Jump Cut School

Fiona Riley (MArch I ’22)

Jump Cut, the third project of the CORE 1 studio, poses the challenge of creating one building from two apparently disparate sections. Sean Canty’s studio approached this problem by imagining first two plans of two distinct modernist typologies for each of the sections, and then their potential union.

This project relates the two sections by projecting their respective grids to meet one another in an arc that defines the envelope of the building. The center of the arc becomes the primary circulation core, while the swept grid lines become secondary circulation paths that progress through the stepped rooms and connect the two plans.

The paths of these secondary stair corridors are coded by the smaller voids on the facade, switching from singly-loaded to doubly loaded as they pass through each void. This breaks up the building, programmatically a school, into smaller office spaces, mid-sized classrooms, and large gathering spaces, while the voids serve as smaller social areas. Larger, vertical voids provide space for primary, continuous circulation, and bring light deep into the building.

Horizontal Tower for Harvard

Bijan Thornycroft (MArch I ’19)

The tower results from infinite expansion within accepted control; a compromise invented in America as the setback. Setbacks allow for the ground to take over instead of the building. Land abounds while the building stretches out. To stretch in the horizontal direction means for the building to become a line, in plan, as opposed to a point. The building now divides instead of towers. To one side, a park; to the other, a plaza. Two for one. A learning center is the offering of choice by extreme separation, and thereby through extreme categorization. When selecting a place to learn, the choice is between a room of 100 people, 20, or one. Small, medium, large.

What Is This Book?

Inés Benítez Gómez (MDes ADPD ’19), Mariel Collard Arias (MLA, MDes RR ’19), Nicolás Delgado Álcega (MArch II ’20)

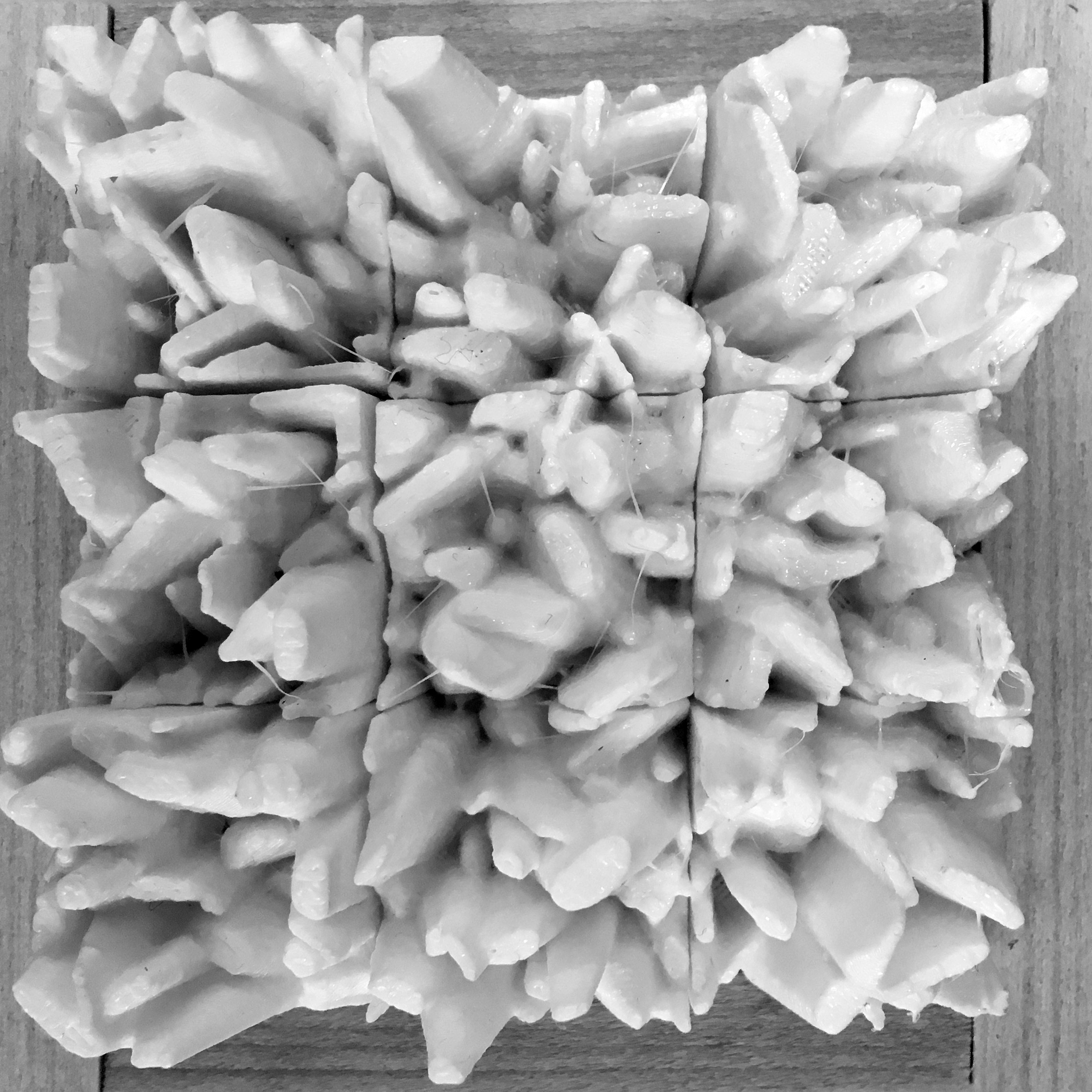

These boxes and book are the outcome of a semester-long search at the Arnold Arboretum focused on the complexities behind research on the field and the development of its corresponding methodologies.

The boxes are the documents that evidence our process: a non-linear path where experiences, ideas, questions, methods and answers emerge seemingly out of order; concurrently through a process of back and forth. Rather than organize the documents as one would in an archive, they are here more so arranged like one would a journal. The aim has been to collect our work in such a way that it allows us to constantly question the way we truly arrived to conclusions; not chronologically; not through the application of standardized procedures independent of the questions, where each new step implies blindly committing to its antecedent ones. The book is our attempt to elucidate our work to others; to bring it into the field of knowledge exchange in a format that effectively translates what has been rich about our process.

The book is organized in time and yet not in a true chronology; it represents relevant references, encounters and exercises, if not in their entirety, at least one to one; actual scale; just like we tried to approach the American Holly specimen that worked with us during the final stretch. It seeks to communicate the value of working on the field; with specimens rather than categories, paying attention to what can be perceived and understood then and there, before resorting to cameras, microscopes or model spaces…

Soil as Resource

Kuzina Cheng (MLA I ’19)

While current uses of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and mechanical tillage may momentarily increase crop yields, it depletes the life-giving components of the soil; thus, diminishing its fertility transforming a vital resource, the soil, into a mere substrate. These agricultural practices along with deforestation have highly degraded the soils of San Martin Lachila and as a community who relies heavily on their crops for self-sustenance, the need for better soil management within the community is even more crucial. Through the implementation of three simple strategies – erosion control, soil amendments, and rotation – an improved agricultural system will begin to rebuild, regenerate and conserve the soil of San Martin Lachila.

Looking at the currently eroded hillsides, a new agricultural system that integrates a process of amending soils will begin to instill soil stewardship as well as provide a new hillside landscape for the community to enjoy. The site becomes a testing ground for the following parameters: the performance benefits of a terraced landscape for erosion control, soil regeneration and the use of windbreaks as linear corridors to begin to reestablish the once forested hillside of Cabo de Hacha. With plots specifically dedicated to producing soil and using plants as indicators of different soil qualities, this new agricultural system uses organic maintenance methods to sustain soil biology all the while allowing both the community and visitors to experience and learn about soil in a more tangible and direct way.

Diffusive Geometries: Vapor as a Tectonic Element to Sculpt Microclimates in Architectural Space

Honghao Deng (MDes Tech ’18)

Tornado beam geometry at various fan speed and boundary conditions

rotating focused beam basic construction mechanism

Testing vapor in physical model with different wall types

Using “Tornado beams” for public spaces

Return to Pleasant Island: A study of Nauru Island

Alysoun Wright (MUP/MLA I AP ’21)

Extraction Through Time: Model as Change

Following the discovery of phosphate, over 80% of Nauru Island was strip mined. The resulting landscape is highly degraded and inhospitable.

Extraction Landscape: Model as Force

The extreme slope of the terrain makes plant succession difficult. Due to a lack of vegetative cover, surface water runoff further erodes the landscape and is polluted with high concentrations of dissolved minerals left behind from extraction.

Phosphate + Limestone: Model as Matter

Composite positive and negative model depicting the extracted phosphate and the remaining limestone pinnacle field.

Limestone Pinnacles: Model as Matter

Following phosphate extraction, a jagged field of limestone pinnacles, or a karst, forms a new inhospitable terrain.

Pinnacle Field: Model as Matter

The limestone pinnacle fields form microsites. The slope and aspect of this landscape are extreme, resulting in slow successional growth.

Plant Succession: Model as Change

Over time, the landscape has undergone a slow process of successional growth, and the pinnacle fields have begun to infill with vegetation, soil, and sediment.

How Women’s Movements Can Get New Protocols?: A Kit for Future Revindications

Danela Terán (MDE ’20) and Carolina Sepúlveda (MDes ’20)

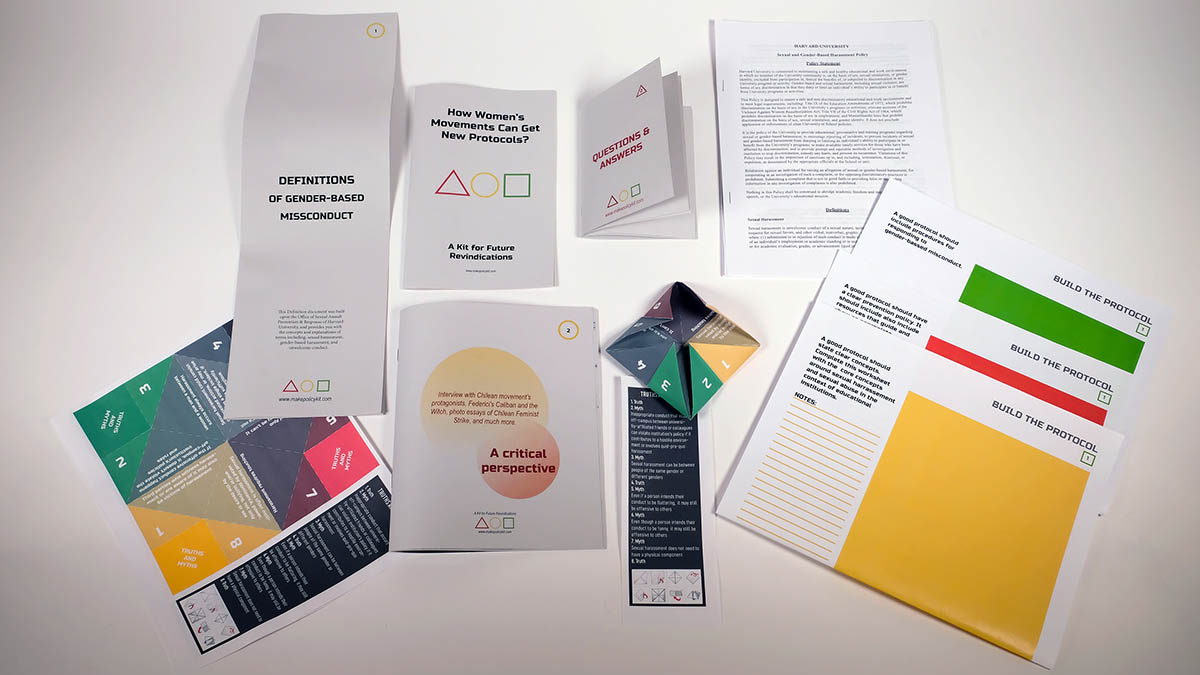

In 2018 there was a wave of feminist demonstrations in several countries and contexts that denounced violence and sexual harassment towards women, such as the #MeToo movement in the US and the #NiUnaMenos movement in Latin America. This wave not only exposed the ubiquity of gender violence but also questioned the educational institutions protocols that protect women from sexual violence and harassment.

The project is an object-kit that provides tools to start a conversation about sexual harassment, gender-based discrimination and protocols. This object is aimed at women movements within educational institutions to learn how a protocol on sexual violence and harassment in schools and universities should be built. Based on Chilean Universities and Harvard’s efforts, successes and obstacles, the kit will propose simple ways to recreate safe spaces of conversation and exchange to get clear petitions that can later become protocols, policies or laws.

This kit can be used by communities that haven’t started a conversation about sexual harassment protocols, but also be useful to contexts like the US, where there are clear policies and a federal law, Title IX, but female students organizations still need a more easy, interactive and compelling way to talk about these issues.

The purpose is not only to educate a community on the subject but also to provide tools that will allow policy building to be an easy and straight forward matter, as policy building needs to be followed by a process of negotiation and approval and then followed by a process of teaching and promoting the new protocol.

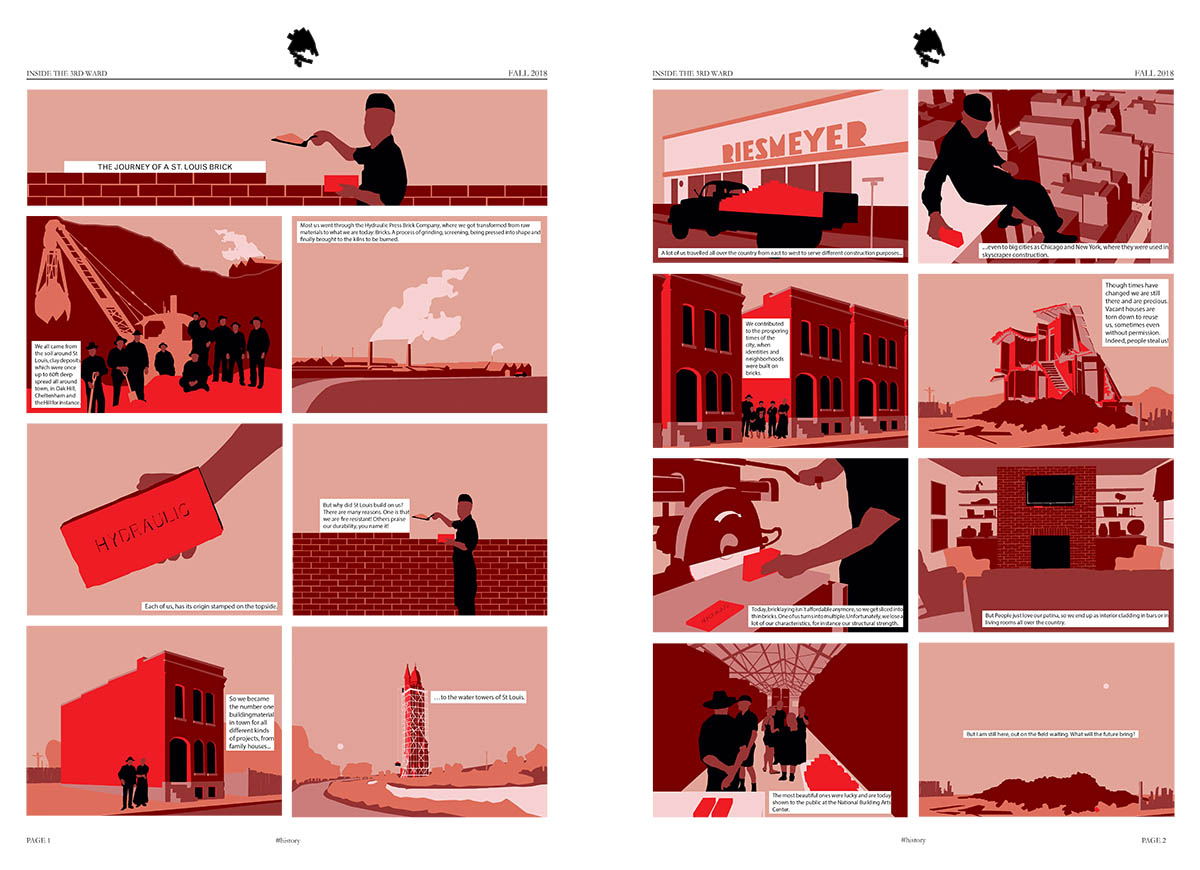

STL Brick Bank

Jakob Junghanss (ETH Zurich Exchange Program)

In the last decades, St. Louis’ built legacy has been increasingly challenged by rising vacancies. This has shaped many neighborhoods’ appearances, including the Third Ward. Demolition and material salvage emerged as strategies to address this issue, while providing job opportunities for local citizens. But how do these markets operate and what happens to the materials, such as the famous St. Louis bricks?

Today, salvaged bricks leave the neighborhood with the demolition companies, entering a booming market of reclaimed materials all over the country. St. Louis bricks are a popular reclaimed good; currently two bricks are being traded for one dollar. Considering that a vacant house can be bought for $1,000, built out of approximately 40,000 bricks, it seems that the material value of a disassembled house is more than that of an intact one.

This project wants to emphasize that the neighborhood should contribute and benefit from the material flows and their revenues. Otherwise the community is not just losing the bricks as an essential part of their built heritage, but also not profiting from the reclaimed brick business.

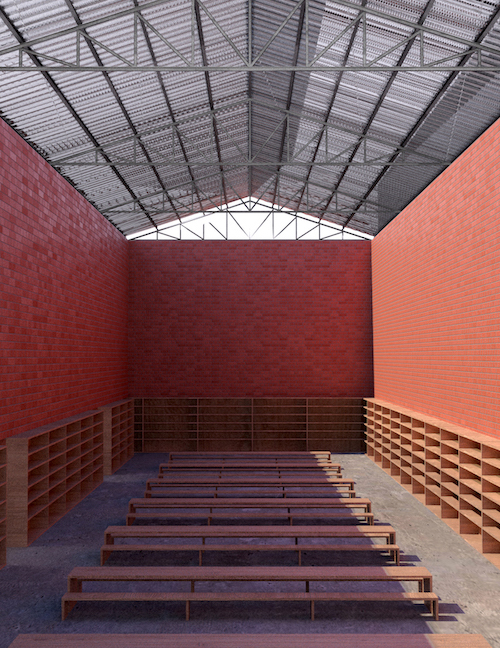

The proposal–a cooperative brick bank for the Third Ward–transforms salvaged bricks into an asset for the community. Storing bricks locally enables the community to invest into the salvaged material market, as well as ensuring that the bricks and their history are staying in the Ward. A loose storage–the checking account–provides brick traders on a daily basis, while a solid masonry structure–the savings account (also defining the brick banks appearance)–offers a long term asset. The brick bank is anchored in the neighborhood, offering proximate institutions a space to activate and engage with the neighborhood. Depending on the salvage brick market, the appearance of the brick bank is constantly evolving.

A Monastery in Framingham

Nicolás Delgado Álcega (MArch II ’20)

Set in 2048, the monastery is a home base for the pursuit of meaning. It is one more world amidst a context, not a model. It is a proud position, not a retreat.

The monastery is built upon the physical remains of yet another world. It produces a new future for the existing urban objects on the Framingham site in an anciently fresh way.

The monastery is built by quarrying material within the city. A resource is understood as a material we invent a use for because we know it. The monastery is built from the remains of a highway intersection being demolished nearby. Principally, concrete rubble and granite curbs. There is more thinking and less toiling. Little is wasted. A new kind of craft emerges.

The common Bath is a fundamental component of life in the monastery. It is communal, and yet deeply about the self and body. The spaces in the Bath are sequential but open; available for a couple of minutes with one’s mind elsewhere, or for much longer than that, immersed in sense perception and feeling.

The Bath is not hermetic. It lets lights travel into the spaces; it accepts the entry of unexpected sounds; it reverberates certain movements from the exterior, sometimes. It is a deeply internal space that nonetheless makes one aware of the forces of that which we call the ‘exterior’; what we only understand as shadows in the walls of the cave because they exist outside of the ‘world’ we have built.

Halftone Blur

Estelle Yoon (MArch I ’20)

The project attempts to translate the depth of a 3D form in a digital environment into a graphic code that is mapped onto the form itself. The extra layer of graphic alters the perception of the form – the z-depth information turns into halftone and registers an uninterrupted graphic from a favored elevational view, or the “front” of the object. When turned around, the dots start to stretch and morph into something entirely different than the implications of the original graphic, in a way that responds to the angle and depth of the lateral surfaces it sits on but also unexpectedly in the misalignments of the graphic and the volume. The unconsidered sides, or the “back,” starts to reveal the assembly logic of the form and its thinness. The formal aspiration lies in colliding volumetric aggregate in various orientations with a rigid cubic surface – setting up a relationship between object and frame, favored view vs others. The process learns its method of applying imagery on volume from hydro-dripping.