Igniting Radical Imagination

“Think about someone who harmed you deeply. What would it take for you to sit down across from them, and ask them, Why? What supports would you need?”

This is one of the prompts that Deanna Van Buren, architect, activist, and director of Designing Justice + Designing Spaces (DJDS), asked the audience to consider during her talk, “Designing Abolition,” on Tuesday, March 4, at the Graduate School of Design (GSD).

After her presentation, Van Buren was joined in conversation by her collaborator Andrea James , an activist, lawyer, and community organizer whose goal is to end incarceration for women and girls.

Van Buren designs systems of care that replace the carceral system. Her organization’s buildings focus on community-building and restorative and transformative justice—spaces where people can have healing conversations to resolve conflict, get support finding jobs and childcare, grow and prepare healthy foods, and work with community members to support the neighborhood.

Diverting people out of the prison system and into systems of care requires collaborating across industries. For example, Van Buren worked with lawyers, prosecutors, asylees, and others in Syracuse, New York, supporting The Center for Justice Innovation to open the Near Westside Peacemaking Project , the country’s “first center for Native American peacemaking practices in a non-Native community.” Now, instead of sending people to prison, judges can send them here for support within the neighborhood. The center features a Women’s Reentry Lounge, Circle Event and Art Space, Youth Zone, and Welcome Lobby. People have come to congregate at the center, gardening together in the yard, and using it for quinceañeras and engagement parties. This, says Van Buren, moves people from “incarceration to community cohesion. Prisons don’t keep people safe; this keeps people safe.”

In California, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights launched Restore Oakland the nation’s first center for restorative justice and restorative economics, which prompted Van Buren to create the real estate side of DJDS to acquire properties in ways that best serve communities. DJDS also supported Allied Media Projects to develop the LOVE Building in Detroit, Michigan, a commercial space with offices for nonprofits, which inspired DJDS to pursue the Grand River at 14th Parcel Assembly, with additional facilities for family support, youth activities, food justice initiatives, workforce development programs, education and literacy training, health and wellness services, and arts and culture groups. DJDS also designed the Common Justice Headquarters in New York, which serves victims of violent felonies and diverts people from prisons, as well as mobile refuge rooms to house formerly incarcerated people, exhibited at the Smithsonian Design Triennial under the title “The Architecture of Re-Entry.”

Restorative justice, transformative justice, and trauma-informed design are at the foundation of Van Buren’s practice, which she developed in part during her 2013 Loeb Fellowship , after working as an architect for 12 years. At the GSD, she described how she thinks about designing a room where people can have difficult conversations—the core of restorative justice, whose premise is that harm can be resolved without punishment, and that with the right supports in place, people can thrive. “A core part of what it means to be human,” Van Buren explained, “is conflict and resolution. We avoid it. We don’t have skills. We don’t practice it.” Rather than sending someone to jail for attempted murder, for example, the two parties can sit in a room and talk to one another. Designing a space like this requires a deep understanding of trauma and how it works at the physiological level. “If you’re going to go into a conversation that’s very traumatizing…you need an environment that’s going to help you with that interaction.” She described how limited views, access to daylight, art that reflects our identities, and the ability to move the chair away from the other person are just a few of the design elements that create felt safety, which calms the nervous system.

During her tenure as a Loeb Fellow, Van Buren created her own multidisciplinary course of study to develop skills she knew she’d need. “I rode my bike over the snow in Cambridge to take classes at different schools across Harvard. I took Marshall Ganz’s public narratives class at the Kennedy School, and planning with Michael Hooper at the GSD. I took a class on research methods for designers at MIT.” She enrolled in a course on analyzing visual data at MIT, and a workshop at Lesley University on Circle Keeping, a restorative justice practice that brings into conversation people who were part of an incident that caused harm. Her process was intuitive and interdisciplinary, in pursuit of “mak[ing] space for restorative justice.”

Van Buren proposed that, as we face a complicated era that some call “the great turning,” shifting from profit-focused industry to supports for people and the environment, we have the opportunity to choose how we intervene. Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s definition of abolition provided a framework for her talk and the ensuing conversation with James, which focused in large part on how to close prisons in New England as a model for nationwide prison closures and alternative systems. “Abolition’s goal,” writes Gilmore, “is to change how we interact with each other and the planet by putting people before profits, welfare before warfare, and life over death.”

Van Buren suggested that we might consider three key questions: “What do we need to dismantle? What is the world we want to build? What skills will be required?” In the US, she said, “we have a lot to dismantle.” We’re facing “centuries of gross structural inequity in every community in this country and around the world,” which is evident in tree and food deserts, rural and tribal lands disinvestment, the US’ 1969 Freeway Act, and “co-located toxic land use,” among other challenges. Prisons in the US were built on “punishment, torture, and enslavement,” which “has to be unbuilt.” And, although people are attempting to open new prisons, more than 400 have been closed in the US in the last fifteen years, most of which now sit vacant.

“Designers are world-builders,” Van Buren said. “I cannot think of anything more important for designers to do,” she said, “than to ignite radical imagination.”

She described how the Atlanta City Detention Center, a jail that housed thousands of people, could be transformed into a Center for Equity, a food ecosystem, or community space, with potential for education and housing opportunities. The secure lobbies could be reinvented as “super lobbies where people can come in and be navigated to care-based resources.” We could “reimagine the justice core.” She illustrated this point with a map of the city’s justice system—the courthouse, police station, schools—and emphasized the importance of choosing an easily accessible site for the restorative justice center that is close to the justice core.

Instead of turning to punishments when people hurt one another, transformative justice views the harm as “a breach of relationship.” The people harmed need to “have their needs met” while the person who hurt them “makes amends.” No one, therefore, is being taken from their community, and returned to it later with the additional layers of trauma inflicted by prisons. Transformative justice helps people “heal by examining underlying issues, such as racism.”

New projects by DJDS include participation in a collaborative initiative to determine how to develop the newly closed MCI-Concord, which was the oldest operating prison in the nation, founded in 1878. Van Buren is also working with James to advocate closing women’s prisons in New England. Their focus is the last women’s prison in Massachusetts. With only 135 incarcerated women in Framingham, James argues that it would be relatively simple to close, and would mark the end of women’s prisons in the state, although the current governor is investing to construct a new women’s prison. Van Buren offers alternative models to prisons. Transformative justice spaces like the ones she created in California and Michigan divert people from prisons into systems of care, where they can find the support they need to remain in their communities.

“We have already created an exit plan for every single one of those women [in the Framingham prison]. We are uniquely poised in Massachusetts,” said James, “to close the women’s prison and create what different looks like, to become a model for the rest of the country.”

She and Van Buren continue to push to end incarceration for women and girls throughout the country, and to implement the abolitionism defined by Ruth Wilson Gilmore. In order to create new systems, Van Buren argues that we need to “develop the ability to hold complexity,” undertaking interdisciplinary collaborations to solve complex problems. To best prepare for the world that awaits them, Van Buren encouraged current GSD students to enroll in courses across Harvard’s schools in pursuit of their interests, noting that the MDes program provides a model for the kind of interdisciplinary study that helped her achieve her goals as a designer for transformative justice.

“A Radical Obvious Idea”: “Carceral Landscapes” Confronts the Role of Design in Mass Incarceration

A photograph from the 1950s depicts Chicago’s Cook County Jail in a fragile state. An imposing wall had crumbled, leaving bricks—many of which were produced by inmates themselves—scattered in the yard. Melanie Newport , Associate Professor of History at the University of Connecticut, shared the image as part of “Carceral Landscapes,” a symposium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in October that aimed to foreground the role of architects, designers, and planners in confronting mass incarceration in the United States. The photo of the jail in ruins served as an evocative touchstone for discussion throughout the event. Speakers and audience members alike reflected on the imposing facilities designed by architects to detain millions of people as well as the effort required to unmake that architecture.

Organized by GSD faculty members Lisa Haber-Thomson , Lecturer in Architecture, and Dana McKinney White, Assistant Professor of Urban Design, and co-sponsored by Harvard Law School’s Institute to End Mass Incarceration , the symposium focused on the physical infrastructure of incarceration, highlighting its histories and present conditions as a step toward dismantling an oppressive system. As Newport said, “the gradual escalation of mass incarceration happened brick-by-brick.” Bringing legal expertise and sociological studies together with research on the built environment, the symposium sparked an interdisciplinary conversation about a social problem with multilayered origins and impacts.

“We as designers are culpable in part for the issue of mass incarceration in America,” McKinney White explained in an interview, noting the active role that architects, including major firms, have played in building prisons and jails. “It’s critical that this conversation take place at the GSD because we are in a very influential position,” McKinney White continued, “not just as a school of architecture, landscape architecture, and planning and urban design, but also as a part of Harvard, where conversations about mass incarceration are happening at the Law School and at the Kennedy School of Public Policy. This is a moment of leaning into that conversation and actively talking about our role in it.”

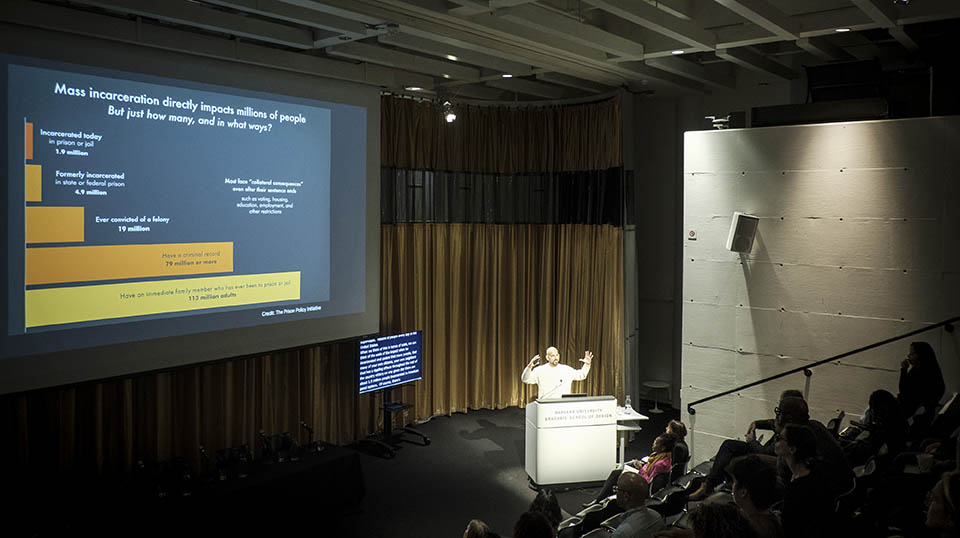

The scope and urgency of the problem became clear through a series of bracing charts shared by Andrew Manuel Crespo , Morris Wasserstein Public Interest Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and Executive Faculty Director of the Institute to End Mass Incarceration. With a per capita incarceration rate dwarfing that of other developed nations, the United States carceral system is an extreme outlier among peer countries. On any given day, nearly 2 million people are incarcerated in US facilities, and millions enter the system every year. Mass incarceration impacts an astonishing number of people: Crespo estimated that the half of Americans have been affected, either by entering the system themselves, living under supervision of a criminal justice system, or having an immediate family member who has. As a phenomenon, mass incarceration is both a widespread and hyper-focused, disproportionally impacting people of color and those living below the poverty line.

While the present justice system may seem intractable, buoyed by appeals to public safety, Crespo emphasized that mass incarceration is a recent phenomenon. Incarceration rates started to spike only in the 1970s and peaked in 2009. Over that time, confinement became a “backstop for problems we can tie to social conditions and social inequality.” He described the need to end mass incarceration as a “radical obvious idea,” one that would require a direct confrontation with deep social problems rather than a continued reliance on carceral “solutions.”

While lawyers and law enforcement officials animate the criminal justice system, architects had a crucial role in creating it. Haber-Thomson introduced the symposium with a critical history of the emergence of carceral architecture. She noted how studies by Michel Foucault and Robin Evans have shaped contemporary perspectives on how modern prison building typologies, including the notorious panopticon design, emerged in industrializing Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. Haber-Thomson argued, however, that such histories of prison must now be augmented by the recognition of longer continuities between mass incarceration and enslavement.

The full history of incarceration is a daunting account of oppression. But it also reveals moments of subversion and strategies of resistance that people in the present can recover. “Every history of these spaces contains contestation,” Newport said. Her study of the Cook County Jail, the largest single-site jail in the country, shows that the facility is far from monolithic and stable. Instead, it contains heterogenous architecture and variable land use patterns that reflect evolving ideas about the role of the jail in society. At times, Newport detailed, “jailed people maintained a degree of public visibility,” with information flowing in and out of the structures. Though increasingly isolated today, Newport emphasized the importance of moments of “porousness,” which exist in living memory, as productive counterpoints to the present.

Some particularly dysfunctional jail facilities in urban centers have attracted national attention, notably Riker’s Island in New York and Men’s Central Jail in Los Angeles. While acknowledging the struggles at these sites, Sarah Lopez , Associate Professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the Stuart Weitzman School of Design, drew attention to the rapid expansion of migrant detention facilities in Texas, which have received relatively little public scrutiny. For those constructing this carceral infrastructure aimed at migrants, “remoteness and invisibility is like a science,” Lopez said. Difficult for journalists and activists to access, these facilities are also embedded in rural communities with few other economic prospects. The promise of revitalizing rural areas is one selling point for the prison industry, though Lopez noted that the anticipated benefits rarely materialize, with profits extracted by major companies. Still, the dependency of rural political districts on the detention economy helps perpetuate the system overall.

How can designers hope to make a difference in these conditions? Crespo noted that the infrastructure built during the prison boom of the 1980s is now aging, with some facilities reaching the ends of their anticipated lifecycles. According to Crespo, architects may have an opportunity to force a change by withholding their expertise, essentially letting the walls of jails crumble, like those in Newport’s photograph. In this environment, disputes about “vocational ethics” will surely arise within the field. Crespo mentioned a pressing example: Should designers help make jails and prisons more humane, for example by bringing the facilities into compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act? Or should the sole focus be on arguing against the incarceration of disabled people in the first place?

The time for pondering such ethical quandaries may be running out, Lopez suggested. She pointed to the rapid pace with which carceral facilities can be constructed in Texas, with sites for more than a thousand detainees erected in as little as a year. She sees a “dystopian future” of scaled-up, dehumanized imprisonment already coming into existence while the architecture profession lags behind. Only in the past few years, Lopez noted, did the American Institute for Architects ban designing for execution facilities and solitary confinement.

As McKinney White said, however, “until we see more development in solution-building, we’re going to have to try out lots of different approaches, innovate, and be willing to go out on a limb with ideas that may not always be favorable.” Such innovations are the subject of respective courses at the GSD that she and Haber-Thomson will lead to foster further discussion among GSD students. The symposium included a workshop for students focused on the writings of imprisoned people and their experiences with architecture, a project that Rachel Fischer, a first-year MUP student, discussed during a brief presentation.

The symposium was a call for designers to stay engaged in finding alternatives to mass incarceration. Far from an abstract problem, the system comprises concrete spaces that are inhabited by people and situated in communities, and that have transformative effects on the land. Still, just as architects and designers played a role in building this infrastructure, the symposium suggested that they can be unbuilt just as readily. As Crespo said, invoking the crumbling walls of Cook County Jail, “things that seem inevitable feel that way until the moment when they aren’t.”