Belonging (1-unit Module 2 Lecture)

What differentiates a building designed in Paris from one in Jerusalem, or Houston from one in Amsterdam or China or the Arabian Peninsula? A national museum for the Sikh’s or the Cherokee Nation?

Over my career I have been asked to design projects for people and places that I didn’t know. In Africa, in Iran, in Asia, and in Texas to name a few. My mission going into each relationship was always to immerse myself in the culture and the place; to extract some clues that would support my belief which is that when architecture represents the essence of the place where it is built, it resonates with people in a way that is long lasting and profound. My belief is that architecture has the power to bring people together, to unite all kinds of differences, and that as architects we have a deep responsibility to create buildings and places that BELONG.

But how does an architect born in Israel, who finds a life in Canada and then here in Cambridge have the knowhow and sensibility to design for a people and place that they simply do not know? And how can we all learn and be better at walking in other people’s shoes?

How does a design become particular to place and program? As architects, we must decipher the secrets of the site, understand the climatic and environmental context, reflect upon the cultural heritage and history, and study the technology of construction that is most appropriate.

In our own practice over the past fifty years, we have been confronted with a series of significant projects in a wide variety of geographies and cultures, including those on home territory, which framed for us the issue, can we achieve buildings which will be perceived to have a strong sense of belonging? I will share a series of stories via the projects and the people I have worked with for over fifty years. In three lectures, followed by discussion, I will analyze from our own work, often with references to the work of others, successes and failures in the quest for achieving designs that belong. This 1 credit course will also include a visit to our studio space in Somerville to discuss further the subject matter.

To receive credit, students will be required to attend all four sessions. After each lecture there will be a discussion session. At the end of the course, students will prepare a paper on their findings from the course. The course meets four evenings: March 26, April 2, April 9 ,and April 16. This course is not open to cross-registration.

If you are a GSD student and interested in enrolling, please add this course to your Crimson Cart. The registrar’s office will officially enroll you on February 10 and do another round of enrollments on March 24. Note that the registrar’s office will officially enroll you in the course from your Crimson Cart, EVEN IF IT WOULD MEAN YOU WILL BE EXCEEDING YOUR MAXIMUM UNITS. You will not need to receive program director approval for exceeding your maximum units to be enrolled in this course. Those who exceed the following units by degree program will be charged extra tuition in early April: 20 units for MDES, 22 units for MDE, and 24 units for all other GSD programs.

Magna Parens Materia: Hybrid Stone and Timber Mid-Rise Building

Over the last century, architects have been driven by market conditions to build with the highest possible combination of CO2-heavy materials, including steel and reinforced concrete frames filled with glass, aluminum, and fired clay bricks. This studio speculates on the potential of turning the construction industry from one that emits a significant amount of CO2 to one that sequesters it. By designing in stone (a partial substitute for reinforced concrete and steel) and timber (a heavy carbon sequestrator), we explore the feasibility of lowering the carbon footprint of new mid-rise buildings. At the same time, while our studio followed a hybrid approach employing stone and timber, we recognize the necessity of designs that may include other mixes of (potentially carbon-intensive) materials. The studio begins with a crash course in stone’s material properties—structural, tactile, textual, financial, and carbon cost—and, thanks to “source to product” suppliers and specialists, we continue by touring quarries, stonemasons’ workshops across Belgium and the UK, and buildings in London (where student projects are set, in the Earl’s Court development of the London framework plan). This studio aims to recalibrate practice for real-world applicability, engage with building technology, sustainability, and codes, and establish a reciprocity between technical and conceptual aspects. Magna Parens Materia: Hybrid Stone and Timber Mid-Rise Building is a studio report from the Spring 2024 option studio Magna Parens Materia jointly taught by Hanif Kara and Amin Taha at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Series design by Zak Jensen and Laura Grey Report design by Robin Albrecht Softcover, 256 pages, 17 x 24.5 cm“Radical Atlas of Ferguson, USA” by Patty Heyda MArch ’00 Published by Arcadia Publishing

Patty Heyda MArch ’00 recently published Radical Atlas of Ferguson, USA with publisher Belt/Arcadia Publishing. The book contains over 100 maps that chart the systemic forces and municipal planning policies that led to poverty, racial segregation, and police targeting in Ferguson, Missouri. Radical Atlas of Ferguson, USA rethinks what maps can be and who our cities are built for.

Heyda examines the distribution of libraries, fast-food chains, airport runways, and Fortune 500 companies in North St. Louis County to illustrate how city planning and design affect residents’ quality of life. “What we can see in Ferguson and North County is happening in every American city. The patterns are, in fact, really pronounced here,” said Patty Heyda in an interview with St. Louis Public Radio .

Photo courtesy of Patty Heyda.

The Renovated Gund Hall: A Paradigm for the Revitalization of Mid-Twentieth-Century Architecture

Harvard Graduate School of Design students returned for the fall 2024 semester to find Gund Hall transformed. Yet the iconic building looked much the same as it had since opening a half century ago. And this was indeed the point. Over the summer, a meticulously planned renovation enhanced the facility’s energy performance, sustainability, and accessibility while conserving its original design. Led by Bruner/Cott Architects, this project has transformed Gund Hall into a paradigm for the rehabilitation and stewardship of mid-twentieth-century architecture.

Designed by Australian architect John Andrews (MArch ’58), Gund Hall opened in 1972 to house Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). Since this time, the building’s glass-enclosed five-story studio block, known as the trays, has served as the GSD’s physical and metaphorical center—where students work, interact, and exchange ideas. The trays have been quite successful as a workspace and social condenser, as Andrews envisioned, but less so in terms of environmental consciousness and user comfort. Single-pane glazing and minimally insulated exposed concrete, commonplace at the time of construction and used by Andrews in a forward-thinking fashion, ultimately made the building difficult to heat and cool. Studies preceding the renovation revealed that the trays, which account for 28 percent of Gund Hall’s floor area, were responsible for 46 percent of the building’s energy consumption.

Alongside these financial and environmental costs came a very human one: within the trays, students experienced thermal conditions that ranged from sweltering heat to hand-numbing cold, all while grappling with glare from direct and reflected sunlight and leaks from the stepped roof. Andrews’s experimental design gave rise to an impressive building marked by vulnerabilities that future generations, with access to advanced technologies, needed to address.

David Fixler, lecturer in architecture at the GSD, is chair of the Building Committee, which consists of faculty representing the school’s three core disciplines and oversees the renovation project. According to Fixler, the idea to upgrade the trays’ glazing “had been in and out of the GSD’s eye for the better part of two decades.” The past five years saw the envelope project “revived with a strong emphasis on comfort, energy efficiency, and larger sustainability goals to prove that a building like Gund Hall,” which predates contemporary energy-conservation concerns, “can be made a more environmentally friendly place.” This was a complicated proposition, however, as the renovation’s mandate was to improve Gund Hall’s energy efficiency while acknowledging the stewardship value in conserving Andrews’s original design. In addition, as Fixler noted, “Harvard is a place known for innovation and great design, and we wanted to reflect that as well.”

To develop a realistic scope for the summer renovation—itself the first phase of a multi-year renovation project—the Building Committee worked closely with Boston-based Bruner/Cott Architects, specialists in historic preservation. Project architect George Gard, associate at Bruner/Cott and GSD alumnus (MAUD ’14), noted that the design team’s focus rested on “two main pillars: conserving Gund Hall, and making its facade world-leading in performance.” Harnessing the technology to create a first-rate facade, Gard clarified, was “the easy part; the hard part was understanding the building’s conservation value and marrying the technology to it” while meeting strict dimensional parameters for the glazing members. Jason Jewhurst, Bruner/Cott principal-in-charge, offered an illustrative example, citing the design team’s decision to keep the 50-year-old facade support steel within the studio’s original glazing system. This move aligned with the building’s preservation and helped minimize carbon emissions, yet it also underscored a challenge applicable to much of the Gund Hall renovation: “how do we work with the existing fabric and elevate it with new technology?” Jewhurst asked. As Fixler observed, in the planning and design stages as well as in the field, “this project involved a lot of artistry.”

A primary achievement of the ambitious renovation, which followed a tight construction schedule initiated after commencement in May, involves the replacement of the glass encasing the trays. In total, this amounts to 1,617 glazing units equaling a glazed area of 15,475 square feet. The east curtain wall and clerestory windows employ triple-pane glass, while a custom hybrid vacuum-insulated glass (VIG) composite contributes an additional layer of insulation to the north and south curtain walls. By leveraging the insulating properties of the internal vacuum and marrying it to an additional layer of conventional insulating glass in a sandwich that is overall only a few millimeters thicker than conventional double glazing, the hybrid VIG offers unprecedented thermal resistance. These hybrid units can deliver energy performance that is two to four times better than standard insulating glass and up to ten times more efficient than single-pane glass. While this technology has developed a strong track record in Europe, the Gund Hall renovation is among the first projects in the United States to employ hybrid VIG on a grand scale.

Through choice of glass and special coatings, the reglazing project markedly enhances the balance, distribution, and quality of light within the studio, which is augmented by improvements such as the installation of motorized window shades to help mitigate glare and heat gain from direct and reflected sunlight, and upgraded under-tray lighting for better illumination. Widened exits to the terraces make these outdoor spaces wheelchair accessible for the first time in Gund Hall’s history. In addition, the construction team repaired areas of deteriorating concrete on building’s exterior.

In terms of sustainability, the renovation of Gund Hall exceeds Massachusetts’s stretch energy code for alterations, rendering the building a step above the base code in terms of energy efficiency. Calculations project that, moving forward, the renovated building will save approximately 18,000kg of CO2 emissions per year, resulting in a nine-year carbon payback for the project. Gund Hall will see a 22.2 percent reduction in energy use intensity and a 19.1 percent reduction in utility costs.

Of equal significance to these outcomes are the improvements in user friendliness that stem from the renovation. Not only will everyone be able to access the trays’ outdoor terraces, but “for the first time in over 50 years, the trays will be warm in the winter, cool in the summer, and we won’t have rain leaking onto our desks,” proclaimed Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture. Indeed, alongside the upgrades to the building’s efficiency and sustainability, these qualitative enhancements position Gund Hall as a model for the conservation and revitalization of mid-twentieth-century modern architecture.

“When John Andrews was originally tasked to design a new facility for the Departments of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Planning and Design,” Whiting noted, “he surprised his clients with a unique building that was at once solid and transparent and that prioritized the student body, united within an enormous, light-filled, single space. Though much has changed since Gund Hall first opened in 1972,” she continued, “the careful rehabilitation of the structure underscores the school’s commitment to this same priority: our students.”

Project Team:

- Bruner/Cott Architects – Design and Executive Architect (Prime Consultant)

- Jason Jewhurst, FAIA (Principal-in-Charge)

- George H. Gard, AIA, Associate (Project Architect)

- Henry Moss, AIA, LEED AP (Consulting Principal for Preservation & Design)

- Mridula Swaminathan, Assoc. AIA (Project Designer)

- SGH – Building Envelope Consultant, Structural Engineer

- Redgate – Owners Project Manager

- Lam Partners – Daylighting Consultant

- Vanderweil Engineers – Sustainability, Electrical Engineer, Mechanical Engineer

- Kalin – Specifications

- Jensen Hughes – Building and Accessibility Code

- Heintges – BECx

- Shawmut Design and Construction – Construction Manager

- A&A Window Products – Glazier (Key Sub-Contractor)

- Oldcastle Building Envelope (OBE 360) – Curtain Wall and IGU Fabricator (Key Supplier)

- Vitro – VIG, Glass Substrate, and Glass Coating Supplier (Key Supplier)

GSD Building Committee Faculty Members:

- David Fixler, Lecturer in Architecture and chair of the Building Committee

- Anita Berrizbeitia, Professor of Landscape Architecture

- Gary Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture

- Grace La, Professor of Architecture and chair of the Department of Architecture

- Mark Lee, Professor in Practice of Architecture

- Rahul Mehrotra, Professor of Urban Design and Planning and the John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization

- Farshid Moussavi, Professor in Practice of Architecture

- Holly Samuelson, Associate Professor of Architecture

- Ron Witte, Professor in Residence of Architecture

GSD Alumni Involvement:

- George H. Gard, AIA, Associate, Bruner/Cott Architects, MAUD ’14

- Henry Moss, AIA, Consulting Principal, Bruner/Cott Architects, MArch ’70

- LeeAnn Suen, AIA, Architect, Bruner/Cott Architects (Former), MArch ’17

- Whitney Hansley, AIA, Assistant Project Manager, Redgate (Former), MArch ’16

- Dan Weissmann, AIA, IALD, IES, Associate Principal, Lam Partners, MDes ’12

- Royce Perez, Associate, Heintges (Former), MArch ’17

- Holly Samuelson, AIA, LEED AP, GSD Building Committee Member, DDes

- Farshid Moussavi, ARB, RIBA, RA, GSD Building Committee Member, MArch II ’91

- Gary Hilderbrand, FASLA, FAAR, GSD Building Committee Member, MLA ’85

- Mark Wai Tak Lee, AIA, GSD Building Committee Member (Former), MArch ’95

- Grace La, AIA, GSD Building Committee Member, MArch ’95

- Rahul Mehrotra, GSD Building Committee Member, MAUD ’87

Mete Sonmez MArch ’08 and Neyran Turan DDes ’09 Named a 2024 Design Vanguard by Architectural Record

Nemestudio , a Bay Area-based architecture practice founded by Mete Sonmez, MArch ’08 and Neyran Turan, DDes ’09 has been selected as part of the 2024 Architectural Record Design Vanguard. This annual award program recognizes ten leading architectural firms and individual practitioners globally who represent the promise of the most innovative architecture work in the field and will lead the profession in the future.

“As Nemestudio’s theoretical research and built work evolve, they continue to call for what Turan terms ‘planetary imagination,’ the critical need to address, with greater awareness and creativity, the mounting threats to our environment—as well as the powerful forces too often entangled with them.” Click here to read the full firm profile from Architectural Record.

Follow Nemestudio on Instagram: @nemestudio .

Photo courtesy of Neyran Turan.

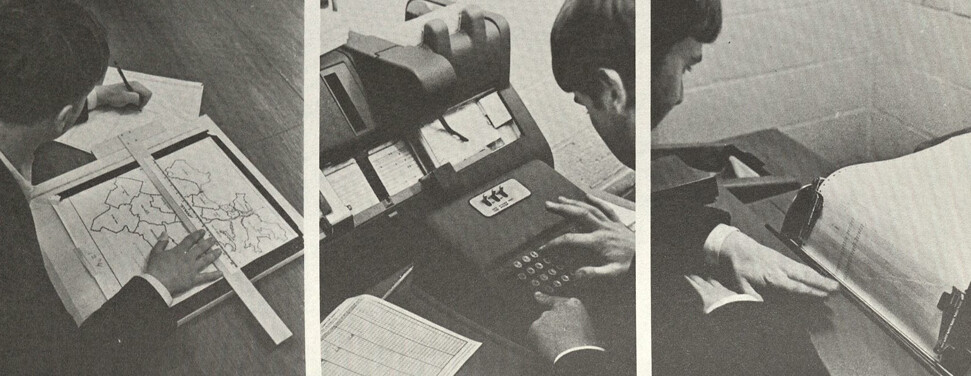

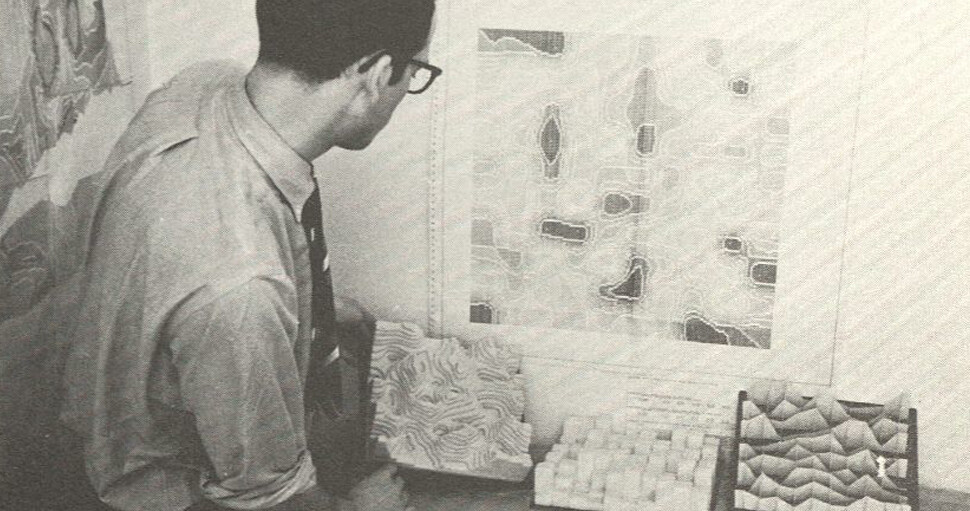

A New Way of Seeing: The Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis

In 1965, as students protested the escalating war in Vietnam, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, and the federal government sought to revive faltering cities through urban renewal programs, Harvard’s Graduate School of Design launched a groundbreaking initiative: the Laboratory for Computer Graphics. Over the next quarter century, this multidisciplinary research group developed programs for automated mapping and spatial analysis that changed the ways we understand and create the world around us, from forecasting the weather to designing buildings. The lab served as an incubator for computer-based technologies that pervade all aspects of contemporary life—including the ability to avoid traffic back-ups, courtesy of the now-standard mapping software in today’s vehicles.

Origins: Howard Fisher and SYMAP

Howard T. Fisher was no stranger to Harvard. He had earned his undergraduate degree there in the mid-1920s and then studied architecture at the school, prior to the advent of the Graduate School of Design (GSD). Fisher, who for a time specialized in prefabricated housing and commercial architecture, was a versatile designer; a colleague would later describe him as “a complete architect, planner, master builder, inventor, environmental scientist, teacher, and scholar . . . truly a Renaissance man of the 20th century.”1 Yet, those who knew Fisher best characterized him, above all, as a problem solver—a trait that prompted his return to Harvard in 1965.

In the decade following World War II, the flipside of American prosperity was urban turmoil. People with means abandoned the city, opting instead for suburban life. Businesses soon followed, leaving in their wake empty downtown commercial districts, deteriorating neighborhoods, and substandard living conditions. Cities were in crisis, and the search was on for potential solutions, many of which drew on the era’s developing technologies—including the computer. It was in this cultural milieu that Fisher, practicing and teaching in Chicago in the early 1960s, devised a software program to create legible maps from complex data.

Fisher’s creation, named SYMAP (short for Synagraphic Mapping System), was conceived as “a new way of seeing things together as a whole.”2 In other words, SYMAP could analyze information from many sources and present it so that relationships were readily visible to planners, designers, or anyone. Furthermore, while earlier software programs required users to physically assemble the layers of a thematic map (essentially a map that tells a story about a place), SYMAP used a computer to create an entire thematic map, representing data by using contour lines, shading, patterns, and eventually color. To create such a map, the programmer manually keypunched data on cards, brought them to a computing center for processing, and returned for the printout hours or days later.3 In the mid-1960s, Harvard had a single computer for such purposes; registered users were permitted one visit per day, and due to processing time, it could take up to a month to produce a single map.4 Nevertheless, SYMAP’s ability to synthesize material and generate information-laden maps was an improvement, both in the sophistication of analysis and the time required to create such maps sans computer.

Given the precarious state of American cities at the time, SYMAP’s potential applications in the realm of planning and design offered great promise.5 This appealed to the philanthropic Ford Foundation, which sought to further the public welfare by “identify[ing] and contribut[ing] to the solution of problems of national and international importance.”6 Foundation officials signaled that they would be open to funding Fisher’s continued research, however he first needed a university to house this research. Fisher thus turned to his alma mater, where he found a champion in Harvard GSD dean Josep Lluís Sert.

Fisher and SYMAP relocated to Harvard in February 1965 where, within the GSD, he established the Laboratory for Computer Graphics (LCG).7 That fall, through the GSD’s Department of City and Regional Planning, he submitted a proposal to the Ford Foundation, which promised $294,000 (equivalent to nearly $3 million today) “for research and training in the use of computers to make maps of social and economic features of cities.” This grant to the GSD, to run through 1969, formed part of a larger effort to address the ongoing crisis in American cities by, as the foundation characterized it, “harness[ing] computer-based analysis to the study of urban problems.”8 Subsequent funding for the LCG would come from a variety of sources, including the sale of proprietary software; correspondence courses, professional development seminars, and conferences; local and federal government contracts; and grants from institutions such as the Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation.

Early Years

Major funding in hand, Fisher wasted little time in attracting attention—and talented researchers—to the LCG, launching an ambitious lecture series in April 1966. Held weekly throughout the spring and fall semesters that year, these meetings attracted participants from throughout Harvard and beyond. Regular attendees, dubbed “Computer Graphics Aficionados,” engaged with distinguished speakers from many disciplines, including geography, cartography, engineering, economics, sociology, psychology, anthropology, classics, transportation and city planning, urban design, and landscape architecture.9

Mathematical geographer William Warntz, known for population analyses of social and economic patterns, spoke at an Aficionados session on the topic of statistical surfaces. Warntz soon became a key figure in the LCG, leaving his position with the American Geographical Society to join the GSD in 1966 as professor of theoretical geography and regional planning, and the LCG’s associate director. When Fisher retired two years later, Warntz moved into the role of director and added “Spatial Analysis” to the group’s name, signaling the lab’s expanding focus. Thus, from 1968 on, the organization was officially known as the Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis.

In fall 1966, geographer and urban planner Allan Schmidt was featured at an Aficionados meeting, where he discussed the role of computer mapping in the planning process. Shortly thereafter Fisher persuaded Schmidt to leave his position at Michigan State University and assume a new post at the LCG, starting in spring 1967. For the next 15 years, Schmidt remained at the lab in various capacities, including director (1971–1975) and executive director (1975–1982).

Another key figure who took part in the LCG’s formative years is Carl Steinitz, now Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning Emeritus at the GSD. Steinitz traced his involvement to a fortuitous 1965 encounter with Fisher, where Steinitz—then a graduate student in city and regional planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology—learned of SYMAP. With Fisher’s tutelage, Steinitz used SYMAP to analyze and map data for his doctoral thesis, which explored Central Boston’s urban features in relation to his advisor Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City (1960).10 In 1966, Steinitz accepted a joint post at the GSD: assistant professor in the Departments of Landscape Architecture and City and Regional Planning, and research associate at the LCG.11 He would stay with the lab through 1972.

By the end of the 1966–67 academic year, the lab employed 29 people, including GSD graduate students, Harvard undergrads, and experts from many fields. Staff numbers would fluctuate in the coming years, depending on specific research projects and funding. Despite being an organization within the GSD, the LCG was housed for its first seven years not in Robinson or Hunt Halls, but in the basement of adjacent Memorial Hall. In 1972, the lab joined the rest of the GSD across the street in the newly completed Gund Hall, occupying space on the 5th floor.

Research and Outreach

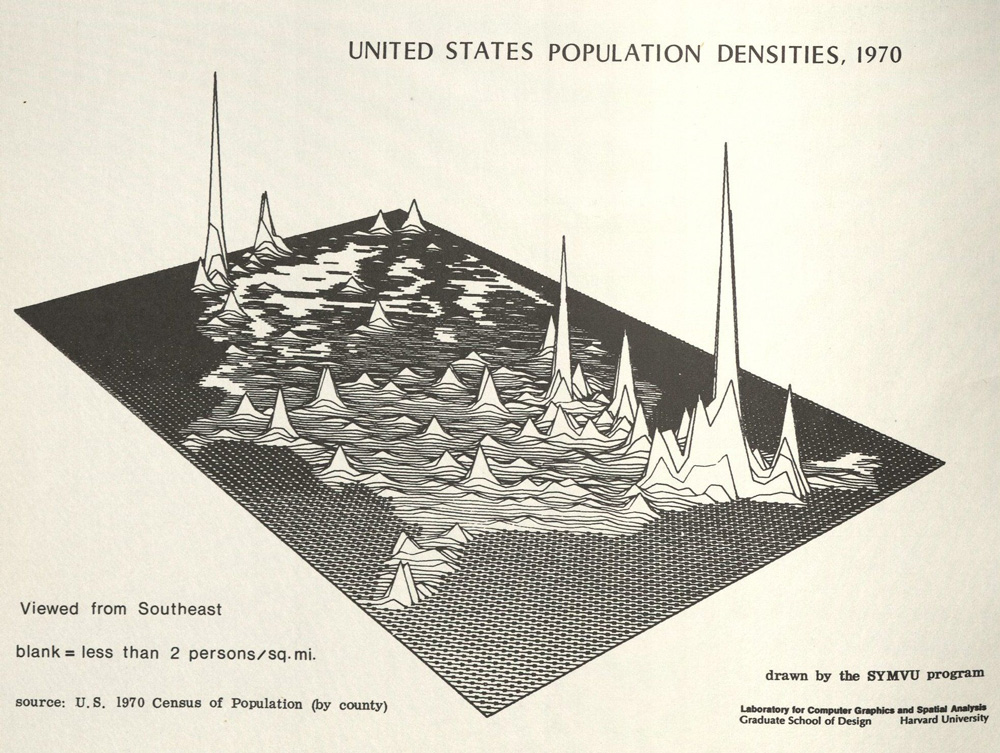

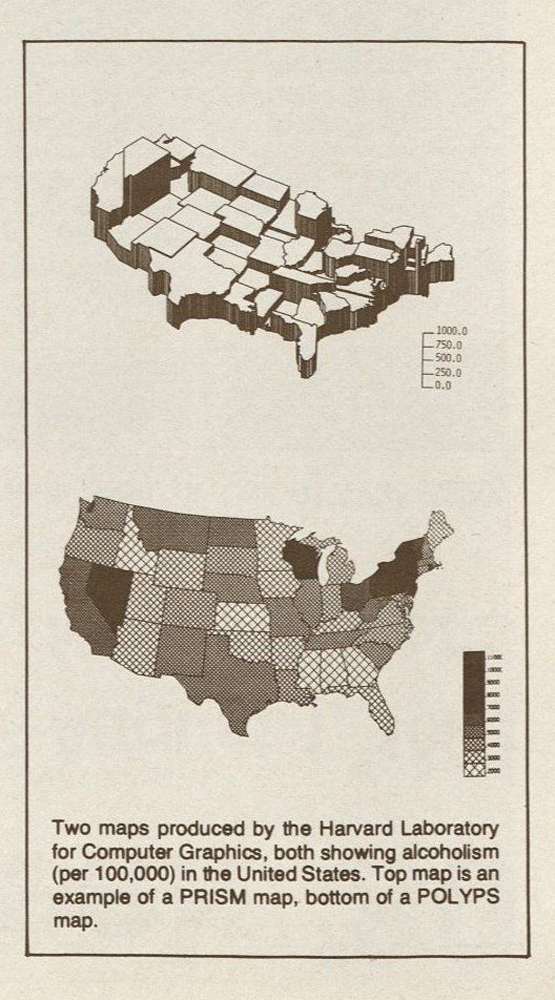

Fifty years after its founding, Steinitz described the LCG’s early research as falling into two basic categories. The first stemmed from SYMAP, involving “investigations into computer graphic representation of spatially and temporally distributed data.”12 This research included time-series maps of a storm’s progression, three-dimensional data displays, and maps that conveyed large data sets, such as early census maps for New Haven, Connecticut.

The lab’s second area of inquiry, according to Steinitz, “related to city and regional planning, landscape architecture and architecture, focused on the role of computers in programming, design, evaluation and simulation.”13 These efforts included research that drew on SYMAP and other programs to analyze data—such as a region’s possible uses, resources, and vulnerabilities—and generate models to assess future land-use impacts, which could in turn guide design and development decisions. This methodology, envisioned by Steinitz in 1967 to apply computer analysis and mapping to environmental planning, is today widely known as geodesign.

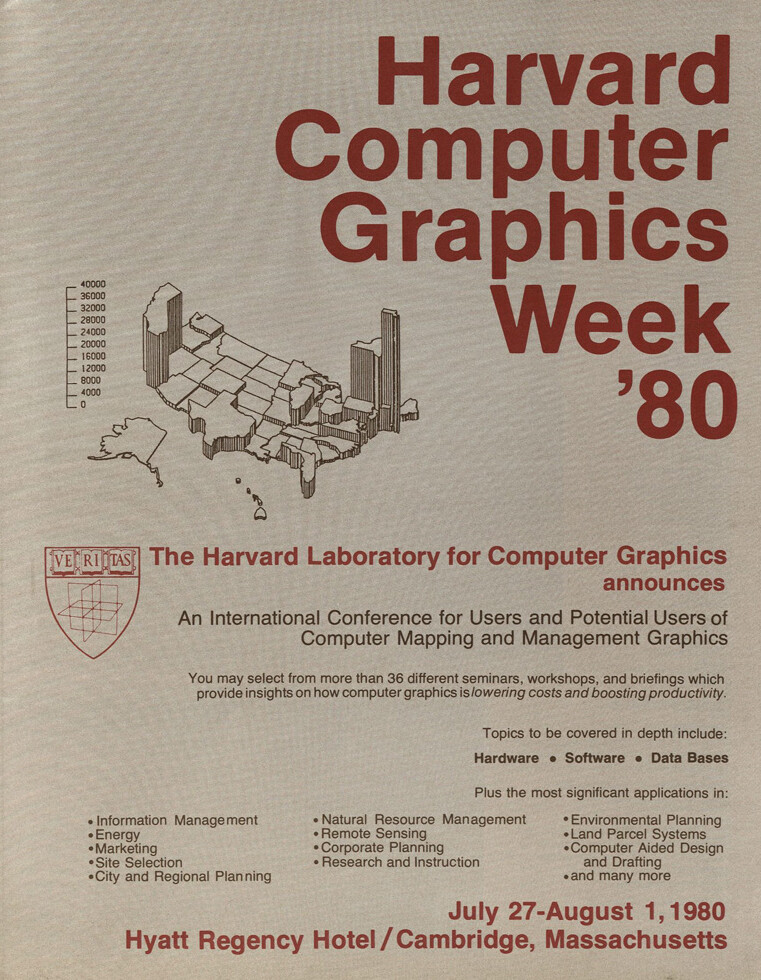

In tandem with its research and development activities, the LCG circulated its work through a variety of means. The lab sold SYMAP and later programs commercially, with nearly 1000 practitioners throughout the world participating in the lab’s correspondence training course, initiated in 1966. Beginning the following year, the LCG staged conferences, some for researchers and others for a broad audience that encompassed corporate and government employees—including from General Motors, Bell Laboratories, Anaheim Police Department, and the US House of Representatives. Branded as Harvard Computer Graphics Week, this renowned five-day conference occurred annually between 1978 and 1983, drawing up to 500 participants its final year.14

Highlighting Harvard Computer Graphics Week’s disciplinary breadth, a program for the 1981 session noted that participants would learn “how computer graphics is being used to solve problems in corporate planning and management, marketing, energy exploration and distribution, physical design, natural resource management, city and regional planning, education, research, financial management, and many other areas.”15 And for those unable to attend this or other meetings, the LCG issued and sold the conference papers for all six years in the 19-volume publication Harvard Library of Computer Graphics.

Legacy

The LCG continued operation throughout the 1980s, albeit at a greatly reduced capacity due to shifting priorities and changes in GSD

leadership. The lab ultimately disbanded in 1991, leaving an impact that well exceeds its relatively brief existence.16 Through the development of cutting-edge software packages and a robust outreach program, the LCG introduced computer graphics and spatial analysis to a host of disciplines—including architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design. In addition, the lab acted as an incubator for innovation, providing “many of today’s essential ideas and early versions of tools now embedded in GIS [geographic information systems], remote sensing, geospatial science, geodesign, and online culture.17 Finally, the LCG served as a training ground for researchers who, following their time at the lab, went on to develop life-altering computer-based technologies. For example, the architectural software used throughout design professions today is grounded in the LCG’s work, as are four-dimensional holograms and digital mapping.

Among the LCG’s renowned former members are Jack and Laura Dangermond, then a GSD landscape architecture student and a social scientist, respectively. The Dangermonds spent a year in the late 1960s working in the LCG, which Jack recently described as “a place that shaped the rest of my life.”18 After Jack’s graduation from the GSD (MLA ’69), the Dangermonds returned to his hometown of Redlands, California, and cofounded the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri), building on their experience at the LCG. Today Esri is a global leader in GIS software, location intelligence, and digital mapping.

In 2015, Dangermond and other participants from the LCG’s heyday joined with contemporary researchers for a two-day conference entitled The Lab for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis and Its Legacy, organized to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the LCG’s founding.19 Mohsen Mostafavi, then GSD dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design, offered introductory remarks that situated the lab and its contributions as “part and parcel of our history.”20 This holds true not only for the GSD, where spatial mapping software is the cornerstone of many research studios, but for daily life in general. As we navigate city streets with the digital maps on our phones or learn about election results in precinct-by-precinct detail, we rely on LCG-derived technologies. As Mostafavi suggested, far from a bygone entity, the LCG endures as “a vision for the future.”21

*Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Special Collections, Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design.

- Leonard J. Currie, “Digest of the Career and Achievements of Howard T. Fisher,” sponsorship letter for Fisher AIA Fellowship application, c. 1974, https://web.archive.org/web/20150105113516/http://public.aia.org/sites/hdoaa/wiki/AIA%20scans/F-H/Fisher_Howard.pdf. ↩︎

- Nick Chrisman, Charting the Unknown: How Computer Mapping at Harvard Became GIS (Redlands, CA: ESRI Press, 2006), 20. For a detailed discussion of SYMAP, see chapter 2. ↩︎

- Evangelos Kotsioris, “The Computer Misfits: The Rise and Fall of the Pioneering Laboratory for Computer Graphics,” in Radical Pedagogies, eds. Beatriz Colomina et al. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022). An excerpt of this article appears in The MIT Press Reader, https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-computer-misfits-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-pioneering-laboratory-for-computer-graphics/. ↩︎

- Carl Steinitz, “The Beginnings of Geographical Information Systems: A Personal Historical Perspective,” Planning Perspectives 29, no. 2 (2014): 239–254, doi:10.1080/02665433.2013.860762. ↩︎

- A recent MoMA show, Emerging Ecologies, included a four-dimensional model derived from SYMAP’s output as an example of a pioneering approach to visualizing complex data about the environment. See Carson Chan and Matthew Wagstaffe, Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism (New York: MoMA, 2023), 70–71. ↩︎

- Ford Foundation, The Ford Foundation Annual Report 1966 (New York, NY: Ford Foundation, 1966), mission statement, https://www.fordfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/1966-annual-report.pdf. ↩︎

- Matthew W. Wilson, “Celebrating the Advent of Digital Mapping,” ArcNews, Esri, Winter 2015, https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcnews/celebrating-the-advent-of-digital-mapping/. Chrisman’s summarization of the LCG’s founding provides a slightly different ordering of events. See Chrisman, Charting the Unknown, 3. ↩︎

- Ford Foundation, Annual Report 1966, 7. ↩︎

- Chrisman, Charting the Unknown, 10–11. ↩︎

- Carl Steinitz, “Meaning and the Congruence of Urban Form and Activity,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 34, no. 4 (July 1968): 223–247. ↩︎

- Steinitz, “Beginnings of Geographical Information Systems.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Chrisman, Charting the Unknown, 158. ↩︎

- Harvard GSD Lab for Computer Graphics, brochure for Harvard Computer Graphics Week ’81, July 26-31, 1981, https://www.vasulka.org/archive/ExhTWO/Harvard/general.pdf. ↩︎

- The author thanks Martin Bechthold, Bruce Boucek, Stephen Erwin, Carl Steinitz, and Charles Waldheim for their willingness to be interviewed about the lab and its legacy. For more on the lab’s last decade and dissolution, see Chrisman, Charting the Unknown, chapter 11. ↩︎

- Harvard Center for Geographic Analysis, The Lab for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis and its Legacy, conference program, April 30 through May 1, 2015, https://cga-download.hmdc.harvard.edu/publish_web/CGA_Conferences/2015_Lab_Legacy/2015_CGA_Conference_Program.pdf. ↩︎

- In a recent article, Jack Dangermond wrote about his formative time in the lab. See Jack Dangermond, “How the Geographic Information System May Help Make the World Better,” Forbes, Oct. 8, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/esri/2024/10/08/how-the-geographic-information-system-may-help-make-the-world-better/. ↩︎

- The conference was hosted by the Harvard Center for Geographic Analysis (CGA), established in 2006 to support the use of GIS in research and teaching across the university. As such, the CGA acts as a successor of sorts to the LCG. ↩︎

- Mohsen Mostafavi, “Welcome & Introduction,” talk at The Lab for Computer Graphic and Spatial Analysis and Its Legacy, April 30, 2015, https://vimeo.com/128158780?autoplay=1&muted=1&stream_id=Y2xpcHN8MTMxODA5NTR8aWQ6ZGVzY3xbXQ%3D%3D. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

Christine Mueller MArch ’00 Inagurated Humayun’s Tomb Site Museum

Christine Mueller MArch ’00 of vir.mueller architects inaugurated a project for the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Humayun’s Tomb Site Museum, on Monday, July 29, 2024, in New Dehli, India. This is the first contemporary museum in India to be designed and built on a World Heritage Site. “The Site Museum aims to enhance the visitor’s experience, provide an opportunity to host collections of Mughal art, architecture and culture, and become a model for other such facilities across the country.”

Peitong Chen MDes ’21, MArch ’21 Presented at Adobe MAX

Peitong Chen MDes ’21, MArch ’21 recently presented at Adobe MAX, the largest design conference in the U.S., to an audience of over 10,000 attendees. She showcased cutting-edge technology developed by her team, with award-winning actress Awkwafina using the tools to design her living room. The presentation received global media coverage, further amplifying the impact of her work across the design and tech industries.

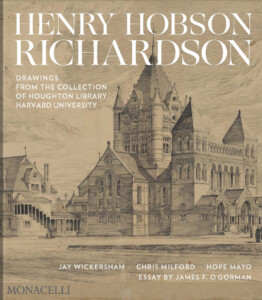

An Interview with Jay Wickersham: The Architecture and Legacy of H. H. Richardson

Foremost among nineteenth-century American architects stands H. H. Richardson. While most frequently associated with his Romanesque-inspired Trinity Church (1872–77) in Boston, Richardson’s reach extends far beyond this rusticated masonry masterpiece.

Richardson’s oeuvre, accomplished during a relatively brief life (he died at age 47), contains a wealth of remarkable buildings that creatively fuse varied inspirations—European and American, historical and contemporary, natural and technological. His work established a foundation for modern architecture and influenced succeeding generations of architects, including Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Furthermore, his collaborative studio served as a training ground for the many promising young architects, such as Charles McKim and Stanford White, who later joined William Mead to establish the firm of McKim, Mead & White; and George Shepley, who carried the mantle of Richardson’s studio after the older architect’s death.

By virtue of his education, social relationships, and built work, Richardson maintained deep connections with Harvard University. Now, with Monacelli’s release of Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University , an additional touchpoint between the architect and university comes to light. This new publication, coauthored by Jay Wickersham (MArch ’84), Chris Milford, and Hope Mayo, reveals the richness and breadth of Richardson’s studio’s work. In advance of the book’s launch , marked by an event at Harvard’s Lamont Library on October 29, 2024, the GSD’s Krista Sykes talked with Wickersham about his own connections to Harvard and how this ambitious book came to exist.

Wickersham first learned of Richardson as a Yale University undergraduate in the mid-1970s, through the courses and writings of historian Vincent Scully. By the mid-1980s, after completing his architectural studies at the GSD, Wickersham started making trips with his colleague and soon-to-be collaborator Chris Milford to the Massachusetts town of North Easton, home to five buildings that Richardson had designed for the Ames family a century prior. Meanwhile, Wickersham earned a law degree from Harvard and began practicing design, construction, environmental, and land use law. A few decades later, while Wickersham was teaching a course on the history of professional practice at the GSD, he and Milford became active in Richardson-related preservation efforts. They also ramped up their research, coauthoring an article together about the continuation of Richardson’s practice after his death. These endeavors set the stage for the current debut of Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library.

Krista Sykes: How did you decide to focus on Richardson’s drawings for this project?

Jay Wickersham: Through our earlier Richardson research and preservation work, we came to know Jim O’Gorman, the great expert on Richardson. In 2019, Jim suggested that we explore and publish, for the first time, Richardson’s archival drawings that are in Harvard’s Houghton Library. So Chris and I started working with our collaborator Hope Mayo. As the recently retired Philip Hofer Curator of Printing and Graphic Arts at Houghton Library, Hope was very familiar with the collection, and she brought a wealth of knowledge to our efforts.

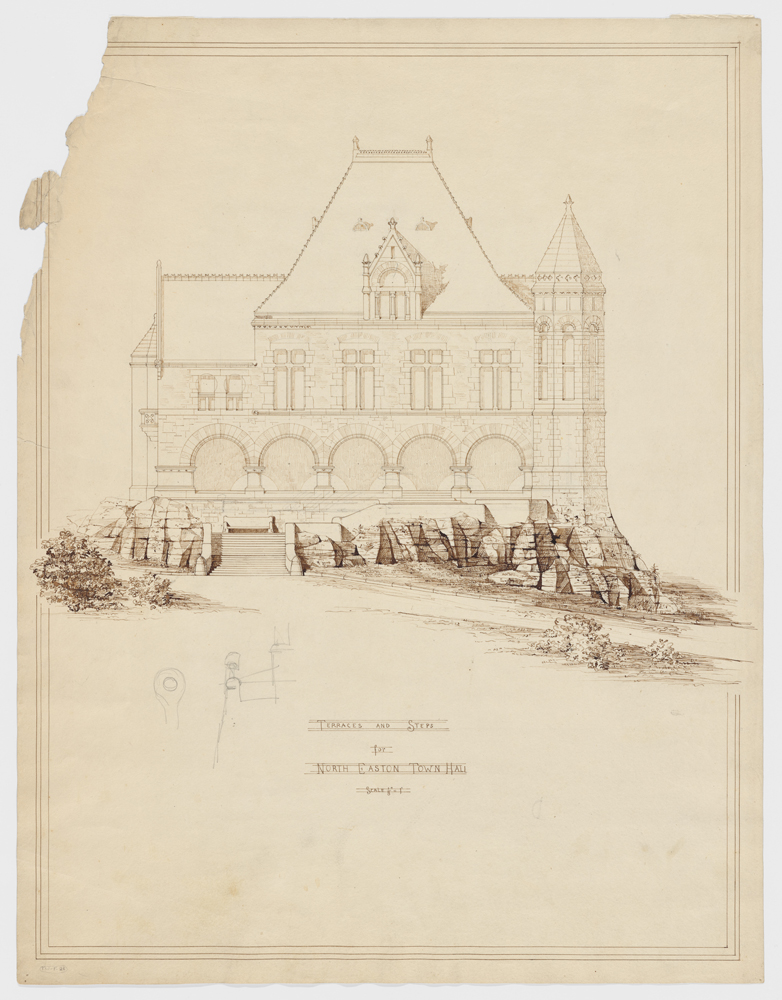

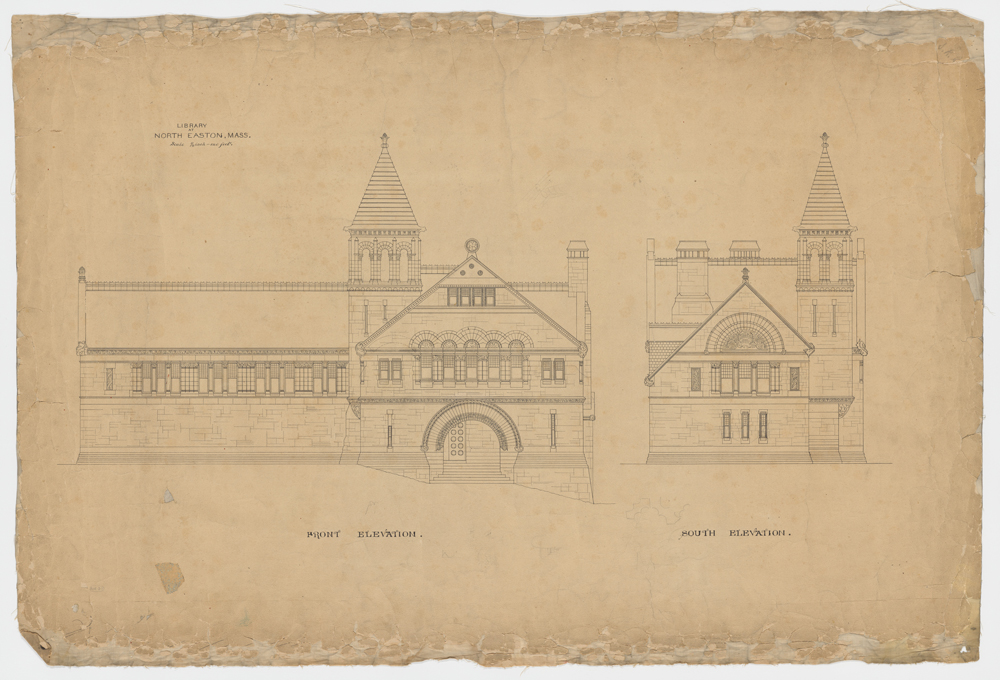

It took us five years to go through the full collection. We looked at every single drawing. There were over 4,000 drawings with more than 100 projects represented. The material had been roughly cataloged by project. Yet within each project, the drawings were only gathered by type—plan, section, elevation, perspective, detail, or site plan. No efforts had been made to organize them according to the process of the design, which we set out to do.

This task was rather challenging because almost none of the drawings are dated, signed, or even initialed. We had to work from the evidence of the drawings themselves, starting at one end, if there were initial sketches by Richardson, and then from the other end, thinking about what the completed building looked like, making inferences to link drawings of similar style, looking at how the design had likely evolved. What could the drawings tell us about the course of design?

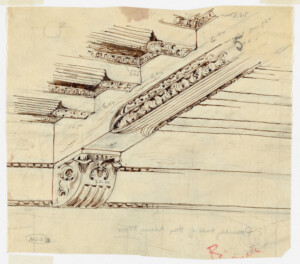

Furthermore, who made the drawings? Of the 4,000 drawings, only about 200 are from the hand of Richardson himself. In his collaborative studio, Richardson had a series of brilliant assistants, beginning with Charles McKim, followed by Stanford White, H. Langford Warren (who founded Harvard’s architecture program in 1893), Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow, and then the last two, Charles Coolidge and George Shepley, who continued the firm after Richardson’s death. We examined outside evidence alongside the drawings themselves, trying to identify the hands involved.

A Richardsonian building is so recognizable. We wondered, though—how did he retain this consistent design approach and yet, at the same time, give opportunities to his assistants? We came to think of Richardson’s studio like a performing arts group, the way that the Duke Ellington Orchestra over time reflects different flavors of its namesake’s music, depending on a succession of brilliant soloists and collaborators.

Indeed, much of what Richardson was able to do stemmed from his close relationship with his collaborators. The Norcross brothers from Worcester, Massachusetts, who created the first major national construction company, built most of Richardson’s great buildings. He trusted them to do the detailing, and he allowed them some freedom in carrying out the design intent. Then there was John Evans, who had a decorative carving studio in Boston. Richardson’s drawings showed indications of the subjects for a building’s decorative carving program, allowing the Evans studio to carry them out with individuality and flair.

So the atelier model on which Richardson based his studio extends to his collaborators as well?

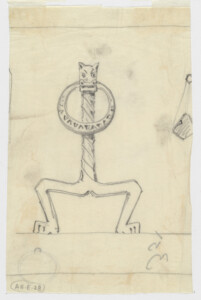

Very much so. He embraced the atelier model that Richardson experienced during his time at the École des Beaux-Arts. Yet he was equally imbued with the English Gothic Revival, with John Ruskin’s notion that decoration should derive from a building’s materials and methods of construction. Richardson also knew William Morris and his idea that the makers’ hands should be visible in the work. We view this as inherent with these collaborators, and even in the way that members of his studio could play with their own imagination in the buildings’ detailing. Our favorite element is for the Harvard Law School’s Austin Hall, where there are magnificent fireplaces in the classrooms. One day Richardson had a design charrette and asked everyone in the studio to design a set of andirons. There are 16 different andiron designs, each of them wonderfully playful. We’ve produced four of them in the book, another example of the richness that we’re trying to convey.

Could you say a bit about how you organized the material in the book?

In terms of essays, Jim has provided a framing article on Richardson’s biography, the large arc of his career, focusing on the design methods he learned at the École des Beaux-Arts. Chris and I have two essays: one is on the studio, how it operated, the key people within it, and the types of drawings it produced; the second is on Richardson’s clients and web of relationships, and his close friendships with Henry Adams and Frederick Law Olmsted, probably the two leading public intellectuals of post-Civil War America. Hope has written the first history of the archival collection, explaining its assemblage, how it got to Harvard, and all its diverse parts at Houghton and at the GSD’s Loeb Library. And for each building, we’ve provided a short introduction that outlines what to look for—a roadmap to the drawings.

With respect to drawings, the book highlights the scope of Richardson’s work, covered in a broad chronological arc from early to mid-period to late projects. And within that, we’ve organized it thematically, so you see how he tackled different building types and explored variations on a theme: major civic works, commercial office building, train stations, houses. Perhaps his greatest achievement is the series of five public libraries, where this new quintessentially democratic program is given a form that draws on European heritage and the American landscape. The extraordinary range and diversity in his work is something that we really wanted to convey.

How did Richardson’s archive come to Harvard?

Richardson was a Harvard undergraduate, class of 1859, and he later designed two major buildings for the campus—Sever Hall (1878–80) and Austin Hall (1880–84). Other people in the firm attended Harvard as well, and then the Shepley firm continued as the university’s architect up until the 1960s. But the firm kept the drawing collection in their own offices, which was in the Ames Building in downtown Boston.

Concerning the transfer of the archive to Harvard, there were two key events. First, after several decades of neglect, Richardson’s work gained renewed attention in the 1930s. Louis Mumford wrote about him in The Brown Decades of 1931, and then in 1936 Henry-Russell Hitchcock staged a show on Richardson at MoMA and published an accompanying monograph. These incidents brought Richardson back to prominence. And second, in 1942, Harvard opened Houghton Library, a state-of-the-art, climate-controlled library for rare books and manuscripts. So, the firm donated the entire collection of drawings to Houghton, where they have been ever since. They also gave over 50 albums of study photographs that the office had used for reference purposes, and Richardson’s surviving architectural library. The photo albums and the architectural library are at the Loeb Special Collections at the GSD.

There’s so much material in Richardson’s archive. How did you and your co-authors tackle it?

First, we consulted with Jim and did an initial pass. Then we started with the most prominent buildings that were the best documented and went back to fill in the additional ones. We also looked at high-quality reproductions of presentation drawings that Richardson’s office had made. Having done that, we did a rough cut for each building with two to three times the images we knew we could include. We then winnowed those down to our final cuts.

Next, we worked with the library to produce high-quality, full-color digital images of the selected drawings. In all, they account for just over 10 percent of the archive; about 450 drawings are in the book, plus several archival photographs. Those now exist as high-grade digital images for future scholars, who can use the book as a guide for going back into the archive.

Throughout the creation of the book, did anything stand out as a welcome surprise?

We’re quite happy that, through the design and reproduction process, the tactile quality of these fragile archival documents was retained. You can see the irregularities, the stains and creases and tears in the drawings, the different colors of background paper. The images allow you to see the designs themselves while still conveying the sense of these drawings as physical objects.

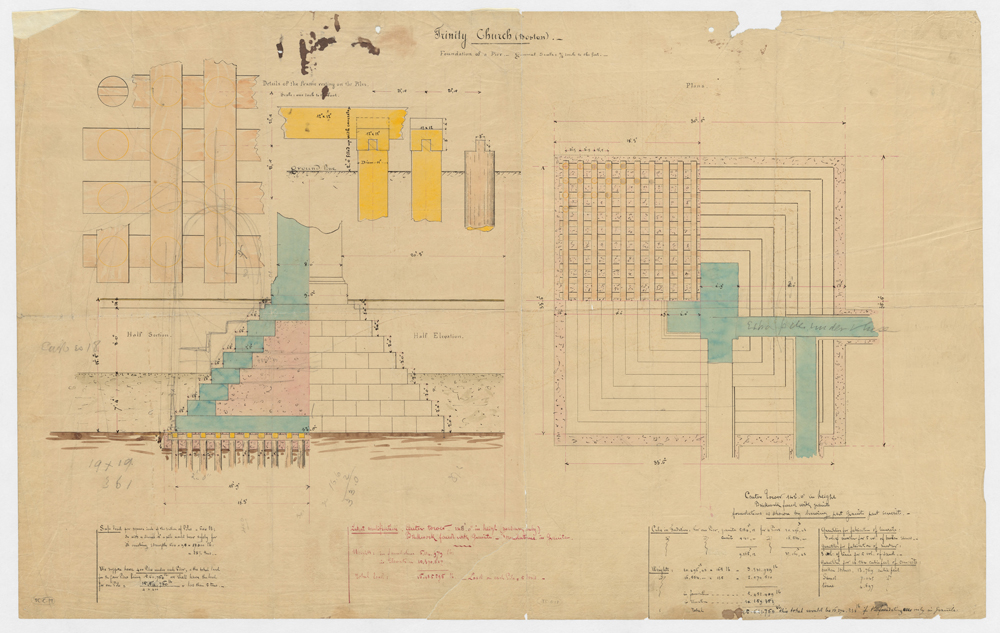

It was also fascinating to see the quality of the drawings, particularly when we got to the working drawings. They’re ink on vellum, with a soft watercolor wash on the back of the vellum to indicate materials—so gray for stone, pink for masonry, yellow for wood. The working drawings are in themselves very beautiful graphically.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Richardson no doubt saw his share of changing circumstances in terms of cultural shifts, scientific development, and more.

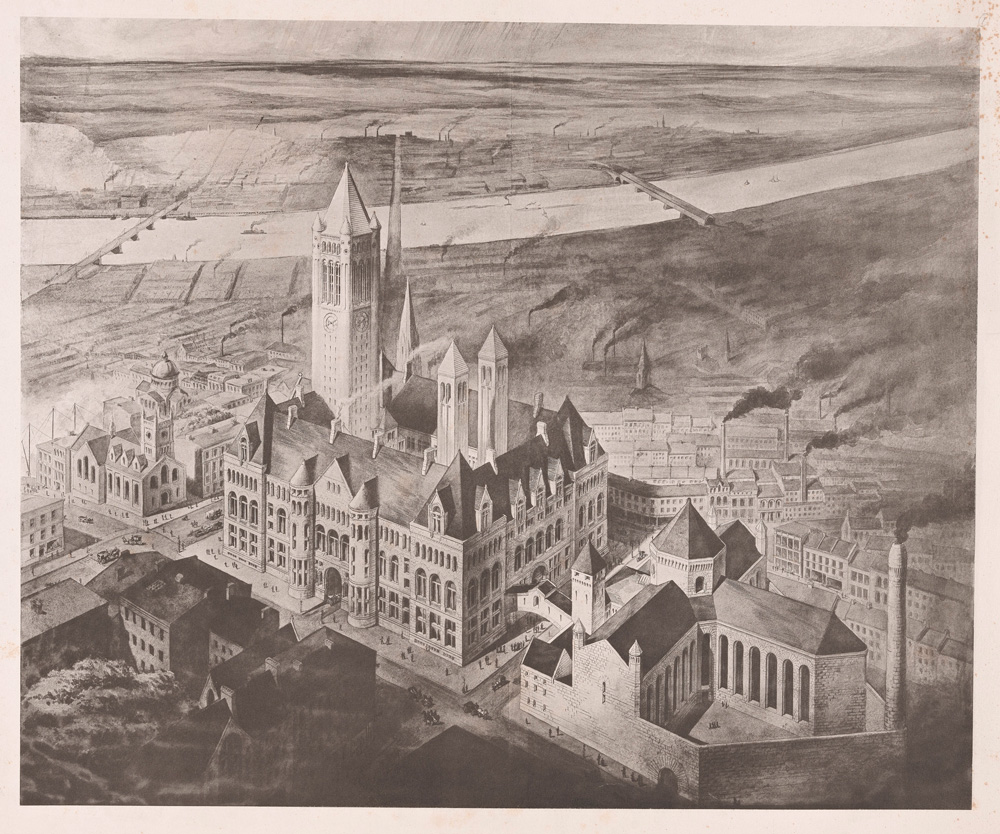

Oh, certainly. In fact, Richardson and the studio were very attuned to the latest technological innovations. The idea that he was just a masonry architect who was not technologically enterprising is a real misapprehension. In the drawings we found a lot of evidence to the contrary, and we tried to convey this in the book. You’ll see that we’ve included a remarkable bird’s-eye perspective of the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail set in the degraded environment of Pittsburgh, showing the surrounding smoking chimneys and the cloud of air pollution enveloping the city. With this image, you understand the complex’s big central tower provided clean, purified air for the building. It was intended to be tall enough to bring in fresh air, which was drawn down by large fans into the basement, filtered, humidified, and then conducted up through ducts in the walls into the courtrooms and the offices.

Before we conclude, could you summarize the overarching goals that guided you and your coauthors through the book’s creation?

First, we saw Richardson’s work as a window into the act of design, underscoring how design is not, as architects know, a linear process. This is at the heart of the book. Also, we hoped to dispel the idea of Richardson—or any great architect—as a lone figure. Architecture is made collaboratively, which becomes clear as we talk about Richardson’s studio as well as the connections with people like the Norcross brothers and Evans. Maybe the third idea relates to back in the 1930s when Mumford and Hitchcock helped rediscover Richardson’s work, and then more recently, Scully and O’Gorman. Richardson has been a source of revitalization for architecture at various points, and we hope there will be new ways in which he can provide inspiration going forward.

*Unless otherwise noted, illustrations are courtesy of the H. H. Richardson Drawings Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Structural Design I

This course introduces students to the analysis and design of structural systems. The fundamental principles of statics, structural loads, and rigid body equilibrium are considered first. The course continues with the analysis and design of cables, columns, beams, and trusses. The structural design of steel follows, culminating in the consideration of building systems design. The quantitative understanding of interior forces, bending moments, stresses, and deformations are an integral part of the learning process throughout the course. Students are expected to have completed all prerequisites in math and physics.

Objectives:

- Provide an understanding of the behavior of structural systems

- Introduce basic structural engineering concepts and simple calculations applicable in the early stages of the design process in order to select and size the most appropriate structural systems

- Teach the engineering language in an effort to improve communication with design colleagues

Topics:

- Statics (equilibrium of loads and force reactions)

- Load Modeling (load types, flow of force, and load calculations)

- Interior Forces (axial, shear, and bending moment diagrams)

- Mechanics of Materials (stress, strain, elasticity, thermal considerations)

- Analysis and Design of Columns (slender v. compact column design)

- Analysis and Design of Hanging Cables

- Analysis and Design of Arches (funicularity)

- Analysis and Design of 2D Trusses (method of joints, method of sections)

- Analysis and Design of Beams (flexural stress, cross-sectional properties)

- Steel Design (allowable stress design, ultimate limit state design, yield stress)

- Building System Design

We will be placing a copy of “Structures” (7th Edition): Daniel Schodek, Martin Bechthold on reserve in the Loeb Library. This text is NOT a course requirement but will be on reserve as a reference for those seeking additional background information on course topics.