architecture, the new architecture expands to a thicker form towards the transversal direction that disrupts the single longitudinal reading of the existing.

Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee profiled in the Los Angeles Times: “Buildings that make you say, ‘Huh?,’ then ‘Wow!'”

Harvard Graduate School of Design professors (and alumni) Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee, and their Los Angeles-based practice Johnston Marklee, have been profiled by the Los Angeles Times in a feature entitled “The L.A. architects who design buildings that make you say, ‘Huh?,’ then ‘Wow!'” In surveying a range of Johnston and Lee’s projects–including the recently opened Menil Drawing Institute in Houston and UCLA’s Margo Leavin Graduate Art Studios in Culver City–the Los Angeles Times notes the “grace” of the duo’s work, as well as the inability to assign Johnston and Lee to one, single category of architect.

“Previous generations had a signature style, and it’s easier to label,” Lee observes in the feature. “Our generation wants to escape that.”

Johnston and Lee joined the GSD faculty in 2018 as Professors in Practice of Architecture. Additionally, Lee was named Chair of the GSD’s Department of Architecture that same year. Johnston and Lee’s Los Angeles Times profile offers a look, visually and conceptually, at a series of their firm’s works, presenting thoughts and reflections from various clients for whom the duo have designed.

“The path of their career is that they have the capacity to do different kinds of projects, but with the certainty that you will get Johnston Marklee quality,” says Brett Steele, dean of UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture. “It’s a tricky thing for architects. It takes a degree of confidence.”

“All of this is the work of an architectural studio that is less preoccupied with planting Instagrammable icons than in creating structures,” writes the profile’s author Carolina Miranda, “that react to local context in deliberate ways.”

“Our generation, globally, a little older or younger, we are more interested in the fabric of cities,” Johnston tells Miranda. “Not just the monuments and icons. It’s about understanding how we relate to the things around us. Not just ourselves.”

“A good building is like a good friend,” adds Lee. “If you want to be left alone, they will leave you alone. They will let you be quiet. But if you engage, they can tell you a lot.”

Johnston Marklee has been recognized nationally and internationally with over 30 major awards. A book on the work of the firm, entitled HOUSE IS A HOUSE IS A HOUSE IS A HOUSE IS A HOUSE, was published by Birkhauser in 2016. This followed a monograph on the firm’s work, published in 2014 by 2G.

Projects undertaken by Johnston Marklee are diverse in scale and type, spanning seven countries throughout North and South America, Europe, and Asia. The firm’s work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Menil Collection, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Architecture Museum of TU Munich. Johnston and Lee were also the Artistic Directors for the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial.

The Affordability Crisis: What are the greatest challenges to affordable housing today?

At Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, affordable housing is an urgent concern in the pursuit of healthy, equitable cities. In this video—the first in a series of brief looks at the ways in which topical issues are explored at the GSD—Rahul Mehrotra, Daniel D’Oca, and Farshid Moussavi discuss strategies for rethinking the housing needs of the 21st century.

Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu

Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu

In this episode of Talking Practice, host Grace La interviews Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu, partners and co-founders of Neri&Hu Design and Research Office , and the John C. Portman Design Critics in architecture at the GSD. Lyndon and Rossana reflect on the beginnings of their personal and professional partnership, and the deep significance of founding their practice in Shanghai. Discussing the risks and rewards involved in starting a practice in a foreign city, Lyndon and Rossana provide insights into their working dynamic and the ways in which they leverage China as a laboratory for product design and architectural production. Presenting an inside glimpse into the logistics of their office, they stress the importance of moving beyond an “idealized practice” by experimenting with different business models. As practitioners working across multiple scales, cities, and industries, they articulate their attempts to balance tactility and diagrammatic thinking while leveraging the unique cultural contexts of their practice.

Lyndon and Rossana also describe the ways in which their practice serves as a catalyst for the revitalization of China’s depopulated rural villages, and how their work with adaptive reuse projects lies at the core of their relationship with developers. For more on Lyndon and Rossana’s work in adaptive reuse, check out their fall 2019 option studio.

Lyndon Neri and Rossana Hu are partners and co-founders of the Shanghai-based Neri&Hu Design and Research Office , and the John C. Portman Design Critics in architecture at the GSD. Lyndon and Rossana are known internationally for their work in adaptive reuse projects, including the Waterhouse at South Bund , the Aranya Art Center , and the Tsingpu Yangzhou Retreat . Working across disciplines in industrial and product design, they are also the creative directors of the furniture brand Stellar Works and founders of Design Republic , a retail brand and online platform that showcases the work of internationally renowned designers. Lyndon and Rossana are the recipients of the Elle Décor International Design Awards, and have been inducted in the U.S. Interior Design Hall of Fame. They are currently teaching a studio at the GSD entitled “Reflective Nostalgia: Alternative Futures for Shanghai’s Shikumen Heritage.“

About the Show

Developed by Harvard Graduate School of Design, Talking Practice is the first podcast series to feature in-depth interviews with leading designers on the ways in which architects, landscape architects, designers, and planners articulate design imagination through practice. Hosted by Grace La, Professor of Architecture and Chair of Practice Platform, these dynamic conversations provide a rare glimpse into the work, experiences, and attitudes of design practitioners from around the world. Comprehensive, thought-provoking, and timely, Talking Practice tells the story of what designers do, why, and how they do it—exploring the key issues at stake in practice today.

About the Host

Grace La is Professor of Architecture, Chair of the Practice Platform, and former Director of the Master of Architecture Programs at Harvard University Graduate School of Design. She is also Principal of LA DALLMAN Architects, internationally recognized for the integration of architecture, engineering and landscape. Cofounded with James Dallman, LA DALLMAN is engaged in catalytic projects of diverse scale and type. The practice is noted for works that expand the architect’s agency in the civic recalibration of infrastructure, public space and challenging sites.

Show Credits

Talking Practice is produced by Ronee Saroff and edited by Maggie Janik. Our Research Assistant is Jihyun Ro. The show is recorded at Harvard University’s Media Production Center by Multimedia Engineer Jeffrey Valade.

Palladio and Raphael: An Innovative Learning Experience

Two leading scholars of the architecture of Andrea Palladio, Guido Beltramini and Howard Burns of the Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio, Vicenza, will offer workshops exploring Raphael (1483-1520) and Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), two of the most influential architects of the Renaissance, and the relation between them. Though they had different backgrounds – Palladio trained as a stone carver, whereas Raphael was the son of the court painter in Urbino – they are similar in their view of history, their concern with architectural drawing and representation and commitment to the study and imitation of ancient Roman architecture. Raphael must have been a major source of inspiration for Palladio, who in Rome made a survey plan of his masterpiece, the villa Madama. He also adopted elements of Raphael’s architectural language. He would have noted Raphael’s skill in creating personalized palaces for high functionaries in Pope Leo X’s inner circle.

The fall session Faking Palladio will introduce students to Palladio’s world, requiring them to produce a fake Palladio drawing. This requires in-depth knowledge of both the material character of the work to be imitated and also the cultural background of the architect imitated. Students will not be invited to produce an exact copy of an existing drawing but to invent a drawing that has never existed. This sort of exercise is made possible because Palladio developed an architecture that he conceived as a language, based on standard elements (such as rooms, stairs, doors, and columns) with proportions governing the relations between the various components. Palladio's treatise, The Four Books on Architecture (Venice, 1570), is essentially a manual with instructions referring to his architecture. Among Palladio’s drawings we find drawings for unbuilt buildings: many of them are plans without the corresponding elevations. To make a fake Palladio drawing, a good starting point is a Palladio original plan from which to imagine a possible development. The students will be asked first to design the elevation, or part of it, then to make a fake, focusing on the materiality of the drawing as an object (the paper, ink, stylus drawn lines, etc.) and on Palladio’s drawing conventions, which are close to those used today.

This spring session Anticipating Palladio will be dedicated to Raphael, always considered as one of the greatest painters. However, he was also a brilliant and innovative (and still little-known) architect, whose approach anticipates Palladio’s. The spring session will consist of lectures, workshops, and seminars on the buildings to be visited during the trip. Topics to be covered include Raphael’s architectural formation (in Urbino, Perugia, Florence and Rome), his writings and ideas, drawings, painted architecture, buildings and design methods, as well as his social world of friends, collaborators, patrons, and rivals, including Michelangelo. Students will explore the complex relation in Raphael between study of ancient Roman architecture and the design of modern buildings, and his revival of Roman constructional techniques and modes of interior decoration. Unbuilt, unfinished or destroyed works by him will be reconstructed in drawings and models. Raphael will also be approached as a “proto- film director”, creator of marvelous single-shot still “movies.” The seminar will offer an exceptional educational and architectural experience and will have a specific goal and outcome: generating ideas and prototypes for virtual and physical models for the exhibition IN THE MIND OF RAPHAEL, Raphael as Architect and inventor of architecture, to be held at the Palladio Centre in Vicenza (Oct. 2020 – Jan. 2021).

Factory of the Sensible and the Political* (Equipping Experience)

Architects have long experimented with altering perceptions of space and structures in order to reconfigure experience.

At stake in this course are pivotal historical and theoretical transformations in our understanding of perception and experience that are relevant to our contemporary architectural interest in these concepts.

Behind these transformations lie different instantiations of humanism, proximate or remote technologies (equipment), explosive or suppressed uses of ornamentation, lineages of the sublime, conceptions of the visual, reformations of nature and body, object ontologies, the invention of the life sciences (sensory systems), cybernetics and non-linear dynamical systems theory. Socio-political agency, in these contexts, are often new tables of operation embedded in aesthetic provocations.

Walter Benjamin wrote in 1935 that modes of perception change when upheavals happen in the history of human life. Fredric Jameson, on the other hand, argued in 1991 that the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, designed and built by John Portman, was a “mutation in built space” that is “unaccompanied as yet by any equivalent mutation in the subject.”

Students will read seminal texts and we will collectively discuss evocative architectural projects. A presentation and two short papers will be required. No prerequisites.

Domestic Orbits: Frida Escobedo on architecture’s tendency to conceal spaces of domestic labor

Selective concealment is a typical, though often unacknowledged, function of architecture. Architectural detailing, for example, shrouds the processes and defects of construction and hides the complex mechanics of buildings. Moldings mask the ragged intersection of walls with floors and ceilings. Wallboards cover structure, plumbing, electrical wires, and insulation. In covering panel joints, tape, plaster, and paint conceal dimensioned boards behind an illusion of material uniformity. Dropped ceilings shield pipes, ductwork, and rough concrete. All of this seems practical and acceptable—almost essential—in buildings. In fact, the 20th-century architectural critic Reyner Banham asserted that these kinds of efforts “clearly satisfied one of the leading aesthetic ambitions of modern architecture….” Hung ceilings and hidden ductwork—“concealed power,” he called it—offered visual purity despite the clutter of modern service systems.

But Banham also pointed out the intellectual and ethical incongruity of this achievement in modern architecture: “It flouted one of its most basic moral imperatives, that of the honest expression of functions.” By the time Banham wrote these words in the late 1960s, “honesty” had been well established as one of architecture’s fundamental obligations. This dated back at least to John Ruskin, who wrote in “The Lamp of Truth” in 1849, “We may not be able to command good, or beautiful, or inventive, architecture; but we can command an honest architecture.” “What is there but scorn,” he asked, “for the meanness of deception?”

Ruskin’s Victorian moralizing may seem overwrought, but his attention to the corrosive effects of small deceits still seems relevant. Even if we become inured to the regular untruths in architectural detailing, we should still scorn architecture’s larger efforts at deception. We might accept the mild untruth of moldings, for example, while we still abhor the capacity of well-composed architecture to mask duplicity or hide suffering. The challenge for architects and students of architecture is to remain attuned, as Ruskin was, to the ethical capacities of architecture and to ensure that aesthetic ambitions do not obscure decency or foster inequity. We must acknowledge that design, even at the scale of the smallest detail, is not morally or politically neutral.

How can architectural interventions help recognize, reduce, and redistribute the problems faced by domestic workers?

Frida Escobedowho, together with Xavier Nueno, seeks to highlight ways in which iconic Mexican architects had erased the spaces of domestic labor.

Frida Escobedo, who is teaching an architecture studio at the Graduate School of Design this semester that is supported by Knoll, Inc. , explains the studio’s origin as a moment of discerning architectural deceit. As a participant in the 2007 Ordos 100 project to design a house in Inner Mongolia (according to ArchDaily: “one hundred 1,000-sqm villas designed by 100 hip architects in 100 days”), she noticed an oddity in the architectural program: The single-family house was to include two kitchens. But to Escobedo, “Two kitchens equals two households in one house, and it just stuck in my head.” It implied a household of hidden servants who would prepare the food in one kitchen so that it could be presented in the other kitchen—a space of entertainment for the homeowners. The project brief thereby suggested that the architects should render one household invisible, even as the house itself would become a showpiece for the architecture firm and for the wealthy family who purchased it.

Escobedo began to focus on the systematic, global tendency of architecture to conceal spaces of domestic labor—and the people (mostly women) who work in them—a process she calls “invisibilization.” Earlier this year, Escobedo highlighted this in Domestic Orbits , a detailed study of five modern domestic buildings in Mexico. The book offers “a counter-history of Modern architecture that questions the duality among the visible/invisible, those who count and those who do not.” Xavier Nueno, her collaborator on both the project and the GSD studio that bears the same title, explains that the study’s aim is to highlight how “iconic Mexican architects” had “erased the spaces of domestic labor.” Using techniques of mapping, Escobedo and Nueno show that the forces that bind together the owners of the houses and their domestic laborers also serve to keep them apart in spatially distinct domains, just as a dynamic tension causes a celestial body and its satellites always to circle each other.

In some cases, as at the Casa Estudio Luis Barragán, space for domestic labor becomes embedded in the house, nesting one hidden household within another. In other cases, housing for domestic workers spins off into other domains within the city—as in the wealthy Mexico City neighborhood of Polanco, where obscure ancillary buildings contain parking and cramped servant housing. The book also points out that architectural representation of these projects, particularly published drawings, put “a veil between owners and workers,” because they almost invariably fail to show the servants’ quarters. Domestic Orbits highlights how architecture’s selective concealment of domestic space makes it complicit with great social inequities associated with gender, class, and race in Mexico.

The Domestic Orbits studio begins with Escobedo and Nueno’s historical account and extends into the realm of design. The studio brief explains that a recent political change in Mexico is likely to significantly alter the balance of forces involved in domestic labor. “In December 2018,” it says, “the Mexican Supreme Court recognized the right of domestic workers to be affiliated to social security putting an end to a long history of discrimination and invisibility.” Certainly, this will offer momentous change for a great number of people, and, because architecture was complicit in the discrimination that led to this new law, it too will need to change.

The brief asks how the consequent entry of 2.4 million workers into the formal economy will reshape not only the social dynamic in Mexico, but also the domestic and urban spaces that bring people together. Escobedo explains that because these workers provide much of the “reproductive labor” in the Mexico—cooking, cleaning, maintenance, care of the elderly, and so on—they will become increasingly visible, moving from traditionally hidden spaces into the public realm. The studio therefore asks students: “How can architectural interventions help recognize, reduce, and redistribute the problems faced by domestic workers?”

To begin answering this question, the 12 students in the studio began by mapping the spaces of domestic work in Mexico City. This has not yet been done systematically, so “it has been really challenging,” Escobedo says. But the students have been resourceful and have made some important discoveries—about the social isolation of domestic workers within dense urban blocks, the safety of these “hidden” people on public transportation, and the “invisible thresholds” that limit their movement in the city. The students presented this work in the form of analytical maps that will orient their thinking and help create narratives about the changing situations of domestic workers in the city.

After a month of research, the students embarked on a week-long trip to Mexico City. Their first stop was the Bordo Xochiaca, an immense landfill decommissioned and capped in 2006 as part of an effort to improve a vast impoverished area of the city. Escobedo explains that the tour began there because “it is important for students to understand the periphery—the ‘informal’ but highly structured space” in the city’s poorer districts. “Mexico City is several cities in one,” she says. One aim of the group’s visit is to seek out the thresholds between sectors of the city, the “dark zones and gaps” where the problems of domestic workers are acute and where architectural interventions might be most effective. The itinerary also included public markets, modernist housing projects by Mario Pani and others, the Casa Barragán, and offices of architects who are also working on the issues presented by the studio.

Back in Cambridge, the students are developing intervention strategies that address and foreground the conditions of domestic laborers and “help realize the provisions made by the new law.” These might include building proposals, but also, Escobedo emphasizes, “representations of spaces, territorial organizations, utopian landscapes, policy proposals, or other forms of spatial practice.” While it addresses the specific conditions in Mexico City, the studio encourages broader speculation about how architecture operates in legal, social, and political spheres, and seeks a deeper moral imperative for architecture. Its aim, in particular, is to systematically reveal “structures of inequality” that were formerly concealed by architecture.

While the Domestic Orbits studio follows Escobedo’s long-term interests and recent research, she notes that it also reinforces and informs her evolving architectural practice. Since its inception, her firm has been “based on the idea that architecture and design represent a crucial means of posing questions and contesting social, economic and political phenomena.” As they begin to take on multifamily and social housing projects in Mexico, Escobedo and her collaborators naturally gravitate toward the difficult questions, seeking out ways to resolve hidden tensions of domestic life and investigating the roles domestic architecture plays in the social dynamic. Frida Escobedo’s work on domestic orbits—her research, teaching, and practice—seeks to refocus the moral imperative of modern architecture by underlining social conflict and confronting hidden inequities.