When Brazilian designer Roberto Burle Marx created the tropical Cascade Garden within a 2,100-square-foot glasshouse at Longwood Gardens outside of Philadelphia, a local newspaper said it was “like building a ship inside a bottle.” With more than 150 species of bromeliads—plants native to the Brazilian rainforest that hold water in the center of their cup-like leaves—as well as waterfalls and shimmering pools precisely designed to feel like the Amazon’s, the garden has allowed visitors the experience of the rainforest’s biodiversity, warmth, and wonder since it opened in 1993.

Longwood Gardens is a collection of historic gardens and glasshouses in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. Its mission is to share the beauty of gardens while conserving and sustaining a vast array of plants, including threatened species, in its extensive conservatory complex. The Cascade Garden is integral to Longwood’s mission, and after 30 years, it was in need of updates and renovation. When they began planning renovations of their glasshouses, Graduate School of Design (GSD) professor of landscape architecture Anita Berrizbeitia partnered with landscape design firm Reed Hilderbrand, co-founded by Gary R. Hilderbrand, chair of the landscape architecture program at the GSD, to relocate the Cascade Garden using high-tech tools, meticulously preserving Burle Marx’s only existing project in North America. Weiss/Manfredi served as the architects of the Cascade Garden glasshouse. Their design for its exterior complements and is part of Longwood’s new West Conservatory project and the west conservatory courtyard. Berrizbeitia notes that garden restoration typically occurs in situ; thus, this is a rare example of dismantling, storing, constructing a new dedicated conservatory, and reconstructing the garden in its new location.

Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994), who was also a painter, musician, ceramicist, and jewelry designer, was clear that his tropical gardens were not intended to replicate the rainforest but to provide the experience of being within it. Walking into the Cascade Garden, the first thing visitors notice is the sound of rushing, gurgling waterfalls, the light cascading through the high glass ceilings and walls, and the plenitude of rich green, yellow, and red tropical plants.

“The Cascade Garden is an intensification of the experience of the rainforest,” Eric Kramer, principal at Reed Hilderbrand , explained. “Within a very small footprint, you are immersed in this world. It’s evocative of the experience of the rainforest, from the textures down to the fragrances.”

Kramer and his colleagues at Reed Hilderbrand, principal Kristin Frederickson and co-founder Doug Reed, partnered with Berrizbeitia, who wrote a white paper detailing the merits of the Cascade Garden’s historic and cultural value. In the era of climate change, she explained, historically significant gardens like this one are increasingly vulnerable. Preserving these gardens creates the opportunity for what she describes as designed continuity—an unbroken link between our past, present, and future. She recently curated a symposium at Longwood Gardens on the topic, with the Reed Hilderbrand team as featured speakers.

Burle Marx is world-renowned for his modernist tropical landscape designs that celebrate Brazil’s biodiversity by incorporating a wide range of species within fascinating layouts. Some of his most iconic designs include the Copacabana Beach promenade in Rio de Janeiro with its black and white waving path, Casa Cavanelas in Petrópolis, Brazil, with the checkerboard lawn of two different grass species, and the tall palm trees that reflect in the lakes at Parque del Este in Caracas, Venezuela. The child of European parents, he was raised in São Paolo, and became enamored with the vast range of plant species around him. He’s known as one of the first to advocate for preserving the Amazon in the face of rampant deforestation that continues today. He delighted in collecting rocks and cultivating plants he found in the Amazon near his home in São Paolo. Remarkably, more than 50 plant species have been named after him.

His design for the Cascade Garden at Longwood Gardens was commissioned in 1989 and completed in 1993. Conrad Hamerman, a Philadelphia-based landscape architect and long-time collaborator, served as what we would call today Landscape Architect of Record. In addition to hundreds of plants, the Cascade garden has sixteen waterfalls, four pools, and a fog-emitting system that fills the space with mist and maintains the humidity at a constant 70 percent. As is typical of Burle Marx’s work, rocks—primarily Pennsylvania mica, for its high silica content that reflects the sunlight, Colorado rose quartz, rounded cream river stones and pebbles, and granite—have an important role in the experience of the garden, augmenting the experience of light, color, and texture as they interact visually and materially with the plants.

“The garden is remarkable,” explained Berrizbeitia, “because of the interdependence of all its elements. The assemblages of plants, rocks, and water form a kind of DNA for the garden —a composition that cannot be reduced or separated. Burle Marx saw these relationships as inseparable in the natural world.”

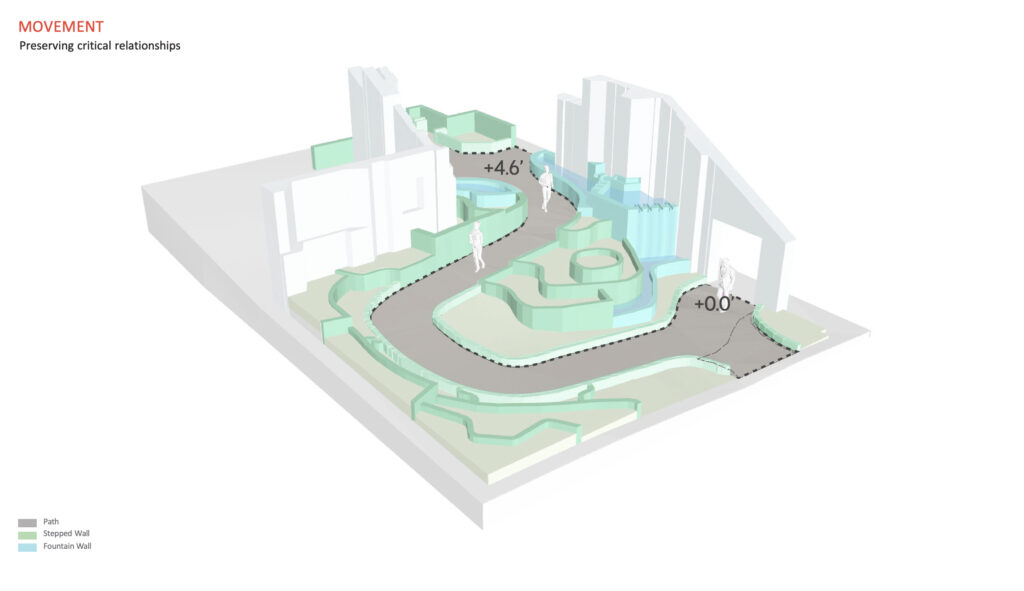

The challenge of moving the garden to a new site required not only documenting the location of each element so that it could be replaced in the new space, but also reconfiguring the garden in a glasshouse with necessary updates, such as higher ceilings, and the loss of 18 inches in grade change to make the interior accessible, better building technology, and a new misting system to maintain consistent humidity and temperatures required by tropical plants. The team turned to Longwood’s archives for the original layout and descriptions of the gardens, as well as the expertise of Longwood staff members who were part of the process with Burle Marx in the 1990s.

“The original planting plan,” said Reed, “was very clearly documented. And this sinuous path that is the primary focus of the experience had to be lowered to be less than 5 percent. That had ramifications on all of the components of the composition.”

The assiduously arranged terraces that Burle Marx designed at different heights—planting beds, waterfalls, wall cladding for plantings—all had to shift in the new glasshouse.

“Imagine,” said Kramer, referencing the ship in a bottle analogy, “that there’s now another bottle. It’s taller, and every element has to be very carefully calibrated. We undertook a process of studying it in every way it could be studied to best adapt it to the new space.”

The team took 3D scans of the garden before deconstruction, after the plants were taken out, and after the rocks were removed. They catalogued every bromeliad and aroid—flowering tropical plants—along with a myriad of other tropical plants, and each rock that Burle Marx carefully selected and placed.

An entirely new conservatory, designed by architects Weiss/Manfredi and sited at the heart of a recently opened set of gardens and glass houses, also by Weiss/Manfredi and Reed Hilderbrand, collectively known as Longwood Reimagined, now houses the reconstructed Cascade Garden. This high-performance enclosure finally gives the plants, which were becoming cramped under the old roof, new space to rise and grow, preserving Burle Marx’s vision of the rich, thriving tropical glasshouse. To recreate the original condition of elevation change that necessitated the sloping path so central to the experience of the Cascade Garden, Reed Hilderbrand also designed a transitional courtyard that people enter and slowly rise along an arcing pathway before they encounter the Cascade Garden.

“When you see a Burle Marx garden,” Berrizbeitia explained in a Longwood Gardens interview, “it fills your senses and your mind and stimulates your thinking about the environment, about life, about beauty.”

Today, people will continue to celebrate and enjoy what the team calls Burle Marx’s “jewel box” design, drawing attention not only to an important artistic and cultural space, but also transporting visitors to a rainforest desperately in need of the attention and advocacy that Burle Marx devoted to it during his lifetime.

Further Reading

A. R. Sá Carneiro, “Roberto Burle Marx (1909–94): Defining Modernism in Latin American Landscape Architecture,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 39, no. 3 (2019): 255–270.

K. Chubbuck, “Restoring the Cascade Garden of Roberto Burle Marx,” Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture, no. 67 (2025): 117–133.

M. Engler, “Symphony of Color: Tropical Saturation, Roberto Burle Marx (1909–94),” in Landscape Design in Color, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 2023), 167–193.