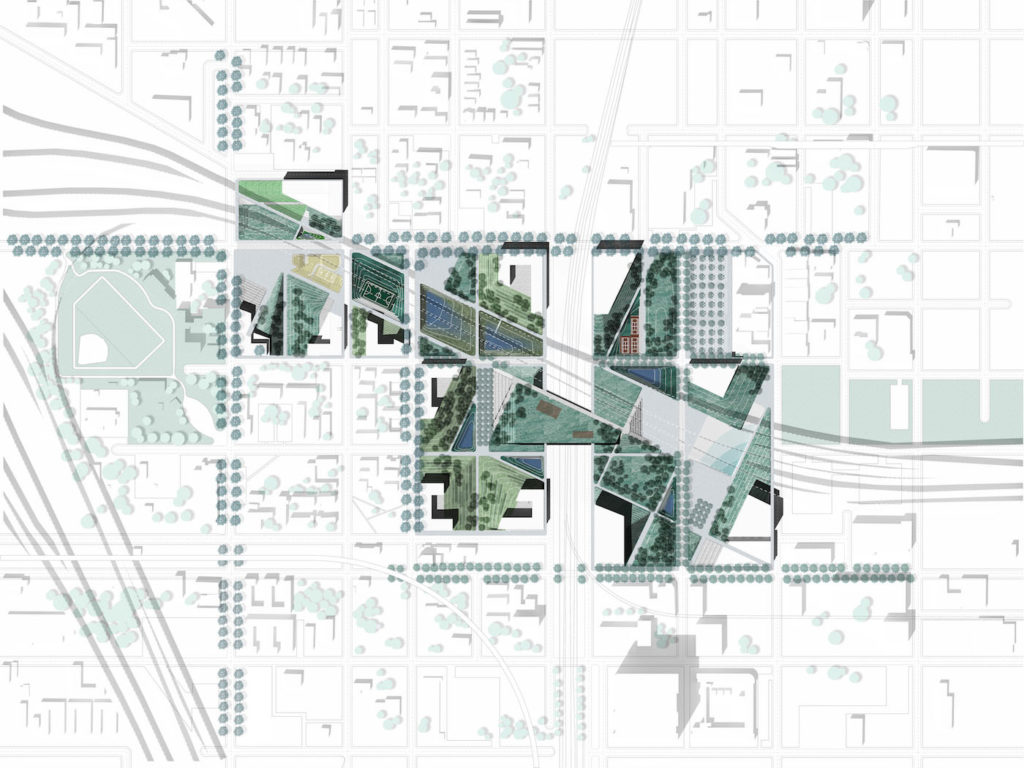

Across Racial and Infrastructural Boundaries: Integrated Park in Overtown

Chengzhang Zhang (MLA I ’19) and Qiaoqi Dai (MLA I ’19)

This project focuses on the Overtown neighborhood near downtown Miami. Overtown, also known as color town, once a vibrant black community, has witnessed high poverty rates, vacancy, and land speculation due to segregation by racial and infrastructural boundaries. This project proposes an integrated park, which embodies an urban strategy focusing on breaking boundaries and bringing investment for public in color town while avoiding gentrification. The project site locates on the joint of I-395 highway and the east edge of Overtown, as well as the historical color line and a freight railway. A new investment of a park on the site, proposed by Florida Department of Transportation as part of I-395 Highway extension, is unfortunately highly tourism oriented. Our proposal, on the other hand, reorients this investment to a continuous public park, which create physical stitch under the highway and over the rail between disparate parts of the community, fostering productive landscape and culture education as well as more than 600 affordable housing units as a revitalization of the community.

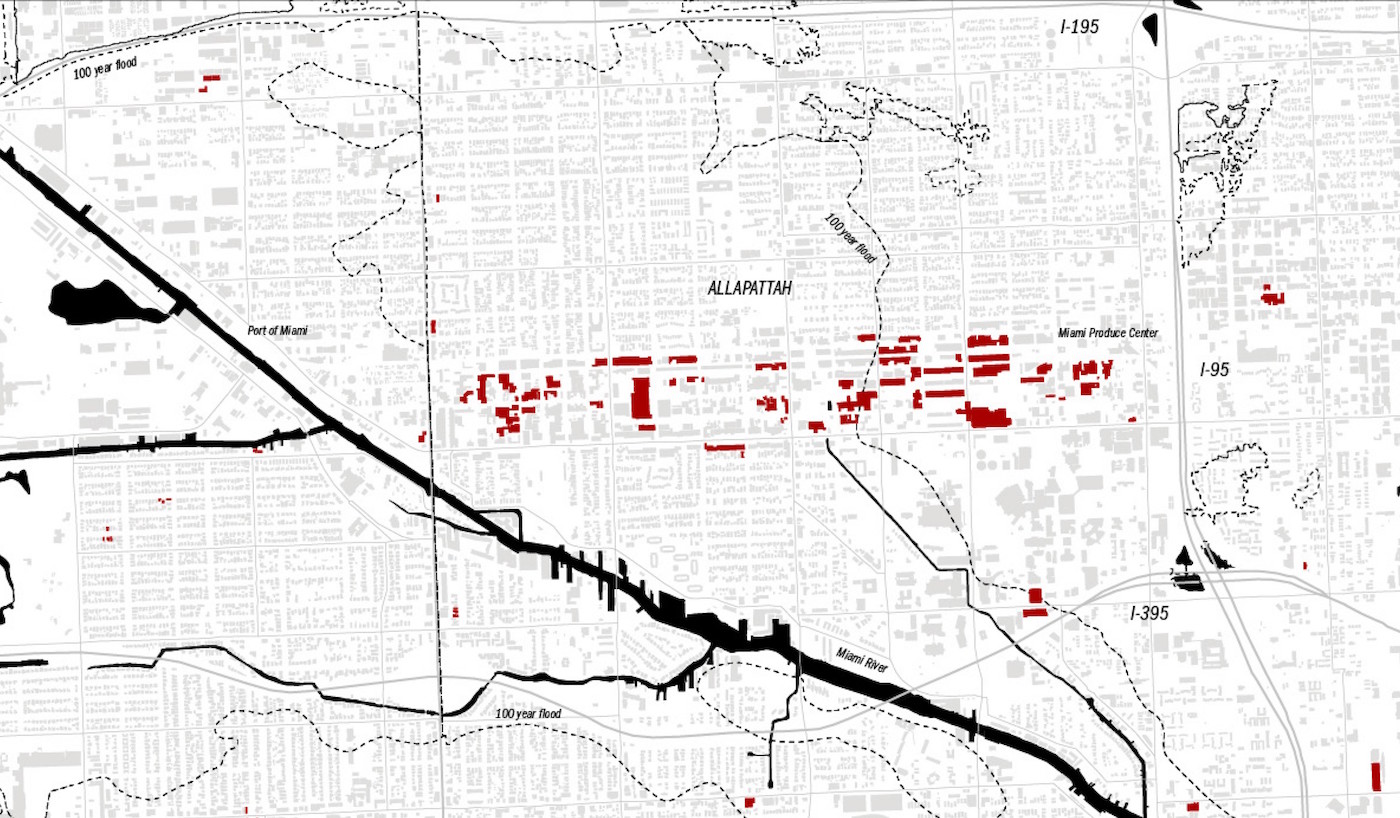

Food System Resilience: Addressing the Vulnerability of Miami’s Food System Through Distribution Cluster Centralization

Daví Parente Schoen (MLA I/MUP ’19)

Food distribution and processing in Miami is clustered around a number of hubs that have grown in response to market and infrastructural logics.These agglomerations are an integral component of Miami’s food system and vulnerable to increased risks due to climate change. This project proposes that state and county agencies create a food distribution hub in Hialeah or Opa-Locka that centralizes these critical facilities in order to increase resilience.

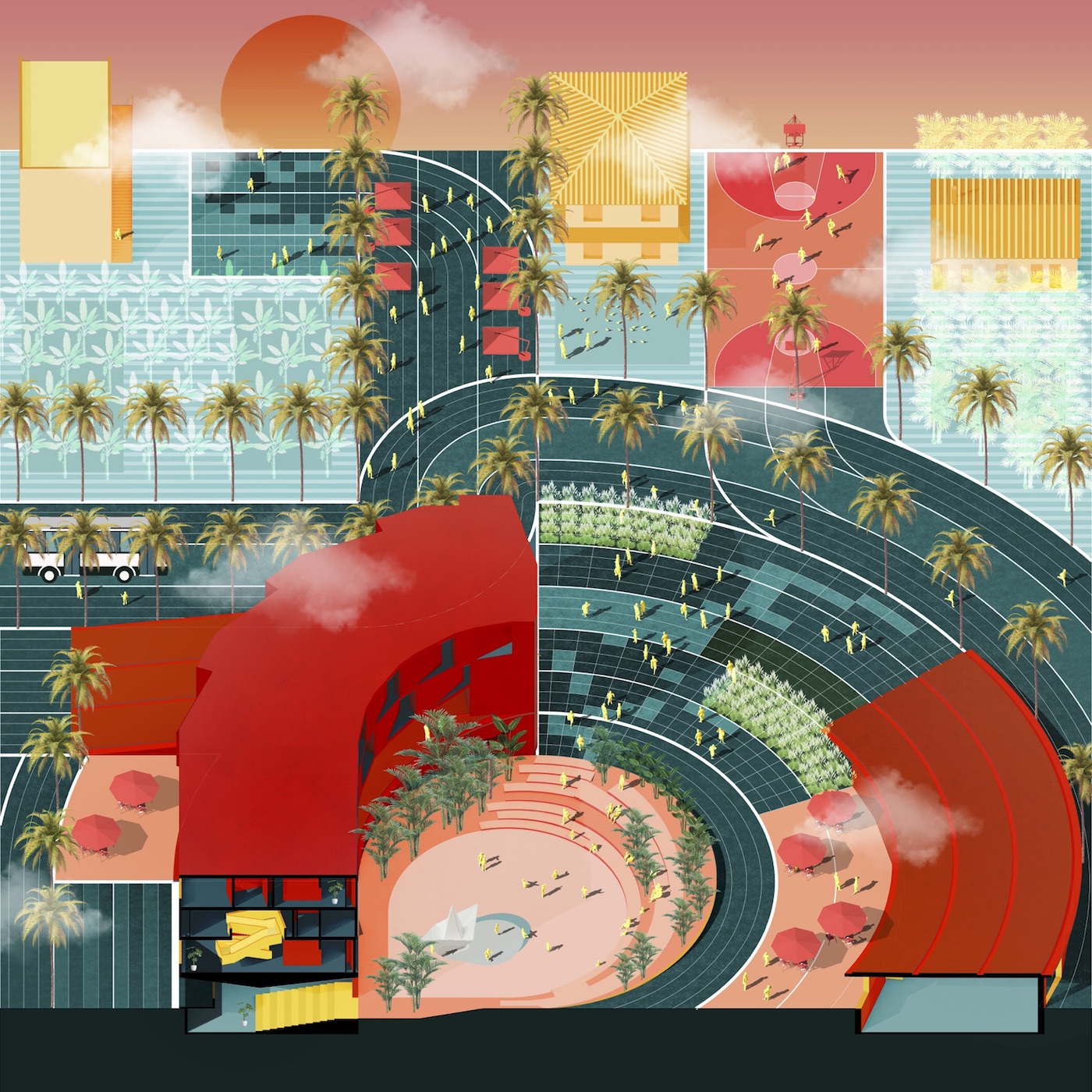

Food Sociability: Common Social Denominators

Evan Shieh (MAUD ’19) and Panharith Ean (MArch I ’20)

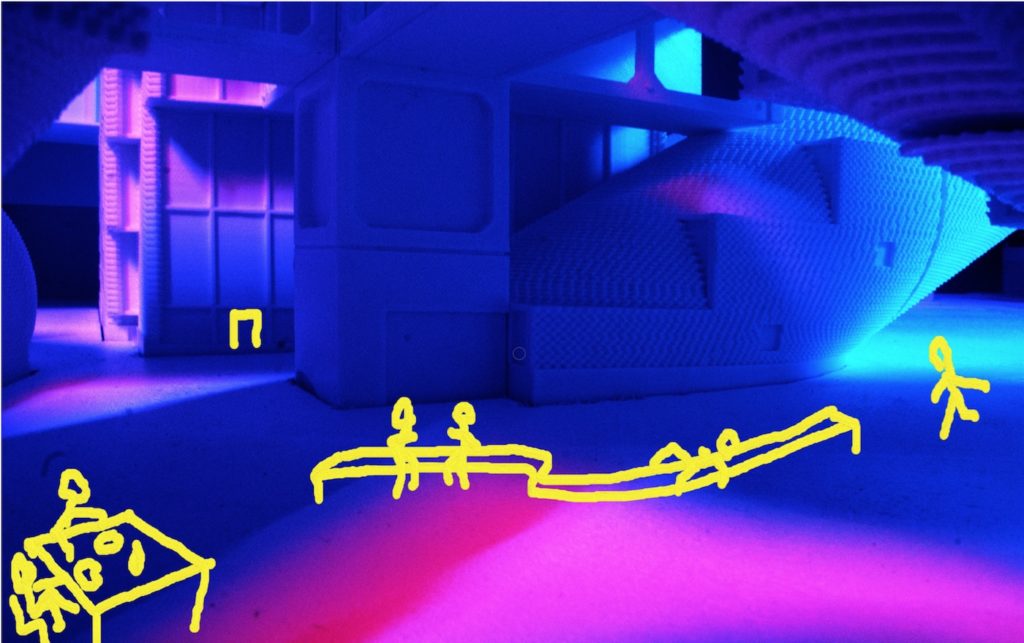

How do we design around the sociability of food and small-scale food production in the urban landscape as a catalyst for domesticity and communal living? This project is instigated by what might be termed the “common social denominator” of food and the sociability around eating together, gardening together, and living together, activities that bind us as humans. The project instrumentalizes the spatial sociability of food as the foundational building block to critique and intervene tactically in three typological sites, each representing a different ownership model.

In the first site, the private single-family suburban block is co-opted with the introduction of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU’s) that are tactically inserted into the backyards of existing single-family dwellings in order to increase density and provide additional rental income. In this model, previously underutilized side and back yards are activated by communal gardens and fruit trees while micro-openings in existing dwellings create sociability between neighbors.

In the second site, a publicly-owned affordable housing mega-block is critiqued with a new block typology that inverts typically outward-facing porches towards the interior of the block. New interior-facing porches are reconstituted programmatically with communal kitchens and outdoor dining while porous block interiors are activated by greenhouses, community gardens, orchards, and recreational sports, anchored by guardian institutional community centers and corner restaurants.

Lastly, an existing commercial/cultural corridor in the district is reinforced by inserting extensions to existing restaurants and grocery stores, new retail and farmers markets on vacant lots, and even housing additions when density is needed.

In totality, the three sites represent an opportunity for tactical urbanism catalyzed by food sociability and food production, design strategies that spatialize and build upon the existing robust culture around food in the district of Overtown and the city of Miami at large.

The Ephemeral City: Productive Urbanism

Ting Liang (MLA I AP/MAUD ’19) and Zishen Wen (MLA I AP ’19)

Our project re-choreographs the physical fabric of Overtown, allowing for expressions of multiple identities through a series of new typological strategies of “Ground” and “Figure.” The project sets up an urbanistic framework which embeds the possibilities for changing, providing numerous ephemeral moments, creating an urban setting that is constantly engaging in the process of scripting and re-scripting itself while always open to next phases. The choreography of the places responds to the multiplicity of social impulses and social needs both from the existing and potential new communities. While there is specific timeframe, there is also no timeframe. The scale of interventions is initially subtle, but gradually implies systematic moves with more ambitious and radical changes, which overall inspires a projective future of new urban living that energetically engaged with social and environmental dynamics.

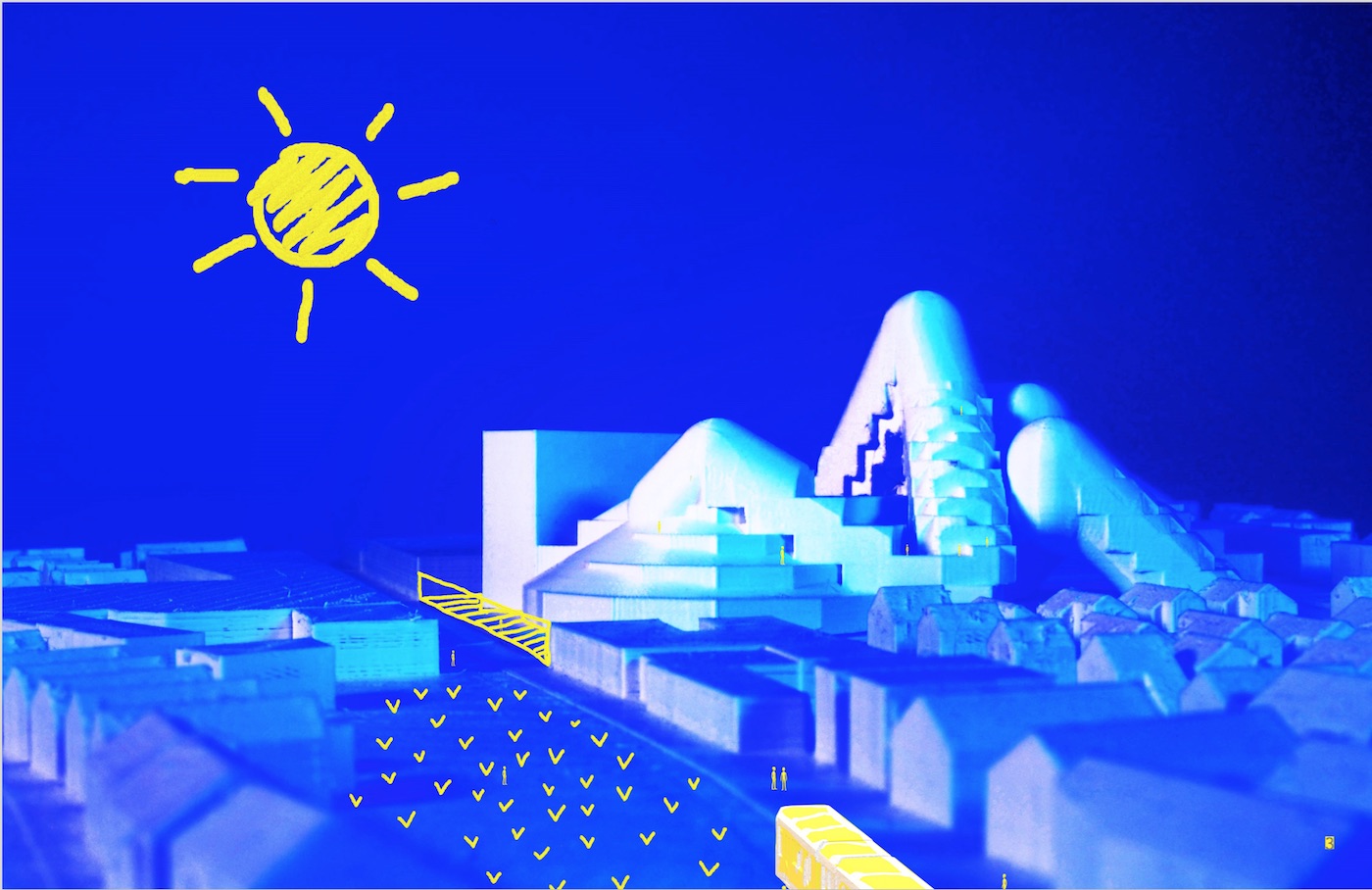

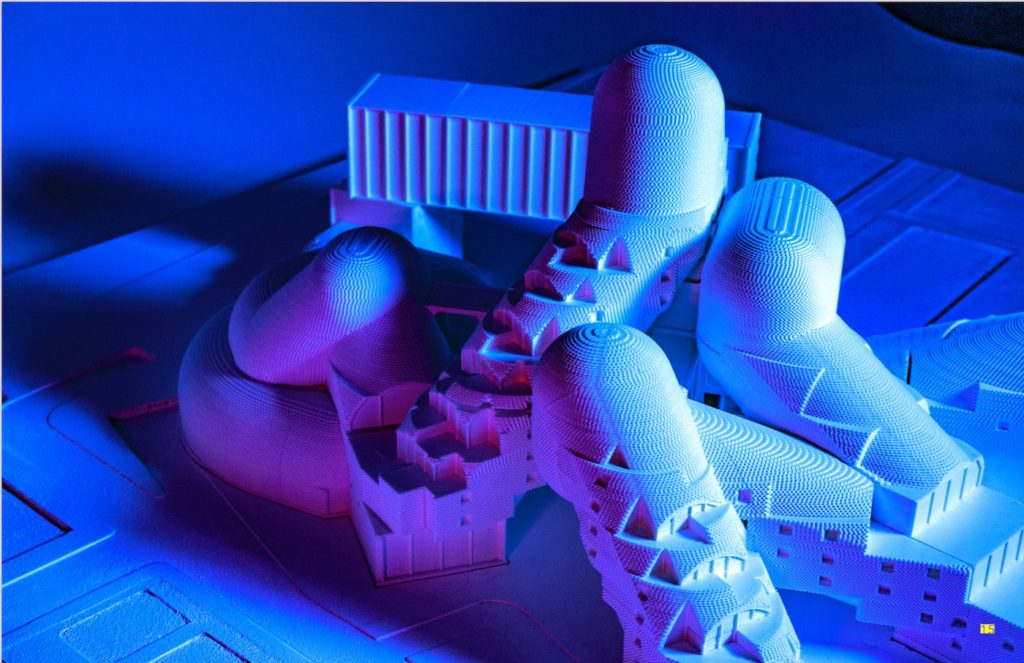

A Giant Among Us

Son Vu (MArch I ’21) and Alex Yueyan Li (MArch I AP ’21)

It is hard to get in and out of Somerville, and true public spaces are few and far between. Though several nodes do exist, these piecemeal developments are often solely commercial enterprises. Furthermore, Somerville’s residential identity is tied to triples-deckers dotted among low-slung homogenous areas. Under existing conditions, the kind of dense and unpredictable urban quality—whether it be effects, experiences, or the buildings themselves—cannot be much lived. This project interprets the urban condition as a line strewn with points of interest. Our ‘line’ is quite literally operated on—by stretching, twisting, and rotating, at the building scale. We first began by thinking through ways to mitigate the ground level. We negotiate the understood existing boundaries by stretching elements out to touch on key edges of the site, continuing on the rhythm of existing buildings. Within this thickened at site’s edge- line are shops, restaurants, and cafes; and within the agglomeration of these shops and stalls, lobbies and unit entrances are camouflaged. As the ‘feet’ of our line touch ground, they are spread out enough to make the boundary porous—a dashed line which allows physical and visual connections through this giant.

The line leans in onto itself to create a mountainous form made of residential units. This process of residential self-formation carves out a cavernous space for the various mixing of events, resulting in spaces which may accommodate seasonal, sponsored, or informal activities such as Porchfest or perhaps an evening film projection. These events may be deeply rooted in Somerville’s social tradition, but rather generic ones can also be accommodated for. There are four unit types engendered by the angle of line’s lean. Corresponding units offer a selection of living types and styles that relates to density, vertical circulation, usable floor area, and opacity among neighbors in varying ways. From shallow to steep, the living arrangement shifts from public to private, communal to individual: live-work, artist commune, multi bedroom, and single bedroom. Different housing bars intersect, and housing types overlap, bleeding into each other as shared areas which reimagine collective living: communal cooking, dining, relaxing, creating, working, playing all arise from these bars’ agglomeration. From the outside, the project is a megastructure not unlike super-form; but as the building performs, key elements nurture flexibility above any specific program or use. Perhaps daunting at first glance, the form draws one in—a friendly giant.

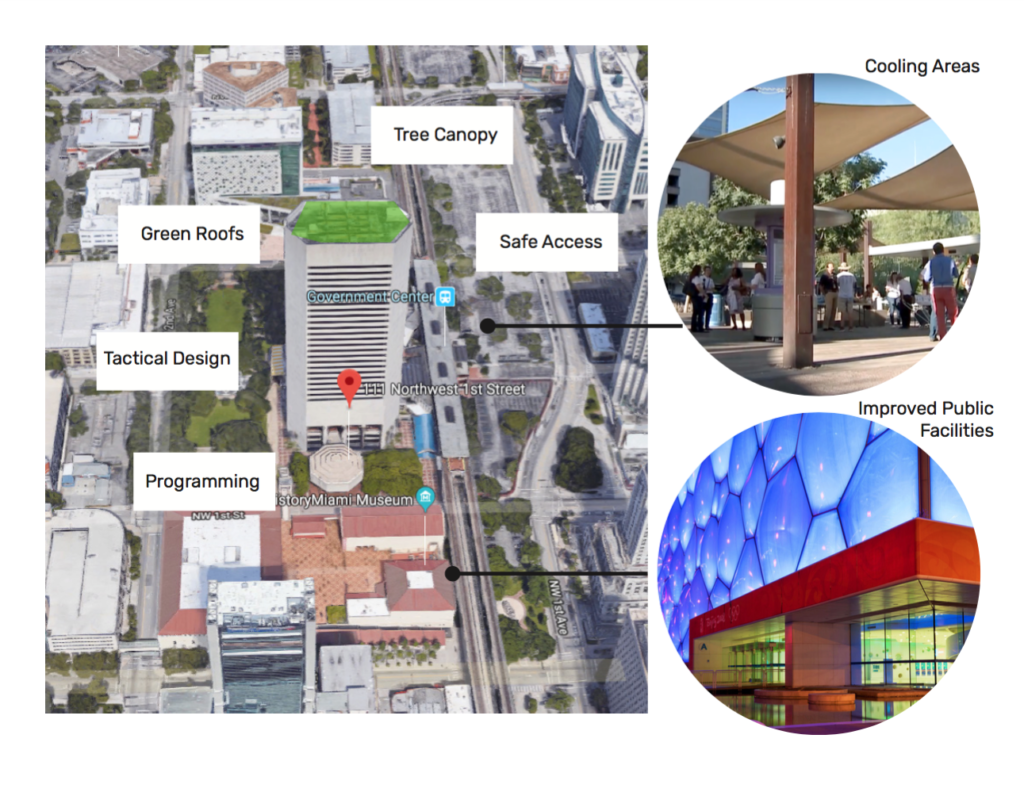

Climatic Crime

Cesar Castro (MUP/MDes ’19, Risk and Resilience)

The aim of this analysis will be to understand not only how crime may be impacted by climate change, but what specifically can planning and design contribute to a city’s effort to curb the impact of such environmental exposure in the short and long-term. Using the City of Miami as the primary site of investigation, this analysis will draw on long-standing research regarding the connection of crime and the built environment and the potential internal migration of people within the City of Miami to assess how concentrations of crime may shift overtime in low income areas. Central to such assessment will be a theoretical understanding that crime prevention, whether physical, legal, social, or otherwise, must include elements of community input and development in order for it to be truly comprehensive and ready to tackle the multidimensional challenges and opportunities of climate change, environment exposure, and crime for already vulnerable communities and in particular those that are least mobile.

Flamingo Waterpark

Izgi Uygur (MLA I ’18)

In subtropical climates such as Florida’s, there is either too much water or not enough water. It is a place of extremes, as well as a region confronting changing climatic conditions and highly stochastic weather patterns. This project balances freshwater availability seasonally by defining the effects of increased salination on varying types of water due to sea level rise. It is possible to address the freshwater shortage by using a series of stormwater retention tanks in Flamingo Park.

As the only large and open landscape in the city, Flamingo park can address two hydrological issues: the fluctuation of freshwater availability and the threat of sea level rise, without drastically changing its existing character. This helps not only to save energy and water by decreasing the stress on desalination facilities, but also supports the governmental plans of increasing green spaces by irrigating park’s native and aesthetic vegetation. Instead of elevating the entire park, this scenario proposes to place the tanks on an altered topography above the projected flood lines, where the landforms also offer dry ground for post-storm relief.

This project imagines strategic interventions that makes the park a part of the municipal infrastructure. An underground network of pipes that connects the tanks within the park can not only help to irrigate the park trees, sports fields and alley trees, but also the green spaces around the park. Overall, this can contribute to individual irrigation and vegetation control. In addition to its role as added infrastructure and public space, the elevated cisterns introduce a new ground for varied botanical landscapes and suggests a new future for the park that combines city’s history of botanical gardens and its planned sea level rise adaptation.

Read about this project in The Miami Herald .

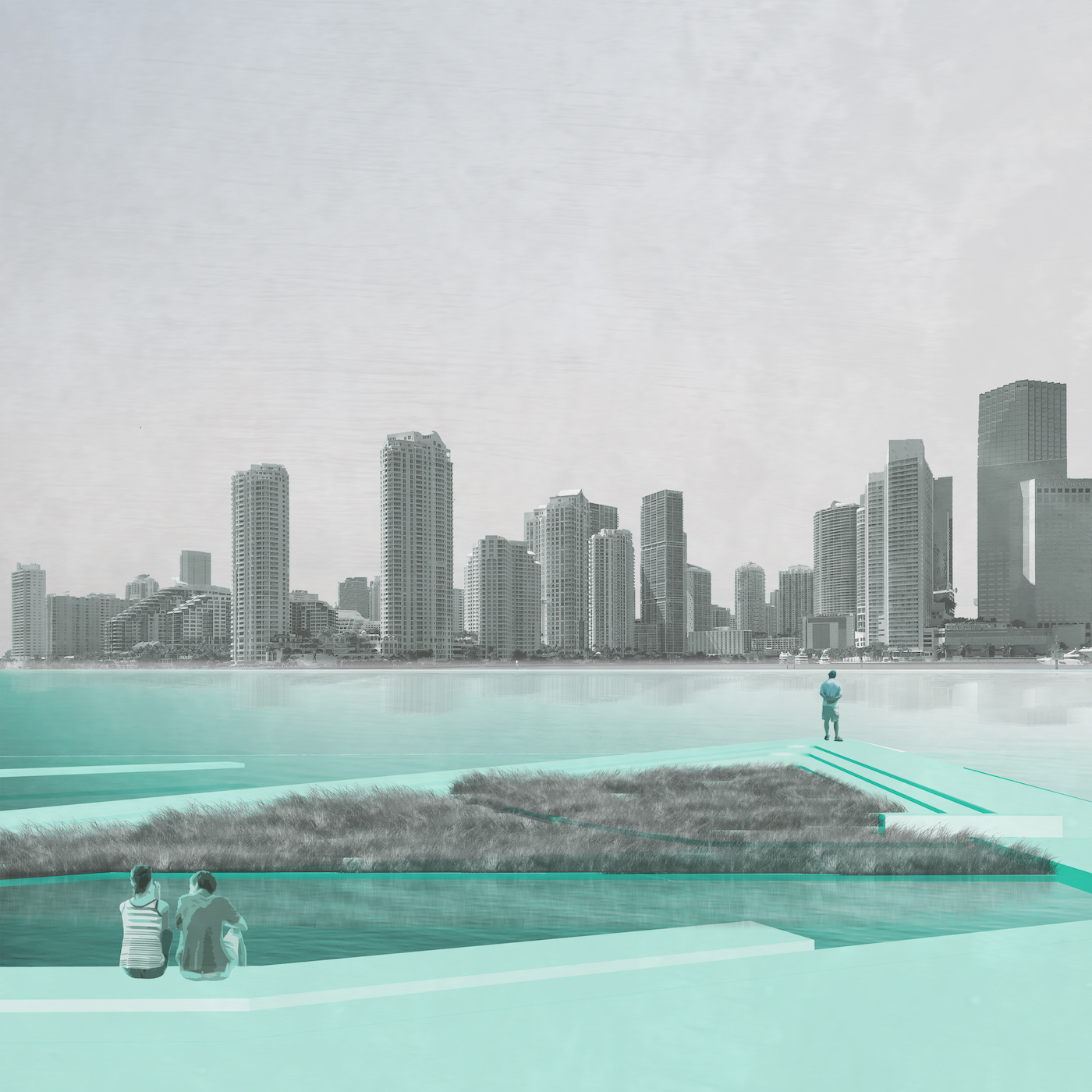

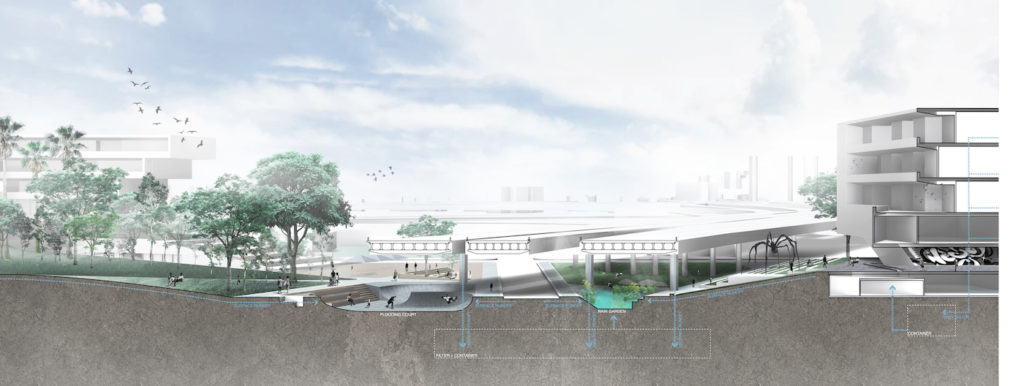

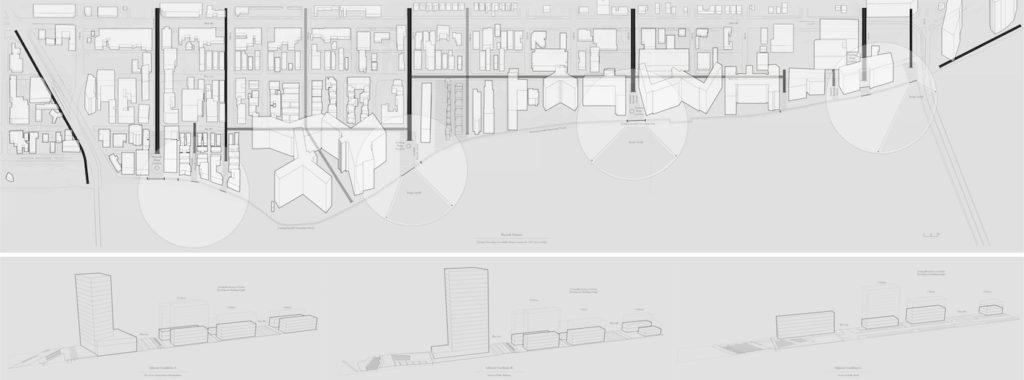

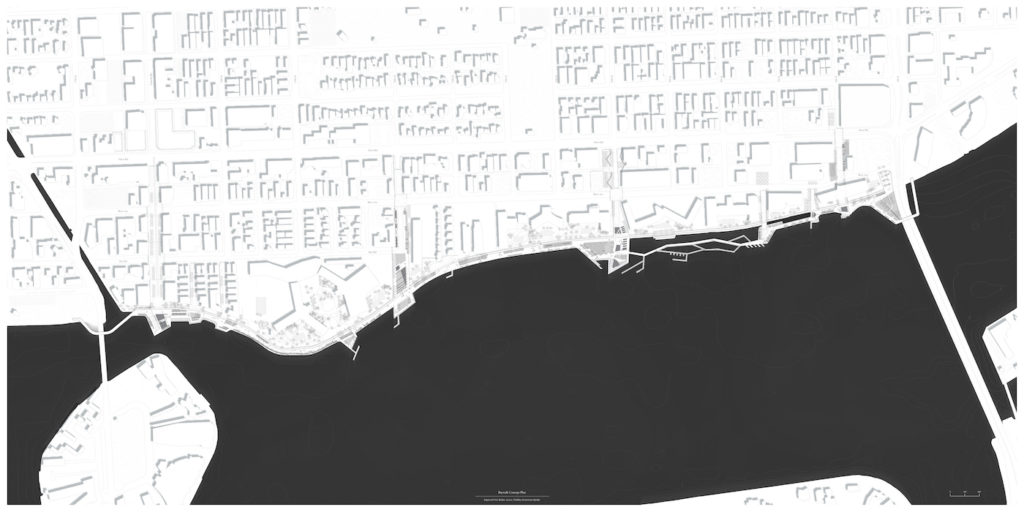

Miami Beach Baywalk

Chris Merritt (MLA I ’17)

The Miami Beach Baywalk will serve as an infrastructure for storm surge and stormwater quality while functioning as a new public space for Miami Beach. Sea level rise projections indicate the Bayside is the most vulnerable on Miami Beach. In addition, as this area has the lowest elevation, the city’s stormwater naturally drains and is pumped to the Bay. Recently, the City of Miami Beach has installed pumps along the Bay to handle the pressures of large volumes of stormwater runoff. The new Baywalk is designed to alleviate stormwater quality issues while enhancing the quality of the public realm. The Baywalk will serve as a continuous, connected, and visible system of plazas and walkways that return the Bay as a destination to the city.

Background

The emergent topic of urban adaptation to the effects of climate change is among the more pressing areas for those engaged in the design of the built environment. Among the more extreme cases in this regard is the present status and uncertain future of South Florida’s coastal communities. In Miami Beach, the low-lying coastal conditions and singular cultural heritage resist the types of massive civil engineering projects that have recently been proposed for other major international cities. As Miami’s coastal barrier islands form one of the most recognizable and singularly valuable cultural landscapes in the world, the conditions in Miami Beach reveal the potential for ecological and infrastructural strategies to act as alternatives to large single purpose engineering solutions. Today, the structuring elements of urban form in Miami Beach are quickly becoming the pumps, seawalls, road elevations, artificial dunes, and sacrificial floors that are deployed in response to rising sea levels and increased storm events. How can designers act and what is the role of the landscape architect in this urgency for urban adaptation?

Miami Beach is a construction. It was drained, defoliated and developed through the promotion of its climate; perfect temperatures, ideal beaches, seamless horizons, warm water, and unencumbered escape. The porous oolitic-limestone that underlies Miami Beach makes the city particularly vulnerable to sea level rise as seawalls are simply ineffective, and multiple pumps are only temporary measures that help municipalities cope, but not adapt. With the pending dimensions of sea level rise, water has become a threat, as it is generally accepted that Miami Beach will be subject to rising waters and flooding – not to mention potential devastation from incoming and worsening storm tracks. With the conservative estimate of a 2ft rise in our oceans by 2060, Miami Beach will be underwater and Miami shorelines will recede up to 2,000 ft. (National Climate Assessment Data). While hard infrastructure, raising roads, and proliferating pumps are managing the issues and allowing the city to cope, the prospects and opportunities of future scenarios remain unknown.

Urban adaptation to ambiguous sea levels is creating a new form of public space, and the application of resilience as a measure of success must respond to and address these new public parameters. Given the reliance of South Florida’s economy and identity upon the specific landscape conditions of Miami Beach, this project proposes to use green infrastructure, landscape ecology, and cultural heritage as potential responses to the looming threats associated with sea level rise.

Project Description

A cross section through Miami Beach reveals a slight slope from the nourished ocean-side beaches and Ocean Drive down to the Bay. As the commercial back-bone of the city and lowest in elevation, this area is Miami Beach’s most vulnerable, and current target for intervention by the City. The natural topography and recently installed pump infrastructure carries the island’s stormwater to the Bayside where it is pumped back to the Bay. Through the aggregation of private condo development common to Miami Beach, a wall has been created that separates the city from the Bay with limited access. The proposed Baywalk project outcomes are threefold: 1) introduce an infrastructure for managing stormwater quality, 2) mitigate effects from storm surge, and 3) renew the public realm with access and visibility to an ecological and culturally vibrant landscape.

The proposed new Baywalk is a continuous linear public space connecting Miami’s South Pointe Park via the 5th Street Causeway to Maurice Gibb Park to the north. The Baywalk also reaches back into the city, literally and figuratively, utilizing City owned parcels and streetscape improvements to provide better access and visibility while managing stormwater before it reaches the Bay. Previously, private condos along the Bayside have fragmented the Baywalk – leaving no connections between each development. In addition, with the introduction of new pump infrastructure at the Bay, an opportunity exists to leverage this system for a model of urban adaptation to sea level rise.

The framework of the Baywalk starts with recognizing an opportunity for increased public space exists at each of the existing and proposed pump station locations. These locations are utilized to bring stormwater runoff from the city through a system of separation, filtration, and aeration before releasing water into the Bay. The Baywalk is not just a utility; it also enhances the public realm experience. The pump station locations are transformed into large plazas for gathering that are distributed evenly and provide a unique experience along the Baywalk. This new public space exists at the terminus of Lincoln Road, 14th Street, 10th Street, and 6th Street. The plazas are linked together through a linear Baywalk that removes the existing divide between private and public.

The condos along the Bay in Miami Beach sit on a podium filled with parking that creates a wall along the fragmented Baywalk. In some cases, the buildings have a simple retaining wall separating the Baywalk from the private terraces of the condos. This condition creates a separation that reveals the sharp contrast between the private condos and the minimal Baywalk – “the haves and the have-nots.” The proposed Baywalk joins the two spaces creating a seamless public realm that transitions from building to water through a series of terraces, slopes, walls, and landscape elements.

Miami Beach is a place for people watching and sun bathing; and for recreation and relaxation. The currently underutilized Baywalk is transformed into a public promenade where one can see and be seen. Utilizing the necessity for elevation change, varied experiences are created and rooms are carved along the Baywalk for smaller gathering and intimacy. With retail, dining, and entertainment, the Baywalk serves as an extension of Lincoln Road at the Lincoln Road plaza. And, by removing the divide between public and private and offering new access, the Baywalk serves locals in Flamingo Park. The extension of the Baywalk back into the city fabric offers visibility and a physical connection that ensures the Baywalk is built for everyone.

South Florida attracts residents and tourists alike for its subtropical climate. Combinations of unique species of flora and fauna are found in this geography that cannot exist elsewhere. In addition, the Bayside of Miami Beach was historically home to thriving marine habitats before the introduction of anthropogenic pollution and destruction. Therefore, the Baywalk is designed to accommodate habitat development for its ecological function and cultural significance. At each of the stormwater management plazas, vegetation is selected for its utilitarian function. In other areas, a cultural abstraction is utilized to create a “marine museum” or “ecological museum” that serve as a cabinet of curiosities along the Baywalk. Vegetation zones include pineland and hammock planters, temperate and tropical assembly gardens, a beach with an artificial dune, and linear mangrove habitats. The “marine museum” includes boardwalks through sheltered pools that enable stable habitats of seagrass, coral, sponges, and wetlands.

Through proactive measure Miami Beach can respond to the threats of sea level rise with opportunistic infrastructural intervention that also enhances the public realm. In a challenging political climate and market with increasing private interest, the City has to be strategic about investment in the longevity and quality of Miami Beach for the public good. A new Baywalk that manages stormwater quality, protects against storm surge, and enhances the public realm is a boon for visitors and residents of Miami Beach alike.

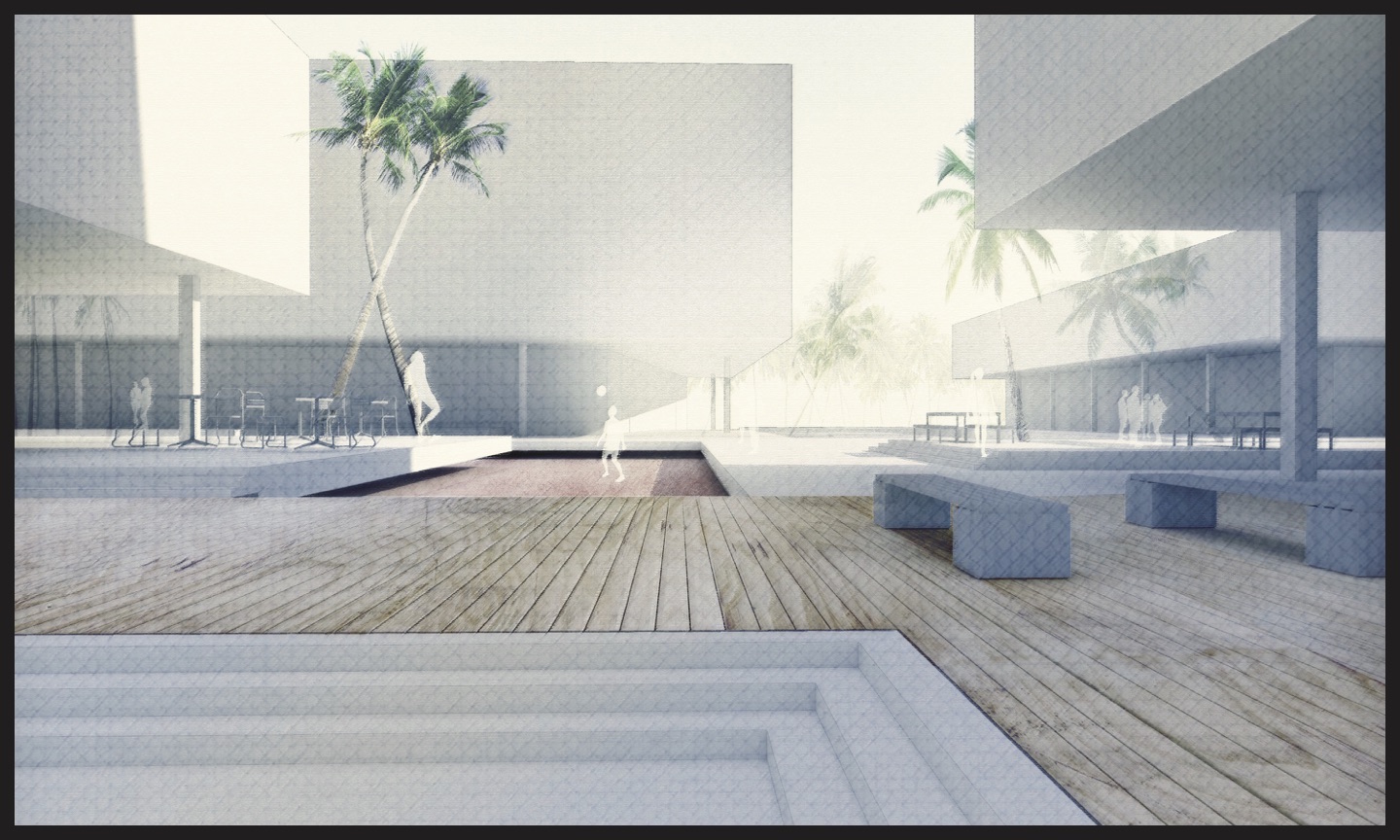

Ocean Court

Daniel Widis (MLA I ’16)

Tenuously positioned as an informal slip of sand and coral limestone, Miami Beach has been formalized into a rigid, urban landscape through decades of commercially driven development. The end result is a city devoid of genuine public space. When expressed, public space lands in the artless form of linear spaces running along beach-front properties. The inherent tension between public/private, formal/ informal is best expressed in these linear landscapes – spaces that are framed as pedestrian and civic, but at their heart are unapologetically commercial. The inevitability of sea level rise offers an invaluable opportunity to reclaim and animate the city’s largely forgotten public realm. Ocean Court revitalizes a neglected interstitial alleyway in a city desperate for functional community and civic space.

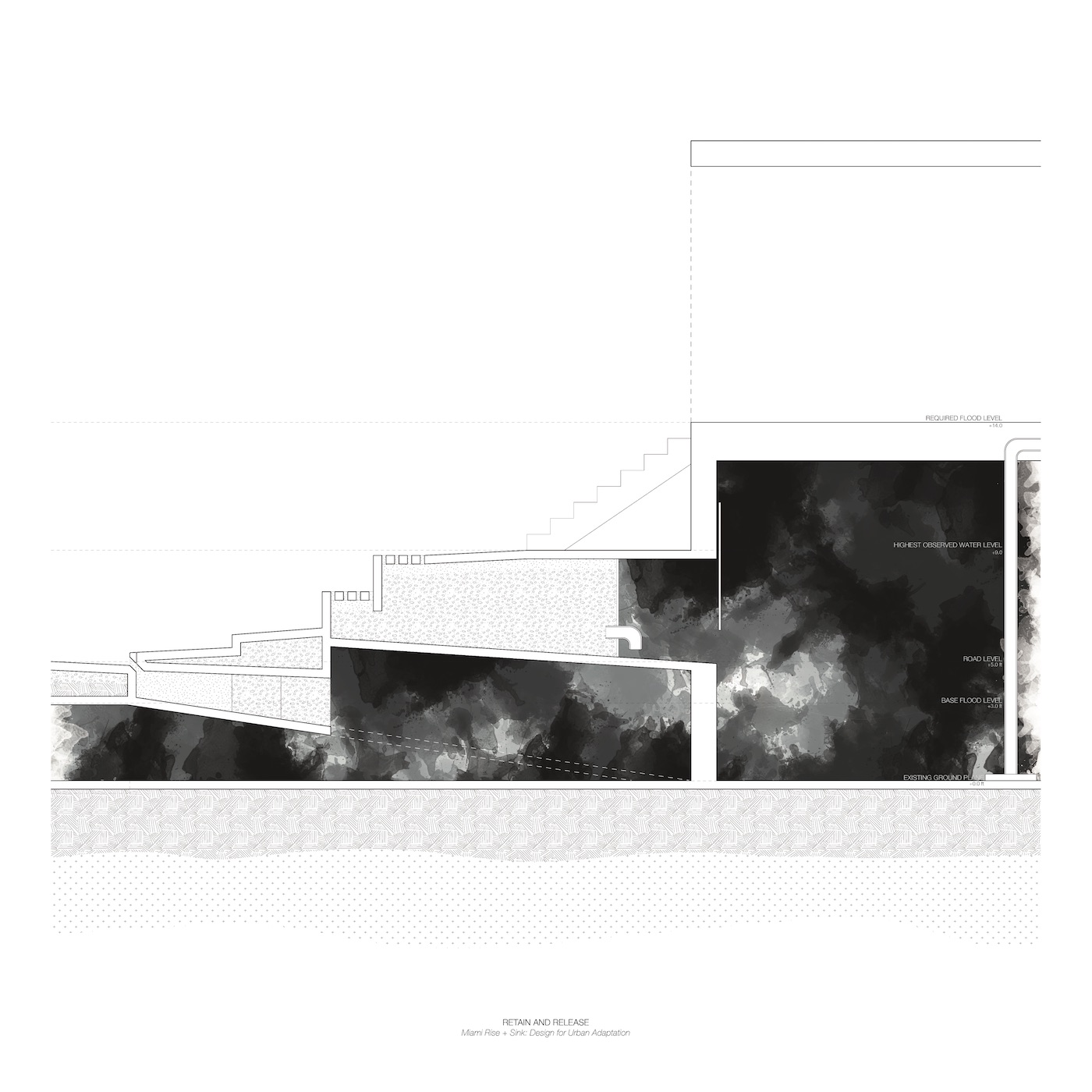

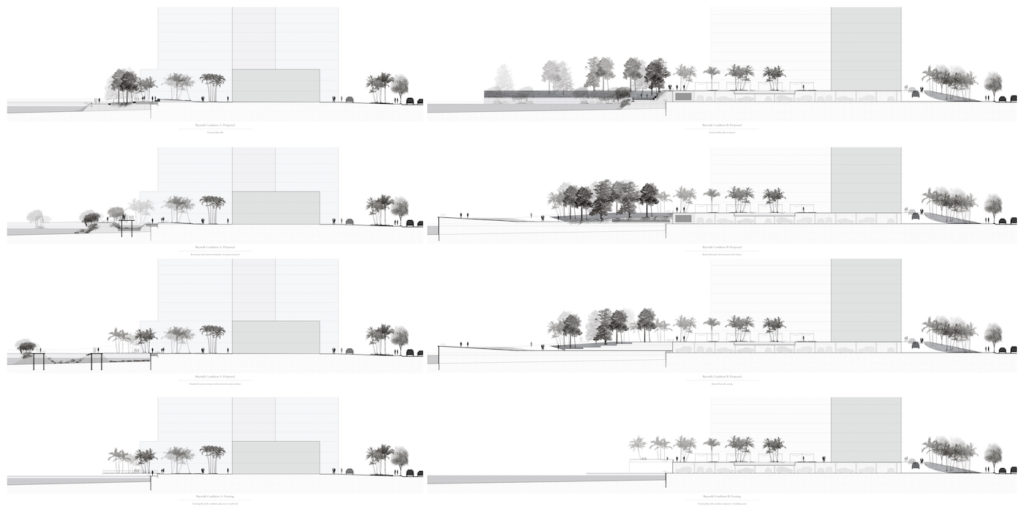

Higher Lanes and Public Planes

Myrna Ayoub (MArch II ’16)

As sea-levels rise and the threat of flooding looms within South Beach Miami, new regulations and codes are responding through recommendations to elevate the city. The proposed flood level floor and raised roadway are an adaptation of elevation–a deliberate re-articulation of the ground-plane that creates a new urban threshold. By reworking these modifications, water can be absorbed, moved, or retained as opposed to shed, concealed, or pumped. The fluctuation of urban boundaries, manifest in the section in particular, reveals an exploration of levels that augment civic context. This project explores the potential manifestations for these new elevations through the study of three sites identified along the transect of 4th and 5th avenue. The typologies negotiate the parameters and accommodate the existing urban conditions to allow for the preservation of a dynamic/heterogeneous city and the resilience in the face of rising sea levels through the exploration of the urban section.

Hydrologies: This project explores section operations to maximize municipal stormwater management capacities. In the public realm, streets elevate with limestone-like fill to increase storage. New pervious ground cover materials slow runoff from overburdening existing drainage systems. In the private realm, new ground floors sit atop limestone filled “sponge pads” and elevated buildings cede ground to maximize sheet flow. In both realms, additional vegetation and their deep urban soils add stormwater infrastructure.

Spaces: The interior of the site is set aside for ecological performance. Low-maintenance native ecosystems are fostered to regenerate potential habitats and reduce open-space maintenance fees. Concentration of tree planting at the northern and southern tips suggest public parks and possible habitats that could spur from the alluvial channel. Topographical modifications foster the succession of native species. East-West corridors enable street tree planting schemes that organize and orient the block structure.

Infrastructure: This scenario views ongoing engineered infrastructures as a multi-layered system that provides pubic benefits and a new urban landscape. In addition to elevating the street roughly 5’ above current grade, mass transit is also introduced along 5th Street where it connects directly to the MacArthur Causeway. Pedestrian walkways and bikeways take precedence over vehicular traffic which is reduced in capacity and speed. Certain parts of the new ground plane are reimagined as extensions of public space.

Policies: Coordination between the public and private realms is paramount to creating seamless urban thresholds and transitions. A finer-grained zoning overlay map would be necessary to integrate suggested common flood elevations and regulate private properties to match such elevations. Where roads cross multiple jurisdictions, additional cooperation is necessary to ensure the successful design, construction, and maintenance of proposed section scenarios. FAR incentives on key corner properties would help initiate and accelerate their adaptive redevelopment.