Dolvi Township Project

Andriani Wira Atmadja (MUP ’21) and Nadege Giraudet (MArch I ’21)

Dolvi Township Project aims to develop a sustainable residential prototype on a steep terrain next to the JSW Steel Plant in Mumbai Metropolitan Region of India. Initially prompted by JSW Realty to construct 800 rental apartment units exclusively for their steel plant’s employees, the project was expanded by the design team to offer an additional 800 for-sale residential units, retail, public amenities, and green infrastructure that benefit the local community and the region. The proposal offers a vision for development that focuses on integrating challenging programs in an existing topography. By tailoring the township’s footprint to the site’s contours, and using construction materials that are produced from recycling the JSW Steel Plant’s waste, the project seeks to minimize its carbon footprint and build a sustainable living model for the community.

The Block

Daniel Garcia (March II ’20), Kyle Ryan (MDes REBE ’21), and Peeraya Suphasidh (MArch II ’20)

The Block is a mixed-use, transit-oriented development proposal of a 10 acre shopping center in Allston, MA. Located at the new Boston Landing MBTA rail stop, this project envisions diverse spaces for living, working, and retail in the form of a new elevated urban square, forming the foundation for a 15-min city.

A vibrant streetscape lined with retail gradually elevates to create a secondary village-like urban fabric. Composed primarily of low-rise, programmatically diverse blocks, the public and semi-public spatial sequences create an exceptional experience for residents, office tenants, and neighbors alike. Separated by attractive planted stairways, courts, and passageways, The Block scaffolds together all the necessary ingredients for creating premium living environments suitable and adaptable to residents’ unique needs.

Through design, the project cultivates the support systems and social lives we seek, shaping our unique daily experience and helping to unlock the benefits of community living.

The Block operates within the constraints of traditional development investment expectations, while pushing the financial model further to create something meaningful for the community with greater public benefit.

Building a Scalable Business in Data Centers

Sarah Fayad (MLAUD ’20), Ian Grohsgal (MArch I ’21), and Dixi Wu (MDes/MArch I ’22)

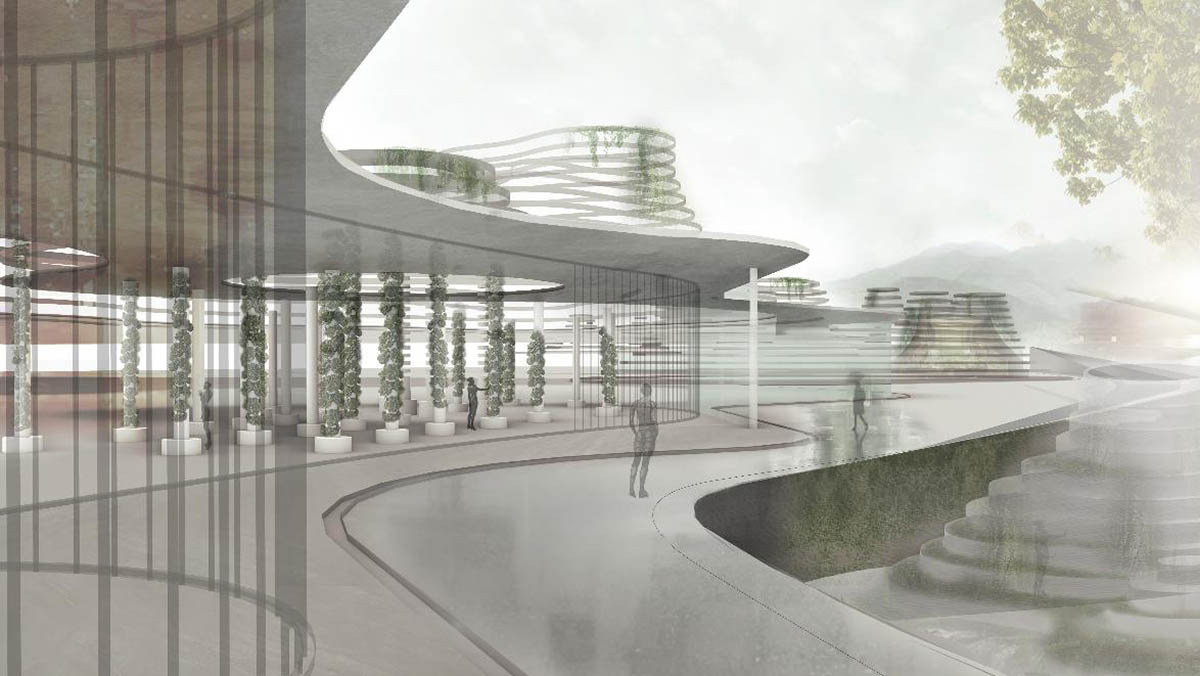

Data centers are typically a powered shed, located in remote areas, driven by profit, and primarily service enterprises. To set up a testing ground for a new scalable paradigm with a more human centered approach, Building a Scalable Business in Data Centers prepares for the 5G driven future while addressing the current growing demand in urban areas. Located along the Ottawa River in Gatineau to take advantage of the booming tech presence in Canada East, the data center sits at the nexus of benefiting three groups: the tenant, the community, and the investor.

The design serves the tenants by providing high-volume, low-latency data processing infrastructure and reducing their carrying costs. To achieve this, a holistic energy cycle integrates renewable energy sources from hydro Quebec and onsite solar panels to reduce the overall energy consumption, which is a significant portion of our clients’ carrying cost. On the other end of the energy cycle, the data center harvests the large amounts of waste heat emitted from the data facilities and channels it to the surrounding communities and public pool. For the community, the urban location allows for a digitally immersive, tourist destination via the extension of the municipal green belt, an interactive urban farm, and a heated outdoor pool using the data center’s excess heat.

In benefitting the tenant and the community, the investor can then receive returns from this digital backbone of local economic and community activity that services the current demand for data processing and prepares for the future market needs of 5G infrastructure and IOT.

Center – Periphery: Encoding New Processes in Shenzhen’s Boundaries

Ana Gabriela Loayza (MArch II ’21)

In 2005, Shenzhen’s Urban Growth Boundaries were created to limit urban expansion, protect water resources, and provide ecotourism routes. Center–Periphery explores the possibilities of an environmentally safe and sustainable textile industry to consolidate the Urban Growth Boundaries as innovation and production poles that connect urbanity and nature. This project has its foundations in the use of AI to imagine new landscapes of integration between a sustainable textile industry, rain-water usage, and the city’s inner nature.

The Textile Industrial Park is used as a subject to analyze and rearrange productive processes with available and emerging technologies. A new textile production can be achieved using organic crops, waste, and bio-fabricated materials integrated through state-of-the-art machinery. In combination with new harvesting, fiber processing, and spinning technologies, the traditional production sequence is transformed.

After analyzing the Urban Boundaries, potential areas of intervention are identified. Inspired by patterns of traditional agriculture, clustering and layering become programmatic and formal resources to replicate enclosed efficient industrial production spaces that progressively open into outdoor areas. This metaball-type pattern of organization is used to plan a new industry. The AI-based process generates suggestions to rearrange the land and manage resources through the manipulation and creation of imagery. While the images produced during the process are not meant to be interpreted literally, they help to translate the production process into landscape, forcing the following steps of architectural design into its formal and organizational considerations.

Exterior Experience

Interior Experience

Animated Spaces and Creature-Like Objects: Animistic Interactions With Smart Buildings + IOT Objects

Matthew Pugh (MArch II ’21)

At the GSD, I’ve been engrossed in a strange new world of objects with digital organs, of spaces animated in response to their occupants’ daily lives, and of empathetic interactions between humans and the objects they live with. My submission showcases design work emphasizing digital animism on two parallel tracks: one interested in animated interactions within architectural spaces—bringing them to life with kinematic actuation—and the other with anthropomorphized interactions with our IOT-laden objects.

The first section, “Animated Spaces,” demonstrates animistic interactions with the smart building through my thesis project, “Working in the Fun Palace: Archigrammatic Interactions With the Smart Building.” As opposed to the screen-based approach of many smart building designers, the project pulls from the playful, robotic design thinking of the 1960s to imagine kinematic interfaces for our increasingly ubiquitous smart building systems.

I developed three unique digital design techniques that animate traditional architectural representation tools: First, the project uses Bongo, an inverse kinematics plug-in for Rhino, to design robotic partition systems that allow spaces to reprogram with technocratic efficiency, in tune with the rhythms of their occupants’ day-to-day lives. Second, I used animation software to create narrative representations of the experience of living in such a roboticized interior. Finally, I designed a tool using Processing and Grasshopper to create a large dataset of suggested program-paired layouts, with the intent that this dataset could be used to train a ML model to react to occupants and repartition the space on its own accord.

The second section, “Creature-Like Objects,” showcases a similar form of digitized animism, but at the scale of the devices in our increasingly IOT-laden homes. The projects explore new forms of anthropomorphic interactions between occupant and a smart hub that starts to take on creature-like autonomy.

American Brick and the Difficult Whole

Yuming Feng (MArch II ’21)

Nothing engages more in the dialogue of “rationalism in material” than brick. On the one hand, the structural nature of brick was rendered meaningless by the modern need for large and flexible spaces; on the other hand, the critique of the new construction systems as cold and indifferent makes the cultural aspects of brick more important than ever.

As a multicultural center at Rice University, this project tries to establish a new ground for brick architecture in which brick fulfills both its structural value and cultural purpose. The facade is a brick architecture that inherits the material tradition of the campus; the interior, which makes use of timber, is an architecture with various scales of programs. The coexistence of the timber interior and the brick exterior immediately breaks the continuity between the content and context.

To address this discontinuity, the brick facade was designed to speak to the campus with order, symmetry, and proportion while responding to the interior with “material transfer,” which gives it the characters of timber. Moreover, the facade uses “diaphragm bonding” to perform structurally with timber. In this way, the brick not only “decorates the shed” but also participates actively in other fronts of the architecture. By reiterating the theme of material transfer, the four columns at the center are the architectural summary of the project. The details that distinguish the four columns focus on how they meet the ground and the roof, and clearly express the construction logics of the original and transferred materials.

Visit the 2021 Virtual Commencement Exhibition to see more from this and other prize-winning projects.

NuBlock

Erin Hunt (MDes Tech ’21) and Yaxuan Liu (MArch I ’21)

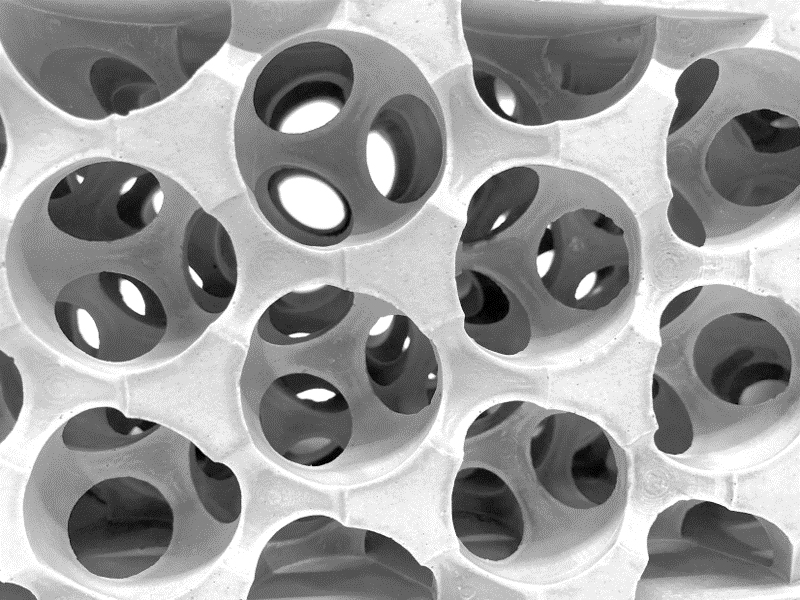

NuBlock brings a modern and aesthetic update to an architectural and structural elementary unit, the brick. With its innovative water-soluble formwork, this project can create lighter concrete bricks through a gradient of variable porosities with intricate geometries and infinite customizability. In areas where greater structural stiffness is required, the block is denser and vice versa. The goal is to minimize the quantity of material necessary through formal optimization while maintaining structural performance and decreasing the embodied carbon latent in concrete fabrication.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a biodegradable, water-soluble polymer that is conventionally used as a secondary support material in 3D printing. For this project, PVA is used as a primary print material for 3D printing concrete formwork. It allows for the creation of concrete components with hollow parts and undercuts, as well as other scenarios in which removing or breaking the formwork would be labor intensive, if not impossible. Typically, casting complex forms in concrete requires large and multipart formwork, but in this project a single PVA mold is used for casting and then dissolved with water, leaving the intricate block behind.

A new modular fabrication method was developed for NuBlock to overcome the limit of a 3D printer’s bed size, reduce the risk of print failure, and eliminate the material bridging and need for support structures. Multiple parts of a formwork are held together with wooden dowels. This allowed for the block’s volume to increase since the entire block was not being printed at once. An additional usable formwork was designed and printed in polylactic acid (PLA) filament to complement the PVA formwork.

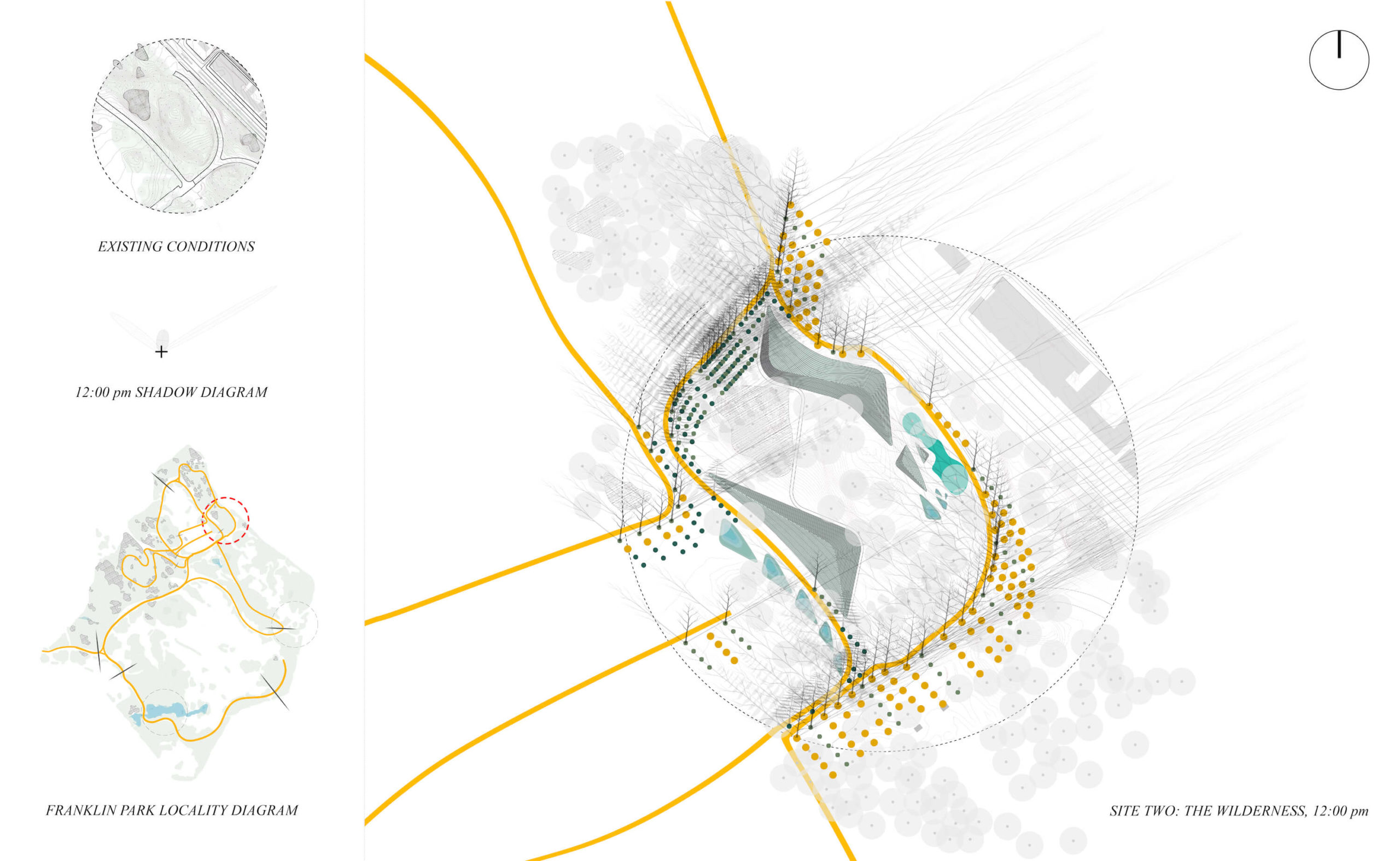

Running the Course: Unifying Franklin Park One Step at a Time

Lucy Humphreys (MLA ’22)

Franklin Park, the Eastern-most park of Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace, exists at the intersection of Roxbury, Dorchester, Forest Hills, and Jamaica Plain, four culturally and economically diverse neighborhoods. Although the 527-acre park provides significant recreative opportunities for nearby residents, it is not a unified park. For example, one cannot move comfortably from Refectory Hill to the Playstead without hitting a paywall or circumventing the golf course. Franklin Park therefore presents a tremendous opportunity for unification.

The experience of a large park can be a valuable one. Franklin Park offers an immersive interiority into nature that would otherwise be inaccessible for many residents surrounding the park. Franklin Park offers a common outdoor experience for neighboring residents, fostering a sense of community in the greater Boston area. Additionally, I believe there is value in revitalizing and investing in existing landscapes and communities. Elements like the cross-country course, the zoo, and the playgrounds offer key programming for the surrounding neighborhoods and Boston at large.

My goal in this project is to revitalize Franklin Park by augmenting the unique and world-renowned cross-country course that brings athletes from all over the world and unifies the park for a few days of the year. The path of the course is the catalyst for a new range and scale of social spaces, vegetation revitalizing strategies, and land forming interventions designed to stitch the park together. It will create a new rhythm for the park.

The aspiration of this project is to evoke further enthusiasm, excitement, and interest in Franklin Park as a community space for the surrounding neighborhoods and the greater Boston area. Race Day, and the landscape network it supports, renders the park truly public.

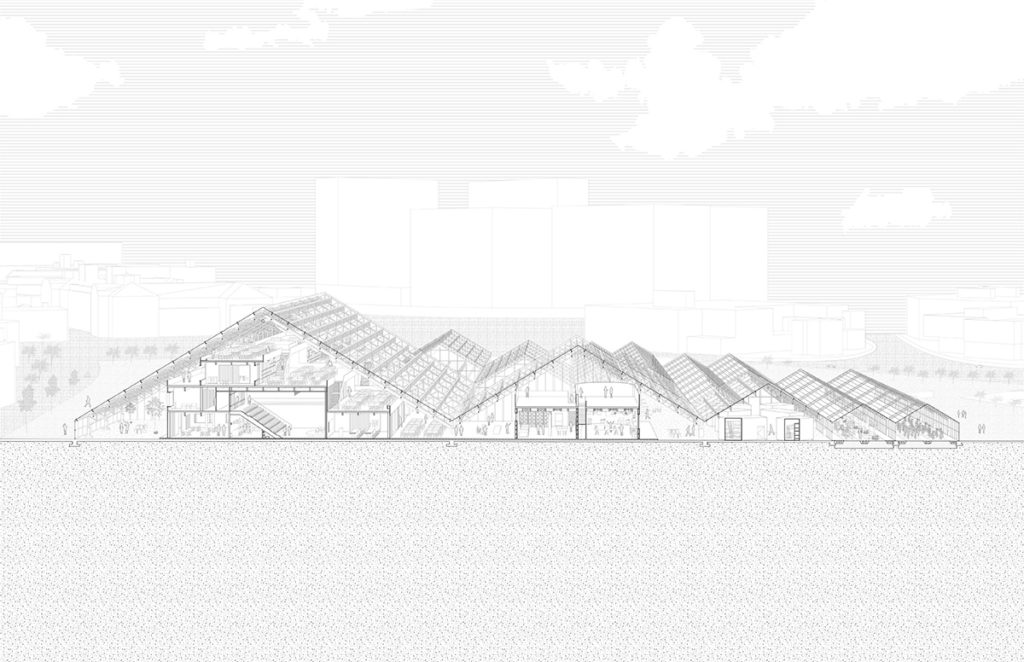

A School of Agritecture

Yijia Tracy Tang (MArch I ’22)

Deploying the typology of a greenhouse with operations of scaling and aggregation, this school complex manifests itself as a mediation between two distinct forms of knowledges: architecture and agriculture.

The project leverages opportunities created by an economic juxtaposition of two construction systems: lightweight steel trusses that prop up a huge continuously glazed roof with wooden volumes supported by post-and-lintel CLT structures underneath.

As the inner architectural artifacts rid themselves of burdens of waterproofing or thermal control under the protection of the big roof, a marvelous interplay between the two disciplines emerges through mischievous forms, materials, and interstitial spaces.

POV

Ali Sherif (MArch I ’23)

The sports complex splits the program into two types: collective and individual, spectated and personal. This manifests itself physically in two ways: the box and the worm. The boxes house spectated sports, basketball, handball, and roller hockey, and are designed as simple, inconspicuous sheds. Their white mesh exteriors and white-painted structure reduces them to their simplest of form and color. To minimize the building’s footprint, the boxes are sized to just the courts and pivot at a hinge point, creating public spaces on either side.

All other program and circulation cores exist in the worm. The worm is a bright red tube that sculpturally materializes, and stands out, amidst the brick fabric of Boston’s North End. The worm wraps itself around the boxes in one continuous motion, engulfing the white structures, breaking through the mesh barrier when it needs to accommodate for larger activities. It morphs itself into spectator seating, gyms, cafes, elevator shafts, stairs, yoga studios, among other things, preserving the appearance of thinness at all times.

While the boxes are dimensioned to the scale of the courts, the worm is dimensioned to the scale of the person. The thinness of the worm creates an intimate spatial experience, affording the individual a sense of ownership over the space being used at a certain moment in time. In addition, the sectional scalar disconnect between the box and the worm provides the user a typically non-existent layer of discretion while exercising. The individual is maintained at the position of the spectator at all times, while the collective is preserved as the spectacle.