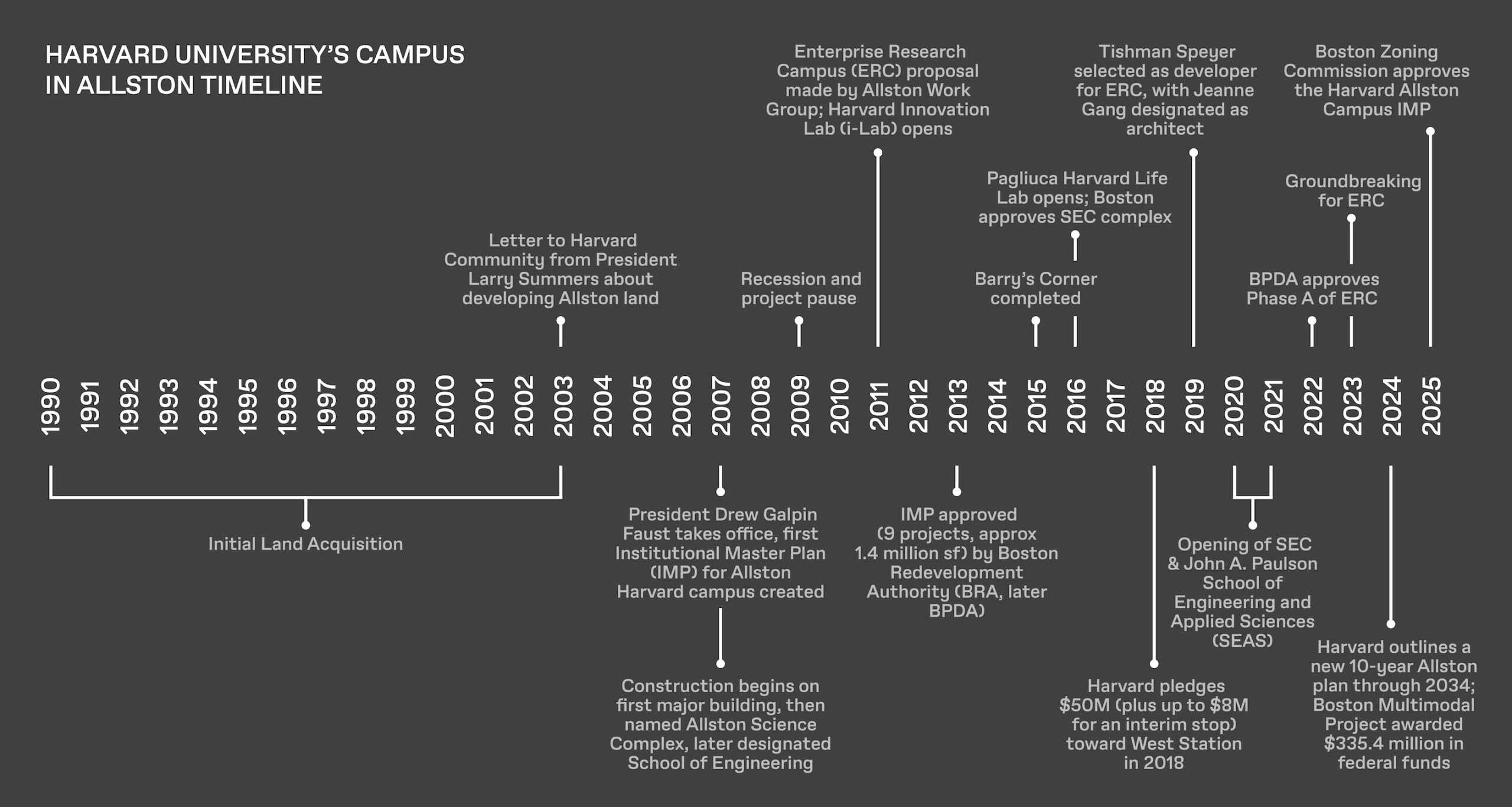

For nearly 50 years, Alex Krieger, professor in practice of urban design, emeritus, taught at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). For about half of those years, he was committed to helping Harvard in the development of the Allston campus , serving on work groups, task forces, and design review committees focused on the project. First working with Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers and his administration in the early 2000s, Krieger helped to initiate a master planning process that, through various iterations over the years, ushered in the Allston campus. The first phase of the Enterprise Research Campus is now nearing completion.

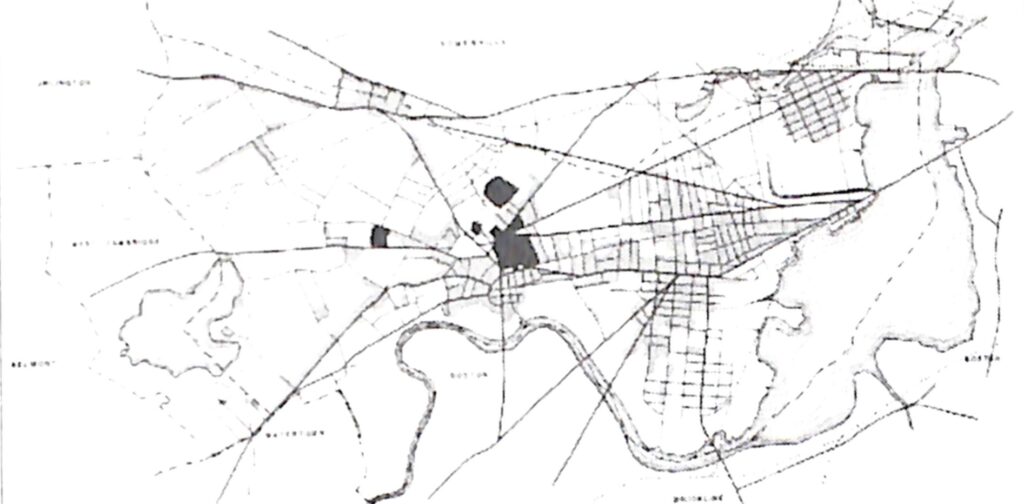

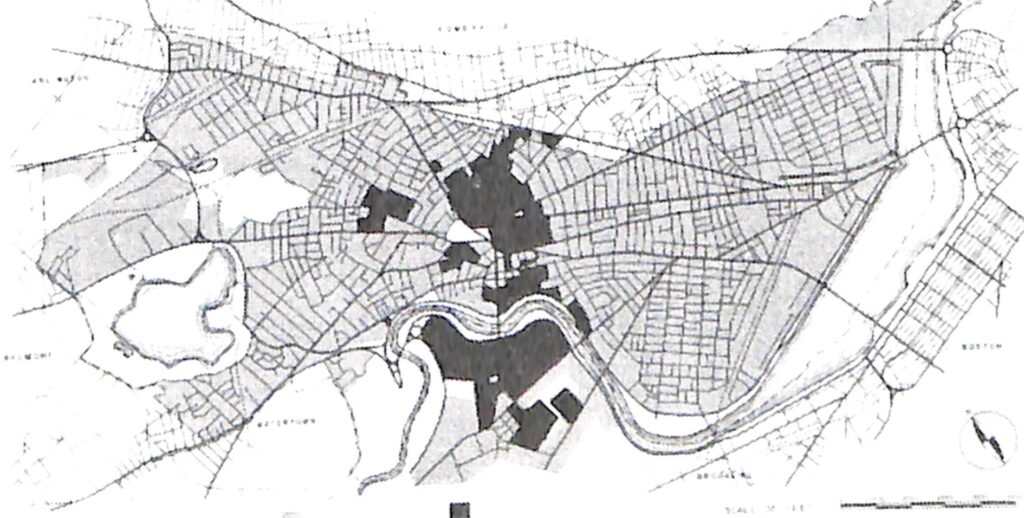

In addition to his scholarship, he’s well-known for his “iconic tour” of Boston that focuses on how the city, which was originally settled on an island, created land to accommodate its growth. He dedicated his career to the study of urbanism, with books including City on a Hill: Urban Idealism in America from the Puritans to the Present (2019), Urban Design (with William Saunders, 2009), and Mapping Boston (with David Cobb and Amy Turner, 1999).

Here, he recounts the history of the Allston campus and how he’s witnessed—and helped shape—its evolution into the landscape we see today, with the opening of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center , the “front door to the Enterprise Research Campus.”

How did the idea for a campus expansion originate?

Upon assuming the presidency, and with the then-recent public acknowledgment by the university that it had been acquiring land in Allston, Larry Summers announced the need for an ambitious master plan to prepare Harvard for its next decades of growth. He would reveal his own ambition that Allston would enable Harvard to establish “the Silicon Valley of the East,” given the university’s leadership in the sciences, and its researchers’ role in the mapping of the human genome that had just been completed by the International Human Genome Project. At the president’s direction, an international search for architects and planners ensued.

My first significant role was advising on the start of the overall planning process and becoming a member of the architect/planner selection committee for the master plan. I worked with Harvard Vice President for Administration Sally Zeckhauser, who directed the search process. We visited firms around the world, and in 2005, selected Cooper Robertson, Frank Gehry, and the Olin Partnership. At Sally Zeckhauser’s request, I began to serve on the design advisory committee as the master plan commenced and proceeded.

Concurrently, I was asked to develop initial programming guidelines for the future campus, which, late in 2005 was released as Programming for the Public Realm of the Harvard Allston Campus. The Cooper Robertson plan was made public in 2007. It gained much attention and publicity, even as we all knew that it would evolve significantly over the years. Several subsequent planning efforts with other planners followed.

When did construction in Allston begin?

The next significant event, in my memory, was the commissioning of the firm Behnisch Architeken, from Germany, to design what, in nine long years, would become the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. However, it was initially planned to be a research and teaching facility for continuing stem cell, genome and life/health sciences innovation. Again, I served on the architect selection committee and on the design review committee that followed.

The “Great Recession” of 2008-10 led to a substantial decline in Harvard’s endowment, and construction had slowed during 2009 and halted in 2010. Three underground levels had been built, intended for a large garage and a district energy facility. The District Energy Facility (DEF), was later built separately, designed by Andrea Leers of Leers Weinzapfel Associates, a frequent visiting faculty at the GSD. For much of the next five years, only the roof of those underground levels was visible, with four humongous construction cranes left idle and visible from afar. This was great fodder for The Boston Globe.

I remember; it was infamous. How long did it take for construction to get back on track?

Drew Galpin Faust became Harvard’s President in 2007. Because of the national economic downturn, she became less concerned with expanding Harvard and focused on projects such as the adaptation of Holyoke Center to a student union. In Allston, President Faust focused on the reuse of some of the properties left vacant by Harvard’s earlier acquisitions, helping to attract new tenants to provide neighborhood services and amenities.

Katie Lapp who became the Executive Vice President for Administration shortly following Zekhouser’s retirement in 2009, began to encourage President Faust to restart planning for Allston. I was part of various informal conversations about what to do with the unfinished project. A science facility had in the interim been built in Cambridge and so different uses needed to be identified before construction could resume.

There were various ideas. One thought was that one of the Longwood Medical Area (LMA) hospitals, or the School of Public Health might relocate to sit on top of the “shortest building,” since there was little space for additional growth at the LMA. Some might find that idea unlikely, but, at the time Chan Krieger & Associates was planning in the LMA, and I heard such conversations there, not just in Cambridge. Ultimately, of course, the Science and Engineering Complex (SEC)

, home of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), was the result.

There was also some discussion about a long-term future for Harvard’s acquisition of the Beacon Rail Yards and adjacent land under the Mass Pike, slated for eventual reconstruction. President Faust and Harvard leadership were becoming aware of just how much land was under Harvard’s control and cognizant that not all of it would be needed for Harvard’s academics.

How did the university decide they’d manage that land, and shift towards a new vision for the ERC?

These informal conversations and brainstorming sessions culminated in the formation of a new Allston planning committee, the Allston Work Team in 2010. I became one of the three co-chairs of that committee, along with Bill Purcell, former Mayor of Nashville, then at the Kennedy School, and Harvard Business School Professor Peter Tufano. The Work Team included the participation of most of Harvard’s Deans, Drew Faust herself, invited urban development experts, and of course, Katie Lapp.

Notions about a new kind of research campus, perhaps to compete with booming Kendall Square (which was beginning to be referred to as “the smartest square mile on the planet”) were already in the air. In Boston, Mayor Menino began to develop the concept of the Seaport Innovation Center. Underway were early phases of what, a decade later, would become the Cambridge Crossing innovation district, under the leadership of former Harvard planner Mark Johnson (MLAUD ’82). Harvard realized they’d better get into this game.

How did they balance community and university needs in the final design?

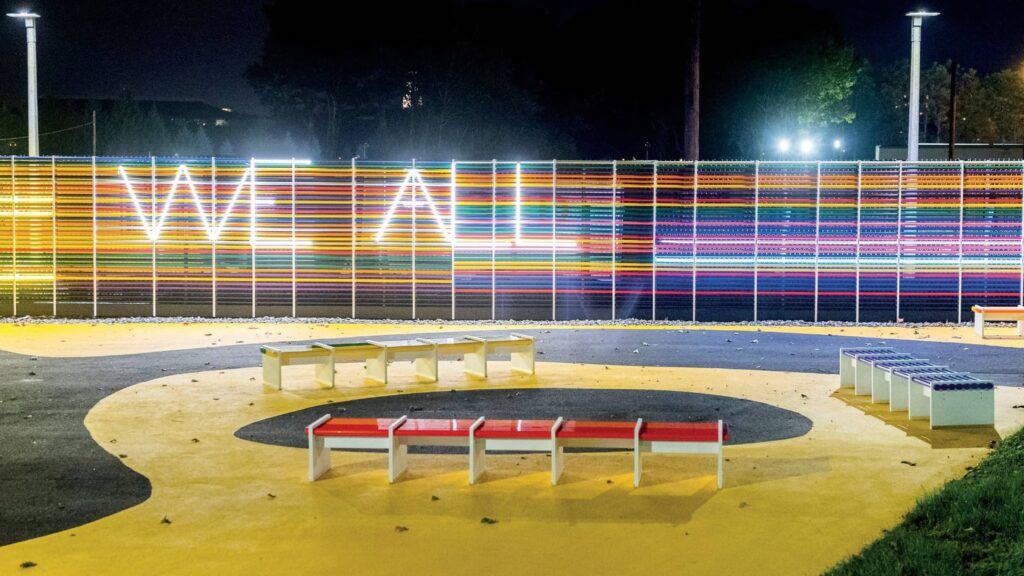

The Allston Work Team commenced serious discussion about what an Enterprise Research Campus (ERC) might become; supported the resumption of construction for what would become the Engineering School; initiated plans for graduate student and faculty housing, which led in 2015 to the Continuum Residences in Barry’s Corner, with Trader Joe’s at the base; explored how a needed hotel and conference center might become part of early phases; and continued exploring how to revive retail and community facilities around Barry’s Corner and along Western Avenue.

What can you tell us about the selection of Tishman Speyer

as the developer, and Jeanne Gang as the architect of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center

?

In 2018, Tom Glynn became the founding CEO of the Harvard Alston Land Company, and I helped Tom get up to speed on prior Allston planning efforts. We knew each other, as Chan Krieger had served Massport and earlier Partners Healthcare, both institutions he had led. We also had informal conversations about the Boston area development community, as, under his leadership, Harvard was getting closer and closer to proceeding with the selection of a development team for the ERC. I was not involved in that selection process but was quite pleased when Tishman Speyer announced that Jeanne Gang would play a major design role, including, of course, in the design of the Treehouse conference facility.

So, the Allston Work Team helped shape today’s Allston campus, with the November 2025 opening of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center, and the ERC now well underway

?

Yes, right now, Phase One is nearing completion, which encompasses nine acres. This first mixed-use cluster includes space for research, housing, a hotel, and the conference center. It will form “the prow” or “beacon” for future phases of the ERC, as the economy allows.

In 2010, the ERC

was just emerging as an idea, and seemed like a way to complement the future Science and Engineering Complex (SEC)

, once construction resumed. Behnisch Architekten

, the architect for the initial construction, had made the brilliant decision to maintain construction liability during those years. Without a building mass on top there was the possibility that those three unfinished levels would begin rising out of the ground due to groundwater hydrostatic pressure. So, it made sense to bring Behnisch Architekten back, though some at Harvard felt that the design was too modern and unlike Harvard. The building has acquired iconic status, and as Stefan Behnisch promised, is one of the world’s most energy efficient science facilities.

I remained on the design review committee for the project, alongside former GSD Dean Mohsen Mostavi, and later Jeanne Gang, as well.

How would you characterize Harvard’s relationship with the Allston community?

The relationship

has improved over time, beginning rather badlywhen it was first revealed that Harvard had secretly bought 52.6 acres of Allston land in the late 1980s and 1990s

. Harvard has since substantially invested in Allston especially along the Western Avenue corridor. As I mentioned, President Faust and Katie Lapp began to focus more attention on neighborhood concerns and needs, and this has continued under Presidents Bacow and Garber.

Of course, expressions of impatience on the part of the Allston community remain, citizens always asking Harvard to reveal any additional plans, plus deliver on some now-old promises. For example, mention the Greenway, and residents will say, ‘Those Harvard people, they promised that to us two decades ago.’ Indeed, a greenway was identified in the initial Cooper Robertson master plan, a continuous pedestrian park-like corridor from the Allston Public Library to the Charles River. Parts of it have been realized, but one long segment remains missing.

The ERC is adding a segment at its center; it is beautifully designed. The trouble is, this segment is separated from the portions of the Greenway that exist, by those not yet built. As the ERC fills with users and tenants, it may make this space seem like it’s proprietary to the ERC. Allston folks may not understand that it’s part of the long-promised Greenway, until Harvard builds the rest of it. I’ve been very vocal about this issue, to the point where everyone was sick of hearing it. Harvard will soon, I hope, complete the missing segments and it will all turn out okay.

Harvard deserves more credit than it sometimes gets from Allston neighbors. As far as I know, Harvard has committed something like $50 million at least three times—once for the Beacon Yards transit station

. The current ten-year Allston plan promises an additional $53 million in community benefits. Another large sum is slated towards the reconstruction of the Turnpike. Finally, less publicly so far, another $50 million-or-so has been quietly promised for the eventual realignment of a portion of Storrow Drive to enable the widening of the Esplanade along the Charles River.

How do you feel about handing off the Allston project, now that you’ve stepped back from the planning process?

Well, I still get to offer opinions, such as pressing the Business School to do something with its huge parking lot right across the street from the ERC, and cajoling Harvard to complete the Greenway. My last role was to serve on the design review committee for the A.R.T. project. This will be a truly wonderful addition to North Harvard Street and Barry’s Corner. The Allston Campus and the revitalization of the Allston neighborhood are progressing well.