The GSD Speaks Your Language

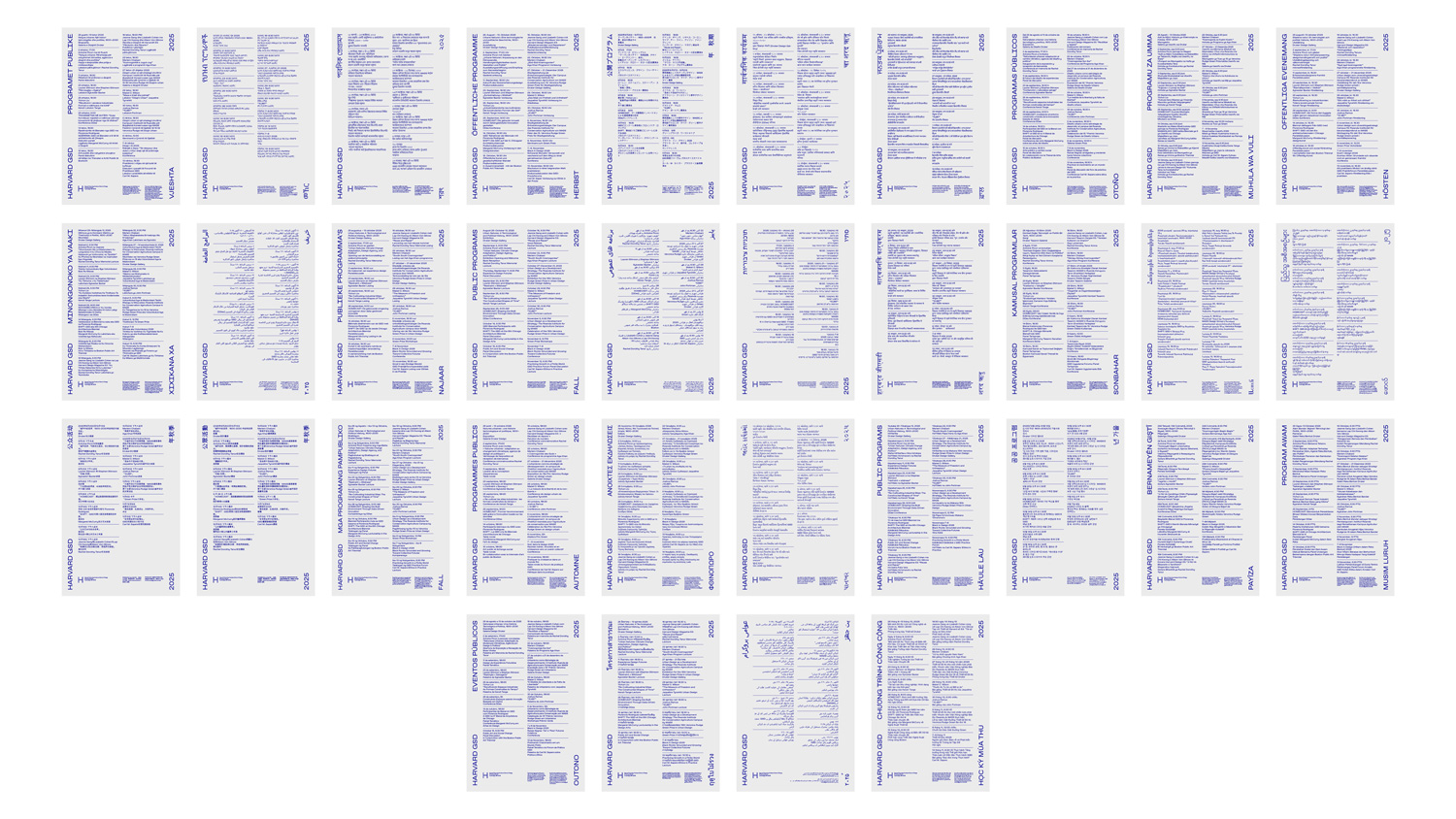

Students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design come from more than 60 countries and speak at least 56 languages, with 34 of them being students’ first or preferred languages, according to a survey of current and incoming students in July 2025. The visual identity of our fall 2025 public programs is translated into those 34 languages, celebrating the internationality of the GSD community.

The project was possible only with the assistance of student and alumni volunteers who translated and reviewed the posters. Among them is Adria Meira (MDes ’26), a Brazilian student who translated the Portuguese version of the poster. “Ensuring that the poster appeared in Portuguese was important to me as a representation of my culture, language, and country,” says Meira.

Valentine Geze (MDE ’26), worked on the French version. “I wanted to support this project because I see translation as a way to both welcome and celebrate the diversity of the GSD,” says Geze. “Supporting immigrants and honoring the languages spoken here feels especially important now; making space for many voices expands the perspectives that shape our academic and personal experiences.”

In past years, the GSD has collaborated with designers to create unique visual identities and promotional materials for the public programs. This year, the GSD’s own art director Chad Kloepfer, and Willis Kingery, graphic design consultant, designed the posters to represent the linguistic diversity of the GSD.

This multilingual project highlights the GSD’s commitment to welcoming students from around the world. “The GSD is one of the most international schools at Harvard,” said Dean Sarah Whiting in spring 2025. “Our international makeup goes back to the founding of the GSD. It is part of our DNA—our student body, our faculty, our staff, and the discipline and practice of design all thrive on this internationalism. The extraordinary breadth of experience and perspectives that the international members of our community provide is essential to who we are.”

Meira is part of the international community that Dean Whiting described. For her, participation in the poster project is “a way to highlight the contributions of the Brazilian community, which has 12 members at the school.” The student organization Brazil GSD, of which Meira is a part, “enriches the life of the school for everyone and provides much needed support to those of us studying far from home at such a challenging time.”

| Language | Translators |

|---|---|

| Amharic | Anonymous |

| Arabic | Sara Abduljawad (MLA ’27) |

| Armenian | Shant Armenian (MArch ’28) |

| Bangla | Anonymous |

| Burmese | Htet H Hlaing (MArch ’26) |

| Chinese (Simplified & Traditional) | Anson Leung (MLA ’26) |

| Dutch | Emma van Zuthem (MDes ’27) |

| Farsi | Soroush Yeganeh (MArch ’26) |

| Filipino | Maita S. Hagad (MLA ’28) |

| French | Valentine Geze (MDE ’26) |

| German | Robin Albrecht (MArch ’26) |

| Greek | Styliani Rossikopoulou Pappa (MDes ’19) & Alkiviadis Pyliotis (MArch ’20) |

| Gujarati | Aum Gohil (MAUD ’27) |

| Hebrew | Anonymous |

| Hindi | Malvika Dwivedi (MDes ’27) |

| Japanese | Anonymous |

| Korean | Jeongjoon Lee (MArch ’27) |

| Kurdish | Leyla Uysal (MDes ’24, MLA ’27) |

| Malay | Joshua Teo (MDes ’26) |

| Marathi | Riddhi Kasar (MDE ’26) |

| Portuguese | Adria Meira (MDes ’26) |

| Punjabi | Anonymous |

| Spanish | Dana Barale Burdman (MDes ’26) |

| Swahili | Martha Oloo (MLA ’27) |

| Swedish | Hannah Ahlblad (PhD ’30) |

| Thai | Sirinda (Kaew) Limsong (MDE ’26) |

| Tsonga | Xiluva Mbungela (MDes ’26) |

| Turkish | Defne Ergun (MArch ’28) |

| Urdu | Omer Yousuf MUP ’26 |

| Vietnamese | Tuân Cao (MAUD ’27) |

Translation of Albanian and ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian) was provided by We Are Very.

What’s in a Grid?

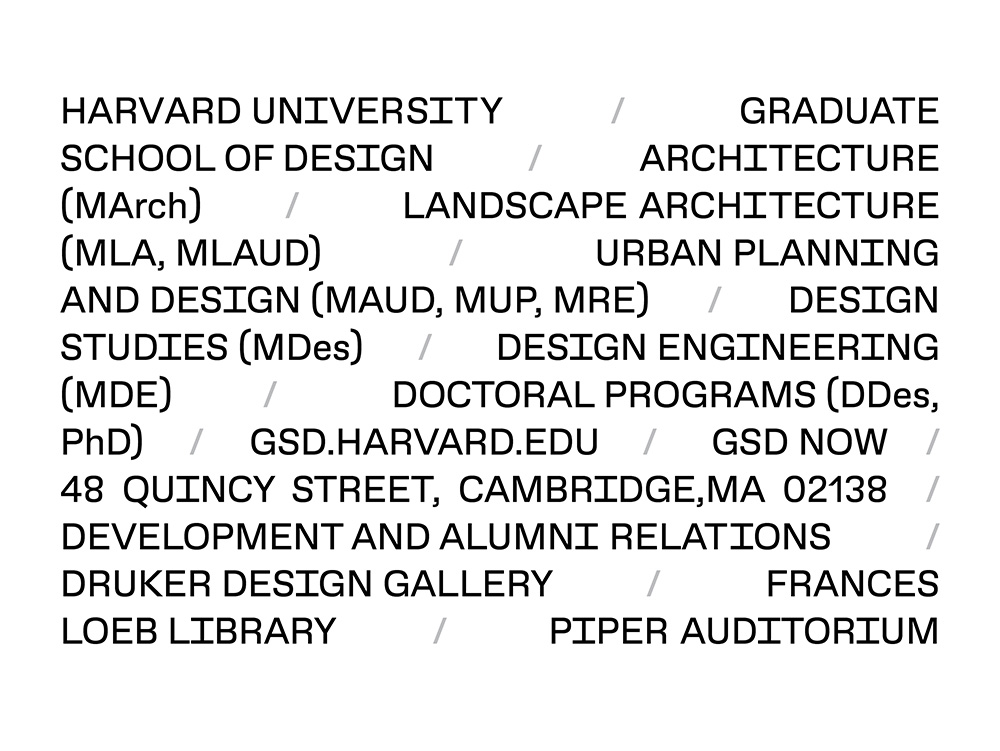

Each year, the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) creates a visual identity for commencement exercises and related events and exhibitions. This year’s design, developed by art director Chad Kloepfer and graphic design consultant Willis Kingery, uses color to define grids of varying widths that frame text in GSD Gothic, the School’s custom typeface. The pattern appears on tickets for commencement events, exhibition title walls, banners throughout the school, and website graphics.

For the past several years, the commencement identity has utilized formal graphic treatments: repeating forms, eccentric shapes, and geometric patterns. In 2024, for example, the design featured off-cast forms found in the trays. Moving in a different direction for the Class of 2025, Kloepfer chose to emphasize color.

Seeking to “deploy color in a meaningful way,” Kloepfer and Kingery devised each grid pattern with a “core color” linked to the GSD’s identity system. The School’s signature green, pink, blue, and yellow anchor the rest of the color choices in a given iteration, with the designers working toward a harmonious palette. The visual identity leads to surprisingly complex results, especially in areas where bars of color overlap, creating a woven effect. Some of the title treatments for end-of-year exhibitions in the Druker Design Gallery, for example, feature a combination of translucent tape and paint to achieve the right intensity of color where the vertical and horizontal elements of the grid meet.The grid structure was inspired in part by tartans, distinctive woven patterns created by intersecting strips of varying width. The specific variations of color and weave in tartans have historically carried symbolic meanings. In architecture, the “tartan grid” refers to a grid system where the vertical and horizontal elements are not necessarily aligned or spaced evenly. The irregular features of these patterns create a sense of dynamism, whether in space or textiles.

Another inspiration comes from Karel Martens, the Amsterdam-based designer who developed the visual identity for the GSD’s public programs for the 2024–2025 school year. Marten’s monoprints in particular, on which two colors overlap to create a third, served as a point of reference for Kloepfer and Kingery. “The monoprints are all about time,” says Kloepfer. “The ink dries and then you can print again a day or two later. It’s a beautiful way to work in our era of high-speed.”

Paperwork: An Interview with Karel Martens and the Martens and Martens Studio

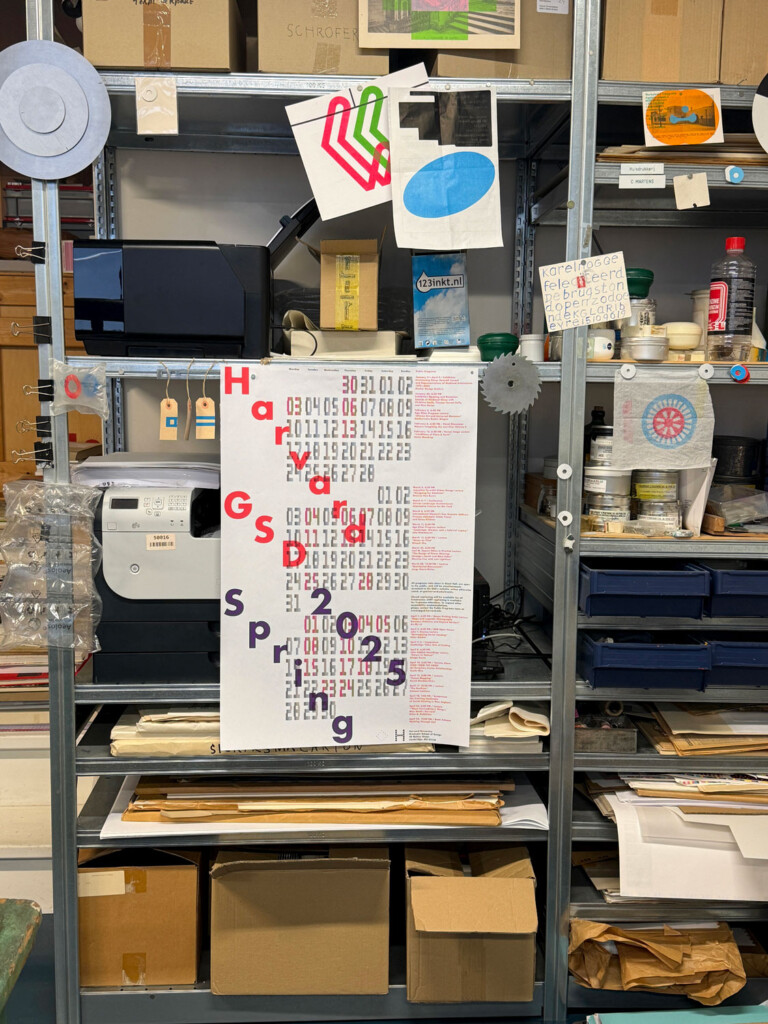

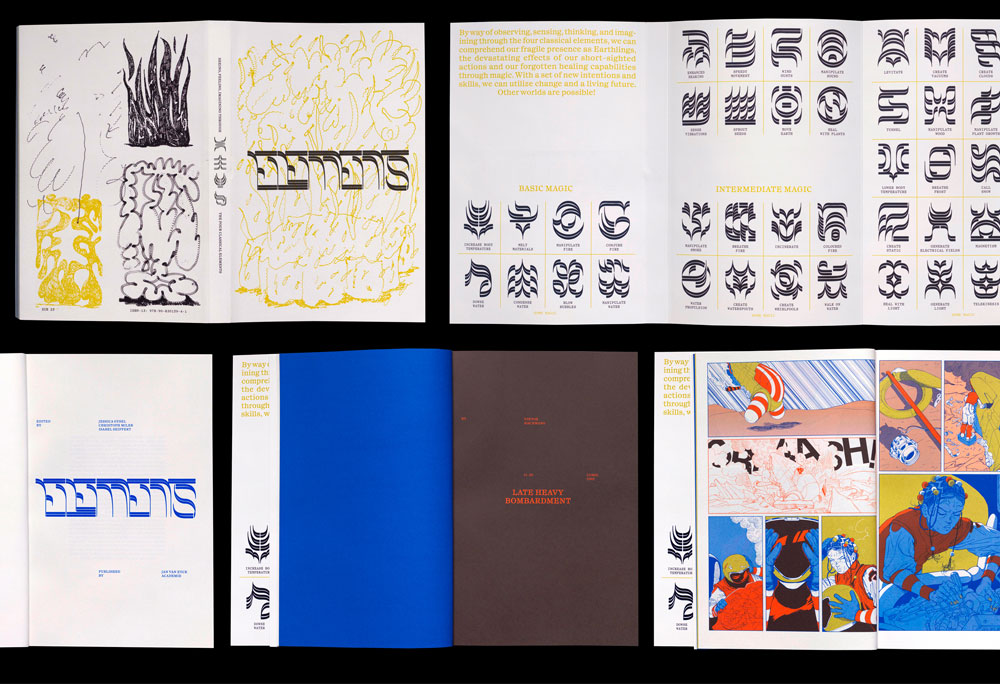

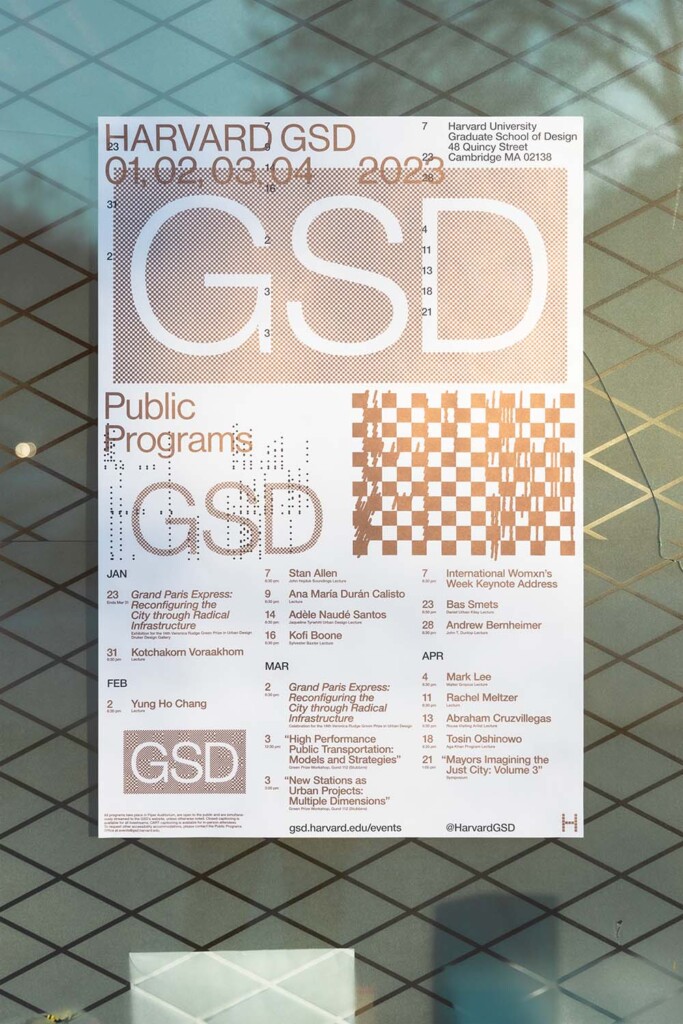

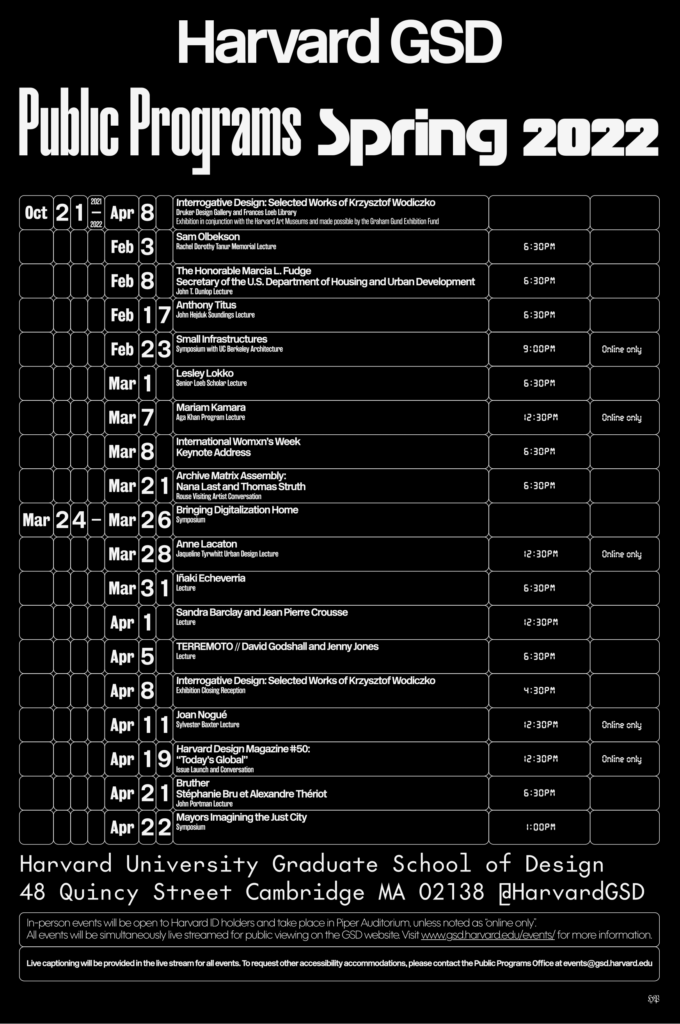

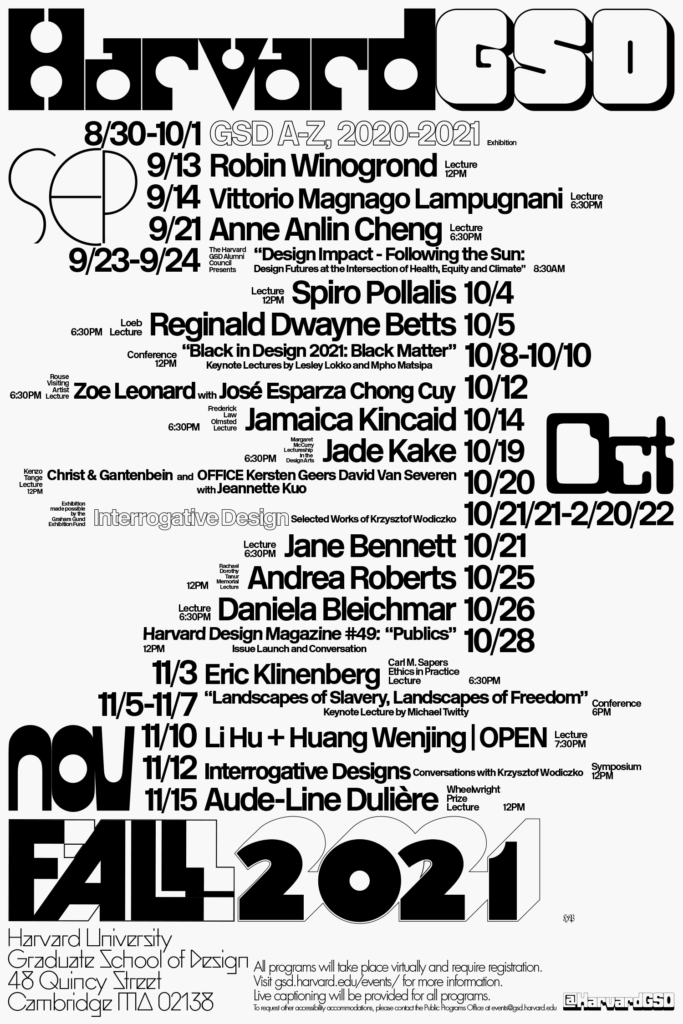

A pair of colorful calendars appeared around Gund Hall during the 2024–2025 academic year to announce the full schedule of public programs at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). Designed by Martens and Martens studio in the Netherlands, the posters reflect the typographical experiments undertaken over the past six decades by Karel Martens, the studio’s founder.

Martens created the visual identity for the GSD’s public programs as he prepares for a retrospective at the Stedeljik Museum Amsterdam , drawing from a design career spanning from the days of punchcutters to the Creative Cloud. Throughout, Martens has maintained a meticulous focus on the interactions of color, typography, and printing techniques, balanced by an infectiously playful attitude toward the conventions of design.

Known today primarily as a graphic designer, with much of his influential work collected in the now-classic volume Drukwerk, Martens began his career when design was an inherently interdisciplinary pursuit. Architecture in particular has served as a source of inspiration as well as the subject of legendary projects he produced and oversaw, including the journal OASE. Trained as a fine artist, Martens also creates textiles, design objects, and kinetic sculptures, a selection of which will be part of the Stedeljik exhibition.

For decades, pedagogy has been integral to Martens’s design work, which is often produced collaboratively and through trial-and-error. This ethos is at the heart of the school he founded, Werkplaats Typografie, and also extends to the dynamic of the studio itself. Today, Martens and Martens includes Diederik Martens, Klaartje Martens, and Susu Lee, all of whom contributed to the visual identity for the GSD’s public programs.

For nearly twenty years, the GSD has commissioned outside designers to create posters and other materials to announce public programs. Chad Kloepfer, art director at the GSD, and Willis Kingery, graphic design consultant for the school, spoke with the Martens and Martens team about their collaboration with the GSD and how the work environment in the studio often flips the roles of instructor and student in a playful yet intensive search for new forms and modes of expression.

Willis Kingery: We wanted to start with an impossible and kind of silly question. How many posters have you designed, Karel?

Karel Martens: [laughs] Too many! More than a hundred. My first was for a movie theater.

WK: Do you still find challenges to be met in designing posters? Has anything in your approach to making a poster changed from your early career to now? Are you surprised by the endurance of the format?

KM: There’s been a departure from some past media. You used to make sketches with your pencil, then it went out to an official printer, and you had to make films and do all that kind of thing. So now it’s much more direct, and much easier in a way. That doesn’t always mean that the results are better, but it’s completely different from when I started my career in the time of letterpress. In that time, you had to work with material, to work with a printer and what they had in their collection. I used to deal with small printers and whatever typefaces they had in their drawers.

WK: And have there been any changes in the thought process that goes into the designing of a poster?

KM: I always try to imagine what kind of public I’m addressing, and who and what kind of public the poster should be for. A public for me is one of the players in the game. You have a designer and a printer, but also the public, and of course the commissioner. There has to be a kind of harmony between these. Working with the GSD, I had a feeling we understood each other very well. The challenge in this case, of course, is the distance. You don’t smell the ink.

WK: One of your earliest teaching assignments to your students in Arnhem in the late 1970s was to design a typographic layout for one month of a calendar page, which was then printed by letterpress in Futura. Curiously, upon receiving the commission from the GSD in 2024 and 2025, you gave yourself your own assignment, creating a calendar system using Futura as the primary typeface. Can you tell us what motivated this?

KM: I’ve always been fascinated by numbers and time. Time for me is a mysterious thing. A calendar is a magical thing, and a daily calendar really makes you see that time is going. [The two GSD posters represent] two parts from a whole year. You see the panorama of the whole year, all the numbers, all the days, and from those there are a few you pick out. Exciting days. I can imagine that for students you can be confronted with the highlights of the year.

WK: The release of your two posters line up elegantly with an auspicious anniversary: Paul Renner began working on the typeface that would become Futura in the summer of 1924, and this was later picked up for commercial development by the Bauer type foundry in the winter of 1925 and eventually released in 1927 as Futura. So, on its unofficial 100th anniversary, can you tell us about your selection of Futura for the GSD posters? Futura feels like a typeface you’ve fallen in and out of love and trust with over the course of your career, but it seems to have enduring relevance for you in architectural contexts.

KM: Futura still contains a kind of thesis about the future in my opinion. As a designer you can go crazy looking at all the typefaces. I see typefaces as a kind of representation of the human voice. And a human voice can be reflected on a poster depending on what someone would like to tell. A poster for a professor of mathematics might use another typeface, and it would be different again if it were for a book or magazine.

Diederik Martens: You’re aiming for a tone of voice?

KM: It’s also connected to the creation of hierarchy, which acts as a guide. A caption should be different than a footnote, through size or position. In that way I always learned a lot from the catalogues that Wim Crouwel made for the Stedelijk Museum. There’s only one typeface, one size, one leading. Only the position on the page is important. In this way you create your own rules. I remember reading Jan Tschichold for the first time—his book on book design. After two pages, I closed it. I thought I can never act that clever. I later saw there was a distinction between his falsch und richtig (“good” and “not good”). Sometimes “not good” is better than “good.” When you make rules for something it is already dead.

Chad Kloepfer: Given that the poster you’ve designed for the GSD neatly outlines the days of a semester at a design school, could you each tell us what a day on the Silodam at Martens Martens looks like?

KM: I’m a workaholic.

DM: [laughs] You, no! So, you wake up in the morning and you go to the gym.

KM: Yes, I do some exercises, have some breakfast, and then I go to the studio around half past nine, which is in the same building, so I don’t have to walk far.

Susu Lee: Me and Diederik come to the studio at 10. I come three days a week. We always check what we’re going to do for the day. I make a schedule in my head, otherwise I get lost because there are a lot of things to do here. Then me and Karel work together behind one computer. It’s always nice to be here. And Diederik is working on typefaces, making fonts, animations.

DM: If they start working here in the studio I can always go next door to Karel’s house, because it’s quiet, and I can make phone calls, handle the administration and Karel’s calendar, make a typeface or animation. Then we have lunch together around 1 o’clock, baking eggs or something like that. Susu likes to bring a Korean lunch.

SL: Working here with Karel—I don’t know if this is the right word for it—but it always feels like a playground. There’s so much to see, and Karel’s ideas are crazy. He keeps thinking of new stuff and is always willing to try out something new every time. From trying everything out, we of course make some mistakes, but then it somehow becomes the work.

DM: It’s always a lot of trial and error. It might sound repetitive, but it somehow never repeats. Sometimes you might think one work is a copy of another, but we’re always looking backwards in order to go forward. We don’t believe there’s one best way. We’re always taking one step forward, two steps backward, and so on. Every design process here is like that, reinventing almost the same thing.

WK: Do you ever take a break from designing every day?

KM: For me it’s an ongoing process: the client has a question and I have to find an answer. I have to find the ingredients that I can use for it, and I’m always analyzing that. Then you get an idea, and try it. If it’s good you keep it. If it isn’t, you put it in the trash can and you start again.

DM: It’s like you’re a detective. A detective has to be a workaholic, they can’t hide behind their desk and wait to start working. They’re always gathering information.

WK: Do you remember the moment that you developed a sense of vocation as a designer?

KM: It was from the moment when I began studying at art school. That was the nicest part. You develop things yourself, in collaboration with other people or not. I was around 20, and at that time art school was five years, and in my case the curriculum of the school was really broad. It was more of a general art education. The term “graphic design” didn’t exist yet for us at that time. So you took classes from all the teachers, developing ideas in whatever medium you wanted. In my opinion design education today is too focused on design, design, design. It should result from a way of thinking. I don’t see a difference in the kind of thinking that is needed to make a dress or a poster or a stamp or whatever. You’re facing a problem. Graphic design may be the ingredients for the technical realization of the problem, in combination with materials, but I try to see everything as new—as a possibility for new work. It’s surprising how so much is all the same. But now we are preparing for the Stedelijk exhibition, and I discovered that I too did a lot of things too many times.

CK: We know that not just the practice of design, but also the teaching of design is very important to you. In 1998 you founded the post-graduate school Werkplaats Typografie in Arnhem, Netherlands, with the purpose of learning through working on practical design assignments and commissions. Do you still think this is the best model for a design education?

KM: What was nice about the Werkplaats was that from the beginning my studio was in the school as a permanent location. We were always thinking when we created the Werkplaats Typografie that we should do real things. When you can create ideal situations for yourself, then it’s not so difficult, and also not so exciting in my opinion. In this way I was able to work less and also do a lot. For example, I always made the architectural journal OASE with a student. In fact, the student did it and I was guarding them. The students were always motivated to make the best possible work, in contact with the architects, who were also designers. The students would hear the architects’ comments, make their own strategies, and go to the printer with their own ideas.

CK: What do you think Susu? What’s your sense from working in the studio?

KM: Don’t tell all the secrets!

SL: I studied at the [Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam], and I would say it has a similar educational program to the Werkplaats. We had a lot of applied assignments, such as designing a poster for the Rietveld or other institutions in Amsterdam. I don’t know if it’s the right answer, but whenever I’m in Karel’s studio I feel like Karel is teaching me. I was actually thinking a few weeks ago what it would have been like to be at the Werkplaats while Karel was at the Werkplaats. But now I’m at the studio and can just talk to Karel about commissioned work and assignments and how to develop them. I really appreciate it. I also appreciate how Karel directs. He doesn’t say, “this poster should be like this,” or “this poster should read in this way.” He always puts it in a really poetic way. For example, with the GSD poster Karel told me that the front and back layers of the typography have to fight each other. The front and back layers need to be in a fight. At first, I was like, what does that mean? Then I looked back at his work in Drukwerk and started to understand, oh, this is what Karel means.

CK: You had mentioned something about time as a component of your thinking and work, and looking back at your books we see everything from overlapping numbers and dingbats to graphic patterns and typeface design where there is a real kinetic quality to the work. We have even seen this translated into videos and sculptures. What is the relation of time and movement to your work, and is it a conscious component as you are engaged on a project?

KM. It’s all based on choreography I believe. I remember already as a child I was interested in how a watch worked. I remember my father had a type writing machine; I could not read in this time, and as he was typing I was wondering what is a typeface, and what are letters? And that with 26 characters from an alphabet you can make so many kinds of meanings? That for me is still a kind of mystery. Same with colors. With basically a few colors you can make all the colors of the world. You can take this for granted—and this is also okay—but for me it’s still a mystery that you can make from yellow and blue—green! Three! Two makes three.

DM: Has time something to do with it?

KM: Yes, even in printing. With the monoprints you are printing, and then you cannot touch them. And the next day you can touch them again. I never have a fixed plan, only a beginning. I start printing something, and then it is asking me for something more. And sometimes they go to the trashcan, and sometimes they receive more and more. I still have the feeling that I’m the student. That I’m the one who has to learn.

DM: And we feel like the ones who are the teachers!

SL: Sometimes I have the feeling that Karel is really like a child. In a good way! Always wondering, finding new things—in his crazy collections, his crazy shelves.

WK: Karel, you’ve mentioned that the 2mm grid structure for OASE was inspired by watching a documentary about the architect Dom Hans van der Laan. Similarly, you’ve cited the work of Auguste Perret as a point of inspiration for the vertical strips in your beach installation in Le Havre. Have you experienced any other moments of interdisciplinary connection after a lifetime of working with architects? And conversely, have any of your collaborators in architecture translated lessons learned from you and your work into their own projects?

KM: Life is a process. I was never even intending to study design. The word “design” didn’t exist at that time. I was intending to study mathematics, but everything then depended on the teachers. On the last day of the semester the teachers would give a kind of speech, and I had this teacher that was always explaining the failures of mathematics. He was playing with his ideas about what mathematics should be, and I thought this is the forefront of the future. But then, I’m dyslexic, so I could not finish my high school and therefore advance on to university. So, I had to do something else. My sister was in the art school and she always said, “you have to come to the art school.” From the moment of joining the art school I felt happy. There were all kinds of things that you could do.

DM: But you never recognized that an architect was inspired by you?

KM: No.

DM: Did you ever think about being an architect?

KM: Why? To save money? No. There are so many things to do. But I have a feeling that education is too focused on disciplines. As a young person you could learn just as much from a person who is teaching aviation or, I don’t know, anything! As a young person you need a full color of opportunity. Not only graphic design, not only architecture.

CK: That sounds similar to a Bauhaus form of education. Not a single discipline, but a bigger, circular idea. I had a question about the tools designers use. The tools we use have changed dramatically over the course of your career. I feel like when a new tool is invented, it’s easy to become a victim of it. How have you stayed above that?

DM: Yes, victim of tools.

KM: [smiling] That term “victim” is very strong. I had said my career started with letterpress. I remember I had to teach my students the way monotype was working approximately. It was a very big thing, so I split it up in parts, and I started telling them about how it works, how fantastic it was as a system for translating compositions onto this hole-punched paper. Then there was a lecture at the time at the school from the designer Gerard Unger, a Dutch type designer. And he starts his lecture, “Of course, all of you know how Monotype works…” Nobody. I was also in the audience and I was looking around thinking, what have I done wrong? For me that was a learning process in teaching. You have to deal with curiosity, and you have to make students curious. That tool was not much longer in use. Tools are always changing. After that we went to the IBM Composer, for example. In a way not a serious instrument, without special control over spacing, but you still had to deal with it because you’d have clients without large budgets. And then came cameras and phototypesetting, that came with its own rules which you then had to deal with.

DM: I think you never became a victim of tools because you’re always thinking, “What can I do in a certain kind of situation?” You can use a special tool or not, but you’re never thinking in tools. You’re thinking through your search for solutions. You find the tool for it through the searching.

KM: And I’m always thinking, can we do more with this tool than what it’s made for?

DM: It’s like when you first started using the computer. You didn’t know what to do with it. But then you started to do things with it that no one had done before, because everyone else was thinking, “computers are for this or that,” but you found things outside of the intended uses.

WK: To address another kind of circularity, many designers speak through a consistent vocabulary or approach. In a way you’ve been uniquely committed to a consistent set of visual interests and formal expressions throughout your career, and you continue to possess an almost monastic devotion to developing your craft and personal explorations. Do you ever make things—small experiments in the studio—that you discard because they don’t feel like they fit into your larger body of work?

DM: No!

KM: It’s happening very often at the moment because I have to dive into my own past: 60 years of work. Save everything. I’m seeing things I made 60 years ago and I’m now thinking—more than at the moment when I did it—”Wow, not so bad!”

CK: Since preparations for your retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum are so much about the past, if we’re looking forward, is there anything you wish you could still do? Is there anything that you haven’t had the opportunity to do yet?

KM: This is the beginning of my worries, especially at my age. It’s for sure that I don’t have so many more years in life. I’d like to use them for my work. But the strange thing is—apart from that my wife has sadly passed away—there’s a kind of strange world that you get in, where you’re then working on your own portrait. To be honest, I was so surprised that they were asking me for such a show, that it actually motivated me to go ahead, to show myself in the best way.

DM: But what do you still want to do in the future?

SL: This I know. Because I also asked it to Karel one time. Karel always wants to do something. I asked him what do you want to do besides graphic design? Besides making books and publications? And he said he wants to make BIG sculptures. So I said, we can do it after we’re done with the Stedelijk! But he said, no, it will be too much work.

DM: The exhibition consumes a lot of energy and time and concentration and space, but we still think when the preparations for the exhibition end, we’ll have time to do lots of other kinds of stuff. But it always goes on and on, and then something else comes up, and you think you can start something new, but you can’t plan for anything. It’s like we’re on a train that will never stop, and you have to live with it in a way. But we want to do a LOT. When? We’re always willing, but where is the time?

KM: You cannot do everything. I’m interested in 3D printing, but I may not get the chance to do it. I have a small studio now. The machines are too big. I have at most the space to make something at the scale of A3. That’s the maximum. But from the other side, limitation can point your energies into small things. I sometimes wish to make a big thing, in concrete for example. You can now 3D print in concrete. What’s happening in your school with this kind of thing?

DM: He wants to use your school’s concrete printer!

CK: We’ll talk to facilities about that!

KM: Well, this is the nice thing about education, that you see young people taking decisions. I always had the feeling that I was the student and they were the teachers. Students are always inventing things. It’s amazing to see that you’re in a positive environment, so you should work with young people and see how they are making things. That’s really a privilege, I believe.

CK: That’s a really beautiful and perfect way to close this out. Thank you so much.

WK: Karel, on behalf of many designers, I’m very glad that you didn’t study mathematics!

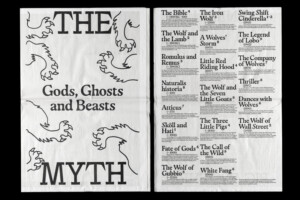

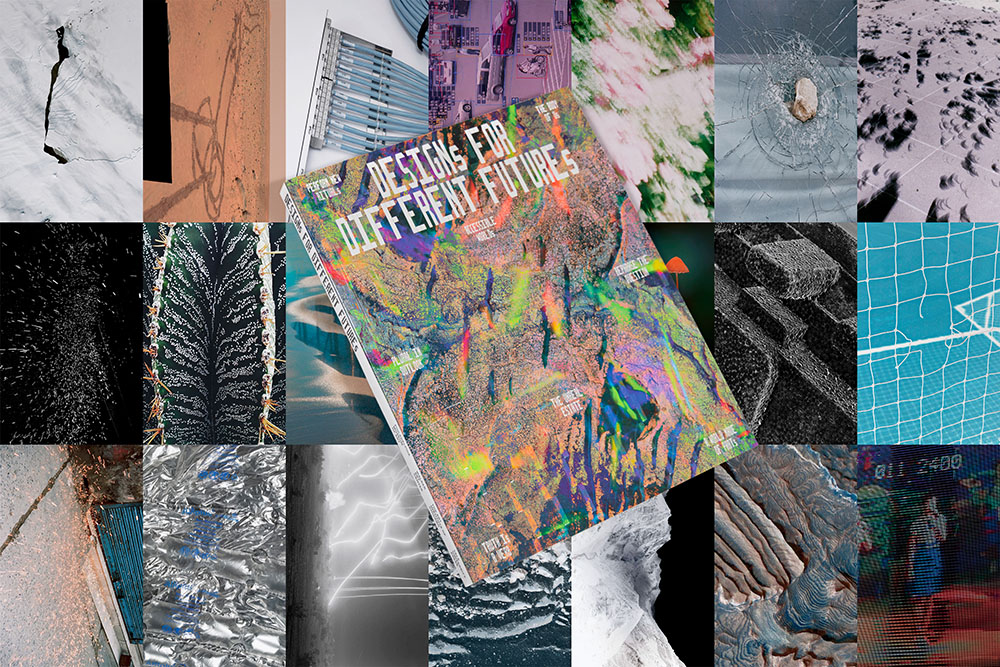

Design and Time: An Interview with Offshore

The public program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design features speakers in the design fields and beyond. The series of talks, conferences, and conversations offers an opportunity for the public to join members of the GSD community in cross-disciplinary discussions about the research driving design today.

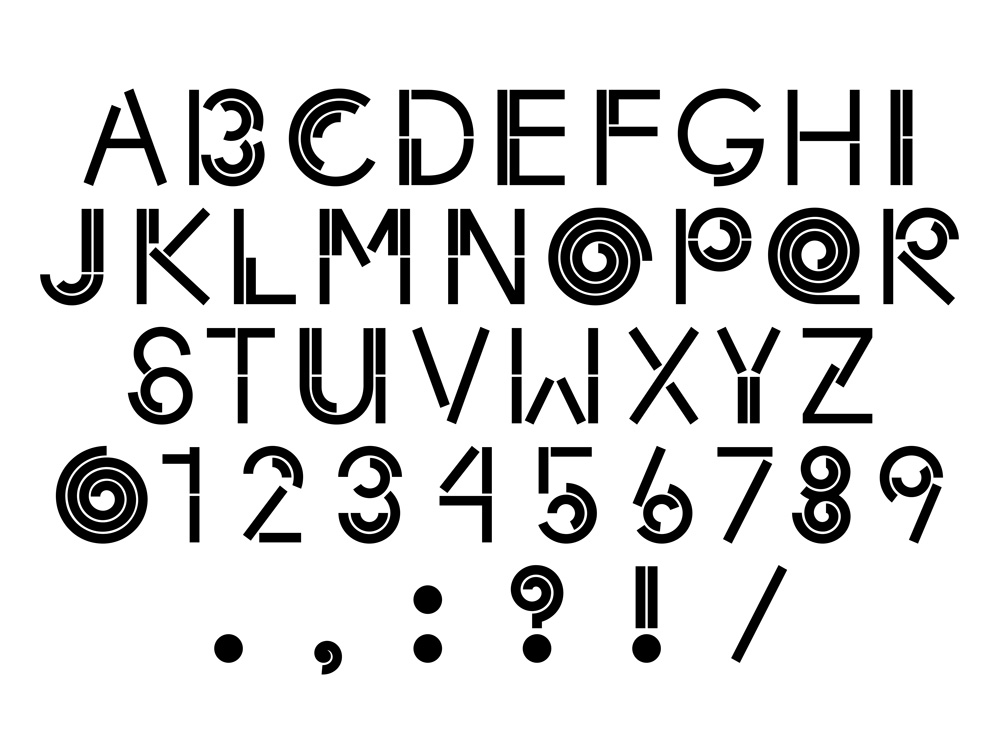

Each year, in an effort to extend an invitation to these programs as widely as possible, the GSD asks graphic designers to create a visual identity that conveys the program’s spirit and mission. For the 2023–2024 academic year, Offshore , the design practice of Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miler, took up that challenge. They created print and digital materials featuring a swirling motif and a spiral-like typeface that distill the energy and intellectual curiosity of the School’s events. To better understand how graphic design relates to the GSD’s public program, Art Director Chad Kloepfer exchanged questions with Miler and Seiffert over email.

Chad Kloepfer: Through innovative printing and custom typography, this year’s poster is a literal whirlwind of color and type. What did you hope to convey through this treatment?

Offshore: A whirlwind of color and type—that is such a nice description. The graphic language for architecture-related projects often features monochrome or more toned-down and serious visual gestures. Additionally, the pandemic years have felt very monotonous in many ways. We wanted to bring some energy and liveliness to this project. It was important for us to convey a vibrant, dynamic, and, to some extent, action-oriented mood.

There is a structured but organic feel to both the typeface and layout, the spiral being a predominant gesture. How did you arrive at this graphic device?

During the design process, we were very focused on striking a balance between sharp, clear, and bold graphical forms while allowing movement and avoiding rigidity. To us, this represents a commitment to precision that does not feel “square,” if that makes sense. The gesture of the spiral comes from the idea that this visual identity lives for one academic year, one cycle, so to say. It can be a very intense and dense period, with a lot of things happening at the same time. We wanted to convey that visually.

I really love the typeface, especially when the circular glyphs are animated. Can you speak a little bit about the development of this typeface?

There are quite a few typefaces out there that feature spirals in their glyphs. But all of those felt either too retro or too organic for this purpose. We were keen to be precise and playful at the same time–to simultaneously create something very constructed and quite dynamic. We made a few hand drawn sketches to find the general proportions and feeling. We also asked our friend Jürg Lehni, who created paper.js and the Scriptographer plugin for Illustrator back in the day, to create a small spiral tool for us. This made it easier and faster to draw very precise spirals with the parameters we needed for the various glyphs. We hope to extend the glyph set with lowercase and more punctuation later this year.

Could walk us through the printing process for the poster?

We used offset printing to produce the poster. This gave us access to radiant spot colors, which was essential for creating the vibrancy we were aiming for. The first step was to print the background layer and the big spiral in black and fluorescent red. The silver layer with all the typographic information cut-out was applied in the second step. This way the typography is displayed by revealing the first printing layer, thereby creating a vivid interaction of the overlapping elements.

Something I really admire in your body of work—and this year’s poster is no exception—is how layered it all feels. I mean this both visually and conceptually. Like a root system, we are taking in what is above ground, but it also hints to non-visible layers that are fun to unpack. Could you discuss the conceptual side of your process? What was the thinking behind this public program identity?

The deeper roots of our approach might be found in our latest fascination for the contemporary discourse around time. Today, many artists and writers are challenging the conventional Western idea that history moves in linear fashion. They are emphasizing the non-linear nature of time instead, thinking of history in loops, dialectics, time bangs, and spirals. For example, Ocean Vuong writes in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: “Some people say history moves in a spiral, not the line we have come to expect. We travel through time in a circular trajectory, our distance increasing from an epicenter only to return again, one circle removed.” We think many of those alternative notions of time are beautiful and fascinating, since they imply a more complex, long-term and intertwined relationship of humans, more-than humans, and the environment. In many ways, these concepts are counter-chronologies, challenging today’s prevalent version of standardized and linear time that serves efficiency, productivity, and a mainly economic perspective on progress and growth. These alternative, nonlinear views on time–some of them in the shape of a spiral–propose a less anthropocentric position, which might help us to synchronize ourselves with a world that is made up of multiple rhythms of being, growth, and decay.

Your portfolio has a striking visual range. Rather than following a set stylistic approach, you seem to generate a vernacular response to the subject matter of each project. What are the underlying continuities within your stylistically diverse body of work?

One underlying continuity within our work is our ongoing interest in multilayered narratives. Stories define who we are, sociologist Arthur W. Franke writes. They do so because they always “work on us, affecting what we are able to see as real, as possible, and as worth doing.” The aesthetics of each project develop from this and similar questions. What style communicates the story we want to tell? What tools do we need to use in order to create the aesthetics we envision? What production processes emphasizes our idea?

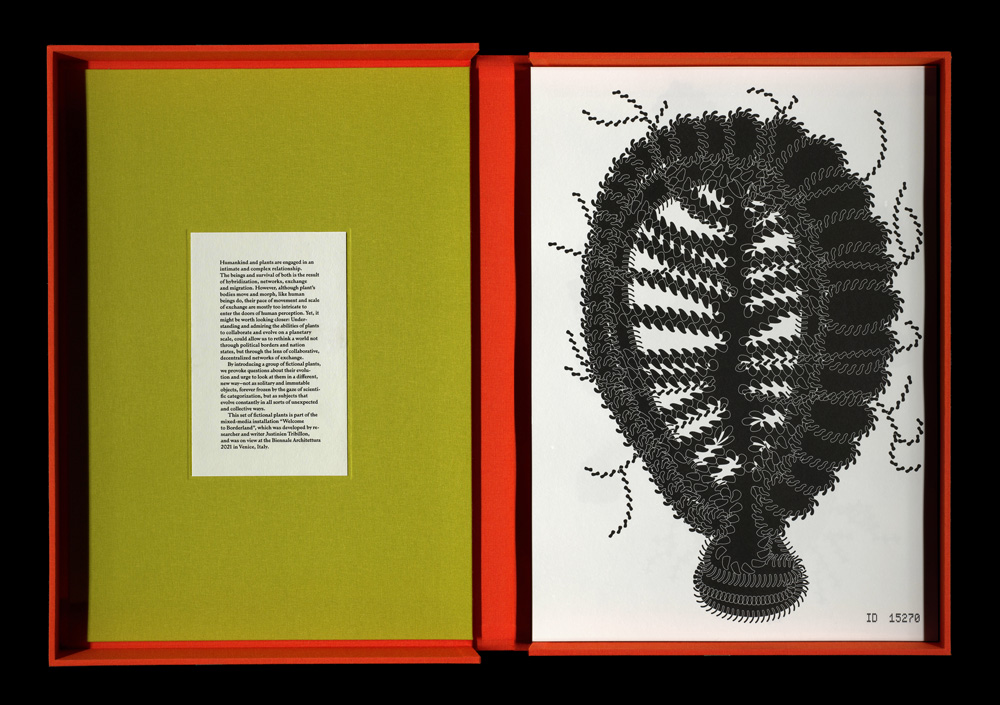

In the last five years, we have built manifold narratives, tackling issues ranging from migration, ecology, and interspecies relations to visual histories and design education. Working with various media—publications, websites, drawings, and exhibitions—we are interested in telling stories in an engaging, often multilayered fashion. Unfamiliar maps, vibrant visuals, symbols that expand and challenge the written language, photography, and illustration can coexist in our plots; they create rhythm, intertwine, and unfold unfamiliar perspectives. We tell stories by exploring, questioning, and transgressing the defined spaces of the discipline of Graphic Design while still staying committed to form, aesthetics, and craft.

One of the projects that brought your studio to our attention is the publication Migrant Journal , which ran from 2016–2019. You were not just the designers of this publication but also helped found it and were co-editors. Can you speak a little bit about what Migrant Journal was/is and what it meant for your studio?

Migrant Journal was a six-issue publication exploring the circulation of people, goods, information, ideas, plants, and landscapes around the world. Together with our contributors, we looked at the transformative impact this circulation has on contemporary life and spaces around us.

Our endeavor with Migrant Journal has been from the start to look at the world through the lens of these migratory processes—dealing with questions of belonging, national identity, cultural shifts, financial systems, but also landscape transformation, the weather, movement of animals, and global food networks. The idea was born in 2015 when the so-called migrant crisis in the Mediterranean Sea was seemingly the only topic in the news. We felt that there was a huge lack of in-depth information about the complexity of the issue, global interrelations, and the broader concept of migration. In a world of a polarized and populist political climate and increasingly sensationalist media coverage, we felt that it is more important than ever to re-appropriate and destigmatize the term migrant.

In order to break away from the prejudices and clichés of migrants and migration, we asked artists, journalists, academics, designers, architects, philosophers, activists, and citizens to rethink the approach to migration with us and critically explore the new spaces it creates. A printed journal provided a platform for multiple disciplines and voices to talk about an intensely interconnected world that creates a multitude of interdependent forms of migration.

The decision to produce a magazine, and not make a website or a book, was purposeful. We strongly believe that printed publications can create a reading experience that lasts longer than most ephemeral bits of information on the internet. As soon as it’s online, it’s lost in the stream of information, and we didn’t want this. Print is still the technology that ages better than any other carrier of information.

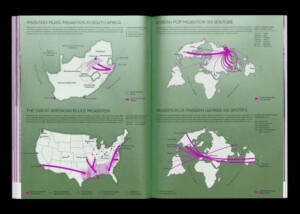

Maps are an integral component of migration. They are all about movement, territory, and space. So it felt very natural to use the technique of mapmaking as a narrative tool for our publication. Maps, as one major component of Migrant Journal, are woven into a diverse set of editorial formats, like essays, images, infographics, reports, and illustrations. Through the materiality of the object we were able to translate complex issues into a format that provides various points of entries in a multilayered manner.

It’s our founding project and has heavily shaped our way of working in many aspects of the practice. At the same time, it defined our studio profile and influences, until today, the projects for which we receive commissions.

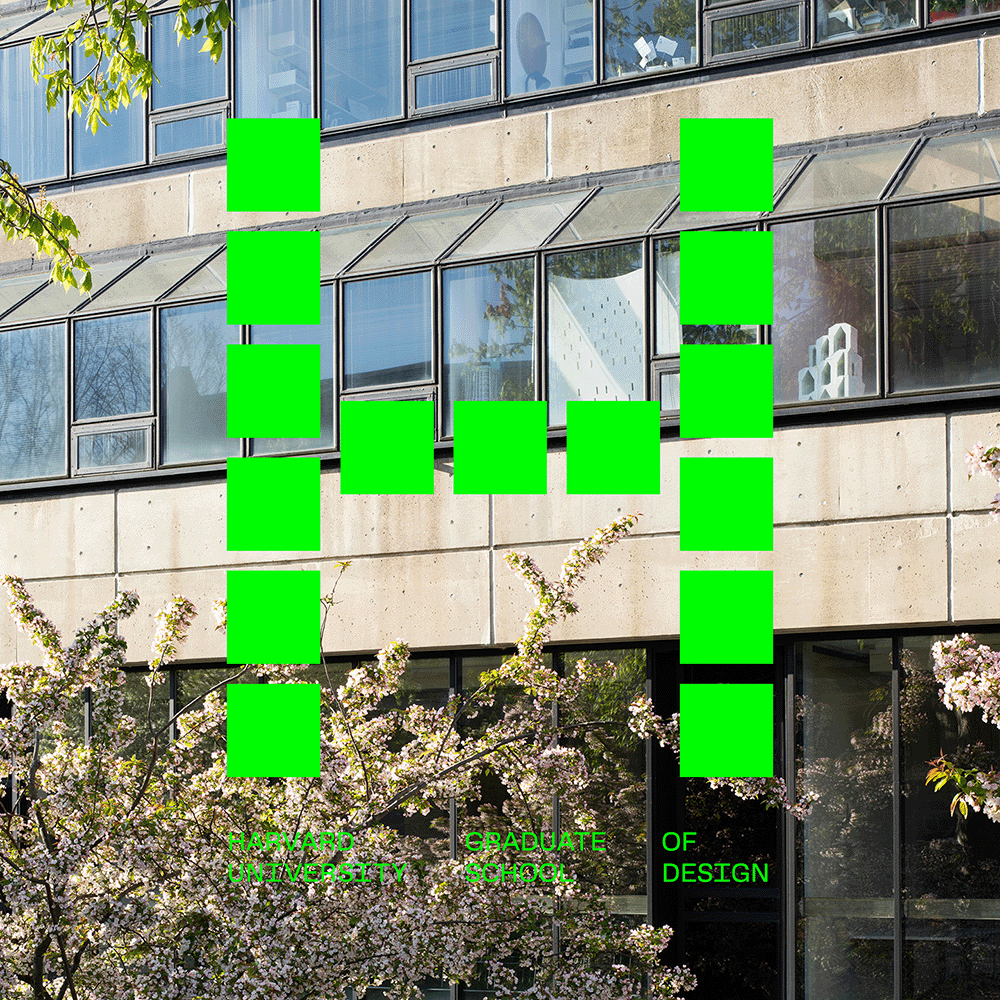

The Design Thinking Behind the GSD’s New Identity

A Language and a Tool

A visual identity is both a language and a tool. The Harvard Graduate School of Design needed an updated language of forms to communicate the School’s mission and values, as well as a tool to facilitate its pedagogical activities and day-to-day operations with a common set of visual standards.

Dean Sarah M. Whiting, in welcoming the GSD community back last year as Covid-19 pandemic restrictions eased, described the School as a place that synthesizes different and sometimes competing frameworks of knowledge. She challenged GSD students, faculty, staff, and affiliates to drive a public dialogue, bringing the knowledge produced at the School to the world.

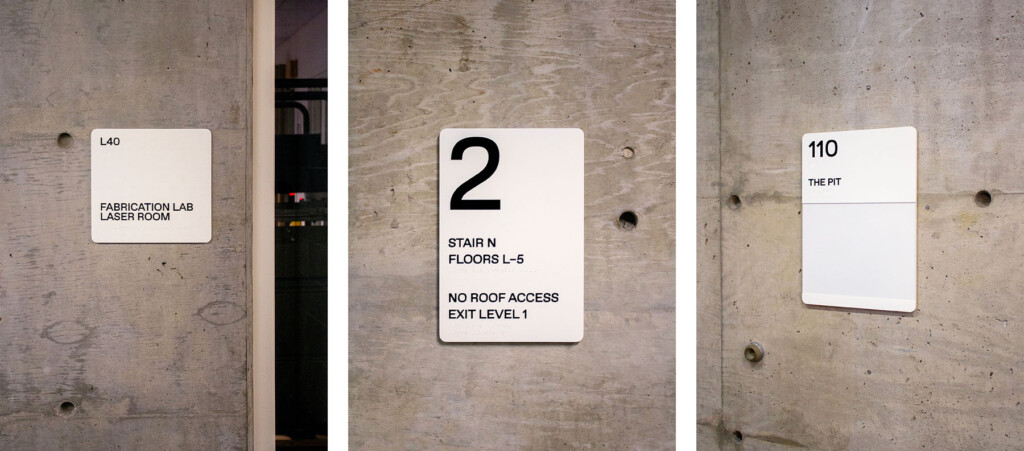

Conceived this way, the GSD is a dynamic center for learning and discourse. An identity that can help galvanize the breadth of the GSD community and convey the diversity of its ideas must be both adaptable and resilient. It needs to be functional, able to work with everything from large-scale physical signage to social media posts. In every context, the identity has to embody the critical design thinking at the heart of the School.

The University

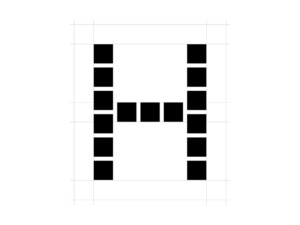

The GSD is rooted in the broader Harvard University community. Early versions of the School’s identity took the Harvard shield as a point of departure. Right at the turn of the 21st century, the GSD departed from this tradition—and set itself apart from other Harvard schools—by adopting the “Flying H”, designed by Nigel Smith.

The abstracted Harvard “H” projects the dynamic outlook of an educational institution devoted to fostering leaders in design, research, and scholarship.

The School

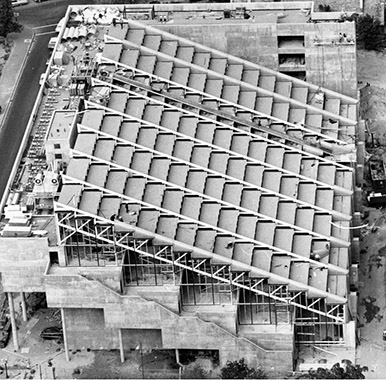

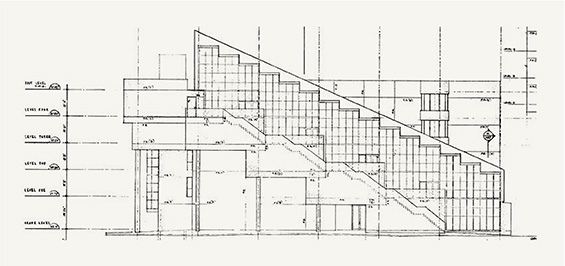

The heart of the GSD is our main building, Gund Hall. This is where the energy associated with learning, teaching, and study is most palpable. In turn, the Trays are at the heart of Gund. This iconic space facilitates the work that happens here.

John Andrews, the architect of Gund Hall, affirmed this importance through his design—the Trays were not part of his brief for the building’s design and are solely his invention. The Trays serve as the backbone of the building. They also define its distinctive form. The physical structure of the building is also the symbolic foundation of the School. In a sense, Gund Hall is a language and a tool: a visual identity expressed in the built environment.

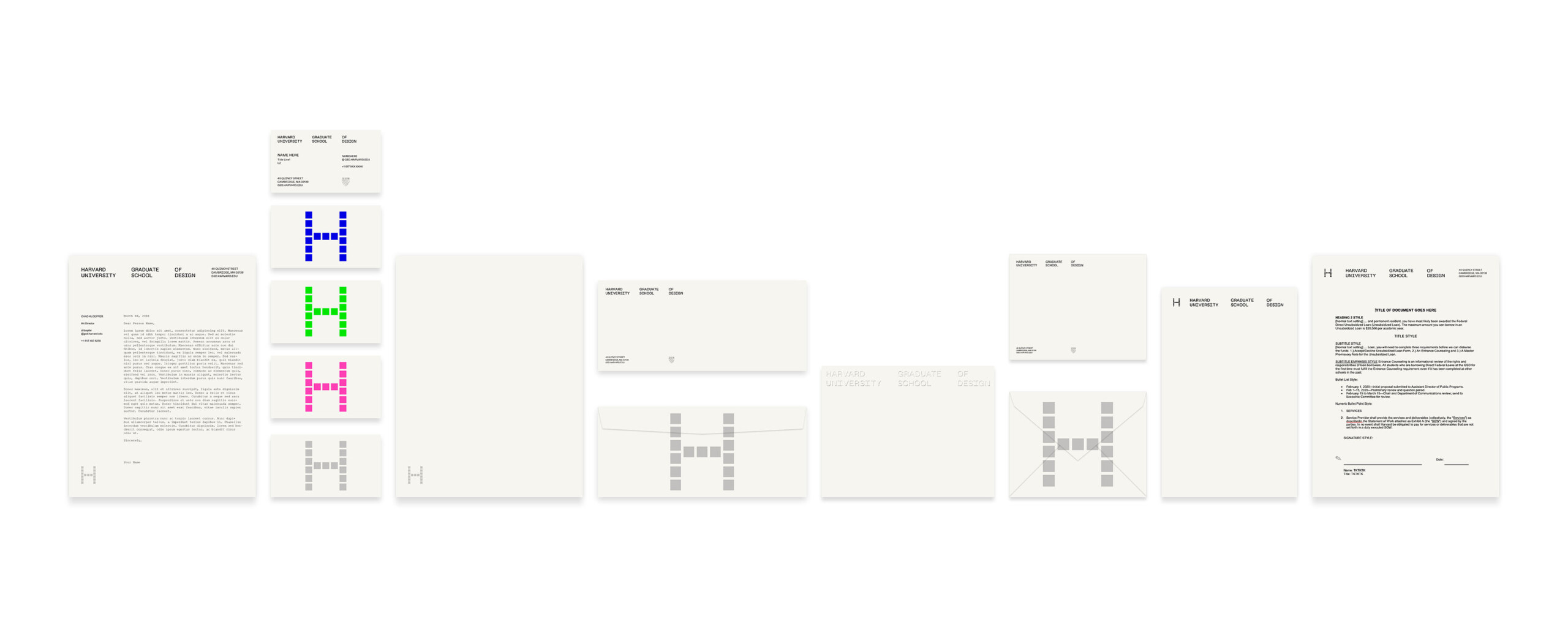

The Structural H

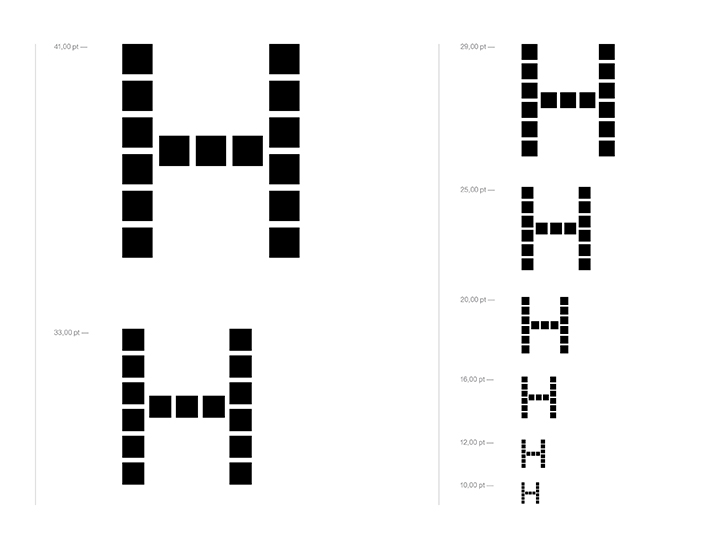

We took inspiration from Gund to develop the new GSD logo. The letter “H” immediately connects the GSD with Harvard. If we strip away the surface of the glyph, we reveal the underlying structure of the letter’s form and composition: its architecture. The letterform foregrounds the features of its own design and construction, just as Gund Hall does. The visual form, derived from self-reflexive inquiry, both embodies and represents the GSD’s pedagogical mission.

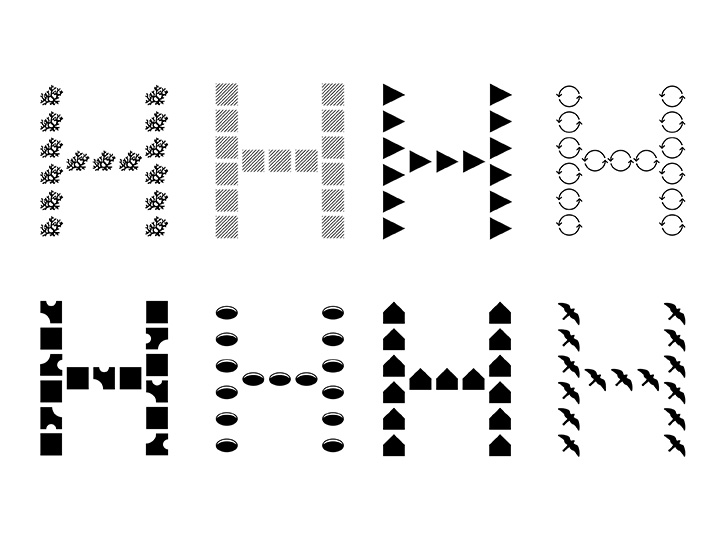

A Multiplicity of H’s

An institutional identity grows and changes over time. The GSD encompasses the multifaceted work that happens at Gund Hall. But the institution is bigger than a building. It is the network of people who put in the work—organizing, teaching, studying, building, communicating, and ultimately fashioning the School in their own unique ways. To be true to the GSD, the structure of the logo needs to accommodate a myriad of creative perspectives. A template of the “H” structure is available to students, faculty, and staff who are empowered to create their own versions of the wordmark.

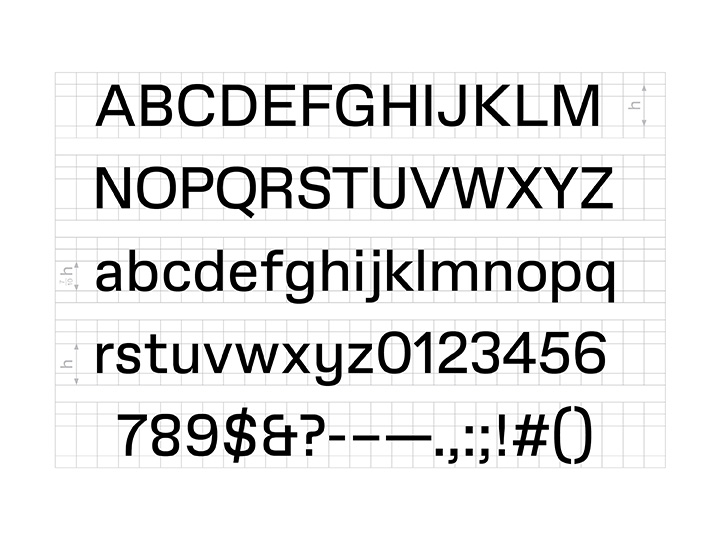

Typeface

GSD Gothic is both an aesthetic companion to our new logo and a unique means of addressing a wide audience. It needs to be legible in different environments, from signage that feels at home in Gund Hall to dense documents circulating in print or online. It is the workhorse of the identity.

Variable Font for the Digital World

The typeface will exist in two different formats. A traditional format has different weights and styles—that is, regular, italic, bold. GSD Gothic will also exist in a variable format, an approach to typography suited to the digital world.

A variable format does not have discrete styles; it can exist in any variable between a set of parameters. This version of the typeface is delivered not in files but in code. It can live on our website and within other digital assets, and it can be programmed to react to dynamic conditions of display.

A System

The logo and wordmark function as separate elements, each addressing different needs.

But sometimes they come together. The different elements of this system will be displayed throughout the GSD, online, and in the documents that GSD community members use to correspond with the world.

The Harvard Graduate School of Design embarked on its new visual identity in 2022. It was officially adopted in fall of 2022, and since then has been implemented in phases. The GSD’s art director, Chad Kloepfer, designed the new identity.

Ryan Gerald Nelson on Designing Iconic Typographic Moments

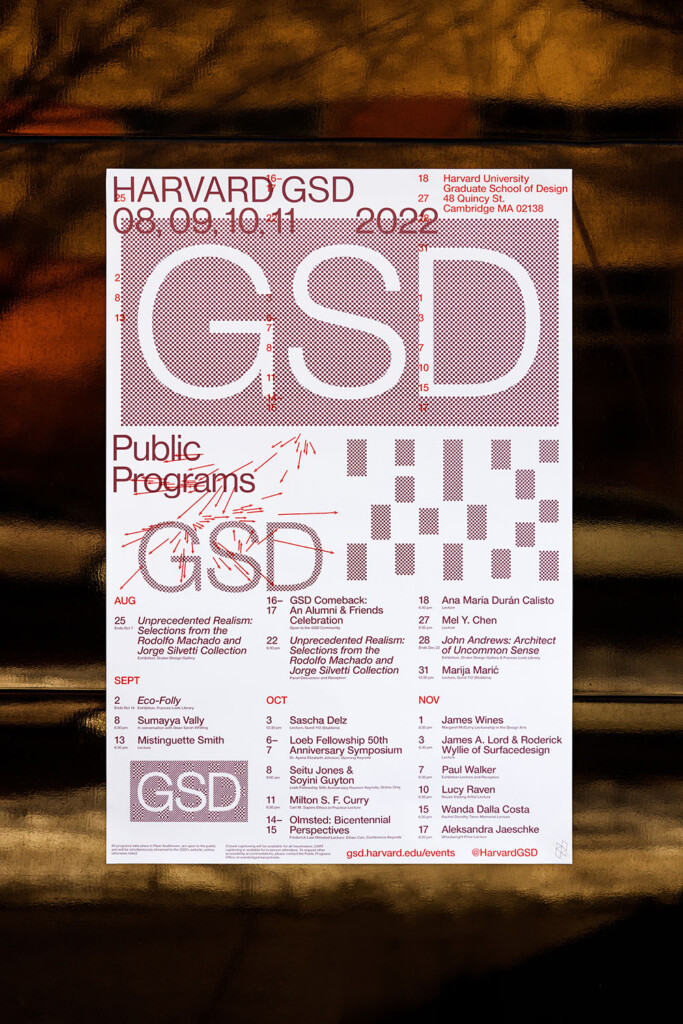

Within the work of graphic designer Ryan Gerald Nelson there is a persistent thread of experimentation. He experiments with images, typography, materials, and printing techniques, often manipulating all these elements at once. The compelling results range from the elegant and spare exhibition catalogue for Merce Cunningham CO:MM:ON TI:ME to the aggressive, overloaded posters he created for the Walker Art Center and Yale University. The attention to both big ideas and small details made his Studio Xee a perfect fit for designing the posters and related materials for the Fall 2022–Spring 2023 public programs at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). As we look back on the academic year, Chad Kloepfer, art director of the GSD, caught up with Ryan. The two met years ago when Ryan was a design fellow at the Walker.

Chad Kloepfer: We began discussing the past year’s public programs identity on a conceptual level, looking at how the project’s intellectual foundations could inform the design. Paige Johnston, associate director of public programs at the GSD, brought up The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (2013), a collection of essays by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney that draw on a radical Black intellectual tradition to critique academia. Moten and Harney write about ways to create the worlds you want to inhabit, outside of or adjacent to the existing world and its systems of knowledge. These are not easy concepts to formalize into a poster, but I wonder how, or if, Moten and Harney’s text ultimately fed into the final design?

Ryan Gerald Nelson: I did have some early moments of feeling a bit lost in all the potential ways and paths of interpreting The Undercommons and trying to land on certain ideas that I felt could propel my design decisions within the poster.

But as I dove deeper into the text I couldn’t help but notice the extent to which Moten and Harney’s observations and discourse feel so relevant to so many different spaces and aspects of society. A public programs and lecture series at a major university certainly felt to me like one of those spaces.

Ultimately, I felt like there was so much to glean from The Undercommons, and certain ideas from the book led me down a path that I wouldn’t have otherwise taken. As a graphic designer, that is something I always hope for in a project—some combination of collaborators, content, and reference material that expands my ways of thinking and making.

But to give some detail of how The Undercommons influenced certain design decisions of mine, we can look at how the authors define the idea of study. As Jack Halberstram observes in his introduction, Moten and Harney suggest that study is “a mode of thinking with others separate from the thinking that the institution requires of you.” Moten goes on to say that “It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice.”

I love this definition, and it’s clear to see how study is pervasive and already happening, and that we’re building a world through the acts of sharing space and ideas with one another (which is certainly something that the public programs and lectures at Harvard GSD become vectors for). So there’s an energy and potential in these notions that I attempted to capture within the poster through a sort of graphic/typographic density, overlap, and cross-pollination. The idea of study can be broad, but it prompted me to think about how I could use the design to reflect a sense of movement, momentum, a gathering of a chorus, a decentering, a deconstruction.

Something that attracted me to your work is that you are not exclusively a graphic designer. You also have a visual arts practice that runs parallel to your design practice. From the outside I can make formal connections between the two but I’m curious what the relationship of these worlds is for you?

These days the relationship is more separate than it has been in the past. Or at least in my conscious mind I’m always “switching” between the two: graphic designer mind and artist mind. Maybe that’s because these two worlds still, to this day, seem like oil and water.

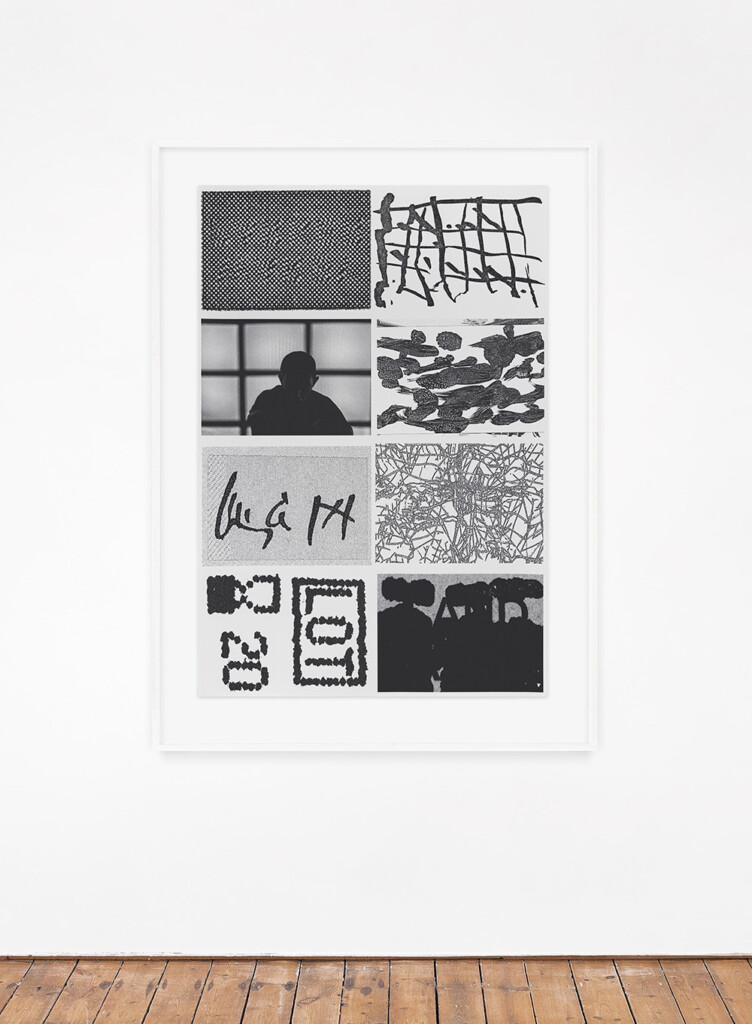

silkscreen print on archival paper, 30 × 44 in.

But if I start to examine things more closely, I can see a relationship between certain approaches or aesthetic sensibilities that I have in both my art practice and my graphic design practice. Like gravitating toward a certain formal starkness or austerity, or a level of high contrast (tonally, typographically, relationally between forms and elements), or even just a very granular level of detail.

The use of images is crucial to your work—both as a designer and visual artist—and you have specific ways that you use and manipulate them. We don’t have artworks or photographs in our poster, but you have almost treated “GSD” as an image and manipulated its presence in multiple cases. Can you talk about using images beyond their representational value?

I definitely seek out more formal and aesthetic ways to use images, or as elements that feel or act as texture or tone. Or maybe it’s just a desire to use them less conservatively. Having worked mostly in and around the world of contemporary art I’ve often bumped up against the preciousness or strictness that surrounds images. Rules like: no cropping, no altering, no going across a gutter, etc. I understand it of course, but it does make me want to rebel against those rules when the opportunity arises.

I’m also a big proponent of using type as image or type as texture. There’s a very type-centric or type-first mentality that’s pretty firmly embedded in the way I approach design, which definitely pushes me to be more inventive with type and to find certain type moves that can do some of the heavy lifting in terms of conveying ideas and content. That said, I’m often aiming to create typographic moments that feel very integrated (i.e., not just floating or slapped on top), and weighty, and iconic.

Repetition plays a large role in the posters, emails, and related materials for this year’s public programs. How did this come about as a visual device?

I started using repetition throughout the visual identity as a simple strategy to reference space, scale, and expansion, which of course felt very appropriate for a graduate school revolving around architecture and urban planning.

Repetition as a visual device most noticeably plays out within the poster where there are three relatively prominent “GSD” graphics that are descending in scale from top to bottom. I repeated the GSD “tag” not only to establish these different spaces or levels, but also to represent two ideas at the same time: the idea of ascension representing expansion or growth on the one hand, versus the idea of descension representing a zooming or zeroing in on the other.

The vertically stacked grid spaces on the poster also nest with or mirror this structure. Whereas the three “GSD” graphics are descending in scale from top to bottom, the vertically stacked grid spaces are ascending in their column structure from top to bottom starting with the one big “block” column on top, then the two “block” zones in the middle creating two columns, and finally the three columns of listings on the bottom of the poster.

The day numbers from the calendar are also repeated and overprinted on the top half of the poster. The core parts of the poster were already locked in this nesting, symbiotic structure, so I wanted to bring in a similar, connective gesture to reinforce the repetition. In this instance I felt that the overprinting red day numbers become more of a representation of time as a space, presence, or structure.

You have a wonderful sense for type and typeface choices. Even the simplest typeface, in the right hands, can be used to great effect. How do you go about choosing a typeface (our poster is set in Helvetica Neue) and then using it?

I love a simple typeface! To me there are some absolute classics that I would probably be happy to use forever. I feel fortunate that when I was first being introduced to typography that my instructors were showing me the work of a lot of amazing Dutch graphic designers. That had a major influence on me, and I definitely noticed the typefaces they used, the sort of calculated unfussy-ness of their approach to type, and even their loyalty to using just a handful of typefaces for all their projects, or even a single typeface.

Just some of the typefaces I’m thinking of are: Gothic LT 13, Grotesque MT, Univers LT, Akzidenz Grotesk, condensed cuts of Franklin Gothic, more obscure cuts of Times New Roman like MT or Eighteen, Gothic 720 BT, Pica 10 Pitch, Prestige Elite, AG Schoolbook, and of course Helvetica Neue, among many others.

As far as choosing a typeface goes, I like to keep that process simple as well. I think the width of the strokes are a major factor. Sometimes I’m trying to find stroke widths that feel in harmony with other elements like images, content, format, the proportions of the format, etc. But in other instances, it makes more sense for the stroke widths to have a lot of contrast or weight difference in comparison to the other elements. Lastly, I think the letters used in the main title of the design project play a big role in how I make my typeface selections.

With the uppercase letters in “HARVARD GSD”, I’m primarily looking at the “R” and the “G”: both great letterforms that I happen to find pretty irresistible when they’re typeset in Helvetica Neue. With a Helvetica Neue “R”, it’s the curve of the leg. It’s a super elegant curve with a slight outward taper down on the baseline that I think sets Helvetica Neue apart. With the Helvetica Neue “G”, it’s almost all about that downward spur in the bottom-right of the letterform that’s perfectly balanced and gives the “G” such an iconic stance.

Had the main title of this project not included an “R” and a “G”, I’m sure I would’ve chosen a different typeface. It all comes back to content and what you’re working with—even down to the letters being used.

I don’t imagine you have a traditional studio structure as a designer, but the desk-job portion of running a studio is not something they teach in school. Is there any kind of learning curve when it comes to practicing design for clients and what it takes to “manage” a studio?

I think there can be a fairly steep learning curve considering that being an independent or small studio graphic designer can often require you to possess so many graphic design adjacent skills. You might only be working on actual graphic design for 20 percent of the time during a project, while the other 80% of the time is dedicated to aspects like pre-production, editing content, communicating with collaborators and vendors, ensuring quality final production, etc. Like you mention, design schools barely and sometimes never teach these aspects of graphic design to students, but they’re obviously important.

These types of skills tend to live in the background which is probably why they go untaught in design schools and, frankly, are not even spoken about very often. But I wouldn’t trade them for anything simply because skills like these give me the confidence to handle just about any project thrown at me and allow me to focus more on the actual graphic design.

Strictly Typographic: Behind this year’s public programs posters by Harsh Patel

The Harvard Graduate School of Design’s art director Chad Kloepfer first came across designer Harsh Patel ’s work in two books: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog and Roman Letters by Evan Calder Williams (co-designed with Mark Owens). “They both felt as if they had landed in the here and now from a different era,” says Kloepfer. “It was hard to pin down a reference point and I was immediately charmed by the mystery and mood of it all.” It was in part due to these two exquisite objects that Patel was invited to design this year’s public programs posters, the second iteration of which will be unveiled today with the announcement of the spring semester’s public programs. Kloepfer and Patel sat down to discuss design practice and thinking in a world that’s pushed ever further into the digital sphere.

Chad Kloepfer: Coming into this season’s public programs posters, we were interested in pushing this project somewhere new, graphically. Can you talk about your entry into the process and the creation of this poster?

Harsh Patel: In our initial discussions, I suggested that the seemingly straightforward task of presenting this information could simultaneously express two different feelings about the second year of this pandemic. The first approach—reflecting how introspective everything sort of got, assuming you stayed inside—was to be pared down typography, in a kind of first-person singular voice. It would be laid out in dense, intricate grids with pragmatic but idiosyncratic typefaces like the original Futura. The second approach resonated more with me on a personal level, although it made for a far less practical working methodology. It’s a visual summary of the anxious barrage that we stepped into when we went outside. The public programs poster and all of the individual event posters are pastiches of these ideas.

I want to backtrack for a moment and ask: when you get a commission like this one—where there is not a lot of specificity to the brief—how do you begin to generate an idea or concept? Do you have a methodology that applies to a broad range of work, or is it a different working model, specific to every project?

Employing a set methodology could make things easier on myself, financially. Designers in the cultural sector with one of those in place really do manage assembly-line operations, especially in cities like New York. But, no: the problem-solution model isn’t something I believe in. There’s sometimes a financial incentive to commit immediately to a project like this and think backwards from a timeline or budget, but nowadays it’s more important to find a meaningful intersection, and to know when to say no.

Something I’ve always appreciated about your work is how it defies an easy definition. Almost every component of the work appears, to me, to be “found” for lack of a better word—which I mean as a compliment—and this poster is no exception. How did you arrive at the mixture of different typefaces used on the poster and how do you see that relating to the form of the lecture poster?

The typography is a capsule of street level commercial design—mostly the more vernacular kind that preceded today’s digital hypermarket. It’s the lettering on a paper cigarette package, or the logo on the underside of a plastic toy, or the made-to-order lightbox signage of a fried chicken shop. The only purely institutional component was the base typeface, Margaret Calvert’s New Rail.

Is there a strategy to the typeface(s) chosen for each lecture, or is it something you come at from a more instinctual place?

There’s no set strategy, other than going for lesser-known types.

The posters for the GSD are strictly typographic, but I’ve always been curious about your use of imagery; it’s quite specific. How do graphics and imagery find a place in your work?

In our profession, we typically receive photographic content pre-determined to fit within the image-and-copy relationship that defines most advertising design. We are usually granted some license to manipulate these images and attempt to subvert their meaning, as long as we remain within the bounds of the brief. This framework just isn’t that interesting to me. Graphic design shouldn’t willingly constrict its expressive possibility to that kind of messaging.

We also have more access to images and to the means of comparatively simple image making than ever before. In my intro courses, a ground concept is that we can articulate our aesthetic subconscious into visual form. It takes confidence and honesty to mine those depths and hone meaning into an individuated language or style. Making images is only meaningful or fulfilling if I feel that the translation from thought to expression is clear and concise, that the process is economically sensible in terms of time and resources, and that there’s ideological consistency in the bird’s-eye view.

We spoke briefly over Zoom about the relationship, or influence, of European design on US design. You were born in Nairobi and you currently work from both Los Angeles and New York City: how does both a sense of place and design’s many histories enter your work?

My upbringing in India and Kenya gave me a set of cultural experiences that shaped how I see myself amongst the world, generally. The American cities I’ve lived in as an adult have shaped my critical outlook and working methodology. Certainly my perception is that our daily practice hasn’t fully realized the value of biographical self-examination. It usually draws a freehand line to mid-20th-century European techniques that were engineered for workhorse production and systemic portability. As an immigrant and as someone who is interested in more intimate, or sensitive, ways of creating and appreciating, I protest this reality more than I accept it.

I find this approach very beautiful and refreshing—and it brings to mind the influence and power of “local” design histories. I feel like there is still so much to learn from both individual and local practices.

Yeah, there is. I’ve taught and talked about the history of graphic design for 10 years now. A public archive of that class material is slowly building up here

. Every example there asks questions about how and why things are categorized.

You work as both a traditional designer (taking commissions) and with self-generated content. How does either side of that coin inform the other, if at all?

Assuming I say yes to the right projects, then there shouldn’t be a marked difference. By sharing my editorial skills with my collaborators, and helping them identify some of their own visual amalgam, we usually find an authentic communication strategy.

I find being a graphic designer is to exist very much in a gray zone, which brings to mind the question of designer as editor, designer as artist. How do you see your role within the work or a given project?

The initial discussions—where you exchange values and decide what’s interesting, sustainable, and efficient—should take considerable time. Traditional studio structures operating on bureaucratic calendars can’t manage this as easily as someone with a completely solo operation like mine. My role is at first articulative, and then about devising expressive strategies.

Thank you, Harsh! We look forward to unveiling this spring’s public programs posters.