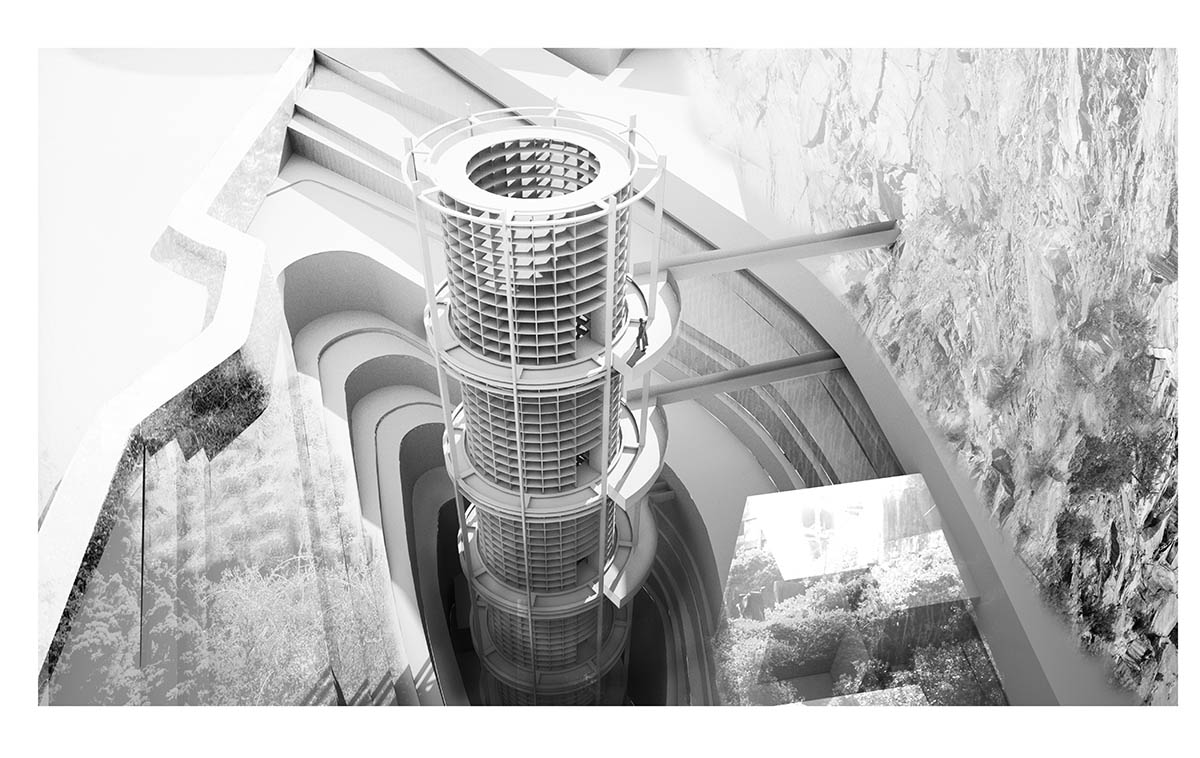

“286 South” and the Essential Role of Architects

Benjamin Halpern (MArch I ’17)

This project is not about universal housing or good-for-society housing—the types that typically win such awards as the Clifford Wong Prize. This project is about super-luxury housing.

Yet this project is also about “the essential role of architects”—to design with creative agency for housing of any type. And thus, this project should be judged not only by what it does for the specific inhabitant, but also by what it does for the discipline of architecture.

Context

Over the past decade in New York City, aggressive and creative real estate developers have seen a window for profit in very tall, very slender residential buildings that offer spaciousness, exclusivity, amenities, and, above all, spectacular views. This new typology of pencil towers induces in me equal parts amusement, enticement, and distress, as architects have been reduced to brand-name service providers.

We as architects—and I mean critical architects, especially in the academy—have two options: turn our backs to the entire practice, or accept it as a superlative reality of late capitalism and design within it. The challenge is how to recover a sense of criticality when all resistance seems to be futile.

Critique without action is not enough. The tools of design are used to inject an agenda within an industry that has marginalized this essential role of architects.

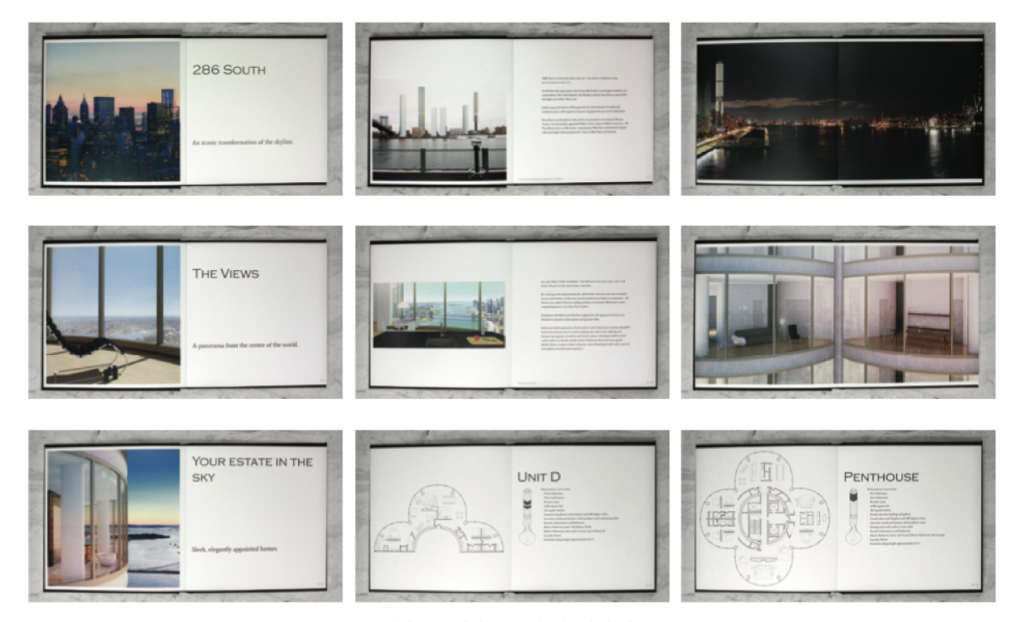

Select spreads from “286 South” sales book

Agenda

To sell real estate in this new typology, developers are directing their marketing psychology towards a distinct clientele predicated on the views. Owning a condo in the sky is owning that panoramic view of the city, and the materials created by marketing companies claim to offer the entire unobstructed panorama.

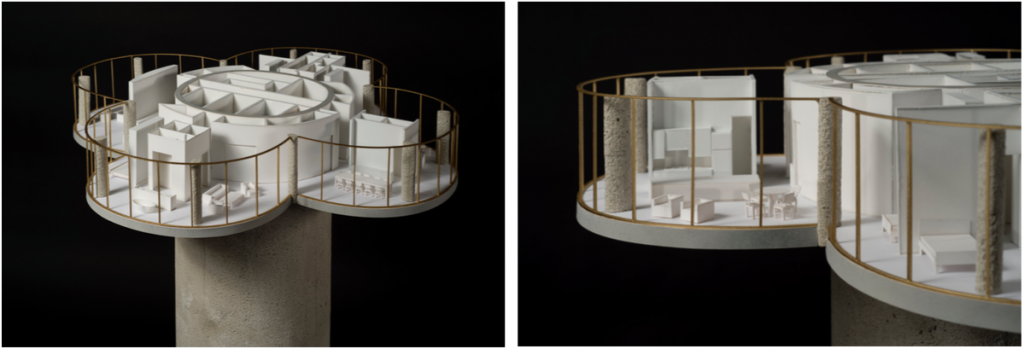

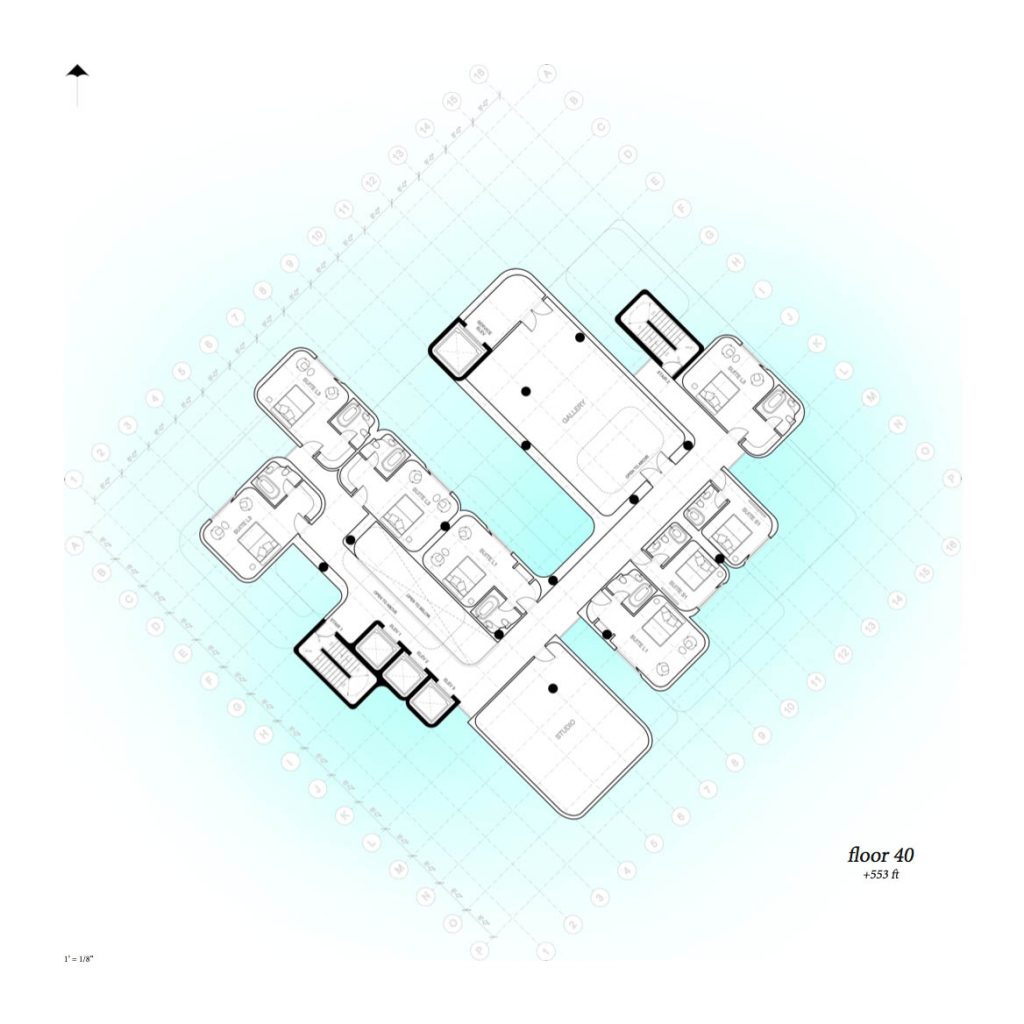

Through the design of “286 South,” a multi-family residential tower in lower Manhattan, this project explores the contemporary idea of panorama — split between an easily accessible, static view for sale and an embodied, dynamic form of vision. For the developer, I must glorify the uninterrupted widescreen view. But as an architect, I must redefine the panorama through embodied discovery. Thus I operate like a wolf in sheep’s clothing — it would seem I am designing for views, but my agenda is to design for vision.

Through the design of housing, it is the architect’s duty to elevate the living environment beyond the basic necessities of providing shelter. Working with the unique conditions and contexts afforded by this typology, the design has the potential to affect a more complete sensory experience for the inhabitant. By privileging an embodied practice of vision, this project forms a deep link between the way we see and the way we live. After all, seeing mediates the exchange between us and our surroundings. In these terms, “286 South” expands the possibilities within a contemporary housing type rarely afforded a critical eye.

WE ALL

Francisco Alarcon (MDes ’18), Rudy Weissenberg (MDes ’18), and Carla Ferrer Llorca (MDes ’17)

WE ALL is a public art installation in the Grove, a site at the intersection of North Harvard Street and Western Avenue that serves as an entry point from Cambridge into Allston. It presents a communal open space framed by a segmented, vibrantly colored wall, comprising hundreds of PVC and plexi-glass tubes that illuminate at night to create a lively and dynamic atmosphere. Amarillo-yellow ground paint and a series of benches activate the corner as a gathering space.

Kandor Architecture

“Architecture is always the exhibition of a myth,” as a certain critic put it in 1989, and the myth in this case is Kandor—the city that Superman kept shrunken in a jar. Preserved in ethereal suspense, Kandor was obsessively rendered by the sculptor Mike Kelley at the end of his life as colorful casts of glass, resin, plastic, and wax that represented the endless figurations of the mythical city in Kelley’s imagination. Our project relates Kelley’s “Kandors” to an earlier work, “The Educational Complex,” in which Kelley drew and modeled from memory the buildings of every school he had every attended. Just as Superman carried Kandor with him in a jar, so too did Kelley carry a city of educational buildings in his memory—his educational complex. The Kandor narrative was here applied to a specific project situated in Brooklyn: a campus for 2,250 kindergarten through high school students. The buildings were distinct, each representing a comprehensive school program with housing, playing fields, and auditorium, but combine to transform the city into the colorful exhibition of ‘Kandor Architecture.’”

This project was designed collectively by the studio: Esther Mira Bang, Andres Camacho, Chieh Chih Chiang, Feijiao Huo, Haram Hyunjin Kim, Hyojin Kwon, Kai Liao, Shao Lun Gary Lin, Meric Ozgen, Alexander Searle Porter, Noam Saragosti, Cheng Zeng

Third Semester Architecture Core: INTEGRATE

Selected projects from Third Semester Architecture Core

Bradley Silling (MArch I ’19)

Beining Chen (MArch I ’19)

Emily Ashby (MArch I ’19)

Khorshid Naderi-Azad (MArch I ’19)

Daniel Kwon (MArch I ’19)

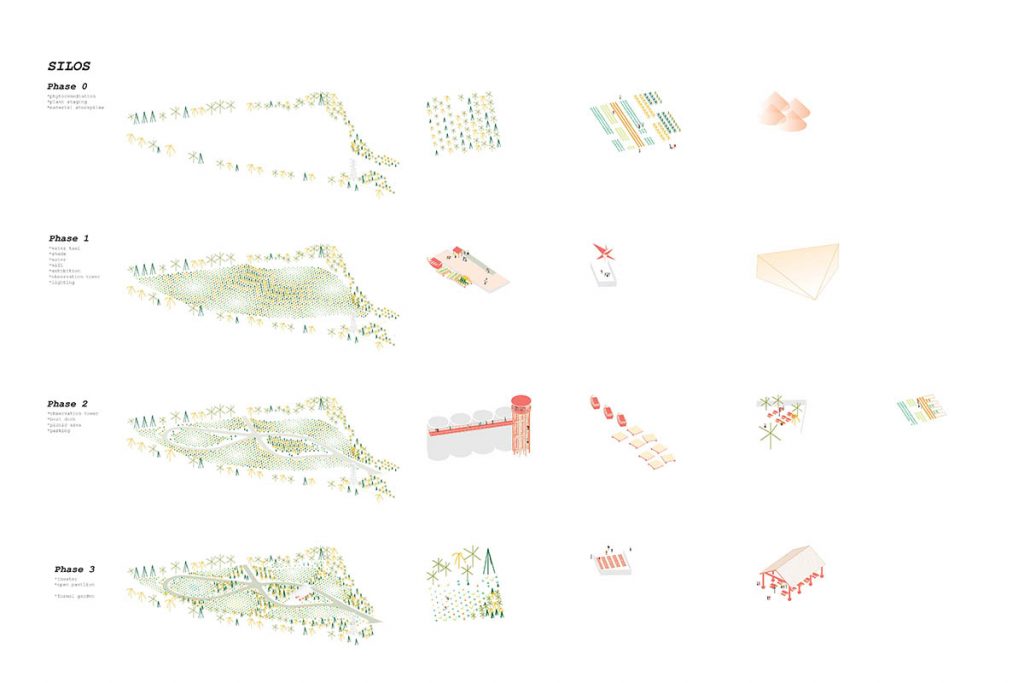

Landscape Architecture IV

Michelle Benoit, Daniel Berdichevsky, Meredith Chavez, Ana Garcia, Mengting Ge, Yanick Lay, Charlotte Leib, Mengfan Sha, Marisa Villarreal

Urban Villa (Contemporary Triple Decker)

Claire Djang (MArch I ’19), Alexandru Vilcu (MArch I ’19), and Andrew Bako (MArch I ’19)

Re-Tooling Metropolis: Provisional Landscapes, Emergent Urbanism in Houston’s Eastern Bayous

Yuxi Qin (MLA I ’17) and Christopher Reznich (MLA I ’17)

Catalog of Parts

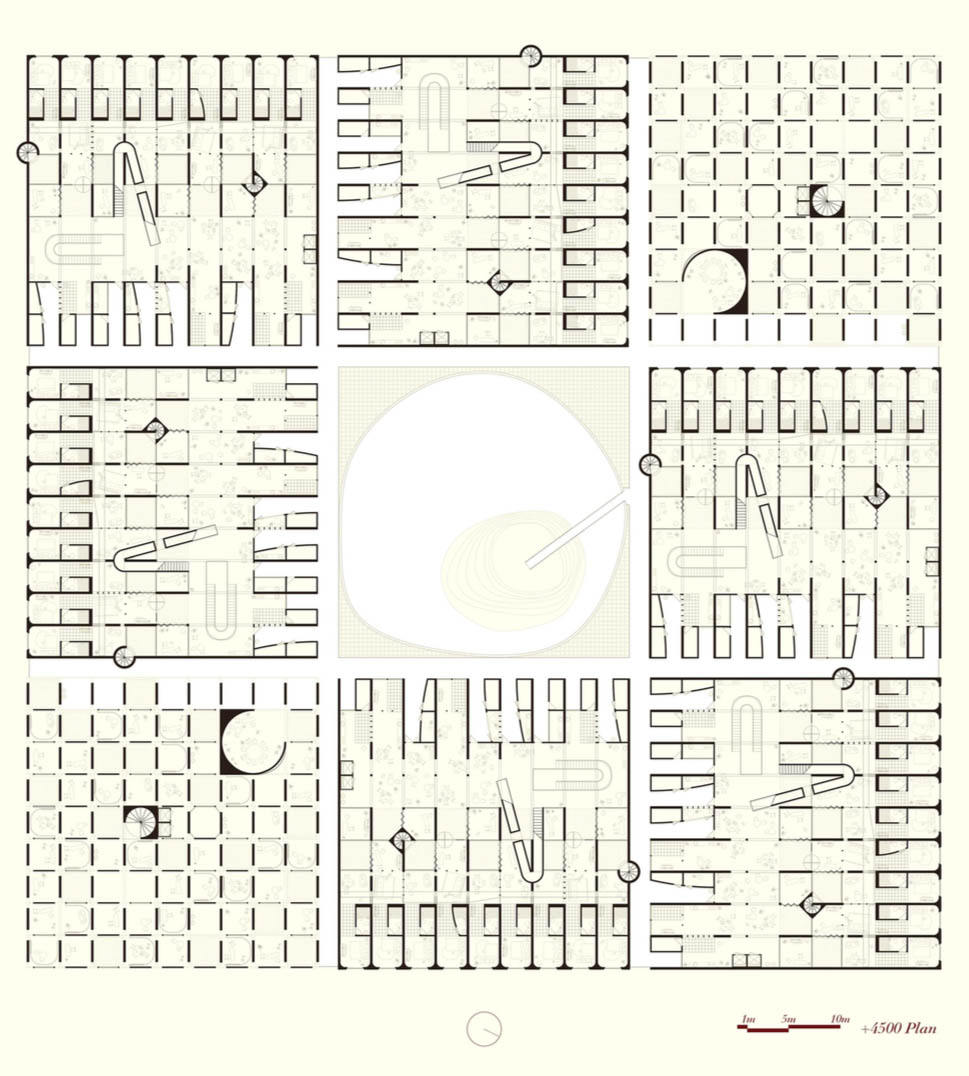

Yuyanguang Mou (MArch I ’17)

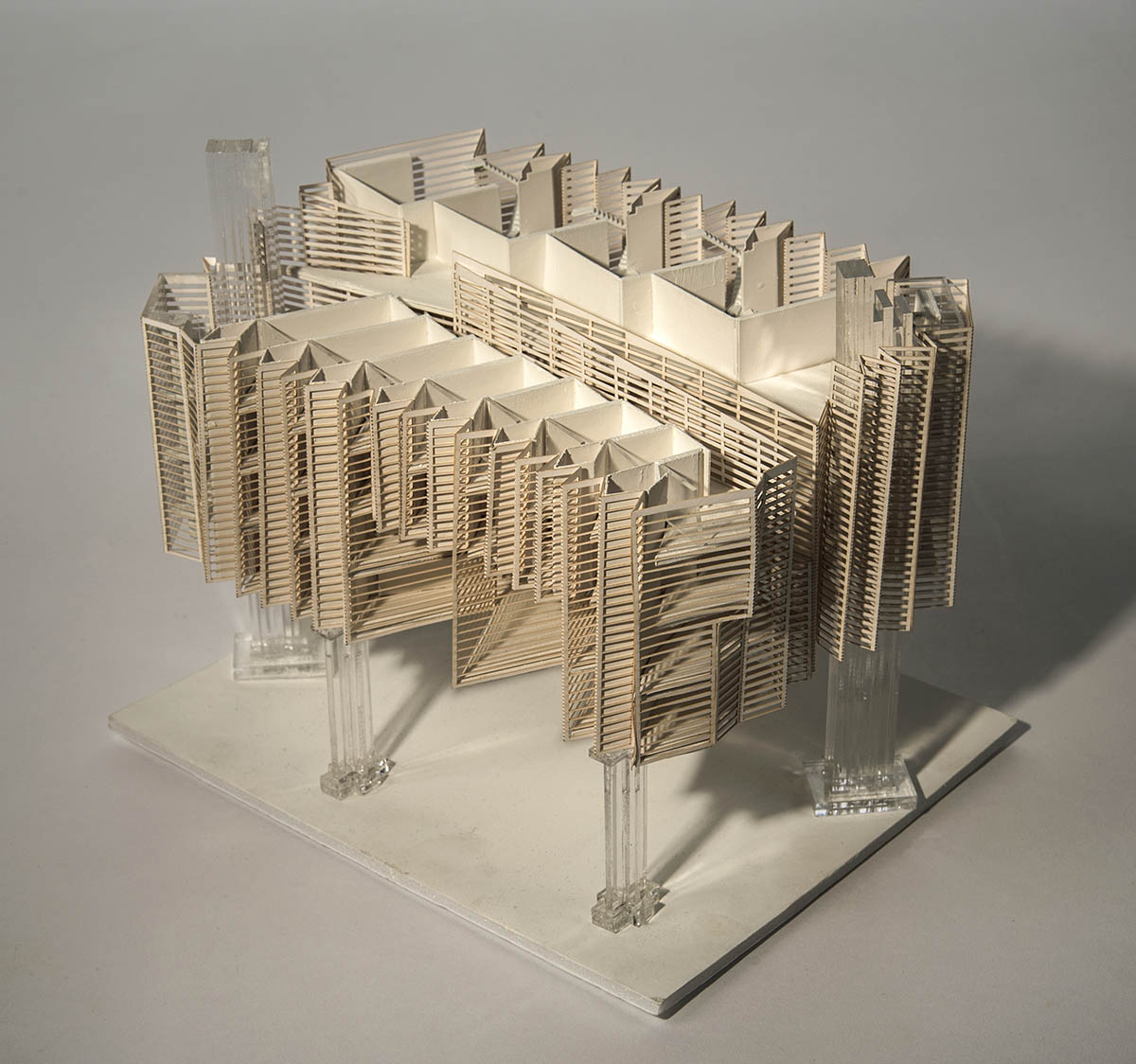

The ambiguity of tropical cities sometimes could be reflected through the flexibilities of its community structure and social relationships. The aim of the design as a housing block in the city center of Medellin, Columbia is to create a “catalog of parts”, a framework that could insert a new order into the community that offer both order and flexibility.

The design was composed by 3 squared elements: housing block, SOHO office, and community courtyard, representing the essentials of life components. The blocks were elevated, leaving the ground level only columns with differentiated shapes and orientations as a framework that offers opportunities for spontaneous organizations of outdoor social and commercial activities within this tropical context, as well as a more modest way of introducing a new order into the city.

Within the housing block, each unit was framed within a linear space of multiple programs, while the other linear orientation would then be composed of the same program of different units. The 2 orthodox orders offered the opportunity for the space in the housing units to operate in both directions, achieving both the individual procession of life behaviors as well as possibilities of shared communal spaces. The occasional disruption of the rigid grid such as the elevator, the trees, the stairs and slides leading up to the roof also reinforce the idea of cross-operating space.

The office space also bears the same thought as the walls in different directions have different width that indicate a dominant order and a penetrating one in the space. The joints of walls are cut open, offering a free-circulating space that could be organized according to the will of the user. Multiple spatial devices such as curtains and sliding doors are also play an important role in this flexible system.

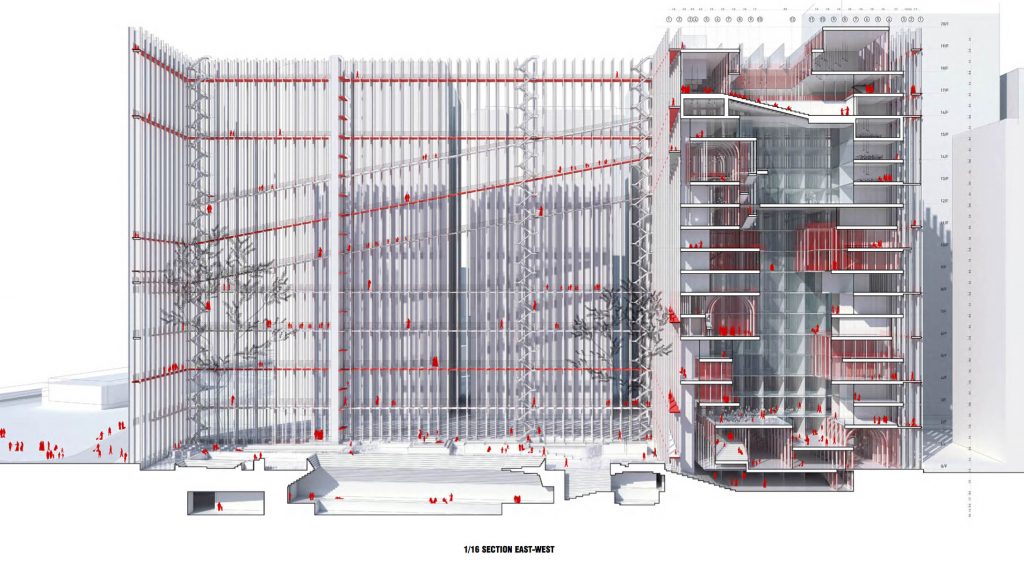

“Moving Things Around: Exploring Rossi’s Scientific Theater”

Jianwei Shi (MArch I ’17)

Heterogeneous Culture and Heterogeneous Archetypes of Public Buildings and Spaces

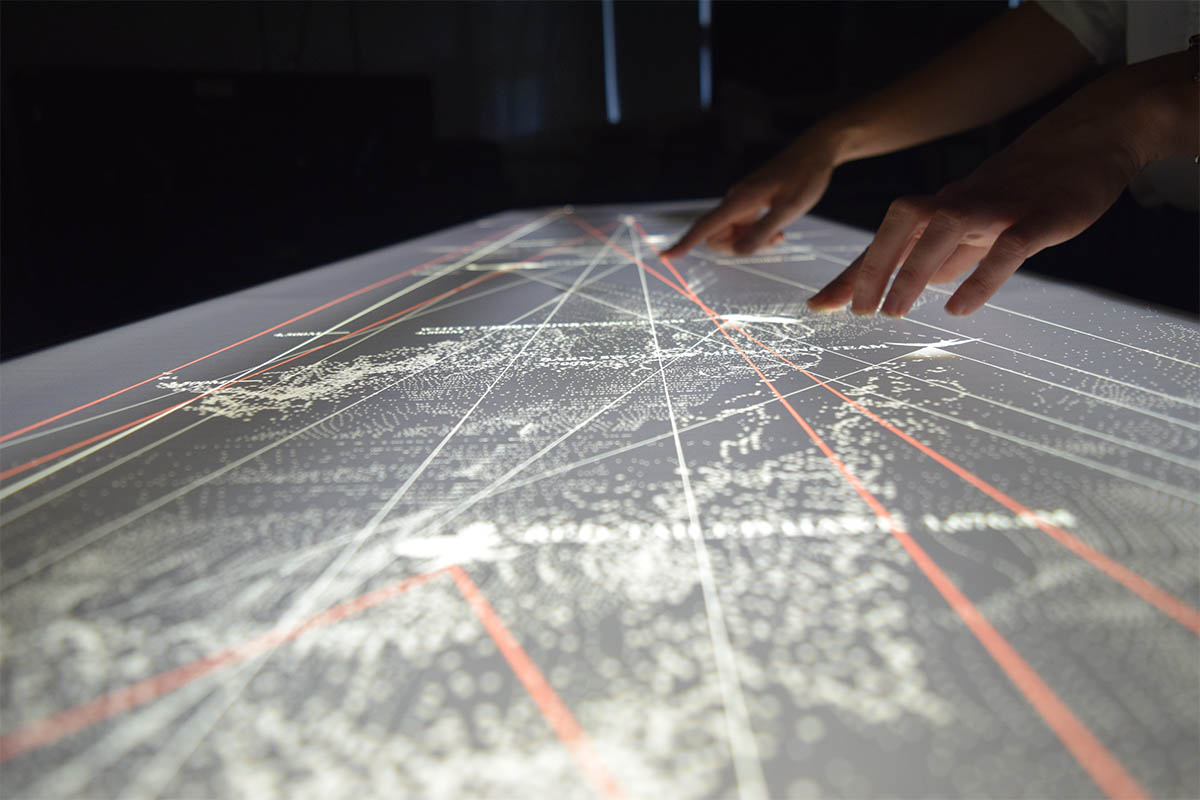

Mexico City is a city with very diverse culture and history. Different architecture and physical space from different period of history were still preserved on this land. The very ancient one is Aztec culture, the pyramid is one of its classic memorable archetypes. For the Hispanic culture that conquered the Aztec people, it laid a solid foundation for the form of historical center of Mexico city – Grid structure + Courtyard residential + Public Plaza with church; During Porfirian Era, the government leads the fusion of Amerindian, Hispanic and French Culture through improving urban environment by learning from Paris. The 20th century has witnessed a fast urban expansion and modernization. A lot of modern towers, public infrastructure and high-rise residential neighborhood took place during this period of time. The map shows heterogeneous archetypes of historical and modern buildings that are born out of the heterogenous culture.

Reference: Analysis on Archetypes and Elements of Alameda Central Park

For a building that is going to be located at the crossroad of these different urban environment and try to reflect upon these different culture physically, it will be very interesting to first look at how these different archetypes of buildings and spaces shape the public realm. Here, the Alameda central park area just beside the site is chosen as the reference. The Alameda central park is the largest park in the historical center of Mexico city. From the analysis on the archetypes and elements of park area, we can see how these diverse elements work together to provide a variable and energetic public space. Trees and canopy providing shade, linear promenade providing sightseeing route connecting different public programs, smaller plazas for outdoor exhibition, churches for religious event, courtyard for shops, cafe, museums. All these different elements and archetypes not only internally provide variable spaces, but also externally collaborate together to shape a convivial urban area.

Archetypes Internally Designed for the Cultural Programs and Externally Hybridized for the Plaza Zarco

Learning from the previous analysis, when zoomed in at the Zarco plaza, the main idea is also try to use different archetypes and elements to internally provide spaces for different programs and externally interact with surrounding environment to shape the plaza. The internal organization is using the dome as a heart of building that function as the spacious lobby and temporary venues. All the other archetypes of objects are respectively connected to the lobby forming different openings in the dome shell. Different archetypes provides spaces of very distinct quality. It makes you feel like, from the lobby, the heart of the buildingJianwei Shi (MArch I ’17), you can enter diverse and different worlds. Externally, different objects are hybridized with other archetypes to interact with surrounding environment. Dome distorted into a cone that form the entrance of the building and communicates with the church San Hipolito. The box turns into stairs with lattice cover to allow people sit and rest and see the plaza, etc. The building somehow is orchestration of multiple elements.

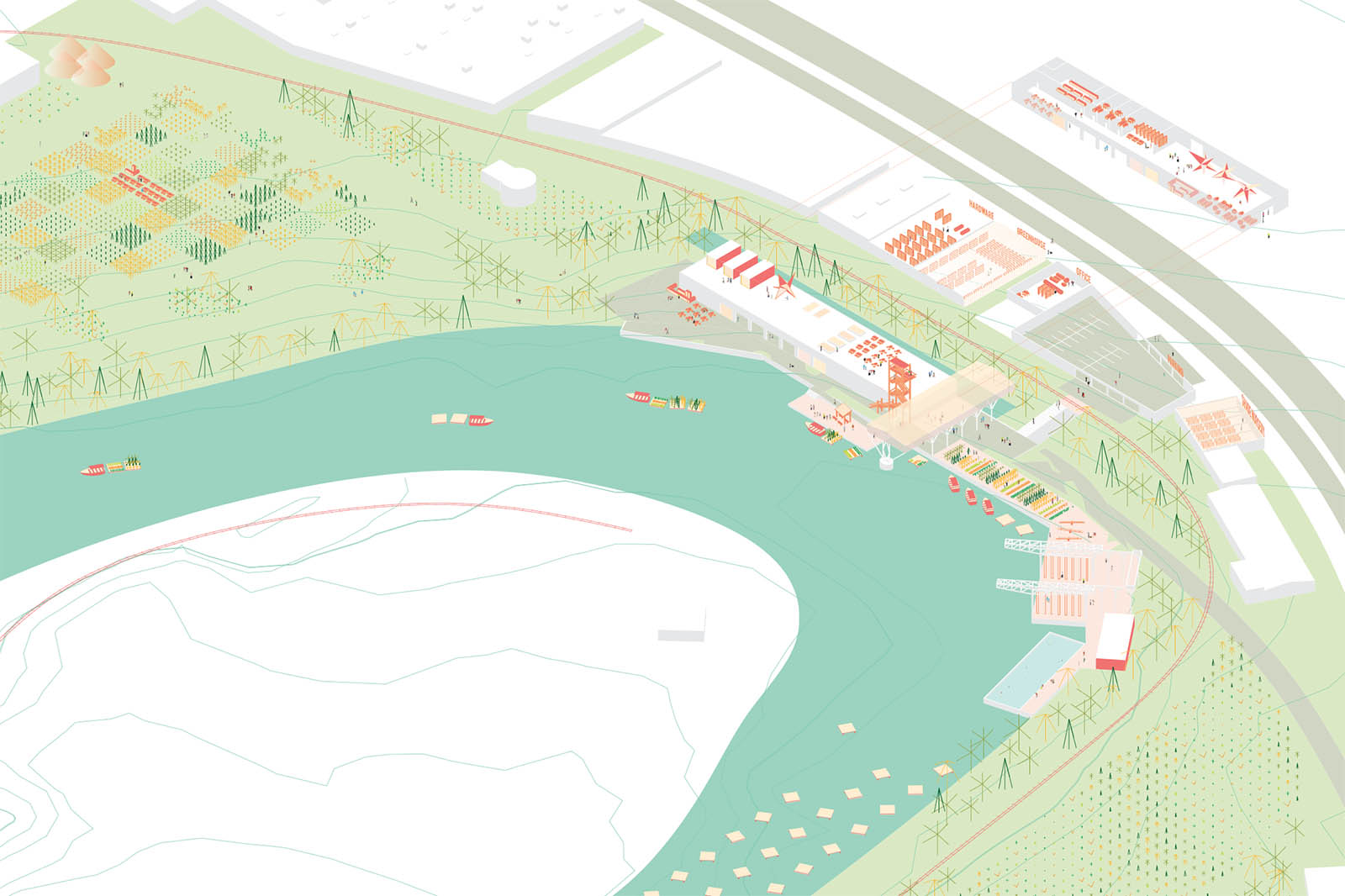

The Possibility of an Island

Andres Camacho (MArch I ’19)

Who would build the island? Would it be the Mitsubishi Group? The company who was complicit in the exploitation of labor, land, and extraction of coal in Hashima Island in 1890? Who would then leave abandoned and forgotten its workers and land, once coal proved to be obsolete? Would they seek a new image? Hashima Island could turn into Mitsubishi’s testing ground for reinvention of the obsolete; inverting the relationship between architecture of extraction to one of production, giving life to the forgotten and unwanted.