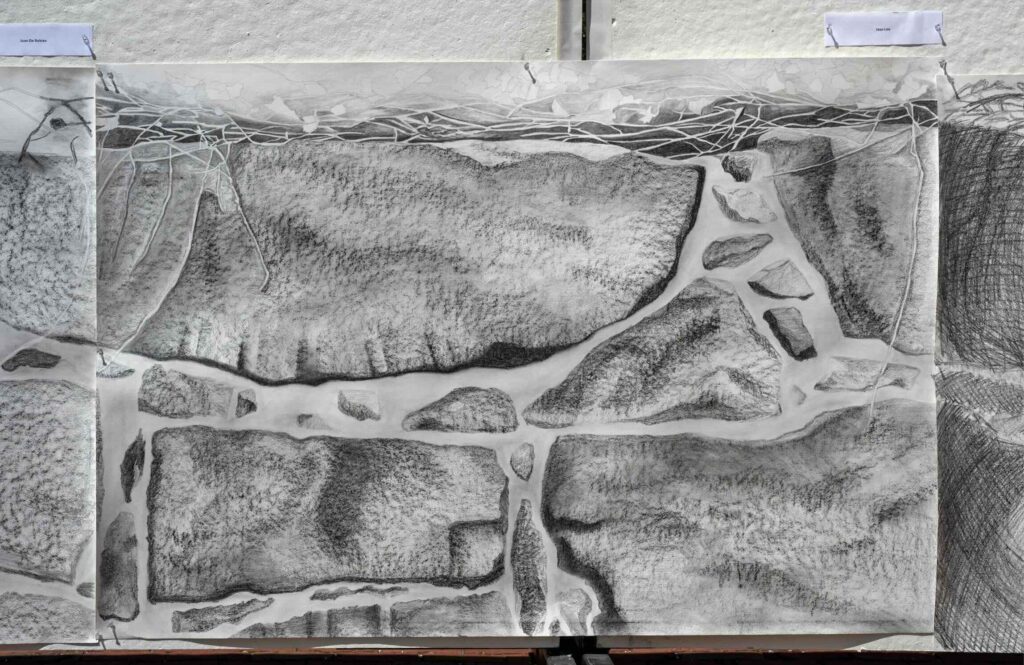

Spanning the length of Gund Hall’s sunny back patio stands a life-size black-and-white drawing of a stone wall, a cluster of students and critics squinting to assess its merits. This is the final review for Ewa Harabasz’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) course “Drawing for Designers 2, Human Presence: Appearance in Natural and Built Environments.” Students spent the semester observing closely and developing drawing techniques, capping off their work with the final collaborative stone wall project. Each student created a single frame 1:1 scale drawing on large sheets intended for watercolor—bumpy and uneven, creating more texture—which were then pieced together to create a continuous wall.

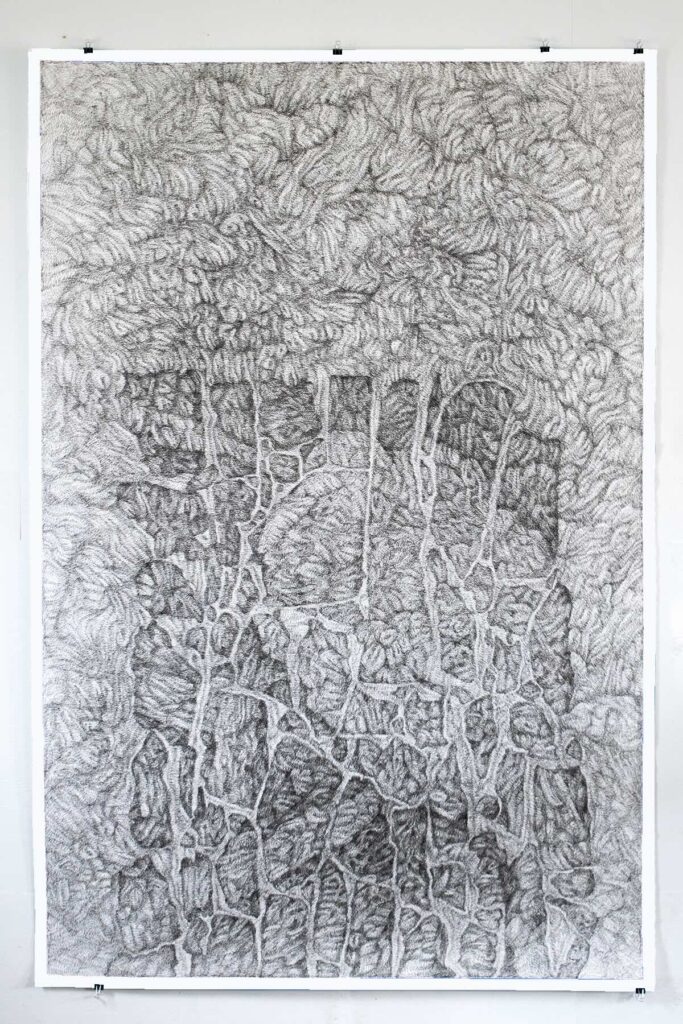

The range in styles that students developed this semester is evident in the shifting image of the whole from section to section. Tosin Oshinowo , a practicing architect and 2024–2025 Loeb Fellow at the GSD who was enrolled in the class, aimed to capture the “materiality of the stone,” she said, “without copying its patterns of darkness and lightness.” Junye Zhong (MLA ’25) relied on the texture of the paper and the bumpy tack board on top of which it was created to layer texture and strong contrasts, emphasizing the cuts in the stone. One student captured in meticulous detail the ivy at the top of the wall; another portrayed the patches of sunlight on the stones, encouraging the eye to move across the drawing.

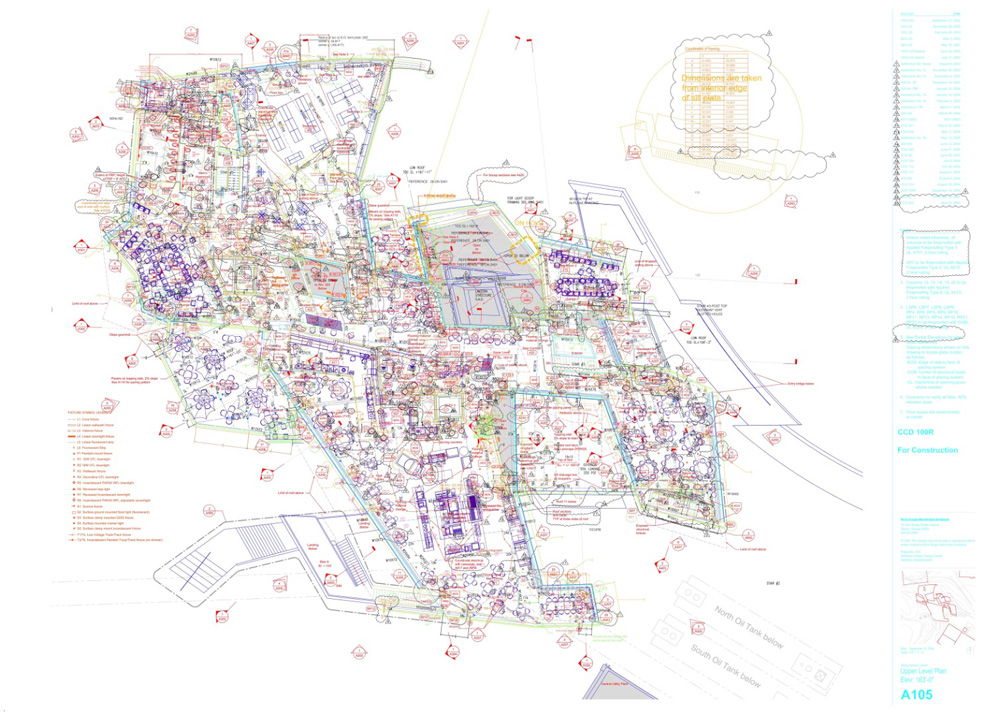

The project is the culmination of what Harabasz defined as a semester-long focus on “an expressive and playful supplement to computer-based labor.” Because architecture and design students inevitably spend hours working with various software systems that help them realize their designs, meticulously mapping out structures and landscapes on computer screens, said Harabasz, it’s equally as important that they develop their creativity and drawing skills.

“I want students to gain sensitivity and imagination,” she added, “and to strengthen their perception of the human body and architectural space and design.” She noted that the skills they develop by observing closely and learning to draw will enrich their work across the span of their careers.

Harabasz is a working artist who hails from Poland. Her drawings, paintings, and mixed-media projects are part of the permanent collection of the National Museum in Poznań, Poland, and have been exhibited in museums around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in Vaasa, Finland and the Kulturzentrum bei der Minoriten in Graz, Austria. Much of her work is created in large-scale formats, and deals with the violence of war and domestic abuse. Her recent series, “Icons,” for example, features stark photographs of people in the midst of conflict and grief, set on top of gold-leaf backgrounds. The images are reminiscent of medieval portraits of saints, the Madonna, and other religious figures, perhaps inspired in part by her work, earlier in her career, restoring paintings and frescoes in Poland and Italy.

This semester’s work in “Drawing for Designers 2” began with charcoal drawings. Harabasz asked students to home in on an emotional experience, gathering photographs to prompt memories, and to use charcoal in an “additive/subtractive process”—layering it onto the page as a gray base, and then erasing it to create highlights. The subject matter students chose to focus on ranged widely. Oshinowo explained that she had used charcoal in the past, “but never for abstraction.” In composing an image of a braid, she appreciated the challenge to approach the project with a different aesthetic in mind. Sabrina Madera (MArch I ’25) used the assignment to reveal to the group a recent surgery. “I felt I had to show the drawing publicly,” Madera explained. “Drawing the self-portrait forced me to have it out there.”

To offer more insight into the artistic process, Harabasz invited Polish abstractionist Urszula Śliz , PhD, to speak with the class from Poland, via Zoom. Śliz’s work, in mediums from drawing and painting to sculpture and collage, has been exhibited in museums around the world, including the Pavilion of the Four Domes Wroclaw Poland, the Nowich Museum UK, and many other cultural institutions in Europe.

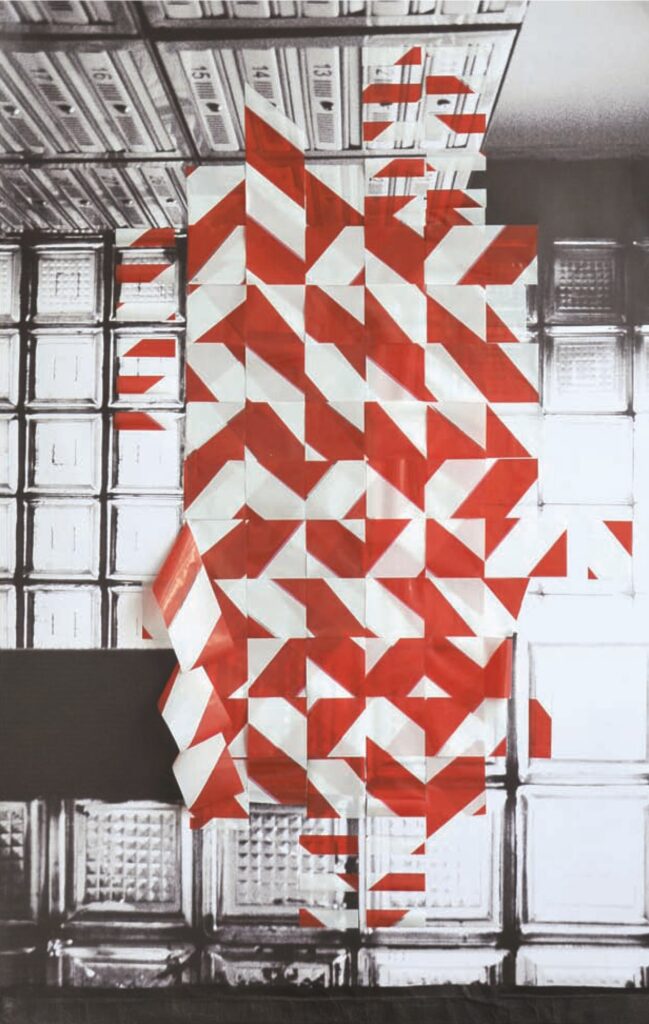

For the last ten years, she’s been working on “Transposition,” a series of collages made from her own photographs of everyday materials, such as construction tape. In one collage, the tape, with red, pink, and white stripes, is criss-crossed over flowers fallen on the ground. Viewers might make their own associations—for Śliz, the red and white make her think of her Polish roots—but, she says, the tape creates its own random shapes and forms, and the photograph serves to re-process the large-scale collage. Part of her inspiration, she explained, was the first known photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras (1826 or 1827) by Nicéphore Niépce, which, she says, transforms the black-and-white rooftops and buildings into abstract forms, estranging the houses from reality—abstract art. Śliz walked students through her process so that they could think about their own place in the art world, sources of inspiration, and how their own work might evolve across mediums.

As Harabasz instructs students on how to quickly and accurately reveal what they see, she also encourages them think about perspective and form in public contexts. Each semester, she and her class install collaborative, mind-bending spatial experiences on the fifth floor of Gund Hall. This winter, their black-and-white optical illusions were made by painting stripes and laying down tape to change the perceived shape of the walls and floors: Here, a new door appears. There, a bulge pushes out. A blue cat perches at the top of wall, playing with a spool of strings. Step to the left or right, and it splits apart on a corner. The installation invites a sense of play, and engagement with other students, faculty, and staff in the space.

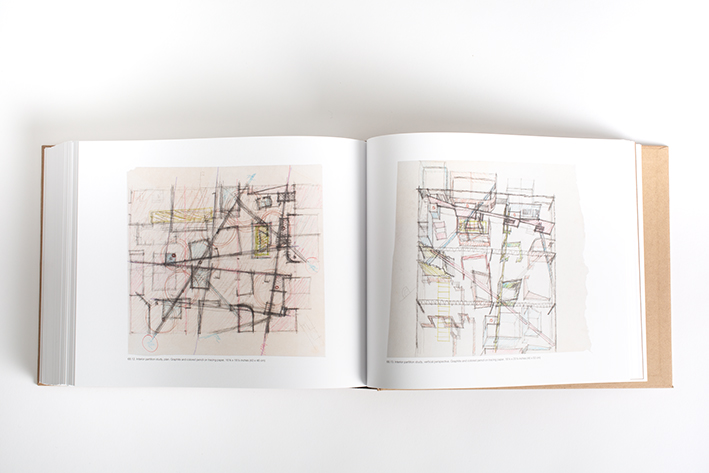

For the stone wall critique, several former students of Harabasz’s returned to share their insights. Paul Mok (MArch I ’18) a New York–based architect and artist who was named 2024-2025 GSD Alumni Mentor of the Year , showed the class an in-process drawing that he created using a technique he developed back in 2017, during an independent study with Harabasz (one of four courses he took with her). He’s completed two other highly detailed pen and ink drawings with the same methods, starting with marking the page with unplanned strokes, and then slowly filling to make the image.

“We always ask design students what their concepts are,” he explained, “and critique whether their designs are justified by their rationales. But what about intuition? I started this process of putting random strokes on paper without any preconceived ideas.”

For Mok, drawing is about “letting the mind wander,” an internal counterpoint to his work as an architect creating well-planned structures for others to inhabit. Similarly, two of Harabasz’s former students, Yuetong Li (MDes ’25) and Eva Cao (MDes ’25), spoke to the importance of the drawing classes they took at the GSD in developing their ability to “look not just at one part of an image,” said Li, “but to see the picture as a whole.” Cao appreciated the sense of narrative she developed in the course, combining image and text. They both found that drawing by hand is a useful tool, in addition to digital drawing.

Harabasz argued that developing their hand drawing skills grants designers the power to more clearly share their vision with others, and, perhaps even more importantly, to express who they are and what they value: “How do you view the world? What’s important? What do you see first, and second? How do we push the viewer to read the image as we want them to? This is what I teach.”