Five months after California wildfires killed 29 people and devastated neighborhoods in Los Angeles and surrounding areas, three Graduate School of Design students interned at the Southern California offices of landscape architecture and urban design firm SWA , to learn how to leverage design for fire prevention and remediation. Facundo Soraire (MUP ’26), Enrique Lozano (MAUD ’26), and Eleanor Davol (MLA ’27) spent six weeks learning about complex issues around fire risk, prevention, and remediation, and generated proposals for parcels that sit at the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) , where human communities meet undeveloped land and fire risks run high. This was the most recent of many collaborations between the firm and members of the GSD.

This summer’s program built on research undertaken by Jonah Susskind (MLA ’17), SWA director of climate and sustainability. Over the last decade, he’s conducted extensive research and taught a series of summer programs at SWA on the connections between climate change and fire risk, and how people and communities can best prepare, resulting in his book, Playbook for the Pyrocene , winner of a 2025 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) merit award in communications. Susskind writes that large segments of the population are moving to city outskirts. While residents once appreciated the suburbs for their access to nature and recreation, now, what draws them is the more affordable housing available further from the city due to “NIMBYism and local zoning restrictions.”

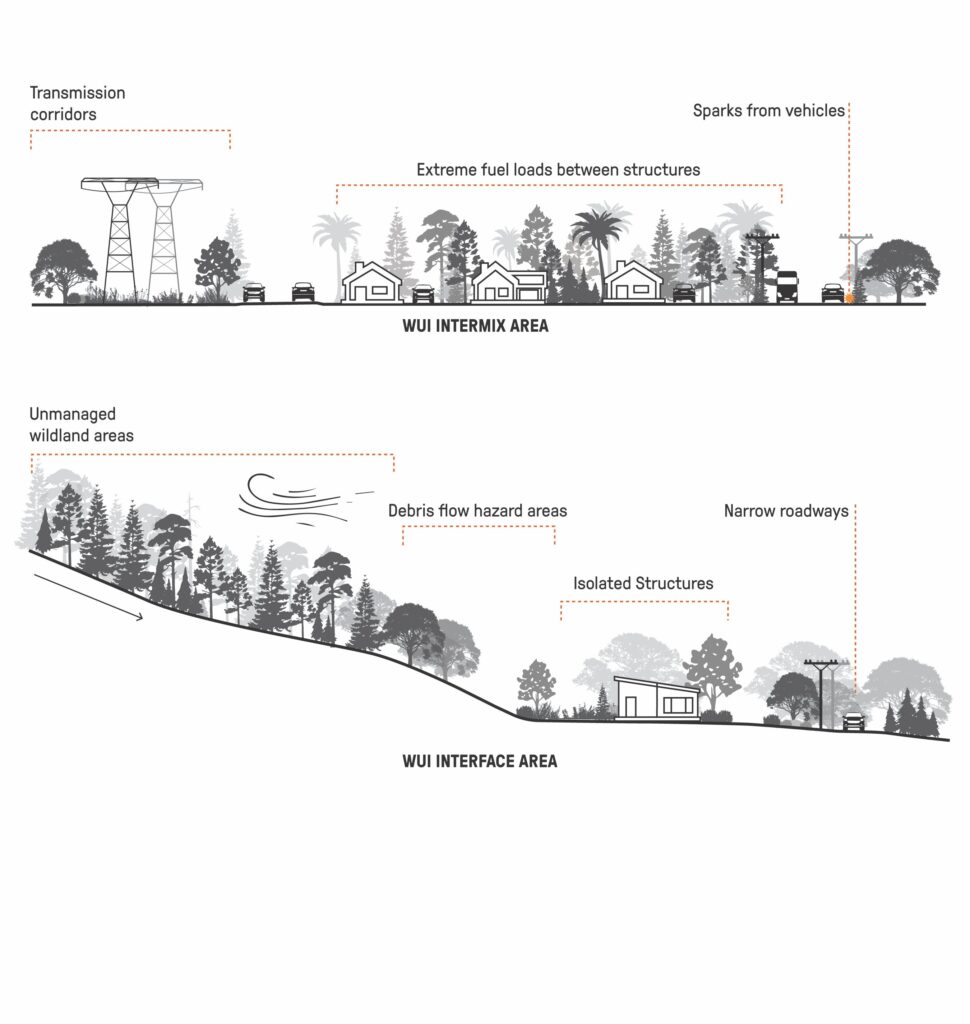

Thus, more and more people are seeking out homes in the WUI, which, because of the dire need for affordable housing, is growing by about 2 million acres per year

. Almost 100 million people in the US, Susskind notes, live in the WUI. This zone is especially vulnerable to wildfires as it’s often populated by “woodpiles, propane tanks, trees and shrubs, roof and gutter and deck debris,”[i]

as well as housing materials that may be especially vulnerable to fire. Susskind writes that, “[d]uring the past three decades, more than 80% of California’s fire-related structure loss has occurred in these high-risk zones.” Millions of people are likely experience the losses inflicted by ever more powerful wildfires.

Planners must “balance affordable housing with environmental conservation,” explains Susskind, especially because “the minute you get into the WUI, you also come up against entrenched histories of environmental conservation.” Susskind argues that suburban land use planning hasn’t changed much since the 1930s, and we need a new “suburban design ethos” that would allow for those communities to be “better resourced” in the face of fire risks and other climate change impacts.

“This is a design and planning challenge as much as it is a policy and economic challenge as much as it is a social and equity challenge,” he noted.

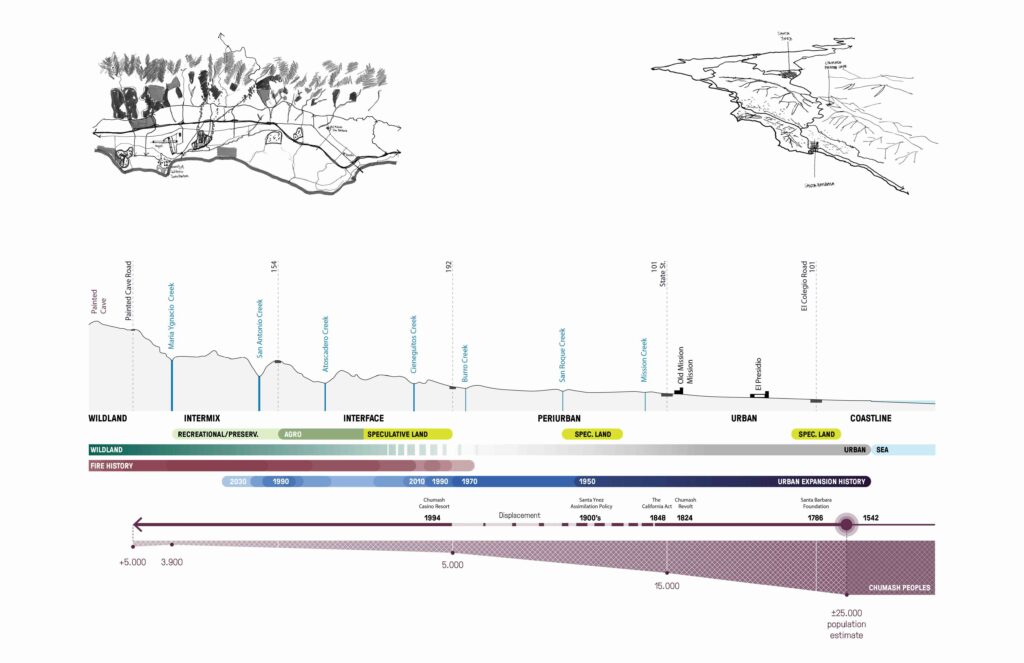

Each of the students in this summer’s cohort focused on a different aspect of wildfire prevention and remediation. Soraire, for example, envisioned a Community Land Trust (CLT) that would be led by the Santa Ynez Chumash tribe NGO, the local Indigenous nation, in support of co-governance and land stewardship that centers on the nation’s ancestral knowledge, including fire management techniques. The project includes affordable housing for the community.

Soraire took inspiration from his home province in Argentina, Jujuy, which borders Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, and is known as the “lithium triangle,” a mining territory. He investigated questions around land use, extraction, and the role of Indigenous voices in shaping land use. He started by mapping pre-colonial histories around Santa Barbara. Because several communities live in the region, “governance fragmentation and jurisdictional boundaries exacerbate fire risk.” His proposal, therefore, creates a central infrastructure for the many agencies already working in partnership with the Chumash, to share ideas and resources and center the nation’s presence and leadership on the land.

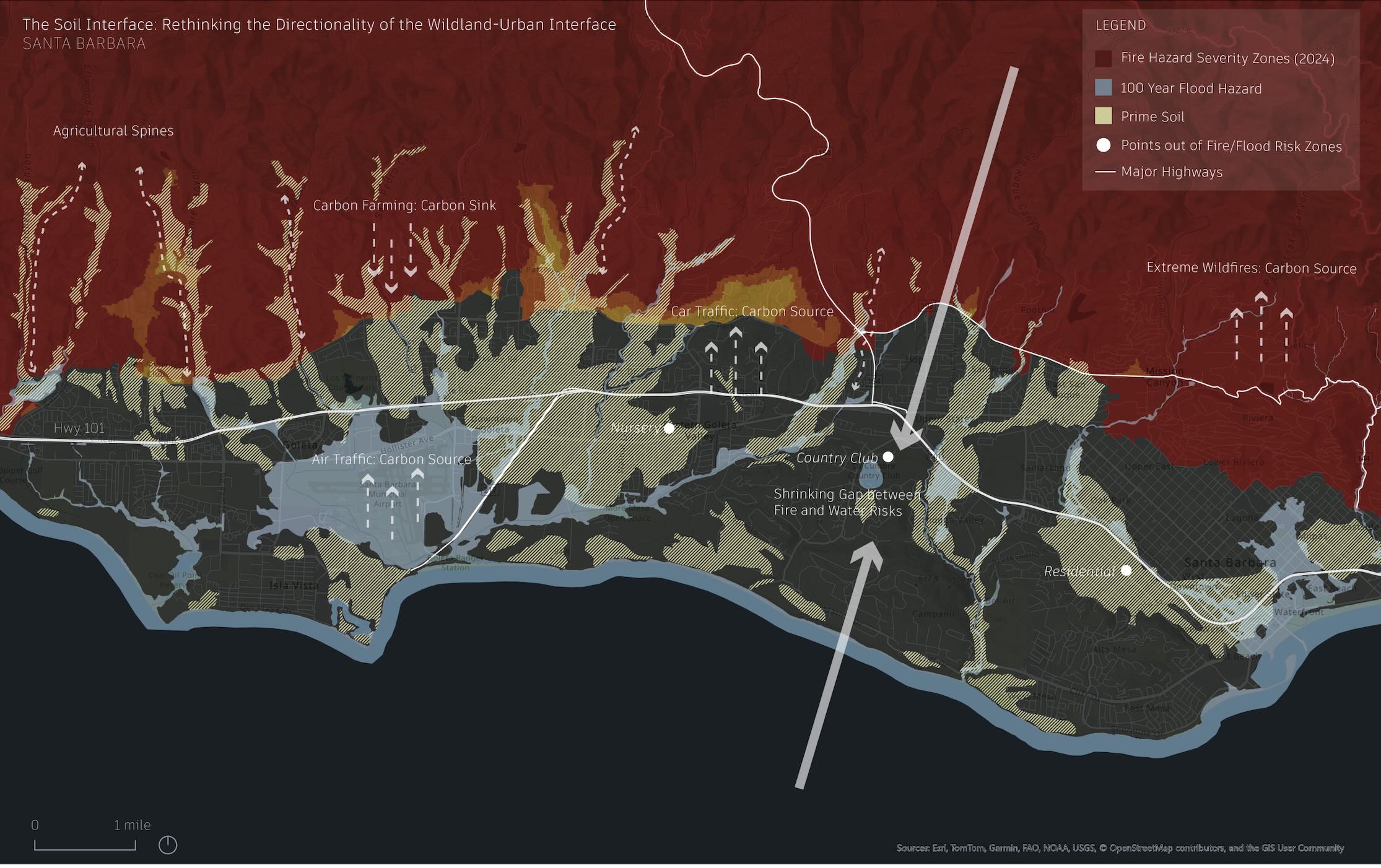

Davol took a different approach, studying soil composition to think about post-fire resiliency for humans and non-humans. In a mega-fire, she explained, the soil’s composition changes, often leaving it impermeable to rainfall. Later, instead of sinking into the soil, rain slides over the slick surface and causes floods and mudslides, further threatening the ecosystem and people’s homes and communities.

“The health of the earth and soil, and its ability to recharge and become permeable again,” she explained, “is really important for the long-term success of these landscapes.”

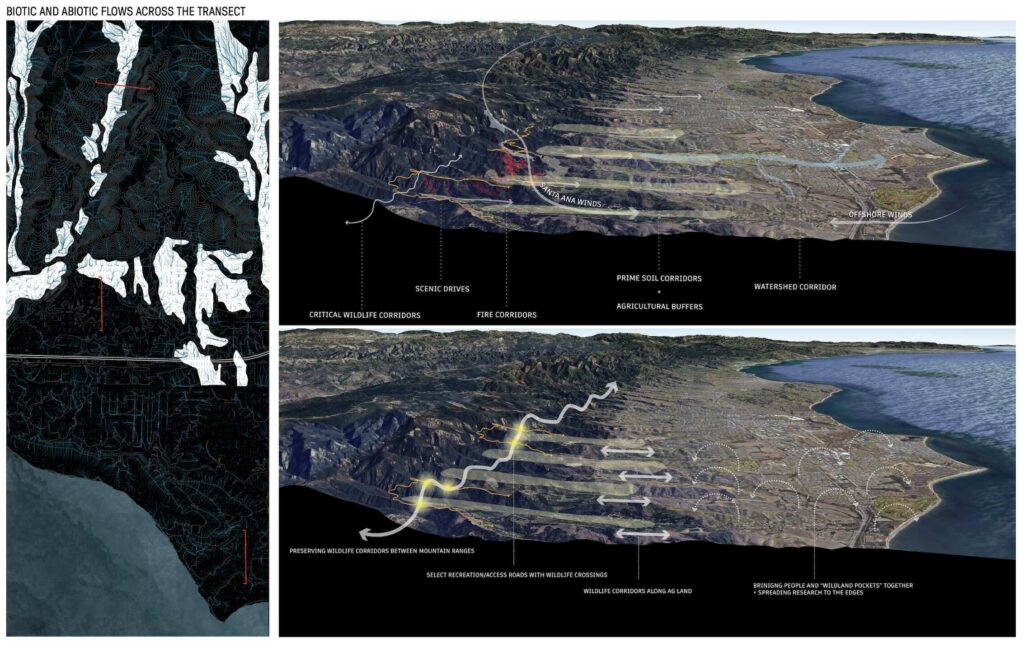

Davol mapped the soil and created corridors both to prevent fire and rehabilitate the earth, for example, with chapparal plantings. The corridors also give species in the region, such as the mountain lion, safe access across human infrastructure in the WUI. “I thought about this region as a “patchwork of green spaces that could be connected for people and wildlife.” As we “expand into the wildlands, we’re often bisecting and covering up and burying natural systems like rivers.” Her project addresses biodiversity loss and interactions between humans and nonhumans.

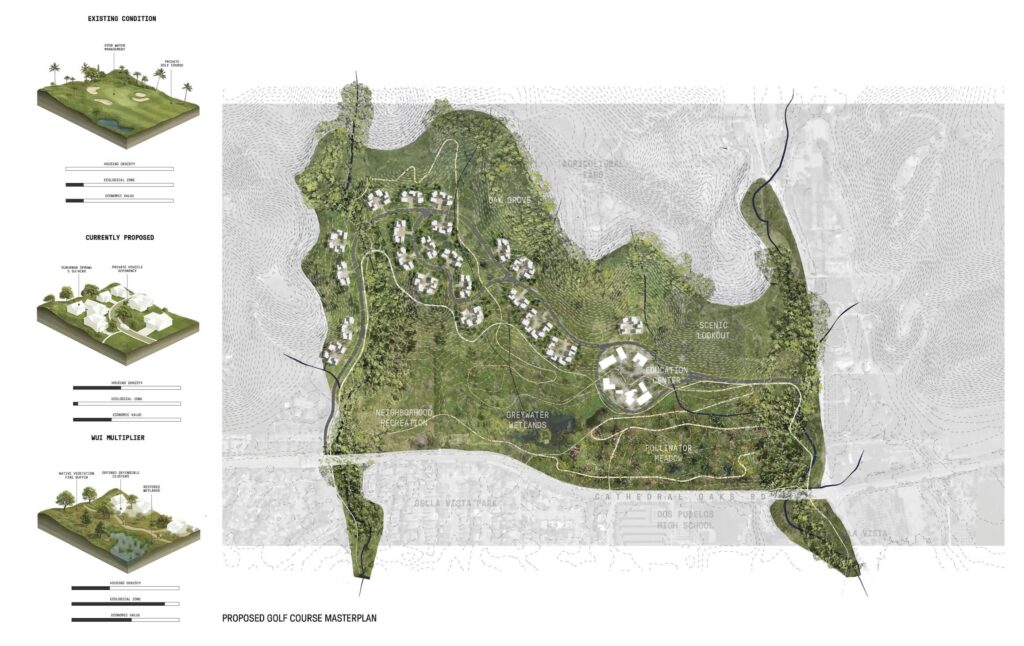

Finally, Enrique Lozano framed the WUI “not as a liability, but as a multiplier—a design tool that catalyzes infill development while preserving critical open space.” Instead of looking at the WUI as a “zone of vulnerability,” he saw it as an opportunity, using Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) from a nearby golf course to a 327 acre plot called Giorgi Farm. In the process, his proposal would increase affordable housing and restore resident access to Ygnacia Creek while also “enhancing biodiversity, using landscape as a fire buffer, promoting the wildfire corridor, and minimizing greenfield development.”

He started by mapping the residents who are most vulnerable to fire risk, and found that it’s the people “pushed out of the urban core, to the peripheries.” In addition, he found that many of the Housing Element updates in the city, which mark new housing units, fell within the WUI. Applying lessons he learned in the MAUD program and a recent Architecture and Real Estate course collaborative, he looked at the site from different scales, studying the territory at large, and using TDR’s to build affordable housing within the city while also increasing biodiversity and usable green spaces.

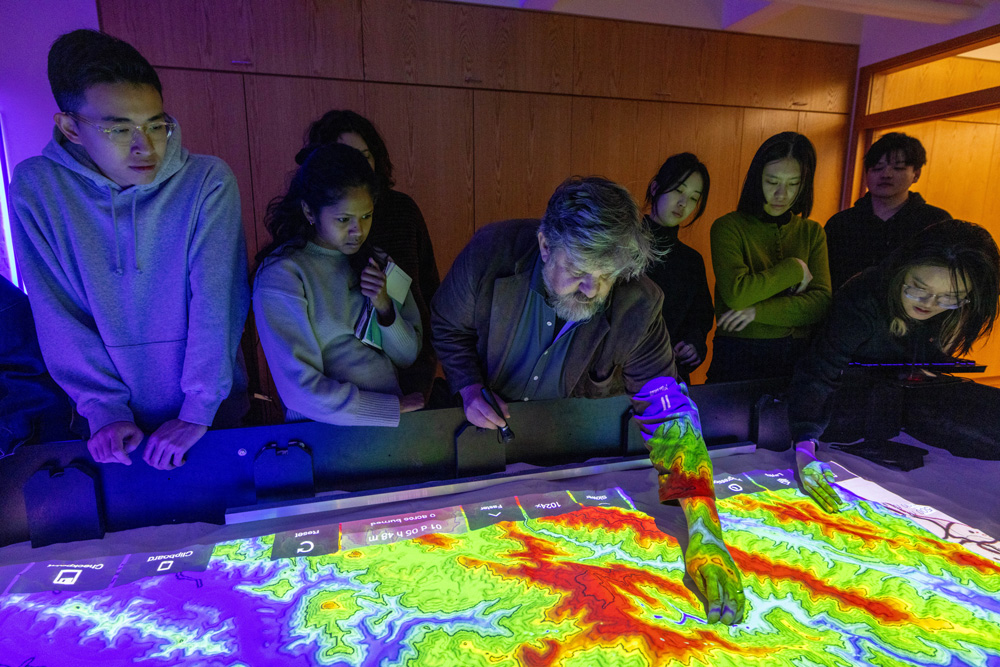

The complexity of wildfire prevention and remediation that Soraire, Davol, and Lozano address in their projects is why Susskind believes it’s so critical to establish bridges between firms like SWA and academic programs like the GSD. SWA has a long legacy of GSD collaborations, beginning with its founding in the 1950s by GSD professor Hideo Sasaki and his student, Pete Walker (MLA ’57), both of whom went on to prodigious careers. Today, Susskind regularly guest lectures at the GSD in the “Climate by Design” course, and the SWA summer cohorts often include GSD students. For example, in 2022, Slide Kelly (MLA & MDes ’24) worked on fire remediation with Susskind at SWA, and now serves as a design critic in landscape architecture at the GSD.

The GSD has long served as a site of experimentation where designers can explore issues around wildfire management and remediation, with increasing attention in recent years as climate change causes more frequent megafires. In recent years, three professors at the GSD taught classes on wildfires, and this fall, two option studios focus on fires: a new iteration of Silvia Benedito’s option studio, “Canary in the Mine,” co-taught with Kelly, takes students to the Jack Dangermond Nature Preserve in Santa Barbara County as part of their study of the aftermath of the January Los Angeles wildfires. James Lord and Roderick Wylie’s studio “Fireworks,” focuses on the Napa Valley in California, using the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art to inspire thinking around how art and landscape might, together, create a “speculative vision for the future hand in hand with design.”

These courses, along with the work that GSD students undertook in partnership with SWA this summer, mark significant opportunities for designers to intervene in the climate crisis, alleviating its impacts for humans and nonhumans alike. SWA encouraged students in the summer program to first consider “ecological systems before development,” explained Lozano. He thought first about restorative landscapes and fire buffers, and how to maximize affordable housing and resident mobility and open space, in two sites across the city.

“I wanted to show that, even though the urban core is very dense and active, and then, moving outward, there’s suburbia and then the woodlands—all of these seemingly disparate things are interdependent.” Fire mitigation requires looking at the city and suburbs as a unified system.

[i]

Katherine M. Wilkin, David Benterou, Amanda M. Stasiewicz, “High fire hazard Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) residences in California lack voluntary and mandated wildfire risk mitigation compliance in Home Ignition Zones,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Volume 124, 2025, 105435, ISSN 2212-4209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105435

.