Redlining, Green Books, Gray Towns, High Yellow

Architect and artist Amanda Williams is best known for her bold public art project, Color(ed) Theory , produced for the 2015 architecture biennial in her native Chicago. Williams and a team of volunteers painted seven houses that were slated for demolition in the city’s predominantly Black Englewood neighborhood. Each building was coated in one color chosen from a palette Williams developed of culturally resonant hues for the surrounding community: Pink Oil Moisturizer, Ultrasheen, Harold’s Chicken Shack, Flamin’ Red Hots, Currency Exchange, Safe Passage, Crown Royal Bag. The vibrant paint conferred new life and meaning to each house, even as the dilapidated structure remained underneath.

A graduate of Cornell’s “extremely theoretical and conceptual” architecture program, Williams practiced for several years before yielding to a lifelong desire to pursue visual art full-time. After experimenting with abstract art, she eventually made her way to the intersection of art and architecture with projects like Color(ed) Theory that explore color and race and their relationship to space and value. Here, in lieu of her Open House Lecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design on April 2, 2020 that was cancelled due to the Covid-19 outbreak, Williams takes a moment to reflect on her work, purpose, and path, each of which has straddled multiple divides.

What drew you to architecture?

I grew up on the South Side of Chicago; the city is historically very segregated and continues to be. Before I had language for what was going on, I understood that there were inequities in space as we would move daily from Auburn Gresham—a predominantly Black and working/lower class neighborhood at the time—to Hyde Park, where I went to a private school. Seeing that shift piqued my interest about why and what was possible. I knew something wasn’t quite right.

At the same time, I loved art, drawing, color. There was a love of making things, of imagining people and how they would interact. I would draw houses or structures as a way to narrate stories. As I progressed, architecture seemed like the vehicle for exploring both. And when I told my parents I wanted to be an artist, my mother said, “Artists who can make a living are called architects.”

What prompted your move away from architecture in a strict sense of the discipline into visual art?

There was a long moment where my love of theory and the conceptual, and of thinking about architecture speculatively felt like a luxury I didn’t have because there was a need to actually change things. There was a bit of guilt that I could make these beautiful things and have these conversations with classmates and colleagues that I knew would be completely foreign to the environment that I had grown up in. So I practiced for about six and a half years in San Francisco during the height of the dot-com boom. We did interesting industrial projects, schools, and other civic buildings in addition to large-scale master plans for corporations. But I asked myself: Is this what you’re supposed to be doing? That transition into art full-time was that ideal moment when you could go from something you love to something you love more. Also, I really wanted to come back to Chicago and reinterrogate those early thoughts about my relationship to my creative self in the city that I love.

You’ve said that color, race, space, and value are the four things you’re constantly preoccupied with in your work. Are there patterns to how these four things interplay?

Yes. I would say that recently the idea that I can always lead with a color—and that it will have a spatial and racialized spatial corollary—is really strong. I didn’t see that early on. Color(ed) Theory led me to that: redlining, green books, gray towns, high yellow. Now I can see a whole kind of color palette that’s synchronous with color theory.

Is your exploration of color as a medium a way to get around gridlocked discussions about race? Or is it another way into those conversations?

My interest in the color gray is potentially a way to explode the kind of dead ends that we tend to fall into [around race], especially in Chicago. But the idea of race as just Black and white, for example, completely ignores the Asian community, Latinos.

When I was an artist-in-residence at Smith, I took much of the summer to think about this. What came to the fore is this idea that black and white can be combined into gray, but I also thought about other ways that you can get to gray. Another way is this tertiary—or what they call chroma—gray, where you make three colors turn into gray. That seems very powerful also as a metaphor for complicating the ways we tend to want to talk about race: if gray is not black and white but actually at least three things, then it not only expands how we have to position it, it also opens the door for trans and immigrant and others. You won’t end at the same place because now you’ve introduced a new element. People won’t be able to do what they usually do in discussions about race—ignore it and reduce the conversation. And it can help bring about potential strategies for getting out of this never-ending system that exists.

You bring art and architecture together to talk about larger social and economic and political issues. How do they serve one another?

In my mind, the art is leading. But I would say that in most people’s minds—both the everyday person and also those in the contemporary art and architectural worlds—the architecture is leading. There tends to be much more interest in the spatial implications of my work or the fact that this is a very different way of talking about space than people are accustomed to. And the artistic realm is not used to architecture being a medium as opposed to a functional thing. (I’m being very general and broad.)

Personally, I find agency in the art; there doesn’t always have to be a rationale. There’s room to think through it, to not have a conclusive answer, whatever the final product. Whereas there is an expectation that traditional architecture writ large actually needs to function: it has to stand up. People have to be able occupy it. There are rules about how it needs to operate.

There is a very distinct kind of discourse around contemporary architecture and art. They have their overlaps and there are people who have straddled those before me. But there’s not a synergy in the way one might imagine. So I’m always leading with the question, and the question is always spiraling around those four elements. I’m not thinking ahead of time what that matrix is, but it always seems to end up with those. And then if there were some kind of spectrum, you could think about whether one would initially label the final work art or architecture.

Amanda Williams was invited to lecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design on April 2, 2020. Due to the Covid-19 outbreak, public programs at the GSD were cancelled, including Williams’s Open House Lecture.

Excerpt: Urban Spaces and the Mattering of Black Lives, by Darnell L. Moore

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Just City Lab published The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city. These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

Urban Spaces and the Mattering of Black Lives

By Darnell L. Moore

It was close to midnight. A youngish, jovial-looking white woman with russet colored hair ran by me with ostensive ease. She donned earphones and dark, body-fitting jogging attire. I was walking home from the A train stop and along Lewis Avenue, which is a moderately busy thoroughfare that runs through the BedfordStuyvesant neighborhood in central Brooklyn, where I live. Lewis runs parallel to Marcus Garvey. Black. Two avenues to the right is Malcolm X Boulevard. It’s Black. Fulton Street. Atlantic Avenue. The B15 bus. Bedford Avenue. Marcy Projects. Brownstoners. The C train. Working class renters. Peaches Restaurant. June Jordan. Livery taxis. Restoration Plaza. Jay-Z. Bed-Stuy is quite black. I am, too. Encountering the strange sight of a white woman running without care on a street in a section of our borough once considered an unredeemable “hood” terrified me. She ran past the new eateries and grocery shops that sell organic and specialty foods. Within a span of a few blocks, residents and visitors now have their choice of premium Mexican eats, brick oven pizza or freshly baked scones with artisanal coffee. Citi Bike racks and skateboard-riding hipsters adorn the now buzzing thoroughfare. To many, our part of Bed-Stuy may appear safer, cleaner, and whiter. And yet, I was still terrified. It was midnight. Black boys and men have been killed throughout the history of the U.S. for being less close to and observant of white women’s bodies as I was that late evening. Shortly after I passed by the white woman jogger, my close friend, Marcus, who lives within walking distance from me—closer to a densely populated public housing development—lamented lingering tremors of gentrification. Citing the presumed changes in racial demographics, renovated housing options and increased business development efforts, Marcus hinted at the frustration of black communities undergoing rapid and contested transformation. He came upon a flier that was fastened to a tree. According to Marcus, the New York Police Department precinct near his building created a “wanted” sign that was posted not too far from where he lived. The “wanted” were a few black men who allegedly robbed a neighbor. The neighbor was white. Never before, in the several years Marcus had lived in Bed-Stuy, had he seen anything similar. There were no signs made after black teens were shot or robbed. There were no cries for the “wanted” after black women and girls were sexually assaulted or followed home by a predator. There was no indication of concern for black people besides the ever-present anxiety black bodies seem to cause both to the state and to white people when they dwell en masse in the hood. A cursory review of NYPD’s data on the disproportionate and deleterious impact of stop, question and frisk procedures and broken windows policing on black communities is but one example. Marcus’s critique resonated because it illuminated the ways the state and its citizenry afford value to white lives. Hence, the reason for selecting the vignettes I’ve opened with here. In both scenes, white bodies signify worth and, therefore, are always centered in our collective imagination. They are esteemed commodities, especially in black spaces—that is, neighborhoods and other publics mostly inhabited and culturally shaped by a majority black populace. Thus, any dreamed and invented “just city” that is structured by a set of race ideologies that do not factor in the hyper-mattering of white lives and the perceived worthlessness of black and brown lives is not “just” at all. That is why catch phrases such as “community development” or “urban planning and design” can be counterproductive if, in fact, one’s praxis is not guided by a commitment to a type of transformative work grounded in the belief that black lives actually matter. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org…Design as Protest: How can designers stand for, fight for, and build an anti-racist future?

“For nearly every injustice in the world, there is an architecture that has been planned and designed to perpetuate it,” writes the architect and activist Bryan Lee Jr. in his latest piece on CityLab. Lee spells out the ways that white America has militarized architecture and design reinforce its white supremacist ideologies and anti-Black violence in the built landscape of its cities, neighborhoods, and communities. How cities are laid out, the logics of zoning, the flow of transportation infrastructures, access to green space and the precise coordinates of urban renewal initiatives are all conceived to systemically exploit and perpetuate violence against communities of color, particularly Black Americans. Lee calls for the dismantling of the physical and political conditions that have allowed this structural and systemic racism to persist for as long as the United States is old. Now is the time, he says, to acknowledge the ways “in which our profession’s silence is assent,” so we can “stand for, fight for, and build a just future.”Mobilizing in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, Design as Protest is calling upon design professionals to dismantle the power structures and privilege that has allowed design and its contingent fields of architecture and urban planning to be utilized as a tool of oppression and violence against Black Americans for too long.

- That our cities and towns reallocate funds supporting police departments and reinvest in the critical needs of disinherited neighborhoods and communities.

- A cease to all efforts to implement defensible space and (CPTED) crime prevention through environmental design tactics.

- We cease support of the carceral state through the design of prisons, jails, and police stations.

- We cease the use of area mean income to determine “affordability” in our communities and instead root the distribution of state and federal resources in a measure that reflects the extraction of generational wealth from black communities.

- We advocate for policies and procedures that support a genuinely accessible public realm free from embedded oppression.

- We ensure communities’ self-determination through an established procedure that incorporates community voice-in-progress and community benefits agreements in action for all publicly accountable projects.

- We detangle our contractual relationships with power and capital to better serve neighborhoods and communities from a position of service and not from a place of extraction.

- We invest and secure the place-keeping of black cultural spaces.

- We proactively redesign our design training and licensing efforts to reflect the history of spatial injustice and build new measures to ground our work in service of liberating spaces.

Excerpt: Defining the Just City Beyond Black and White, by Toni L. Griffin

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Just City Lab published The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks, the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org . We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab , and editor of The Just City Essays

Defining the Just City Beyond Black and White

By Toni L. Griffin

When I think about the Just City, it’s always Black and White.

I was born in Chicago the evening before President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. Growing up on the south side of Chicago meant that on an average day, I rarely saw or interacted with a person who didn’t look like me. All of my basic needs were met on the south side of Chicago—schooling, shopping, summer jobs, recreation and entertainment. My teachers were predominately black, and my classmates were 98 percent black. This environment did not make me feel isolated, segregated or unusual—I just felt normal. Television was my only reminder that I was a “minority.” While I did not regularly see people who looked like me on TV, this didn’t stop me from deciding at the age of 14 that I wanted to be an architect—just like Mike Brady, patriarch of “The Brady Bunch.” By the time I entered college at the University of Notre Dame—and the field of architecture—my context became the exact opposite. For the first time in my life, I actually felt like a minority. And today, professionally, I remain a minority in my chosen field. I am the only African-American full-time faculty member at the City College of New York’s School of Architecture, and one of less than 300 AfricanAmerican women to be licensed in the United States.

My Just City is Black and White because I grew up in a racially segregated city.

I certainly did not realize how much of an impact Chicago’s urban form and spatial patterns would have on my perspective about cities. Nor was I aware of the profound impact that Chicago would have on my interactions with fellow urbanites and the work to which I would come to devote my career.

My work in architecture, urban design and urban planning spans several cities in the U.S., including Chicago, New York, Washington, Newark, Detroit and Memphis. All of these cities have similar racial patterns of segregation, and all have similar urban conditions, thanks to the impact of segregation on people and place. I would eventually come to know these urban conditions as the environments of social and spatial injustice. I now simply call them the conditions of urban injustice or justice. I define urban justice as the factors that contribute to our economic, human health, civic and cultural well-being, as well as the factors that contribute to the environmental and aesthetic health of the built environment. There are three conditions of urban injustice that I always seem to confront in my work in cities—conditions that began to reach the height of national awareness at the time of my birth in 1960s Chicago.

The first urban injustice conditions is concentrated poverty.

On the ground, spatial segregation has created pockets of concentrated poverty in our cities that, in turn, have created spatial and social isolation of those cities’ residents. Over multiple generations, this isolation has had a devastating impact on family structures, social networks, educational systems and access to economic opportunity.

For example, in Newark, N.J., where I served as the director of planning and community development for newly elected Mayor Cory Booker between 2007 and 2009, nearly 50 percent of all the people living in the central ward of the city lived in poverty, a condition that has persisted since a federal slum clearance boundary was drawn around the same area in 1961 and which suggests multiple generations of concentrated poverty.

The second urban injustice condition is disinvestment, crime, and the architecture of fear.

In the mid-1960s, attempts were made to revitalize the center city through programs such as Model Cities, a federal program that brought funding for redevelopment into communities with the greatest social and physical deterioration. However, the civil unrest of 1967 deepened disinvestment, and the city’s reputation for high crime and political corruption limited its ability to attract widespread capital investment for many decades. At the height of disinvestment and the federal programs designed to reverse this trend, including Model Cities and Urban Renewal, developers and institutions that felt unable to control the disinvested and crime-ridden environments around their land holdings directed architects to protect them from the adjacent urban decay via windowless recreation centers to keep children safe, elevated and enclosed skywalks from Newark Penn Station to the Gateway Center office campus that removed people from the dangerous streets, and a public community college constructed with uninviting, barrier-like building materials that created a fortress, protecting knowledge from the very public it was situated to serve. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org …

Toward a New GSD

Dear GSD community,

Four days ago, I received an ardent and thoughtful message from the GSD’s African American Student Union (AASU) and AfricaGSD, laying out 13 directions for change in response to the structural racism that has directly impacted this country’s Black population. This message coincided with communications across the faculty, also asking ourselves how we might change. I am writing you today with the beginning of a response, a response that we must all usher forward in unison. GSD students, faculty, staff, and alumni share one humanity, and the only human response to this moment is to recognize that changes need to be enacted that are real and targeted. Black Lives Matter at the GSD, and I am committed to taking the steps necessary to make sure that this becomes a lived reality for everyone at our school.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” James Baldwin wrote in 1962. This was his powerful conclusion to a call for the writers of his generation to “remake America into what we say we want it to be.”

Today, almost sixty years later, Baldwin’s call to action is ever more urgent. The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many other Black Americans, have led to a powerful wave of protests and a shared call to overturn injustices that ripple through every facet of our country and that have been borne disproportionately by the African American community.

In that same piece, Baldwin writes that “…we will never remake those cities…we will never establish human communities – until we stare our ghastly failure in the face.” We as designers, architects, urban planners and designers, and landscape architects, have contributed to that ghastly failure. We have failed by contributing to policies and designs that have concretized structural racism in our cities; compromised definitions of “public” in our public spaces, places, and buildings; and technologies that have increased, even inadvertently, environmental and economic inequities across the globe. As a school, we have also failed to meaningfully increase our numbers of Black students, faculty, and staff.

On behalf of the GSD community, I apologize that we have not served our Black community members better, historically and at present. I resolve that the school will make progress, not just with words, but with actions. I propose that we work together as a community, including our faculty, students, staff, and alumni, to enact real change, beginning with the following six measures:

- Establish for all departments and programs across the school a shared agenda, to be reviewed annually, for instilling anti-racist practices in their hiring, their visitors, their communication, and their curricula, and create a permanent page on the school’s website that includes our shared values as well as resources that advocate for racial understanding.

- Create specific programming for new student orientation and training for new faculty and staff to educate all members of our community on the specific racial context of the United States, as well as of the immediate Boston area, and how to better engage in race-related discussions and actions inside and outside the classroom. These topics will also be included within the introductory core curriculum of every program.

- Establish a GSD Gift Fund in support of anti-racism. This fund, already in the process of being created, addresses a number of demands shared in the statement from the African American Student Union (AASU) and AfricaGSD to the GSD’s administration. The school is committed to supporting initiatives aimed at combating racism, and plans to initiate this fund immediately, as a part of many actions that we will take to acknowledge that design pedagogy has a cultural obligation to address injustice and discrimination. It is our hope to engage our alumni and friends with a strong call to action that addresses the immediate needs of the GSD’s Black community, and leverages this moment in time to create systemic change.

- Identify and commit to new ways of recruiting and retaining students of color writ large, with specific efforts to recruit and retain Black students, faculty, and staff, including but not limited to expanding our numbers of Black speakers and visitors to our classes; establishing close relationships to the HBCUs; strengthening our outreach to Black communities in the Boston area; expanding Design Discovery and Design Discovery Young Adult; expanding our Community Service Fellowships; and proactively cultivating a strong network of Black professionals, alumni, and students.

- Expand faculty bias training beyond search committees to include bias issues related to grading and awards. We will also introduce a graduation prize for a student who has engaged with issues of equity in a sustained way throughout their years at the GSD, and an annual prize for a faculty member who has engaged in such issues and through their work have made a demonstrable impact.

- Review these measures annually to ensure that we are indeed remaking the school into what we want it to be.

For the GSD to stop “staring our ghastly failures in the face,” we must lead by example. We must lead by design. We must lead by conscience.

Yours kindly,

Sarah

Daniel Fernández Pascual Wins Harvard Graduate School of Design’s 2020 Wheelwright Prize

Harvard GSD is pleased to name Daniel Fernández Pascual the winner of the 2020 Wheelwright Prize , a grant to support investigative approaches to contemporary architecture, with an emphasis on globally minded research. With his winning proposal Being Shellfish: The Architecture of Intertidal Cohabitation, Fernández Pascual will examine the intertidal zone—coastal territory that is exposed to air at low tide, and covered with seawater at high tide—and its potential to advance architectural knowledge and material futures.

Observing that seaweed and shellfish have served as key sources of both nutrients and building materials for millennia, Fernández Pascual argues that their ongoing role in coastal circular economies opens new possibilities for contemporary architecture. He posits that shellfish waste shells and seaweeds may provide a basis for a new type of concrete, and could offer that and other clues to rethinking the construction sector and its impact in and on the built environment. While exploring such material futures, Fernández Pascual aims also to advance knowledge on sustaining more equitable social structures, while caring for coastal environments and cultures.

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Harvard GSD has prioritized the safety of all members of its community. Given the Wheelwright Prize’s fundamental connection between travel and research, Fernández Pascual has offered avenues for adapting his research to accommodate travel restrictions, envisioning a two-phase strategy whereby he would initiate or continue conversations with contacts at each site of interest, then travel to and visit sites during a second, later phase. He also connects the present pandemic to ongoing concerns relevant to his proposed topic, with regard to how his proposal may serve as a lens on how the human and natural worlds may cohabitate.

“We live immersed in ecologies that are eroding and changing at a rapid state, and the current global pandemic is just another sign of that environmental crisis,” Fernández Pascual observes. “As awareness about the environmental footprint of construction increases, there is an urgency to find materials that are responsive to dynamic ecosystems, to support eco-social innovation and architectural ingenuity along coastal zones, and to understand forms of cohabitation between humans and more-than-humans in order to support thriving ecosystems and societies. The Wheelwright Prize will allow me to investigate how the intertidal zone, in all of its complexity, may advance architectural knowledge in an era of climate emergency.”

“I am thrilled by the selection of Daniel Fernández Pascual as this year’s Wheelwright Prize recipient,” says Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at Harvard GSD, who served on the 2020 Wheelwright Prize jury. “By focusing on the potential of natural resources in the intertidal zone, Daniel’s proposal directly addresses one of the greatest threats our globe faces—climate change—by tackling one of architecture’s greatest contributors to that threat—concrete. Daniel has planned a dynamic research effort, reaching out to territories and societies that lie outside much of the architectural canon but that each offer variations on a theme: alternatives to using concrete as a building material. The potential for an investigation to play out so globally, and to draw in sites that offer such specific contexts, is rare, while the relevance of this topic and the care with which Daniel has organized his research agenda make me confident that this work will have a profound and widespread impact.”

Fernández Pascual was among three remarkable finalists selected from more than 170 applicants, hailing from 45 countries. The 2020 Wheelwright Prize jury commends finalists Bryony Roberts and Gustavo Utrabo for their promising research proposals and presentations.

Fernández Pascual holds a Master of Architecture from ETSA Madrid, a Master of Science in Urban Design from TU Berlin and Tongji University Shanghai, and a PhD from the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths, University of London. In 2013, Fernández Pascual co-founded Cooking Sections with Alon Schwabe. Based in London, their work explores systems that organize the world through food. Using installation, performance, mapping and video, their research-based practice operates within the overlapping boundaries of architecture, visual culture, and ecology. Since 2015 Cooking Sections have worked on multiple iterations of the long-term, site-specific CLIMAVORE project, exploring how to eat as humans change climates.

Cooking Sections was part of the exhibition at the U.S. Pavilion in the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. Their work has also been exhibited widely; upcoming solo exhibitions will take place at Tate Britain and SALT Istanbul, as well as a new commission for P.5 New Orleans Triennial. In 2019, Cooking Sections won the Future Generation Special Art Prize and were shortlisted for the Visible Award for socially-engaged practices. Cooking Sections currently lead a studio unit investigating critical questions around refuse and the metabolization of the built environment at the School of Architecture, Royal College of Art, London.

With Being Shellfish, Fernández Pascual posits that, as awareness about the environmental footprint of construction increases, especially concerning the use of concrete, the intertidal zone can offer more-responsive ways to inhabit the planet and provide regenerative materials. Seaweeds and shellfish are key sources of nutrients and have been used in construction over millennia, he observes; by looking at waste shells and seaweed material cultures in Chile, Taiwan, China, Turkey, Japan, Zanzibar, Denmark, and New Zealand, Fernández Pascual plans to extend and expand an ongoing investigation on ecosocial coastal innovations in the intertidal zone, as initiated via Cooking Sections’ CLIMAVORE project. Within these proposed case studies, Fernández Pascual plans to look at historical and contemporary innovations, such as seaweed thermal insulation and waterproof roofing, as well as the use of waste shells used as cementless binding agents, cladding, and flooring systems in different parts of the world.

Ultimately, Fernández Pascual hopes to apply the knowledge gathered via his Wheelwright research to a built project that, in turn, will incorporate and illustrate the material innovations he discovers and serve as an educational facility on coastal ecologies.

As with past Wheelwright winners, the $100,000 prize is intended to fund two years of Fernández Pascual’s research travel.

Fernández Pascual follows 2019 Wheelwright Prize winner Aleksandra Jaeschke, whose Wheelwright project UNDER WRAPS: Architecture and Culture of Greenhouses is in its travel-research phase.

Now in its eighth year as an open international competition, the Wheelwright Prize supports travel-based research initiatives proposed by extraordinary early-career architects. Previous winners have circled the globe, pursuing inquiries into a broad range of social, cultural, environmental, and technological issues. The Wheelwright Prize originated at Harvard GSD in 1935 as the Arthur C. Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship, which was established to provide a Grand Tour experience to exceptional Harvard GSD graduates at a time when international travel was rare. In 2013 Harvard GSD opened the prize to early-career architects worldwide as a competition, with the goal of encouraging new forms of prolonged, hands-on research and cross-cultural engagement. The sole eligibility requirement is that applicants must have received a degree from a professionally accredited architecture program in the previous 15 years.

The 2020 Wheelwright Prize jury consisted of 2016 Wheelwright Prize Winner Anna Puigjaner; Harvard GSD’s Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture, Sarah M. Whiting; Harvard GSD’s Chair of the Department of Architecture, Mark Lee; Harvard GSD Assistant Professor of Architecture Megan Panzano; ETH Zurich Professor of Architecture Tom Emerson; and Belgian architect Wonne Ickx.

2020 Wheelwright Prize Finalists

The Wheelwright Prize jury commends the 2020 finalists for their outstanding applications:

Bryony Roberts

Wheelwright proposal: The Architecture of Childcare: A Global Study of Experimental Models

Bryony Roberts is an architectural designer and scholar. Her practice Bryony Roberts Studio, based in New York, integrates methods from architecture, art, and preservation to address complex social conditions and urban change. The practice has been awarded the Architectural League Prize and New Practices New York from AIA New York as well as support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Graham Foundation, the MacDowell Colony, and the American Academy in Rome, where Roberts was awarded the Rome Prize for 2015-2016. In tandem with her design practice, Roberts instigates research and publication projects about designing in response to social and cultural histories. She guest-edited the recent volume Log 48: Expanding Modes of Practice, edited the book Tabula Plena: Forms of Urban Preservation published by Lars Müller Publishers, and co-guest-edited Log 31: New Ancients. She has also published her research in Harvard Design Magazine, Praxis, Future Anterior, and Architectural Record.

Roberts earned her Bachelor of Arts at Yale University and her Master of Architecture at the Princeton School of Architecture, where she was awarded the Suzanne Kolarik Underwood Thesis Prize and the Henry Adams AIA Medal. She teaches architecture and preservation at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation in New York.

With The Architecture of Childcare, Roberts proposes an analysis of experimental models of care that hybridize programs to improve conditions for children, families, and care workers: childcare plus housing, childcare plus workplace, and childcare plus landscape. Comparing projects in Scandinavia, the UK, the US, Japan, and Southeast Asia through analytical drawings and contextual research, Roberts seeks to yield a global catalogue of new typologies.

Gustavo Utrabo

Wheelwright proposal: Rethinking Nature, Assembling Matter

Born in Curitiba, Brazil, Gustavo Utrabo received a degree in architecture and urbanism from the Federal University of Paraná in Curitiba, Brazil, in 2010. In 2014, he also completed a specialization course in National History and Literature from UTFPR. Through his studio, Estúdio Gustavo Utrabo, he intends to expand the architecture field, connect people, and imagine the future through sustainable and inclusive approaches. These approaches come together in an extensive portfolio that has earned significant awards as the RIBA International Prize (2018), RIBA International Emerging Architect (2018), finalist status in Harvard GSD’s 2018 Wheelwright Prize, and a “Highly Commended” award in the Architectural Review Emerging Architecture Awards (2019), among others. Utrabo has contributed to lectures and other actions in institutions including IIT Chicago, University of Hong Kong, Future Architecture Platform at MAO museum in Ljubljana, RIBA London, and FAU-USP in São Paulo, among others. Utrabo recently served as a visiting professor in the Master of Arts program at the University of Hong Kong.

Eyeing intersections between culture, nature, and economics, especially amid ongoing climate change, Utrabo proposes an investigation into merging nature and culture through matter. With “Rethinking Nature, Assembling Matter,” he seeks an understanding of how wood, from its natural, raw status to its final use in architecture, can be used as a primordial resource to compose a cultural manifestation.

Yotam Ben Hur awarded KPF Foundation’s Paul Katz Fellowship

Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Yotam Ben Hur (MArch ’20) is one of two recipients of the Kohn Pedersen Fox Foundation’s 2020 Paul Katz Fellowship, an internationally recognized award that honors the life and work of former KPF Principal Paul Katz. The GSD’s Ian Miley (MArch ’20) was also recognized with one of two honorable mentions.

The KPF Foundation sponsors a series of annual fellowships to support emerging designers and advance international research. According to KPF, the Paul Katz Fellowship is given each year to assist international students in studying issues of global urbanism. The award is open to students enrolled in a masters of architecture program at five East Coast universities at which Katz studied or taught: Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania.

KPF focuses each annual iteration of the Paul Katz Fellowship on a different global city. This year’s fellowship is tied to Mexico City; previous cities include Tel Aviv, Sydney, London, and Tokyo. Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, KPF has announced that they will pause any travel requirements, and will distribute half of the $25,000 travel stipend as a financial award to each winner.

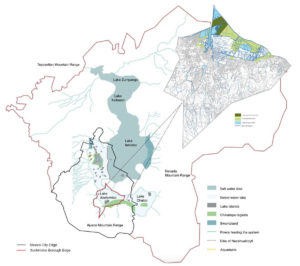

For the fellowship, Ben Hur submitted a research proposal examining the relationship between nature and architecture in peri-urban Mexico City with a concentration on the region’s informal settlements and their effect on the ecological water crisis the city is facing. Farshid Moussavi, professor in Practice of Architecture, was Ben Hur’s faculty advisor; Jacob Reidel, assistant professor in Practice of Architecture, and Eric Höweler, associate professor of Architecture, served as faculty reviewers.

“My proposal was ignited by the accumulation of different experiences and lessons I’ve gained while being at the GSD,” Ben Hur says. Reflecting on his proposal, he emphasizes the value of looking outward into the countryside rather than remaining focused on urban or familiar surroundings. He considered the complexities and challenges of designing living spaces for high-density environments characterized by informal development, as well as what he describes as “our constant battle with climate change, and our desire to find balance between the natural and the built environments.”

“Mexico City has entered a stage in which, on the one hand, there is a great need for public works, housing, and service infrastructure for the peri-urban poor, and on the other, huge pressures are being placed to conserve the surrounding environment on the verge of a climate crisis,” Ben Hur writes in his research proposal. “In this constant battle between architecture and nature, between the need to urbanize land and the desire to conserve and restore the landscape, architects and planners must intervene and redefine the relationships between the two entities, to end the loss and offer a solution of coexistence—an approach that does not separate the two realities, but rather sees the informal settlements and the natural, protected areas as components of the same ecosystem.”

Ben Hur and Miley follow a legacy of GSD students who have been honored with the Paul Katz Fellowship, including 2019 winner Miriam Alexandroff (MArch ’19) and 2018 winner Sonny Xu (MArch ’18, MLA ’18).

The KPF Foundation also organizes other fellowships, lectureships, and education-minded programs. Last year, the GSD’s Peteris Lazovskis (MArch ’20) was among three recipients of the KPF Traveling Fellowship, earning a $10,000 grant to support a summer of travel and exploration before a final year at school.

“Minneapolis Affects Us All”

Congratulations to all, especially our Class of 2020, for finishing out the academic year with the flourish of a truly memorable Commencement yesterday. While this week has been filled with mirth for so many, it has been marred by violence and injustice for others across our country, pain of various forms that directly and indirectly affects countless among us. As we celebrate our GSD community, it is equally imperative that we pause to acknowledge the events of racial violence and degradation that were permitted to take place in this week.

The death of a black man, George Floyd, in Minneapolis has resurfaced a national conversation about race in America. His murder, coupled with other racially charged occurrences this week, has reminded us that race textures the American experience. As a community of shared values, the GSD strives to recognize diverse perspectives and experiences, and to create spaces for them and their stories; this is an integral part of our mission as a design school. I asked our graduates yesterday to go out and lead the conversations that unite us as global citizens. This conversation happening right now across the country is one that needs all of our voices, and needs it now.

The GSD teaches students how to shape our world, engaging not only buildings, technologies, infrastructures, landscapes, and spaces, but also what it means for us to live together in the world. The death of Mr. Floyd and the events of this week have been tragic, with implications for every corner of our community and for each of our disciplines. It is important that while we have been forced to reframe what community looks like spatially in the face of COVID-19, we never lose sight of what community should feel like. No element or facet of your design work is too small or too isolated to impact our broader world.

As designers and as citizens of the world, I urge you to recognize and acknowledge the injustices that remain so persistent and so ingrained across our globe, and I ask you always to take the time to consider how the work we do as designers impacts how we live together.

In this moment, and as we move forward, I ask that you recognize and talk with one another about the different experiences, the different forms of pain and of understanding, that people may feel given what we’re seeing in the news and on social media. I recognize that the recent events may cause additional emotional distress and anxiety, and I urge you to be in touch with either Harvard Counseling and Mental Health Services or the Harvard Employee Assistance Program if you need assistance.

I so look forward to us all uniting again and continuing our work: educating and inspiring leaders who will create a more resilient, more beautiful, and more just world.

With respect and reflection,

Sarah

*This posting has been modified slightly from the original in response to criticism from a student who questioned the lack of reference to Mr. Floyd as black or as African American. I appreciate and acknowledge that criticism.

How can design improve disease modeling and outbreak response? A simulation tool by GSD alum Michael de St. Aubin offers answers

The global COVID-19 pandemic has placed roughly one-third of the human population on some form of lockdown. But with spring in full swing, economies in free fall, and infections on the decline in early hotspots, many are antsy to get back to work, school, and life as we once knew it. Health experts, citing disease models, warn that easing restrictions too soon could cause the virus to flare up again. The silver bullet of a coronavirus vaccine is still at least a year out, which means the burden of containing the epidemic continues to fall on the public, who must sustain distancing behaviors even as it costs us our jobs, social lives, and everyday routines. But when the worst appears to be behind us and we’re finally descending the other side of the curve, how will we convince billions of people, blinded by the light at the end of the tunnel, to keep cooperating until COVID-19 is gone for good?

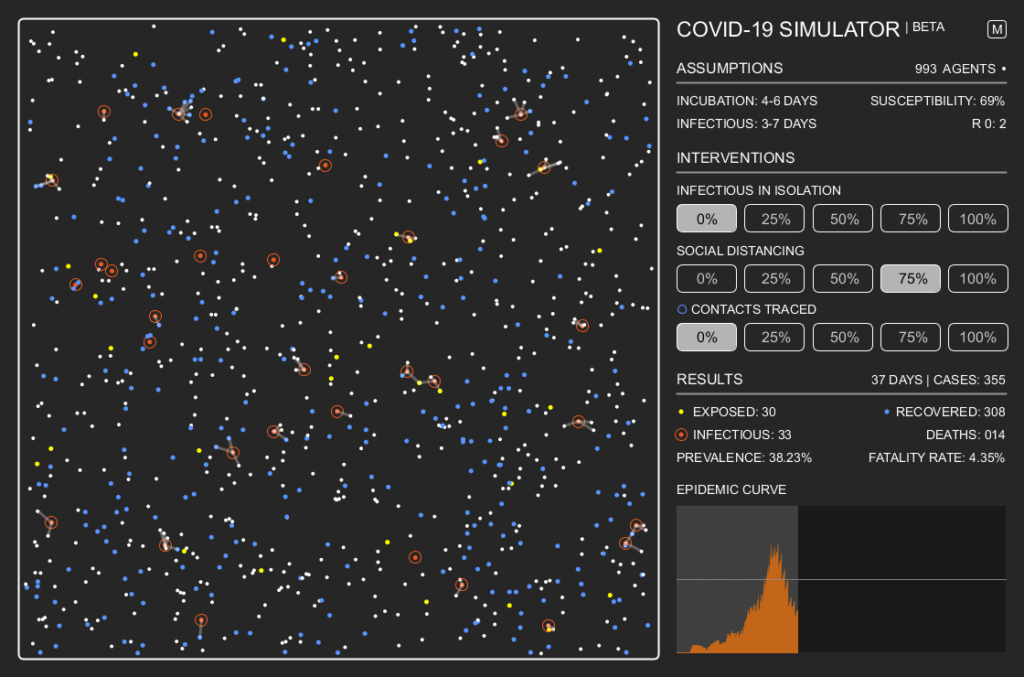

Harvard Graduate School of Design alum Michael de St. Aubin thinks better-designed disease models can have a greater impact on the public, as well as on healthcare and policy decision-makers, by helping us to see just how much our actions matter during the midst of an epidemic and after we’ve flattened the curve. Combining the sophisticated mathematical formulas of an epidemiological model with the look and feel of a computer game, his Visual Response Simulator , or ViRS, is a web-based visualization tool that’s designed with non-experts in mind. “The [visualization of inputs and outputs of] models used by health professionals or referenced by media outlets come from academic institutions—they’re set up for people with a background in epidemiology, and they’re kind of archaic,” notes de St. Aubin, an architect by training. “ViRS brings these ideas up to speed with modern interaction and visualization. It makes disease modeling more accessible to a wider audience by making it as easy as possible to understand.”

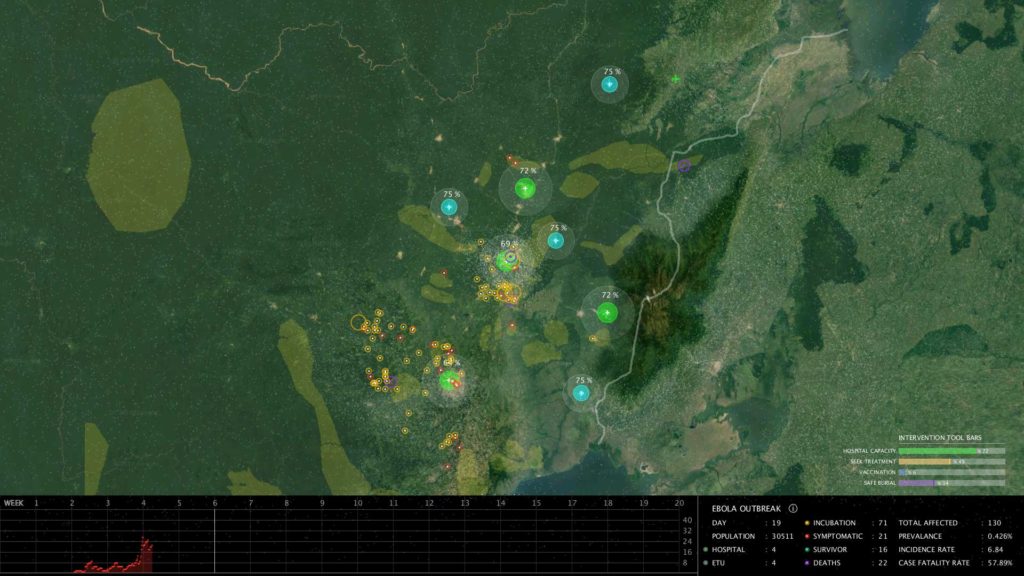

De St. Aubin plans to partner with video game designers to create ViRS’s interactive interface. The platform is specifically designed so people can test the impact of different outbreak response strategies (such as vaccination, public education, or mobile health facilities) from the moment they are implemented, and quickly see what happens when these interventions are scaled up or down. Traditional disease models, by contrast, demand any response tactics be determined at the outset, and require dozens of epidemic simulations run to their completion before returning the mean results. “I’ve built ViRS so the user can control and change their strategy mid-simulation run,” de St. Aubin points out. “It gives you the interaction to manipulate it in real time and visualizes all of those effects so it’s easy to see what’s working.”

Also unique is the integration of satellite imagery and geo-spatial data, which factors in population density, transportation networks, and existing hospital facilities in a given location. ViRS’s on-screen simulation provides a bird’s-eye view as a population of autonomous agents is ravaged by disease in accelerated time. Toolbars allow for toggling intervention variables, while counters track the total number of exposures, infections, and deaths. As the disease progresses, a now-familiar epidemic curve plots out the levels of infection over time, with spikes and dips appearing where interventions were imposed or lifted.

De St. Aubin began developing ViRS in 2017 as a graduate student in the Risk and Resilience concentration in the Masters in Design Studies program. Originally designed to model data from Ebola outbreaks in Western Africa, the simulator can be tailored to the characteristics of any disease, real or hypothetical. While in quarantine over the past several weeks, de St. Aubin adapted ViRS to create a basic interactive simulation for the current COVID-19 pandemic, using scientific research on the disease’s dynamics. “Right now, a lot of people are interested in epidemiology models and how they’re used. This particular model is for public engagement and knowledge sharing,” he says. The COVID-19 simulation lets users see for themselves how adhering to social distancing and self-isolation guidelines can dramatically flatten the curve of the outbreak, and more critically, what might happen if such restrictions are lifted in the crucial months ahead.

In this simulation, the hapless agents are rendered as dots moving around inside an empty box, bumping into and infecting one another with increasing speed as the disease permeates the population. But with one click, users can enact social distancing measures that immobilize 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent of the dots and send the infection curve plummeting. Remove the intervention tactics and infection rates resume their climb once more. “It’s a simple tool people can interact with and learn from, and it demonstrates why these non-clinical public health interventions are so important,” says de St. Aubin.

Since graduating in 2018, de St. Aubin has been working with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and continuing to refine ViRS to model response strategies for combating Ebola. (With another team at the H.H.I., he has also developed a global COVID-19 perceptions, knowledge, and behaviors survey , and a dashboard for visualizing and filtering survey data.) While ViRS is not yet validated for official use, de St. Aubin already foresees how the platform could bring value to a number of different applications.

Primarily, he envisions ViRS as a tool to get the public to learn about, support, and adhere to health guidelines. “The interaction and the visual qualities make it much easier to convince people how—if these intervention strategies are followed and to what degree—the outbreak can be contained and come to a stop,” he says. Its multiple-scenario, game-like properties, and graphic interface also make ViRS an ideal tool for epidemiology and outbreak training and education. Further, when used operationally in the field, the simulator could rapidly test response tactics and inform contingency plans, while making data easy to visualize and share for coordinating response efforts across teams.

De St. Aubin first became interested in public health and epidemiology in 2015, while working as an architect in Boston. Traveling to Ebola-stricken regions of Africa to do hospital facility assessments, he saw outbreak response in action. “There was a huge lack of designers in this profession and not a lot of design thinking, or design sensibilities,” he recalls. “I felt like I could fill a gap. I went to school thinking, ‘How can I increase my value as a designer and integrate myself into this field full-time?’”

At the GSD, de St. Aubin found the Risk and Resilience concentration a natural fit with its commitment to countering social and political issues through design. There, he took a step away from architecture, pursuing research in mapping, technology, and humanitarian response, augmented with classwork at the Harvard School of Public Health and a data visualization course at MIT. Although he was the only student in his cohort focused on infectious disease modeling, de St. Aubin predicts the growing threat of global pandemics will inspire more designers to become interested in this area. “If designers are really serious about making a difference, we can’t continue to operate in a vacuum,” he says. “We need to integrate ourselves with the fields and organizations that are doing the work directly and leading the charge, working with different UN agencies, different international organizations, and local NGOs as well.”

COVID-19 has spurred architects and designers around the world into action; they’re creating open-source files for 3-D printing respirator valves and face shields, translating the UN’s critical health messages into impactful graphics, and designing temporary coronavirus testing facilities . This unprecedented global pandemic has taught us that design can play a crucial role in better preparing us for the challenges and opportunities presented by future outbreaks, and that our individual actions and contributions can make a huge difference for the welfare of the greater good.

“Designers can get involved in so many ways, not just disease modeling, but also planning—coming up with policies and guidelines for our urban spaces to be more adaptive to these sorts of things. Rethinking how people are going to be living in the future so it’s not a total shock to our communities and our economy when everyone is forced to stay at home,” says de St. Aubin. “Our creativity and ability to forward-think is going to be really useful. There’s going to be so much need and focus on that for better resiliency in the future.”

Diane Davis on the GSD’s Risk and Resilience track

In these tough times, when dystopian fears loom large and the design professions are scrambling to find new ways of addressing the COVID-19 global crisis, it is worth reflecting on the history of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s efforts to offer a programmatic venue for students and faculty to address extreme vulnerabilities in the built environment. The recent global health pandemic may be the latest such crisis, but it is far from the first. We at the GSD have been strengthening our focus on similarly catastrophic events through the Risk and Resilience track of the Master in Design Studies program.

Over the last several years, students who joined our cohort have been addressing built environmental and design challenges related to climate change, health and environmental crises, warfare, and other “natural” or man-made disasters that disrupt systems, societies, and the lives of everyday people. We can only assume that student interest in similarly pressing matters will continue to rise, not just in response to the current pandemic, but also as all humankind faces a world where certainty, stability, and progress are no longer a given. In light of these challenges, we want to share the intellectual and programmatic journey that led to the development of the Risk and Resilience track at the GSD.

Whether conceived in terms of ‘bouncing back to normal’ after a disaster, or as a means of reestablishing system equilibrium after a shock, embracing resilience can be translated as having faith that with enough attention and adaptive effort, the future can be better.

When I came to Harvard in 2012, the Master in Design Studies program offered a variety of specializations for students, one of which was called “Anticipatory Spatial Practices.” The track already had a small cohort of students enrolled. I wondered what exactly they thought they would be doing in a program with such a title. The moniker seemed pretentious at best, and incomprehensible at worst. I also was of the opinion that everything about the planning and design professions necessarily requires or embodies some form of anticipatory spatial practice. If a program that set as its conceptual ambition a desire to engage the fundamental telos of the design disciplines in their entirety, could it be specific enough to generate something novel? I quickly learned from students that their ambitions were actually quite grounded, and that they found this track an invitation to focus on some of the most important challenges of our times.

The vast majority of our students were—and still are—interested in climate change and environmental sustainability, having understood that rapid urbanization of the built environment had spatially transformed our cities, landscapes, and the globe in ways that were undermining our collective capacities to remain healthy as a species and a planet. In that sense, the title of the track offered an opportunity to think about what could or should be different in terms of spatial practices to push back against these problems. Yet I also noted that a few of our enrolled students had come to the GSD from the world of war, so to speak, having worked in refugee camps or combat situations where both the threat and reality of violence produced its own form of crisis, ranging from forced displacement to death. These students, like the climate and environmental activists, recognized a clear need for spatial preemption of the most egregious losses and vulnerabilities associated with traumatic, violent events. The intersection of these sets of challenges drew me to the track, which I subsequently agreed to co-direct, starting in 2014.

What most captured my imagination were the parallels that thread through the various problems under study. Despite what looked like very different subjects, there seemed to be some common questions that concerned students interested both in the environmental crisis and the refugee crisis. It was not just that students focusing on these distinct topics were concerned with issues of displacement; it also appeared that common languages were emerging across the disparate problem areas. Two of the most obvious terms were “resilience” and “risk.” In recognition of a potentially unifying discourse, the program leadership agreed to shift the track’s title, and used this shift to both craft and reflect new pedagogical aims.

While students would continue to think projectively about alternative futures and how to construct them (i.e., anticipatory spatial practices), they would also be charged with transcending disciplinary and problem-area silos in the study of vulnerabilities. This pedagogy encouraged students interested in environmental crises or climate change to learn from students interested in war and vice versa, as they entered a program asking them to find parallels in these two “battlefields” of action. It also gave them an opportunity to reflect on the languages, theories, and design practices commonly deployed in each of these seemingly incongruent problem areas, and innovate new actionable framings through this cross-fertilization.

With this mandate in mind, in 2014 we formally changed the track’s title to “Risk and Resilience,” and never looked back. We have encouraged students to ask whether the concepts, practices, and assumptions about scales of agency common among those addressing one form of crisis can be applied to another. For example, if scholars addressing the climate crisis deployed approaches that echo those concerned with war, forced displacement, and other risks experienced by victims of ongoing violence, would new possibilities for action emerge? In light of COVID-19, which has been described through languages of warfare—with the virus seen as a stealth enemy that knows no territorial boundaries and that can leave a trail of damage and death in its wake—this decision now seems prescient.

Our mission statement, crafted in 2015 and posted on our web page, was the following:

The world faces unpredictable challenges at increasing intensities—natural disasters, ecological uncertainty, public health crises, extreme social inequity, rising violence—and yet counters and absorbs risk through acts of resilience. Risk & Resilience, a concentration area within the Master in Design Studies, sets out to support novelapproaches to socio–spatial planning through design. Design as a discipline provides cities, communities, and individuals with tools to effectively prepare for, cope with, and anticipate rapid change within the spatial, social and economic vulnerabilities it produces. The program prepares students to identify, articulate and propose preemptive forms of socio-spatial and territorial practice. While the program is grounded in the physical and tectonic realities of location, social and political conflicts over risk and resilience are just as likely to emerge and serve as sites of investigation (1).

As we face the global virus pandemic, our mission appears ever more important. With our skill sets as designers and planners marshalled in the service of identifying novel ways to confront this newest crisis, we can learn from some of the pedagogical challenges rippling through the track as it has evolved over the years. One is the importance of prioritizing the concept of risk, perhaps even over resilience, as we confront unknown futures that will undoubtedly present continual new threats, including those not yet anticipated.

When we launched the new track title in 2014, the notion of “resilience” was taking the policy, design, and urban planning worlds by storm. It defined the Rockefeller Foundation’s global initiative, 100 Resilient Cities, and the language of resilience appeared in a barrage of academic conferences and study centers hosted by universities and multilaterals. It also came to define new programs sponsored by technology corporations and design firms (including the joint IBM-AECOM piloting of a disaster resilience scorecard), and was even featured in the US State Department’s appropriation of resilience as a thematic rationale for international aid. The latter was built around the understanding that environmental vulnerabilities, broadly defined, are inextricably linked to problems of poverty, conflict, and violence. With the benefit of hindsight, we can now also add climate change to the list of factors that lead to migration and warfare.

The point is that when we renamed the track, the notion of resilience was being promoted as the basis for a new and expanding repertoire of tools—from novel technologies to reconfigured mapping and building products—that would guide us to a secure urban and global future. But focusing on resilience, which is frequently defined as the ability to cope and adapt so that individuals or communities survive and thrive, often meant avoiding the hard questions of power, inequality, and the ways that limited resources forced people to fend for themselves.

Whether conceived in terms of “bouncing back to normal” after a disaster, or as a means of reestablishing system equilibrium after a shock, embracing resilience can be translated as having faith that with enough attention and adaptive effort, the future can be better. But as we fall headlong into a state of irreversible environmental damage to the planet, and as some experts are suggesting that the coronavirus may be with us to stay, longstanding faith in this concept may seem a bit naive. After all, the future is still so clearly unknown, and the long-term damages that COVID-19 will produce in the health of individuals, the health of cities, and the health of economies has yet to be fully understood.

From the moment we inaugurated the new track title at the GSD, we understood that “resilience” is a tricky word, readily veering into the ideological. Some scholars have criticized this concept as offering an excuse to let citizens cope on their own while the government and the market continue to aid each other (2). Others argue that a return to normalcy is what we must avoid, because “normalcy” is often what produces crisis in the first place (3). Such an argument is frequently made in discussions of climate change and environmental crisis, which leads to deliberations about how normal it is to have built cities and societies around infrastructures and forms of resource extraction that contribute to skyrocketing carbon emissions.

From the vantage point of MDes, however, our greatest concern was that a focus on resilience might become an invitation to ignore risk, and lead us to ignore the inter-relationalities of risk that may constrain resilience. For precisely this reason, the track defines itself as engaged with concepts of both risk and resilience, and their relationships to each other (4). Our students have been encouraged to examine the trade-offs among forms and patterns of risk and resilience: not just among different residents or locations in the same city, but also in terms of immediate versus long-term gains in livability, such that coping strategies in some domains (say environment) may actually reinforce the structural problems that create risks in other domains (say inequality). To the extent that urban, social, economic, and environmental ecologies are interconnected—both locally and across territories that link cities to regions and beyond—any resilience strategy must be grounded in an appreciation of the entire landscape of a city and its properties as a system embedded in a larger ecology.

So the GSD does not aim to jettison a concern with resilience, but rather, to situate it in territorial scales while also interrogating and reconceptualizing its utility as a concept. One way to do so is to disaggregate adaptation strategies, and understand when adaptive responses to vulnerabilities or crises will establish a pathway toward a better future. Stated differently, under what conditions will adaptations—whether voluntarily undertaken by citizens, mandated by governing authorities, or crafted by planners and designers—diminish rather than increase vulnerability, and perhaps even remain effective in transforming overall vulnerabilities?

In my own work on urban violence, I have proposed that we think more carefully about positive, negative, and equilibrium resilience as three possible outcomes, with an understanding of how strategic and tactical actions may be reformulated by political, social, and economic structures to produce negative instead of positive pathways out of crisis (5). For anyone interested in the relationship between risk and resilience, or in designing new strategies to address vulnerability, the focus must be as much on the context in which adaptations are proposed as on the mechanics or design of the adaptation itself. Design thinking or design and planning action must start from an understanding of this complexity, and with the acknowledgement that any single project or policy intervention will have implications far beyond its targeted scope, both in scalar and sectoral terms.

To enable constructive action in the context of multiplying and interconnected vulnerabilities that unfold at the local and the global scale, we thus return to the idea of risk. In the MDes track, our students build, design, and plan for risk rather than just resilience. They are creating new guiding principles and paradigms in the process. In the heyday of modernism, many professional designers, architects, and planners found inspiration in dreams of order; their commitment was founded on the belief that tensions between the natural and the built and social environment could be managed if not overcome. When modernist paradigms ruled, the tendency to build better reinforced faith in the inevitability of progress, and in the belief that any new urban or built environmental challenge could be resolved if enough technology, money, and creativity were thrown at it.

Now, in the midst of a global pandemic and at a time of accelerating risks, such assumptions are the subject of interrogation. We continue to train our students to be up to the task of facing the 21st century and imagining how it should be if risk is to be contained or reduced. This requires all of us to recognize that many of the strategies associated with the modernist agenda have created insurmountable problems for us today. Some argue that the COVID-19 pandemic is a consequence of our systematic destruction of the natural world in order to acquire territories and material resources—and that by devastating animal habitats we hastened the spread of viruses between animals and humans. Others highlight the impacts of intensifying economic globalization on the flow of goods, people, and yes, viruses, that accompany capital as it moves around the world. At this point it may be too late to turn back the clock on the damages already wrought and the terrors already unleashed; but we do not have the luxury of ignoring where we could and should be heading.

This is the mandate of the Risk and Resilience track and the committed students who join this program: to embrace a mission to address some of the most fundamental risks of our times. In addition to considering new building and design techniques, they are thinking more purposefully about the form and connectivity of cities, which are conceived as sites that host intra-urban spatial inequalities but that are also networked to their rural hinterlands, their nations, and the globe. Doing so is of great urgency now, particularly because the isolation and quarantine strategies recommended by health professionals are challenging the social and spatial connectivity aims that have inspired innovation in the urban design discipline, even as they are unmasking new inequalities in living standards and neighborhoods among the city’s most and least privileged populations. There is also the looming question of food insecurity, given disruptions in connectivity between cities and the countryside (6). Landscape architects will need to join with urban planners and designers to reestablish those interrupted networks.

Each one of these sectoral challenges will place the onus on our students to learn how to identify, map, and communicate urban, health, and environmental risks or vulnerabilities in ways that are legible to citizens and city-builders. Through open engagement with citizens themselves, and building on our own local knowledge, we can identify the design and building practices that use the future as a reference point for building better cities today.

Finally, and in addition to the huge commitment to enabling a robust urbanism that makes sense in the context of future ecologies, the pandemic may also force all of us to value and embrace flexibility as a concept in the design of buildings, land uses, and urban infrastructure. This will be a departure from the modernist toolkit of the past. Yet as we move forward, the design disciplines may need to embrace the benefits of informality over formality, if only to allow for dynamism rather than fixity in city form and function.

To be sure, even this unconventional framing of future design action implies a belief in the possibility of conquering risk in ways that may too readily echo modernist sensibilities. To push back against this, it is important to recognize that the notion of risk can be appropriated ideologically, just as has happened with resilience. The stark truth is that risk does not reside only in the domain of science and the “factual.” Risk as a phenomenon or a legible concern is informed by power and social questions, including who has the right or authority to define risk, how risk is distributed, and who pays and who gains from it. In that sense, it is important to avoid the “tyranny of risk” as a defining principle for action, and to understand that discourses of risk can be abused to justify displacement, controls on citizens, limits on space, and other forms of exclusion that challenge the social and equity principles that also frequently guide our work (7).

I close on a note of optimism. The emergence of new risks holds the potential to create new disciplinary synergies and to bring a wide range of experts together to jointly address the multiple vulnerabilities embedded in building typologies, contemporary lifestyles, cityscapes, and the expanding territorial landscapes in which they are all embedded. Universities have long been trying to keep up with the pace of the enormous changes common to what Ulrich Beck called our “global risk society,” but like all institutions they are slow to change (8). At the GSD, we’ve been able to modify and recast our concentration tracks to keep up with and adapt to some of the major developments of our times. The relatively recent “birth” of the Risk and Resilience track, and its ongoing evolution as it prepares students to confront emerging challenges, shows that this is possible in programmatic terms at least.

To stay abreast of our unfolding reality will require continued interdisciplinary interaction and dialogue among the various design, planning, and architectural professionals, along with allies in the social sciences, biological, engineering, technology, and public health professions. Although collaboration has always been central to design practices, the range of risks we face today means we need even more disciplinary partners, beyond the building sciences and the familiar domains of urbanism. The GSD is well-positioned to champion such a mission, and we believe that Risk and Resilience students will be leaders in this ambitious and vital endeavor.

Diane E. Davis is the Charles Dyer Norton Professor of Regional Planning and Urbanism, former Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design, and Area Head of MDes in Risk and Resilience at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

(1) At the time, I co-directed the track with Rosetta Elkin, professor of Landscape Architecture, and since then we have sought to insure that faculty co-heads span the disciplinary silos of the GSD. The faculty most involved in the track over the last several years are Dilip da Cunha and Abby Spinak.

(2) For example, Kaika (2017) has presented a helpful critique of the notion of resilience, especially as it pertains to the context of urban planning.

(3) See: Latour (2020) and Lorenzini (2020).

(4) I have treated the relationship between the concepts of risk and resilience as they apply to urban design and planning practices in Davis (2015).

(5) See: Davis (2012).

(6) For an historical account of the rise of urban food insecurity and its impact on western forms of governance, see: Foucault (2007), 32ff.

(7) For examinations of the concept of risk and its centrality in modernist ways of thinking, see: Beck (1992) and Giddens (2002).

(8) See also: Beck (1992).

Bibliography

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Translated by Mark Ritter. London: Sage Publications.

Davis, Diane E. 2012. Urban Resilience in Situations of Chronic Violence. MIT Center for International Studies/USAID, 134 pp.

“From Risk to Resilience and Back: New Design Assemblages for Confronting Unknown Future.” Topos, Garten + Landschaft, June 2015: 57-59.

Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977-1978. Ed. Michel Senellart, trans. Graham Burchell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Giddens, Anthony. 2002. Runaway World. New York: Routledge.

Kaika, Maria. 2017. “‘Don’t Call Me Resilient Again!’: The New Urban Agenda as Immunology … or … What Happens When Communities Refuse to Be Vaccinated with ‘Smart Cities’ and Indicators.” Environment and Urbanization 29, no. 1 (April 2017): 89–102.

Latour, Bruno. 2020. “What Protective Measures Can You Think of so We Don’t Go Back to the Pre-Crisis Production Model?” Translated by Stephen Muecke. Versopolis Review, April 7, 2020.

Lorenzini, Daniele. 2020. “Biopolitics in the Time of Coronavirus.” In the Moment (Critical Inquiry), April 2, 2020.