Niall Kirkwood Appointed Charles Eliot Professor of Landscape Architecture

The Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) announces Niall Kirkwood as the Charles Eliot Professor of Landscape Architecture, effective January 1, 2024. Established in 1926 by alumni in honor of former Harvard president Charles William Eliot (AB 1853), this professorship recognizes Kirkwood’s 40 years of service to the University. Niall Kirkwood is also currently the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs.

Kirkwood was educated and licensed as a professional landscape architect and architect in the United Kingdom, and as a professional landscape architect in the United States. From 2003–2009, he was the thirteenth Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, the oldest such program in North America, founded in 1901 by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and Arthur Shurcliff. From 1999–2003 and 2005–2007, he was Director of the Master in Landscape Architecture Degree Programs (MLA), and from 1999–2003, he was the coordinator of the “Design and Environment” track of the Master in Design Studies Program (MDes).

“Niall has consistently devoted himself to teaching GSD students how to tackle–through cultural awareness, through design, and through remediation–seemingly impossible contemporary sites: brownfields, superfund sites, landfills, and sites of extraction. Niall teaches advanced option landscape design studios and offers lecture courses, workshops, and seminars on the interrelation of design and technology in Landscape Architecture, Planning and Design,” says Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture. “The scope of Niall’s teaching, research, publishing, and landscape consulting practice all emphasize a broader understanding of current and emerging technologies from landscape and environmental engineering and how this understanding can best result in more creative, progressive, and ethical design work in the fields of landscape architecture and urban planning and design.”

“My career at the GSD, like that of so many of my colleagues, has risen to the global challenges before us—and with effectiveness, functionality and, we hope, artfulness!”, Kirkwood says. “I have found with support from the school’s leadership we have addressed them with a breadth of vision and striking creativity and in doing so laid the foundations and structure of the unique pedagogy and ethos that is the GSD. Through this honor, I am happy to be linked to the history of the larger University as well as to the advancement of teaching and research at the GSD.”

Kirkwood was elected a Member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and Architectural Registration Council of the United Kingdom (ARCUK) in 1978, an Associate Member of the Institute of Landscape Architects, United Kingdom (ILA) in 1988, a Member of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1989 and was made a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects (FASLA) in 2009.

Niall also chairs the GSD Faculty Review Board and Academic Misconduct Panel and has served as a faculty member of the Harvard Medical School Center for Health and the Global Environment, the Harvard University Center for the Environment, and a member of the faculty steering committee of the Harvard Global Health Institute. He currently serves as the GSD representative on Harvard University’s Title IX Policy Review Advisory Committee and the Vice Provost for Advanced Learning’s (VPAL) Planning Council.

Kirkwood holds courtesy academic appointments including Distinguished Visiting Professor, Tsinghua University, Beijing; Founding Professorship and Dean of Landscape Architecture, School of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing University (BUCEA), Beijing,vand is a Member of Academic Advisory Board of Beijing Advanced Innovation Center of Urban Design for Future Cities. During Fall 2017, he was on sabbatical at Smith College, Northampton, MA, in the Landscape Studies Program as the William Allen Neilson Visiting Professor. He was recognized for his global leadership in the area of post-industrial regeneration and brownfields by an honorary Doctor of Science (DSc.) from the University of Ulster, Belfast, Northern Ireland, in 2009.

Kirkwood is currently Deputy Editor in Chief of Landscape Architecture Journal (2020–present) and formerly Advisory Editor, (2015–2020, Beijing) was formerly Editor-in Chief of Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning (2015–2018, Bangkok), Managing Editor, Worldscape Magazine, Chief Editor, RISE Journal (2015–present, Seoul). His essays and articles on design research, practice and teaching have been published in Landscape Architecture Magazine (USA), Landscape (UK), Journal of Chinese Landscape Architecture, Landscape Architecture Korea, Business World India, City Planning Review: Journal of City Planning Institute of Japan, Landscape Architecture Journal (China), Eco City and Green Building Journal, Landscape Record, China, Worldscape (China), Environment and Landscape.

Announcing the Harvard GSD Spring 2024 Public Program

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) announces its Spring 2024 schedule of public programs and exhibitions, many of which offer interdisciplinary perspectives on history, memory, and the natural world. Writer and professor Christina Sharpe raises foundational questions for a world in crisis in her talk “What Could a Vessel Be?”, part of her ongoing consideration of the conceptual and material nature of vessels (February 13). Educator and historian Lauret Savoy discusses settlement, race, migration, and natural history in America in her lecture (March 26), while architect, composer, and musician Timothy Archambault interweaves reflections on architecture and Indigenous music traditions in his Rouse Visiting Artist Lecture (April 11). Presenting his Wheelwright Prize research project, “Being Shellfish: Architectures of Intertidal Cohabitation,” Daniel Fernández Pascual, co-founder of Cooking Sections, examines the intertidal zone and its potential to advance architectural knowledge (March 5).

New ecological perspectives are central to this spring’s programs. With keynote talks by Anita Berrizbeitia and Ned Friedman, the conference Forest Futures: Will the Forest Save Us All? (February 15–16) brings together leading researchers and practitioners to discuss innovations in urban forestry that can benefit public health and environmental justice while mitigating the impacts of climate change. A related exhibition in Druker Design Gallery at the GSD surveys leading-edge forest management projects (January 25–March 31). Elizabeth K. Meyer explores the intersection of landscape architecture and urban planning in the Daniel Urban Kiley Lecture, “Unsettling Sustainability: Landscape Laboratories as Experimental and Experiential Grounds” (February 29).

Additional program highlights include architectural historian Mario Carpo presenting “Generative AI, Imitation, Style, and the Eternal Return of Precedent” for the annual John Hejduk Soundings Lecture (March 28), as well as presentations by architect Marlon Blackwell (February 8) and this year’s Senior Loeb Scholar Malkit Shoshan (February 27). The fourth annual Mayors Imagining the Just City Symposium (April 19) concludes the semester’s program.

The complete public program calendar appears below and can be viewed on Harvard GSD’s events calendar. Please visit Harvard GSD’s home page to sign up to receive periodic emails about the School’s public programs, exhibitions, and other news.

Spring 2024 Public Program

Forest Futures

Exhibition

Druker Design Gallery

January 25–March 31

Marlon Blackwell, “Radical Practice”

Lecture

February 8, 6:30pm

Christina Sharpe, “What Could a Vessel Be?”

Lecture

February 13, 6:30pm

“Forest Futures: Will the Forest Save Us All?”

Conference

February 15–16

Malkit Shoshan, “Designing Within Conflict”

Senior Loeb Scholar Lecture

February 27, 6:30pm

Elizabeth K. Meyer, “Unsettling Sustainability: Landscape Laboratories as Experimental and Experiential Grounds” Daniel Urban Kiley Lecture

February 29, 6:30pm

Daniel Fernández Pascual, “Being Shellfish: Architectures of Intertidal Cohabitation”

Wheelwright Prize Lecture

March 5, 6:30pm

Debra Spark, “Falling Out: Narrating the Neutra-Schindler Story”

Lecture

March 7, 12:30pm

Frances Loeb Library

Jack Halberstam, “Trans* Anarchitectures 1975 to 2020”

International Womxn’s Day Keynote Address

March 7, 6:30pm

Malkit Shoshan and Womxn in Design, “Designing Within Conflict: Building for Peace”

Senior Loeb Scholar Conversation

March 8, 12:30pm

Frances Loeb Library

Petra Blaisse,“Art Applied, Inside Outside”

In Conversation with Grace La, Niels Olsen, and Fredi Fischli

Margaret McCurry Lectureship in the Design Arts

March 19, 6:30pm

Margot Kushel, “The Toxic Problem of Poverty + Housing Costs: Lessons from New Landmark Research About Homelessness”

John T. Dunlop Lecture

March 21, 6:30pm

Lauret Savoy, “Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape”

Lecture

March 26, 6:30pm

Pedro Gadanho, “Priorities Reversed: From Climate Agnosticism to Ecological Activism”

Lecture

March 27, 12:30pm

Frances Loeb Library

Mario Carpo, “Generative AI, Imitation, Style, and the Eternal Return of Precedent”

John Hejduk Soundings Lecture

March 28, 6:30pm

Joel Sanders, “From Stud to Stalled!: Inclusive Design through a Queer Lens”

Lecture

March 29, 12:30pm

Frances Loeb Library

Dan Stubbergaard, “City as a Resource–Cobe’s Current Works on the City”

Lecture

April 9, 6:30pm

Timothy Archambault, “The Silent Echo: Architectures of the Void”

Rouse Visiting Artist Lecture

April 11, 6:30pm

Garnette Cadogan, “‘The Ground Is All Memoranda’: Walking as Register, Responsibility, and Reenchantment”

Lecture

April 16, 6:30pm

“Mayors Imagining the Just City: Volume 4”

Symposium

April 19, 1:00pm

All programs take place in Piper Auditorium, are open to the public, and will be simultaneously streamed to the GSD’s website, unless otherwise noted.

Registration is not required, unless otherwise noted. Please see individual event pages for full details and the most up-to-date information.

Malkit Shoshan Appointed 2024 Senior Loeb Scholar

Malkit Shoshan, Design Critic in Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, has been appointed the 2024 Senior Loeb Scholar. Each year the Senior Loeb Scholar is in residence on the GSD campus, during which time they present a public lecture and engage directly with GSD students, faculty, staff, researchers, affiliates, and Loeb Fellows. The program offers the GSD community opportunities to learn from and share insights with visionary designers, scholars, and thought leaders in a uniquely focused context.

Drawing upon her expertise in design and spatiality in relation to the conflict in Israel and Palestine, Shoshan will explore what building for a lasting peace can mean now. Her deep relationship to the School, as a current member of the GSD faculty, will enable Shoshan to facilitate discussions about this multifaceted theme over a period that extends beyond that of a typical Senior Loeb Scholar. She will deliver the annual Senior Loeb Scholar public lecture, titled “Designing Within Conflict,” on Tuesday, February 27 at 6:30 pm (Piper Auditorium). She will also lead the Senior Loeb Scholar Conversation, “Designing Within Conflict: Building for Peace” (Frances Loeb Library), on Friday, March 8, 12:30pm, as part of a conference organized by Womxn in Design, a student-run organization at the GSD committed to advancing gender equity in and through design. Additional opportunities for dialogue in the Spring and Fall semesters will be announced.

Malkit Shoshan is the founder and director of the architectural think tank FAST: Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory. FAST uses research, advocacy, and design to investigate the relationship between architecture, urban planning, and human rights in conflict and post-conflict areas. Its cross-disciplinary and multi-scalar work explores the mechanisms behind, and the impact of, displacement, spatial violence, and systemic segregation on people’s living environments. Projects organized by FAST promote spatial justice, equality, and solidarity.

Shoshan is the author and map maker of the award-winning book Atlas of the Conflict: Israel-Palestine (010 Publishers, 2011), the co-author of Village. One Land Two Systems and Platform Paradise (Damiani Editore, 2014), and the author and illustrator of BLUE: The Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions (Actar, 2023). Her additional publications include Zoo, or the letter Z, just after Zionism (NAiM, 2012), Drone (DPR-Barcelona, 2016), Spaces of Conflict (JapSam books, 2016), Greening Peacekeeping: The Environmental Impact of UN Peace Operations (IPI, 2018), and Retreat (DPR-Barcelona, 2020). Her work has been published and exhibited internationally. In 2021, she was awarded, together with FAST, the Silver Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale for their collaborative presentation “Border Ecologies and the Gaza Strip.”

Shoshan studied architecture at the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, and the IUAV–the University of Venice. She is currently an international scholar at the Institute for Public Knowledge at NYU and a PhD fellow at the Delft University of Technology. She is on the editorial board of Footprint, the TU Delft Architecture Theory Journal. In 2014, as a research fellow at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Shoshan developed the project Drones and Honeycombs on global processes of militarization of the civic space. The fellowship included the exhibition 2014-1914 The View From Above and a series of seminars and workshops with multiple experts, stakeholders, governmental agencies and NGOs. In 2015, she was a visiting critic at Syracuse University’s School of Architecture and in 2016, she taught the course “Architecture for Peace” at the GSD. Shoshan was a finalist for the GSD’s Wheelwright Prize in 2014.

Disguised Density: An Excerpt from “The State of Housing Design 2023”

This essay is an excerpt from The State of Housing Design 2023, a book published by the Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) and available to purchase through Harvard University Press. A research center jointly affiliated with the Harvard Kennedy School and the Graduate School of Design, the JCHS has published a widely read annual report, The State of the Nation’s Housing , for over 35 years. The State of Housing Design 2023 provides a design-focused complement to this initiative and was the impetus for a half-day event of talks and panels at the GSD. Edited by Sam Naylor, Daniel D’Oca, and Chris Herbert, The State of Housing Design 2023 is organized around 25 themes that characterize design practice today.

In 2016, architect Barbara Bestor used the term “stealth density ” to describe a multifamily residential development that her firm, Bestor Architecture, designed in Los Angeles’s Echo Park. The neighborhood, historically a mix of Latinx families and bohemian artists and writers, was slowly, then very rapidly, gentrifying in LA’s overheated housing market. Any new construction was bound to be suspect—both as a harbinger of displacement and disruption of the old, streetcar-era urban fabric. Although the term “stealth” conveys a contextually sensitive approach, a way to fit into an existing condition, it also reflects the anxieties of a neighborhood in transition. Changing a neighborhood’s physical character threatens both longtime and recent residents.

Bestor drew inspiration from the modest single-family homes and occasional low-rise courtyard apartment buildings that line Echo Park’s hilly streets. Named Blackbirds, Bestor’s complex combines these two typologies to organize a series of duplexes and triplexes around a central parking court. Each building stealthily resembles a single-family home; the design uses pitched roofs and exterior paint color to break up the bulk of larger volumes, so new construction blends into the surrounding scale. “Two free-standing houses are connected by flashing, and the roofline creates the illusion of one house mass,” Bestor explained to the online publication Dezeen. “Three houses, whose separation is masked, has the illusion of being two houses.”¹

Stealth density is just one possible expression of this strategy. The editors of this book chose “disguised density,” and a 2019 Brookings Institution report used the term “gentle density” to argue that replacing detached single-family houses with more homes on a lot could help reduce housing prices in desirable locations without disrupting the neighborhood. This “missing middle” between the stand-alone home and the dreaded apartment tower takes the form of multifamily townhouses, duplexes, and semi-detached structures packed tightly on a lot. “Building more housing on single-family parcels doesn’t require skyscrapers,” noted the report’s authors, Alex Baca, Patrick McAnaney, and Jenny Schuetz.²

Stealth. Disguised. Gentle. With each, language is used to deflect the fears and misconceptions that have accumu- lated around multifamily housing—biases that align multiunit buildings with the past specters of bleak public housing projects. That new development must slip quietly into a neighborhood underlines the long-held entitlement of home ownership and bias of single-family zoning. The Brookings Institution report, for example, notes that Washington, DC, requires special permission for higher density in areas zoned single-family. Zeroing in on zoning-code terminology, the report identifies how the language of the code privileges low-density to “protect [single-family] areas from invasion by denser types of residential development.” Words like “protect” and “invasion” suggest that code is weaponized against outside threats. Indeed, the report’s authors stress that “‘protection’ entrenches economic and racial segregation.”³ Both Blackbirds and Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects’ (LOHA) multifamily housing development, Canyon Drive, follow City of Los Angeles policy guidelines.

The Small Lot Subdivision Ordinance, first adopted by the city in 2005 and amended in 2016, was touted as a solution to increase affordability in a tight market via infill housing. The ordinance included reduced setback requirements and lot sizes. Building more units—in the form of detached townhouses—on a lot zoned multifamily or commercial was meant to target first-time homebuyers, although it is arguable if this plan was truly successful. In early 2022, two-bedroom, two-bath units at Canyon Drive were sold for around $1.4 million each. Although the price is conceivably less than a ground-up, single-family home on the same lot, the units sold for considerably more than the $1 million average home price in Los Angeles.

The authors of the ordinance recognized that increased density and potentially bulky massing indicative of multifamily housing would set off alarms, so a series of design guidelines dictates specific articulations of facades, entryways, and rooflines to prevent blank and boxy edifices ill-suited to the surrounding context. At Canyon Drive, for example, each unit has a unique identity. LOHA inflected the roofs of the townhouses so that each facade resembles a mid- century-modern A-frame perched atop the garage podium. Similarly, in Greenville, Mississippi, the pitched roofs and shaded front porches that characterize the 42 townhouses of The Reserves at Gray Park suggest that individuation is neither simply an appeasement to NIMBYs nor a market strategy, but also a way of establishing identity and dignity for residents.

Composed of one-, two-, and three-bedroom units, the afford- able housing project by Duvall Decker with the Greater Greenville Housing and Revitalization Association serves low- and very-low-income renters. It’s the city’s largest single-unit housing development in more than 30 years.⁴ Here, disguised density works to deflect the stigma historically associated with affordable housing, while demonstrating that an alternative to a detached single-family home might offer more than the suburban ideal. What if the American Dream was not about individual ownership and a green front lawn but, as illustrated at The Reserves at Gray Park, found in shared public spaces designed to foster community interaction and sustainable site planning?

In many ways, disguised density is a study of aesthetics and perception: both a design exercise in vernacular typologies and a strategic game of hide-and-seek. But camouflage can’t always ward off NIMBY critiques. Opponents of the Ashland Apartments in Santa Monica accused Koning Eizenberg Architecture of “shoe-horning too much building into the site” and brought concerns about increased traffic to Santa Monica’s Architectural Review Board.⁵ The opponents were large neighbors—Santa Monica homeowners concerned about the project’s direct impact on their quality of life and property values. Considered a “preferred project” by the City of Santa Monica, the 10-unit development on a terraced hillside reflects higher density than normally allowed under code but was given an exception to incentivize more family housing to the area. Studios and two- and three-bedroom apartments are divided among four structures. According to the architects, the project achieves a density of 30 units/acre by bridging scales between a residential neighborhood (the source of the complaints) and a high-density, mixed-use development along Lincoln Boulevard to the west.

In 2019, the same year that Ashland Apartments opened, Architecture Australia ran an article about architects Hank Koning and Julie Eizenberg, describing their work as “smart, generous and empathetic,”⁶ which is best embodied at Ashland in the abundance of private and shared outdoor spaces that allow residents room to socialize and take advantage of Southern California indoor-outdoor living.

Ashland Apartments sits on a previously unbuilt lot in the center of the block and is edged on three sides by the backyards of adjacent properties. With no street frontage of its own, the other houses in this highly desirable neighborhood mask its overall density. A long, narrow (and contentious) driveway connects from the curb to the under- ground parking lot. The multiyear clash was, literally, a skirmish over “not in my backyard.”

Although density triggers fears of “too big,” “too much,” or “invasive,” at the heart of these kinds of fights is a battle over the continued viability of single- family zoning in neighborhoods, cities, and states where homelessness is on the rise, affordable housing is out of reach, and sprawl is no longer an option. As a paradigm, single-family zoning was built on pastoral fantasies and systems of social and racial exclusion. Bursting the fever dream of individual homeownership and the loose-fit urbanism it produces is bound to provoke conflict. During an event hosted by Laboratory for Suburbia that questioned what “house” means—both as a spatial product and as home— Gustavo Arellano, an Orange County–based journalist who writes on issues of politics, race, and suburbia, suggested we shatter our collective intoxi- cation, using language that verges on revolution. “[I have to] throw this rock into the windows of the dream I have, and other people have, about where we’re at right now” he said, holding up a painted rock from his childhood.⁷

The sanctity of the American Dream is now undergoing arguably radical, even heretical, change. Across the US, states are rethinking the primacy of single-family zoning, which makes it possible to build multifamily housing in residential neighborhoods—with or without stealth, gentle, or disguised density. Oregon passed legislation eliminating exclusive single-family zoning in 2019. California followed in 2021 with SB 9: The California Home Act, which allows for up to four units on a single-family parcel and promotes infill development.⁸ Its passage was not free from pushback. Under SB 9, landmarked and historic districts are exempt, so the City of Pasadena, a place known for both beautiful craftsman homes and racist histories of redlining, proposed an urgency ordinance declaring the entire city a landmark district, a move that garnered critical media attention and a warning by California Attorney General Rob Bonta.⁹

The Outpost, a four-story, 16-unit project in Portland, Oregon, takes advantage of the state’s higher-density policy and sets a new paradigm for both preservation and how we live together. Beebe Skidmore Architects preserved an existing nineteenth-century home on the property and worked with real estate developer Owen Gabbert and co-living platform Open Door to build a mini-tower: two handsome board-and-batten-clad cubes stacked with a twist.

From the outside, The Outpost’s density doesn’t appear particularly disguised. Its contemporary design displays few tropes of contextual sensitivity, like pitched roofs or vernacular overhangs, even though the other house on the site has both. What is concealed, however, is an experiment in communal living. Shared spaces include the kitchen plus dining and living areas. The project also offers a greater lesson, as disguised density asks us to question the sanctity of the single-family home. As reported by Jay Caspian Kang, suburban neighborhoods are more diverse than our collective imaginary.¹⁰ Existing homes contain multiple generations, older single people, or groups of TikTok influencers. Designing multifamily housing within single-family neighborhoods challenges the notion of the nuclear family as the default resident.

Designing with disguised density strategies allows housing to respond to shifting social and urban planning realities. But is it enough? Well-designed, dense, “missing-middle” housing is necessary to address scarcity and affordability; our language shouldn’t hide the urgency. Disguised density may yield too much agency to NIMBY anxieties and, in doing so, favors modesty over the true need for larger, multiunit buildings.

- “Bestor Architecture Uses ‘Stealth Density’ at Blackbirds Housing in Los Angeles,” https://www .dezeen.com/2016/09/28/bestor-architecture-blackbirds-housing-stealth-density-echo-park-los-angeles/.

- “‘Gentle’ Density Can Save Our Neighborhoods,” https://www.brookings.edu/research/gentle-density-can-save-our-neighborhoods/.

- Ibid.

- “$224K Grant from Planters Bank and Trust and FHLB Dallas Creates 42 Homes,” https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/2018061500 5840/en/224K-Grant-from Planters-Bank-and-Trust-and-FHLB-Dallas-Creates-42-Homes.

- Construction of Santa Monica Apartment Building Appealed,” https://www.surfsantamonica.com/ssm_site/the_lookout /news/News-2015/January -2015/01_23_2015_Construction_of_Santa_Monica _Apartment_%20Building _%20Appealed.html.

- “‘Smart, Generous and Empathetic’: The Housing Projects of Koning Eizenberg Architecture,” https://architectureau.com/articles/hank-koning -and-julie-eizenberg/.

- “Sprawl Session 3: House as Crisis,” https:// laboratoryforsuburbia.site /SS3.

- “Senate Bill 9 Is the Product of a Multi-Year Effort to Develop Solutions to Address California’s Housing Crisis,” https://focus.senate .ca.gov/sb9.

- Attorney General Bonta Puts City of Pasadena on Notice for Violating State Housing Laws,” https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases /attorney-general-bonta-puts-city-pasadena-notice-violating-state-housing-laws.

- “Everything You Think You Know About the Suburbs Is Wrong,” https://www.nytimes.com /2021/11/18/opinion/suburbs-poor-diverse.html.

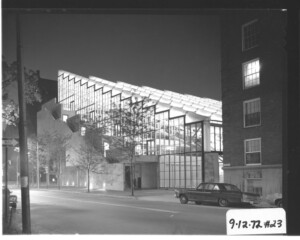

The Plan for a More Sustainable and Accessible Gund Hall

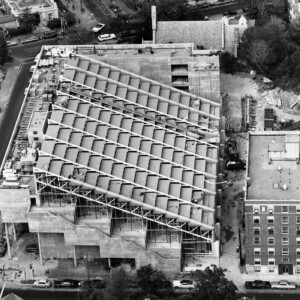

This fall, teams of workers at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design began the first stage in an ambitious renovation of Gund Hall that will be underway through summer 2024. While preserving and updating the School’s iconic main building, the renovations will also vastly increase its energy efficiency. Beyond enhancing the GSD’s core facility, the overall project will model best practices for updating and sustaining mid-twentieth-century buildings.

Designed by John Andrews, Gund Hall first hosted students and faculty in 1972. At the heart of the building are the trays, a five-storey glass-enclosed studio block that serves both as work space and as a center of student community and engagement. In his recent book John Andrews: Architect of Uncommon Sense, Paul Walker writes, “Gund Hall’s famous ‘trays’ came from the priority that Andrews himself gave to the studio as the center of design education.” The trays have retained their vital role at the GSD as one of the most innovative spaces for design pedagogy even as building technology has advanced over the decades. Gund Hall is “largely sheathed in extensive uninsulated glazing systems and minimally insulated exposed architectural concrete,” according to David Fixler, lecturer in architecture at the GSD and an architect specializing in the conservation and rehabilitation of twentieth-century structures. Gund Hall’s existing uninsulated envelope contributes to high energy consumption that translates directly to expensive energy bills, occupant discomfort, and elevated maintenance costs.

Fixler is chair of the Building Committee, which consists of GSD faculty representing the three core disciplines at the school and is charged with overseeing the renovation project.1 “One of the great rehabilitation challenges of our era,” he said, “is to dramatically improve the durability and sustainability of mid-twentieth-century structures while maintaining the architectural essence and character-defining features of these buildings.”

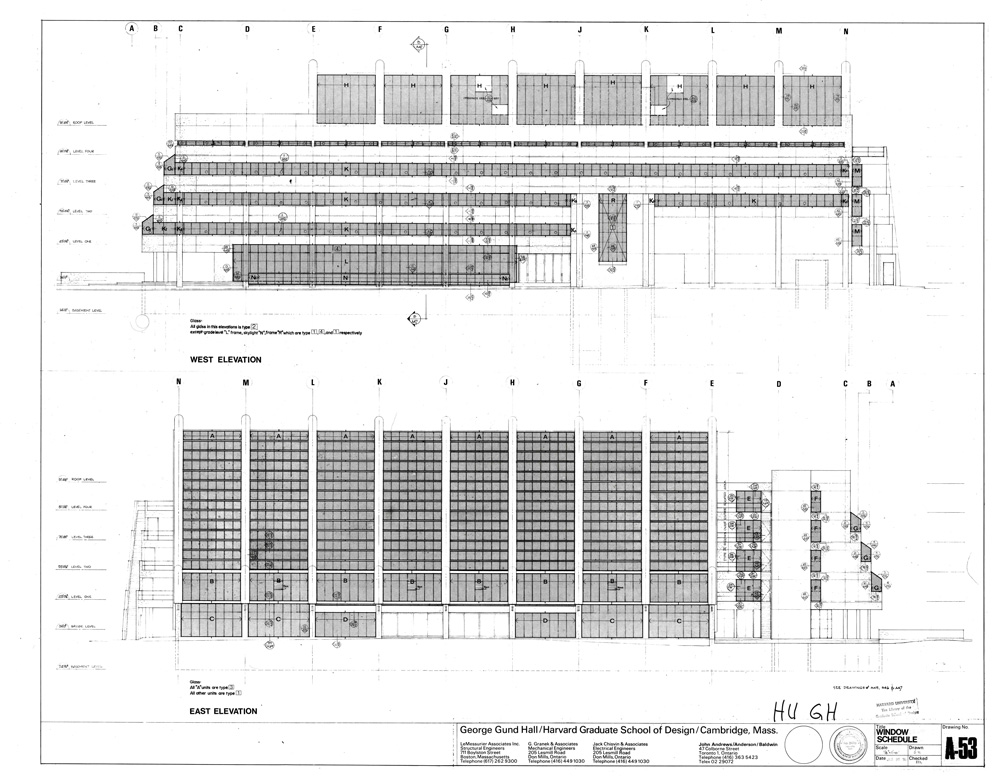

The project’s design is being led by Bruner/Cott Architects, a firm specializing in adaptive transformation and historic preservation. Expert in working with buildings of this period, Bruner/Cott Architects have previously worked with Hopkins Architects and Harvard Real Estate to convert the 1960–1965 Holyoke Center into the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Campus Center. They are part of a large, multi-disciplinary design and construction team that has developed a highly iterative and collaborative process to ensure sound, timely delivery of a state of the art product.2

The renovation process began this fall with a phase to test the design and installation strategies for the upcoming reglazing of the trays. A temporary walled-off “laboratory” has been built in the Pit, a multiuse space in Gund Hall. The mock-ups installed in this laboratory—located on the southeast corner of the building, and including one clerestory section—will be used to assess three replacement glazing systems.

The systems under evaluation include a high-performance double glazing at the east facade slope; a triple glazing at the vertical east facade and clerestories; and a hybrid vacuum-insulated glass (VIG) composite that adds a third layer of insulating glass to the north and south curtain walls. Expectations are especially high for the VIG hybrid, which is not used widely in the United States, but has a strong track record in Europe. By leveraging the insulating properties of the internal vacuum in a glass sandwich that is overall only a few millimeters thicker than conventional double glazing, the hybrid VIG is capable of unprecedented thermal resistance. These hybrid units can deliver energy performance that is two to four times better than standard insulating glass and up to 10 times more efficient than single-pane glass.

Following this testing phase, the project work will begin immediately after commencement in the spring and finish by the fall semester. The trays will be inaccessible during this period.

Replacement of the glazing systems creates an opportunity to make other needed enhancements, including widening the exits onto the outdoor terraces and making them fully accessible. Improvements made to door, sill, hardware, and exterior landing elevations, along with other studio block modifications, will address accessibility issues and bring the building into compliance with current standards where practicable. New under-tray lighting will provide better illumination and upgrade the working environment for these portions of the studio. In addition to the glazing upgrades, a new system of automatic and manual shades for the south and east curtain walls will help mitigate heat gain and control glare.

While temporarily disrupting this core studio activity during the summer, the renovation project will be instructive in other ways, allowing students to view a renovation project in-action, and ultimately leading to improved workspaces. Fixler calls the renovation “a poster child” for rehabilitating buildings of the 1960s and 1970s, “both in the replacement of the studio glazing with state-of-the-art high-performance systems specifically developed for this project, lighting upgrades, and a campaign of careful, targeted concrete conservation.” He continued, “the revitalized studio block will stand as a proud statement of the GSD’s commitment to honor and enhance the legacy of John Andrews, while delivering a significant upgrade in energy performance and occupant comfort.”

- 1. Past and present members of the Building Committee include, Anita Berrizbeitia, professor of landscape architecture; Gary Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture; Grace La, professor of architecture and chair of the Department of Architecture; Mark Lee, professor in practice of architecture; Rahul Mehrotra, professor of Urban Design and Planning and the John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization; Farshid Moussavi, professor in practice of architecture; Holly Samuelson, associate professor of architecture; and Ron Witte, professor in residence of architecture. ↩︎

- 2. Other members of the design and construction team are Vanderweil, mechanical and electrical engineers and energy modeling; LAM Partners, lighting; Simpson Gumpertz & Heger (SGH) structural, waterproofing, and façade engineering; Shawmut Construction, construction management and prime general contractor; A&A Window Products, Design Assist and installation; Redgate Real Estate, project management; and Heintges, BECx services. ↩︎

Harvard GSD Announces 2024 Wheelwright Prize Cycle

The Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) is pleased to announce the 2024 cycle of the Wheelwright Prize , an open international competition that awards 100,000 USD to a talented early-career architect to support new forms of architectural research. The 2024 Wheelwright Prize is now accepting applications. The deadline for submissions is Sunday, February 4, 2024.

The annual Wheelwright Prize is dedicated to fostering expansive, intensive design research that shows potential to make a significant impact on architectural discourse. The prize is open to emerging architects practicing anywhere in the world. The primary eligibility requirement is that applicants must have received a degree from a professionally accredited architecture program in the past 15 years. An affiliation with the GSD is not required. Applicants are asked to submit a portfolio and research proposal that includes travel outside the applicant’s home country. In preparing a portfolio, applicants are encouraged to consider the various formats through which architectural research and practice can be expressed, including but not limited to built work, curatorial practice, and written output.

The winning architect is expected to dedicate roughly two years of concentrated research related to their proposal, and to present a lecture on their findings at the conclusion of that research. Throughout the research process, Wheelwright Prize jury members and other GSD faculty are committed to providing regular guidance and peer feedback, in support of the project’s overall growth and development.

In 2013, the GSD recast the Arthur W. Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship—established in 1935 in memory of Wheelwright, Class of 1887—into its current form. Intended to encourage the study of architecture outside the United States at a time when international travel was difficult, the Fellowship was available only to GSD alumni. Past fellows have included Paul Rudolph, Eliot Noyes, William Wurster, Christopher Tunnard, I. M. Pei, Farès el-Dahdah, Adele Santos, and Linda Pollak.

The GSD awarded the 2023 Wheelwright Prize to Jingru (Cyan) Cheng for her proposal, Tracing Sand: Phantom Territories, Bodies Adrift. Cheng’s research focuses on the economic, cultural, and ecological impacts of sand mining and land reclamation, and her project assesses the fundamental role of these processes in the built environment and human communities.

An international jury for the 2024 Wheelwright Prize will be announced in January 2024 via Harvard GSD’s website. Applicants will be judged on the quality of their design work, scholarly accomplishments, originality and persuasiveness of the research proposal, evidence of ability to fulfill the proposed project, and potential for the proposed project to make important and direct contributions to architectural discourse.

Applications are accepted online only, via the Wheelwright Prize website ; questions may be directed to @wheelwrightprize.org .

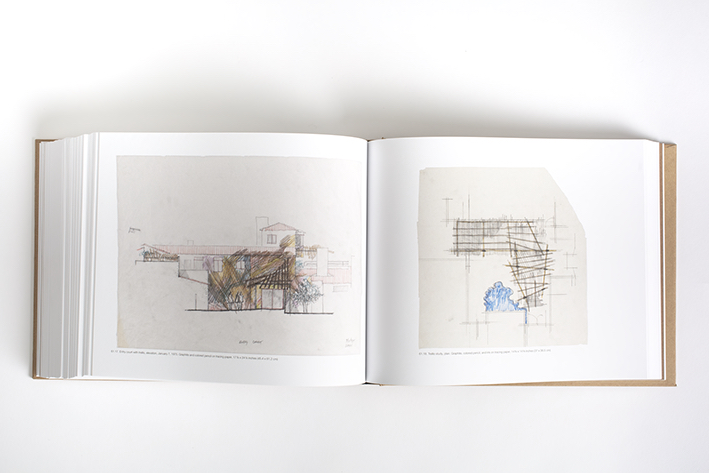

Architect of the Two-by-Four: Jean-Louis Cohen on Frank Gehry’s Drawings

In 2020, Cahiers d’art published Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Vol I, 1954–1978 , the first in a planned eight-volume series devoted to the Los Angeles–based architect. Gehry studied city planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and received an honorary doctorate from the school in 2000 and the Harvard Arts Medal in 2016. The monumental project of cataloging Gehry’s drawings was overseen by the preeminent scholar Jean-Louis Cohen , who served as the Sheldon H. Solow Professor in the History of Architecture at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. A frequent guest at the GSD, a cherished mentor for students in the design fields, and an incomparable historian, Cohen passed away in August 2023. Upon the publication of the first volume of the Gehry catalogue raisonné, Cohen spoke at the GSD with Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology and Director of Doctoral Programs. Cohen’s remarks, edited for length and clarity, are presented here.

Why Gehry?

Why spend an enormous amount of my time working in detail on the work of Frank Gehry? I will simply say that Gehry is unquestionably one of the few architects who have completely revolutionized the discipline of architecture in the past 40 years. I will give two obvious examples: his own house in Santa Monica, of 1978, completely challenged the very core of domestic architecture. It introduced a totally shocking aesthetic register in what was then considered a materially conservative realm. Then, of course, the Bilbao Guggenheim: a building that completely changed the perception of a city. At the same time, it provided a different way of looking at the museum itself, with the design and construction both innovating in many ways. Gehry has left game-changing buildings, both small and big, throughout his career, including his latest projects.

Frank Gehry was also an old acquaintance of mine. For many years in the ’70s, as a student and young teacher, I couldn’t come to this blessed country because of my political affiliation. I was a Red, and Reds were not given serious visas. Suddenly, with the election of Mitterrand, this rule was lifted, and I made my first trip to the US. I met Peter Eisenman in New York. As I was going on to Los Angeles, he advised me to visit with a guy who was doing strange things in his backyard. This was July 1981, and Gehry and I became friends and have remained friends.

Why this book project? This brings us to a Parisian scene of the 1920s, the creation of a journal called Cahiers d’art by Christian Zervos, who was a Greek-born critic and historian with some independent wealth. He was behind the famous 4th Congress of International Architecture and its travel from Marseilles to Athens in 1943. Zervos created a journal in which art, architecture, ethnography, cinema, and music were discussed, with great people writing on architecture. More importantly, he produced between the ’30s and the ’60s, a 46-volume catalogue raisonné of Picasso’s paintings.

Cahiers d’art was resurrected around 2010 by Staffan Ahrenberg, a Swedish-Swiss art dealer and philanthropist. He developed other projects while republishing the journal, including a catalogue raisonné of Ellsworth Kelly’s paintings, curated and written by Yve-Alain Bois. (As you see, it’s a sort of French story all around.)

In architecture, the idea of doing traditional oeuvre complete is less common than in the visual arts. The concept of a catalogue raisonné based on architect’s drawings arose. It would catalog projects by drawings, and, preferably, hand drawings–not the drawings of the computers in an office—and in particular the study sketches.

There were only two obvious candidates, Álvaro Siza and Gehry. We decided to work with Gehry, and what followed was a very complex story. The number of volumes was set at eight from the beginning, and since we began Gehry has made many more projects. To give you a figure, Frank Lloyd Wright built 400 projects. Le Corbusier built 75, if you count Pessac, with its 150 dwelling units, as one. Gehry has built probably 170 out of 400-plus he has designed. (No one beats the world record of Albert Kahn in Detroit, who built 2,000 structures in the mid-twentieth century.)

Gehry was extremely generous in opening his drawers, at first in his office and in his huge Los Angeles warehouse. Then, a few years ago, the Getty Research Institute bought the first part of Gehry’s production: as he says, from his bar mitzvah to the competition for the Walt Disney Concert Hall in 1987. So, 30 years of work, mostly Los Angeles–related. These materials were later photographed by the Getty when the archives moved up to their Brentwood hill.

I had at my disposal masses of boxes and masses of rolls from the age of paper architecture, of analog architecture. It was a process of opening of the tubes, finding the sketches, and trying to tell a story. Gerhy did not obsessively date drawings day-by-day, so there is some guesswork. I had to enter into the logic of the project by trying to cross-reference drawings with related correspondence and reports to understand how a project came about, what the turning points were, and what were the moments when a project changed.

The first volume is a massive book, 550 pages, printed on very thick paper. It centers on 75 projects, starting with Gehry’s diploma thesis at the University of Southern California in ’54. I tried to document the process for each of them as well as I can. Gehry’s house is the lead project at the end of the first volume. I have also written an introduction on how Frank became “Gehry.” The text is not a mini-biography, but it still takes into account the various features of his training at USC in close contact with landscape designers such as Garrett Eckbo, as well as his later experience with Victor Gruen Associates, working on shopping malls and commercial projects, which had a major impact on his early practice.

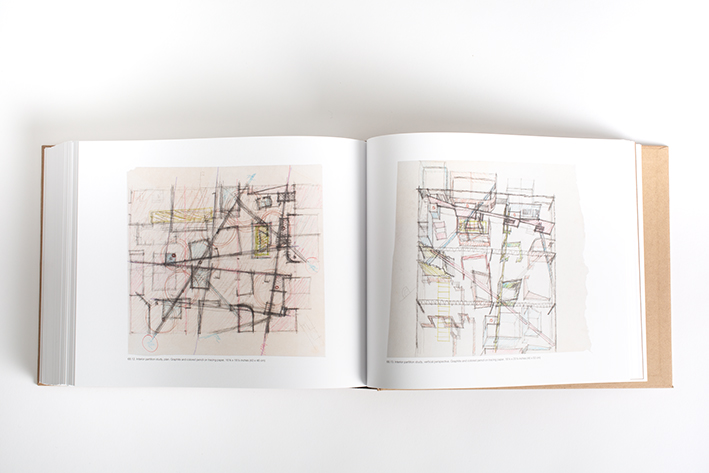

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

The book goes through all the early works, which are relatively unknown, from this first apartment house in Santa Monica, which is documented by relatively small number of sketches, to the more interesting commercial projects. One of my hypotheses is to insist on the sensuality of the commercial projects, in which we find the hand of Frank and the hand of Gregory Walsh, his partner of the time. Walsh had studied with Gehry at USC, and they had trained each other to draw in exactly the same manner in order to fool their instructors and to be able to replace each other for juries. It’s extremely difficult to differentiate the drawings because all the usual tricks for assigning authorship—how trees are made, how figures are made, how the lettering is done—don’t work.

Many drawings in the catalogue, candidly said, are drawings Greg made in the dynamic process of design work. When I had a doubt about a drawing, both guys—Gehry is 93 now; Greg is more or less the same—were unable to decide. “Oh, this must be by you, Frank.” “No, you’re kidding. It’s by Greg.” Then going to Greg, “Oh Come on. This can only be by Frank.” I was sometimes in trouble until the moment when Frank started self-consciously to work on smaller size sheets and really found a language that was only his own.

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

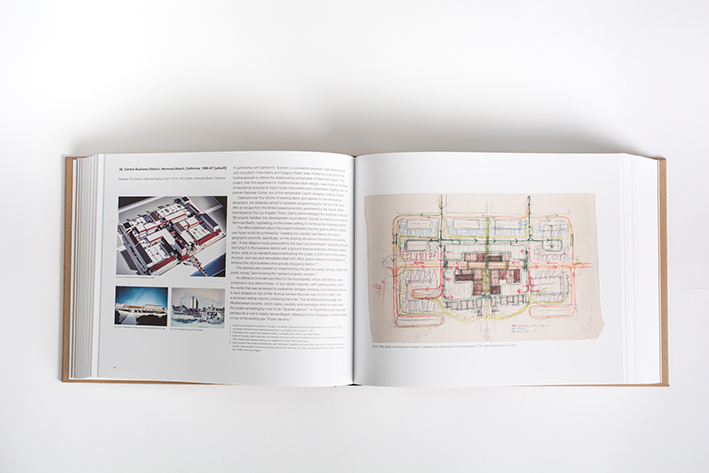

One of the interesting commercial projects is a department store for Magnin done in a series of iterations, the main one being in Costa Mesa in Orange County. Gehry worked at eliminating what he called “the clutter around the goods.” There is a very interesting reflection about the ordering of commercial space, the handling of light, the handling of sound, all of which comes from his training with Victor Gruen. Gehry had the ability to coalesce lots of consultants and work with them over a long time, and this is something that comes from the matrix of Gruen’s design work. He developed an integrative device called a “tree” in the Magnin store. He organized hangers, hanging clothes or shoes, lettering, and direct and indirect lighting all together, to avoid the dissemination of these elements around the space. The handling of the commercial space was, for Gehry, excellent training for the design of museums at a later stage. Dresses were replaced by sculptures, but the same preoccupation at cleansing the space in the museums is evident.

There are moments in this volume we see a sort of anxious quest for an identity, for language. When we look at the projects themselves, we see a series of echoes of other architects. We have Schindler. There is a lot of Wright, even some Le Corbusier. In one project designed for a woman sculptor in Brentwood, it’s clear that Gehry had been impressed by Le Corbusier’s church in Ronchamp, which he had visited during his long stay in France around 1960 or 1961. We see Gehry trying to observe Japanese architecture, but this was mostly the work of Walsh observing Frank Lloyd Wright. He knew everything about Wright, even if he disliked him as a person and was totally hostile to his political positions.

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

The Danziger House, which is very interesting project of ’65, is the first project of Gehry’s that I ever saw, as it was for many others in my generation, precisely because it was published on a page of Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture Four Ecologies in ’71 with an analysis connecting Gehry to Schindler. Banham says that Gehry was the first architect in Los Angeles to return to and to engage with Schindler’s preoccupation with geometry. But one could also see an echo of [Irving J.] Gill’s scheme in Santa Monica here.

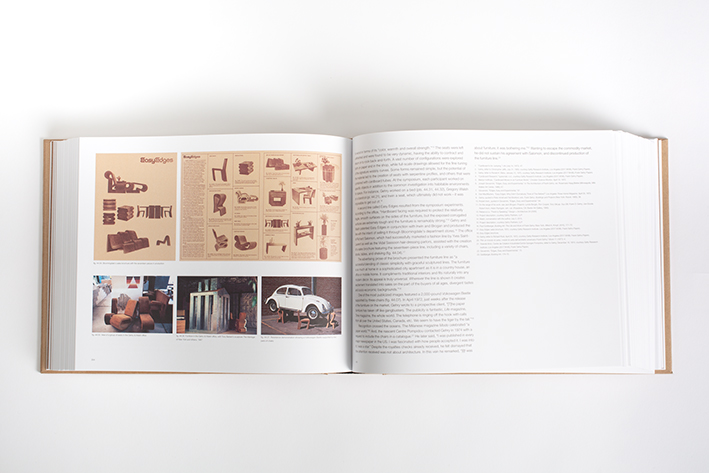

Gehry tells interesting stories about Schindler, whom he had known and with whom he had a real friendship. Throughout the book, one sees how Gehry begins to appropriate what observers, beginning with Banham, have called the “dumb boxes” of Los Angeles: the nearly windowless boxes that line up the boulevards of the city. This is his first, I would say, relatively cubistic project: the Faith Plating Company, which he built even before the Danziger Studio.

Gehry developed contacts with Los Angeles artists. They were friends. He knew their work. They sometimes became patrons, as in the case of Ron Davis. They became role models in his attitude as an architect, and they sometimes provided him more concretely with aesthetic devices and aesthetic patterns, which he would integrate in his work. This is evident in the unbuilt version of a Santa Monica mall: Gehry’s last big commercial project. I can’t help but parallel with Johann Geist’s legendary book of Passagen [Ein Bautyp Des 19. Jahrhunderts], which was being translated into English at that time. If we look at the famous sign of the same Santa Monica mall supergraphic, it’s tempting to imagine a parallel with Ruscha, whose lithograph Gehry had on top of his fireplace, and still has it there.

There were failures also, and I’m mentioning them. Sylvia Lavin has written somewhere briefly about the failure of Gehry to build the house for Ruscha, who was arguably the Los Angeles artist who could be considered as closest to him.

We can also see Gehry building a persona and a discourse based on the rejection of rules, the breaking of rules. He was extremely skeptical about the discourse of architectural aesthetics. Le Corbusier published more than 45 books. Mies wrote maybe 40 articles. Gehry wrote probably three or four articles. He wrote fantastic letters where you find extremely precious lines. The one I prefer is in a letter to a PR person in Los Angeles, a parody of Mies van der Rohe. Gehry writes, writing with a German accent, “I don’t want to be good; I just want to be interesting,” echoing the famous and opposite statement of Mies. There is a corpus of Gehry’s declarations and hundreds of interviews, if there are few articles to speak of.

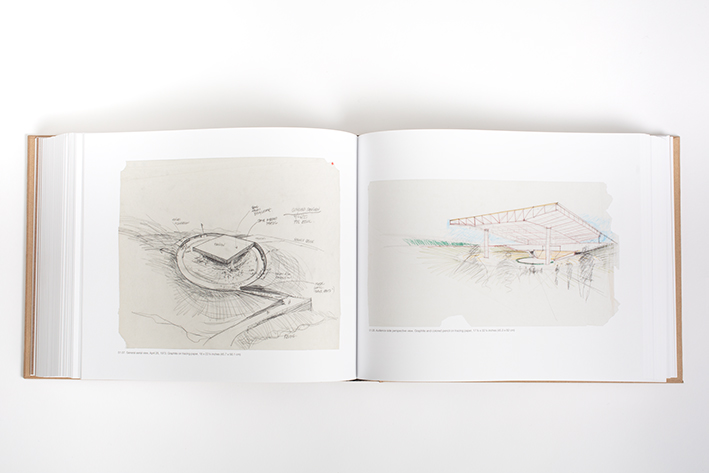

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

In one of those articles, for the National Architectural Press in ’76, Gehry says that he’s at a loss to differentiate between what is ugly and what is beautiful. He theorizes what he calls “cheapskate architecture,” saying that he’s working with materials which are in general, considered as discards. This is clearly something which echoes the work of Rauschenberg in painting.

The beginning of the discourse of fragmentation starts with the idea of breaking down the domestic project into specific spaces, with specific boxes corresponding to the various components of the residents. This unbuilt project, for a Santa Monica gallery owner, is a major one, as is the project for the Jung Institute, which shows autonomous volumes put over a mirror of water.

And of course, there are the drawings of the house in Santa Monica. I found a set of unpublished drawings. One is a very curious attempt I would interpret as using this fence around the initial bungalow, with vertical wood planks that seem to echo of Aalto’s project of the 1930s for Paris and the New York pavilions. Gehry is known for repeating to everyone that he had an early epiphany about architecture in Toronto while listening to an unknown, at least to him, Finnish architect who turned out to be Aalto.

There are many, many sketches of the house, which is a very complex demonstration of all his skills. It’s the project that concludes this first volume—and also the one that brought Gehry into the headlines. Allesandro Mendini’s Domus cover story discussing the project was probably the first really perceptive essay on Gehry.

Volume One is also the history of Gehry discovering, using, and manipulating, and in a way, challenging, teasing the typical frame of Los Angeles domestic architecture. And I will end on a hypothesis, which is probably one of the hidden ones, the many hidden ones in the book: I don’t think that Gehry would have emerged as he did with these first decades of design in a building culture based on steel, or, even less, concrete. A lot of his architecture, many of these architectural decisions and provocative proposals, were based on the freedom given to him by the wood frame. He is an architect of the two-by-four.

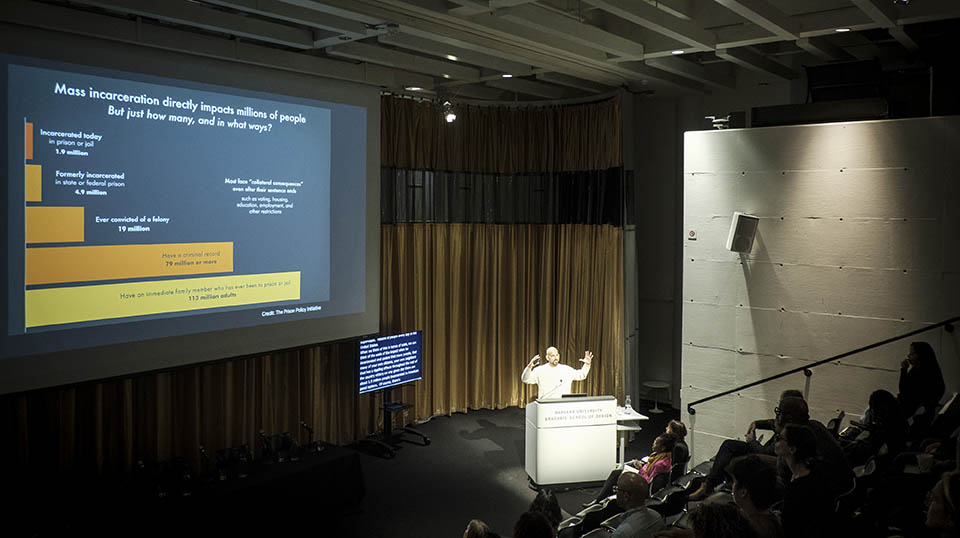

“A Radical Obvious Idea”: “Carceral Landscapes” Confronts the Role of Design in Mass Incarceration

A photograph from the 1950s depicts Chicago’s Cook County Jail in a fragile state. An imposing wall had crumbled, leaving bricks—many of which were produced by inmates themselves—scattered in the yard. Melanie Newport , Associate Professor of History at the University of Connecticut, shared the image as part of “Carceral Landscapes,” a symposium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in October that aimed to foreground the role of architects, designers, and planners in confronting mass incarceration in the United States. The photo of the jail in ruins served as an evocative touchstone for discussion throughout the event. Speakers and audience members alike reflected on the imposing facilities designed by architects to detain millions of people as well as the effort required to unmake that architecture.

Organized by GSD faculty members Lisa Haber-Thomson , Lecturer in Architecture, and Dana McKinney White, Assistant Professor of Urban Design, and co-sponsored by Harvard Law School’s Institute to End Mass Incarceration , the symposium focused on the physical infrastructure of incarceration, highlighting its histories and present conditions as a step toward dismantling an oppressive system. As Newport said, “the gradual escalation of mass incarceration happened brick-by-brick.” Bringing legal expertise and sociological studies together with research on the built environment, the symposium sparked an interdisciplinary conversation about a social problem with multilayered origins and impacts.

“We as designers are culpable in part for the issue of mass incarceration in America,” McKinney White explained in an interview, noting the active role that architects, including major firms, have played in building prisons and jails. “It’s critical that this conversation take place at the GSD because we are in a very influential position,” McKinney White continued, “not just as a school of architecture, landscape architecture, and planning and urban design, but also as a part of Harvard, where conversations about mass incarceration are happening at the Law School and at the Kennedy School of Public Policy. This is a moment of leaning into that conversation and actively talking about our role in it.”

The scope and urgency of the problem became clear through a series of bracing charts shared by Andrew Manuel Crespo , Morris Wasserstein Public Interest Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and Executive Faculty Director of the Institute to End Mass Incarceration. With a per capita incarceration rate dwarfing that of other developed nations, the United States carceral system is an extreme outlier among peer countries. On any given day, nearly 2 million people are incarcerated in US facilities, and millions enter the system every year. Mass incarceration impacts an astonishing number of people: Crespo estimated that the half of Americans have been affected, either by entering the system themselves, living under supervision of a criminal justice system, or having an immediate family member who has. As a phenomenon, mass incarceration is both a widespread and hyper-focused, disproportionally impacting people of color and those living below the poverty line.

While the present justice system may seem intractable, buoyed by appeals to public safety, Crespo emphasized that mass incarceration is a recent phenomenon. Incarceration rates started to spike only in the 1970s and peaked in 2009. Over that time, confinement became a “backstop for problems we can tie to social conditions and social inequality.” He described the need to end mass incarceration as a “radical obvious idea,” one that would require a direct confrontation with deep social problems rather than a continued reliance on carceral “solutions.”

While lawyers and law enforcement officials animate the criminal justice system, architects had a crucial role in creating it. Haber-Thomson introduced the symposium with a critical history of the emergence of carceral architecture. She noted how studies by Michel Foucault and Robin Evans have shaped contemporary perspectives on how modern prison building typologies, including the notorious panopticon design, emerged in industrializing Europe at the end of the eighteenth century. Haber-Thomson argued, however, that such histories of prison must now be augmented by the recognition of longer continuities between mass incarceration and enslavement.

The full history of incarceration is a daunting account of oppression. But it also reveals moments of subversion and strategies of resistance that people in the present can recover. “Every history of these spaces contains contestation,” Newport said. Her study of the Cook County Jail, the largest single-site jail in the country, shows that the facility is far from monolithic and stable. Instead, it contains heterogenous architecture and variable land use patterns that reflect evolving ideas about the role of the jail in society. At times, Newport detailed, “jailed people maintained a degree of public visibility,” with information flowing in and out of the structures. Though increasingly isolated today, Newport emphasized the importance of moments of “porousness,” which exist in living memory, as productive counterpoints to the present.

Some particularly dysfunctional jail facilities in urban centers have attracted national attention, notably Riker’s Island in New York and Men’s Central Jail in Los Angeles. While acknowledging the struggles at these sites, Sarah Lopez , Associate Professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the Stuart Weitzman School of Design, drew attention to the rapid expansion of migrant detention facilities in Texas, which have received relatively little public scrutiny. For those constructing this carceral infrastructure aimed at migrants, “remoteness and invisibility is like a science,” Lopez said. Difficult for journalists and activists to access, these facilities are also embedded in rural communities with few other economic prospects. The promise of revitalizing rural areas is one selling point for the prison industry, though Lopez noted that the anticipated benefits rarely materialize, with profits extracted by major companies. Still, the dependency of rural political districts on the detention economy helps perpetuate the system overall.

How can designers hope to make a difference in these conditions? Crespo noted that the infrastructure built during the prison boom of the 1980s is now aging, with some facilities reaching the ends of their anticipated lifecycles. According to Crespo, architects may have an opportunity to force a change by withholding their expertise, essentially letting the walls of jails crumble, like those in Newport’s photograph. In this environment, disputes about “vocational ethics” will surely arise within the field. Crespo mentioned a pressing example: Should designers help make jails and prisons more humane, for example by bringing the facilities into compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act? Or should the sole focus be on arguing against the incarceration of disabled people in the first place?

The time for pondering such ethical quandaries may be running out, Lopez suggested. She pointed to the rapid pace with which carceral facilities can be constructed in Texas, with sites for more than a thousand detainees erected in as little as a year. She sees a “dystopian future” of scaled-up, dehumanized imprisonment already coming into existence while the architecture profession lags behind. Only in the past few years, Lopez noted, did the American Institute for Architects ban designing for execution facilities and solitary confinement.

As McKinney White said, however, “until we see more development in solution-building, we’re going to have to try out lots of different approaches, innovate, and be willing to go out on a limb with ideas that may not always be favorable.” Such innovations are the subject of respective courses at the GSD that she and Haber-Thomson will lead to foster further discussion among GSD students. The symposium included a workshop for students focused on the writings of imprisoned people and their experiences with architecture, a project that Rachel Fischer, a first-year MUP student, discussed during a brief presentation.

The symposium was a call for designers to stay engaged in finding alternatives to mass incarceration. Far from an abstract problem, the system comprises concrete spaces that are inhabited by people and situated in communities, and that have transformative effects on the land. Still, just as architects and designers played a role in building this infrastructure, the symposium suggested that they can be unbuilt just as readily. As Crespo said, invoking the crumbling walls of Cook County Jail, “things that seem inevitable feel that way until the moment when they aren’t.”

Theaster Gates and Karel Miler’s “Actions”: An Excerpt from “Pairs 4”

Pairs is a student-led journal of conversations that matches subjects with objects, interview with archive. The journal is organized around a diversity of threads and concerns relevant to our moment in the design disciplines, bringing forth candid exchanges and provisional ideas.

For this conversation, featured in Pairs 4 , Isabel Lewis spoke with Theaster Gates, an interdisciplinary artist whose work focuses on social practice and installation art. Trained as a potter and an urban planner, Gates is the founder of the Rebuild Foundation, a nonprofit cultural organization that aims to uplift under-resourced neighborhoods. He is based in Chicago.

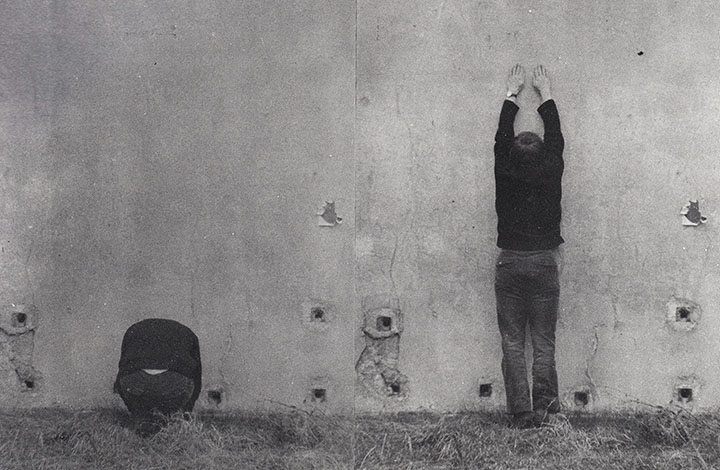

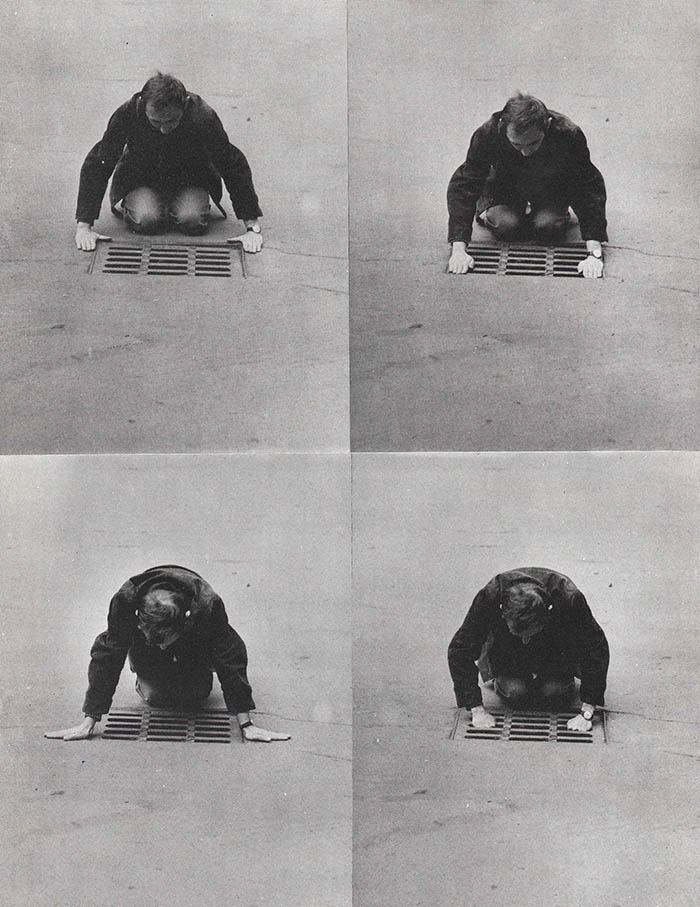

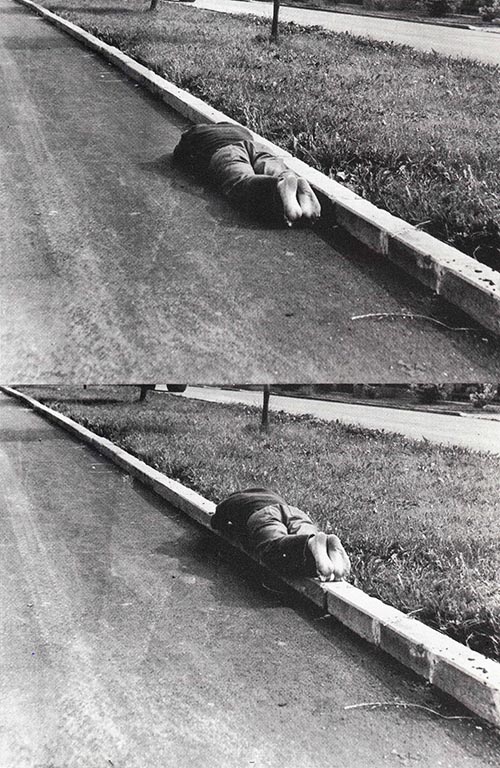

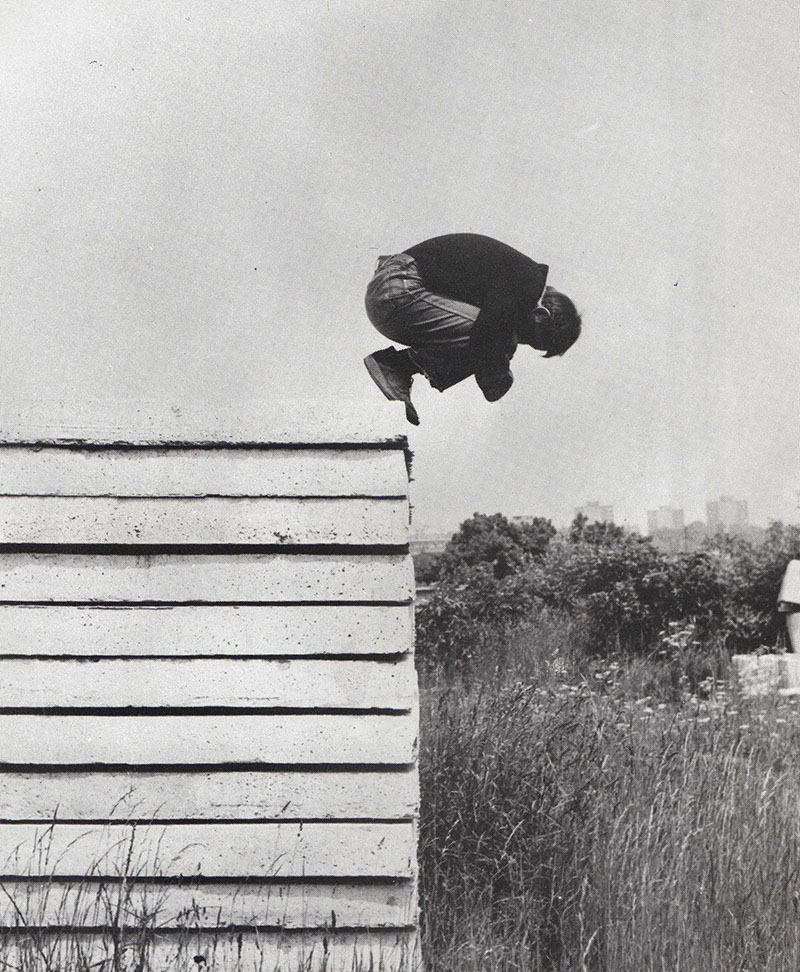

At the center of the conversation is Karel Miler’s Actions, a series of photographs of the artist in semantic translation. Made in Czechoslovakia in the early 1970s, these images were intended to be a form of visual poetry exploring corporality and spatial constriction. A Zen practitioner, Miler is concerned with representations of universal and individual forms.

Theaster Gates Let’s begin.

Isabel Lewis The first time I saw your work, I was nineteen and living in Portland, Oregon. I was taking a sculpture class, and the professor showed us a documentary about your practice. At the time, I was thinking about the way space is affected, how there’s always a social aspect to spatial construction. Your work helped me open the door to the field I’m in now, design and landscape architecture.

Recently, this came full circle, because I went to see the film Showing Up, which is about a young woman, a sculptor, who works at an art school in Portland, which I think is based on the Oregon College of Art and Craft.1 It brought me back to this very specific time and place, this memory of living in that city and trying to figure out what sculpture meant to me. So it had a great impact on me when I saw in the end credits that you contributed art to the film. I was thinking we could start by talking about how memory informs your work.

TG This happens for me, too. Art and artists, they follow us through our lives. The more we learn about ourselves and the more experiences we have, sometimes a work of art shows up and carries a different meaning. It might mean more, it might mean less, but it continues to haunt us and be a part of us. For me, buildings, spaces, and materials also have that haunting effect. No matter what an object is, even the paint that you buy at a store, everything has history. It has an origin story. It has an eternity that precedes you. When you think about acrylic paint or oil paint, even if it’s new, it has a history: the tube that it’s in wasn’t made today. Those processes are in fact part of a found or reclaimed identity, even though it’s a new paint. You buy new wood at Home Depot, and it is not new wood. It’s sometimes preexisting wood that’s been planed again, it’s a tree that has a history, an origin story. For me, saying that a thing is new or has history, it’s everything. You can connect the fact that everything has a history and a narrative to, let’s say, a Buddhist or an Africanist religious belief around animism, or the idea that things have life inside of them. I think what I’m interested in is participating in the truth of the life that is within things.

The more I spend time with materials, the more I think, “Oh, yes, my dad was a roofer. Yes, roofing paper and the materials of roofing are important to me because of that history.” But I also think that those materials have a life of their own, and that if I spend time deeply thinking about that life, then great things could happen with those materials. The South Side of Chicago wasn’t born impoverished. The buildings that are currently abandoned, they weren’t always abandoned. Those buildings have life in them, and it feels like my job is to recognize, exhume, and celebrate the great lives of these spaces. The more I believe the life these buildings have lived was important, the more I want to preserve this, the more I feel like, “This thing deserves to live, deserves to continue to live.”

IL I love that idea of reembodying a place or an image. The striking thing about this set of photos is how physical they feel. I have this bodily response where I imagine myself in these positions and how these things feel. There’s a natural tendency to want to bring life into inanimate objects.

TG Absolutely.

IL It also reminds me of paint, oil paint in particular. We have these names like Siena or Umbrian brown, and those come from the land. That’s the color of dirt in Siena. These materials are defined by their most fundamental origins.

TG Yeah. For every color that’s a natural color, there’s a plant or a mineral or an insect or a bark or a root that’s being crushed and ground to produce the thing that then allows us to produce beauty. I think that those processes and those roots, they have their own beauty. Let’s pull up an image, Isabel.

IL I’m drawn to Limits, as with many of these images, because there’s so much movement that’s implied but not ever shown. You see the beginning and the end of an action, but everything in between is just inferred. I think it goes back to what we were saying about time and timelessness, too. We think of performance as a time-based art, but in its documentation, it becomes a moment completely out of time. When I look at this, I feel it in my body, and it becomes much more spatial than anything else, much more corporeal.

TG I also think that we’re not necessarily analyzing the photograph itself, but the choices behind it. In 1973, Ektachrome was already available.2 We were already in good and saturated color, but to have this image in black and white adds to the austerity, meditation, simplicity, it makes those contrasts pop even more.

IL The artist, Karel Miler, was a Zen Buddhist. That stayed with him throughout his life, even after he stopped working as an artist. A lot of these images are meant to be a translation of poetry or meditation into a representative image. I wonder what you would end up with if you were to translate these images back into language.

TG Measurement is language in that you’re taking a somewhat arbitrary sense of space, and you’re codifying space with lines, and then you’re giving those lines a shared understanding, so that we all agree to what a foot is or what a meter is, what a yard is, we agree to what a millimeter is, and as a result of our shared vocabulary, we’re able to then translate information across time.

IL Does translation feel like an adequate way to describe how you move through different scales, from pottery to neighborhoods to larger urban structures?

TG I think about translation all the time, Isabel. I do. Sometimes when I’m making a work of art and I sit down with a journalist and they look at a tar painting, the first thing they say is, “So your dad was a roofer?” It’s like, “Well, yes,” but the thing that I’m trying to convey is not necessarily about my relationship with my father. There are other, more sophisticated codes embedded in these materials, not just one prescription.

Translation also has to do with our ability to deeply interpret the meaning of a word or moment. I think about translation in the sense that art is a stand-in for my words. It’s a set of codes that goes without the need for my body, and it’s able to say things, sometimes simple things, sometimes more complicated things. That’s cool.

I recently wrote an essay about a dear friend of mine named Tony Lewis, an artist who uses language in his drawings, and it led me to look up the history of shorthand.3 It seems like an abstraction, but people who understand it can translate shorthand into language. If people across languages learn the same shorthands, then you can sometimes know universal shorthand without having to know the language. All of these modes are modes of translation and interpretation. It requires that you have a base knowledge of something, and then you add to that base knowledge a symbol that is universalized. In that sense, Tony’s work reminds me of this international code. It reads as abstraction, but only because most people don’t read shorthand. I’m saying so much right now, Isabel, I’m so sorry.

IL No, no, it’s really wonderful.

TG If we go back for a second to measuring in this image, what I love about it is he’s trying not only to set up the limits of his body, like the length of his hand, but also to show the deep correlations between his body and a crevice, or a crevice and the rise of a stair. I think these things are so relevant for landscape architecture in that sense, because the rise seems incredibly human. When you think about stately stairs, the rise is often short, sometimes the run is super deep. You actually have to take two or three steps for each tread, and it’s interesting to think about how when it gets past the foot, when it gets to three feet or five feet, it reads as grand because it’s bigger than our body.

IL Form and the body have such an interesting relationship to scale. All those books of the architectural standards say that a countertop is going to be this high and a cabinet is going to be this high because a typical body looks like this, but then my mother can’t reach any glasses from the top shelf because she’s not a five-foot-nine male. It’s worth subverting those expectations to measure space by atypical metrics. I made a Klein diagram a little while ago about tables and chairs.4 A baby sitting in a highchair, that’s a chair and a table in one element, with a very prescribed use. But if you’re perched over the kitchen counter, eating takeout from a container, you’re not in a chair nor at a table, and you’re not using the counter as intended. It’s that individual expression, I think, that really makes a place belong to someone.

TG Well, last summer just before going to Japan, I went to a yoga class and the yoga instructor asked, “What do you want to get out of the class?” I said, “I need to be able to sit cross-legged for two to three hours.” What I needed most from yoga was to help me respect the social customs of the dinner table. I knew that moving from my cultural predisposition to a Japanese cultural predisposition would require work, exercise, stretching. I think that sometimes architecture and landscape architecture can inform our new cultural norms. It could allow us ways of getting out of ourselves and maybe new ways of thinking about what dinner could be.

IL The reason why I ended up including this one was because it made me reevaluate the simple idea of holding something in your hand, a perfect weight, a textural variation. By taking a record out of its sleeve or by thinking about how you’re going to shape a pot or play an instrument or cook a meal, all of these things are fundamentally about how we touch the world. It’s not something that’s exportable or translatable.

TG Touch is important because it is one of our first phenomena. Whether it’s the first touch when a baby is born, or consistent touch as a baby ages, or the ability to process information like hot and cold, it’s the way we learn to be in the world and encounter our limits. These images speak to my own interests in the ways they demonstrate how having a sense of how texture affects a viewer of art. People don’t want to just see things; they also want to touch them and know them. To see is to know, but to touch is to also know.

IL Yes, and with the Archive House and the Johnson Publishing Company artifacts, you could make the argument that these objects should be preserved in a museum. But there’s something about flipping through an object that’s very different.

TG Yes, and back to this conversation about the different ways that architectural archetypes show up, who’s to say that the Listening House isn’t a more perfect museum?5⁵ Because we have the ability to touch things—turning the pages of a book, looking closely at a glass lantern slide—we can be more than just witnesses to them by being witnesses through them.

The truth is, when you advance in your research at universities like Yale and Harvard and the University of Chicago, you can gain access to special collections and touch things that other people can’t. I think that sometimes touch is also about who has access and who doesn’t.

IL Even with this magazine, it’s partly because we’re all at the Harvard Graduate School of Design that we are able to have access to these people and to these objects. It’s a privilege. I think the hope is that by doing and sharing this work, we’re making the process at least somewhat more accessible. But it is true that touch is something that you’re very lucky to access. I think there’s probably a lot of lack of touch in the world right now.

TG For me at least, as I was building the Listening House, Archive House, and Black Cinema House, and ultimately the Stony Island Arts Bank, I was definitely thinking about a person’s experience of these different spaces. The experience of that has everything to do with trying to create more access to the place, more access to people. I feel like we’ve at least been successful in helping people gain access. I’m quite proud of that.

IL I’ve been thinking a lot about the way that clay in particular holds memory. It holds fingerprints, and the act of throwing a pot is so intensely physical, really, really hard work. When you hold something in your hands like that and it’s shaped by your hands, it has your imprint on it. But it’s interesting to think about the way that that is scalable through other materials as well.

TG Absolutely. It’s reasonable that when we’re doing renovation projects, if we take out a stone, like a terra-cotta cornerstone, from a building, we can see the marks of the maker. But they might also put in some funny anecdote, or write their name or the date, because these are not actually anonymous objects. They’re anonymous to us because the histories of those materials haven’t always been carried forward. But in fact, from a pot to a large structure, objects often carry the remnants of people’s touch. If you look close enough at most buildings, you’ll see the traces of the people who made them.

IL This is relevant to something I was working on last semester about Julie Bargmann’s work in rehabilitating toxic landscapes. In a landscape project, there’s this dual action of not erasing history but honoring it while also acknowledging that land often has a complicated past. How do we preserve memory in built environments or urban landscapes in a way that feels authentic?

TG I think sometimes art and conceptual practices can help us on that journey. Sometimes, and I think this is what we’ll get to with these photographs, performance and conceptual ideas help us tackle these bigger questions by putting the body present in ways that implicate a site, make you feel more compassion toward the site because of the complexities of the things that happened there.

I remember when Cabrini-Green in Chicago was being torn down.6 There was concern that poor people were being displaced, largely poor Black people, because that land had become some of the most important land in the city for its adjacency to downtown. It’s like, “Well, Black people still deserve the right to live in a place that they’ve been living in for the last fifty years, sixty years, for which nobody gave a damn.” The site has changed over time, but the people haven’t. What do you do when time has shifted people’s stigma of a place?

People who lived in Cabrini Green deserve the right to continue to live there, even if the land is now worth a lot of money. When they were excavating, there was a lot of clay underground. I remember just trying to get access to that site and that clay, to use it as a stand-in for the people who once lived there.

IL I think there’s this notion that a landscape intervention won’t do harm. It’s complicated because there’s one lens that focuses more on the rights of the biome and another on the rights of people. Of course, they go hand in hand.

TG We look to landscape architecture as the solution to neutralizing space and time. It starts with large projects that are government or municipality projects, but then you have private developers and privately owned public spaces.7 In these moments, we need landscape to give us something that is not an office building, not a residential thing. But that safe passage route or that new bike lane or that grove of trees is sometimes still a disruptive act of transferring a community space from one of people in need to one of people that have a tremendous amount. I think protecting green and public spaces is important, and also not using green space or landscape as the thing that disintegrates a certain community continuity is important.

IL What I’m trying to get across is that people can think of landscape as very politically neutering. It’s like, of course, who wouldn’t want landscape beauty in their neighborhood? But I do think that there’s a tendency when any project is approached with this developer-down, top-down approach that erases the individual user. Maybe the only way to really approach this idea is from the inside out, moving from what you can shape with your hands to eventually what can shape you.

TG I think we’re saying the same thing, Isabel, that every urban tool can be a divisive, derisive device that separates and disconnects as much as it can be a tool that aggregates and reconnects. There is no neutral tool, including landscape architecture, and I think it’s really powerful that you’re able to see that. There will be moments where you’ll be on big projects, and it’ll be like, “Fuck!” When we build these new cities, we haven’t given any thought yet to where people are going to commune.They’re building apartment buildings and they’re building bus depots and transit things, but they haven’t thought about places of worship. They haven’t thought about the park where people might do yoga.