Plot Zero: Sensing the Landscape to Map the Dynamic Atmospheric Environment of the Urban Fabric

Introduction

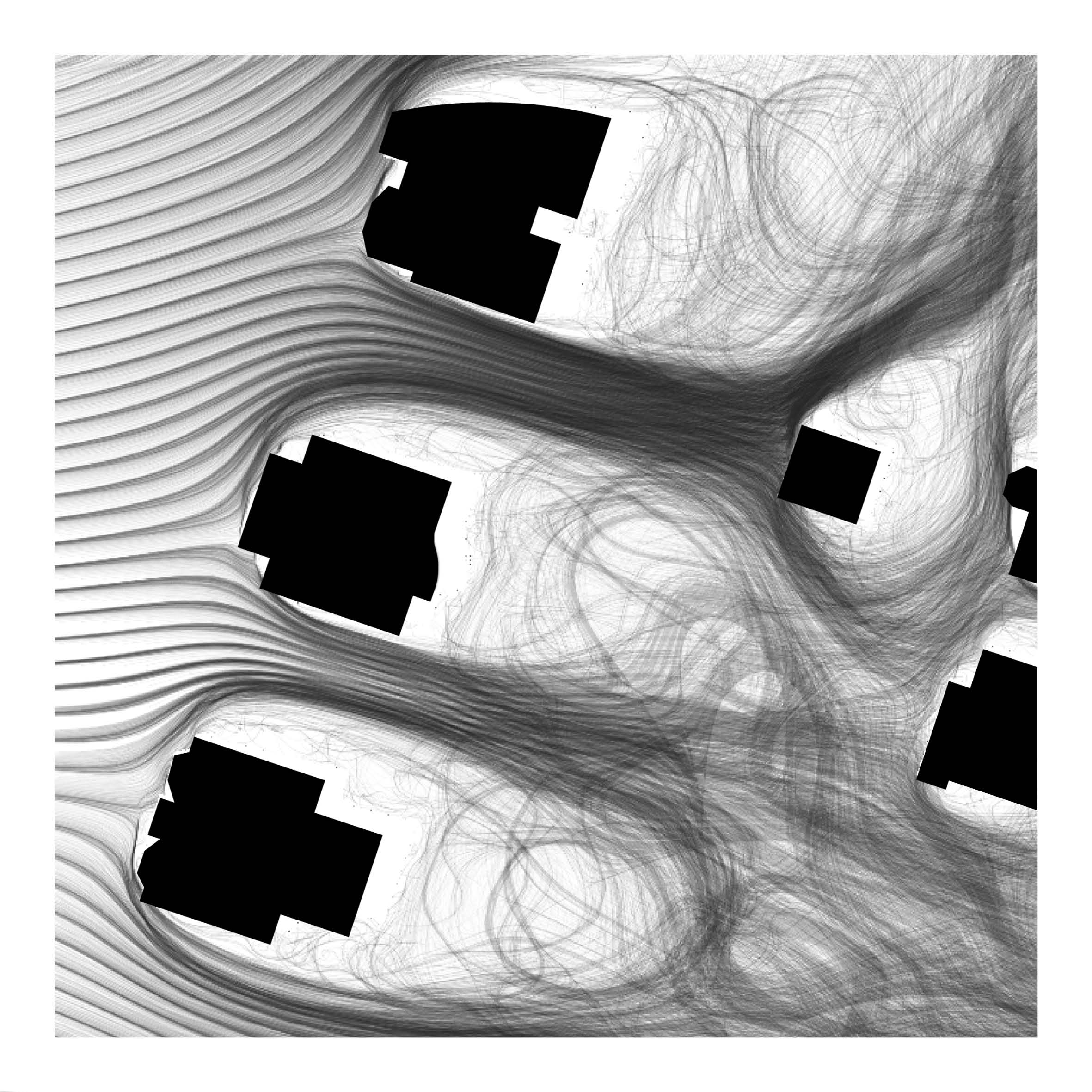

Working at the nexus of the social, ecological, and technological in the built environment the project explores remote sensor technologies capable of continuous in-operation monitoring to measure atmospheric conditions at a hyper-local scale in the landscape. This approach seeks to make visible and reconstitute the urban landscape as a complex temporal and material manifold of differential space shifting across multiple scales in a constant state of flux. The research explores how a sensor network may be deployed to measure and describe airborne territories that might augment and challenge traditional concepts of site in which air is a matter of entanglement and interconnection.

Description

A great deal has been invested into significant advances in energy conservation and sustainability in building design, construction, and management. This also includes the time of their subsequent occupation and operation through the continual monitoring of building performance involving sensors and computational simulation to optimize energy efficiency and comfort. Sensor technology can change the way we understand and potentially radically transform the urban environments that are our cities. The technology augments the human perceptual field and enables a “dynamic, flexible and interactive mapping of reality, fueled by the staggering amount of data we produce” (RATI 2019) and ways of visualizing the data in real-time to inform better design and management of cities.

The research considers how this technology might enable ways to analyze and visualize the multiscalar, dynamic, and elusory matter of air and utilize it as a measure in, and of, the constructed landscape environment. How might we explore and speculate on our capacity to inform its continual becoming and its reciprocal effect as a part of an ecology upon which humans and more-than-humans might survive and prosper? How might this approach create different forms of valuing, assessing, and designing the urban landscape?

The physical composition of the urban fabric acts to absorb, produce, and trap heat, resulting in higher sustained temperatures 1-3 degrees (Celsius) warmer than neighboring rural areas. Heat generated in the city, including waste heat, is trapped along with airborne pollutants generated by vehicles, transport infrastructure, commercial enterprises, and industry. Subsequently, this condition adversely affects water and air quality and the health and well-being of its citizens. Energy demands simultaneously rise due to the prolonged and increased use of mechanical ventilation and air conditioning in response to the hotter temperatures that strain energy resources and further contribute to the production of global emissions.

The premise for the study is House Zero, a model house, facility, and laboratory. The building is a pre-1940’s typical suburban Cambridge “triple-decker” house retrofitted into an ultra-efficient, healthy, positive energy structure. The building contains “nearly five miles of wiring that capture 17 million data points per day. Some sensors are critical to the operation of the building: for example, controlling the system of windows and shades in response to inputs about temperature, rain, wind direction, and indoor CO2 levels and airflows.” (MALKAWI 2019). The house “promotes holistic change within the built environment, namely through the creation and continued improvement of sustainable, high-performance buildings and cities.” (MALKAWI 2019)

Method

To support and augment the aspirations of House Zero the research seeks to expand the active sensor network outside the building envelope to the extent of the home’s plot boundary. The intention was to gather data specific to dynamic environmental parameters (e.g. solar and infrared radiation, air temperature, humidity, wind speed, carbon dioxide levels and significant air pollutants) that dynamically shape the network of outdoor urban spaces that envelop the building. This sought to understand the impact of the composition of outdoor spaces on the energy efficiency of the House Zero building operation. The enquiry asked how the landscape might support, or hinder, the efficient heating and cooling of the building, and how the building control system could be further augmented to act more carefully and efficiently with the external air qualities. This might include, for example, the utilization of optimal external conditions that may vary around the building at different times, and the identification of hazards that might alert and prevent venting the house from windows exposed to poor air quality that may arise, such as high levels of vehicle pollutants at peak traffic times on the street front.

The work also intended to make it possible to analyze and visualize the complexity of the atmospheric landscape system and identify its propensities in the form of its key operational characteristics. With this understanding, the research aspired to understand the atmospheric agency of the landscape to inform the design of spaces that contribute to the sustainability of the city and improve the health and well-being of its citizens. Given that the air in any one space and moment is a product of upstream conditions that shift and evolve through the outdoor urban landscape network in conjunction with the locally produced effects, and one that simultaneously informs downstream circumstances, the agency of designing an ‘air-scape’ is simultaneously local, territorial, and global.

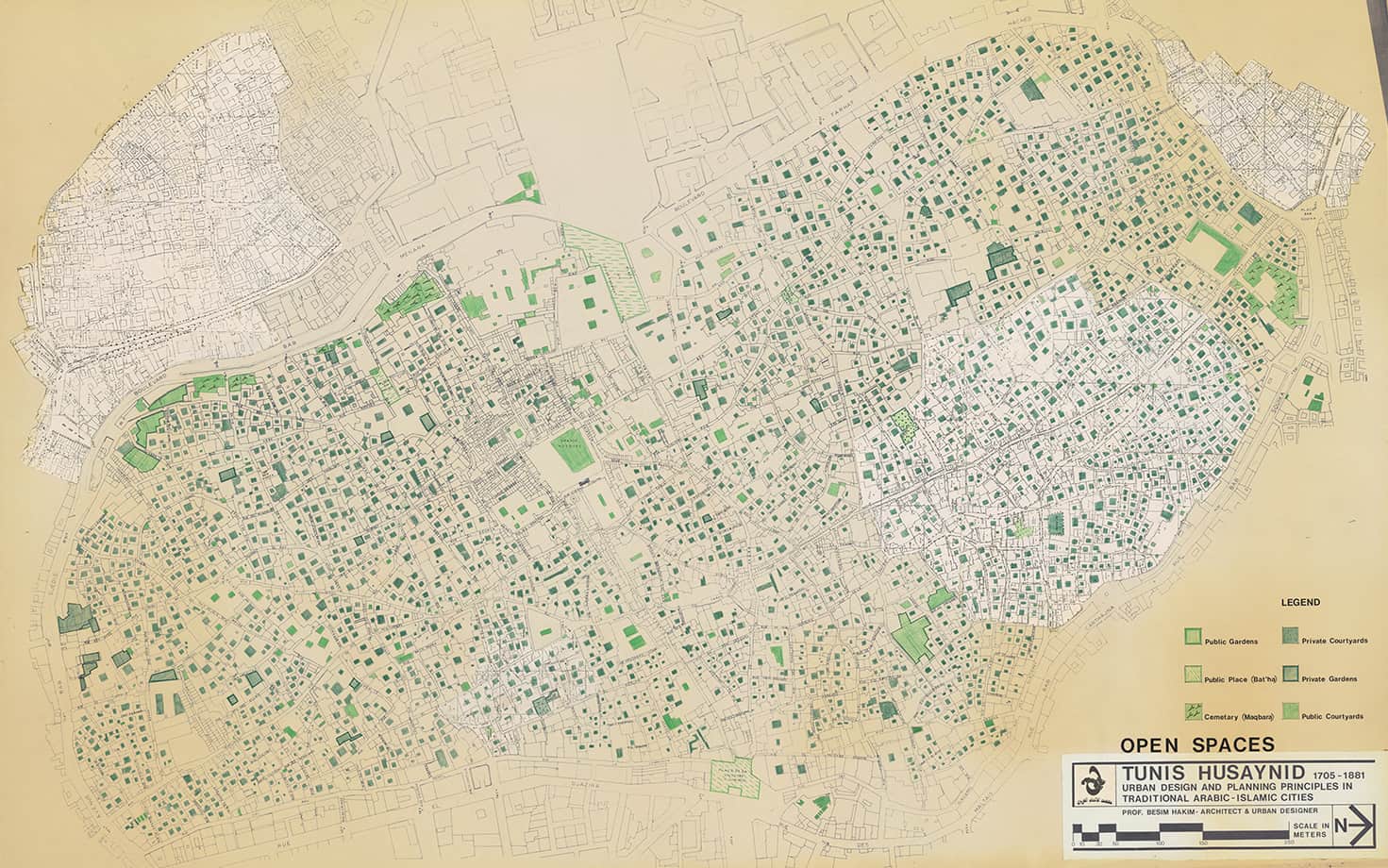

Atlas for the Medina of Tunis: Landscape Architecture as a Catalyst for Urban Regeneration

This project reimagines public spaces in the Medina of Tunis, Tunisia. Taking a long-term view over a five to 50–year timespan, we ask how three interrelated areas of focus—housing, health, and changing climates—intersect with the urban landscape. The project especially considers the nocturnal uses of public spaces as a response to the rising temperatures associated with changing climates. Integrated within the Critical Landscapes Design Lab, we take a landscape architectural approach to the design of urban spaces. Informed by landscape fieldwork, this approach is deeply grounded in Tunis’s environmental, economic, human, and political ecologies. Through this grounded research, we engage with the Medina and its residents to better understand everyday life and spatial patterns that do not appear in official statistics, documents, or records. Knowledge gained from this landscape fieldwork informs design proposals for the reactivation of spaces inspired by the Medina’s current and future material needs.

Materia Inc., Sponsor

Cutting the Tall Grass

Sharon Cornelissen (Postdoctoral Fellow)

Sharon Cornelissen lived and became a homeowner as an ethnographic researcher in Brightmoor, Detroit for three years (2015-2018)—one of the United States’ most depopulated, poor, Black neighborhoods. Since 1970 Brightmoor had lost over half of its residents, while it turned from all-white to 83% Black. Wildflowers flourished here amidst hundreds of emptied homes. Residents saw wild deer as often as they heard gunshots. And in 2006, a surprising new phenomenon began: white middle-class newcomers started to move in, who called themselves “urban farmers” and planted gardens and farms on vacated lots.

Drawing on over 1500 pages of ethnographic fieldnotes and 70 in-depth interviews, Sharon is writing the book Cutting the Tall Grass, in which she sets out to answer two core questions: One, how did extreme decline and depopulation affect the lives of Black and white longtimers? And two, why did middle-class white newcomers move to this devastated place? To answer these questions, she will show how decades of neighborhood decline shaped racialized losses and opportunities, hardship and privilege, and trauma and coping, as devastated Brightmoor faced early gentrification.

Her book revolves around four key chapters. First, she will explain how and why so many longtime Detroiters lost their homes a decade after the subprime mortgage crisis decimated Black communities across the United States. As many Brightmoor homes had become worth less than second-hand cars, and with little to no credit available, many residents became forced to treat their most prized possession as a disposable good: something they were using up. Many longtimers lost their homes to tax foreclosures, often after years of hardship, lost jobs, burnt-out furnaces, leaking roofs, and grief and worries.

Second and by contrast, she will show how white newcomers turned this housing distress into exclusive opportunities. She describes the moral code newcomers used to navigate buying in a market haunted by loss and shows how newcomers turned lost homes into prized Detroit urban farmhouses. She argues that their relative privilege was instrumental to help them profit from one of the United States’ most depressed property markets. Longtimers’ tragedies became white newcomers’ opportunities.

Another chapter of the book examines how longtimers and white newcomers differently related to the return of greenery in depopulated Brightmoor. Some vacated blocks more resembled rolling fields than anything else. Most longtime residents hoped that Brightmoor would regain urban density. They decried wildflowers and tall grasses as weeds. Many vigorously mowed vacant lots. White newcomers, by contrast, supported wildflower fields and housing demolition without rebuilding. They viewed vacated blocks as country-like and kept chickens, goats, and honeybees. What Sharon calls “traumas of decline” shaped whether residents foregrounded depopulated nature as blight or bucolic, as urban absences left in the wake of depopulation and disinvestments, or as new rural presences, signaling Brightmoor’s incipient ruralization. Acting on and with nature, residents worked through ideals of decency and respectability, through feelings of control and anxieties about violence, and through conflicting dreams of urbanism or post-urbanism.

Finally, she discusses how white newcomers’ and longtimers’ different relationships to the neighborhood’s past shaped their public lives. Traumas of neighborhood decline and historical violence lingered for longtimers on street corners, in fields of tall grass, and in unsuspecting moments. By contrast, for white newcomers, historical violence was only a fact of oral history, rather than lived biography. Their strategies for navigating public life came from positions of white privilege, and their aspirations for Brightmoor were often based on their experiences growing up in white, middle-class neighborhoods. As a result, white newcomers often acted in ways that other residents considered unsafe, such as by organizing a weekly farmers’ market across from a notorious open-air drug market.

Overall, this project makes significant contributions towards understanding the relationships between urban decline, gentrification, and racial inequality. It also calls for scholars to incorporate an understanding of traumas of decline into their analyses of the detrimental impacts of neighborhood disadvantage. The book offers a thorough analysis of such trauma, its relationship to racialized dispossession, to coping, and dreams of redemptive urbanism. Conversely, it unpacks the distinct orientations, privileges, and historical conditions of white gentrifiers, by closely examining this unusual case of early gentrification.

Human-Building Interaction

Our research has highlighted the challenges of understanding, simulating, and designing for the complex interactions between buildings and occupants. This inspired us to investigate how occupant behavior impacts building-energy performance and, conversely, how energy-related building-design decisions impact occupant health. In short, our focus is on human-building interaction.

This topic area includes multiple current research projects including:

- New benchmarking methods for buildings based on energy use, comfort, and health

- Architectural design considerations for healthy sleep environments in low-energy buildings

- A framework for considering energy performance and mold risks

- Importance of cultural understanding in building energy analysis and simulation

Team Members

Holly Samuelson, Jose “Memo” Cedeno Laurent (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health), Yujiao Chen (DDes), Esteban Estrella (MDes), Jungmin (Ellie) Han (DDes), Pamela Cabrera (MDes), Kenner Carmody (MDes), Christine Voehringer (MDes), Wenting Li (MDes), Christine Tiffin (MDes), Shreejay Tulhadar (MDes)

Affiliated Publications

“Optimal Control of HVAC and Window Systems for Natural Ventilation Through Reinforcement Learning,” Chen, Y., Norford, L., Samuelson, H., Malkawi, A., Energy and Buildings, March 2018.

“The Impact of Window Opening and Other Occupant Behavior on Simulated Energy Performance in Residence Halls ,” Cedeno Laurent, J. G., Samuelson, H.W., Chen, Y., Building Simulation, December 2017

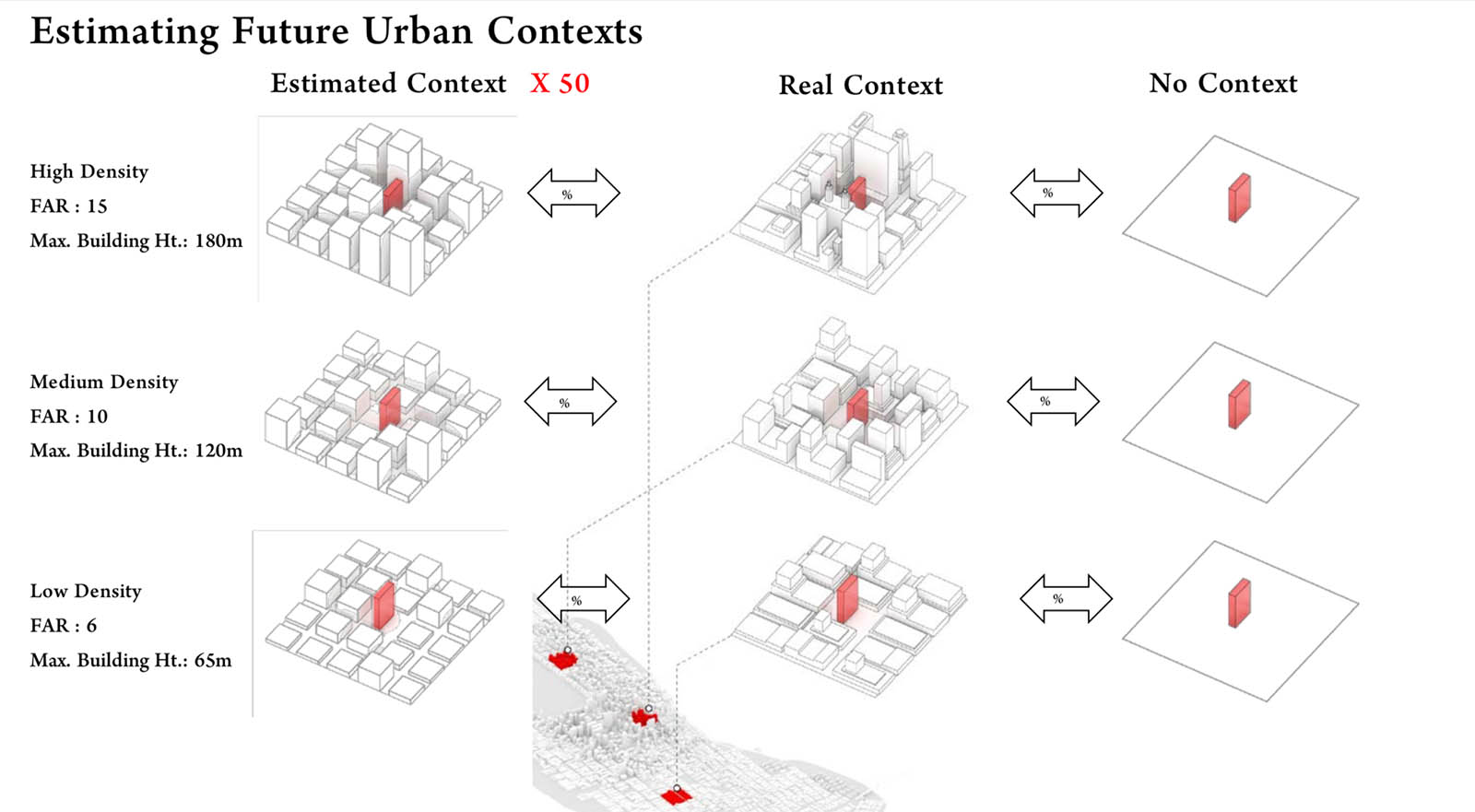

Parametric Energy Simulation in Early Design

This project proposed a framework for the development of early-design guidance to inform architects and policy-makers using parametric whole-building energy simulation. It included a case study of a prototype multifamily residential building, using an exhaustive search method and a total of 90,000+ simulations. The authors performed a simple sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential of the tested design parameters on energy use intensity, which included WWR, Glass Type, Building Rotation, Building Shape, and Wall Insulation, in that order. They identified synergies and trade-offs when designing for different energy objectives, including (a) decreasing Energy Use Intensity, (b) reducing peak-loads, and (c) increasing passive survivability i.e., maintaining the safest interior temperatures in an extended power outage.

This project also investigated the effect of urban context as a source of sun shading and found it to have a substantial impact on the design optimization. Ignoring urban context in energy simulation, a common practice, would mislead designers in some cases and result in sub-optimal design decisions. Since in generalized guidelines the future building site is unknown, the researchers proposed and tested a method for generating urban contexts based on the floor area ratio and maximum building heights of an urban district.

Team Members

Holly Samuelson (Faculty), Sebastian Claussnitzer, Apoorv Goyal (MDes), Yujiao Chen (DDes), Alejandra Romo-Castillo (MDes)

Affiliated Publications

“Parametric Energy Simulation in Early Design: High-Rise Residential Buildings in Urban Contexts ,” Samuelson, H.W., Claussnitzer, S., Goyal, A. Chen, Y., Romo-Castillo, A., Building and Environment, May 20o1

“Parametric Energy Simulation of High-Rise Multi-Family Housing,” Samuelson, H.W., Goyal, A., Romo-Castillo, A., Claussnitzer, S., Chen, Y., Bakshi, A., Proceedings of Simulation for Architecture and Urban Design (SimAUD), Washington, DC, April 2015

Atlas for a City-Region: Imagining the Post-Brexit Landscapes of the Irish Northwest

Centered on the northwest of Ireland, this eighteen-month long research project investigates how a cross-border city-region can be shaped in light of the economic, political and social realities of Brexit. Integrated within the teaching of the department of landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and engaging faculty from across the university, the project asks how landscape can be an agent in the shaping of the cross-border city-region. Located between the counties of Derry, Donegal and Tyrone the cross-border city-region has a population of approximately 350,000, and growing. Through research seminar and option studio, the multi-scalar project will address the design of smaller urban spaces right up to the design of the region itself. The project will demonstrate how the post-conflict Northern Irish landscapes can adapt to post-Brexit conditions, and how landscape architecture can be instrumental in shaping not just the physical landscape but the new political landscape too.

Derry and Strabane District Council, Northern Ireland, Sponsor

Donegal County Council, Ireland, Co-sponsor

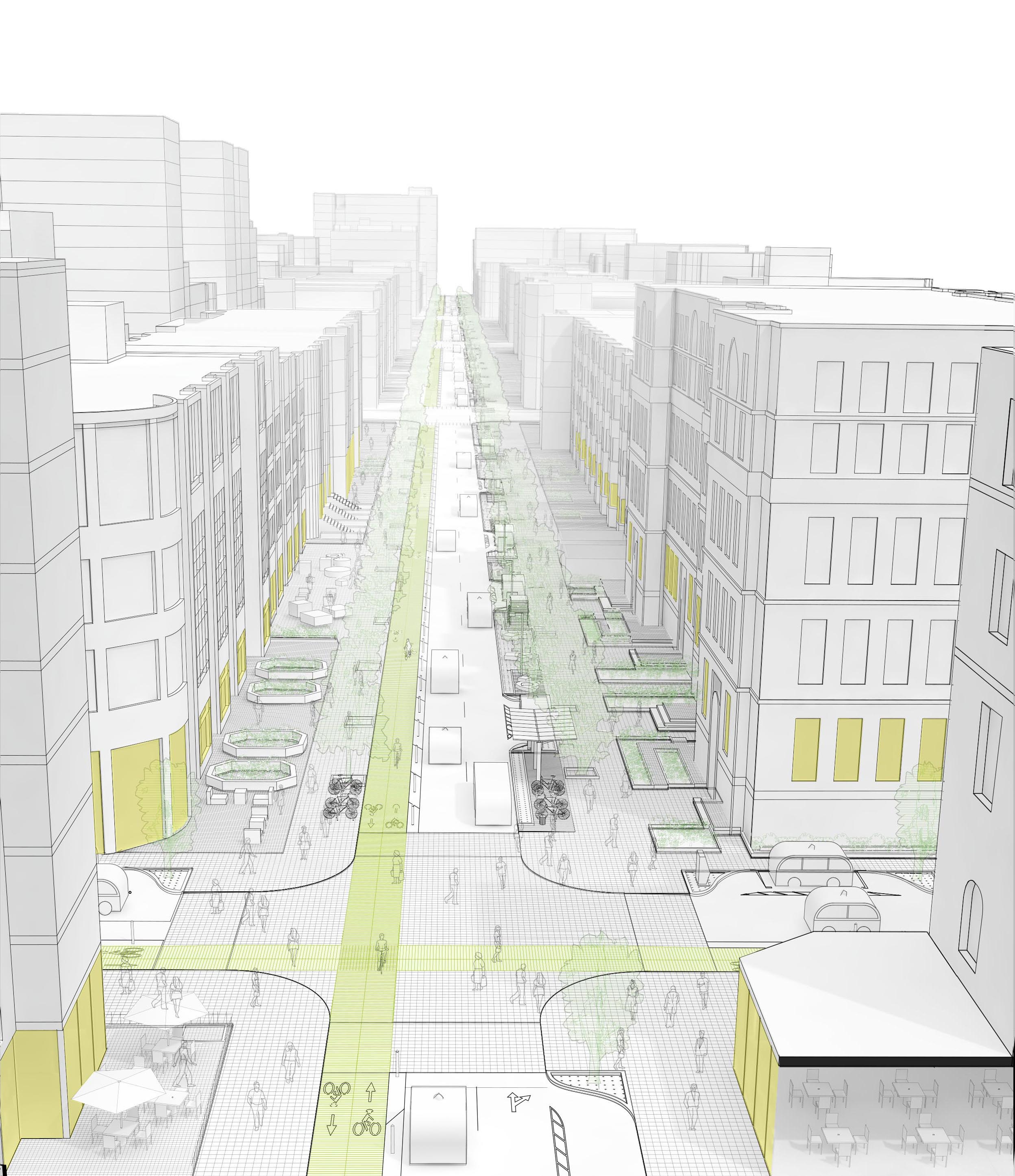

Future of Streets

The Future of Streets (FoS) research project at the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s City Form Lab investigates how cities might adapt streets to newly emerging shared, electric, and autonomous transportation technology in ways that maximize multi-modal, socially inclusive, and environmentally sustainable outcomes.

The project explores three key questions:

- How could new street-based infrastructure projects for shared, electric, and autonomous vehicles affect accessibility on other modes, particularly walking, biking, and public transit, as well as alternative uses of streets for social, commercial, and cultural activities and interaction?

- What impact could street modifications for new mobility technologies have on land values, residential displacement, and by extension, broader spatial accessibility to urban amenities, services, and resources among different socio-economic groups?

- What policy options, planning templates, and political strategies can help cities adopt new street-based mobility solutions so as to maximize multi-modal, socially inclusive, and environmentally sustainable outcomes?

Undertaken in collaboration between the Harvard GSD, the City of Los Angeles , the City of Boston , and industry partners representing technology, transportation, and infrastructure sectors, it comprises empirical research, spatial analysis, predictive modeling, and design studios.

For more information about the Future of Streets research project, please visit futureofstreets.com .

Global Design Initiative for Refugee Children

Global displacement has surpassed that witnessed in the wake of World War II, and children remain the most impacted victims. At least 3 million Syrian children under the age of six have been traumatized by war, and more than half of all Syrian refugees are under the age of 18. With the average stay of refugees being 17 years–for many an entire childhood–Refugees, Resilience, and Public Space was established in 2016 to facilitate the design and construction of space for refugee children and young adults living in temporary encampments to play and interact. On the surface, the initiative was to build a playground. In actuality, it was a first step towards developing a transnational, collaborative, and replicable process to design and construct child-focused spaces in the context of conflict or natural disasters. Building upon the work of humanitarians and peacebuilders who provide food, water, shelter, healthcare, and educational support, this initiative introduced child-focused public spaces to support positive interactions, social cohesion, and healing.

Download the Syrian Initiative Report (PDF).

“Global Design Initiative for Refugee Children” is the recipient of a 2020 Collaborative Achievement Award from the American Institute of Architects.

Urban Intermedia

“Urban Intermedia” argues that the complexity of contemporary urban societies and environments makes communication and collaboration across professional boundaries and academic disciplines essential. Each discipline produces its own forms of knowledge, but also has “blind spots” that can only be approached through other disciplinary frameworks. Those blind spots are the focus of the research and exhibition. Four city-based research projects in Berlin, Boston, Istanbul, and Mumbai form the core of the project and exhibition.

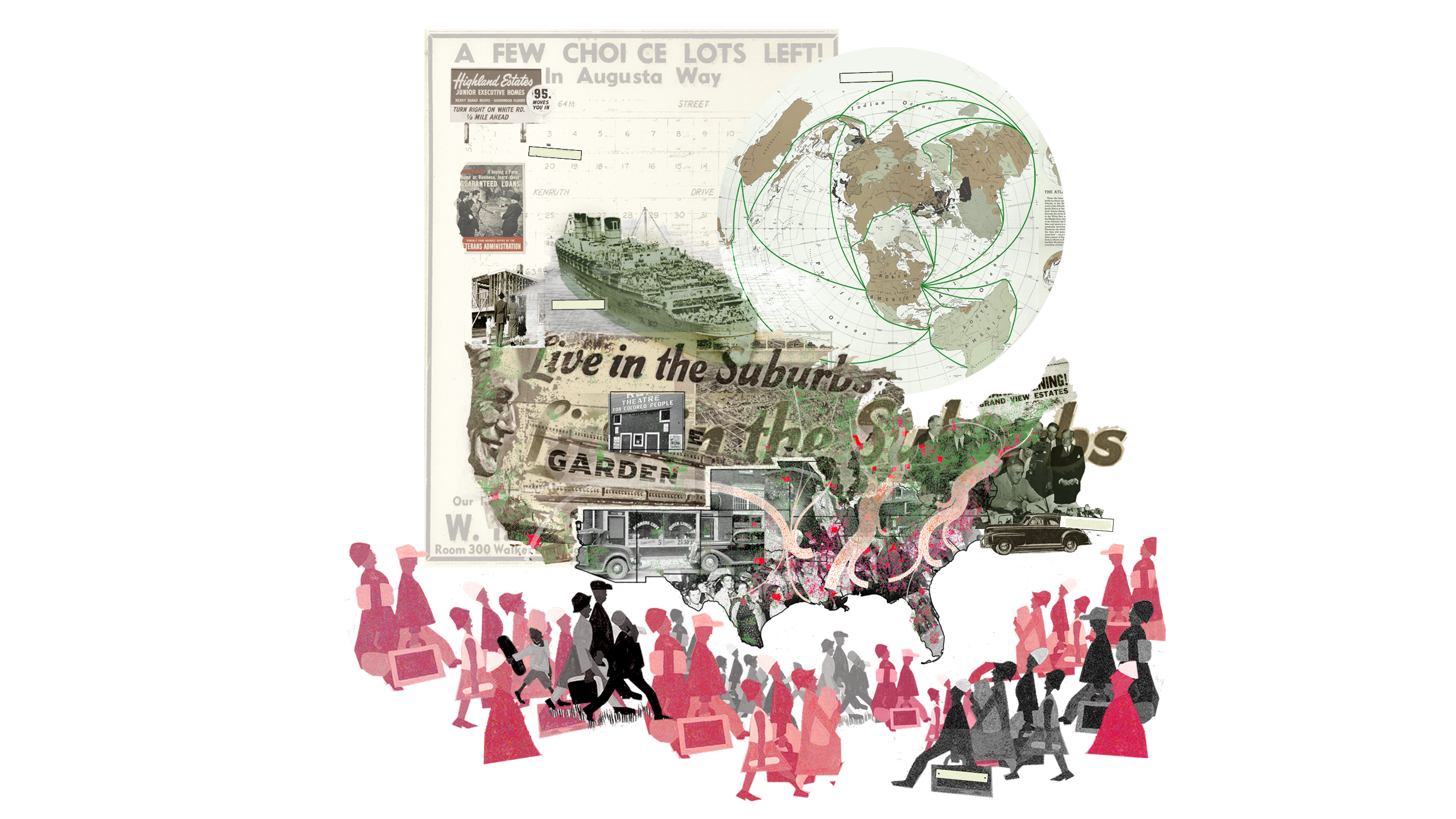

The theme for the Boston portal is “Race and Space”: cautionary tales about systemic racism. In the United States, urban projects emerge from collisions of competing interests and struggles over power and space, but also from racialized policies and exclusionary practices. In the urbanization of Boston, racism has been a persistent, yet insufficiently addressed phenomenon dominated by two recurring themes: pervasive racism toward communities not considered “white” (native Americans, black Americans, and most post-Puritan immigrants at various points in time), and tireless resistance to racism through community organizing and civil disobedience.

Between 1950 and 1980, federally funded highway and urban renewal projects swept through U.S. cities. National programs that promised to connect and rebuild crumbling urban cores instead systematically dismantled them, in the process disproportionately harming immigrants and people of color. These programs were designed primarily to respond to urban neglect following two post–World War II migratory movements. First, “white flight” saw white Americans moving to the suburbs, motivated by the promise of a better life and fueled by federally insured mortgage lending that chiefly benefited white veterans and steered them away from “red-lined” inner-city neighborhoods, which were predominantly black. Second, there was a mid–20th-century peak in the Great Migration of black Americans moving north and west to escape the Jim Crow laws of the Deep South and pursue economic opportunity. Many settled in segregated inner-city neighborhoods and, in Boston, were concentrated in a wedge-shaped area of the city where many black Americans and immigrants still live, experiencing dramatic disparities in wealth, educational attainment, and life expectancy as well as below-average access to jobs, open space, and public transportation.

While disparities caused by systemic racism are unambiguous in Boston, open discussion of the subject has only recently become a part of mainstream public discourse. The research presented here is intended to contribute to that discourse. It spans three eras of city-making and focuses on three physical infrastructures that define the spatial and political dimensions of the “wedge.”

“South Bay: Land-Making and Shifting Demographics” explores the interrelationship of migration and mobility in the shared histories of land-making, industrialization, mobilization, and immigration at South Bay, connecting industrial growth to immigrant influx and the early roots of Boston’s racist past. At the beginning of the 19th century, Boston embarked on a land-making campaign to support growing industries and meet housing demands. By the mid-20th century, the land area of the Shawmut Peninsula (home to the greater Boston metropolis) had increased 400 percent. In South Bay, the transformation was an incremental layering of shipping, rail, and highway infrastructures, and industry and housing fluctuated between serving two groups: working class immigrants and minorities, and predominantly white middle-class “Yankees” and “Yuppies.” This research exposes Boston’s manifestly limited progress in combating the effects of systemic racism over 150 years of housing development around South Bay.

“Southwest Corridor Park: Infrastructure and Community Power” explores the planned and unplanned impacts of racially insensitive public policies, community resistance to those policies, and remedial actions taken in the making and mending of Southwest Corridor Park. Federal highway expansion projects of the mid-20th century ripped through minority and immigrant communities across the country. In Boston, an Inner Belt connector was planned as the last remaining section of Interstate Highway 95, which would connect Florida to Maine (and, locally, Boston to Cambridge and Somerville). The project was ultimately halted by multi-city community action, but not before six miles of the neighborhood were demolished. Today, the Park is a reminder that celebrated urban infrastructures—including community gardens, playgrounds, bike paths, and subway lines—do not automatically improve the well-being of communities, especially if those communities are not true partners in their making.

“Columbia Road: Big Plans and Social Tensions” tracks nature and technology as oscillating drivers for urban growth. In the late 19th century, Frederick Law Olmsted championed an era of U.S. city planning aimed at mitigating the “harmful effects” of industrialization through park infrastructure. Boston’s most iconic public infrastructure, the Emerald Necklace, was designed to improve public health, support social cohesion, and drive market investment. But the Columbia Road section of the plan was never finished. With the city’s renewed commitment to completing Olmsted’s Necklace, the question today is, “Will Boston seize the opportunity presented by the Columbia Road project to empower communities, promote equity, and combat systemic racism through truly collaborative action?”

For more information about the Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative, please visit mellonurbanism.harvard.edu .

View the Animated Narratives .

Future of the American City

The Future of the American City project is an urban study initiative aimed at helping cities tackle urgent challenges. Building on the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s unique, multi-disciplinary model, the effort will use architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning and design to come up with actionable, efficient solutions that take into account community needs.

Research on Miami will form the first phase of the project, a broader initiative intending to also examine the cities of Los Angeles, Detroit, and Boston. The school plans to host a summit to convene experts from each city to create a national discourse on the future of cities and urban life in America.

To engage Miami residents in creating new approaches to address pressing urban issues—including affordable housing, transportation and sea level rise—the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation is providing $1 million in support to the Harvard GSD. With the funding, the school will embed urban researchers in Miami and Miami Beach to better understand the cities’ opportunities and challenges, and launch a multi-year study toward building solutions shaped by residents. Read the full press release.

Researchers at the GSD have been actively connected with the City of Miami and the City of Miami Beach for several years. Since 2012, the school has conducted six courses focused on Miami and held several major events in the city. Expanding on this work, the school will convene a range of experts, policy-makers, and members of the public to contribute to this new effort.

In its research, the school will focus on urban mobility, affordability, and climate change, themes that emerged from a series of previous discussions among its researchers and members of the Miami and Miami Beach communities. Following their analysis, students and faculty will offer toolkits, white papers, and other materials for review and use by city managers, mayors, and other civic leaders, many of whom will be directly involved throughout the study.

The research will be led by Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design, as well as Harvard GSD professors Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture, and Jesse M. Keenan, Lecturer in Architecture. The study will include a three-part series of courses being led at the school. This fall, a course will focus on mobility and transit in Miami, particularly Brickell, with a site visit in October 2018. A second course in Fall 2019 will examine the roles of higher education and medical institutions in Miami’s economy, and a third in Fall 2020 will focus on the roles of Miami’s various ethnic neighborhoods in shaping the city’s cultural identity.

Each GSD course will involve 12 graduate-level Harvard students and a professor working in a “design studio,” which involves conducting independent research, then discussing plans with fellow researchers to modify and strengthen their proposals. Each team of students will spend at least one week in Miami to speak with local stakeholders, civic organizations, and political and administrative leaders. Representatives from Miami’s civic and political organizations will provide feedback throughout the study.

Harvard Graduate School of Design’s upcoming Miami research is the first phase of its Future of the American City project, a broader urban-study initiative intending to also examine the cities of Los Angeles, Detroit, and Boston. The school plans to host a summit to convene experts from each city to create a national discourse on the future of cities and urban life in America.

Knight Foundation supports informed and engaged communities by identifying and working with partners to help our cities attract and nurture talent, promote economic opportunity and foster civic engagement. This effort will advance Knight Foundation’s work in Miami focused on building the city’s innovation ecosystem, while fueling entrepreneurship and new ideas. It will also help drive a national conversation about how communities can be more engaged in designing their cities to face the challenges of the future.

For more information, please visit the Future of the American City website.