Julia Thayne , Loeb Fellow 2026 and Founding Partner of Twoº & Rising , recently delivered the keynote lecture at the Harvard Business School’s Climate Symposium , where she spoke about cities as catalysts for climate action. Her previous work at climate NGO Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office, and global company Siemens focused on how first-of-a-kind sustainable projects create tipping points for change at scale. Now, as a Loeb Fellow at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), she is applying that experience to research how cities meet their sustainability targets, while adapting to climate change. We met in Gund Hall to talk about her keynote and the work she’s undertaking at the GSD this year, including a new research project on the environmental and social impacts of hyperscale data centers in the U.S.

What is your research here at Harvard, as a Loeb Fellow, focused on?

In general, I’m looking at how cities are meeting their sustainability targets, or not, what that teaches us about where we need to focus moving forward, and how they’re also starting to incorporate more action around adaptation and resilience.

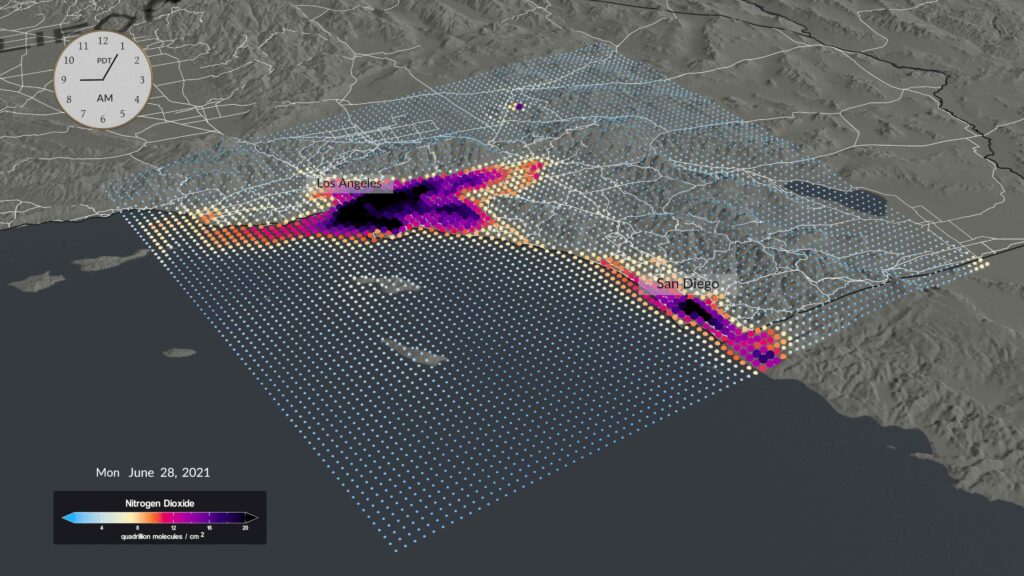

Like many others in climate, though, I’m also taking on a new research project on data centers in the U.S. They already consume a large amount of energy, and are projected to consume even more (in some states as much as 39 percent of total power). They’re polarizing in terms of their impacts. The research I’ve seen so far at Harvard has primarily been about data centers’ power consumption: how do you reduce it, what impacts does it have on investments in the grid, and will the public have to bear the costs of these upgrades. There are some excellent papers out on these topics by experts at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and Harvard Law School, for example.

Along with Robert G. Stone Professor of Sociology Jason Beckfield, and Harvard College undergraduates Brady McNamara, Hailey Akey, and Julie Lopez, and with the support of a Salata Institute Seed Grant , I’ve taken on a research project from a slightly different angle: how do you optimize the environmental and social impacts of future hyperscale data centers in the U.S. that are being built near communities. Our goal is educate people about the impacts, give policy makers and communities ways to shape them, and ultimately affect how these data centers roll out so that they do have benefits.

Fortunately, as I’ve started on this research, I’ve also found the incredible GSD faculty and alumni who’ve been working on this topic for years, like Marina Otero and Tom Oslund. Already, we’ve been discussing how their landscape and architecture designs and practice are shaping what’s being built inside and outside the U.S.

Many of these centers are being constructed right now. How will you intervene in that system?

Remarkably, there are five companies who are primarily responsible for somewhere around one third of new large-scale data center construction. Five. If you can affect the way they think about data center siting, design, community engagements, and impacts, you can affect one third of what’s being built, which translates to hundreds of billions of dollars of investment. That’s pretty wild.

While the deliverables for our research grant are to create primers for key stakeholders, like developers, community groups, and policymakers, to inform actions that could optimize data center development, our ambition is to collaborate with the many others—at Harvard and beyond—who are trying to make sure that the best decisions possible are made around how data centers get built in our country. The development process is remarkably similar company-to-company. A real estate site selection team chooses sites based on power availability and land prices. The engineers help dictate the data center building design based on server needs, power, cooling, and time to construction. Then a team of architects, landscape architects, and engineers collaborate to optimize the design before—or sometimes as—construction is happening.

This is where my experiences in local government, huge tech companies, and research non-profits are coming in handy. I’ve written local policy that helps shape where things get built. I’ve managed tech projects and worked alongside engineers and technologists (usually as the only economist and urban designer in the room). My job at RMI was to think about where the intervention points were for changing systems. For example, how do you pinpoint the change that needs to happen that’ll affect not just one development, but many? So, in a strange way I’ve been preparing for this moment for my whole career, even though I didn’t know it would come.

In some ways, it’s a deeply personal ambition. My family lives in a small city that’s currently grappling with how data center development might affect their local economy and quality of life. In fact, my mom has been a very valuable primary source of information around data center development, sending me local news articles that are guiding some of the ways we’re doing our research! And my niece and nephew, ages 7 and 1, are who I do the work for, always.

Your keynote for the Harvard Business School’s Climate Symposium focused on the work you’ve done across your career on cities?

Exactly. The Harvard Business School (HBS) student groups organizing this year’s Climate Symposium wanted a nontraditional keynote to kick-off the event—somebody with a different perspective than the one they’re normally taught or exposed to at HBS. They gave me a broad topic: “Cities as Catalysts to Climate Action.” I used it as an opportunity to look at why cities are so important to climate action, what they’re doing, and how that has played out (well and poorly) in my own experiences in LA.

Cities are essential to climate action, because they’re the problem—and also hold the keys to the solution. Cities are responsible for roughly 70 percent of the world’s CO2 and methane emissions. They are where people live, work, and spend money. They also bear the brunt of climate change. So, in many ways, cities are both forced and choose to act on mitigation (how you reduce the impacts of human life on climate change) and on adaptation (how you adapt to the ways our climate is changing).

You see that everywhere, from Mexico City, where they’ve greatly expanded their bike and bus rapid transit networks to enhance road safety and give people affordable mobility, to Jakarta, where 40 percent of the city is below sea level and 33 million people are figuring out ways to continue living in the region.

You also see it in LA, where I’ve been living and working for the past 10 years.

What’s happening in LA that makes it different from other cities?

LA was part of the first wave of cities setting ambitious targets around carbon reduction: 50 percent emissions reduction by 2025, zero carbon by 2050. It’s hard to underscore enough that when those targets were set, we had no idea if we could achieve them! I mean, we had plans and models showing how we might achieve them, but as anyone who’s worked in local government knows, plans are very different than reality.

What’s noteworthy is that by 2022, LA had reduced emissions by 20 to 30 percent off the 2025 target, yes, but still—when you think about how hard we make sustainability sound (and how hard it is in practice), it’s pretty impressive. What’s even more impressive is that LA was only 1 percent off the target they set for their own municipal operations. That means what the local government could directly control, they were able to measure and manage. And what’s most impressive is that LA’s economy grew over that time. So, economic growth and environmental harm were essentially de-coupled.

Where was LA not able to meet its targets, and how does that reflect what other cities have done?

Cities generally do five things on climate action. They change where their electricity comes from by incorporating more renewable sources of energy. They reduce the amount of energy they consume, especially in buildings. They shift people and things to more sustainable modes of transportation, like public transit or zero-emissions trucks. They try to reduce waste by not creating it in the first place or re-using it. And, increasingly, they’re adapting to life with different weather conditions.

LA did really well on increasing the amount of renewables in their electricity mix, mainly by investing in big renewable infrastructure projects in and out of the state and changing up how people can buy renewable energy. LA also benefits from (right now) a mild climate where energy efficiency in buildings is easier. The city owns its own port and airports, too, so it was able to control more effectively emissions and pollution from those sources (though they’re definitely still not zero).

They did not do well on people’s mobility, though, or on waste. Some people might chalk that up to bad policy and politics or to something abstract, like “the difficulty of behavioral change,” but I think you have to look deeper. Historical decisions on land use, the lack of readily available and attractive mobility options, inadequate systems and information and accountability about waste, and LA’s importance as both industrial and urban centers – these are critical aspects of LA’s climate story, and they have to be considered when you’re thinking about how to take action on a topic as interdisciplinary and interconnected as climate.

What is your firm, Twoº & Rising, doing to help LA and other cities course correct on climate action?

My business partner and I started Twoº & Rising almost two years ago. We wanted to work with governments, companies, start-ups, investors, and organizations to accelerate the deployment of cleantech solutions in the U.S. “Twoº” is a reference to the Paris Agreement and the goal to keep global warming to 2 degrees by 2030.

Our work in LA specifically has been a lot about mobility, and this idea of giving people mobility options so that they don’t have to rely on cars—and also about adaptation and resilience, a huge and growing topic in the region.

LA is trying to use a series of upcoming global sporting events, like the 2028 Olympic & Paralympic Games, as tipping points for Angelenos to experience getting around the region without their own cars. We’re trying to capitalize on that moment by teaming up with local transportation agencies, as well as foreign start-ups and companies, who can offer high-quality, more affordable, safer ways to experience the city without its legendary traffic.

Similarly, my business partner and I both were temporarily by the LA wildfires in January (him by Eaton, me by Palisades), and are passionate about helping to find solutions to prevent them and to be resilient if and when they do happen. We worked on a project around providing grid resilience during public safety power shut-offs.

What do you hope students here at the GSD would think about in terms of sustainability?

I’ve explicitly devoted my career to climate. At the beginning, I don’t know that’s what I was doing, but now when I sit back, I realize it’s my calling. For some of you, that’ll also be your calling; for others, it’ll be something else. But whether you’re a “housing” person or a “public health” person or a “women’s rights” person or an “economic development” person, I hope you know that you also are, or can also be, a “climate” person. What you’re doing is inextricably linked to the climate and context it’s in, just as what I’m doing on climate is also inextricably linked to housing, public health, social justice, and economic growth or decline. If we can be mindful and intentional about that, we can stop considering these topics as trade-offs and start realizing just how supportive they are of each other.