When Leyla Uysal (MDes ’24, MLA ’27) arrived at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), she was already navigating an extraordinary path. An urban planner, entrepreneur, and mother, she had long worked to uplift Kurdish communities in her native Türkiye. Yet it was at Harvard that her journey deepened—becoming, as she puts it, “a dialogue with nature, design, and the world itself.” Through the Master of Design (MDes) and now the Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) programs, Uysal has found the GSD to be a catalyst for reimagining how creativity, culture, and ecology can intertwine to shape more compassionate and sustainable futures.

“Since my childhood, I’ve lived in close conversation with nature,” Uysal says, reflecting on her Indigenous Mesopotamian upbringing in a war-scarred area of rural Türkiye. Her Kurdish community—long oppressed by mainstream society—remained largely untouched by modernization, preserving a way of life rooted in intimacy with the land. What might have been deprivation became, in hindsight, a kind of inheritance. “Not being introduced to modernization, globalization, and industrialization has a positive impact on our bond with nature,” she explains. “We see everything as valuable and precious, and we live with much less waste. This is the blessing of not being fully modernized.”

This blessing, however, came at a cost. Education was not a birthright in Uysal’s community; it was something to be won. As a girl, she had to persuade her parents to allow her to attend school, defying customs that deemed education improper for daughters. “This was the curse of not living in a modernized setting,” she recalls. “My going to school was seen as dishonoring my culture.” Within her tribe of nearly six thousand people, Uysal became the first woman to graduate from high school—and the first person ever to attend college. Today, she notes with pride, many of her younger female relatives have followed in her path.

In time, Uysal left her family homestead for Istanbul, where she enrolled at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University. There she earned a bachelor’s degree in urban and regional planning while also studying ecology and ecosystem restoration—a synthesis that would become central to her later work. In 2012, she moved to Boston with two goals: to learn English and, inspired by Charles Waldheim’s theories of landscape urbanism, to explore opportunities for study at the GSD. Marriage and motherhood followed, and for a few years her energy turned inward, toward family and the fragile equilibrium of building a new life abroad. But the memory of her own struggles lingered. “I wanted to help others who were facing the same challenges I did,” she says.

Photo: Brian McWilliams.

That impulse gave rise to Bajer Watches , a social enterprise founded, in her words, “to empower women and children, to provide them opportunities to have a better life.” Through Bajer, which produces high-end timepieces, Uysal partners with two Turkish NGOs that create educational and employment opportunities for rural Kurdish women and children. Each watch, crafted by hand, carries a piece of that story: the leather bands are inscribed with motifs drawn from Kurdish rugs—ancient symbols of clarity, resistance, and protection once woven by women as a means of communication when traditions required their silence. “The brand brings that story to the front line,” Uysal says. “Through design and craft, we tell the world that we exist.”

Bajer soon drew attention from the press , its blend of activism and aesthetics striking a resonant chord. Yet even as her company grew, Uysal felt another calling stirring. The planner in her—the thinker who saw systems, cities, and landscapes as interconnected—was restless. “I thought, I need to go back to school,” she recalls, “and use my skills for the next generations.”

In 2022, Uysal returned to academia, enrolling in the MDes program at the Harvard GSD. It marked, as she puts it, “a beautiful new chapter in my life.” She had always felt close to nature, but the MDes program gave that intuition an intellectual framework. As a student in the Ecologies domain, she immersed herself in the science of climate systems, exploring how data, policy, and design intersect. “I took many science, data, policy, and technology classes in the context of climate change,” she says. “My perspective became more grounded, and now everything I do is rooted in it.”

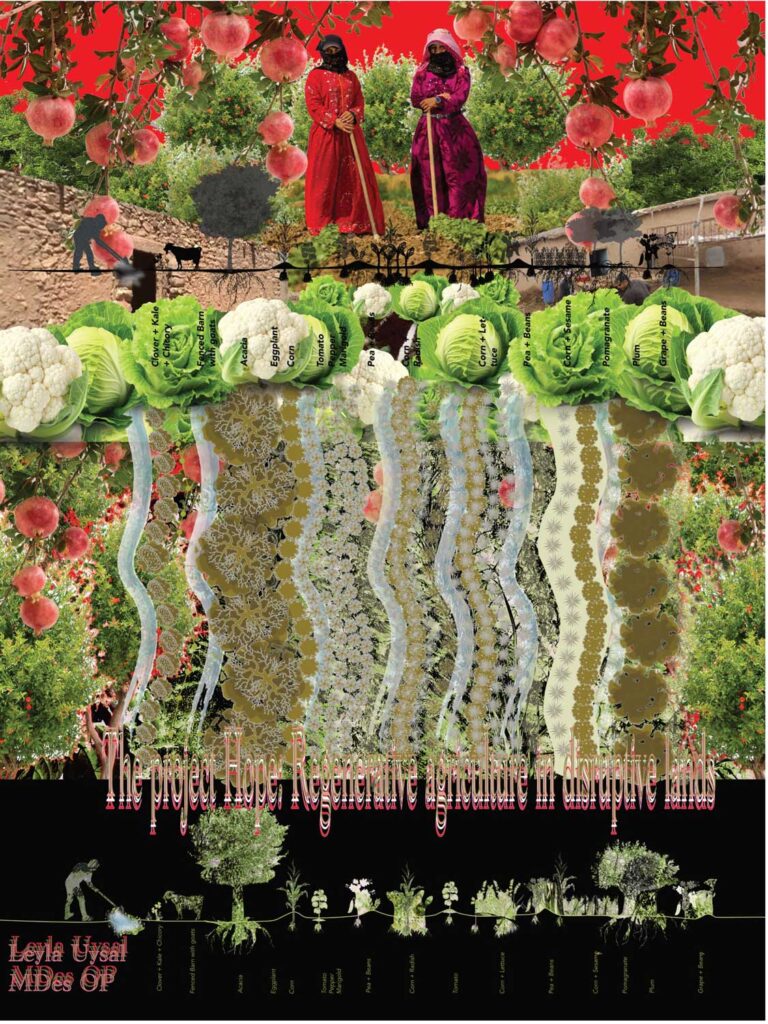

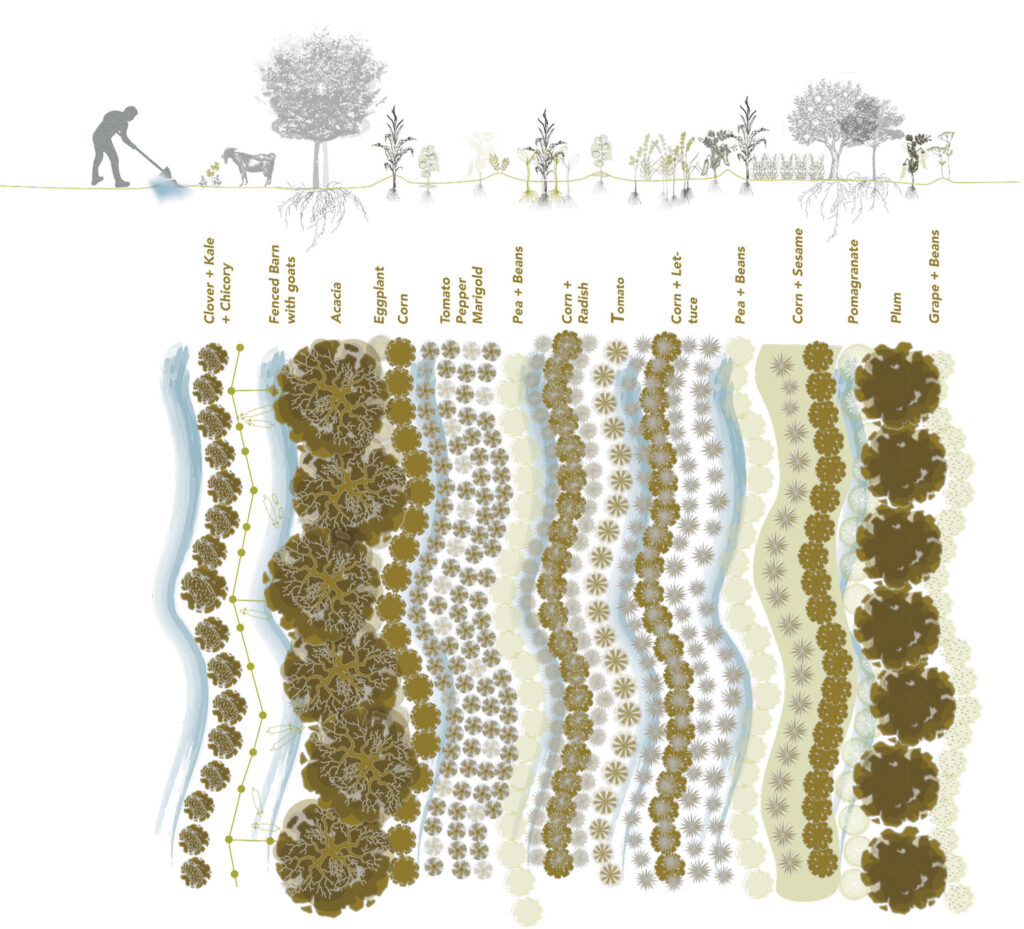

Her studies coalesced in “Project of Hope: Re-Imagining Indigenous Lands; Recovering through Memory,” supported by the Penny White Project Fund. “Project Hope” addresses the landmines scattered along Türkiye’s Syrian, Iraqi, and Iranian borders—about two million buried among ancient olive and pistachio fields—that have scarred both the land and its people. Rooted in a desire to restore memory and livelihood, the project uses landscape and permaculture design as tools to help Kurds reconnect with their sustainable farming traditions and reclaim their way of life. The work blended design, ecology, and cultural memory, proposing ways Indigenous landscapes might be repossessed—not only physically, but emotionally and symbolically.

After completing the MDes in 2024, Uysal’s curiosity only deepened. That summer, she began a PhD in environmental planning and policy program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the guidance of professors Janelle Knox-Hayes and Lawrence Susskind . Her research, ambitious in scope, examines the role of human ego in design and planning, exploring how humility and reciprocity might reshape zoning, development, and our relationship to land. “It’s about rethinking how we plan on this planet,” she says—a question that links the human scale of design to the vastness of the Earth itself.

The complexity of that inquiry soon drew her back to landscape itself. In the fall of 2025, Uysal enrolled in the MLA program at the GSD, supported by a full scholarship from the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. She describes the MLA as a foundation for her doctoral research—a way to integrate lived experience with ecological design. “It allows me to build a more inclusive, Earth-oriented, future-oriented approach,” she says, “to inspire planners, architects, and designers to rethink their work.”

This year, she added yet another layer to her work: teaching. At MIT, she is a teaching assistant for a course on quantitative and qualitative research methodologies—a role she approaches not as an authority, but as a participant in an ongoing exchange. “I’m still learning,” she says. “I’m learning from my students already.”

In some ways, Uysal’s work has always been a return—a long arc from southeastern Türkiye to the classrooms of Cambridge, from handmade rugs to digital mapping, from silence to speech. What began as a fight for an education has evolved into a philosophy of design that treats the planet as a living archive of memory and meaning. It is a perspective shaped as much by experience as by scholarship: the child who watched the seasons shift over an ancient landscape has become the scholar urging designers and planners to move with, not against, the rhythms of our planet.

Uysal’s story is less about success than about continuity—the enduring thread between land and learning, between the resilience of her Kurdish ancestors and the generative curiosity that defines her work today. “Every step,” she says, “is another way of listening—to people, to place, and to the Earth itself.”