What is driving the surge of incidents in which white people have called the police to report Black people who are simply going about their business—hanging out at Starbucks, birding in Central Park, or as was the case recently for a small group of middle-class Black women, talking too loudly on a train in California wine country.

Part of the answer has to do with the ubiquity of cell phones, which facilitate rapid reporting of racial incidents to police and the news media, along with social media, which bring news of the same incidents to the public with nearly equal speed. Yet there is also a sociological explanation.

White people typically avoid the Black space, but Black people are required to navigate the white space as a condition of their existence.

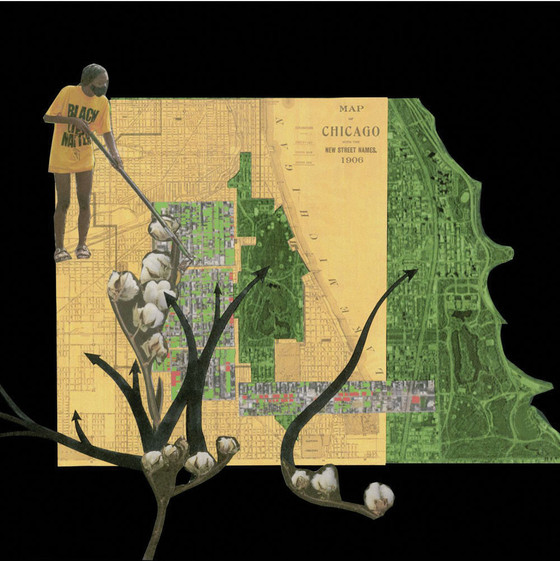

And many white people have not adjusted to the idea that Black people now appear more often in “white spaces”—especially in places of privilege, power, and prestige—or just in places where they were historically unwelcome. When Black people do appear in such places, and do not show what may be regarded as “proper” deference, some white people want them out. Subconsciously or explicitly, they want to assign or banish them to a place I have called the “iconic ghetto”—to the stereotypical space in which they think all Black people belong, a segregated space for second-class citizens.

A lag between the rapidity of Black progress and white acceptance of that progress is responsible for this impulse. It was exacerbated by the previous presidential administration, which emboldened white racists with its racially charged rhetoric and exclusionist immigration policies.

Over the past half-century, the United States has undergone a profound racial incorporation process that has resulted in the largest Black middle class in history—a population that no longer feels obligated to stay in historically “Black” spaces, or to defer to white people. When members of this Black middle class (and other darker-skinned Americans, too) appear in civil society today, and especially in “white” spaces, they often demand a regard that accords with their rights, obligations, and duties as full citizens of the United States of America.

Yet many white people fundamentally reject that Black people are owed such regard, and indeed often feel that their own rights and social statuses have somehow been abrogated by contemporary racial inclusion. They seek to push back on the recent progress in race relations, and may demand deference on the basis of white skin privilege.

As these whites observe Black people navigating the “white,” privileged spaces of our society, they experience a sense of loss or a certain amount of cognitive dissonance. They may feel an acute need to “correct” what is before their eyes, to square things, or to set the “erroneous” picture right—to reestablish cognitive consonance. White people need to put the Black interlopers in their place, literally and figuratively. Black people must have their behavior corrected, and they must be directed back to “their” neighborhoods and designated social spaces.

Not bold enough to try to accomplish this feat alone, many of these self-appointed color-line monitors seek help from wherever they can find it—from the police, for instance. The “interlopers” may simply want to visit their condo’s swimming pool, or to sit in Starbucks or meet friends there before ordering drinks, something white people typically do without a second thought, or take a nap in a student dorm common room, make a purchase in an upscale store, or jog through a “white” neighborhood.

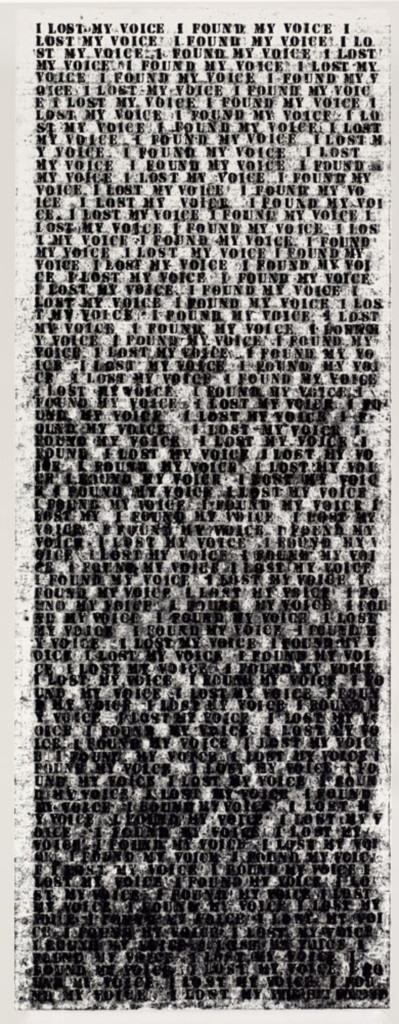

For the offense of straying—for engaging in ordinary behavior in public and being Black at the same time—they incur the “white gaze” along with a call to the police. And we all know what can happen then. When the police have killed Black people—which seems epidemic—they have almost never been held accountable. The George Floyd case was an exception.

In times past, before the civil rights revolution, the color line was more clearly marked. Both white and Black people knew their “place,” and for the most part, observed it. When people crossed that line—Black people, anyway—they faced legal penalties or extrajudicial violence. In those times, to live while Black was to be American and nominally free but to reside firmly within a virtual color caste—essentially, to live behind the veil, as W.E.B. Du Bois put it in The Souls of Black Folk.

Continue reading on the Harvard Design Magazine website…

“The Perpetual Stranger” by Elijah Anderson is excerpted from Issue No. 49 of Harvard Design Magazine: Publics. It has been adapted by the author from his new book, Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life (University of Chicago Press, 2021).