Pete Walker & the GSD: Nearly 70 Years of Connections

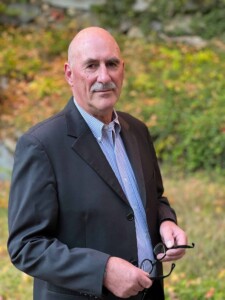

For almost 70 years, the landscape architect Pete Walker (MLA ’57) has maintained strong ties with the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), a relationship that has evolved alongside his career, from student to world-renowned designer and GSD benefactor. Since 2004, the Peter Walker & Partners Fellowship, conferred on Class Day, has supported travel for promising Landscape Architecture graduates.

Walker’s introduction to the GSD dates to the mid-1950s when he was a graduate student at the University of Illinois, studying with the landscape architect Stanley White. After his first term, Walker asked his professor what courses to take the next semester. White’s response? “Well, you’re not going to be here,” Walker recalled. “You’re going to be at Harvard.” Indeed, White had arranged with his former student Hideo Sasaki, then a GSD faculty member in the Department of Landscape Architecture, for Walker’s transfer.

Encouraging Walker’s move east, White had characterized Sasaki as a mastermind—an assessment Walker would soon share. “Sasaki saw the future in a way that I had never even imagined,” Walker says. “He gave this view of the world—an incredibly dynamic postwar view, talking about transportation, expansion of education, corporate expansion, urban expansion, world trade, airplanes. . . . I had never thought of landscape in those terms, likely because no one had really described it like that. And Sasaki was just beginning to.” Walker was thus exposed, though his time at the GSD and in Sasaki’s office, to a perspective that broadened landscape architecture’s reach to an urban scale.

Walker graduated from the GSD with an MLA in 1957 and, funded by the school’s Jacob Weidenman Prize, undertook his first trip to Europe to visit the continent’s historic gardens. After returning home, he continued to work with Sasaki, cofounding Sasaki, Walker, and Associates (eventually the SWA Group), which soon added to its initial location in Watertown, Massachusetts, an office in San Francisco, with Walker at the helm. He left SWA in 1983, establishing a small practice with his then-wife and partner Martha Schwartz (currently Research Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD). Since then, the firm has undergone a series of iterations culminating in Peter Walker and Partners, which now operates as PWP Landscape Architecture .

In the midst of celebrated design activity—including projects such as Harvard University’s Tanner Fountain (1984) and New York’s National September 11 Memorial (2011), with architect Michael Arad, and awards like the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Medal in 2004—Walker maintained a robust presence in the educational realm. While firmly ensconced at SWA in the mid-1970s, Walker returned to the GSD, initially as visiting critic and adjunct professor before serving as the acting director of the Urban Design program in 1976. (“My job was to replace myself,” Walker recalls. He succeeded, convincing his friend Moshe Safdie to become the new program head.) Walker then served as chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture from 1978 through 1981. He remained on the GSD’s faculty through 1991, after which time he moved on to UC Berkeley, his undergraduate alma mater, where he would lead the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning in the late 1990s.

Despite Walker’s move to the West Coast and the subsequent passage of time, his presence continues to resonate at the GSD, especially through his former students, three of whom have chaired the Department of Landscape Architecture: Gary Hilderbrand (MLA ’85 and current chair), Anita Berrizbeitia (MLA ’87), and George Hargreaves (MLA ’79). Contributing another layer of connection, sons David E. Walker (MLA ’92) and Jacob S. Walker (MDes ’24) have cemented Walker’s position as alumni parent.

Finally, Walker has expanded his relationship with the GSD by becoming a benefactor. In 2004, his firm established the PWP Fellowship for Landscape Architecture to provide “young landscape architecture designers [with] an opportunity to spend a concentrated period of time studying landscape design in various parts of the world.” The roots of this annual award rest in Walker’s own post-graduate experience—namely his Weidenman Prize–sponsored European travels, which exposed him firsthand to a historical component of landscape design that complemented the modern perspective introduced by Sasaki. Walker sees the PWP Fellowship as an opportunity for emerging designers to further broaden their global outlook. “For me, in a sense,” Walker says, these graduates “represent what design could mean in a changing world.” This year Walker will attend the GSD’s Class Day for the conferral of the PWP Fellowship.

In various capacities, Walker has witnessed—and played a discernable role in—the Harvard GSD’s evolution. And from his unique vantage point, Walker recognizes the diverse, mind-expanding views amassed at the GSD as an enduring gift for students and alumni alike, even long after they have departed campus. As Walker notes, “through family and close friends”—many former students turned colleagues—“Harvard has kept me in touch with these things.”

Niall Kirkwood Elected Member of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences

The American Academy of Arts & Sciences recently announced that Niall Kirkwood, Charles Elliot Professor of Landscape Architecture, has been elected a member of the honorary society in 2024.

Photo: Orah Moore.

Kirkwood is one of 250 new members—including Apple CEO Tim Cook, author Jhumpa Lahiri, and actor/producer/activist George Clooney—across 31 areas of expertise being recognized for their excellence and dedication to societal issues. “We honor these artists, scholars, scientist, and leaders in the public, non-profit, and private sectors for their accomplishments and for the curiosity, creativity, and courage required to reach new heights,” said President of the Academy David Oxtoby in the organization’s press release. “We invite these exceptional individuals to join in the Academy’s work to address serious challenges and advance the common good.”

According to its mission, the American Academy of Arts & Sciences was founded in 1780 by John Adams, John Hancock, and 60 other scholar-patriots to convene “leaders from every field of human endeavor to examine new ideas, address

issues of importance to the nation and the world, and work together ‘to cultivate every art and science which may tend to advance the interest, honor, dignity and happiness of a free, independent, and virtuous people.’” Previously elected members include Benjamin Franklin (1781), Charles Darwin (1874), Albert Einstein (1924), Margaret Mead (1948), Marin Luther King, Jr. (1966), Madeline K. Albright (2001), and Salman Rushdie (2022).

Induction ceremonies for new members will be held at the Academy’s campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in September 2024.

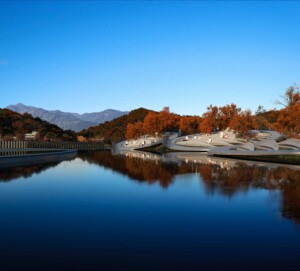

Kongjian Yu Featured in the New York Times for his “Sponge City” Approach to Urban Floodwater Management

Among the challenges posed by climate change, floodwater looms large. Today, cities grapple with regular inundations brought by intensifying downpours and extreme weather events, and conventional approaches to stormwater management—drainage pipes, concrete channels, and the like—are proving insufficient. Landscape architect Kongjian Yu (DDes ’95) offers an alternative solution, one that welcomes the water rather than fights to expel it. Yu calls this concept the “sponge city,” an idea that has been applied in 250 Chinese municipalities since 2015.

A recent New York Times article by Richard Schiffman, titled “He’s Got a Plan for Cities That Flood: Stop Fighting the Water,” details Yu’s sponge city approach and includes commentary by Niall Kirkwood, Charles Eliot Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Graduate School of Design.

In place of concrete drainage infrastructures, sponge cities embrace native vegetation, land formations, and constructed wetlands to slow and absorb excess water locally before it floods streets and subways. Such living landscapes offer additional benefits, as they simultaneously filter pollutants from surface water, provide habitats for wildlife, and offer recreational spaces for urban dwellers.

In September 2023, Yu delivered the Sylvester Baxter Lecture at the Graduate School of Design, “Adaptation: Political, Cultural, and Ecological Design—My Journey to Heal the Planet.” He discussed how his agricultural upbringing, experiences with the art of Chinese landscaping, and studies at the GSD inform his ideas about urban water management. The following month, the Cultural Landscape Foundation awarded Yu the 2023 Cornelia Han Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize (also known as the Oberlander Prize). Yu is founder of the Beijing-based firm Turenscape and professor at Peking University in Beijing.

Jungyoon Kim’s firm PARKKIM Wins an International Competition for a Floating Stage Development in South Korea

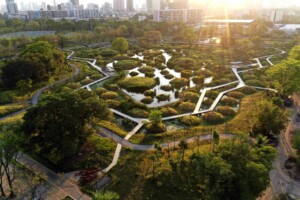

PARKKIM , the Seoul-based landscape architectural firm co-founded by Jungyoon Kim (MLA ’00), assistant professor in practice of landscape architecture at the GSD, with Yoonjin Park (MLA ’00), has won the international competition to design a floating stage for Suseongmot Lake in Daegu, South Korea. Proposals by the four firms invited to the competition, including PARKKIM’s “Suseongmot Floating Hills,” will be showcased in the first annual Suseong International Biennial this fall. The unique floating performance space, part of a multipurpose waterfront park, “aims to awaken the potential of Suseongmot and create a space for new programs, contributing to the revitalization of high-quality outdoor performance culture through the expansion of cultural infrastructure,” according to the competition guidelines released by the Suseong District. A panel of judges chaired by Kim Jun-seong of Hand Plus Architects Office evaluated the proposals by focusing on connectivity with waterside space, usability of space, and originality of design.

The proposed design by PARKKIM features eight sloped oval sections or “hills,” all interconnected by pedestrian walkways. Lushly landscaped with trees and vegetation, the open auditorium concept incorporates both fixed and lawn-type seating and accommodates an audience of 1,500. The platform and stage rest on a hybrid pile-slab structure, a combination of concrete and fiber reinforced polymers. Junya Ishimagi, a Japanese architect, won the concurrent pedestrian bridge competition that will land on the northern edge of the Suseongmot lake, about 100m apart from the Floating Hill stage.

Home to Korea’s largest music festival, the Daegu International Music Festival (DIMP), Daegu is designated as a City of Music by UNESCO. In a statement, Daegu Suseong-gu District Mayor Kim Dae-kwon said, “An excellent work was selected as the winner through an international design contest . . . We will build it as a cultural landmark that goes beyond the region and is world-class.”

In addition to Kim Jun-seong, the judges included Jin-wook Kwon, Yeungnam University; A-yeon Kim, University of Seoul; Jong-guk Lee, Keimyung University; Pil-jun Jeon, Daegwu Catholic University; Daniel Valle, Baye Architects; and John Hong, Seoul National University.

The Suseongmot Performance Hall and Bridge are scheduled to begin construction in 2025 and be completed in 2026.

Kongjian Yu Wins 2023 Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) has named Beijing-based landscape architect Kongjian Yu (DDes ’95) the winner of the 2023 Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize , a biennial honor that includes a $100,000 award and two years of public engagement activities focused on the laureate’s work and landscape architecture more broadly.

Yu recently delivered the Sylvester Baxter Lecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), “Adaption: Political, Cultural, and Ecological Design—My Journey to Heal the Planet.” His guiding design principles are the appreciation of the ordinary and a deep embrace of nature—even of its potentially destructive aspects, such as flooding. Yu’s thinking about “ecological security patterns” helped shape environmental protection efforts throughout China. And his promotion of the “sponge city” concept, which uses landscape to capture, filter, and store rainfall for future use and reduce flood risks, helped to spur the Chinese government to launch an ambitious sponge city campaign across the country and has gained global attention.

Named in honor of the late landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander (BLA ’47), the Prize awarded by the TCLF is bestowed on a recipient who is “exceptionally talented, creative, courageous, and visionary” and has “a significant body of built work that exemplifies the art of landscape architecture.”

The international, seven-person Oberlander Prize Jury selected Yu from among more than 300 nominations from across the world. In naming the 2023 winner, the Oberlander Prize Jury Citation noted of Yu, he is a “brilliant and prolific designer … [who] is also a force for progressive change in landscape architecture around the world.”

“He lives and breathes his conviction that landscape architecture is the discipline to lead effective responses to the climate crisis,” said TCLF President & CEO Charles A. Birnbaum.

Gary R. Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, adds that Yu is the “all-time greatest spokesperson for landscape architecture in China—a nation that needs environmental rescue on a colossal scale.”

Yu is Professor and founding dean of Peking University College of Architecture and Landscape, and founder and design principal of Turenscape . His projects have won numerous international design awards, including 14 ASLA Excellence and Honor Awards and seven WAF Best Landscape Architecture of the Year Award. Yu is also the author of over 20 books and more than 300 papers and is the founder and chief editor of the internationally awarded magazine Landscape Architecture Frontiers. Yu was elected International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2016 and received the IFLA’s highest honor, the Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award, in 2020, which celebrates a living landscape architect whose “achievements and contributions have had a unique and lasting impact on the welfare of society.”

The Cultural Landscape Foundation, founded in 1998, is a 501(c)(3) non-profit founded in 1998 to connect people to places. TCLF educates and engages the public to make our shared landscape heritage more visible, identify its value, and empower its stewards. Through its website, publishing, lectures, and other events, TCLF broadens support and understanding for cultural landscapes.

Remembering Claude Cormier (1960–2023)

I first met Claude Cormier (MDes ’94) when he approached me about being a teaching assistant position in my core studio course, in 1993. What impressed me most in our first meeting: his excitable voice, with an upward-sounding pitch, along with his genial and upbeat manner, which made me feel like I already knew this man. A quick wit, a quizzical intensity. I liked this about him. This was the convivial and always curious guy with whom I enjoyed a warm friendship over the past 30 years.

Claude passed away on September 15 this year, at age 63, after a four-year fight with a rare and uncurable form of cancer. His was a life too short, though it was filled with great drive and remarkable success. Claude was a rare landscape architect whose take on common design problems was nothing if not uncommon.

I will admit that fun has perhaps only rarely been a design motivation for me, but it was almost always this way for Claude. Once he established his firm in Montreal, he immediately made his mark with projects that came to him in the form of the typical kinds of urban problems we face everywhere—but his design solutions always defied expectations, and he was persuasive with concepts that were at times far-reaching though always precise in execution. Painted or wrapped trees, blue sticks, balls and cones, pink lights, umbrellas, fake stones—often ordinary things made dramatically unordinary. His admiration for and friendship with Martha Schwartz surely influenced this way of working, but Claude made it his own. He rather famously used to say he imagined himself as the love child of Martha Schwartz and Frederick Law Olmsted—another of his great influences, and a very different one at that.

Because of the sustained popular appeal of Claude’s work, he accumulated attention, enthusiasm, and recognition from far beyond the design community—including being appointed a knight of the Ordre National du Québec. But while he enjoyed peer recognition much like the rest of us, these things had little effect on Claude’s persona or his ego. What animated him the most was talking about the work, along with the jubilant embrace of his work by those who use the public realm spaces he and his partners and staff designed. Those of us who knew him will remember his love of fashion and design, his uncanny passion for art—high, low, fake, or real—and his unbending joyfulness in life. Amen. Yet his far larger legacy will remain those life experiences by the citizens who inhabit his comic, playful, and highly intelligent parks and squares every day.

A comprehensive account of Cormier’s life and career was written by Beth Kapusta and can be found at The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s website .

Alumni Spotlight: Kotchakorn Voraakhom

“Nature is changing, the climate is changing, and so we, too, need to change. We must understand that fixed definitions of nature from the past no longer apply in this era of uncertainty we are confronting. Climate change is causing cities to sink, and our current infrastructure is making us even more vulnerable to severe flooding. What if we could design cities to work with nature instead of against it?”

— Kotchakorn Voraakhom

Over the next couple of months, we are continuing to share conversations with several of our alumni, each of whom pursued different areas of study at the GSD and are now leading impactful careers in design.

We recently spoke with Kotchakorn (Kotch) Voraakhom (MLA ’06). Kotch is the founder and lead designer of the award-winning landscape architecture and urban design firm LANDPROCESS , where she’s working to improve Thailand’s public spaces and solve urban ecological problems through landscape architectural design. During the spring 2023 semester, Kotch is also a design critic in Landscape Architecture at the GSD and is co-teaching the Option Studio BANGKOK REMADE with Niall Kirkwood, Professor of Landscape Architecture and Technology and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs.

Kotch’s recent work spans a major urban ecological park at the heart of Bangkok and numerous innovative public landscape designs. She’s a Chairwoman of the Climate Change Working Group of the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA World) and a 2018 TED Fellow. The United Nations honored Kotch as a winner of the 2020 UN Global Climate Action Awards: Women for Results.

How did you hear about the GSD and what drew you to apply?

In Thailand, I studied landscape architecture at Chulalongkorn University. After graduating, I got a chance to work in the U.S. for a couple of years—which is quite hard to do as an international student, so I was very lucky. My landscape architecture profession started in the U.S. at Sasaki. My boss at the time, Alistair McIntosh, is on faculty at the GSD, and my professor Pornpun Futrakul MLA ’77 had graduated from the GSD, so I heard great stories about their experiences. The GSD seemed like a commonality among many people I looked up to, which made me think, “If I really want to be a great landscape architect, maybe the GSD is the answer.”

Was there a certain experience that you look back on as being helpful in finding the right practice?

A huge turning point was meeting my peers at the GSD. We were all questioning our place within the profession, and six of us founded an organization called the Kounkuey Design Initiative . It felt like my dream job to work for those in need of our services, rather than those who hired us for services they wanted. So, we wrote a proposal for a grant through the Penny White Project Fund —and we got it.

This was around 15 years ago—it’s remarkable, looking back. It wouldn’t have been possible without the platform the GSD provided; it wouldn’t have been possible without meeting the right people, [who became] my colleagues and friends.

Why is it so important to learn about the various cultures you’re serving when trying to come up with new design solutions?

We’re designing for humans, right? If we want to understand the needs of the people we’re designing for, we have to go and listen to them. We have to experience their culture, their food, their language—even if it’s just for a short period of time. Each unique site is so specific, and every project can vary dramatically depending on the location.

That’s why the option studios were such a great learning opportunity [at the GSD]. They gave us the chance to learn about another culture through real hands-on experience. Culture, climate, and people can vary drastically, and something that works in one country might not work in another. I feel that is what’s lacking in much of our practice. We talk to our clients, or whoever is paying us, but we don’t talk to the real stakeholders, who are the people being impacted by our work.

What goals and objectives did you have in mind when starting your current practice, LANDPROCESS?

There’s no “land process” without “people process.” I am very excited about the possible solutions for climate-vulnerable communities. I’m excited for the challenges that my team and I will face, even though they are very serious. For example, I’m from Bangkok; Thailand is [one of the 10 most] flood-affected countries in the world. Every year, our land sinks and goes missing because of rising sea levels. New buildings mean nothing if entire cities flood and sink in the near future.

The point that we are at now is “adapt or die.” The work that we are doing is helping to shift cities to a carbon-neutral future by prioritizing livelihood and utilizing neglected spaces.

Utilizing neglected spaces—can you expand on that?

Forgotten and unused spaces, like rooftops, can present opportunities to make a city more useful for everyone. My team at Thammasat University, working alongside the surrounding communities, has achieved this. We created the largest urban rooftop farm in Asia. The idea for this project was derived from the wisdom of landscapes of the past, when people used rice terraces to harvest the rain from the mountainous area.

Our goals for the project were to relieve flash floods and turn the urban heat island effect into clean energy. One solution [for flooding] was implementing a flood roof, equipped with rainwater tanks that are designed to flood, allowing water to flow up and down. Solar panels on the roof create clean energy, pumping out water from the retention pond, and gravity slows down the runoff to prevent flooding.

What would you say is the biggest worry or concern you have in your field right now?

The biggest global concern is climate change, by far. Thailand has tried to tackle its flooding problems by building higher and higher dams, but this is not the right solution because dams will eventually cause more problems.

There are 7,000 fishermen in villages along the coast of Thailand. These Thai people are not allowed to stay in their country, because their homes have been built into what’s now the ocean. These villages are in the most dangerous part of Thailand, next to Cambodia, so the people who live there have nowhere to go. The government has forced everyone in the villages to be displaced.

My work now is addressing these problems by helping villages design viable solutions and negotiate with the government. We were able to get the government to commit to a housing credit with UN-Habitat [United Nations Human Settlements Programme ]. Eventually, we helped the first village secure a permit to let us enter and address the [housing crisis]. This all happened right before COVID, and unfortunately, they only granted a permit for one local community. This problem is ongoing and is some of our most important work.

With these climate concerns, what do you see as the biggest opportunity for global designers today?

There should be more concern around how we manage resources. I feel that only thinking about structure in the traditional way of “fixing things” won’t get us very far in regard to sustainable design.

Nowadays, the world needs a nature-based solution, or an ecosystem-based adaptation, which is an open opportunity for landscape architects. I think we need to push for climate-focused design in all departments. If urban designers, planners, engineers, architects, and landscape architects all work more collaboratively, we will strengthen our cities in very significant ways.

Why is it important for designers to give back to the younger generations—whether it’s through teaching or being involved in the broader design community?

Education is best transmitted by human-to-human interaction. We need humans to teach and pass on their knowledge to other humans, to the next generation, whether it’s through experience, practice, or academia. The transmission of knowledge between generations is crucial. The next generation is full of energy and potential.

And for us as alumni, we are part of the GSD culture. Even if it was a brief two years, it was such an intense period that shaped who we are as designers. It’s important to be involved in the community as alumni because it’s such a gift that we’ve already received, and we get to share it with a new generation of designers.

How are designers leaders, and why is it important that designers continue to be leaders across industries?

When I graduated, I asked my professor, Niall Kirkwood, “Why did [the GSD] choose me as a student?” And he said, “Because of your potential to be a leader.” I had no clue what he was talking about because I didn’t want to lead anyone; I didn’t want to be the head of any defined organization.

Through my practice and experiences after the GSD, I started to understand the word “leadership” more and more. It’s not about a title or position, it’s about action and impact. It’s about what you care for. I’m a designer who cares for the future of humanity, my homeland, my people, and my community. That’s what “leadership’’ means to me.

You can learn more about Kotch’s work and leadership below:

How to Adapt to Climate Change | Harvard Magazine

How to transform sinking cities into landscapes that fight floods | TED Talk

Landscape Processes Discussion Series | Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts

Meet the Woman Behind Asia’s Largest Urban Rooftop Farm | Bloomberg Quicktake

Architect Fights to Keep Bangkok from Flooding | Bloomberg Quicktake

Fall Update—Department of Landscape Architecture

Dear Landscape Architecture Alumni,

I bring you greetings from Cambridge, where the autumn weather has been beautiful, and we are already past the midpoint of our fall semester. It’s my great pleasure to report that from where I sit, the mood in the school is positive and upbeat. Our “Back to School” gathering in early September hit the right notes with Dean Sarah Whiting and the program chairs sharing thoughts on the year ahead, followed by a Beer ‘n Dogs barbecue in the back garden for students, faculty, and staff. The relief among all parties upon a full and largely unmasked return was palpable. We also had a fantastic set of events around the GSD Comeback in mid-September, when returning alumni engaged in faculty-led “mini-courses,” witnessed our Dean Whiting honoring alums for achievements and service, and celebrated with friends at a raucous front porch party. This all occurred alongside our Alumni Council’s first in-person meeting in several years. And this momentum remains strong just after mid-semester reviews.

Many of you are aware of the Olmsted 200 events throughout the nation in honor of Frederick Law Olmsted’s bicentennial birth year. The department held a well-attended two-day event in September entitled Olmsted: Bicentennial Perspectives. Many notable speakers brought forward newly critical readings of Olmsted Sr.’s work and that of his successors. Professor Ethan Carr MLA ’91, of the University of Massachusetts Department of Landscape Architecture & Regional Planning, gave the Annual Frederick Law Olmsted lecture as keynote for the symposium. I am immensely grateful to Professor Anita Berrizbeitia MLA ’87 and most especially senior lecturer Ed Eigen for organizing this superb event.

We are all feeling the urgency of the climate crisis like never before. The extreme heat and drought this past summer here in Massachusetts was the worst I can remember in 40 years of practicing here. The deadly flooding in Pakistan left more than 1,700 dead and 33 million people impacted by the worst rains in decades. One-third of the country was submerged, and the damage is devastating. The Pearl River in Mississippi crested at 36 feet twice this year. That has happened only once before. Flooding and failed infrastructure intersected in Jackson, Mississippi, leaving the city without potable water for weeks. Forests burned in France and Spain this summer. And 18-foot surges from Hurricane Ian caused at least 119 deaths in Florida and adjoining states. Florida, in particular, will take years to recover.

Our faculty and students are directly addressing the urgent hazards of climate risk, the need to decarbonize our energy use and our material and construction practices, and the need to pursue the cause of environmental justice through design everywhere we can. To give you a palpable feel for this revolution in curriculum, I need only describe our current semester’s option studios, many of which have included international travel. In Guinea-Bissau, for instance, in West Africa, a studio with design critic Silvia Benedito MAUD ’04 is facing matters of food sovereignty in the face of extreme drought and fire risk. In the Mexican Altiplano with visiting design critic Lorena Bello-Gomez MAUD ’11 is leading a pursuit of the return to liquidity in the face of severe lack of water resources. In the Texcoco region of Mexico with Lecturer in Landscape Architecture, Montserrat Bonvehi-Rosich, students are tackling matters of polluted waste, drought, and land subsidence on a massive scale.

In Portland, Oregon, with visiting design critics Gina Ford MLA ’03 and Anyeley Hallova MLA ’03, students are working with an organization that treats children suffering from the traumatic effects of child welfare injustices and incarceration. In Iceland, with Surfacedesign design critics James Lord MLA ’96 and Roderick Wyllie MLA ’98, students are examining intelligent energy landscapes, individual responsibility, and bodily sensory experience—baths included. In Luxemburg, students are examining decarbonization of the entire territory with visitors Aglaee Degros and Stefan Bendix. With Sergio Lopez-Pinero, students are electing climate, ecological, or justice issues on sites of their own choosing in communities facing conflict. And a studio with design critic Danilo Martic is designing massive temporary settlements caused by forced migration, incarceration, natural or human disasters like those just mentioned, or religious affiliation. How very timely.

When I look at the option studios across all three departments, in fact, and at the coursework and final projects in the advanced design study programs and in design engineering, I see a correlation of issues and inquiries that is remarkable in its overlap of environmental, political, and justice drivers. We are using varying tools and modes of inquiry, asking differently framed questions, of course. But I would venture this: The time we are living in is marked by greater urgency in these questions, and I see that all students in all the programs in the school are facing them accordingly—to a degree, I would assert, that is unprecedented. I for one am glad for this alignment, and I trust we’ll find useful differences and productive overlaps. That excites me about the GSD at this time.

Because of former chair Anita Berrizbietia’s MLA ’87 excellent stewardship for the past seven years, I am working with outstanding faculty and amazing staff in the department. But we have had several retirements and a few departures in the past two years. My number one priority for this academic year is to secure additional design faculty for the department. We have four searches running concurrently, and I am deeply grateful for the leadership of Professors Niall Kirkwood and Ed Eigen, and to the many other faculty who are working on our behalf in these searches. In case it is of interest, you can see these positions described on the GSD website, on the Open Faculty Positions page. And, if you have recommendations for us, please don’t hesitate to be in touch.

We are gearing up for our first alumni gathering at the ASLA Conference in a few years, this time in San Francisco, on Saturday, November 12th. I look forward to seeing many of you there and at other events over the weekend. Please introduce yourselves to our nine student members who are traveling to the conference with financial support from the department!

I welcome hearing from you whenever you are moved to reach out. Thanks for paying attention to the department!

With my warmest wishes.

Sincerely,

Gary R Hilderbrand FASLA FAAR he | him

Principal

Reed Hilderbrand LLC | 130 Bishop Allen Drive Cambridge MA 02139 | 617 923 2422

Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture | Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice

Harvard University Graduate School of Design | 48 Quincy Street G312 Cambridge MA 02138 | 617 495 2367

Summer Reading 2022

Looking for something design-related to read this August? In this list of recent publications by GSD faculty, alumni, and students, you can find everything from a deep dive into cross-laminated timber to a murder mystery set during a design competition.

John Ronan (MArch ’91) recently published Out of the Ordinary (Actar Publishers, 2022), showcasing the firm of John Ronan Architects and its spatial-material approach to architecture.

Stanislas Chaillou (MArch ’19)’s Artificial Intelligence and Architecture: From Research to Practice (Birkhäuser, 2022) explores the history, application, and theory of AI’s relationship to architecture.

Bert De Jonghe (MDes ’21, DDes ’24) examines the intense transformation of Greenland through the lens of urbanization in Inventing Greenland: Designing an Arctic Nation (Actar, 2022). The book is based on De Jonghe’s MDes thesis, which was advised by Professor of Landscape Architecture Charles Waldheim.

Verify in Field (University of Chicago Press, 2022) is the second book from the firm Höweler + Yoon, founded by Eric Höweler (associate professor in architecture) and J. Meejin Yoon. It features recent designs by Höweler + Yoon, including the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia; a floating outdoor classroom in Philadelphia; the MIT Museum; and a pedestrian bridge in Shanghai’s Expo Park.

Blank: Speculations on CLT (Applied Research + Design Publishing, 2021), by faculty members Hanif Kara and Jennifer Bonner, explores the history and future of cross-laminated timber as a building material.

The Kinetic City & Other Essays (ArchiTangle, 2021) presents selected writings from Rahul Mehrotra, chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design and John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization. Mehrotra writes about the concept of the “Kinetic City” (as opposed to the “Static City” conceptualized on many city maps) and argues that the city should be seen as “patterns of occupation and associative values attributed to space.”

Looking for fiction? Check out Death by Design at Alcatraz (Goff Books, 2022) by Anthony Poon (MArch ’92). Described by LA Weekly as “The Fountainhead meets Squid Game,” it’s a mystery about architects being murdered during a competition to design a new museum at Alcatraz.

Photographer Mike Belleme and landscape-urbanist Chris Reed, professor in practice of landscape architecture at the GSD, collaborated on Mise-en-Scène: The Lives & Afterlives of Urban Landscapes (ORO Editions, 2021). It includes case studies of seven cities: Los Angeles, Galveston, St. Louis, Green Bay, Ann Arbor, Detroit, and Boston. Reed describes Mise-en-Scène as “a collection of artifacts and documents that are not necessarily intended to create logical narratives, more intended as a curated collection of stuff that might reverberate . . . to offer multiple readings, multiple musings, multiple futures on city-life.”

What makes an environment “responsive”? Responsive Environments: An Interdisciplinary Manifesto on Design, Technology and the Human Experience (Actar, 2021), from the GSD’s Responsive Environments and Artifacts Lab (REAL) and co-authored by Associate Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology Allen Sayegh, Stefano Andreani (MDes ’13), and Matteo Kalchschmidt, uses case studies to examine our “technologically-mediated relationship with space.”

Formulations: Architecture, Mathematics, Culture (MIT Press, 2022) by Andrew Witt, associate professor in practice, draws from Witt’s GSD seminar “Narratives of Design Science” and examines the relationship between mathematical calculation systems and architecture in the mid-20th century.

Work in Progress: Sijia Zhong’s heritage site in Lima, Peru

Sijia Zhong (MLA I AP ’23) describes her final project for the option studio “Transversal Grounds: Engaging Infrastructure, Landscape and Heritage for Lima’s New Urban Commons” led by Sandra Barclay and Jean Pierre Crousse, spring 2022.