This summer, Graduate School of Design (GSD) students Michael Anthony Bryan II (MLA ’26) and Tyler White (MDes, MUP ’26) traveled a humid path through rural Virginia and Texas to document Black landscapes, delving into historic records, oral histories, and the built environment for clues to the past. They were among the GSD students whose research was supported by the Penny White Project Fund.

The funding allowed White and Bryan to join a three-day trip organized by Rutgers’ Black Ecologies Lab in Richmond and Tappahonnack, Virginia, to study, as the Lab explains, “Indigenous (Rappahannock) and Afro-Virginian practices of place, land, and water stewardship…,” and then, employing similar research methods, they traveled through Texas on their own. They chronicled their journey with audio recordings and photography, creating an archive of images and maps to document sites where Black people designed and built landscapes.

Their work is now on display at the GSD in the student-run Quotes Gallery

, alongside documentation of other student projects supported by the Penny White Project Fund.

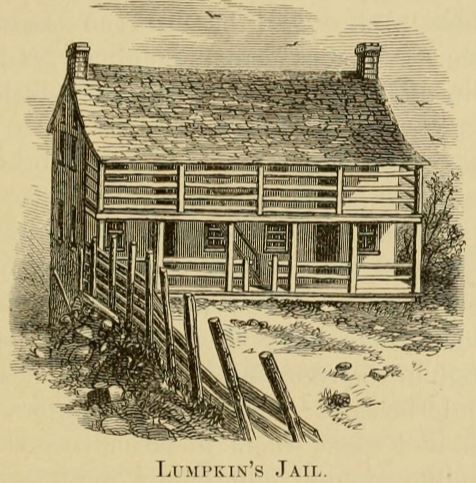

In Virginia, the group observed Indigenous canoe-making and visited the place where the Lumpkin Slave Jail once stood. A highway overpass runs above a few fallen cement blocks on the grassy soil, a small sign marking the spot that’s now part of the Richmond Slave Trail. Nearby, over the remainder of the site, a perfectly manicured grassy field stretches vacant and quiet. In the 19th century, enslaved people were imprisoned at the jail before their sale.

“I was left with this profound feeling,” said Bryan, “of the fact that there are all these spaces where our ancestors lived, and their lives have been glossed over. The only evidence of their existence is one or two stones on the site, or a marker that acknowledges that people have died here. There are so many stories there that will never be uncovered, never be told.”

Bryan and White encountered more traces of such stories when they continued their journey in Texas, a state they chose for its relatively well-preserved freedmen’s towns, settlements established in the 19th century by formerly enslaved people. They note that they witnessed “a staircase to nothing in Houston’s Freedmen’s Town ,” as well as “mounds poking up out of the earth in a cemetery behind a Best Inn in Galveston, and blocked access all along the rockiest most industrial parts of the Rappahannock River…”

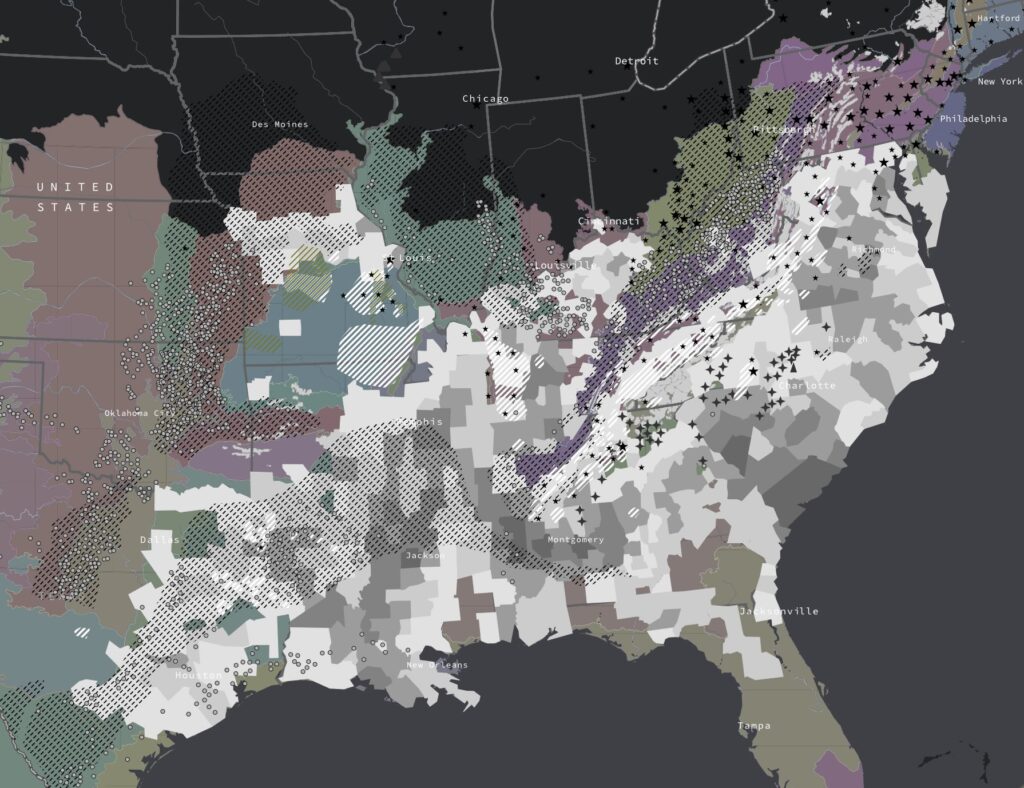

Upon their return, they made a series of maps that mark the places they visited, creating connections to other sites around Virginia and Texas. They also compiled an annotated almanac of archival photographs and news stories of Black peoples’ lives and experiences. The pair explain that this research is grounded in the interdisciplinary fields of Black geographies

and Black ecologies

, the latter of which “explores the historical and contemporary relationships between Black people, land, and the environment,”[1]

and rose out of courses they took at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). Sarah Zwede’s “Cotton Kingdom, Now,” for example, revisited Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1852 journey through the American South, and Thaisa Way’s “History of Landscape Architecture,” examined the cultural and historical significance of gardens and landscapes.

White noted that his perspective shifted as he traveled and read about enslavement in the context of David Silkenat’s Scars on the Land

. “I learned so much about slaves being involved in mining—lead and iron ore mining,” said White, “and how often slaves were being hired out for work. In urban spaces, so many slaves were doing industrial activities alongside people who were not enslaved, troubling, for me, the idea of class and labor relations.”

The landscapes they visited held evidence of the labor that shaped the spaces, but, while some were well-maintained, others had been neglected. “We went to a spot in Galveston, Texas, and found a hidden cemetery that was surrounded on all sides by motels, at the bottom of a flood basin,” said Bryan. “The mosquitoes and bugs were eating us alive.” He turned to Toni Morrison’s writing about water forever returning to its source, integrating her words into the map of flood zones in Texas to ask how we can “care for spaces that are also continuously under threat with climate change and rising waters,” and manage urban systems that are “falling under their own weight” with an influx of “stormwater, flooding, and infrastructure issues.” With that environmental degradation, he explains, we lose these sites of memory that hold evidence of past lives and their design contributions.

In addition to traveling to to document Black architecture, White and Bryan have also worked at the GSD to recognize and document the school’s Black designers. In February, 2025, they co-curated “Architecture in Black,

” an event during which attendees examined various archival documents and publications in the Special Collections Reading Room at the GSD’s Frances Loeb Library. The event, part of a series of “archives parties” hosted by special collections curator Inés Zalduendo, was curated in collaboration with the African American Student Union (AASU), and supported in part by the GSD’s Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund.

“Architecture in Black,” named after Darrell Fields’ book , which “demonstrate[es] the ‘black vernacular’ in contemporary architectural theory,” examined materials that, Bryan and White explain, speak to “how Black GSD Alumni have conceptualized, devised, and produced architecture from and within Blackness.” They highlighted objects such as Fields’ 1993 publication of “A Black Manifesto” in the Harvard journal APPENDIX: Culture/Theory/Praxis , Audrey Soodoo Raphael’s GSD thesis “From Kemet to Harlem and back: cultural survivals and transformations;” Nathaniel Quincy Belcher’s thesis “Taking a Riff;” and Sean Anderson and Mabel O. Wilson’s book Reconstructions: architecture and Blackness in America.

White explained that one of the goals for their trip to the South was to “bring attention and activity back to these spaces.” The archives party served a similar purpose, bringing together students, faculty, and staff to discuss historic Black designers at the GSD. As they wrap up their penultimate semester at the GSD this fall, Bryan and White plan to continue to recognize the people whose design sensibilities and labor created our contemporary expression of architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design and planning.

[1]

“Historian J.T. Roane Explores Black Ecologies,” emerald faith rutledge, JSTOR Daily, February 14, 2024. https://daily.jstor.org/historian-j-t-roane-explores-black-ecologies/