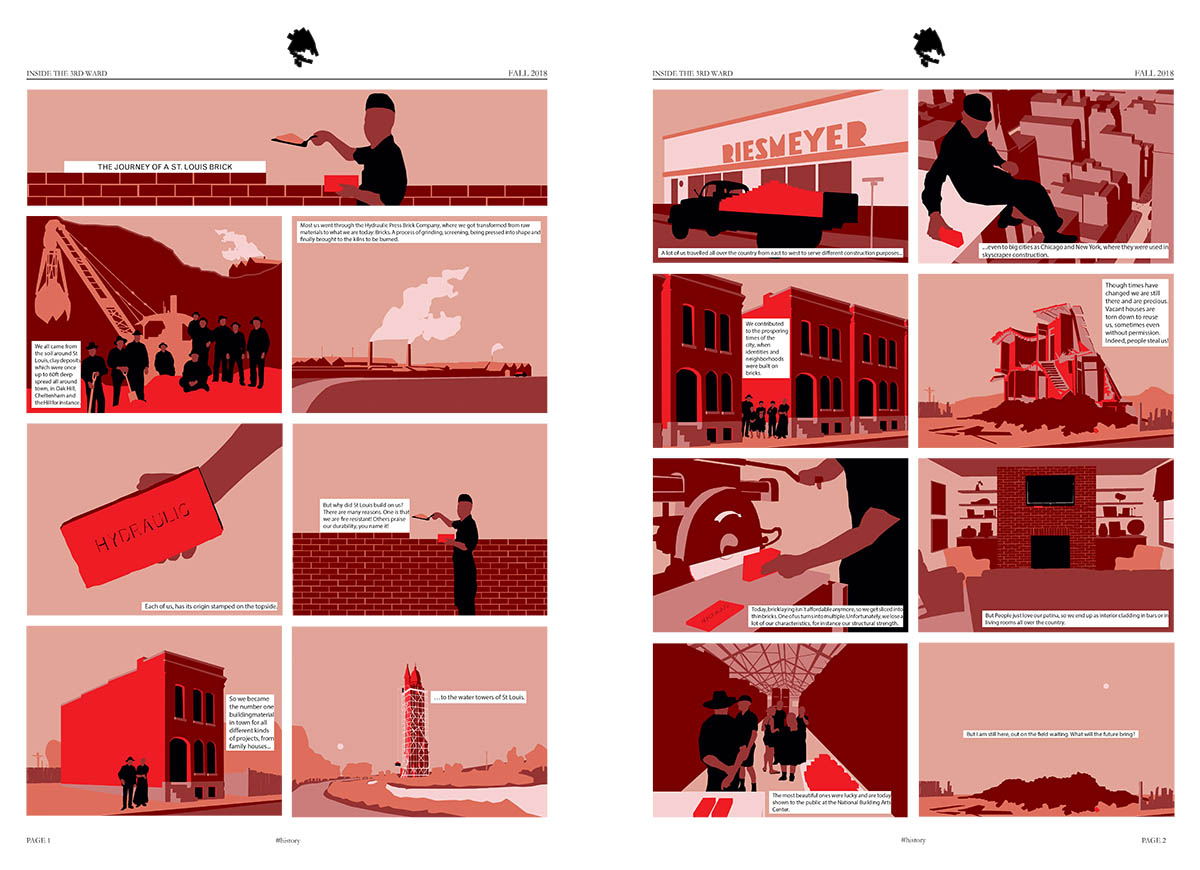

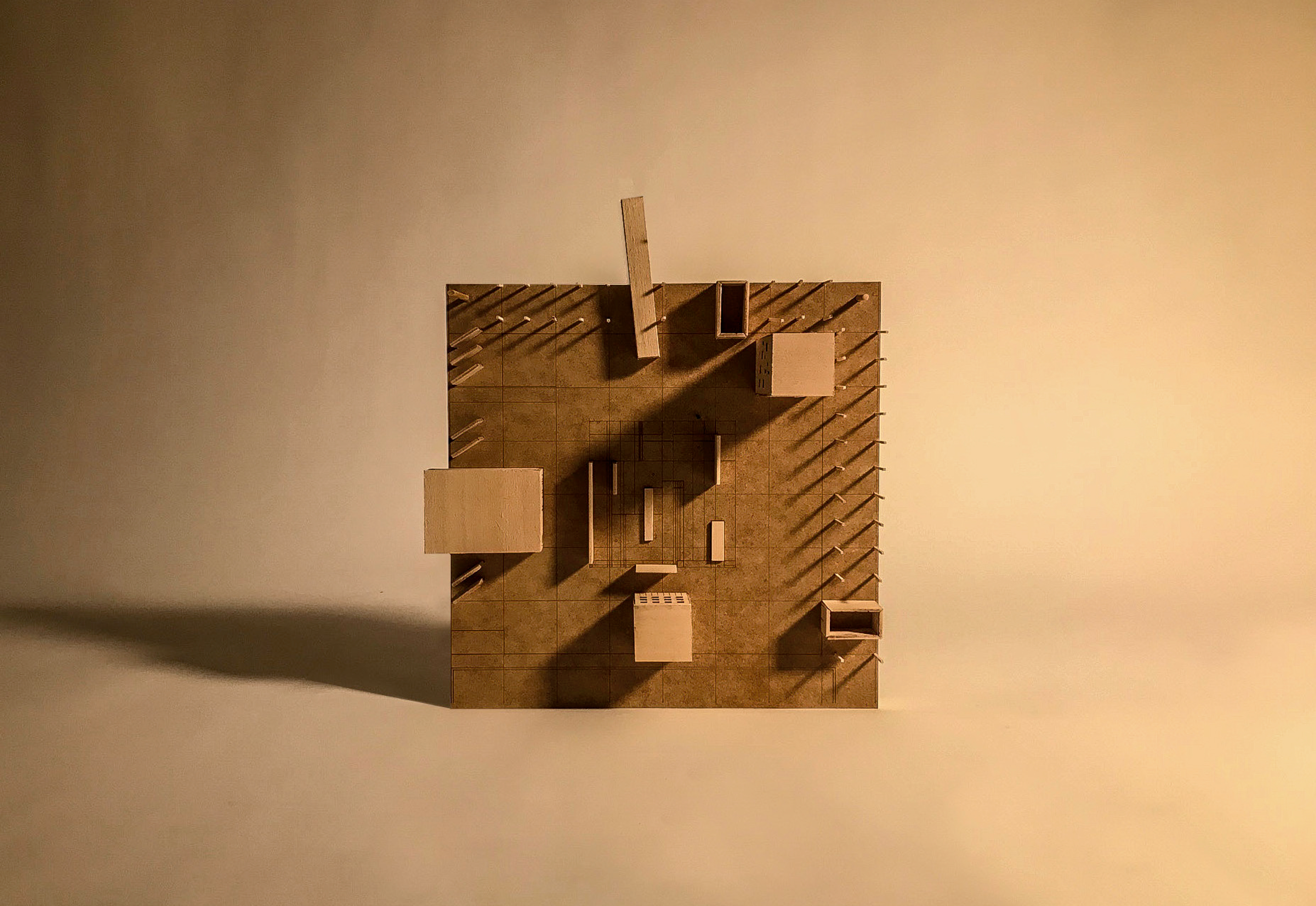

STL Brick Bank

Jakob Junghanss (ETH Zurich Exchange Program)

In the last decades, St. Louis’ built legacy has been increasingly challenged by rising vacancies. This has shaped many neighborhoods’ appearances, including the Third Ward. Demolition and material salvage emerged as strategies to address this issue, while providing job opportunities for local citizens. But how do these markets operate and what happens to the materials, such as the famous St. Louis bricks?

Today, salvaged bricks leave the neighborhood with the demolition companies, entering a booming market of reclaimed materials all over the country. St. Louis bricks are a popular reclaimed good; currently two bricks are being traded for one dollar. Considering that a vacant house can be bought for $1,000, built out of approximately 40,000 bricks, it seems that the material value of a disassembled house is more than that of an intact one.

This project wants to emphasize that the neighborhood should contribute and benefit from the material flows and their revenues. Otherwise the community is not just losing the bricks as an essential part of their built heritage, but also not profiting from the reclaimed brick business.

The proposal–a cooperative brick bank for the Third Ward–transforms salvaged bricks into an asset for the community. Storing bricks locally enables the community to invest into the salvaged material market, as well as ensuring that the bricks and their history are staying in the Ward. A loose storage–the checking account–provides brick traders on a daily basis, while a solid masonry structure–the savings account (also defining the brick banks appearance)–offers a long term asset. The brick bank is anchored in the neighborhood, offering proximate institutions a space to activate and engage with the neighborhood. Depending on the salvage brick market, the appearance of the brick bank is constantly evolving.

A Monastery in Framingham

Nicolás Delgado Álcega (MArch II ’20)

Set in 2048, the monastery is a home base for the pursuit of meaning. It is one more world amidst a context, not a model. It is a proud position, not a retreat.

The monastery is built upon the physical remains of yet another world. It produces a new future for the existing urban objects on the Framingham site in an anciently fresh way.

The monastery is built by quarrying material within the city. A resource is understood as a material we invent a use for because we know it. The monastery is built from the remains of a highway intersection being demolished nearby. Principally, concrete rubble and granite curbs. There is more thinking and less toiling. Little is wasted. A new kind of craft emerges.

The common Bath is a fundamental component of life in the monastery. It is communal, and yet deeply about the self and body. The spaces in the Bath are sequential but open; available for a couple of minutes with one’s mind elsewhere, or for much longer than that, immersed in sense perception and feeling.

The Bath is not hermetic. It lets lights travel into the spaces; it accepts the entry of unexpected sounds; it reverberates certain movements from the exterior, sometimes. It is a deeply internal space that nonetheless makes one aware of the forces of that which we call the ‘exterior’; what we only understand as shadows in the walls of the cave because they exist outside of the ‘world’ we have built.

Halftone Blur

Estelle Yoon (MArch I ’20)

The project attempts to translate the depth of a 3D form in a digital environment into a graphic code that is mapped onto the form itself. The extra layer of graphic alters the perception of the form – the z-depth information turns into halftone and registers an uninterrupted graphic from a favored elevational view, or the “front” of the object. When turned around, the dots start to stretch and morph into something entirely different than the implications of the original graphic, in a way that responds to the angle and depth of the lateral surfaces it sits on but also unexpectedly in the misalignments of the graphic and the volume. The unconsidered sides, or the “back,” starts to reveal the assembly logic of the form and its thinness. The formal aspiration lies in colliding volumetric aggregate in various orientations with a rigid cubic surface – setting up a relationship between object and frame, favored view vs others. The process learns its method of applying imagery on volume from hydro-dripping.

Maison Héroine

Tasos Giannakopoulos (MArch II ’19)

A future has arrived. The year is 2048 and automation has resolved all of issues of labor on behalf of humans. Time is abundant. Spaces designated for work have become obsolete. Metropoles and their concomitant working opportunities have become irrelevant. A massive flee towards the countryside is evident. Housing is urgent. How does one live when there is no work to be done? How does architecture respond to such a crisis?

The time of the engineer is a faraway echo in 2048. The time of the poet has arrived. People do what they have always been doing when labour was being taken care of; they philosophize, they make art and have sex. Architecture is the medium though which the desire for free, unconstrained creation from every institution and authority is fulfilled. A superblock of nine housing units each arranged around a central garden is the prototype that is proposed. Public rooms with functions that constitute the everyday rituals of this new reality fill the ground floor in various arrangements. One occupies rooms instead of apartments scattered around the blocks in the way that fits their own personal lifestyle. An excessively stimulating urban environment is created. The linear narrative is no longer available. The spatial hyperlink has been fulfilled. Forms from the heroic Modernist age are appropriated shamelessly. La Tourette is mass produced and calls forth these new followers to match their spaces of dwelling with their way of living.

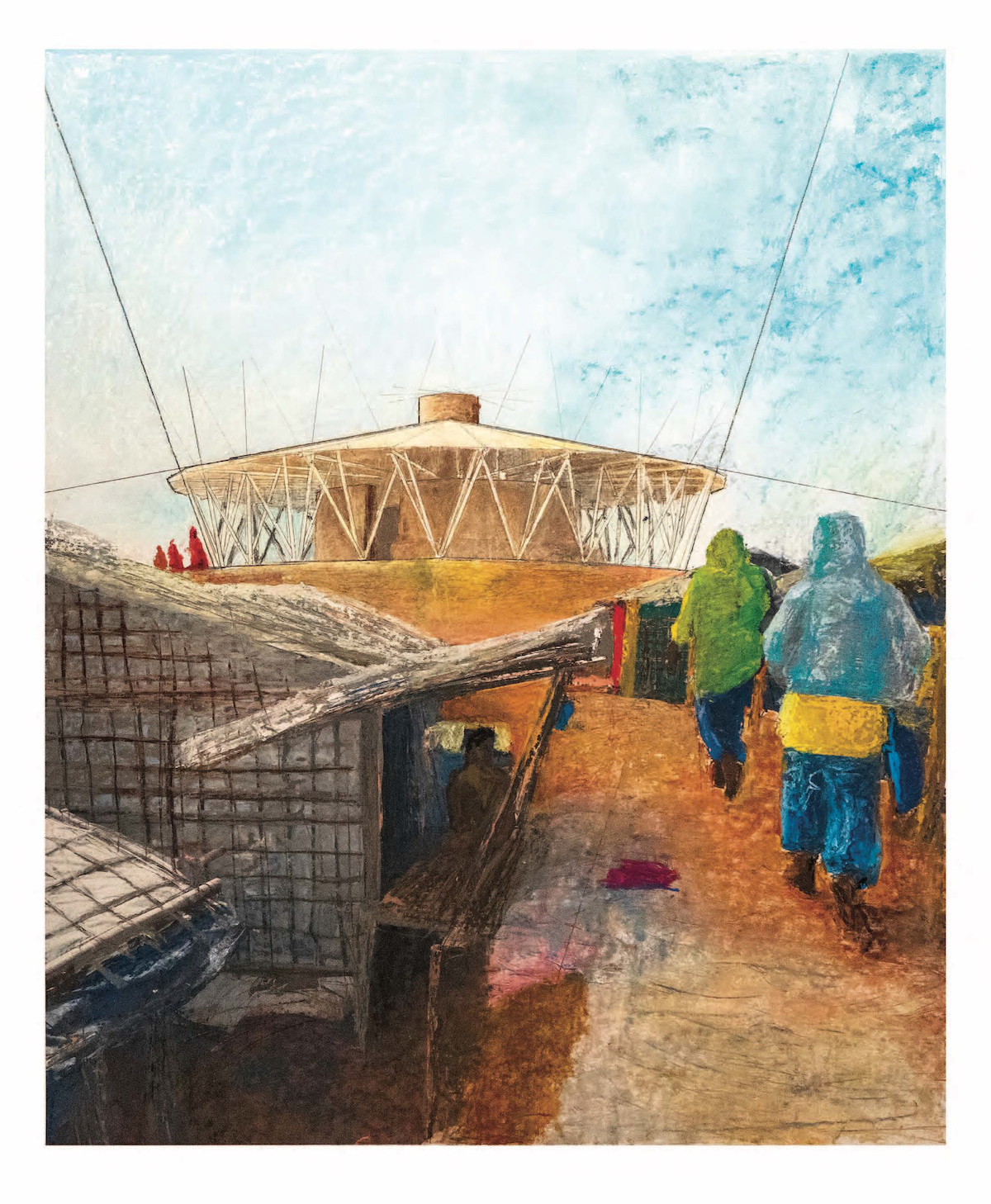

Living is Form

John Wagner (MArch II ’19)

Among the extents of international human aid facilitated by the United Nations High Council on Refugees and the International Organization for Migration, intervention strategies are characterized by utilitarian means, and a stark semblance of society, expression is supplanted by mere sustenance. Could instead an artistic or architectural intervention engage residents of this camp, who endure an indeterminate duration of temporary occupation, in a constructive conversation of how space and form could be organized to meaningfully counteract their experience of a suspended state of dwelling? Could the installation itself become a method of healing of traumatic experience? As an ephemeral construction, could the event of its installation serve as a memory vessel, demarcating a moment at the outset of an indeterminate future timeline, formulating the core of new spaces of solidarity?

While directly addressing the corporal needs of refugees, may this intervention also itself be a process by which primary trauma may be comforted and ongoing traumas of camp be mitigated? Can the art intervention, in form and in process of conception, be itself both a memory device, a symbolic device, and a therapeutic device? With reference to the conceptual provocation Brian Holmes identifies in Eventwork, social movements “are vehicles to change the forms in which we are living.” Within the exceptional circumstance of the camp, can a design intervention to address an essential need itself be a vehicle to change the condition of subsiding within the camp?

Adopting the position that art and architecture can expand beyond the object, the argument of the intervening project Living is Form seeks to reveal how a process of creating and shading a public space could be means to enable and empower a community to conceive, organize, implement and maintain their own environment.

Taking the form of three urgent need areas, Living is Form materializes as an improvisational sunshade for delineating public space, a prototypical community kitchen for engendering third spaces in camp neighborhoods, and a street trellis that serves as a platform for agricultural nursery, provisional sunshade, and readily appropriated framework for privacy screens.

Each of the designs is intended as a pattern, script, or readily appropriated building form that enables residents to create, augment, or appropriate spaces within the camp. The method of implementation is through community engagement and outreach, a new conception of space within the camp may be realized. The physical spaces delineated by these object(s) of intervention become a focal point around which new social configurations and realities can condensate, engendering a new condition of empowerment of the refugee.

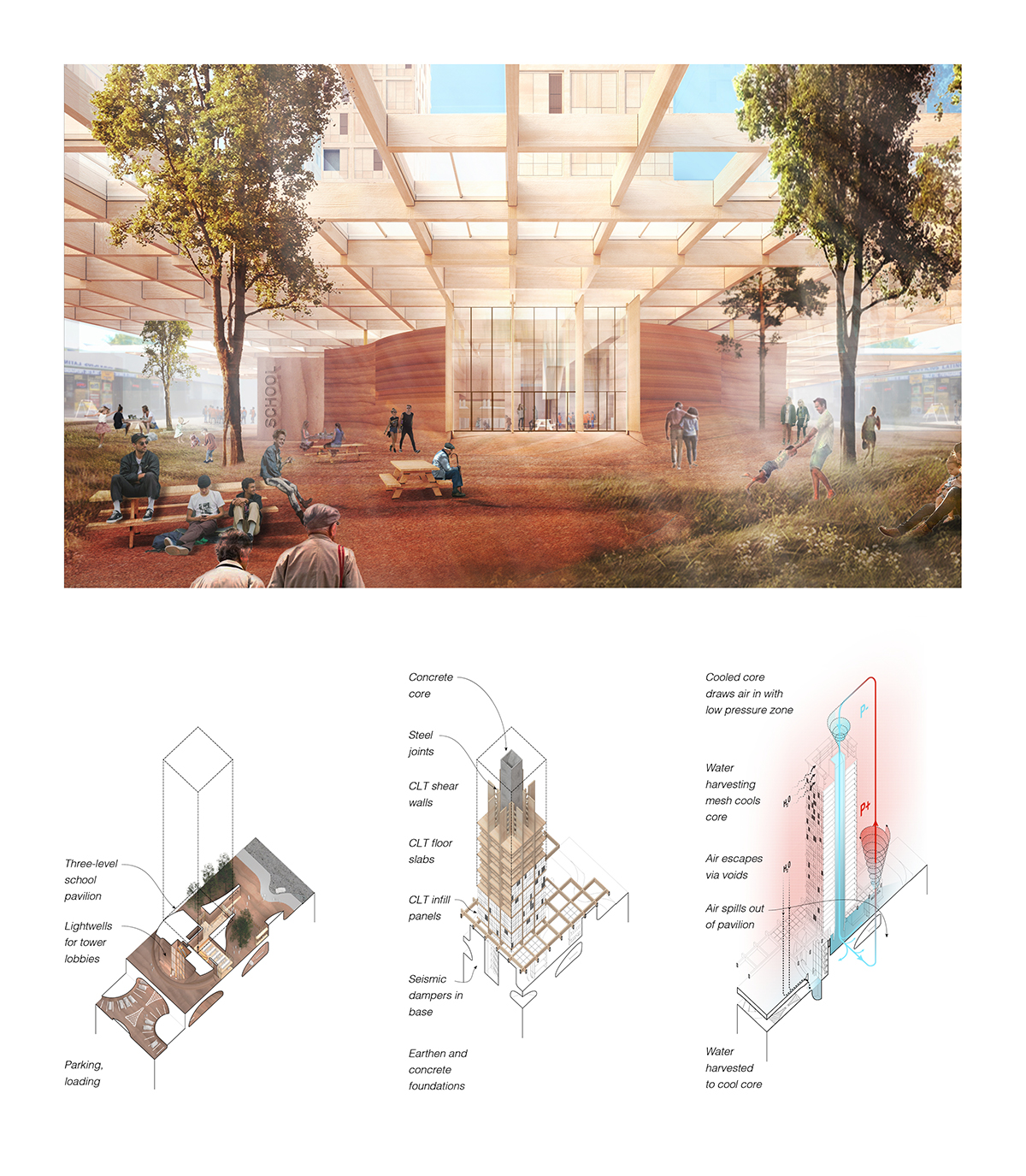

Carbon Park, LA

Augustinas Indrasius (MDes ’19), Peteris Lazovskis (MArch I ’20), and Thomas Schaperkotter (MArch I ’20)

Carbon Park, LA reimagines how real estate investment may fuel social benefit and ecological sustainability by connecting private investment with public space to seek balance for investors, the downtown Los Angeles community, and California’s growing carbon economy.

Metro Strand: Renewed Vitality for Overtown in an Urbanizing Miami

Sam Adkisson (MAUD ’19) and Hiroki Kawashima (MAUD ’19)

Metro Strand: Renewed Vitality for Overtown in an Urbanizing Miami proposes a smarter way for Miami’s continued urbanization, with the added complexity of climate change, to establish a better method for future inner-city growth for the impoverished community of Overtown.

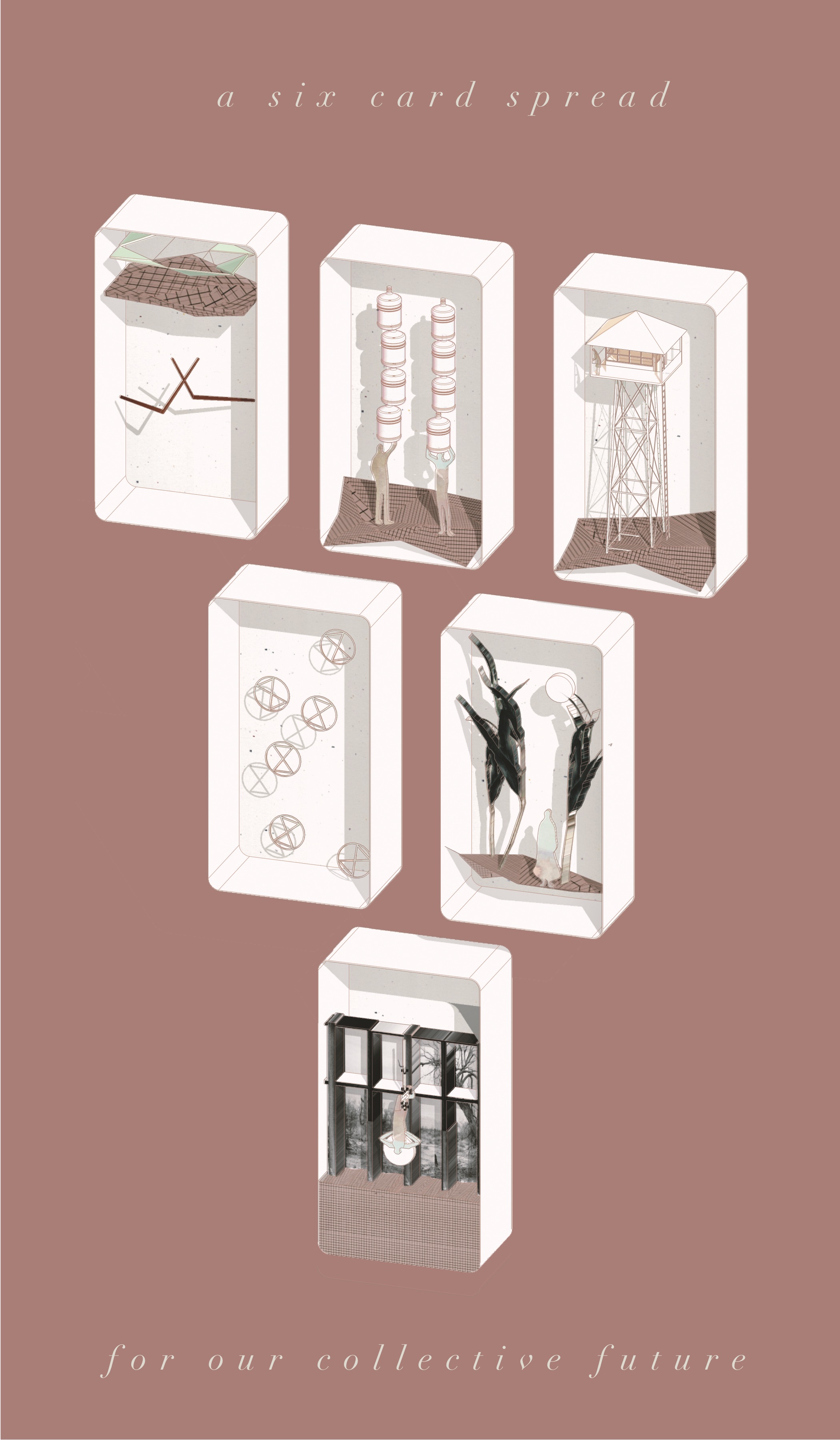

The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic: an Adaption with Projections on a New Climate

Tessa Crespo (MDes ’20)

As an experimental infrastructure, I reimagined the classic archetypes of tarot as a means to reconstitute the human condition and our perceptions of boundary and territory. This required a reexamination of our understanding of being as well as challenging the constructed myths of scarcity and abundance that justify violence towards both human and non-human entities in modern societies. For this project, I reinterpreted a six card spread for our collective climate, where we can look to tarot not as a fortune telling device, but rather a conduit between unconsciousness and consciousness. I believe that alternative modes of representation could empower the disenfranchised and lead towards new forms of legitimacy. Acknowledging that neither frameworks nor facts are static, but rather are continuously being reconstituted, may lead to a form of representation that is more event based than object based. Understanding symbols, such as the border wall, as a phenomenon instead of an object will help us think outside of the constraints of geographic space to speculate on alternative realities or ways of seeing. Experiences constitute our understanding of the world, yet many of the hard sciences avoid the experiential as a legitimate form of knowledge. For this project, I was interested in the idea of tarot as an alternative technocratic device that subverts orthodox projection methods and how a more empathic form of representation could make visible the links between climate change, resource scarcity, and migration.The Hidden Room Elevation

Diandra Rendradjaja (MArch I ’22)

The elevation of this architecture conceals not only the dynamic sectional quality of the interior but also the perceptual discrepancies created through forced perspective manipulation that produces a defamiliarization through scale. Throughout the project, perceptual scale distortion happens mostly in interior framed views while the facade remains static and mute. This representational experimentation investigates the elevation drawing as an instrument to reverse this reading of perceptual scale distortion from an interior depth in the longitudinal orientation to an elevational depth in the transversal orientation.

Taking the elevation of the “normal” room as the stable and ideal scale and projecting it to the other altered rooms produces a new set of elevation that begins to reveal depth as some room appears larger or smaller than the others. This is then re-interpreted as a new form of architecture where each room is an independent volume that intersects three-dimensionally with one another. In contrast with the original architecture, the new architecture expands to a thicker form towards the transversal direction that disrupts the single longitudinal reading of the existing.

Common Shallows

Samuel Gilbert (MLA I ’20), Shira Grosman (MLA I ’20), and Yujue Wang (MLA I ’20)

“Common Shallows” transforms the area of the South Bay into a new type of public space that embraces the shallowness of water as a means of connecting communities and bringing populations together.

The history of Boston can be interpreted through a series of population introductions, land reclamation projects, and ecological degradation. In this project, we are looking at how these three factors have been intertwined for at least 300 years. Specifically, we looked at the trajectory of the African-American population, the Irish population, and the disappearance of shallow water ecotopes in Boston Harbor. We have tracked the migrations, settlements, and displacements of these populations against the steady infill efforts and land reclamation projects in Boston. By tracing these processes in parallel, we have revealed the South Bay as a central knuckle, physically separating these communities.

We divide our site into 7 reserves. The whole is bounded by infrastructures, sea level rise and lack of residential. Since there is a mixture of many public agencies, like MBTA, and some private properties, it’s easier to extend the site into a public entity. Within the site, different reserves are bounded by infrastructures and material conditions. The reserves are defined by the existing material conditions, deconstructed into gravel, substrate and boulders. The surrounding waterfront area will be affected and activated, creating a new coastal edge. The reserves consist of a multitude of shallow water bodies with a new edge, shifting disparate community centers toward one another in a common direction. We have compiled the Shallow Water Anthology (book) to demonstrate the range of conditions and experiences provided for throughout the reserves. Dynamic nature of the tidal range creates a multitude of opportunities for different experiences. The Anthology chronicles the moments of shallowness throughout the day and as conditions change over the next 100 years. Reframing neighborhoods connection to SLR and in so doing, establishing new connections between populations. Shallow water as accessible form of interaction with the ocean