Representing Mimi Sheller’s “Aluminum Dreams”

Erin Ota (MDes/MArch I ’17)

Animation representing Aluminum Dreams: The Making of Light Modernity by Mimi Sheller.

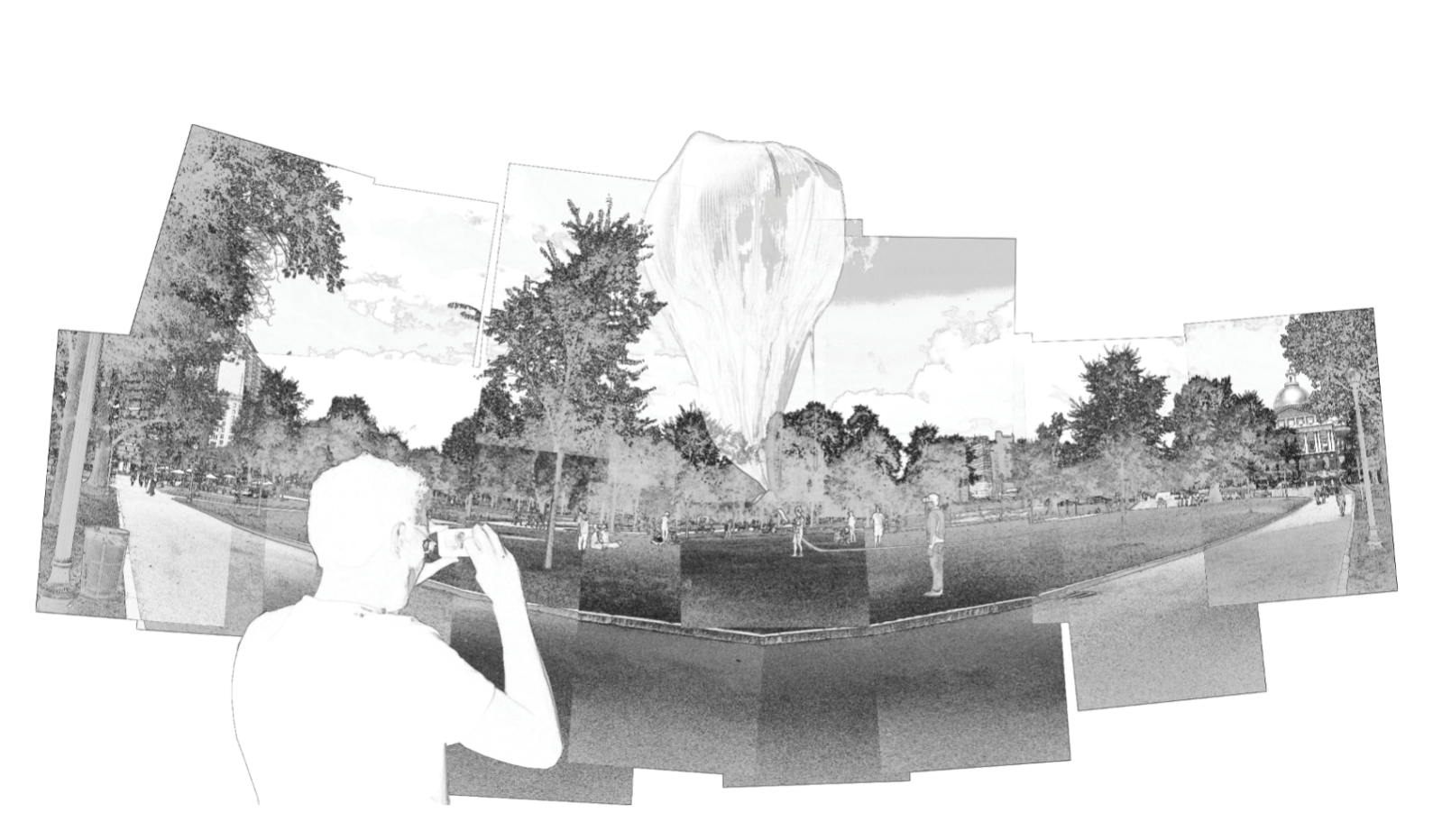

Autoscopic Extremis

Keith Hartwig (MDes ’18)

Autoscopic Extremis examines the aerostat’s many manifestations and symbolic meanings throughout history. In military and authoritative contexts the aerostat elevates the observer above the subject being observed below, essentially establishing a subject-object hierarchy in which the space of the ground below can be targeted and analyzed.

In civilian and recreational contexts the aerostat has enabled great feats, lifting people to incredible vantage points from which to view the sublime and majestic landscape. The genealogy of the aerostat suggests that its military and civilian histories are inextricably bound and are codependent on one another. In the same historical accounts of the aerostat we find it documented as a symbol of hierarchy and order as well as a symbol of freedom and egalitarianism. In the same historic episodes we see it being used to conduct military reconnaissance and to celebrate the abolition of tyranny. Or, as we are witnessing today, the aerostat is concurrently being used by the military to conduct domestic surveillance and by private companies to provide free internet to the developing world. It is in this contested and fertile space between the militarized and the civilian, the public and the private, the object and subject that Autoscopic Extremis resides.

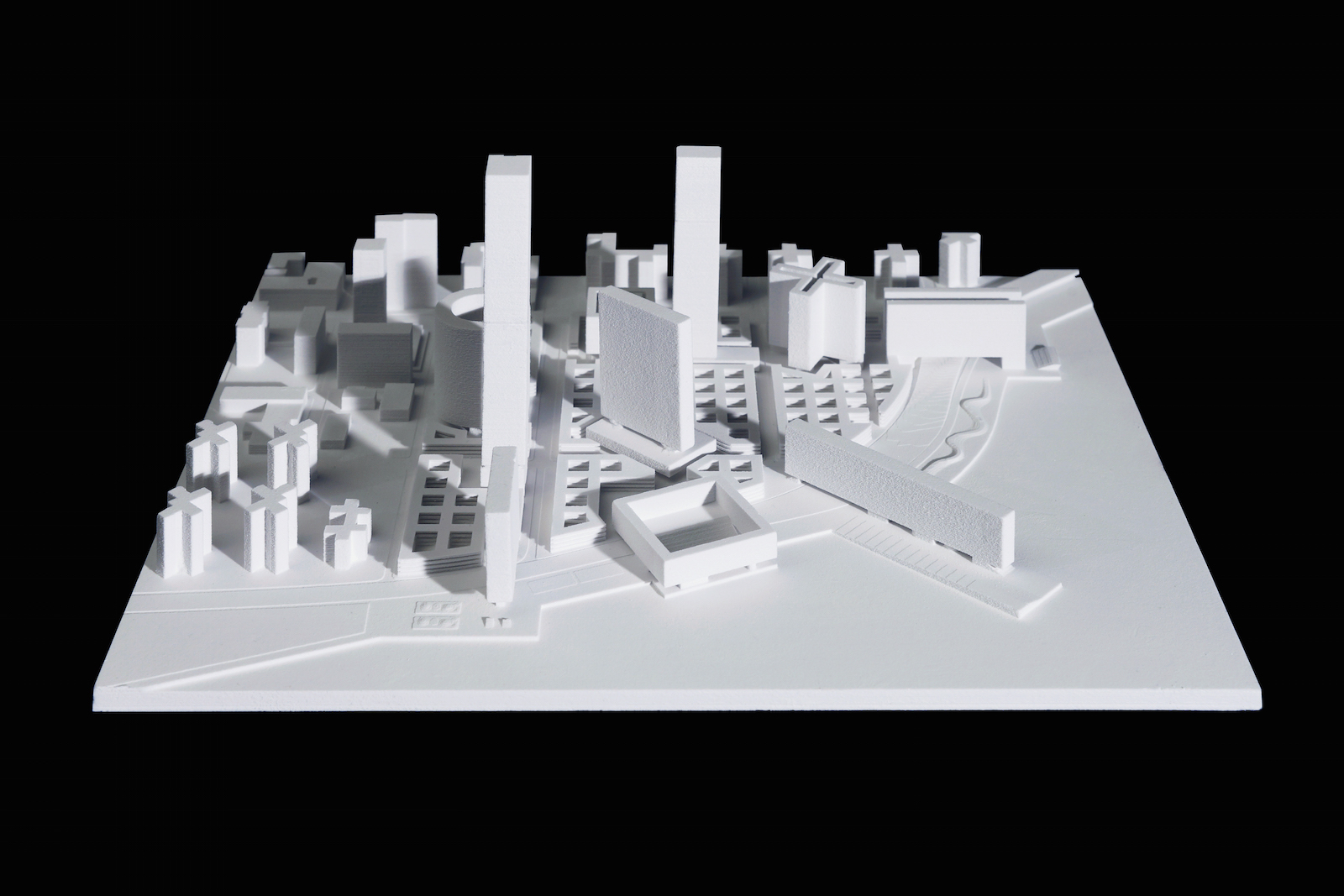

OBJECTHOOD

Liang Wang (MAUD ’17) and Lu Zhang (MAUD ’17)

The contrast between particular and universal, between individual and collective, emerges from the city and form its construction, its architecture. This contrast is one of the principal viewpoints from which the city will be studied. It manifests itself in different ways: in the relationship between the public and private sphere, between public and private buildings,between the rational design of urban architecture and the values of locus or place.

— Aldo Rossi

This project explores a new urban housing model that hybridizes the collective urban grid and the individual urban objects, from which the domesticity and life styles emerge to inform new urban ramifications at different scales. The urban objects here could be deciphered at two scales: one as urban fragments that mediate spatial and programmatic relationships with the city, one being the aggregation as a whole constructed at a larger scale, in which way we call it objecthood.

The project starts with the observation of contemporary New York housing fabrics, where exists a clear division between typical Manhattan grid and the Towers in Park typology. These two dominant types form the urbanism across Manhattan and beyond, each presenting unique spatial organization and life style embedded within. Based on this observation, the design proposal examines a hypothesis of combining those two urbanism: the normal grid and the abnormal objects, as a basic urban housing model to construct the city. Therefore, instead of using the existing Manhattan grid structure, a new grid module extracted from the basic Manhattan plot of 25ft is introduced to reconfigure – the courtyard system with generic dimension of 50ft by 50ft. It is the generic urban container of housing and infrastructure, which at the same time responds to the specific site constraints of FDR and the urban edge. The second system of series of objects introduced into the site holds public amenities and various housing types. The place where grid reconciles with the objects gives the public amenities shape and generates another layer of public space, being the recreational programs connected by a loop and landscape that ties the project to the city at a larger scale.

The emergence of universal urban grid and particular urban objects not only addresses the concern of urban multiplicity, more significantly, it informs a new urban housing typology at both programmatic and social levels. The spatial arrangements makes possible the coexistence of diverse living styles for multi-families, and its programmatic amenities embody the vision of a new social order which emerges as framework of the living community.

As a vision, this project is conceived at the scale of both a super block and a single bock, and the strength of the project resides in the duality to accommodate a variety of the scales and life styles from superblock to block and from city to buildings. As an urban experiment, this project serves as both an urbanistic housing strategy and a social framework. It could be re-adapted into different urban contexts with various parameters accordingly, thus to respond to the dynamics of our city today at large.

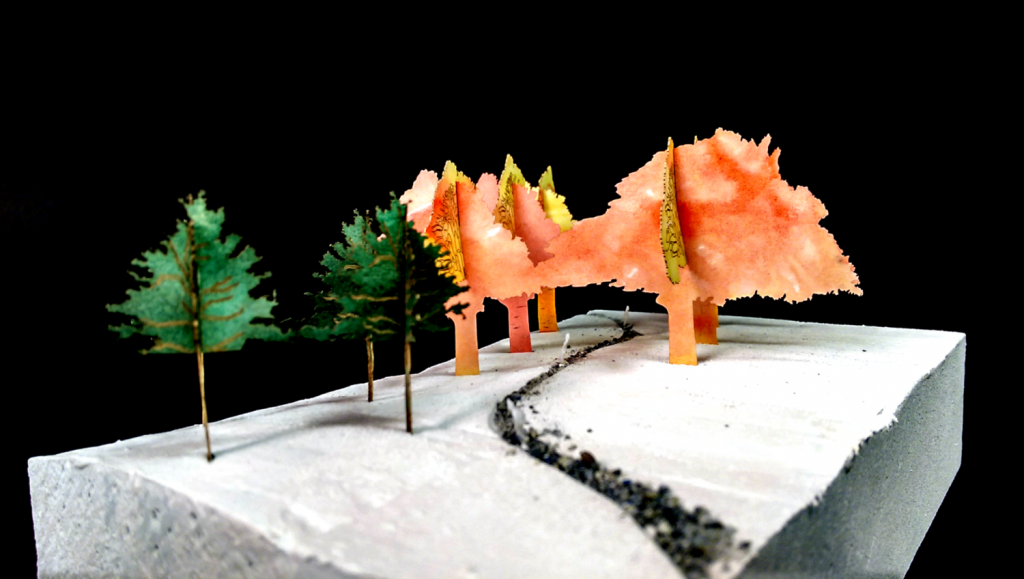

Wildland-Urban Interfaces: Attitudes and Altitudes

Oliver Curtis (MDes ’17)

This project explores the wildland-urban interface, “wilderburbs,” the growing borderland between forested wilderness and human settlement.1 These areas are increasingly subject to intense and destructive wildfires because settlement has encroached into the dry fuel-laden forests. I propose a three-pronged research approach to explore this issue: interviewing engineering experts at the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) Research Center, documenting the landscape of recent wildfires in the lower Colorado Plateau, and mapping the available construction material supply chain. The purpose of the data collection is to advance materially feasible and insurance-accepted landscape and construction methods to improve wildfire resistance in those prone areas of the American West. The field research will culminate in the production of a eponymously titled handbook with ideas to go beyond the proverbial defensible space and roofing material advice. The field research will be juxtaposed with photographic evidence of the fire’s restorative role in a fire-dependent landscape.1

1 Bramwell, Lincoln. Wilderburbs: Communities on Nature’s Edge. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014.

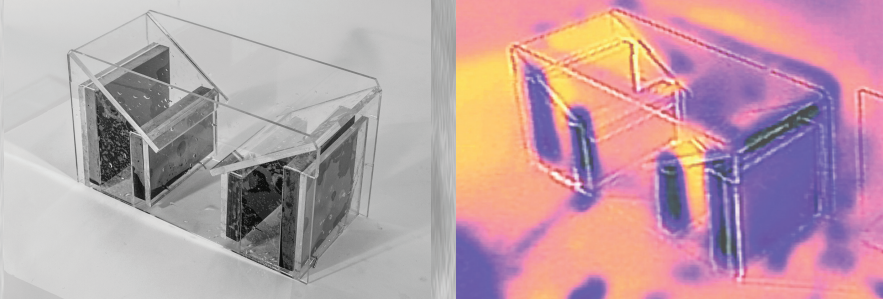

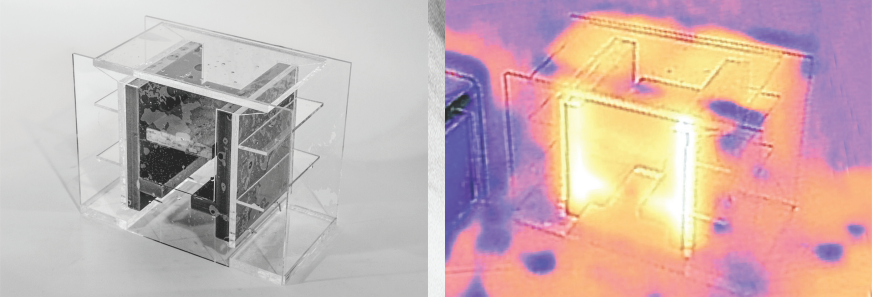

Hyperbolic Cosines: Recasting Form Finding to Induce Ventilation Performance

We explored the allometric potential of a funicular catenary form to both modulate interior climatic conditions and provide fresh air. The project was situated in the dry desert climate of Palm Spring, California because of the large year-round dry bulb daily temperature oscillations. Weather data confirmed typical daily diurnal swings of between 14-18° C, with larger swings in during the summer months (shown below). We anticipated that the form when in sync with its “peak” resonance cycle would produce conditions at the upward bounds of the Thermal Comfort Tool, developed by the Center for the Built Environment at the University of California Berkeley. While we were correct that large daily oscillations would result in a modulation of interior conditions, the effect of “peak” oscillation produced a reduction of approximately 5° C with ventilation rates exceeding the 10 liters/second per person. This was considerable drop through mass coupled ventilation.

The investigation of the Hyperbolic Cosines, an exercise in form finding through performative criteria uncovered a duality in tension. The tension uncovered exists between the forms ability to drop the overall temperature of the defined interior space and the ability to create air flow; air flow defined by pulling in exterior air into the interior and subsequent exhaust of to the exterior environment. The choking of airflow compromises the air changes required for the interior environment and inhabitants, creating a space resembling something closer to a hermitically sealed envelope. This is in opposition to an open exchange between the interior and the exterior, which was extracted from the taxonomy created through a framework of performative criteria. However, when the space is allowed to produce air exchange or air flow the ability of the form to drop the interior temperature diminishes. The exposure of the duality specific to an architectural intervention comes from the need to lower the interior temperature and the ability of the form to produce air flow. The inability of the form to function as inhabitable space limits the opportunities for an engagement at the scale of an architectural intervention, as shelter. When the form can not play host to inhabitants in the form of shelter the performative criteria must be questioned. The performance shifts from creating an interior space with the intent to produce comfort for human inhabitants to a mechanical provocation. The forms ability to drive mass air flow defines the intentionality closer to that of a mechanical intervention.

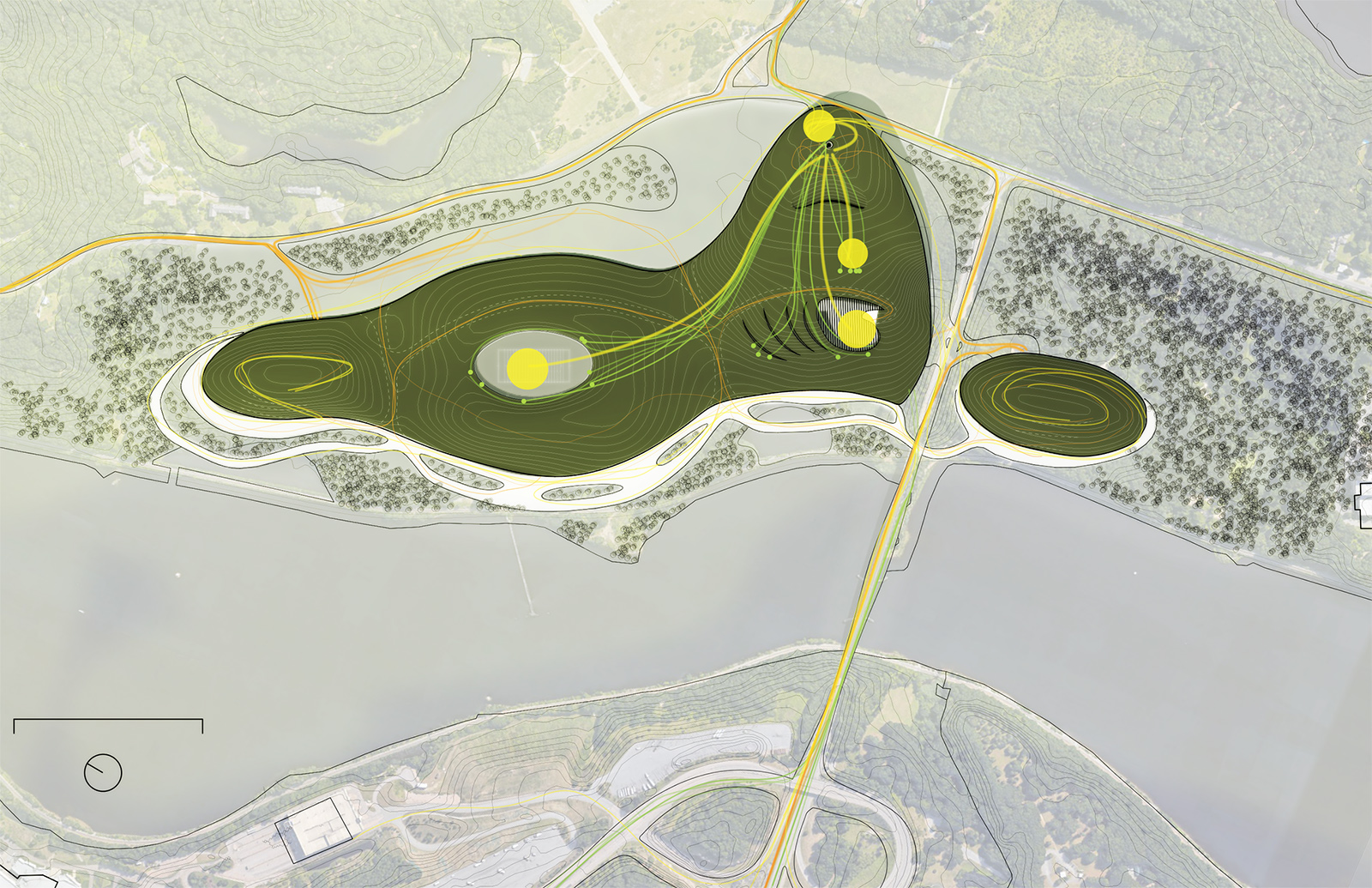

Show/Flow

Andrew Keating (MArch I ’17) and Scott Smith (MArch I ’17)

This project hybridizes an assortment of large public program into an iconic, regional-scale entertainment, leisure, and transportation complex supported by and supporting a waste-to-energy facility. The program—a regional transit hub for buses and electric vehicles, a sports stadium, an amphitheater for music performance, and a riverwalk—grows from the relatively open, semi-rural site, which currently hosts the Southeastern Connecticut Regional Recovery facility. The plant sits on the riverfront between the two largest casinos in the United States—Foxwoods, several miles to the east, and Mohegan Sun just across the Thames River to the west. This intensity of entertainment space and lack of urban density near the site motivated a search for large-scale program that would capitalize on the draw of the casinos, bringing visitors (and their attendant waste) to the facility, rather than solely relying on trucking as a waste source. Waste travels from the stadium and other facilities to the bunker hall via a vacuum system, so on site collection does not require additional trucking.

The building gathers the stadium, amphitheater, waste-to-energy plant, transit hub, and two large parking structures under a sinuous shell, which at times rises hundreds of feet above the landscape while at others meeting the ground plane and allowing visitors to walk up onto it. The shell takes part of its form from the spatial requirements of the waste-to-energy process, which, while linear, can be reorganized so that the tallest elements (the bunker hall, incinerator, and stack) all collect to one end. This creates the dramatic slope of The Hub, the central lobe of the greater shell. The tipping hall sinks below ground, accessible via a spiraling ramp that brings tipping traffic down while sending electric vehicles up drop visitors at the sky lobby for music and cultural events in the amphitheater. The amphiteather is suspended directly above the waste processing equipment. Bus traffic proceeds below the western portion of the hub, where visitors ascend into the transit hall, and can proceed up a long, sculptural ramp up through the oculus overhead and out onto the riverwalk. The waste-to-energy facility provides electricity and heating for the activities on site, and also to surrounding communities.

The project proposes a new way of thinking about regional-scale buildings and entertainment facilities, one that uses waste generated on site as an energy source, minimizes the carbon impact of waste removal, and reduces the inevitable loss of energy in transport from power plants to the point of use. Further, the waste-to-energy process supports a new kind of regional transit, relying on small electric vehicles, which may soon be able to drive themselves across the southeastern Connecticut region. The project results from the complexity of processes, not just within the waste-to-energy system, but also inherent to the site–flows of people, capital, vehicles, culture–bringing them all together into a manifold event space of event and flux, performance and circulation: Show and Flow.

A Slight yet Reliable Breeze

Aaron Mendonca (MDes ’17), Sarah Kantrowitz (MArch I ’17), and Jerónimo van Schendel Erice (MArch I ’16)

Tuning thermal mass with daily temperature cycles to drive buoyancy ventilation, we propose a thermally resonant interior architecture that lightly conditions exterior space. Scaling from house to palace, an allometric balance between mass surface area, thermal exchange rate, interior volume and aperture all works together to drive a gentle breeze.

Courtyard Breeze by Day

While comfort is codified, experience may be characterized through sensation. Ventilation, inside of a building, is fresh air changes but at the boundary it is a breeze. Characteristic ventilation is a function of stack height and temperature differential. Generating a sensible breeze involves clustering apertures at two ends of a maximum stack. Sufficient air changes requires a morphology that wraps a large mass surface over a tight interior volume. At the same time, the morphology must funnel breeze into a spatial experience without losing it to the vastness of an exterior sink.The courtyard satisfies these requirements encouraging a resonating architecture that goes beyond the comfort consensus so as to afford experience. During the hot afternoon hours, the interior thermal mass leaks a cool gentle breeze into the courtyard.

Balcony Breeze By Night

Scaling up to a palace grants a greater stack and stronger characteristic ventilation. However, leveraging the full power of the stack imposes a spatial program that arranges, in series, along the ventilation stream. Walls as well as structural floors act as thermal mass allowing for a high rate of exchange within a narrow volume. Floors are punctured in a staggered manner, at the center and then the periphery, causing the ventilation stream to weave around them. During the day, a cool downdraft descends into the building’s porch, much like the courtyard turned inside out. At night, the thermal mass drives a warm updraft that blows into the highest balcony.

Root

Adria Boynton (MDes ’16)

The city of Miami Beach experiences frequent flooding events due to sea level rise, heavy rains, and porous limestone that allows water to bubble up from underground.

What if Miami Beach specified rhizomatous, salt-tolerant grasses as a form of urban adaptation? Encouraging pervious surfaces would increase water absorption rates despite tourism-related disturbances. And by taking cues from Everglades’ sawgrass, plant species with dependable root mass could help alleviate localized flooding.

Franklin Park, Urban Forest

Diana Jih (MLA I ’18)

Power and Place: Seattle

Arthur Leung (MDes ’17), Boya Guo (MDes ’17), Hao Ding (MDes ’17), Mina Kim (MUP ’17), Jacqueline Palavicino (MDes ’17)

This project explores the boom and bust cycle as well as expressions of power embedded in Seattle’s urban forms.