What Oysters Can Teach about Life in the Climate Crisis

On the southern coast of Taiwan, groundwater pumped from the earth flows through dense tangles of pipes to supply industrial-scale fish farms. This intensive aquaculture has had a dramatic effect on the surrounding land of Pingtung County. Daniel Fernández Pascual, winner of the 2020 Wheelwright Prize, noted that the pumping of groundwater has caused some areas to sink 6 to 8 centimeters each year. Speaking at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in March, Fernández Pascual described how “buildings keep losing their ground floors. Living rooms become garages. Doors become stairs. Roofs touch the street.”

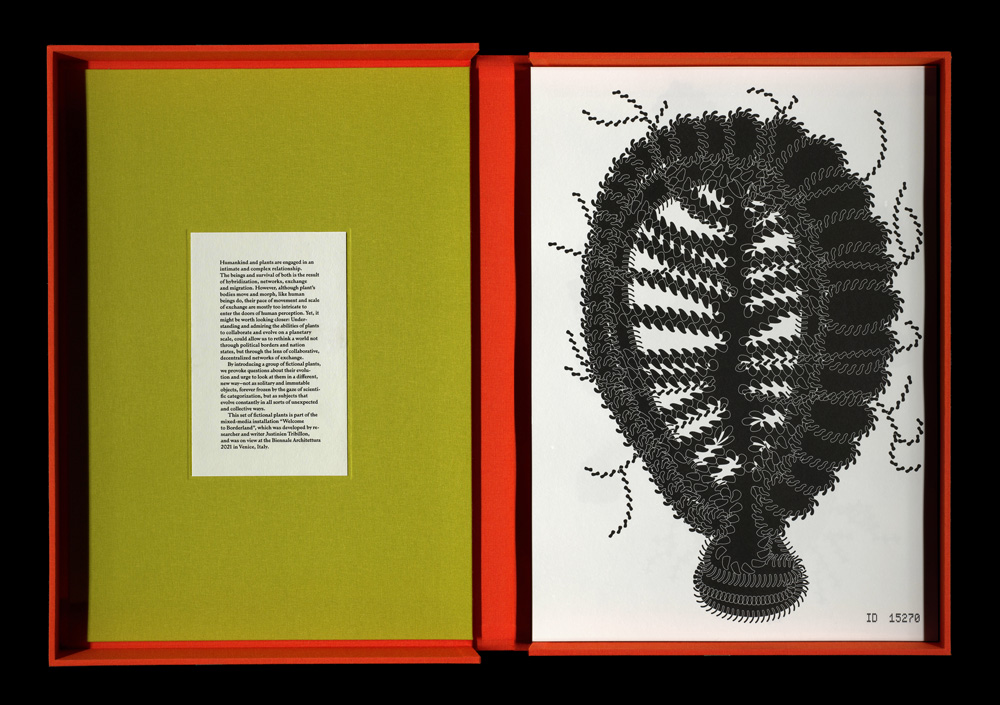

Taiwan’s fish farms exemplify the “extractivist” logic of aquaculture—and its long-term consequences. Pingtung County is one of the areas that Fernández Pascual studied during his Wheelwright term, which brought him in contact with coastal communities in ten countries, from the Isle of Skye in Scotland to the shores of Chile to coastal towns in China. The $100,000 award enabled him to take a global perspective on the risks of intensive aquaculture while identifying alternatives that could become the basis for a sustainable future. Resisting extractivism, Fernández Pascual aimed to foster a “tidal commons,” which he defined as a “framework of shared assets and shared stewardship of ecological structures in the planet’s shoreline.”

The title of Fernández Pascual’s talk, “Being Shellfish: Architectures of Intertidal Cohabitation,” reflects the central place of oysters, mussels, scallops, and other bivalves within his vision for the tidal commons. “Oysters filter the sea,” he said, “and in so doing their shells record histories of coastal habitation as material witnesses of the Anthropocene.” The natural habitats of these creatures comprise the same coastal regions that fish farms can spoil. “Bivalves and other foods have been a tool for us to understand the impact of intensive food production,” Fernández Pascual said, “while also supporting the different struggles and solidarity networks across communities in the ruins of extractivism.”

The scope of Fernández Pascual’s research extends far beyond encouraging the consumption of more ethical seafood—though bivalves are indeed tasty, sustainable alternatives to farmed fish. At the GSD, he put forward a holistic vision for new models of economic development and strategies for navigating a changing climate. In addition to rethinking food supply chains, bolstering restaurant menus, and undertaking educational initiatives, “intertidal cohabitation” means harvesting resources, such as shells and seaweed, that have long been used in traditional building practices and imagining new uses for them in the present.

Fernández Pascual may be best known for his collaborations with Alon Schwabe as Cooking Sections. Their work, often featured in international biennials, includes performative meals that foreground urgent ecological questions. CLIMAVORE, one of their research initiatives, aims to “transition to alternative forms of nourishment in the climate crisis.” In 2017, ATLAS Arts, a cultural organization based in Skye, Raasay, and Lochalsh in northwest Scotland, invited Cooking Sections to the area, where salmon farming dominates the local economy. Fernández Pascual and Schwabe developed a project that eventually became a long-term engagement with the community. One aspect of their work is an installation constructed from metal oyster cages. Built in an intertidal zone, the structure is submerged at high tide and inhabited by bivalves. At low tide, it becomes a communal table for the performative meals that Cooking Sections organizes as well as a public forum for discussions and workshops.

One fundamental question raised at these forums is how the economies of Skye, Rassay, and Lochalsh might transition away from fish farming. Enhancing the role of bivalves in the food supply chain is part of the answer. At the GSD Fernández Pascual also highlighted potential uses of oyster shells as building materials. He has been collaborating with a team to create tiles from oyster shells that have been cleaned, ground up and processed. A pair of murals depicting bivalves that he and Schwabe created demonstrate the potential of this material. They employed similar techniques for Oystering Room (2020), their contribution to the 2020 Taipei Biennial. Visitors to the installation could recline in lounge chairs crafted in a material inspired by a Taiwanese technique of mixing oyster shells, glutinous rice, and maltose sugar to create a binding paste. Visitors could also sample an exfoliating skincare product derived from oyster shells—a luxurious demonstration of how bivalve cultivation could counter the sinking economics of fish farming.

Oyster shells have long served as a source of fertilizer and as a key component of tabby concrete. Fernández Pascual surveyed building traditions in Southern China, where oyster shells are employed directly as siding, as well as in Japan, where walls made of oyster-derived plaster keep interiors well ventilated. Seaweed harvested from intertidal zones has also served as roofing material in Denmark, China, and elsewhere. In revisiting these traditions Fernández Pascual was not attempting to recover a lost pastoral ideal. The goal is “cohabitation” in the present, a concept that challenges us to “learn how to produce an ecological future that enables us to live well beside toxicity and unstable, shifting seasons.”

In gathering information from around the world, Fernández Pascual also facilitated a global exchange of information about what learning to live beside toxicity might mean. “Research conducted as part of the Wheelwright Prize has tied together different experiences from communities dealing with pollution from intensive farming,” he said, emphasizing how these communities were interested in “sharing lessons on collective usership of the coast and architectures of intertidal stewardship and resistance.” While the Wheelwright Prize supports such an international outlook, Fernández Pascual’s award was announced just as the world shut down due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Speaking about his research process prior to his public talk, Fernández Pascual noted the importance of local collaborators, many of whom he contacted remotely. “Especially when we’re talking about extractivism,” he said, it’s vital to ensure that you “don’t become extractive in the research.” The ethics of working as “the outsider coming to learn,” especially during the pandemic, were at the forefront of Fernández Pascual’s process.

The pandemic also altered the focal point of the project. Initially, Fernández Pascual and Schwabe envisioned restoring a building on Skye that could serve as a permanent hub for their Climavore work. Yet with rural real estate in high demand, the project fell through. This shift proved fortuitous, however, allowing the project to take the form of an “assemblage of formats” that span different practices and fields of knowledge while engaging a wider range of stakeholders, from educators to activist groups to chefs. “Precisely because we did not have to take care of a building,” he said, “we could rethink allyship and make the project much more open and diverse.”

This fluid approach also forced Fernández Pascual to take an expansive view of his own role as a designer, researcher, artist, and activist. He described learning “how to jump boundaries across disciplines, especially when talking or thinking about the food supply chain.” His research incorporates vernacular techniques and technological innovation in material projection. “There are many networks of knowledge involved in figuring out what it means to live besides toxicity and to imagine an alternative scenario,” he said, encouraging design students in particular to look beyond their disciplines to “find the necessary allies to join in the quest for alternatives.”

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Julie Bargmann (MLA ’87), and Stella Betts (MArch ’94) among American Academy of Arts and Letters 2024 Architecture Award Winners

The American Academy of Arts and Letters recently announced the winners of its 2024 Awards in Architecture , an annual awards program totaling $60,000 in prizes that honor established and emerging architects. Krzysztof Wodiczko, Professor in Residence of Art, Design and the Public Domain, Emeritus, at the GSD, Julie Bargmann (MLA ’87), and Stella Betts (MArch ’94) of the firm LevenBetts are among the recipients this year of a $10,000 award.

According to a statement released by the Academy, Krzysztof Wodiczko is being honored as a visual artist who explores “ideas in architecture through any medium of expression.” Known for creating large-scale slide and video projections in both gallery and civic settings, Wodiczko has produced more than 90 projects around the world since 1980. The installations often feature politically charged images and texts projected onto architectural facades and monuments, creating startling juxtapositions that prompt critical reflections on historical trauma and the power dynamics embedded in public space. Through his art, Wodiczko has engaged with immigrants, war survivors, domestic abuse victims, and homeless veterans.

Wodiczko has created projections on the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC (1988/2018); the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1989); Kraków’s City Hall Tower (1996); Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument (1998); Kunstmuseum Basel (2005); the Goethe-Schiller Monument, Weimar, Germany (2016); and the Admiral Farragut Monument in Madison Square Park, New York (2020). In 2021, the GSD exhibited the career-spanning Interrogative Design: Selected Works of Krzysztof Wodiczko at Druker Design Gallery. Coinciding with the retrospective, Harvard Art Museums presented the video-projection installation Krzysztof Wodiczko: Portrait .

Julie Bargmann (MLA ’87) is a landscape architect, founder of D.I.R.T. Studio (Dump It Right There), and Professor Emerita of Landscape Architecture at the University of Virginia. Her design practice rehabilitates contaminated and postindustrial sites, transforming neglected and abandoned lands into functional sites. Bargmann won the first Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize in 2021 for her dedication to addressing social and environmental justice through building regenerative landscapes.

Stella Betts (MArch ’94) is co-founder and principal of LevenBetts. She is currently a senior critic at Yale University’s School of Architecture. In 2020, Betts was awarded the New Generation Leader by Architectural Record’s Women in Architecture Annual Award. The Academy’s press release notes that Bargmann and LevenBetts are representative of “American architects whose work is characterized by a strong personal direction.”

The Academy’s architecture awards program began in 1955 with the inauguration of the Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize and has since expanded to include four Arts and Letters Awards. This year’s recipients were chosen from a group of individuals and practices nominated by the members of Arts and Letters. The members of 2024 selection committee include the GSD’s Toshiko Mori (chair), Robert P. Hubbard Professor in the Practice of Architecture, and Marlon Blackwell, Robert P. John Portman Design Critic in Architecture. The committee also included Deborah Berke, Merrill Elam, Steven Holl, Michael Maltzan (MArch ’88), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Billie Tsien.

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is an honor society of the country’s 300 leading architects, artists, composers, and writers. Each year it elects new members as vacancies occur, administers over 70 awards and prizes, exhibits art and manuscripts, funds performances of new works of musical theater, and purchases artwork for donation to museums across the United States. James Carpenter (LF ’90) will be inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters award ceremony in May. Carpenter is one of 19 new members and four honorary members that will be honored.

Holly Samuelson Awarded Starter Grant Funding from the National Science Foundation

Holly Samuelson, Associate Professor of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, is part of a multidisciplinary team that has been awarded a major grant by the United States National Science Foundation (NSF). The team’s project, titled “Intelligent Nature-inspired Olfactory Sensors Engineered to Sniff (iNOSES),” addresses the urgent need to “acquire real-time information about the air we breathe,” according to their proposal. The portable chemical gas sensor they are developing relies on artificial intelligence (AI) to accurately identify volatile compounds in the air.

Samuelson is a Co-Principal Investigator alongside Alexander Tropsha, Professor of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Principal Investigator is Joanna Aizenberg, Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Material Sciences at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and associate faculty at Harvard’s Wyss Institute.

The NSF recently announced investing $10.4 million to “develop innovative technologies and solutions to address a wide range of challenges related to chemical and biological sensing.” The Phase 1 grant that Samuelson’s team received is worth approximately $650,000.

According to the team’s proposal: “The real-time chemical sensing data will pave the way to standardization in detection and reporting across sectors, a documented challenge leading to poor accountability in emission monitoring, inefficiently timed ventilation and air purification processes, and unnecessary food waste, all of which are responsible for immense climate, health, and socio-economic impacts.”

The team is working toward the Phase 2 grant submission, which is focused on bridging basic science and market deployment. Six teams be funded in Phase 2 for up to $5,000,000 each.

The grant is part of the NSF “Convergence Accelerator Track” program. According to an NSF press release, the program “builds upon a wealth of foundational knowledge and recent advances in chemical sensing, sensor technology, robotics, biomanufacturing, computational modeling and olfaction to address challenges related to environmental quality, industrial agriculture, food safety, disease detection and diagnostics, personal care, substance use or misuse and possible adversarial threats.”

The NSF is an independent federal agency that supports science and engineering in all 50 states and US territories. Established in 1950 by Congress, the agency’s investments account for 25 percent of federal support to America’s colleges and universities for basic research.

Lindsey Krug (MArch ’19) and Lukas Pauer (MAUD ’14) Awarded 2024 Architectural Education Awards

The Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) and the American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS) recently announced the recipients of the 2024 Architectural Education Awards, which honor architectural educators for exemplary work in areas such as building design, community collaborations, scholarship, and service. According to the ACSA/AIAS press release, the “award-winning professors inspire and challenge students, contribute to the profession’s knowledge base, and extend their work beyond the borders of academia into practice and the public sector.”

Lindsey Krug (MArch ’19) and Lukas Pauer (MAUD ’14) received the New Faculty Teaching Award, a category that “recognizes demonstrated excellence and innovation in teaching performance during the formative years of an architectural teaching career.”

Lindsey Krug is Assistant Professor in Architecture at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Through the lens of the architectural user as a body in space, her work focuses on how design solidifies and reinforces taboos, hierarchies, and inequities. Krug has contributed to spatial research investigating human rights abuses and the killing of protesters in the 2014 Euromaidan protests in Ukraine as well as the ongoing and projected climate risks of melting permafrost in Russia. Her project “Gendered Generic” explores the relationship between gender, typology, and architecture. Most recently, her project “Women Offer You Things,” a study of print magazines, gender, and semiotics of the countryside, was exhibited at the Guggenheim in New York as part of the exhibition Countryside, The Future curated by OMA/AMO. Krug has previously practiced at WOJR, SITU Research, ODA, and Studio Gang.

Lukas Pauer is Assistant Professor of Architecture and Emerging Architecture Fellow at the University of Toronto. There, his contribution at disciplinary intersections is reflected in his engagements as a Faculty Affiliate in Urban Studies at the School of Cities as well as a Faculty Affiliate in Global Affairs and Public Policy at the Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies in the Munk School. Pauer is Founding Director of the Vertical Geopolitics Lab, an investigative practice and think-tank at the intersections of architecture, geography, politology, and media, dedicated to exposing intangible systems and hidden agendas within the built environment. He has been selected as an Ambassadorial Scholar by the Rotary Foundation, a Global Shaper by the World Economic Forum, and an Emerging Leader by the European Forum Alpbach—leadership programs committed to change-making impact within local communities. Pauer has gained extensive technical experience in construction at firms including Herzog & de Meuron and LCLA Office.

Founded in 1912 by 10 charter members, ACSA is an international association of architecture schools preparing future architects, designers, and change agents. The organization’s membership includes all of the accredited professional degree programs in the United States and Canada, as well as international schools and two-year and four-year programs. Together ACSA schools represent some 7,000 faculty educating more than 40,000 students. The AIAS is a nonprofit, student-run organization dedicated to programs, information, and resources on issues critical to architecture and the experience of architectural education.

From Drought to Flood: Solutions for Extreme Climate Events in Monterrey, Mexico

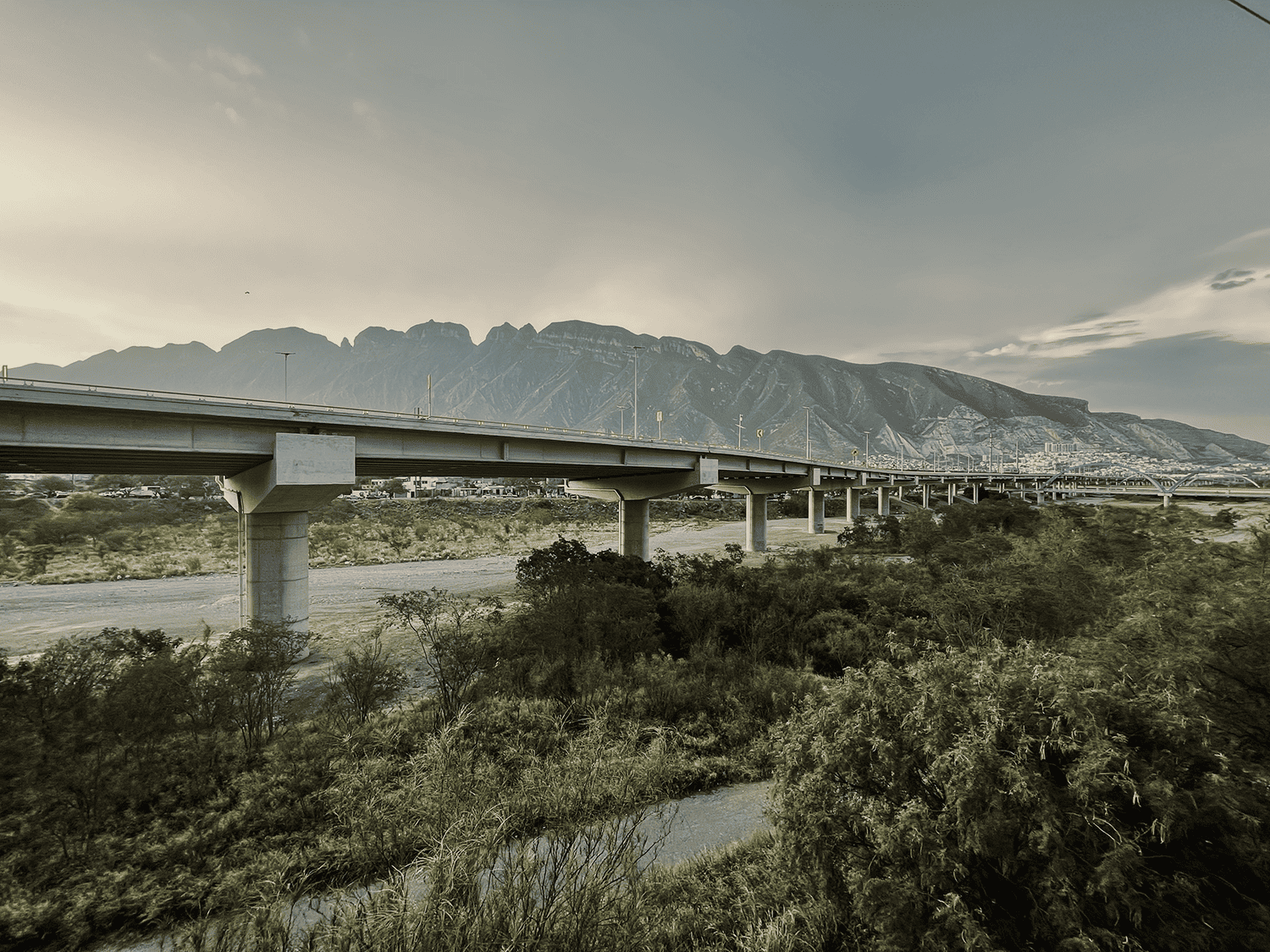

In 2022 and 2023, Monterrey, Mexico’s second largest city, experienced a critical shortage of water and, like Cape Town in 2018, was close to a Day Zero of water provision. The emergency made international headlines , as the state government rationed water for many of the city’s five million residents. While struggling at times to supply water to residents, Monterrey is also well-known for its severe floods that have peaked in intensity during deadly hurricanes, such as Gilbert in 1988 and Alex in 2010. In recent years the fluctuation between these extreme events has been intensified by a changing climate.

Like many other cities, Monterrey is not prepared for a warming planet with increased volumes of water in its atmosphere and extended droughts. The impervious urban ground that covers much of the city is designed to drain water as quickly as possible. Agriculture, industry, and citizens overexploit water unsustainably. As a result, during much of the year the Santa Catarina riverbed remains dry. Yet at times of heavy rain, it is prone to overflowing, with potential catastrophic results.

In the fall 2023 studio “AQUA INCOGNITA: Designing for extreme climate resilience in Monterrey, MX,” GSD Design Critic Lorena Bello Gómez worked with students to devise design strategies along the Santa Catarina watershed to increase water security and to reduce flood risk. Bello was invited to Monterrey after her work on the first iteration of AQUA INCOGNITA, in 2021 and 2022, which focused on the Apan Plains, a region that shares a basin with Mexico City and also struggles with its water supply.

For Bello, every studio is an opportunity to expose students to real-world climatic problems and inspire efforts to restore a lost balance with the water cycle. “Traveling with students for field research and engagement is a fundamental part of the pedagogy,” she explained. “The territorial scale of a project dealing with water risk in an urban region through the lens of an urban river, requires the ability to constantly telescope from macro to micro scales.” According to Bello, digital tools like Google Earth and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) cannot recreate the experience of “inhabiting and crossing the river with your own feet to understand its ecology and scale, and that of its surrounding infrastructures.”

Bello’s focus on the Santa Catarina River watershed developed through a yearlong engagement with the regional conservation institution Terra Habitus , which sponsored the studio. In addition to giving students firsthand experience, Bello’s studio was also an opportunity to help those fighting to change the status quo on the ground. “Deciphering where to insert the needle in this impervious skin is the first incognita to solve,” Bello said. “We know that there is the potential to recover this river as an ecological corridor and climate resilience infrastructure for the city, but we also need to know that there are local academics, organizations, and citizens that could benefit from our work to push the political will.”

Bello’s fieldwork in advance of the studio included meetings with a variety of stakeholders. She gathered input from representatives of community groups and planning agencies as well as political leaders such as Monterrey’s mayor, Donaldo Colosio, and the mayor of neighboring San Pedro Garza García, Miguel Treviño. She also met with Juan Ignacio Barragán, the director of the local water operator Servicios de Agua y Drenaje de Monterrey. Other important preparation included a Spring 2023 research seminar, “Resilience Under New Water Regimes: the case of Monterrey Day-Zero”, supported by PhD candidate Samuel Tabory (PhD ’25).

Daniella Slowik (MLA II ’24) chose to take the studio because she is already focused on climate- and water-related projects and sees herself working on these topics after she graduates. “Different parts of the world are going to continue to experience massive extremes,” she said, “and we have to learn how to work within those constraints in our design field.”

Students toured the riverbed with two local conservation groups as soon as they landed in Monterrey. They examined the soil and plant life in a dry section of riverbed running along one of Monterrey’s major highways before visiting Los Pinos, an informal settlement along the river. Locals shared memories of playing soccer, riding motorbikes, or attending parties on the riverbed, but they also expressed their new understanding of the river as a unique healthy ecology in otherwise desertifying Monterrey. The value of being on the ground, as Bello said, was in “sensing citizens’ empathy towards its river when they walk with us, learning about agricultural practices in the mountains, or understanding from local experts on policy and cultural challenges to overcome.” She continued, “This physical and personal exchange propels students’ imaginations, while their questions make locals aware of hidden aspects that they were overseeing.”

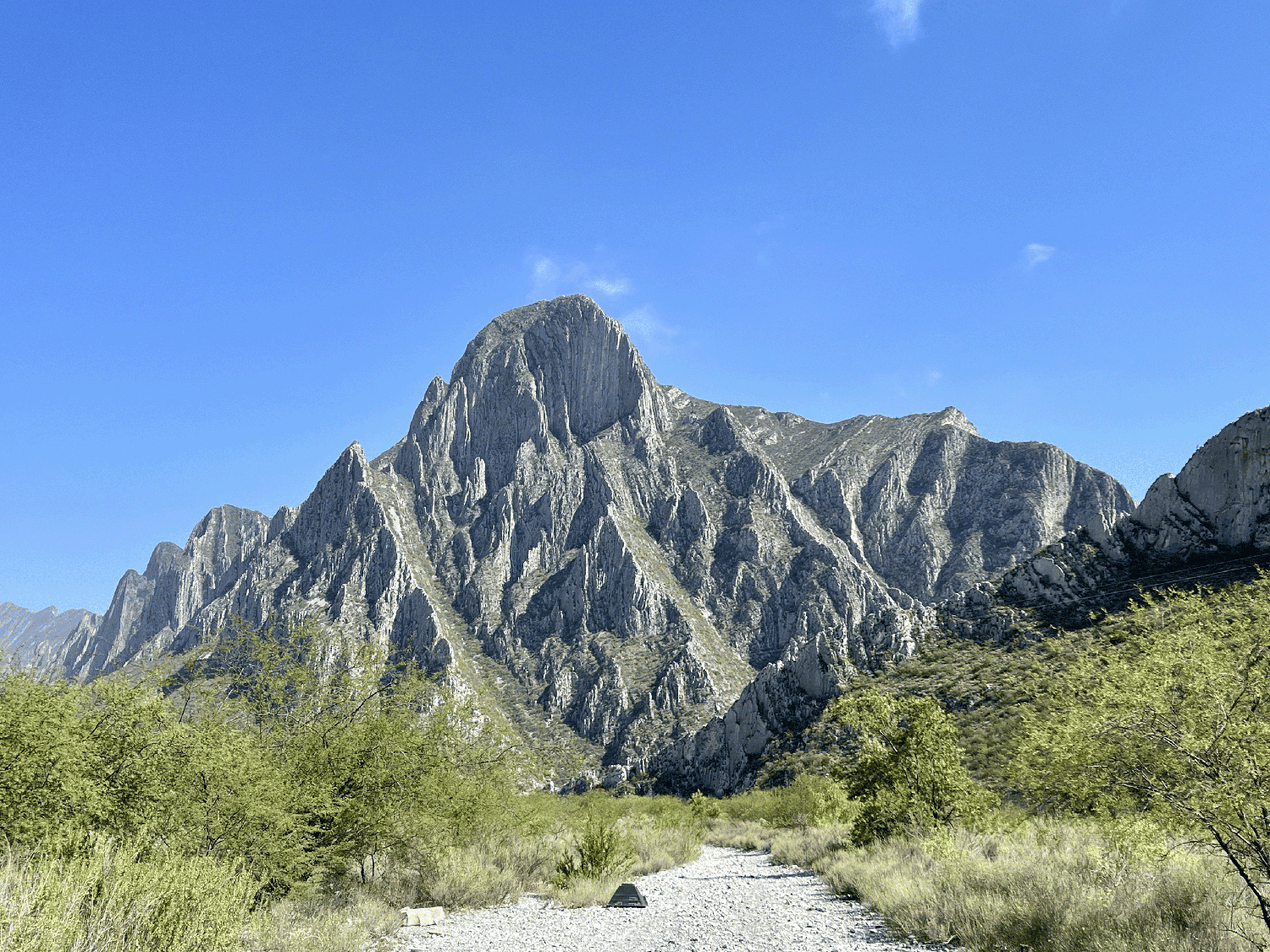

The group later drove to La Huasteca, the first canyon in the Parque Cumbres National Park in the nearby mountains that is the source of the Santa Catarina. The area has also become a site of unregulated settlements despite its protected status. “Traversing the lengthy river,” Bello explained, allowed students to “understand the duality between its urban condition downstream—today a flood-control channel—and its powerful upstream condition along the monumental Huasteca and Cumbres National Park, or by its flood control dam Rompepicos.”

The studio also spent several days participating in the Urban Hydrological Adaptation symposium and workshop sponsored by the Tecnológico de Monterrey with GSD former graduate Ruben Segovia (MArch II ’17). Organized by Bello and Segovia, the gathering of architects, landscape architects, and other academics built on conversations she had at the Tec de Monterrey on her previous fieldwork visits. Over the course of several days, students presented case studies of other cities with rivers that they had prepared earlier in the semester.

Several afternoons were devoted to site visits to locations ranging from parks such as the upscale Paseo San Lucia, an artificial canal offering boat rides, to Centrito, a neighborhood in the process of being rebuilt, where the group navigated several blocks of construction sites in 95-degree heat. A highlight that was both fun and educational was a hike in Chipinque National Park, which offered breathtaking views of the Sierra Madre Oriental and the ability to view the city within the context of the mountain landscape.

Inspired by the knowledge gleaned from the site visits and motivated by meetings with representatives from the municipalities of Monterrey and nearby San Pedro to address urgent needs, students’ final projects displayed a variety of alternative futures for the Santa Catarina River. While working individually, they also tackled collectively the myriad of challenges to overcome at the Rompepicos flood control dam, at the Cumbres National Park, and along the Santa Catarina River from the Cumbres to the urban park Fundidora. The final projects displayed a wide variety of solutions. Some students chose to center their work on the mountainous area around La Huasteca; others took as their focus the highways or parks closer to the urban center. (See an overview of the projects below).

As climate change becomes an unavoidable concern in the design disciplines, the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture has pledged its “abiding commitment to climate mitigation and adaptation through its curriculum, faculty research, and design culture.” Indeed, many students cited the urgency of climate change as a primary reason that they chose this particular studio. Bello’s career has also focused on climate. In addition to her previous research in Mexico, she has used her background in landscape, architecture, and urbanism in her work with environmentally vulnerable communities in India, Colombia, and Armenia. Weather permitting, she says with a smile, she plans to expand the Monterrey studio next fall.

For the final review, students presented their work in a sequence arranged geographically along the river transect, presenting the different challenges and opportunities to overcome by design such as:

Reciprocity at Cumbres National Park

- Jianing Zhou (MLA II ’24)’s project proposes an alternative network of almost invisible “incognito dams” as a counterpoint to mega-projects meant to control flood risk

- Emily Menard (MLA II ’24) explores reciprocal relationships between those who visit and inhabit the park, towards a more mutualistic and regenerative land use for water conservation

The ephemerality of flooding

- Lucas Dobbin (MLA I AP ’24) created “room for the river” at a key bend and point of risk inflection for extreme water flows entering the city from Parque Cumbres

- Pie Chueathue (MLA II ’24) uses the time in between floods to introduce a temporary/light-footprint tree nursery to promote urban tree canopy and work

Vertical and horizontal capillarity

- To reduce flood risk in the larger watershed, Boya Zhou (MLA I AP ’24) proposed starting to recover the network of streams while reconnecting them to the urban fabric

Circularity

- Responding to the near-shoring boom in Monterrey, Sanjana Shiroor (MAUD ’24) explored principles of circularity for brownfields along the river’s corridor to counter low-density sprawl

Bridging and descending to bring the edge of the city to the river

- Ashley Ng (MLA I ’24) designed a promenade

- Sophie Chien (MLA I AP/MUP ’24) proposed an inhabited bridge

- Using bridges as a river entrance to descend to a newly terraformed riverbed, allowing for habitat and inhabitation between storms, was the design vision of Annabel Grunebaum (MLA I ’24), Miguel Lantigua Inoa (MArch II/MLA I AP ’24) and Bernadette McCrann (MLA I AP ’24)

Climate justice

- Daniella Slowik (MLA II ’24)’s project emerged from a deep engagement with the history of Independencia, a marginalized community near the river, and asked what it would mean to convert the river into a community asset rather than just a source of vulnerability and risk

A New Future for a Colonial Fort in Ghana

The village of Ada Foah sits on the coast of Ghana where the Volta River flows into the Atlantic. Its name—a centuries-old vernacular adaptation of “fort”—acknowledges an erstwhile landmark: Fort Kongenstein. Constructed by Danes in the eighteenth century, Fort Kongenstein facilitated trade in goods and, for a period of about a decade, enslaved people. It is one of many such forts erected on the West African coast by European traders and settlers. These foreign structures, often built from materials imported from Europe along proto-globalized trade routes, stand as remnants of the complex and brutal colonial history that has shaped the region.

Though other forts in Ghana, such as Cape Coast Castle, have been preserved and rehabilitated, Fort Kongenstein today is at risk of being forgotten. Its historical significance is belied by its current physical condition. Most of the original stone fort has washed into the ocean, destroyed by the severe coastal erosion that has accelerated in a changing climate. What remains of the site includes a trading post, built in concrete and timber sometime after the British took power in the area, as well as a brick residential structure for the fort’s captain. In recent years, members of the Ada Foah community have taken steps to reclaim the site, adorning its walls with murals and occasionally hosting cultural events in the ruins.

While the fort has fallen into disrepair, tourist facilities and villas have sprung up in the area, catering to those drawn to the area’s natural beauty and seeking respite from the bustling capital Accra, a three-hour drive away. Caught between tourist development and relentless coastal erosion that has only accelerated with climate change, Ada Foah’s namesake has an uncertain future.

Yet this uncertainty also presents opportunities to transform the site into a facility with contemporary meaning. “Forgotten Fort Kongenstein,” an option studio led by Olayinka Dosekun-Adjei, John Portman Design Critic in Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, challenged students to grapple with the compound’s past while envisioning a new future for it at the heart of the Ada Foah community. Dosekun-Adjei, a Lagos-based architect and Creative Director of Studio Contra , aimed to embrace the fort as a “symbolic site of contact between European settlers and traders and the local population,” rather than “rejecting the ruins as part of a painful past and contentious or problematic history.”

With support from the Open Society Foundations, Dosekun-Adjei led a group of students on a trip to Ghana to study the site. In addition to proposing an adaptive reuse of the fort structures that would address unforgiving erosion, students were tasked with developing a cultural program for the adapted site that would be historically sensitive, relevant to Ada Foah residents, and connected to the burgeoning ecosystem of regional arts institutions. Instead of preserving a monument or recovering a ruin, the goal was to transform the existing conditions into what Dosekun-Adjei calls a “generator” that will enrich the cultural life and economy of its surrounding community.

We used a European building constructed in Africa as a site for hybridizing what could be a rediscovered Indigenous approach to architecture and material culture.

Olayinka Dosekun-Adjei

“When we first arrived at the site after a long drive, the sun was blaring, but it was beautiful,” recalled Mariama M. M. Kah (MArch II ’24). “Everyone was taken aback by the sensory and auditory experience: wind gusts were coming off the Atlantic, the air was full of sea salt.” This stunning setting also posed challenges for envisioning resilient material conditions for the studio project. Fort Kongenstein has been worn down over time, defined today as much by absence as by monumentality.

Kah, who had worked in Ghana prior to studying at the GSD, described the fort as a palimpsest characterized by a “layering of history.” The structures that remain embody historical discontinuities: the captain’s house, the oldest extant structure, is built of brick imported from Denmark. The concrete trading post, meanwhile, was constructed sometime after 1850, likely when the British dominated the area. Timber used in each structure has mostly rotted away or been repurposed elsewhere. Recent paintings on the structures’ walls are evidence of community-driven attempts to discover meaningful uses for the building.

Dosekun-Adjei views these challenging conditions as an impetus to critically evaluate the contemporary West African architecture. “We used a European building constructed in Africa as a site for hybridizing what could be a rediscovered Indigenous approach to architecture and material culture.” Looking at the historical fort through the lens of globalization also offered a genealogy of contemporary practices in West Africa, “where so many materials are produced elsewhere, imported very much like this building.” Tracing the histories of these practices back to colonial periods can help architects today rediscover materials and techniques that retain deep local meaning precisely because of their hybridity.

In guiding students through their studio projects, Dosekun-Adjei encouraged them to take imaginative approaches to this hybridity while also foregrounding the need for resiliency. “The idea of a museum or an archive became complicated because we were situated right in front of the sea and coastal erosion was happening at such a rapid rate,” Kah said. “The inevitable reality was looming: the site would succumb to the Atlantic.” Some projects accepted this reality by envisioning temporary structures that would last only as long as the terra firma. Kah addressed this challenge by proposing a robust sea wall structure that would be the centerpiece of similar measures developed in the area.

Courtney Sohn (MArch I ’24) also envisioned a permanent cultural center on the site. “I was thinking about materials in relation to temporality,” she said. “We projected a future for the site in which the materials were going to fall into the ocean. I wanted to build in materials that had resilience even if the rest of the site was lost.” That meant employing techniques from marine architecture to create a structure over the site. As the sea approached, the historical fort would be washed away, representing “a part of the history that we could let go of,” while the new structure, with its new community-centered purpose remained.

The historical legacy of the fort, as Dosekun-Adjei sees it, could help create needed public spaces and institutions in Ada Foah, a village dominated by private tourist development. A re-imagined fort complex could transform Ada Foah into a new kind of public space: a cultural center in the community and a node in the emerging network of small cultural institutions in Ghana. To generate ideas for the building’s program, studio participants visited a number of arts organizations in Accra. With little government support for the arts available, institutions like the Dikan Center and the Nubuke Foundation Art Gallery depend on the ambition and vision of future cultural leaders. This ethos is reflected in the physical structures that house many new arts organizations, many of which employ strategies of adaptive reuse. The Dikan Center, for example, is a photography gallery and library in a refurbished housing complex.

Many of the arts organizations that inspired student projects had hybrid identities, offering their communities more than spaces to contemplate visual arts. The Nubuke Foundation complex is a mix of exhibition galleries and studios, co-working spaces, and other facilities intended to provide broad support for the creative economy.

Partly in acknowledgment of this local need and partly as an exercise in working with different architectural scales, Dosekun-Adjei prompted students to envision both exhibition spaces and other facilities for the community such as classrooms and workshops. Inspired by the role of film production in decolonizing struggles, Kah proposed a program for the fort that included an art house cinema. “I looked at photography and cinema as both a decolonizing method as well as a method for people [in West Africa] to construct their own narratives and archive their history and memories. Photography and cinema are a means of creating beautiful dialectic stories that span generations but still hold true.” Sohn drew upon course discussions about cultural restitution—the repatriation of artifacts removed during the colonial period—as well as her conversations with Ada Foah community members to propose a space for archaeological finds that could stimulate historical and cultural research. Other projects included spaces for a community radio station and production facility, as well as art galleries, classrooms, and workshop spaces.

The GSD student projects, compiled by Dosekun-Adjei and her studio, will become part of a discussion with local leaders and potential funders about the future of the site. The work undertaken as part of the GSD studio suggests that the future of Fort Kongenstein will exemplify an expanded notion of adaptive reuse. Any project that modifies the ruins of the fort will have to address questions of sustainability while engaging with contested historical narratives. As Dosekun-Adjei says, the project will “uncover histories, both architectural and material,” providing new foundations for building in the region and beyond.

Boston Mayor Speaks at the GSD about Urban Forests, Community Resilience, and Environmental Justice

Describing herself as an avowed “tree hugger” from her childhood as part of an immigrant family, when a beloved tree afforded her a sense of peace, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu offered a forceful vision for the role of urban forests in her city’s push for environmental justice and climate resiliency. In the packed Piper Auditorium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Mayor Wu spoke of sharing her lifelong affection for vegetation with her own children, and how a deeply felt connection with trees informs her work advocating equitable provisions of urban forests and parks.

According to Mayor Wu, forested public spaces are much more than a pleasant amenity or even essential resources for public health and environmental well-being. “Parks uniquely create an opportunity for all of us to be in connection with each other,” she said. In so doing, they foster democratic values at a time when democracy itself is under threat.

“The forest may be the last place where we are truly in community with everyone,” she said.

Mayor Wu was a keynote speaker on the opening evening of “Forest Futures: Will the Forest Save Us All?”, a two-day academic symposium at the GSD organized by Gary Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture, and Anita Berrizbeitia, Professor of Landscape Architecture. The symposium brought together designers, researchers, and expert practitioners from various fields to address “risks and threats, initiatives and improved practices, and speculations on a more secure and more just future for metropolitan and urban forests and the species that inhabit them.” (Video recordings of the full symposium are available online.)

Mayor Wu’s appearance coincided with the opening reception for the related exhibition, Forest Futures, on view in the Druker Design Gallery through March 31. Curated by Berrizbeitia, the exhibition features artworks, design projects, and research that explores how forests have become “designed environments.”

The themes of the conference and exhibition find expression in major policy initiatives, including Boston’s Urban Forest Plan , released in 2022. Created in part to redress the legacies of inequality and environmental injustice, the plan identifies strategies to engage Boston’s different communities to “prioritize, preserve, and grow our tree canopy.”

In January, the mayor signed a public tree protection ordinance, one of the plan’s recommendations. Explaining the importance of these measures after her public remarks, Mayor Wu linked efforts to ensure an equitable distribution of tree canopy to existing urban planning processes. “Every time a new building is built we think about the traffic impacts or the curb cuts,” she said, characterizing the Urban Forest Plan as “a recognition that trees are just as important a part of public infrastructure.” Dense tree canopies confer clear public health benefits, and greenspaces absorb runoff, mitigating floods.

The city’s related Franklin Park Action Plan was initiated to revitalize Boston’s 527-acre Frederick Law Olmsted-designed park, which has fallen into disrepair over the years. A self-described “devotee of Olmsted,” Mayor Wu sees Franklin Park, long overshadowed by the iconic landscape architect’s plan for Central Park in New York, as overdue for recognition as “the culmination of Olmsted’s vision and practices towards the later part of his career.”

Demonstrating deep familiarity with the park, Mayor Wu explained how Olmsted integrated his designs with the natural landscape, his work, “perfectly drawn on the natural features, the drumlins . . . the various boulders and vegetation that were already there.” The process to restore the park has been led by Reed Hilderbrand, the landscape architecture practice of which Gary Hilderbrand is a principal.

Olmsted (1822–1903) was an influential designer whose thoughts about the natural world and public space extended into a democratic vision he called “communitiveness .” As the city aims to restore his design for the park, the focus is on more than “the physical characteristics of how he laid out the park and its unique landscape,” Mayor Wu said. “This was supposed to be a place where people from every background could have respite from the needs and obligations of their day-to-day lives. This could be a place where people from all communities could come together and feel a connection. . . That is Franklin Park’s role in the city of Boston today.”

Mayor Wu shared the stage with keynote speaker William (Ned) Friedman, Director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and Arnold Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. Friedman described his “obsessions” with plants and the need to care for trees on their own terms as an act of recognizing their “standing” in our changing world. Edward Eigen, Senior Lecturer in the History of Landscape and Architecture and MDes Domain Head at the GSD, led a wide-ranging conversation after the talks.

The conversation covered the deep ties between the City of Boston and Arnold Arboretum. In a remarkable arrangement, Harvard gifted the land on which the Arboretum sits to Boston. In turn, the city agreed to lease it back for one thousand years, with the option to renew it for another millennium. (The rental price for 281 acres in the heart of Boston? $1 a year.) Pointing to this “sense of longevity,” the Mayor said, “trees help us understand the passage of time.”

After her public remarks, the mayor said that Arnold Arboretum had recently donated to the city 10 Dawn Redwoods , which will be distributed as part of the Urban Forest Plan in accordance with its community-driven values. The tree is the central image on the Arboretum’s emblem, a testament to the institution’s role in conserving what had been thought an extinct species. Now, the trees will also be a symbol of the Urban Forest Master Plan’s commitment to equity, as the redwoods find homes in Noyes Playground in East Boston, Harambee Park in Dorchester, and at a public housing complex in Mattapan.

Remembering George Baird, 1939–2023

The architect and scholar George Baird served on the faculty at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design as the G. Ware Travelstead Professor of Architecture from 1993–2004. He died on October 17, 2023, at the age of 84.

George Baird invented architectural semiotics in the essay, “’La Dimension Amourese in Architecture,” published in arena in 1967 and reworked in the book Meaning in Architecture, which he edited with Charles Jencks in 1969. George’s preliminary study of the semiotics of architecture elaborates the basic structuralist insight that buildings are not simply physical supports but artifacts and events with meaning, and hence are signs dispersed across some larger social text. That insight is then trained on two of the most enduring of late-modernist myths, the building as a totally designed environment (exemplified by Eero Saarinen’s CBS Building, New York) and the building as a value-free servo-mechanism (exemplified by Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt project, Staffordshire).

The repercussions of George’s critique of modernist dogma would prove enormous, of course, extending over the next decade of architecture theory. But if the linguistic analogy—building as text—was perhaps inevitable (semiotics is designed to explain all cultural phenomena, including architecture) and in certain ways already latent in earlier models of architectural interpretation (those of Emile Kaufmann, John Summerson, or Rudolf Wittkower, for example), one must still decide on the most pertinent and fruitful level of homology between architecture and language. That is, is the individual building like a language, or is architecture as a whole like a language? The first view has affinities with traditional treatments of buildings as organic units whose origins and intentions of formation must be elucidated, whereas the second view, which George adopts, shifts the interpretive vocation considerably. No longer is the interpreter’s task to say what the individual building means (any more than it is the linguist’s task to render the meanings of individual sentences) but rather to show how the conventions of architecture enable buildings to produce meaning. Questions are raised about users’ and readers’ expectations, about how a structure of expectation enters into and directs the design of a building (now thought of as a kind of work of rhetoric), about how any architectural “utterance” is a shared one, shot through with qualities and values, open to dispute, already uttered—questions, in short, about architecture’s public life, to which George would turn to fully in The Space of Appearance in 1995.

In semiotic terms, if architecture as a whole is like a language (langue) then the individual building or project is like a speech act (parole), which entails that the architect cannot simply assign or take away meaning and meaning cannot be axiomatic. Rather architecture becomes a readable text, and the parameters of its legibility are what we mean by rhetoric. Rhetoric operates within the structure of shared expectations and demands an ethical, even erotic relationship with the reader: an “amorous dimension,” a phrase George borrowed from Roland Barthes. But rhetoric is not subjective expression. Its procedures are inseparable from processes of argument and justification with respect to the worldly function of architecture’s making sense.

In all this, George approached his study as a scholar-architect. In this role, he had precedents in Alan Colquoun, Kenneth Frampton, and others, then in London. George and Elizabeth Davis married and moved to London, where George basically began to train himself in semiotics and critical theory. It was in London that George was introduced to Hannah Arendt’s Human Condition, about which he wrote,

While she was not a writer about architecture, over the span of subsequent years, she shaped my thinking about architecture more than any other single figure. I remember distinctly the tingle that ran through my body when I first read her scornful comparison of Jeremy Bentham – the very figure whose corpse I passed by most mornings at University College London – with David Hume, who, she sneered, ‘in contradistinction to Bentham, was still a philosopher.’ Arendt’s discussion of utilitarianism confirmed once and for all in my mind, the pernicious influence of contemporary efforts to revive ‘functionalism’ as a basic premise of compelling architectural theory…. All in all, Arendt, [Ivan] Illich, and [Michel] Foucault together created for me a picture of skepticism of, not to say hostility to, the instrumentalized version of enlightenment rationality, which underpinned my critique of architectural functionalism and has stayed with me to the present day.

As I say, I will always think of George as first and foremost a scholar of architecture. I tried to celebrate this conviction when I was invited to introduce his Preston Thomas lectures at Cornell in 1999. I explained that George’s theory placed Claude Perrault’s concepts of positive and arbitrary beauty into active equivalence with the linguistic distinction between langue and parole, or the generalized grammar (langue) and an individual instance (parole) of speech. For what is achieved should not be understood as a simple simile of architecture as a language but rather as the creation out of two previous codes (beauty and linguistics) an entirely new one, unique to architecture, which is capable of recoding vast quantities of discourse, from eighteenth-century French theory’s concern with the natural basis of architecture, to modernism’s mimetic relationship with industry, to postmodernism’s loosening of the classical order. Rewriting such interactions as components in a complex fraction—positive beauty / arbitrary beauty : langue/parole—enables the enlargement of architectural interpretation to include an Arendt-like social communicative function of architecture’s handling of style, materials, and technology, and to measure the social unconscious of different, competing architectural representations in their specific contexts. Indeed, as George uses it, this feature seems to anticipate postmodernism as a kind of revenge of the parole—of the specific utterance, of personal styles and idiolects. Henceforth, worry about empirical method and total design would be completely eclipsed by concerns with the contexts and instances of meaning.

But during my introduction at Cornell, my bad pronunciation of the French “r” destroyed my attempt to explicate Baird’s Barthes-ian reading of Perrault’s parole! George thanked me for the intro, but left it at that: “Michael, thank you, but I just don’t know what else to say.”

George and I talked much about his theory but surprisingly little about his building, substantial though his professional practice was. Once when Martha and I visited George’s Toronto office on a weekend, George projected what struck me as an odd neutrality toward some of the important projects of the firm. About the wonderful Butterfly Conservatory in Niagara Parks Botanical Garden, a completely unprecedented program in a cold climate, he opined, “We should have thought more about being the bugs. Perhaps we thought too much about the children.” George used the same voice he uses at studio reviews. Engaged but neutral, critical yet open minded, reading the project with an Eames-like “Powers-of-Ten” zoom-out to reframe the butterfly’s narrative and recontextualize the architectural object’s confrontation with the world. Perhaps he was performing for Martha and me; George knew we liked his theatricality. But perhaps, on the other hand, this is what a weekend in the office was for him. He was the office consultant in criticality and social aspiration. He was the in-house philosopher.

George was a well celebrated professional, but his habits are those of a scholar.

Harvard Announces Legacy of Slavery Memorial Project

Harvard University has recently announced an international open call for the development of a new memorial to enslaved people on its campus in Cambridge. The Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery (H&LS) Memorial Project Committee “invites artists, architects, designers, multi-disciplinary teams, and other creators to express their interest in conceiving a site or sites on Harvard’s Cambridge campus for commemoration and reflection, as well as for listening to and living with the University’s legacy of slavery,” according to a statement released by the University. The deadline for the application is February 20, 2024.

In 2022, the H&LS report recommended “that the University recognize and honor the enslaved people whose labor facilitated the founding, growth, and evolution of Harvard through a permanent and imposing physical memorial, convening space, or both.” Nearly a year after the report’s release, the Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery Memorial Project Committee will lead an effort to “memorialize enslaved individuals whose labor was instrumental in the establishment and development of the University as an institution, and define what a memorial could entail, options for where it could reside, and the process for its creation.” The thirteen-member committee is co-chaired by Tracy K. Smith, professor of English and African and African American Studies and the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at Harvard Radcliffe Institute, and Dan Byers, the John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Director of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

The committee seeks “creative visions that activate and make visible complex dynamics, such as: permanence and vitality; honor and rebuke; ecology and the built environment; institutional interest and the common good.” Submissions will be accepted from individuals, collaborations, and teams without limitations on age, education, or career and professional status. Applications will be judged on their vision, committment to collaboration and partnership, and design expertise. Round one submissions must include team details, a portfolio, three references, and a 500-word narrative responding to the theme of reckoning and commemoration. The timeline and completion of the memorial is anticipated for the summer of 2027, and the University has budgeted approximately $4M for this project inclusive of artist fees, materials, fabrication, and construction costs. Additional funds from the H&LS $100 million endowment may be available for short and long-term planning, programming, and engagement.

Read the Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery Memorial Request for Qualification (RFQ) and a Q&A interview with the Memorial Committee co-chairs for more information about the project.

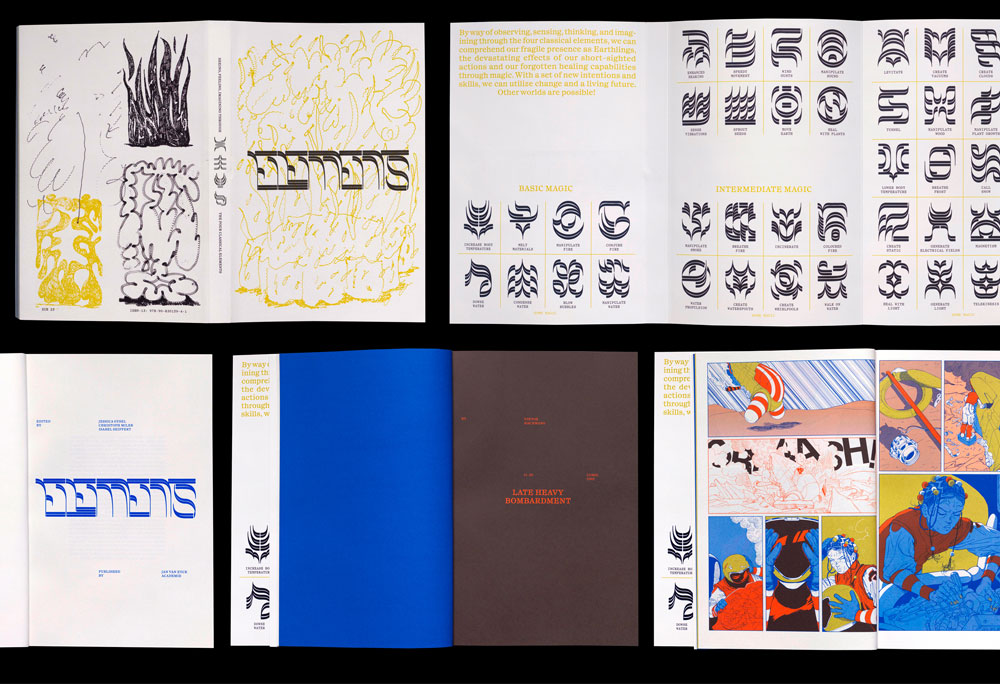

Design and Time: An Interview with Offshore

The public program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design features speakers in the design fields and beyond. The series of talks, conferences, and conversations offers an opportunity for the public to join members of the GSD community in cross-disciplinary discussions about the research driving design today.

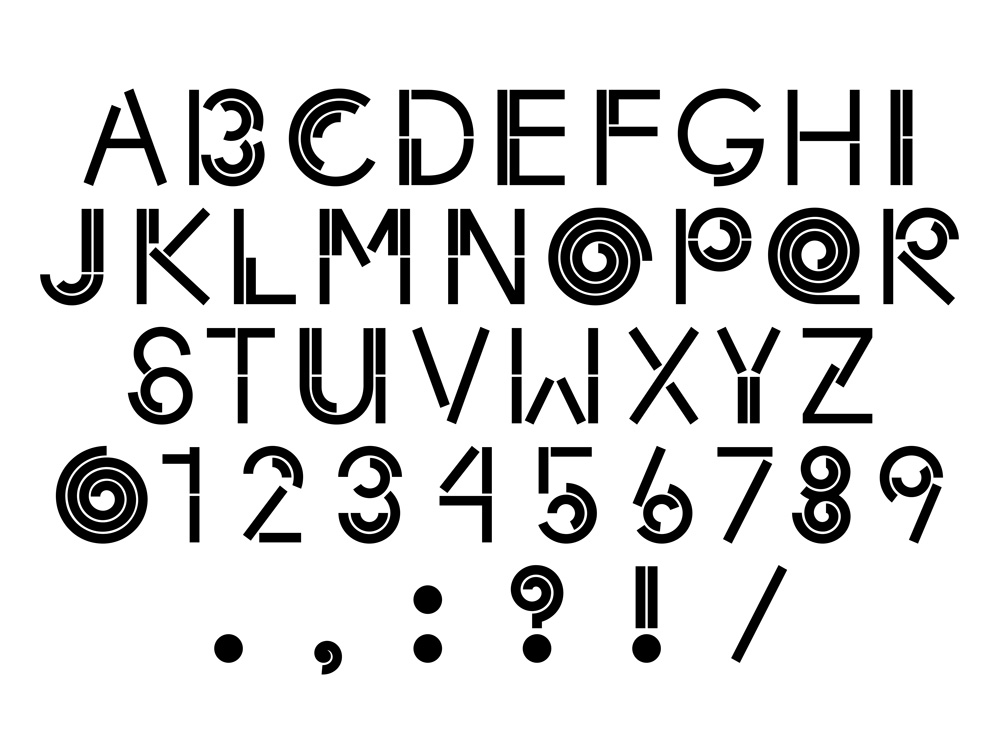

Each year, in an effort to extend an invitation to these programs as widely as possible, the GSD asks graphic designers to create a visual identity that conveys the program’s spirit and mission. For the 2023–2024 academic year, Offshore , the design practice of Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miler, took up that challenge. They created print and digital materials featuring a swirling motif and a spiral-like typeface that distill the energy and intellectual curiosity of the School’s events. To better understand how graphic design relates to the GSD’s public program, Art Director Chad Kloepfer exchanged questions with Miler and Seiffert over email.

Chad Kloepfer: Through innovative printing and custom typography, this year’s poster is a literal whirlwind of color and type. What did you hope to convey through this treatment?

Offshore: A whirlwind of color and type—that is such a nice description. The graphic language for architecture-related projects often features monochrome or more toned-down and serious visual gestures. Additionally, the pandemic years have felt very monotonous in many ways. We wanted to bring some energy and liveliness to this project. It was important for us to convey a vibrant, dynamic, and, to some extent, action-oriented mood.

There is a structured but organic feel to both the typeface and layout, the spiral being a predominant gesture. How did you arrive at this graphic device?

During the design process, we were very focused on striking a balance between sharp, clear, and bold graphical forms while allowing movement and avoiding rigidity. To us, this represents a commitment to precision that does not feel “square,” if that makes sense. The gesture of the spiral comes from the idea that this visual identity lives for one academic year, one cycle, so to say. It can be a very intense and dense period, with a lot of things happening at the same time. We wanted to convey that visually.

I really love the typeface, especially when the circular glyphs are animated. Can you speak a little bit about the development of this typeface?

There are quite a few typefaces out there that feature spirals in their glyphs. But all of those felt either too retro or too organic for this purpose. We were keen to be precise and playful at the same time–to simultaneously create something very constructed and quite dynamic. We made a few hand drawn sketches to find the general proportions and feeling. We also asked our friend Jürg Lehni, who created paper.js and the Scriptographer plugin for Illustrator back in the day, to create a small spiral tool for us. This made it easier and faster to draw very precise spirals with the parameters we needed for the various glyphs. We hope to extend the glyph set with lowercase and more punctuation later this year.

Could walk us through the printing process for the poster?

We used offset printing to produce the poster. This gave us access to radiant spot colors, which was essential for creating the vibrancy we were aiming for. The first step was to print the background layer and the big spiral in black and fluorescent red. The silver layer with all the typographic information cut-out was applied in the second step. This way the typography is displayed by revealing the first printing layer, thereby creating a vivid interaction of the overlapping elements.

Something I really admire in your body of work—and this year’s poster is no exception—is how layered it all feels. I mean this both visually and conceptually. Like a root system, we are taking in what is above ground, but it also hints to non-visible layers that are fun to unpack. Could you discuss the conceptual side of your process? What was the thinking behind this public program identity?

The deeper roots of our approach might be found in our latest fascination for the contemporary discourse around time. Today, many artists and writers are challenging the conventional Western idea that history moves in linear fashion. They are emphasizing the non-linear nature of time instead, thinking of history in loops, dialectics, time bangs, and spirals. For example, Ocean Vuong writes in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: “Some people say history moves in a spiral, not the line we have come to expect. We travel through time in a circular trajectory, our distance increasing from an epicenter only to return again, one circle removed.” We think many of those alternative notions of time are beautiful and fascinating, since they imply a more complex, long-term and intertwined relationship of humans, more-than humans, and the environment. In many ways, these concepts are counter-chronologies, challenging today’s prevalent version of standardized and linear time that serves efficiency, productivity, and a mainly economic perspective on progress and growth. These alternative, nonlinear views on time–some of them in the shape of a spiral–propose a less anthropocentric position, which might help us to synchronize ourselves with a world that is made up of multiple rhythms of being, growth, and decay.

Your portfolio has a striking visual range. Rather than following a set stylistic approach, you seem to generate a vernacular response to the subject matter of each project. What are the underlying continuities within your stylistically diverse body of work?

One underlying continuity within our work is our ongoing interest in multilayered narratives. Stories define who we are, sociologist Arthur W. Franke writes. They do so because they always “work on us, affecting what we are able to see as real, as possible, and as worth doing.” The aesthetics of each project develop from this and similar questions. What style communicates the story we want to tell? What tools do we need to use in order to create the aesthetics we envision? What production processes emphasizes our idea?

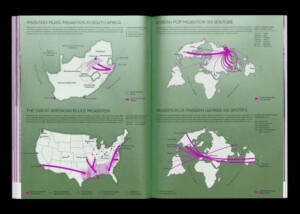

In the last five years, we have built manifold narratives, tackling issues ranging from migration, ecology, and interspecies relations to visual histories and design education. Working with various media—publications, websites, drawings, and exhibitions—we are interested in telling stories in an engaging, often multilayered fashion. Unfamiliar maps, vibrant visuals, symbols that expand and challenge the written language, photography, and illustration can coexist in our plots; they create rhythm, intertwine, and unfold unfamiliar perspectives. We tell stories by exploring, questioning, and transgressing the defined spaces of the discipline of Graphic Design while still staying committed to form, aesthetics, and craft.

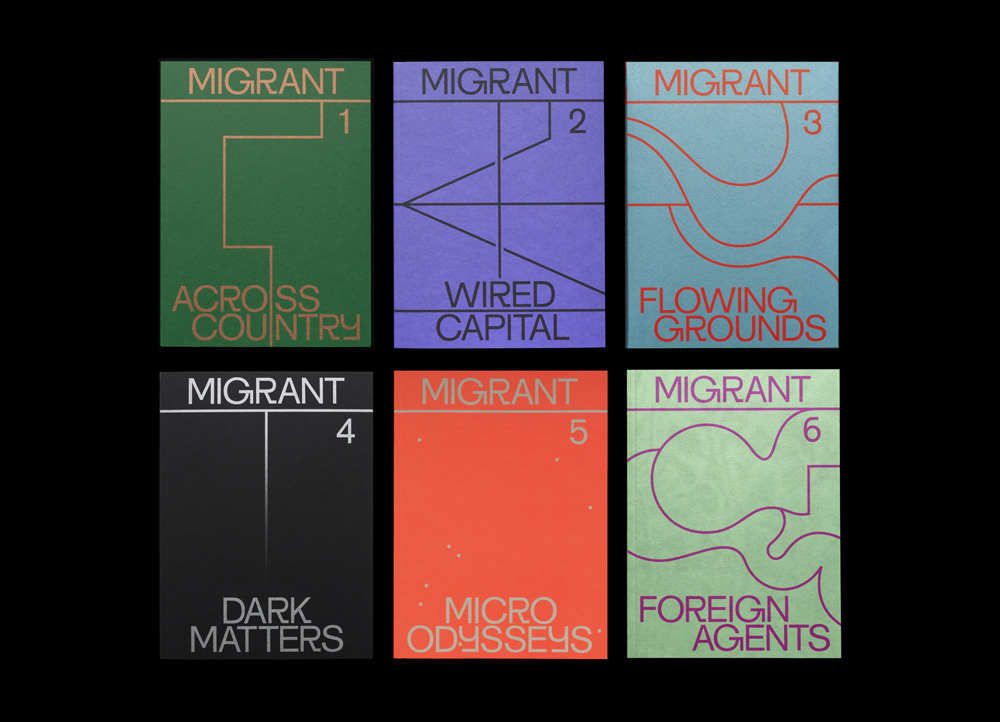

One of the projects that brought your studio to our attention is the publication Migrant Journal , which ran from 2016–2019. You were not just the designers of this publication but also helped found it and were co-editors. Can you speak a little bit about what Migrant Journal was/is and what it meant for your studio?

Migrant Journal was a six-issue publication exploring the circulation of people, goods, information, ideas, plants, and landscapes around the world. Together with our contributors, we looked at the transformative impact this circulation has on contemporary life and spaces around us.

Our endeavor with Migrant Journal has been from the start to look at the world through the lens of these migratory processes—dealing with questions of belonging, national identity, cultural shifts, financial systems, but also landscape transformation, the weather, movement of animals, and global food networks. The idea was born in 2015 when the so-called migrant crisis in the Mediterranean Sea was seemingly the only topic in the news. We felt that there was a huge lack of in-depth information about the complexity of the issue, global interrelations, and the broader concept of migration. In a world of a polarized and populist political climate and increasingly sensationalist media coverage, we felt that it is more important than ever to re-appropriate and destigmatize the term migrant.

In order to break away from the prejudices and clichés of migrants and migration, we asked artists, journalists, academics, designers, architects, philosophers, activists, and citizens to rethink the approach to migration with us and critically explore the new spaces it creates. A printed journal provided a platform for multiple disciplines and voices to talk about an intensely interconnected world that creates a multitude of interdependent forms of migration.

The decision to produce a magazine, and not make a website or a book, was purposeful. We strongly believe that printed publications can create a reading experience that lasts longer than most ephemeral bits of information on the internet. As soon as it’s online, it’s lost in the stream of information, and we didn’t want this. Print is still the technology that ages better than any other carrier of information.

Maps are an integral component of migration. They are all about movement, territory, and space. So it felt very natural to use the technique of mapmaking as a narrative tool for our publication. Maps, as one major component of Migrant Journal, are woven into a diverse set of editorial formats, like essays, images, infographics, reports, and illustrations. Through the materiality of the object we were able to translate complex issues into a format that provides various points of entries in a multilayered manner.

It’s our founding project and has heavily shaped our way of working in many aspects of the practice. At the same time, it defined our studio profile and influences, until today, the projects for which we receive commissions.