Love in a Mist: The Politics of Fertility

Love in a Mist: The Politics of Fertility explores several evolving narratives on the spaces and politics of fertility, triggered by the “heartbeat bill,” which recently passed into law in states such as Mississippi, Kentucky, and Georgia to criminalize abortions from as early as six weeks into pregnancy.

The exhibition explores society’s quest to control women and nature, and the resulting environmental degradation. It brings together issues such as the historical use of synthetic hormones in women’s bodies; measures to super-size farm animals and domesticate plants; and techniques to accelerate fertility and extract natural resources.

From the treatment of women’s bodies to the exploitative human relationship with nature, Love in a Mist examines spaces of fertility including abortion clinics, artificial wombs, court rooms, farmed landscapes, and swamps, as extrapolated from diverse accounts and imaginaries by scholars, activists, legislators, ecologists, biologists, artists, and designers.

Excerpt 1: Reproductive Rights

From antiquity until the Renaissance, women cultivated a relationship with the natural world. The intimate knowledge of plants, medicinal herbs in particular, was passed down to enable future generations of women “to regulate fertility” and “function with some measure of independence in respect to reproduction” (John M. Riddle). From the 13th century on, however, women’s control over their bodies and reproductive knowledge has been increasingly criminalized. Women have been punished and terrorized, their bodies burned, and their teachings obliterated through church-led inquisitions and in civil courts. The pursuit to govern reproductive know-how and rights with impunity is an attack on practices of care, women’s rights, health, socio-economic freedom, and knowledge itself.

In the United States today, new compounded efforts by pro-life activists to criminalize abortions and prevent women from having access to reproductive health care are being backed by the federal government and legislators. In 2011, there was one attempt to outlaw abortions in Ohio; in 2019, there were 39—including moves to pass the heartbeat bill in Missouri, South Carolina, Kentucky, Florida, Mississippi, Minnesota, Tennessee, Maryland, Texas, West Virginia, New York, Ohio, Illinois, Georgia, Louisiana, and Michigan.

For some foundation, the United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 2542 in 1969, proclaiming the Declaration on Social Progress and Human Rights, which states:

All couples and individuals have the basic right to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children and to have the information, education and means to do so; the responsibility of couples and individuals in the exercise of this right takes into account the needs of their living and future children, and their responsibilities toward the community.

In 1973, U.S. Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade affirmed that access to safe and legal abortion is a constitutional right.

While the pro-life movement promotes the heartbeat bill, the Trump administration has nominated over 150 conservative federal judges and two Supreme Court justices, gaining further support for these measures. And as of March 4th, 2020, Title X, which has provided federal funding for family planning and women’s health clinics throughout the country since 1970, will be under “Gag Rule,” effectively curtailing aid to women:

Clinics that receive funds from the federal family-planning grant program Title X will no longer be able to perform abortions in the same space where they see other patients. Abortion and other health-care services will be required to be physically and financially separate entities. Title X participants will also no longer be able to refer patients to abortion providers, though they can mention abortion to their patients. (Planned Parenthood report)

The intrinsic connection between spatial design and human rights reconfigures the spatial typology of women’s health and family planning clinics, the report continues: “about 20 percent of Title X providers would potentially have to renovate their clinics to meet the new guidelines. . . . It will likely cost each of these providers $20,000 to $40,000 to come into compliance with the physical-separation element of the new rule.”

Excerpt 2: Accelerated Growth

During and after the world wars, hormones and fertilizers were being developed to increase reproduction of resources and accelerate growth in the natural world. Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthetic form of the hormone estrogen—important to reproduction especially in women—was discovered in 1938. Just a few years later doctors began prescribing it to pregnant women as a dietary supplement that could prevent pregnancy-related complications including miscarriage and premature labor. In 1947, Harvard University physician and biochemist George Smith and endocrinologist Olive Smith published studies linking the use of DES in high doses to miscarriage prevention. Their studies were used by drug company representatives to convince doctors to prescribe DES to pregnant women (DES Action USA).

In the agricultural world, DES was used as a growth hormone to improve the ratio of feed to desired weight in livestock. Three decades on, however, empirical studies linked the hormone directly to increased breast cancer among the over 4.8 million women prescribed DES, cervical and vaginal cancer in their daughters, and congenital disabilities and deformation in their children generally. Its use in intensive livestock farming gradually led to the contamination of land, water, plants, and consequently also other living species (Paola Ebron and Anna Tsing). In 1971, the FDA issued a Drug Bulletin to physicians, stating that DES is contra-indicated for use in pregnant women. The FDA did not ban DES, but only urged doctors to stop prescribing it for their pregnant patients (DES Action USA).

Excerpt 3: Extinction

On May 6, 2019, the UN released a report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, warning that nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history. The pace of species extinction is accelerating, gravely impacting people across the world. The report emphasizes the need to improve and strengthen practices of care between humans and the natural world by recognizing the positive contributions of women, and indigenous communities in particular, to nurturing human relations with the environment and to regenerative sustainability. It recommends incorporating indigenous wisdom, values, and technology into conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of land and resources, as well as including indigenous peoples, women, and local communities in environmental governance.

Excerpt 4: Compost

The final part of the exhibition is a homage to Donna Haraway’s “Children of Compost” fabulation and her plea to reimagine a different relation between humans, the Earth, and other living entities. The shared fate of human and non-human life on Earth in this time of environmental destruction and social injustice requires joining forces across disciplines, old wisdom and contemporary knowledge, cultures and species, to decenter the human and reimagine symbiotic living and sustainable and equitable futures.

Love in a Mist is installed inside four consecutive greenhouse structures, at turns exposed and covered by mesh textile. Each greenhouse hosts a set of artworks. Together, they extrapolate multiple narratives that can be read as “snapshots,” capturing brief episodes in the history of the politics and spaces of fertility from Reproductive Rights to Accelerated Growth, and Extinction to Compost.

The Reproductive Rights structure houses Women on Waves’ mobile treatment room, which provides access to safe abortions at sea, and a campaign with its online sister organization Women on Web that flies drones with abortion pills from women in one country to women in another. The inclusion of Diana Whitten’s film provides an engaging history of their work. Next, Lori Brown’s Don’t Mess with Texas considers the state’s vehement antiabortion stance in an essay and maps. Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST) underscores the extent of this condition throughout the United States in archival material about violence against abortion clinics, reproductive rights legislation, and ancient abortifacient potions. Displayed as a series of broadsheet-sized tabloids, the collection is accompanied by an illustration of how the recent “heartbeat bill”—criminalizing abortions from as early as six weeks into pregnancy—has spread across the country.

The works within Accelerated Growth, a partly covered greenhouse, explore the genealogy of synthetic hormones and their impact on women, farmed animals, land, and bodies of water. FAST’s inflatable installation Bodies of Steroids stands in parallel to Bernie Krause’s recordings of diminishing soundscapes in nature.

Extinction begins with UNCERTAIN, TX and Complex Systems by Desirée Dolron, the first conveying the deterioration of Caddo Lake State Park, Texas in looping images, and the second evoking the sensitivity of group relations. Bringing scientific backing to this claim, the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services report from May 2019 is made available to show empirical studies on diminishing biodiversity and mass extinction of species worldwide. The document, which also proposes actions across governments, cities, communities, and households, is situated next to an indigenous call for action: Inuit Knowledge and Climate Change directed by Zacharias Kunuk and Ian Mauro.

The Compost greenhouse is inspired by Donna Haraway’s book Staying with the Trouble. The works weave together speculative imaginaries by artists examining women’s bodies, minds, and relations to the natural world from different perspectives—political, biological, spiritual. Yael Bartana’s trailer and neon work What If Women Ruled the World?, “brings some of the world’s best strategic minds together to help avert impending disaster while situated in a replica of Dr. Strangelove’s War Room.” Tabita Rezaire’s video Sugar Walls Teardom pays tribute to the imposed contribution of black womxn’s wombs to medical science. The artist’s treatment of their eternal healing power is shared in the closing work titled Womb, a sculpture by Atelier van Lieshout that offers “a stylized representation of the interior of the human body, almost perfect anatomical renditions of the organs that keep us going.”

Love in a Mist: The Politics of Fertility is curated by Malkit Shoshan, Area Head of the Master in Design Studies program’s Art, Design, and the Public Domain (ADPD) concentration, and founding director of the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST), an Amsterdam- and New York-based think-tank that develops projects and campaigns at the intersection of architecture, urban planning, design, and human rights.

Artworks and Projects on View in Love in a Mist

1) Women on Waves, A Portable Abortion Clinic, 2001, installation

Women on Waves sail a ship to countries where abortion is illegal, so that early medical abortions can be provided safely, professionally, and legally. National penal legislation, and thus also of abortion law, extends only to territorial waters; outside that 12-mile radius Dutch law applies, rendering Women on Waves’ activities legal. Millions of women worldwide have used mifepristone and misoprostol to terminate pregnancy with impressive safety and efficacy. The medicines have been on the World Health Organization (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines since 2005. Women on Waves has already created enormous public interest in its efforts and completed successful campaigns in Mexico (2017), Guatemala (2017), Morocco (2012), Spain (2008), Portugal (2004), Poland (2003), and Ireland (2001). Women on Waves’ mobile treatment room, designed by artist Joep van Lieshout and funded by Mondriaan Fund, was first presented in Play-use, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, in 2000, appearing the following year in the 49th Venice Biennale and various art magazines.

2) Women on Web, Abortion Drones, 2019, installation

The drones flies abortion pills from one country to women in another. Drawing attention to differing regulations, women’s realities in countries where abortion is restricted are made visible by creating access.

3) Vessel, written and directed by Diana Whitten, 2014, film

This documentary film written and directed by Diana Whitten on the work of Women on Waves, a Dutch pro-choice organization founded by Dutch physician Rebecca Gomperts in 1999, follows Gomperts as she sails a ship around the world and provides abortions at sea for women who have no legal alternative. She trains women to give themselves abortions using WHO-researched protocols with pills and creates an underground network of empowered activists who trust women to handle abortion themselves. The film’s world premiere took place at SXSW in Texas on March 9th, 2014 and is distributed by FilmBuff since 2015.

4) Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST), reproductive rights and the heartbeat bill, 2019, informative papers and diagrams

Selection of news items, legislation, and information about reproductive rights and access to safe abortions in the US are packaged as a series of diagrams and broadsheet-sized tabloid handouts.

5) Lori Brown, Don’t Mess with Texas, 2018, essay and maps

Texas is willing to drastically limit women’s access to reproductive health care with little to no regard for the consequences for millions of women. The state’s antiabortion policies have been copied by Missouri and Iowa, and the Trump administration is working to expand similar policies internationally by refusing to provide American aid to any international organization that discusses abortion. Many other states are following their lead. Texas serves as a frightening wake-up call to the rest of the country on so many levels: high rates of poverty, incarceration, immigration, and deportation—and extremely progun rights. Its assault on social services and reproductive health care leaves many women with little choice but to travel long distances to access abortion services. Should the situation continue, it will go from very bad to much worse.

6) Bernie Krause, Lincoln Meadow at Yuba Pass, California, geophony sound

Dates: June, 1988 and 1999

Location: 39°35’29.26”N/120°30’02.53”W

Habitat: Sub-tropical forest

Season: Spring

Climate: Sub-tropical coastal rainforest

Weather: Clear/partly cloudy (80.6°F)

About a three-and-a-half hour drive east of San Francisco, at an altitude of nearly 7,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada mountains, is a spectacular sub-alpine meadow surrounded by ponderosa pine, juniper, and lodgepole pine trees with a clear mountain stream bisecting the habitat. When I first began recording there in the early 1980s, the site was an old-growth habitat that, while accessible to hikers and skiers, had not undergone any significant changes over time. Then, in 1988, a logging company convinced local residents that a new tree-cutting protocol they were using, called selective logging (taking out a tree every 65 feet or so—rather than cutting down everything in sight), would have no negative impact on the environment. While the local residents accepted their explanation, I remained skeptical and asked the company representatives if I might record at the site before and after their activity. Permission granted, I recorded the dawn chorus in mid-June of 1988, before logging later that summer, and, again in 1989, a year after the company’s action. To the human eye and any frame of a camera, the site appeared as if there had been no change. That observation, by itself, would have supported the logging company’s claim that there was no environmental impact from their activity. However, the difference to both the ear supported by a visual image of the sound in the form of spectrograms is clear. In the 1988 example, the signature of the mountain stream can be seen in the lowest third of the image while the bird vocalizations are visible in the middle third. They typically include, mountain quail, red-breasted and Williamson’s sapsuckers, Townsend’s solitaire, Cassin’s finch, western wood-pewee, Hammond’s flycatcher, hermit and MacGillivray’s warblers, western tanager, Lincoln sparrow, white-crowned sparrow, and the green-tailed towhee. In the 1989 sample, the birdsong density and diversity was all but gone, with only the sound of the stream and a Williamson’s sapsucker (woodpecker) present in the soundscape and spectrogram. Despite 15 visits over the past 27 years, the biophony in this fragile habitat has not yet returned to its pre-1988 level.

7) Bernie Krause, Sugarloaf State Park, Kenwood, California, geophony sound

Dates: April 15, 2004, 2009, 2014, and 2015

Location: 38°26’20.05”N/122°29’56.06”W

Habitat: Oak chaparral/low scrub vegetation: Baccharis pilularis

Season: Spring

Climate: Temperate

Weather: Clear (avg. 40°F)

In our area, about 50 miles north of San Francisco in an area known as Jack London’s “Valley of the Moon,” there was no birdsong during the spring and summer of 2015. None whatsoever. There were birds, to be sure. And they sometimes called. But there was no singing, per se. It was the first time in my seventy-seven years that I can ever remember not hearing birds sing in the morning at sunrise during spring and summer. Sugarloaf Ridge State Park is about a twenty-minute drive from our home, a combination of scrub vegetation, different kinds of oak trees, and alders; it is located in a separate valley that cuts through the floor of the park and is bisected by a winter stream. Nestled in the Mayacamas Mountains separating Sonoma and Napa Valleys, both famous for fine California wine, the spring cycle and warmer days have occurred progressively earlier with each passing year—about 2 weeks earlier than when I began to record there in the early 90s; vegetation leafs out sooner, the temporal distribution of precipitation has shifted, and the migrating patterns of birds, once represented by a fairly constant density and diversity, have changed. There has been a dramatic swing in the mix of dominant species in my recordings since the early 1990s. While the combination in our region was pretty constant—within a certain dynamic expectation at the outset—new species of birds appear with each season since the early 2000s, while the expected ones have diminished in number, or have disappeared altogether, as confirmed by annual systematic bioacoustic sampling.

The presentation is divided into 4, 15-second soundscape samples within 48 hours of April 15 in 2004, 2009, 2014, and, finally, 2015, calibrated to within 1/10th of a dB with the same protocols rigorously observed over the 11-year period. The bottom third of the spectrogram features the acoustic signature of a nearby stream, running fully charged in the first two segments, but almost silent in the third because of the drought. In the fourth, because the drought was so severe, there is no stream to be seen or heard. The middle third of the spectrogram, just above the stream signature, is a biophony comprised of birdsong from dark-eyed juncos, golden-crowned and white-crowned sparrows, California towhees, acorn woodpeckers, black-headed grosbeaks, American robins, Brewer’s sparrows, red-shouldered hawks, pileated woodpeckers, and wild turkeys. Note the subtle density reduction in birdsong between 2004 and 2009, and the almost complete lack of density and diversity in 2014 and 2015, with the full impact of the drought.

8) Bernie Krause, Spread Creek Pond, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, geophony sound

Dates: June 15, 1981 (5am) and June 26, 2009 (5:23am)

Location: 43°45’50.08”N/110°31’16.88”W

Habitat: Marsh, Great Basin coniferous

Season: Spring

Climate: Temperate

Weather: Clear (avg. 35°F)

Spread Creek Pond lies about 25 miles northeast of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, not far from the magnificent Grand Teton National Park. This signature habitat is being affected by global warming in a way that is expressed through the narrative of the biophony. In 1981, when I recorded the first digital natural soundscape recording (using a primitive and awkward Sony F1 beta device) as heard in the first example, the birds present were warbling vireo, yellow warbler, white-crowned sparrow, Wilson’s warbler, house wren, and dusky flycatchers. By 2009, as shown in example number 2, spring was arriving in that biome about 2 weeks earlier, enough to alter the landscape so that the vegetation was leafing out earlier, the precipitation was a bit drier, and the entire mix of birds had changed. Both the density (of birds) and diversity (of species) now featured the hermit thrush, Swainson’s thrush, cowbird, grosbeak, yellow-rumped warbler, dark-eyed junco, chipping sparrow, and white-crowned sparrow—a nearly complete change of characters than had previously remained constant for many, many years.

9) Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST), Bodies of Steroids, 2019, inflatable

10) Desirée Dolron, UNCERTAIN, TX, 2016, video

The viewer’s eye slowly moves across a morass of secular cypress trees, swathed in Spanish moss, immersed in water. Under the surface, a foreign weed is rampant and disturbing the local ecosystem. The succession of images in loop and the suffocating sound of the audio accentuate the impression of the forest’s continuous deterioration. The title is taken from the name of the town in Texas where I stayed during production. It also refers to the future of the trees and, in a broader sense, to the fragility of life in general.

11) Yael Bartana, What If Women Ruled the World?, 2016, neon and trailer

“It is two and a half minutes to midnight, the clock is ticking, global danger looms. Wise public officials should act immediately, guiding humanity away from the brink. If they do not, wise citizens must step forward and lead the way” (The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists). Arriving at a moment of unprecedented worldwide flux, Yael Bartana’s performative project What If Women Ruled the World? brings some of the world’s best strategic minds together to help avert impending disaster. The experiment uses a fictional scenario to examine real-life issues. Each night, a group of actors playing the female government of a fictional country meet with a group of international female experts in a replica of Dr. Strangelove’s War Room: defense advisers, soldiers, peace activists, humanitarians, politicians, and leading thinkers. Together they will spend the evening attempting to solve the global emergency, and stop the Doomsday Clock from reaching midnight.

12) Tabita Rezaire, Sugar Walls Teardom, 2016, video

Sugar Walls Teardom reveals the contributions of Black womxn’s wombs to the advancement of modern medical science and technology. During slavery, Black womxn’s bodies were used and abused as commodities for laborious work in plantations, sexual slavery, reproductive exploitation, and medical experiments. Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy, were among the captive guinea pigs of Dr. Marion Sims—the so-called “father of modern gynecology”—who tortured countless enslaved womxn in the name of science. Unacknowledged, Black womxn’s wombs have been central to the biomedical economy as the story of Henrietta Lack—whose stolen cervix cells became the first immortal cells leading to medical breakthrough—reminds us. Biological warfare against Black womxn is still pervasive in today’s pharmaceutical industry. Sugar Walls Teardom celebrates womb technology through an account of coercive anatomic politics and pays homage to these wombs; their contributions have not been forgotten.

13) Atelier van Lieshout, Womb, 2000, sculpture

Womb (small) is part of a set of colorful fiberglass sculptures that Atelier Van Lieshout produced in the early 2000s: human figures in various postures and actions, but also a complete series of human internal organs, ranging from heart, brain, and liver to the rectum and female sex organs. These works are a stylized representation of the interior of the human body, almost perfect anatomical renditions of the organs that keep us going. Womb was created in a series of wombs including the functional sculpture Wombhouse, now in the collection of the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

14) Desirée Dolron, Complex Systems, 2016, video

Complex Systems displays a digitally drawn flock of starlings scattering across the sky in a loop of ever-changing patterns. In this work themes such as the fragility of existence, impermanence, and the dichotomy between the individual and the collective form the conceptual ground of the artist’s inquiry. The title is adopted from the scientific field of network research, which employs the term to define the complex interactions between different components of the same group. The shapes assumed by the birds are proven to be the result of a defense mechanism system: in order to avoid attack by predators, a singular starling keeps track of seven others simultaneously—in doing so, the starling is able to adapt to the changing flying directions of the entire flock, thus keeping the collective intact. The dichotomy between the individual and the collective is at the core of Dolron’s interest in this natural phenomenon. Complex Systems investigates the relation between singular and shared intelligence, prompting questions concerning humanity, the psyche, and the possible presence of a collective unconscious. The link to the human psyche is emphasized by the cyclical character of the film; Dolron underlines the full turn of life in which the starlings function as a metaphor. Their movements change from an initial drive to a final slow fall, while the murmuration happens in an eternal loop that symbolizes the cycle of life and its fragility. The movements of the starlings, combined with the pivotal soundtrack of murmuring voices that intensify and fade according to the flock’s movements, allude to the human mind in a state of constant flux.

The above descriptions are lightly edited versions of previously published material by the artists.

All photography courtesy Justin Knight

Exhibition Credits

Curator, research, and exhibition design: Malkit Shoshan

Participating activists, artists, and designers: Atelier van Lieshout, Yael Bartana, Lori Brown, Desirée Dolron, Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST), Rebecca Gomperts, Bernie Krause, Tabita Rezaire, Women on Waves, Women on Web, Diana Whitten

Graphic design: Sandra Kassenaar

Copy editor: Janine Armin

Research assistant: Carolina Sepúlveda

Exhibition production: Dan Borelli, David Zimmerman-Stuart

Exhibition installation: Ray Coffey, Jef Czekaj, Anita Kan, Sarah Lubin, Jesús Matheus, Joanna Vouriotis

Production assistant: Inés Benítez Gómez

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Mohsen Mostafavi, Rebecca Gomperts, Krzysztof Wodiczko, and Matthijs Bouw for the invitation, inspiration, and support.

Yael Bartana, Dan Borelli, Lori Brown, Ray Coffey, Jef Czekaj, Desirée Dolron, Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson, Jennifer Hamilton, Inés Benítez Gómez, Anita Kan, Sandra Kassenaar, Bernie Krause, Joep van Lieshout, Sarah Lubin, Jesús Matheus, Astrida Neimanis, Tabita Rezaire, Carolina Sepúlveda, Diana Whitten, Joanna Vouriotis, and David Zimmerman-Stuart for your generous contributions to the exhibition.

The books, essays, lectures, and activism of Barbara Ehrenreich, Deirdre English, Silvia Federici, Donna Haraway, Ann Hibner Koblitz, John M. Riddle, Our Bodies Ourselves, Carolyn Merchant, María Puig de la Bellacasa, and Anna Tsing inspired and laid the intellectual foundation for this exhibition.

Love in a Mist: The Politics of Fertility is generously supported by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York as part of the Dutch Culture USA program.

Artist & Contributor Biographies

Atelier van Lieshout was founded by the sculptor Joep van Lieshout in 1995 in Rotterdam. The company create and fabricate widely exhibited works. The name emphasizes the fact that although the sculptor founded and leads the studio, the work produced stems from the creative impulses of the entire team. Recurring themes in the work include self-sufficiency, power, politics, and the more classical life and death.

Yael Bartana is a video artist who explores the imagery of cultural identity. In her photographs, films, and installations Bartana critically investigates her native country Israel’s struggle for identity. Her early work documents collective rituals introducing alienation effects such as slow-motion and sound. In her recent work the artist stages situations and introduces fictive moments into real existing narratives.

Lori Brown is co-founder of ArchiteXX, a group dedicated to transforming the architecture profession for women. She is a registered architect, an author, and associate professor at Syracuse University. Her research focuses on architecture and social justice issues with particular emphasis on gender and its impact upon spatial relationships.

Desirée Dolron is a Dutch photographer who lives and works in Amsterdam. Her photographs portray a variety of styles and subjects involving documentary, still lifes, portraits, and architecture.

Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST) is an Amsterdam- and New York-based think-tank that develops projects and campaigns at the intersection of architecture, urban planning, design, and human rights.

Rebecca Gomperts is a doctor based in Amsterdam and founder of Women on Waves and Women on Web, which provide reproductive health services for women in countries where it is not provided. In 2013 and 2014, she was included in the BBC’s 100 Women. In 2018, she founded Aid Access, which operates in the US. A trained abortion specialist and activist, she is generally considered the first abortion rights activist to cross international borders.

Bernie Krause is an American musician and soundscape ecologist. In 1968, he founded Wild Sanctuary, an organization dedicated to the recording and archiving of natural soundscapes. Krause is an author, a bio-acoustician, a speaker, and natural sound artist who coined the terms geophony, biophony, and anthropophony, and, as a founder of the field, was germane to the definition and structure of soundscape ecology. Krause holds a PhD in Creative (Sound) Arts with an internship in bioacoustics from Union Institute & University in Cincinnati.

Tabita Rezaire is a French video artist, health-tech-politics practitioner, and Kemetic/Kundalini yoga teacher based in Cayenne, French Guyana. Her practices unearth the possibilities of decolonial healing through the politics of technology.

Malkit Shoshan is the founding director of the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST), an Amsterdam- and New York-based think-tank that develops projects and campaigns at the intersection of architecture, urban planning, design, and human rights. She is a researcher, author, and designer and the Area Head of Art, Design, and the Public Domain (ADPD) MDes at Harvard GSD.

Women on Waves is a Dutch pro-choice nongovernmental organization (NGO) created in 1999 by Dutch physician Rebecca Gomperts, in order to bring reproductive health services, particularly non-surgical abortion services and education, to women in countries with restrictive abortion laws.

Women on Web is the online sister organization of Women on Waves.

Shinohara Kazuo: ModernNext

For much of his career, Shinohara Kazuo built beautiful single-family houses that have reconfigured and enriched our understanding of domesticity, tradition, form, language, scale, nature, and the city. He famously declared “A house is a work of art” just as the Metabolists, who were his contemporaries, were ascending in influence and notoriety. While Shinohara organized his long career into a chronological series of Styles—First, Second, Third, and Fourth—through which he pursued different formal, representational, and technological expressions, there were also important motifs he never wavered from, with the relationship between the house and its surrounding urbanity being the most important and persistent. This exhibition on Shinohara’s architecture highlights his nuanced attitude toward the city, which emerged with greater saliency in the late 1970s and reached its apotheosis in the following decade through a series of institutional-scale projects. This position was partly informed by his travels abroad, to Africa, the Americas, and Europe, and by his reading of European cultural criticism. Shinohara labeled this last period the Fourth Style. In an essay published in the journal Kenchiku Bunka in 1988, Shinohara introduced the term “ModernNext.” As a counterpoint to postmodernism, ModernNext was also a commentary on Japan’s Bubble Economy, as the scale and intensity of urban activity reached unprecedented heights. ModernNext was a decisively forward-looking attitude. In the same way tradition formed the basis of innovation for the First Style, chaos and randomness were to instigate a new vitality for architecture and the city. Exhibition credits Curators: Seng Kuan, Angela Y. Pang, and Shiozaki Taishin Curatorial Assistants: Albert Lui, Siu Man, Po Po, and Jacob Wong Exhibition Installation: Ray Coffey, Jef Czekaj, Anita Kan, Sarah Lubin, Jesus Matheus, and Joanna Vouriotis Structural Consultants Dennis Chan and Hiraiwa Yoshiyuki General Contractor Woodcat LLC Construction Supervisor Ben Dryer Carpenters Alex Benevides and Ernesto Castellanos Dan Borelli, Director of Exhibitions David Zimmerman-Stuart, Exhibitions Coordinator Watch a behind-the-scenes look at the making of Shinohara Kazuo: ModernNext:Platform 11: Setting the Table

The Platform exhibition represents a year in the life of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Produced annually, the exhibition highlights a selection of work from the disciplines of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning and design, and design engineering. It exposes a rich and varied pedagogical culture committed to shaping the future of design. Documenting projects, research, events, publications, and more, Platform offers a curated view into the emerging topics, techniques, and dispositions within and beyond the GSD. In Setting the Table, the first student-led installment of the series, curators Esther Mira Bang, Lane Raffaldini Rubin, and Enrique Aureng Silva assembled a diverse body of work and cut it up—reinterpreting, rearranging, and ultimately composing a poetry revealed in each retelling. “This year marks a new approach to the way Platform is considered and produced,” says Dean Mohsen Mostafavi. “In the past, a faculty member collaborated with a team of students to devise an overall theme as a means of framing the work of the GSD from across its various disciplines and practices. While both the former and the current models of production are based on collaboration across various fields and among individuals with different backgrounds, on this occasion the whole concept has special resonance as it is constructed through a student rather than a faculty perspective. One distinguishing feature of this installment is its concern with what is placed on the table for consideration, both literally and metaphorically.”

“This year marks a new approach to the way Platform is considered and produced,” says Dean Mohsen Mostafavi. “In the past, a faculty member collaborated with a team of students to devise an overall theme as a means of framing the work of the GSD from across its various disciplines and practices. While both the former and the current models of production are based on collaboration across various fields and among individuals with different backgrounds, on this occasion the whole concept has special resonance as it is constructed through a student rather than a faculty perspective. One distinguishing feature of this installment is its concern with what is placed on the table for consideration, both literally and metaphorically.”

The curators adopted the use of a series of “tables” as configurational devices for bringing together a diverse body of work. These themes, with headings such as “Conveyor Belt,” “First Dates,” or “Tabula Plena,” enabled the curators to draw out a multiplicity of re-readings of the work. Each topic is conceived within as a specific collection or setting. The method deployed here is rational-objective, yet the result is a poetic construct. This strategy parallels the work and even more broadly the mission of the GSD, which lies at the intersection of imagination and implementation, of creativity and know-how. The capacity to conceive and realize complex design ideas and projects that can help enhance the built environment equally requires a range of negotiations and strategies between poiesis and praxis—a set of actions that exemplify the true art of making.

“To conceive of Platform as a means of framing people and objects, and to devise different relationships between them, is to approach the idea of a platform not as a neutral plane but as an active volume bringing together a multiplicity of conversations around it—literally and metaphorically as a table,” write Platform’s curators Esther Mira Bang, Lane Raffaldini Rubin, and Enrique Aureng Silva. “The table hosts a diverse body of topics from the witty banter of a first date to the weighty gravitas of a negotiation. Its materiality and temperament range from the cold sterility of a dissection to the adrenaline-pumping anxiety of an interrogation. Some guests are offered a seat at the table, some burst onto the scene uninvited, while still others must fight for their place.”

The curators adopted the use of a series of “tables” as configurational devices for bringing together a diverse body of work. These themes, with headings such as “Conveyor Belt,” “First Dates,” or “Tabula Plena,” enabled the curators to draw out a multiplicity of re-readings of the work. Each topic is conceived within as a specific collection or setting. The method deployed here is rational-objective, yet the result is a poetic construct. This strategy parallels the work and even more broadly the mission of the GSD, which lies at the intersection of imagination and implementation, of creativity and know-how. The capacity to conceive and realize complex design ideas and projects that can help enhance the built environment equally requires a range of negotiations and strategies between poiesis and praxis—a set of actions that exemplify the true art of making.

“To conceive of Platform as a means of framing people and objects, and to devise different relationships between them, is to approach the idea of a platform not as a neutral plane but as an active volume bringing together a multiplicity of conversations around it—literally and metaphorically as a table,” write Platform’s curators Esther Mira Bang, Lane Raffaldini Rubin, and Enrique Aureng Silva. “The table hosts a diverse body of topics from the witty banter of a first date to the weighty gravitas of a negotiation. Its materiality and temperament range from the cold sterility of a dissection to the adrenaline-pumping anxiety of an interrogation. Some guests are offered a seat at the table, some burst onto the scene uninvited, while still others must fight for their place.”

In the curatorial vision of Esther Mira Bang, Lane Raffaldini Rubin, and Enrique Aureng Silva, the table is reimagined as a new setting, “an active volume within the GSD, entangled within the very structure of the building, recasting projects upon a single shared datum,” they write. “After reading through hundreds of syllabi, event transcripts, project descriptions, research abstracts, and theses, we cut up these materials and collaged words and phrases that have special resonance for each table—shuffling them, reconfiguring them, juxtaposing them—ending up with a poetic construct: a table of contents that draws out the true art of setting the table.”

Curators

Esther Mira Bang

Lane Raffaldini Rubin

Enrique Aureng Silva

Design Team

Dan F. Borelli

Director of Exhibitions

David W. Zimmerman-Stuart

Exhibitions Coordinator

Installation Team

Liz Asch, Raymond Coffey,

Jef Czekaj, Anita Kan, Christine

April, Sarah Lubin, Jesus Matheus,

and Joanna Vouriotis

Acknowledgements

Mohsen Mostafavi

Dean and Alexander and Victoria

Wiley Professor of Design

Ken Stewart

Assistant Dean and Director of

Communications and Public

Programs

Ann Whiteside

Director of Frances Loeb

Library, Assistant Dean for

Information Services

Adam DeTour

Photographer

Martin Bechthold

Kumagai Professor of Architectural

Technology

Rachel Stefania Vroman

Manager, Digital Fabrication

Laboratory

In the curatorial vision of Esther Mira Bang, Lane Raffaldini Rubin, and Enrique Aureng Silva, the table is reimagined as a new setting, “an active volume within the GSD, entangled within the very structure of the building, recasting projects upon a single shared datum,” they write. “After reading through hundreds of syllabi, event transcripts, project descriptions, research abstracts, and theses, we cut up these materials and collaged words and phrases that have special resonance for each table—shuffling them, reconfiguring them, juxtaposing them—ending up with a poetic construct: a table of contents that draws out the true art of setting the table.”

Curators

Esther Mira Bang

Lane Raffaldini Rubin

Enrique Aureng Silva

Design Team

Dan F. Borelli

Director of Exhibitions

David W. Zimmerman-Stuart

Exhibitions Coordinator

Installation Team

Liz Asch, Raymond Coffey,

Jef Czekaj, Anita Kan, Christine

April, Sarah Lubin, Jesus Matheus,

and Joanna Vouriotis

Acknowledgements

Mohsen Mostafavi

Dean and Alexander and Victoria

Wiley Professor of Design

Ken Stewart

Assistant Dean and Director of

Communications and Public

Programs

Ann Whiteside

Director of Frances Loeb

Library, Assistant Dean for

Information Services

Adam DeTour

Photographer

Martin Bechthold

Kumagai Professor of Architectural

Technology

Rachel Stefania Vroman

Manager, Digital Fabrication

Laboratory

Mountains and the Rise of Landscape

To ask when we started looking at mountains is by no means the same as asking when we started to see them. Rather, it is to question what sorts of aesthetic and moral responses, what kinds of creative and reflective impulses, our new found regard for them prompted. It is evident enough that in a more or less recent geological time frame mountains have always just been there. It is possible that mountains, like the sea, best provide pleasure, visual and otherwise, when experienced from a (safe) physical and psychical distance. But it might also be the case that the pleasures mountains hold in store are of a learned and acquired sort.

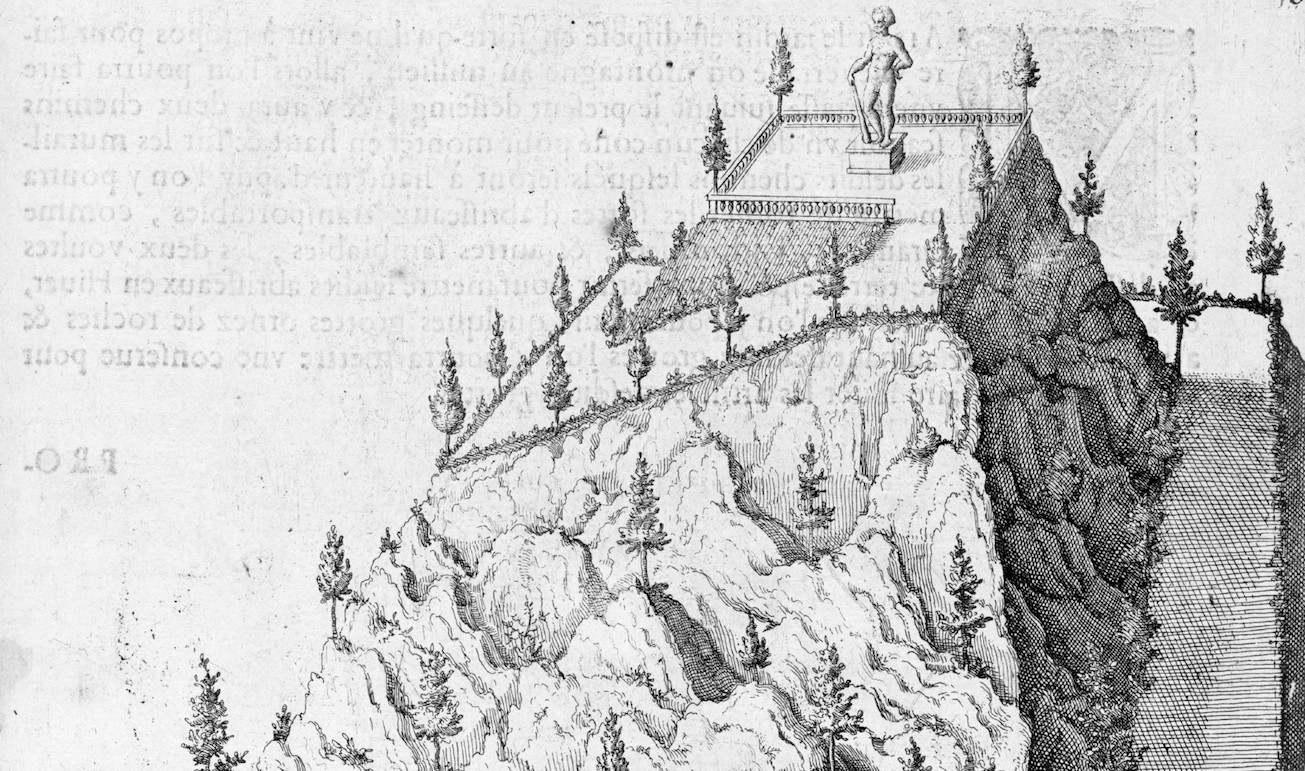

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1526-1569), The Tower of Babel, 1563. The mountain-like tower reaching toward Heaven can be seen as both an image of the human desire to create something monumental and a symbol of an impossible enterprise.

Which is also to say that mountains themselves, for all their unforgiving thereness, are themselves the products of unwitnessed Neptunian and Vulcanian tumults or divine judgment. For the late seventeenth-century theologian and cosmogonist Thomas Burnet, mountains were “nothing but great ruins.” A dawning appreciation of these wastelands appeared in the critical writings of John Dennis. Satirized as “Sir Tremendous Longinus” for his rehabilitation of the antique aesthetic category of the sublime, Dennis expressed the complex concept of “delightful horror.” Mountain gloom was ready to become mixed with mountain glory. More work was still to be done on the literary and philosophical front before the Romantic breakthrough, one high vantage point being the essayist Joseph Addison’s dream of finding himself in the Alps, “astonished at the discovery of such a Paradise amidst the wildness of those cold hoary landscapes.”

But a kindred innovation in seeing and feeling was called for in the formation of mountains and the rise of landscape. Mountains, among other earth forms, are both the medium and outcome of still-evolving habits of experiencing, making, and imagining. Architects and landscape architects, mutually occupied with the horizontal surface, have had a touch equally as searching as that of mountaineers and poets in sensing the terrain. Mountains and the Rise of Landscape is the culmination of a curatorial project and a research seminar conducted at the Graduate School of Design, the latter focusing on the question, How do you model a mountain? The installation in the Druker Design Gallery and continuing in the Frances Loeb Library collects diverse objects and scientific instruments, drawings, photographs, and motion pictures of built and imagined projects and presents invitingly challenging modes of seeing (and hearing!) mountains of varied definition. Allied with the work of artists, visionaries, and interpreters of natural and cultural meaning, they propose new and foregone possibilities of perception and form-making in the acts of leveling and grading, cutting and filling, shaping and contouring, mapping and modeling, of reimagining “matter out of place,” and finally of stacking the odds and mounting the possibilities.

Mountains and the Rise of Landscape offers five thematic sections:

Mountain Lines of Beauty

Mild mountaineers, John Ruskin (1819–1900) and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) were among the first theorists, designers, and architects to teach us that the “line” formed by crests, peaks, and ridges presents an exemplary form of beauty. The invention of the panorama and the photomechanical reproduction of mountain views transformed a geophysical phenomenon into an object of aesthetic value and topographical knowledge. Guidebooks, geographical manuals, and maps glorified specific ranges by showing their most beautiful contours. To define a single mountain or group of mountains as a “line,” however, implies a process of abstraction. This process is both enhanced and complicated by contemporary tools such as CAD, GIS, and GPS. To draw the most important mountain ranges of our contemporary world as “mountain lines of beauty”—the phrase is evidently inspired by the eighteenth century painter William Hogarth’s analysis of the serpentine, S-shaped “line of beauty”—should not be seen as a simplified way to represent them. Rather, the difficulty of representation itself becomes visible in the constructedness of the lines. Through them the possibility arises, again, of our being surprised by the sublimity, as well as the beauty, of the mountains.

![The Great Tumulus or Tomb of Midas, Gordion [Gordium], ancient capital of Phrygia, Yassihüyük, Turkey, 740BC, public domain Tumuli, also known as barrows or kurgans, are hills of earth or stone containing the remains of the dead. They are found all over Europe, in various regions of East Asia, as well as in the Indian cultures of east-central North America](https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Web-Manmade-7-HIGH-300x200.jpg)

The Great Tumulus or Tomb of Midas.

Tumuli, also known as barrows or kurgans, are hills of earth or stone containing the remains of the dead. They are found all over Europe, in various regions of East Asia, as well as in the Indian cultures of east-central North America

Camouflage: Among the first who climbed high mountains in antiquity were members of the military, in search of an advantageously elevated view of their enemy’s position. From the seventeenth century onward, many mountainous regions were massively fortified, with military infrastructures placed strategically to take advantage of their secluded impregnability. The photographer Leo Fabrizio has documented traces of former military constructions hidden in the most remote areas of Alpine Switzerland. His visual archeology of camouflage techniques employed by the Swiss military exposes the unfamiliar territory of a landscape that still appears “natural” while being completely transformed from within.

Glaciers are in retreat throughout the world. Celebrated and studied during the eighteenth century as sublime objects—sung of by poets and depicted by landscape painters—glaciers register today as metonymies of global climate change and vanishing natural and scenic phenomena. Geneva-based composers Olga Kokcharova and Gianluca Ruggeri have explored the fascinating soundscape of the Mont Miné Glacier in the Swiss canton of Valais. Since 2000, the 4.9 mile-long glacier has lost about eighty-five feet per year. To hear the “voice” of a glacier compellingly questions the visual bias of the landscape-oriented perspective. The mysterious sounds of the white masses bear melancholy aural testimony to the progressive disappearance of a titanic natural feature.

Inhabitants of the Alpine regions have practiced transhumance for centuries, droving livestock between the valleys in winter and the high mountain pastures in summer. Many of the wooden or stone structures built by farmers to shelter their cattle and themselves have been abandoned, ruined, and in some instances transformed into chalets. Martino Pedrozzi, a Ticino-based architect, has worked for a decade in the remote valleys of southern Switzerland. His Recompositions, carried out with his students at the Mendrisio Academy of Architecture and other volunteers, consist in repairing the existing structures or in composing a new object from the abandoned material. The resulting architectural objects are designedly functionless; they are poetic metaphors and visual documents of a past that is at risk of disappearance.

Credits:

GSD Administration

Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design

Patricia Roberts, Executive Dean

Ken Stewart, Assistant Dean and Director of Communications and Public Programs

Paige Johnston, Manager of Public Programs

Travis Dagenais, Assistant Director of Communications

Exhibition Curation and Design

Michael Jakob, Curator

Anita Berrizbeitia, Co-curator

Pablo Pérez-Ramos, Co-curator

Edward Eigen, Co-curator

Dan Borelli, Director of Exhibitions

David Zimmerman-Stuart, Exhibitions Coordinator

Paola Sturla, Content Curator

Gustavo Romanillos Arroyo, Research

Peeraphol Sangthongjai, Research

Model Fabrication

Carson Booth, MLA ‘19

Jacqueline Wong, MArch I ‘22

Installation Team

Christine April, Liz Asch, Ray Coffey, Jef Czekaj, Jesus Matheus, Anita Kan, Sarah Lubin, Sarah Uziel, Joanna Vourioits, Isabel Brostella, MLA I AP ‘19, Isabella Frontado, MLA I & MDES ADPD ‘20, Melissa Naranjo, MLA I AP ‘19

Photograph Credits

Jean-Michel Landecy, Iwan Baan, Pino Brioschi, Alex MacLean, Hilaire Dumoulin

Art Credits

Leo Fabrizio, Olga Kokcharova, Gianluca Ruggeri, Martino Pedrozzi, Steve Tobin, Andrés Moya

SPECIAL THANKS to

Frances Loeb Library, Chiara Geroldi, Isabel Formica Jakob, and Swissnex Boston

Mountains and the Rise of Landscape is made possible by the Dan Urban Kiley Fund