Dual-Use: Farshid Moussavi on rethinking residential architecture in the wake of Covid-19

Dual-Use: Farshid Moussavi on rethinking residential architecture in the wake of Covid-19

The pandemic has had an immediate and tangible impact upon urban life—rewiring and, in some cases, completely transforming the daily experience of our cities. Nightclubs, concert halls, and stadiums have gathered dust since mid-March, while car-cluttered streets in city centers have transformed into pedestrianized avenues that teem with bistros and eateries. One of the most far-reaching changes has been that in a very short amount of time, our relationship to work has been completely transformed. Millions of people are suddenly working from home, which has raised many questions for the future of housing design.

“Dual-Use,” Farshid Moussavi’s current studio at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, explores the politics of designing everyday spaces in architecture and the profound impact it has on people’s lives. In an era when residential developments’ cookie-cutter formwork follows private-sector financial systems and reinforces divisions along gender and class lines, Moussavi is interested in subverting that capitalistic demand. By generating new socially inclusive and politically resilient dual-use housing typologies while still satisfying market need, Moussavi adopts an approach that is anchored in real-world problems as well as in the constraints of practice.

According to Moussavi, over the course of the pandemic, we have inadvertently traveled back through time: reverting to a preindustrial, 19th-century housing model, wherein domestic space was also the workplace. Today, office workers roll out of bed, don their work shirts, and find a flattering corner of their home to load up Zoom. A craftworker folds out a workbench from a closet in his studio apartment, while a mother feeds her baby before heading into a spare bedroom that has been repurposed as a hair salon where she receives clients. But working from home is far from a universal right; the pandemic has revealed and intensified inequalities of privilege, labor, and class as not all work can be accommodated in the standard modern apartment.

Moussavi explains that even as the pandemic has pushed to the surface the inequality embedded in the current DIY conversion of domestic space into workspace, it has also presented the idea that another world might be possible. If we abandon the live-work binary that has dictated the development of modern cities, how might new urban residential typologies be enriched with equality, diversity, and resilience and generate new forms of social capital within a truly shared experience of city life? It is an exciting and vital time.

“Generally, left-wing activists, academics, and journalists blame the housing crisis on neoliberal enterprise and the nation-state for abandoning welfare,” says Moussavi. “We need to understand the housing crisis as a typological question too—not just who delivers housing, but how it’s designed, and what can be done differently as well.”

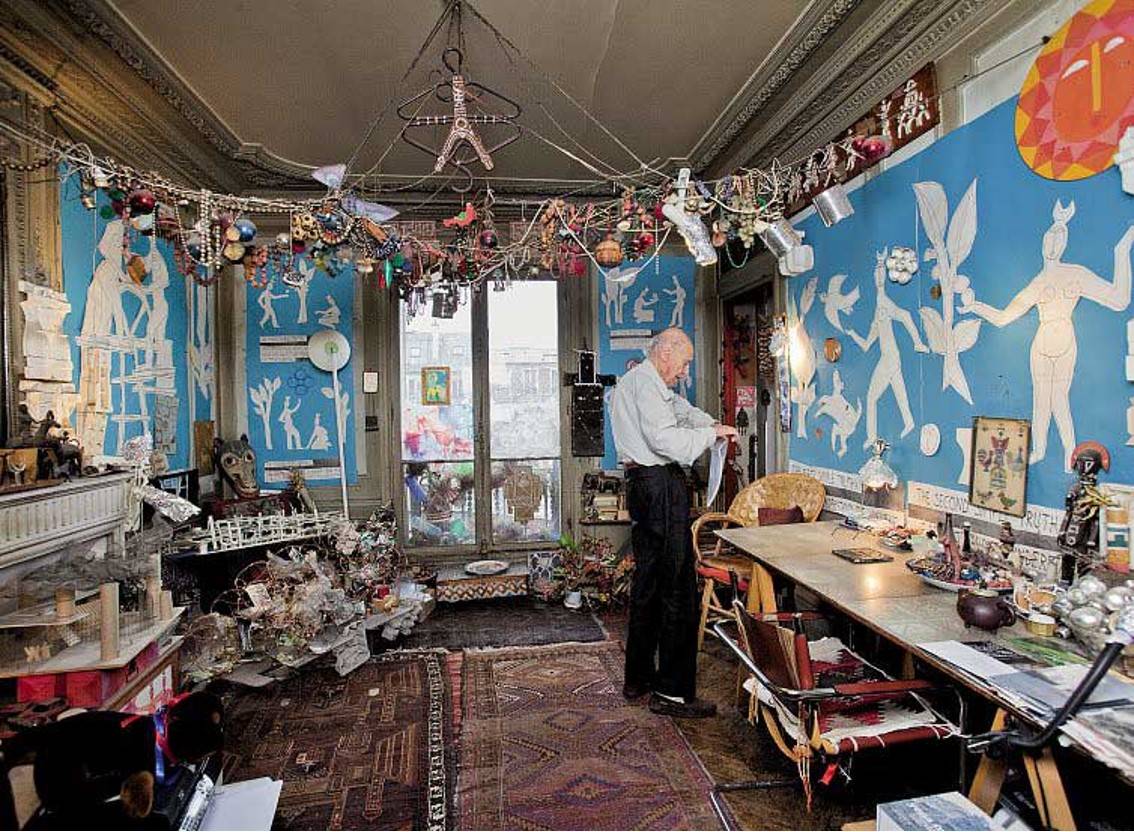

Maison de Verre, Photography: François Halard

Grounding the recent attention placed on dual-use residential architecture within the much longer history of live-work domestic spaces, this studio merges an in-depth historical survey with emerging contemporary criticism. A book identifying eight types of workers that must be taken into account with any dual-use architecture, penned by

Frances Holliss, London-based architect and emeritus reader in Architecture at London Metropolitan University, will be discussed in tandem with case studies ranging from the medieval English house where farmers lived alongside their livestock to recent examples. The Mumeisha Machine in Tokyo, built in 1909, for example, features a long corridor that acts as a transition space between the public street and private residences around back, while the Maison de Verre in Paris, built in 1932, features a three-doorbell system in a doctor’s home office, with separate entrances, so that professional and personal affairs could be carried out in their own designated space.

The studio will also conduct virtual home visits with individuals representing these different home-work setups. And it will hear from architects and historians of architecture and art including

Umberto Napolitano,

Irénée Scalbert, and

Hans Ulrich Obrist on the relationship between housing and spatial diversity, biodiversity, and user-empowerment.

Building upon a sequence of housing studios Moussavi has taught since 2017, “Dual-Use” brings an additional protagonist—

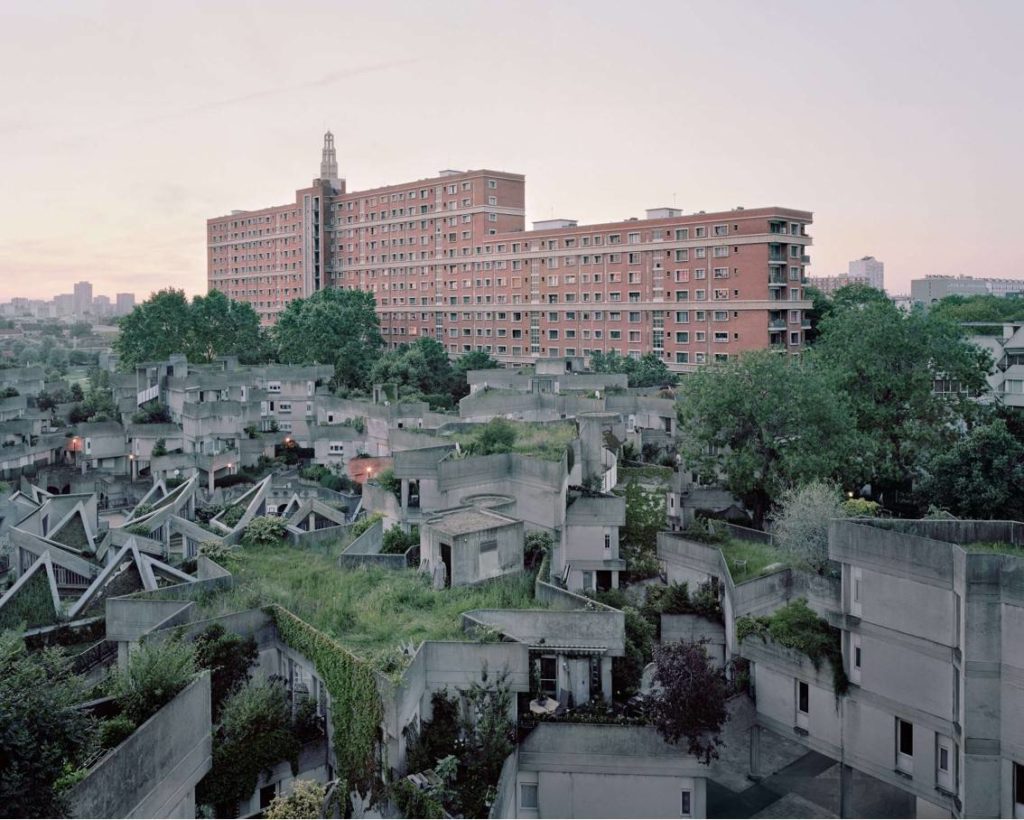

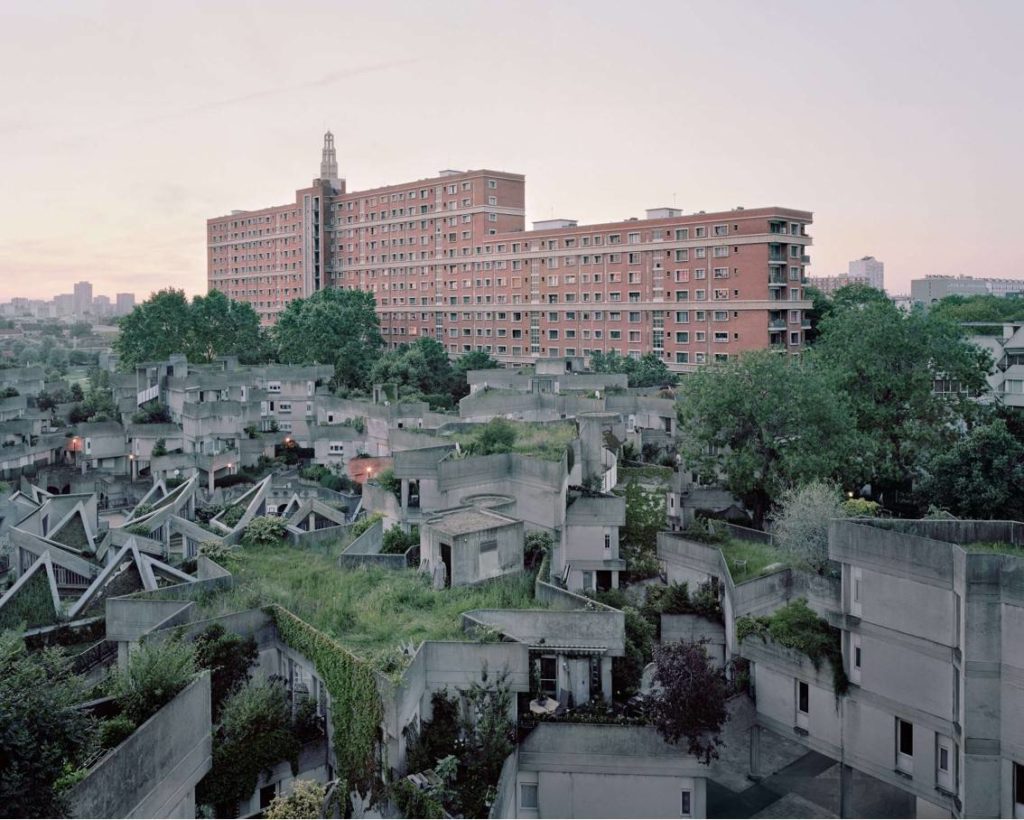

Yona Friedman—to join two French architects researched by the previous studios. The 19th-century Parisian Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s flexible block system, which was investigated in the 2017 studio, is in many ways the antithesis of Jean Renaudie’s spatially complex 20th-century residential architecture, which was investigated in the subsequent studio. In different ways, Haussmann and Renaudie sought to interconnect the design of individual dwellings and the urban space, and focused on user empowerment through the provision of spatial diversity. Yona Friedman offers an interesting comparison point, with a largely theoretical practice that was centered on ideas of self-planning and user-appropriation of space.

Haussmann’s Rue Eugène Sue in Paris. Photograph: Cyrille Weiner.

According to Moussavi, in Haussmann’s system, external consistency is king—long blocks of housing carve out the shape of the city, while the internal elements remain flexible and readily tailored for individual use. A tall lower level with ample natural light provides the perfect site for unique live-work configurations, while the block retains a uniform urban facade. Renaudie, meanwhile, takes the opposite approach in his kaleidoscopic Ivry-sur-Seine, which offers spatially unique dwellings, no two of which are identical. Garden-scale balconies spill out beyond the apartments and provide a strong connection between domestic space and the landscape, between biodiversity and well-being. Malleable space, a flexible boundary between intimacy and community, and multiple types of use are built into Renaudie’s architecture. Friedman, a contemporary of Renaudie, was largely a theorist; projects like the Flatwriter—which could ostensibly help users design their perfect apartment with the press of a button—are far more utopian, untethered to market demand.

“Haussmann begins from the collective, whereas Renaudie departs from the individual—and with a focus on biodiversity in cities, is very relevant to our concerns today,” says Moussavi. “Friedman adds that element of ambiguity. You can learn from all three of them simultaneously and find new applications for their work in the conditions of the present—that’s the beauty of having history behind you, and why I’m a huge fan of precedents.”

Renaudie & Gailhoustet (1969), Cité du Parc, Ivry-sur-Seine, France. Photograph: Laurent Kronental

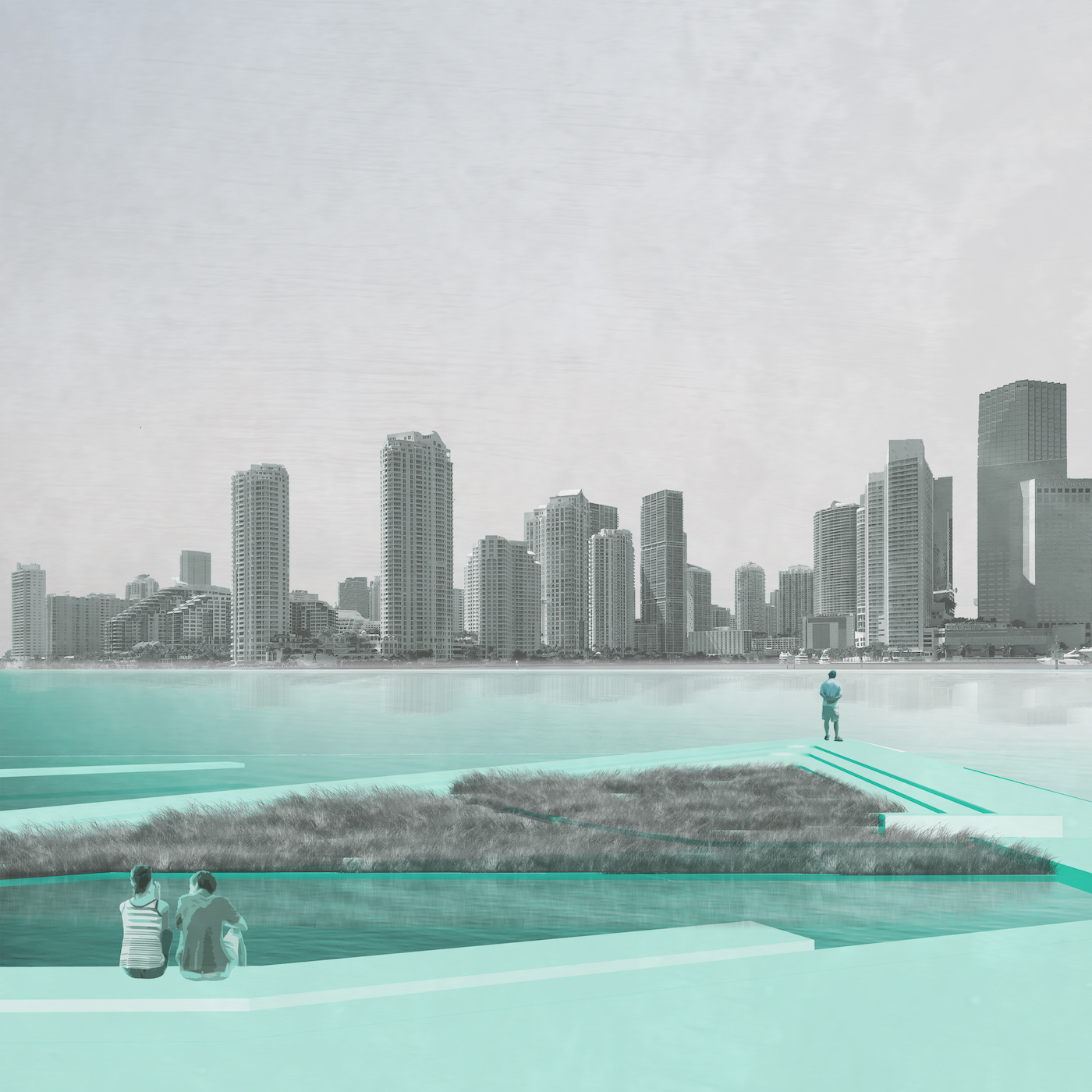

Students will apply their insights to these architects’ work in designing their own dual-use block in one of three sites along La Petite Ceinture—meaning “the little belt” in French—a 32-kilometer stretch of unbuilt land surrounding Paris. Containing the skeletal remains of a 19th-century railway system, the belt has become a space of wild abandon. Known as the mecca of Parisian street art, it also includes areas of slums and overgrown nature. Data from public consultations gathered by

Paris Urban Agency (APUR) shows the belt’s latent potential in the city’s collective conscience: community gardens, affordable housing, and a wildlife reserve were among the suggestions raised by the public.

Based in the 16th, 13th, and 19th arrondissements, these sites vary widely in their own topographies, demographics, and the way they slot into Parisian life and culture. Moussavi explains that the 16th, known as the rich urbanites’ enclave, has the least social housing of anywhere in the capital, while the 19th—the poorest arrondissement in Paris—has the highest concentration of social housing and is the site of former refugee camps. All of the sites are elevated above or face the material ghosts of the railway. Surrounded by Haussmann blocks, parking lots, abandoned stations, and jazz clubs, these are loaded spaces, and the students will need to be surgically precise in their interventions. The future of Paris is waiting.

“We are asking the students to take a visionary position,” says Moussavi. “The pandemic has called into question the efficiency of all the old housing systems, and I think it’s up to us to produce the visions of tomorrow.” The need for alternative typologies for live-work housing is self-evident. According to a study published by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research this summer, 42 percent of the US labor force is currently working full-time from home; this figure climbs to 52 percent in Europe, and 65 percent in the UK. Even when a vaccine is made widely available and we flatten the COVID curve for good, many Fortune 500 companies will continue to allow employees to work from home. The studio is an opportunity to rethink residential architecture and generate new typologies with dual-use apartments that are suited for a variety of households and that place individuals as well as community at their core.

Petite Ceinture, Pont de Flandres Station, Site C. Photograph: Guillaume Choplain.

As seen in the organic evolution of Renaudie’s private terraces into community gardens at the hands of its residents, it’s important for these new typologies to be adaptable: both toward their inhabitants’ fluctuating needs and for unseen future circumstances. In its capacity to incite structural change and transgress the current boundaries of architectural thinking, the pandemic is a catalyst to cross that threshold—but it shouldn’t be understood as an isolated scenario. “Architecture must not be just reactionary,” cautions Moussavi. “Genuinely equitable dual-use domestic space is not just a pandemic issue, but a matter of one’s right to a supportive live-work environment regardless of profession.” This right, and its future rewards of resilient, enlivened communities, persists far beyond the confines of any pandemic.

Hidden Territories: Uncovering the racist legacy of the American landscape

Hidden Territories: Uncovering the racist legacy of the American landscape

The term “landscape” historically referred to pictures of the world—vistas or views—and so it is only a small step to think of landscapes as portraits of society, representations of social imaginaries. What is included and excluded in these pictures is revealing. A landscape can be a tool for a designer: a mirror held up to society that exposes the distortions and repressions that underpin its self-image. In the past months and years, activists have aimed to hold up such a mirror to reveal systemic racism in America. Students, faculty, staff, and guests at the GSD have joined in and sometimes led the way. I have had the opportunity to interview several of these inspiring figures:

Everett Fly,

Jill Desimini,

Linda Shi,

David Moreno Mateos, and

Kathryn Yusoff. Their viewpoints vary, but all agree that adjustments to the disciplines taught at the GSD would help in coming to terms with—and hopefully undoing—the systemic racism revealed across the American landscape.

The architect, landscape architect, and preservationist Everett Fly notes that this process begins with seeing. Fly grew up and now practices in San Antonio, Texas, a city with a palpable sense of heritage embodied in its historic architecture. San Antonio formed Fly’s sensibility, which he hopes more designers will share. “Too often, architects start with their plan by assuming that no other culture has influenced or impacted the site where they’re planning. . . . [They assume a] clean slate—as if no one had ever existed there.” But contrary examples make their way periodically into the news. In 2010 in

Sugar Land, Texas, excavations for a public building project uncovered a mass gravesite containing the remains of 95 former slaves. Similar discoveries occurred in New York and Philadelphia. Important stories had been buried along with these bodies. “For too long we have lived with the assumption that there is nothing significant you need to know about African American history in the landscape,” Fly says.

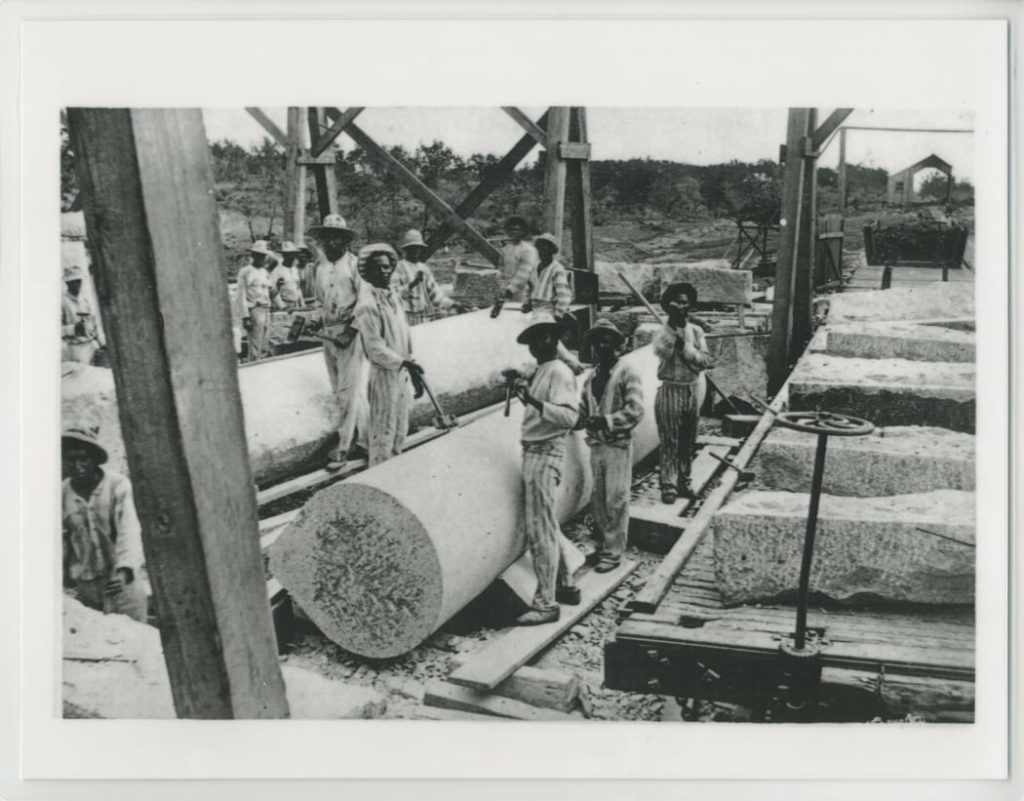

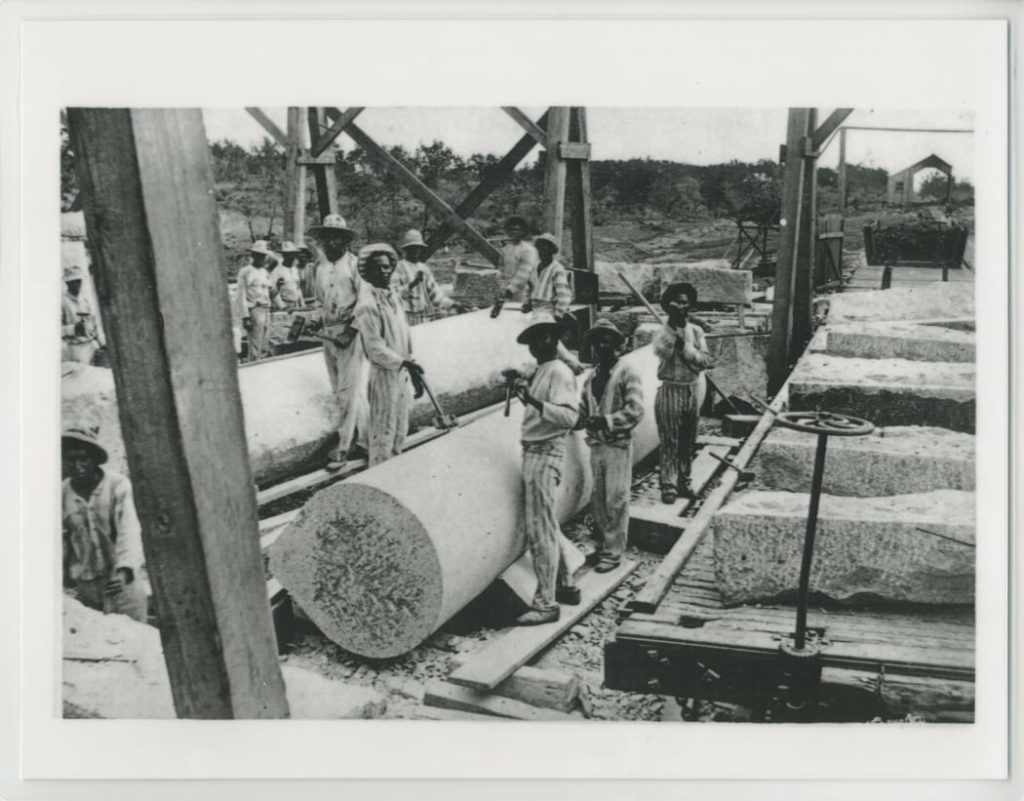

“Prisoners working construction, Convict Leasing Photograph 8.” Couresy: Woodson Research Center: Rice University.

Fly first came to this realization during his education as an architect. Like today, the 1970s was a period of strong social justice movements. At architecture school in Austin, Fly had few Black classmates, and he never heard professors speak about the contributions of African Americans to American architecture. When he began graduate studies at the GSD, Fly enrolled in a history course taught by J. B. Jackson, who was transforming the field of cultural landscape studies. Jackson talked about the role of Indigenous peoples and European immigrants, as well as the impact of railroads and highways within the American landscape. It was far from the clichéd notions of landscapes as merely picturesque views. Still, Jackson only mentioned African Americans a few times. With a streak of defiance, Fly set out to write a term paper on historic Black towns in the South.

By the end of a semester of intense archival work, he had amassed a few dozen brief references. Jackson took a personal interest in the project, which Fly continued into the following semester. He soon included examples scattered across the United States. Fly began sharing his findings at conferences and making contacts in historic preservation. After graduating, a year-long fellowship allowed him to visit many of these towns and go to the cartographic division of the National Archives to seek out obscure maps. “This opened up another vision for me: that you could document these places, despite what people would say, that ‘we don’t have the information’ or ‘you can’t prove that these existed,’” Fly explains. What followed has been a lifelong practice of gently asking people to look again. When greeted with “No, we don’t have anything like that,” he replies: “I bet you do, and you just don’t know how to look for it.”

Fly’s work as a preservationist came together as three components: “Being able to see the communities, being able to find the documentation, and then being able to correlate that with the formal discipline of historic preservation.” This work is as important now as ever. Take cemeteries. Because of discrimination, African Americans were often turned away from public cemeteries, and burials had to take place on private land at some distance from where people lived. These small private cemeteries—”some of our most treasured and valuable sacred places”—are threatened by their obscurity. The first step is to know they exist, then to document them, and finally to engage the mechanisms of historic preservation. Similar to graveyards, early structures such as schoolhouses and churches were built by African American tradespeople rather than architects because pathways to licensure were not available. Seeing and valuing them means also valorizing a thread of African American cultural heritage. “We’re not just protecting the physical structure,” Fly says, “we’re also protecting the legacy of the trades.”

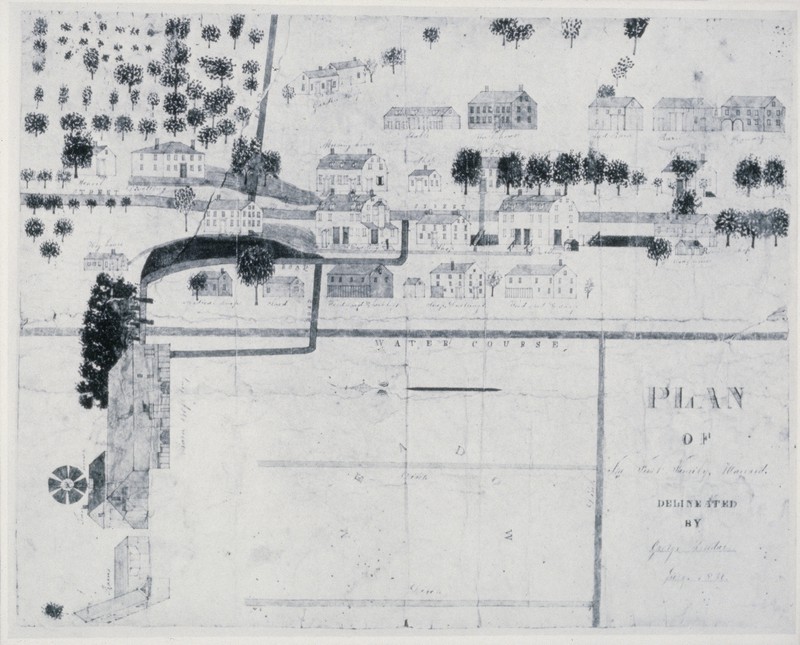

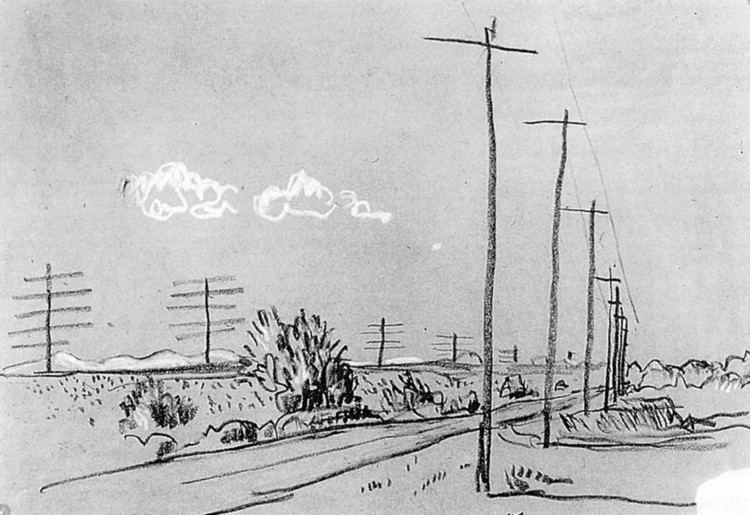

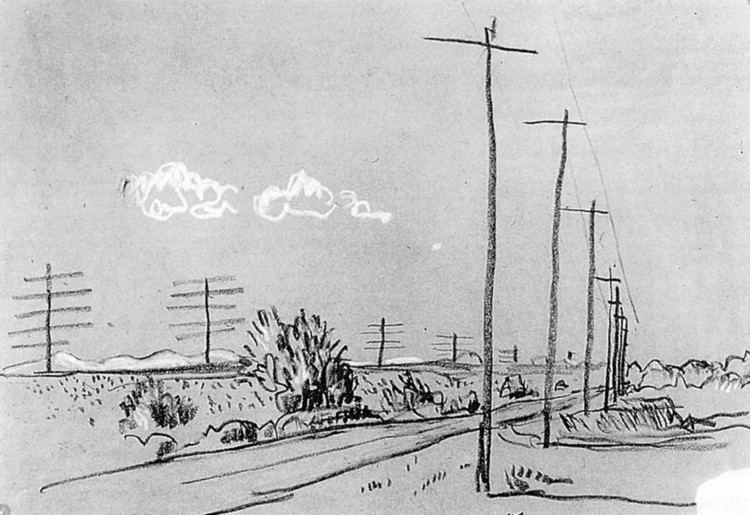

Sketch by JB Jackson

Fly urges more young designers to take an interest in the forgotten cultural heritage that can be revealed across the American landscape. He says that this work begins by always asking the client a question: “How much research have you done ‘below the surface,’ into the layers of history—who lived on this place before today, and how did they live here?” In Fly’s experience, a client will often say that they haven’t done any research. That leaves it up to designers to uncover traces that can be used to “enhance the richness of your design, and help educate your client and the users of the site.” Drawing out more layers adds richness to the picture a landscape presents.

Sometimes whole other types of sites become visible when a landscape is critically reexamined. Jill Desimini, an associate professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, is a champion of vacant lots. Although they are relatively rare in the centers of growing cities, in parts of other cities—Detroit, for example—vacant lots predominate. Desimini emphasizes that this is not a neutral result of market forces, but a dynamic that plays out in countless decisions that are often biased in unacknowledged ways by race and the perceived value of land. “You see aggregations of vacant land in places where residents are people of color, where people are impoverished, where toxicity levels are high due to past decisions, where predatory lending prevails, and where there is a lack of access to resources and services,” she says.

Cities prefer the easy solution of selling land to generate tax revenue. Desimini suggests exploring pathways for “returning land to the neighborhood.” This is not as simple as it sounds—it is a process that must be envisioned and designed. Desimini is currently teaching “From Fallow: Equitable Futures for Landscapes of Injustice,” a seminar at GSD that “partners with a few progressive organizations that care for vacant property.” She says that the open-ended nature of studio research is an asset: “It is a matter not so much of making drastic change to the sites themselves, as drastically reimagining how we approach them.”

Vergara, Camilo J., American Chronicles sign, view NW from Woodward Ave. at Sibley, Detroit, 2009.

, Desimini’s larger project involves changing the way landscape architects work. Her books,

Cartographic Grounds: Projecting the Landscape Imaginary (with Charles Waldheim) and

From Fallow: 100 Ideas for Abandoned Urban Landscapes, are both invaluable resources. Investigation, drawing out possibilities, publishing, and conversation can have a dramatic impact on the course of a discipline. She explains, “I think that we need to be less fickle and faddish and work on projects for a long time and in places for a long time. It is hard to sustain the interest, but I think that it is necessary to build trust.” To undo systemic injustices in the American landscape, a sustained systemic response is necessary.

Linda Shi,

an assistant professor at Cornell’s department of City and Regional Planning, has come to a similar conclusion but from a different direction. As an expert on urban environmental governance, Shi examines and suggests planning policies for addressing climate change while simultaneously improving social equity. Her studies are capacious, with titles such as

“Explaining Progress in Climate Adaptation Planning across 156 U.S. Municipalities.” But they are rooted in careful investigations of local policies—for example, a series of resilience action plans for Boston.

Shi’s focus on policies is unfamiliar to most designers: “In planning, the things we often trade in are papers and books” rather than in projects and precedents. Landscapes are shaped by policies, but planning and design “often happen in the absence of a consideration of policy and other realities that constrain action,” she says. Imagine, for example, a project to build a new park in a low-income neighborhood. It seems good—an amenity for the community. But if a parcel of land becomes a park, it will not be generating property taxes. And who will use the amenity? If designs do not account for policy structures, the market will take over and “do what it does, which is gentrify.” The park may ultimately exacerbate inequities by driving up housing costs. Shi suggests applying the design imaginary to the policy sphere: “a combination of policy and design, rather than the two being separate.”

She began working on issues of equity and justice from a background in environmental management. While working for

AECOM,

Cambridge-based I2UD, and elsewhere, she realized that, in practice, environmental governance is “all about social issues and the rural-urban relationship.” Shi enrolled in a planning doctoral program and was particularly moved by

class taught by Neil Brenner and Diane Davis that gave her a theoretical lens on what was happening and her role in it. She finds this perspective crucial: “Planners, as much as architects, need more reflexive thinking about our roles in our projects and how we embed a concern for justice in our work.”

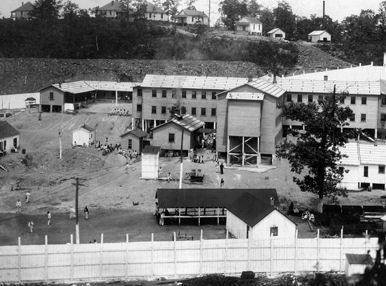

Greenbelt, Maryland, was planned and built by the Resettlement Administration under Rexford Guy Tugwell during the New Deal. [Jason Reblando, from New Deal Utopias]

When asked what planners and designers should do, she warns that devolving decision-making to the community level is not enough.

Community organizations have elevated the importance of justice, but injustices emanate from policy structures that need to be addressed at regional, state, and federal levels. Intent is most important, she says, and “a major issue with the design disciplines is that they don’t teach social justice.” She points to

Billy Fleming’s article in Places, “Design and the Green New Deal,” calling for a role for public landscape architects as one possible direction of reform. But there is no simple fix. For systemic change, Shi says, “We have to transform all of these disciplines.”

One path for change may come from outside the core disciplines of the GSD. David Moreno Mateos, an assistant professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, is a restoration ecologist—which is to say, he is a scientist. Moreno Mateos teaches

“Ecosystem Restoration,” “Climate by Design,” and, this semester,

“Re-Wilding Harvard.” This most recent seminar stems from a radical proposal to return Harvard’s landscape to a condition of wilderness. For now, Harvard has only offered a small plot for experimentation, but what is important for the seminar is not the scale, but the vision. Imagining landscapes without humans is a useful thought experiment for designers who ought to be able to justify the human control their projects require. Moreno Mateos has worked on much larger sites that have been severely degraded by human activity, including Southwest Greenland, where Norse sites have been recovering for more than 650 years. For the Harvard site, Moreno Mateos notes that “Lawn, from a biodiversity perspective, is green cement.” A wild landscape is one that can function on its own, and it is a bold claim that functional wilderness can be re-created even in the middle of Cambridge.

According to Moreno Mateos, part of the process of re-wilding Harvard is to “learn from how people were using the land before European settlement.” Different human groups have had differing power to transform landscapes. The Indigenous peoples of North America had their own impact, causing 95 percent of megafauna on the continent to go extinct over a period of thousands of years. European colonists caused fewer extinctions, but their impact was larger and more temporally concentrated. Human-caused ecological changes are ongoing: with vastly fewer buffalo, for example, forests are now expanding into the Great Plains. The idea is not to assign blame or to return to an imagined idyllic state, Moreno Mateos says, but to see that as one culture displaces another, ways of viewing the land also shift. Now more than ever “we have entirely domesticated landscapes that are not real.”

Moreno Mateos’s work suggests a certain type of environmental justice: “the right of species to live in the place where they used to be.” The first step, he says, is to “understand what an ecosystem actually is,” how it operates, how it responds to human impact, and how it can recover from them. From there, landscape architects may be in positions to use design to help these processes to happen, working with clients on specific sites. And even with wilderness, human involvement is crucial: “You need to listen to people. You need the people who live with an ecosystem to be part of it. Otherwise it’s going to fail,” he explains.

Of all those I interviewed, Kathryn Yusoff offers perhaps the widest lens in generating a picture of the interrelationship of race and landscape. Yusoff holds the unusual title of

Professor of Inhuman Geography at Queen Mary University of London. The cases she brings to the table defy reduction. She gives me an example: “Convict-lease prisons in Alabama were built at the entrance to mines. These prisons were filled with Black men and boys that were literally kidnapped from social space to enter a legal system that systemically punished Blackness, while simultaneously co-opting Black life to corporations as a ‘resource’ for industrialization. Convicts were sent to mine coal and work in the iron ore furnaces. So, there is a very clear connection between what goes up, in terms of the buildings of modernity in the ‘Magic City’ of Birmingham, Alabama and the shares in northern stock exchanges, and who goes down into the underground. This landscape of racial capitalism both met the political ambitions of white supremacy by suppressing the Black vote and materially built the post-plantation urban landscapes through another form of Black subjugation.”

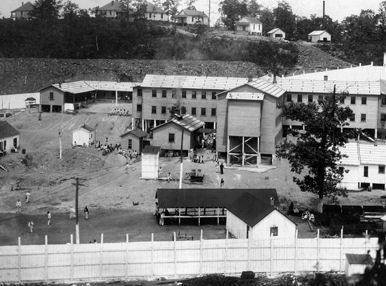

Pratt Company Mining Prison Camp, Alabama (Mining Artifacts).

How to untangle this complex nexus and engage with it as designers? For Yusoff, the first step is to shift what is taken as the object of design. “There is a tendency to assume that the built environment is the primary space of consideration, whereas I would like to disassemble that ‘autonomy’ and have us think with a broader set of relations of the un-architectural or what might be called the subterranean architectures of spatial practices.” If buildings and landscapes present flattering pictures of a simple and tidy social order, a little excavation will uncover a vast network of lives that have been repressed. “What are the racial undergrounds that enable the verticality of the city, its flows, and material connectivity?” she asks.

Yusoff’s work upends key concepts that are in danger of becoming platitudes. In response to the vogue for the Anthropocene (a term that refers to the current geological period, in which humans are having a definite geological impact), Yusoff demands “a billion Black anthropocenes, or none.” The life and perspective of each Black body that has made “the Anthropocene” happen must not be forgotten under the rubric of such a wide and abstract term. “These are the billion life-worlds of Indigenous and Black peoples that colonialism attempted but failed to extinguish,” she says.

Yusoff’s project is big, and its implications are daunting. “This is a transnational and planetary affair and involves confrontations with the histories of settler colonialism, neo-extractivism, and the normative understandings of matter itself.” For designers, aesthetics—how things look—may be the most accessible aspect of Yusoff’s work. She recasts aesthetics as political: “Political aesthetics is a way to think through the aesthetic-as-always-implicated in the construction of sense and sensibility, which is more than a question of feeling. I think about these arrangements of sense as a ‘affectual architectures’” Telling a story, painting a picture, or constructing a landscape is a political act. “We can see any mapping of planetary origins as a world-building praxis, where people and places get framed in certain ways.” One task for social justice, then, is to pay attention to the “strata of peoples that underpin planetary transformation and are pressed closer to its harms.”

However landscapes are understood, seeking justice within them cannot be a simple affair. Engaging with a functioning ecosystem within a cultural landscape and within a democratic society should be viewed as an ongoing process. This engagement involves actively studying—and imagining—what landscapes are, and what they can be. Only then can we begin projecting a better world onto them.

With student advocates’ help, Cambridge set to build more affordable housing

With student advocates’ help, Cambridge set to build more affordable housing

Last month, the city council in Cambridge, Massachusetts, voted to smooth the path for more affordable housing to be built in the city, from which people on low and average incomes are increasingly being squeezed out. The news follows a campaign of more than a year in which students from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design advocated in favor of the “affordable housing overlay.”

Patrick Braga (MUP ’20), who was awarded the

2020 Ferdinand Colloredo-Mansfeld Prize for Superior Achievement in Real Estate Studies in part for his work on the campaign alongside the nonprofit group

A Better Cambridge, says that students had a vital role to play because they are intrinsically tied into the local housing economy. “There will always be students in Cambridge and many of them are taking up apartments that could be going to local people,” says Braga. “If we can get affordable housing built that’s directly geared toward local people, there will be a little less competition at that tier of the housing market.”

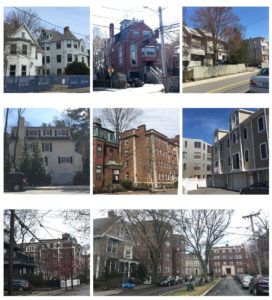

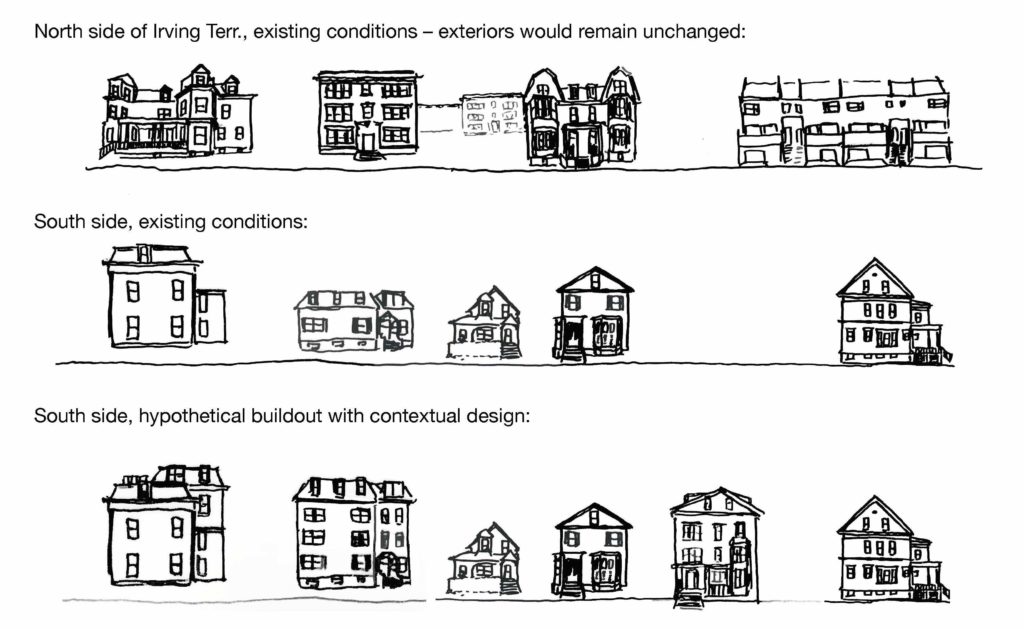

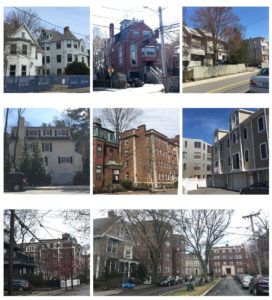

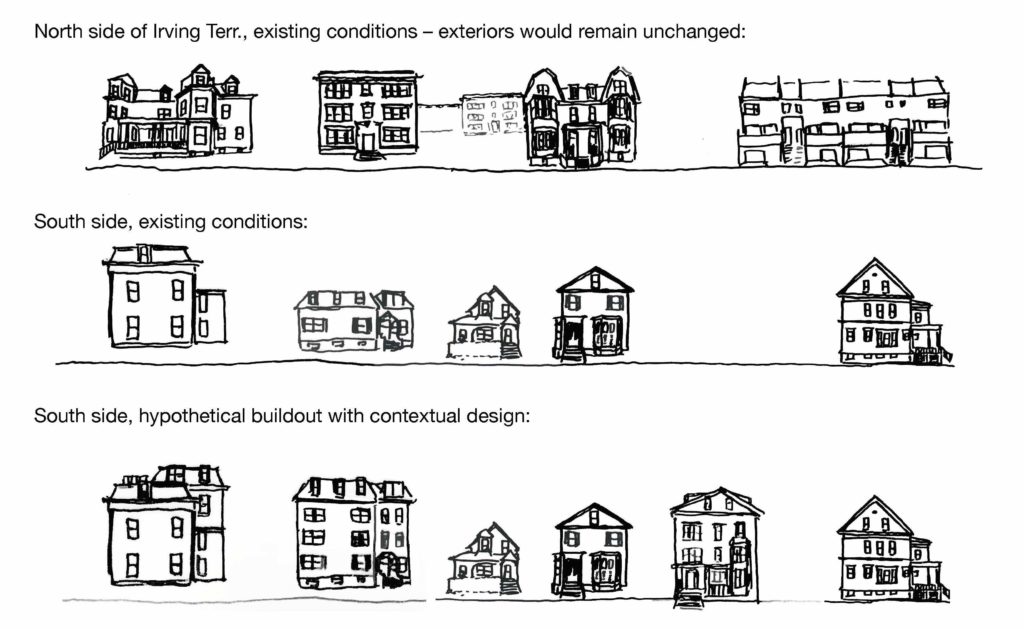

Drawings illustrating the potential and benign impact of the Overlay on Irving Terrace, which happens to be located next to Gund Hall. (Courtesy of Patrick Braga)

The overlay was passed into law by seven of the nine city council members. It means that new developments or conversions in which all units are reserved for households earning below the local median income—at no more than 30% of their earnings—will be automatically allowed, without the need for additional permits.

Examples of four-story buildings already found throughout Cambridge. (Courtesy Patrick Braga.)

As a result, affordable-housing developers will be better placed to compete with private real-estate companies. Previously, the high cost of land and construction and complex rules about the nature of new architecture made it difficult to build anything that would not make a profit. Developers of affordable homes may now find it easier to secure public funding for their proposals, since the release of subsidies often requires them to prove they meet, or have approval to deviate from, zoning requirements. “For developers of affordable housing, having this kind of predictability streamlines the construction process tremendously,” Braga says.

In 2019, 14.8 percent of Cambridge’s housing stock was estimated to be affordable. The hope is that the overlay will allow this number to increase to 16 percent by 2030—a vital increase in a majority renter city. Getting the law passed wasn’t straightforward, Braga says, who worked alongside other GSD students including Thandi Nyambose (MUP ’21), Henna Mahmood (MUP ’21), and Suryani Dewa Ayu (AB ’15 MUP ’20) on the effort. There were concerns from residents that giving the green light to any development that met the basic zoning requirements would mean a flurry of new buildings that clashed with what they saw as the original character of the city—defined by the elegant four- to six-story buildings that were permitted under the height constraints of the 1920s.

“By the 1950s, Cambridge actually had no height limit to its buildings, and there was a lot of a backlash against the architectural changes and the large buildings that suddenly felt out of place with the more human-scale neighborhoods that residents were used to,” Braga explains. “And in the 1970s and 1980s there was increasing recognition of the importance of giving residents of cities and neighborhoods a voice in what future development should look like.”

I think a strength of the GSD is that it made clear to me how important illustrations and visuals are for a policy proposal like this.

Patrick Braga (MUP ’20)

Since then, development in Cambridge has required a lot of negotiation to deviate from zoning codes. “It could take upwards of a year, which meant affordable-housing developers were facing a tremendously high barrier of entry,” Braga says. “Meanwhile, the economy of the Greater Boston region has been booming and jobs are being added faster than housing units, leading to long-time residents and people like firefighters and teachers having increasing difficulty finding homes.”

Last summer, residents and city officials debated the new policy in a meeting that lasted five hours. Passing it meant persuading city council members and reluctant residents, particularly longtime homeowners, that the new rules would not disrupt their neighborhoods. “A lot of people were founding their fears on the notions that there would be high-rises everywhere and old buildings would be demolished, and that their sense of stability would be upturned,” Braga says. “I think a strength of the GSD is that it made clear to me how important illustrations and visuals are for a policy proposal like this.”

As part of the process, the city commissioned a local urban designer to make 3D models to demonstrate that the scale of new buildings would match what already existed. And Braga proposed a rule for how to calculate minimum front setbacks for buildings—by referring to the existing structures on either side—an idea that was eventually incorporated into the final ordinance.

Both a recent graduate and a Cambridge native, advocate Dewa Ayu brings a unique perspective: “As someone who was raised in Cambridge—a proud daughter of street vendors and small business owners—I am excited to see how this can lead to centering the most marginalized voices in our city,” she says.

Toshiko Mori talks designing pandemic-resilient cities for BBC’s The Conversation podcast

Toshiko Mori talks designing pandemic-resilient cities for BBC’s The Conversation podcast

Robert P. Hubbard Professor in the Practice of Architecture

Toshiko Mori was recently a guest on the BBC’s

The Conversation podcast, which features women, united by a common interest or experience, talking about how they are shaping the world around them. Mori’s episode addresses what future cities will look like in a post-COVID-19 world, and includes a conversation with Maliam Mdoko, the first female president of the Malawi Institute of Architects.

Listen now.

Will cities remain resilient in a post-COVID world? BBC asks Jerold Kayden

Will cities remain resilient in a post-COVID world? BBC asks Jerold Kayden

Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design

Jerold Kayden is one of a series of global thought leaders to be

tapped by the BBC to provide insight into what life may be like in a post-COVID-19 world. Addressing how the coronavirus has exposed, and even sometimes accelerated, the flaws in certain areas of our urban environment, Kayden anticipates less activity and reduced tourism for the foreseeable future. At the same time, he believes history offers hope for the future of cities: “There is a raison d’etre for cities not so easily dislodged. The human thirst for live engagement with people and place is not easily quenched. In the past, in crisis after crisis, urban resilience has proved the skeptics wrong.”

Read Kayden’s full answer in the BBC’s

Unknown Questions series.

Excerpt: Cities in Imagination, by David Maddox

Excerpt: Cities in Imagination, by David Maddox

“Five years ago, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s

Just City Lab published

The Just City Essays: 26 Visions of Inclusion, Equity and Opportunity. The questions it posed were deceptively simple: What would a just city look like? And what could be the strategies to get there? These questions were posed to mayors, architects, artists, philanthropists, educators and journalists in 22 cities, who told stories of global injustice and their dreams for reparative and restorative justice in the city.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at

designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

Cities in Imagination

By David Maddox

Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensable leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

But we have to hope that justice hasn’t gone out of style. Because while resilience is the word of the decade, we’ve struggled with just cities for a much longer time. Largely we have come up short.

So this imagining needs a fourth leg. These are the cities of our dreams: resilient, sustainable, livable, just.

Let’s imagine.

We can imagine sustainable cities—ones that can persist in energy, food and ecological balance—that are nevertheless brittle, socially or infrastructurally, to shocks and major perturbations. That is, they are not resilient. Such cities are not truly sustainable, of course—because they will be crushed by major perturbations they’re not in it for the long term—but their lack of sustainability is for reasons beyond the usually definitions of energy and food systems. We can imagine resilient cities—especially cities that are made so through extraordinary and expensive works of grey infrastructure—that are not sustainable from the point of view of energy consumption, food security, economy, or other resources.

We can imagine livable cities that are neither resilient nor sustainable.

And, it is easy to imagine resilient and sustainable cities that are not livable—and so are not truly sustainable.

Easiest of all is to imagine cities of injustice, because they exist all around us. The nature of their injustice may be difficult to solve or even comprehend within our systems of economy and government, but it’s easy to see.

The point is that we must conceive and build our urban areas based on a vision of the future that creates cities that are resilient + sustainable + livable + just. No one of these is sufficient for our dream cities of the future. Yet we often pursue these four elements on independent tracks, with separate government agencies pursuing one or another and NGOs and community organizations devoted to a single track. Of course, many cities around the world don’t really have the resources to make progress in any of the four. Continue reading on designforthejustcity.org…

Announcing the 2021 Wheelwright Prize cycle, fostering new forms of architectural research

Announcing the 2021 Wheelwright Prize cycle, fostering new forms of architectural research

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (Harvard GSD) is pleased to announce the 2021 cycle of the

Wheelwright Prize, an open international competition that awards 100,000 USD to a talented early-career architect to support new forms of architectural research. The 2021 Wheelwright Prize is now accepting applications; the deadline for submissions is Sunday, January 31, 2021. This annual prize is dedicated to fostering expansive, intensive design research that shows potential to make a significant impact on architectural discourse.

The Wheelwright Prize is open to emerging architects practicing anywhere in the world. The primary eligibility requirement is that applicants must have received a degree from a professionally accredited architecture program in the past 15 years. An affiliation to Harvard GSD is not required. Applicants are asked to submit a portfolio and research proposal that includes travel outside the applicant’s home country. In preparing a portfolio, applicants are encouraged to consider the various formats through which architectural research and practice can be expressed, including but not limited to built work, curatorial practice, written output, and other manifestations of research.

The winning architect is expected to dedicate roughly two years of concentrated research related to their proposal, and to present a lecture on their findings at the conclusion of that research. Throughout the research process, Wheelwright Prize jury members and other Harvard GSD faculty are committed to providing regular guidance and peer feedback, in support of the project’s overall growth and development.

In 2013, Harvard GSD

recast the Arthur W. Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship—established in 1935 in memory of Wheelwright, Class of 1887—into its current form. Intended to encourage the study of architecture outside the United States at a time when international travel was difficult, the Fellowship was available only to GSD alumni. Past fellows have included Paul Rudolph, Eliot Noyes, William Wurster, Christopher Tunnard, I. M. Pei, Farès el-Dahdah, Adele Santos, and Linda Pollak.

Harvard GSD

awarded the 2020 Wheelwright Prize to Daniel Fernández Pascual, whose winning proposal

Being Shellfish: The Architecture of Intertidal Cohabitation examines the intertidal zone—coastal territory that is exposed to air at low tide, and covered with seawater at high tide—and its potential to advance architectural knowledge and material futures.

An international jury for the 2021 Wheelwright Prize will be announced in January 2021. Applicants will be judged on the quality of their design work, scholarly accomplishments, originality or persuasiveness of the research proposal, evidence of ability to fulfill the proposed project, and potential for the proposed project to make important and direct contributions to architectural discourse.

Applications are accepted online only, at wheelwrightprize.org; questions may be directed to info @ wheelwrightprize.org Will urban life recover when the pandemic is finally over? Alex Krieger on the fate of the American city after Covid

Will urban life recover when the pandemic is finally over? Alex Krieger on the fate of the American city after Covid

Yes, the pandemic (somewhat understandably) and the protests for justice (sadly) are leading to a partial withdrawal from our cities. Of course, such departures have occurred a number of times over the course of American history. Americans have not needed much encouragement to seek a bit of space between themselves and the “rasping frictions” of big city life.

Prior to the pandemic, American cities were on a roll. Since the turn of the millennium at least, America was actually witnessing an urban revival. Suburbia had lost much of its appeal for the generations that grew up in it, and memories of mid-century urban decay had largely faded. Editorials in urban newspapers announced “the cachet of a city zip code.” Pundits welcomed the arrival of the creative class, and promised an extended era of urban fortune assured by the commitment to city life by the millennial generation. Even some empty nesters were happy to part with lawn mowers in exchange for more convivial urban contexts.

Now in 2020, many people are again falling prey to anxieties about cascading urban problems. We have been reminded that density aids in the spreading of disease. Street protests—even on behalf of just causes—remain somewhat unnerving, especially when they turn to destructive actions. Urban crime rates, after falling for several decades, are once again in the news. More than a few political leaders are stoking fear and divisiveness. In cities, the cost of living, especially for decent housing, seems to increase faster than population gain.

Will there be adjustments as a result of our current crises? Absolutely. Since the Industrial Revolution, Americans have viewed cities as sources of congestion, pollution, crime, undue class competition, the spread of infectious diseases, and too harried a daily life.

Alex KriegerOn health and livelihood within the American city in face of the pandemic

Then comes a new possibility: the untethering of work from the places designated for work. Companies forced to vacate offices due to the pandemic are beginning to question the necessity of ever fully returning to downtown office towers. Employees are assessing the personal and financial benefits of cutting out commutes, having greater daily flexibility, and enjoying more family time while working from home.

Should we succumb to urban anxieties? Or, will cities recover their appeal (unaffordability aside) when the pandemic is conquered? History makes those of us who love cities maintain some optimism. After all, we have become an urban species. Neither devastating fires when cities were made of wood, nor the cholera of Dickens’s London, nor the urban bombardments of World War II, nor the postwar fears of nuclear holocaust, nor even the shock of 9/11 fundamentally altered the pull to urbanize. Neither will COVID-19 over the long term (barring arrivals of COVID-20, 21, etc.). Cities have been, and will remain, in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s memorable phrase, “the human invention par excellence.”

There are advantages to living in a city that are not replicable with digital software. Days filled with Zoom calls and on-line shopping are not an adequate replacement. Today’s global institutions and economies advance with a metropolitan bias—powered by the concentration of innovation-minded talent and entrepreneurial zeal. Some 60 million people have been annually migrating to the world’s cities. They do so, as people have done for centuries, in search of opportunity, economic security, and the promise of a better life. Today’s anxieties will not lead to half of the seven billion inhabitants of earth who currently live in urban regions to all flee to exurbia, or Montana, or the steppes of Russia. (But some rebalancing between immense urban concentrations and smaller and mid-sized cities may be a good thing.)

Will there be adjustments as a result of our current crises? Absolutely. Since the Industrial Revolution—and the accompanying prodigious migrations to urban areas from subsistence farms and across oceans—Americans have viewed cities as sources of congestion, pollution, crime, undue class competition, the spread of infectious diseases, and too harried a daily life. The idea of the garden suburb emerged in reaction to the squalor unleashed by industrial urbanization. And at least since the Transcendentalists, a bucolic setting has been considered ideal for family life.

Now that the possibility of enjoying a hospitable setting while remaining connected to jobs and centers of enterprise has finally become a reality (after having been predicted since the earliest days of the digital revolution), decisions about where to live and commercial investment in city centers will surely be affected. But even as we’re discovering that we can live and work “anywhere,” the inadequacies of life tethered only to home and computer monitors are being revealed. A rebalancing of the domains of work and life will continue, and will affect the planning of cities, especially with regard to density, but to what extent remains uncertain. Predictions about the future rarely come to fruition.

Oscillation between the allure of the city and the allure of living free of city stress has recurred throughout American history. The pandemic will certainly cause some people to seek a haven away from the hustle and bustle, or over anxiety about future pandemics. Still, since global institutions and economies will continue to advance with that metropolitan bias, many more people will continue to partake of all of the cultural riches found in great city centers than will flee for the promise of a safer, if less full, life.

Alex Krieger, Principal, NBBJ. Professor of Urban Design, Harvard University. Author of City on a Hill: Urban Idealism in America From the Puritans to the Present. Pier Paolo Tamburelli on the “hardscrabble, repressed, and perverted” American Gothic psyche

Pier Paolo Tamburelli on the “hardscrabble, repressed, and perverted” American Gothic psyche

In

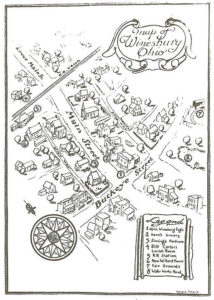

Sherwood Anderson’s collection of short stories, Winesburg, Ohio, the author constructs a portrait of a small town through interrelated tales of its inhabitants’ daily lives. Anderson based the stories on his own experience growing up in Clyde, Ohio. The book, published in 1919, was perceived at the time as hardscrabble, repressed, and perverted: hallmarks of the American Gothic psyche.

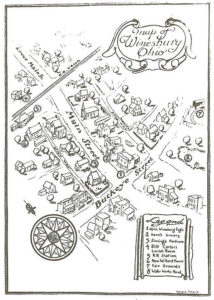

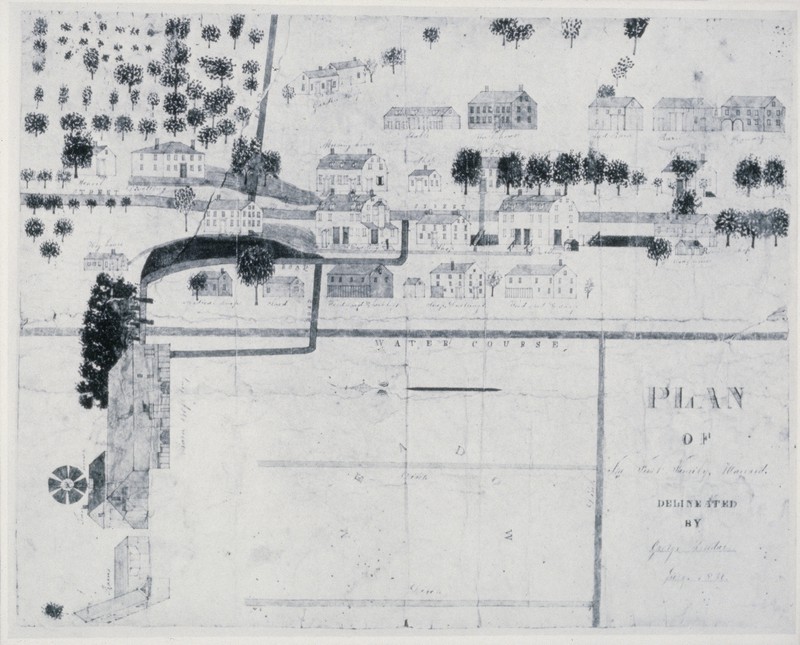

Map of Fictional Wineburg, Ohio from the first edition of Sherwood Anderson’s book “Winesburg, Ohio” (New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1919).

A century later, Winesburg, Ohio, is considered a modern classic. It owes its longevity not to shock value but to how astutely it portrayed a society on the cusp of colossal change. At a time when political upheaval has brought attention to small towns in the American Midwest, architect and Harvard Graduate School of Design professor Pier Paolo Tamburelli took Clyde, Ohio, as a case study for the Department of Architecture studio

“American Gothic, Monuments for Small-Town Life.” Under his supervision, the course created a design hypothesis for a new church in Clyde, exploring the role of architecture in communities that feel they’ve been abandoned and yet recur as a major motif in the American imagination.

“I wanted to ask the students to design a building with a social role, and then I had to accept that in this context the only realistic option was a church,” says Tamburelli, who co-founded Italian architecture office

baukuh. He encouraged students to design a simple architectural object knowing that, in the end, “a building is a building.” But he wanted them to know that a building is also an opportunity for a reflection on what he described as “the supreme indifference to space of the American Protestant tradition” in an essay published in Cult and Territory. Here, Tamburelli speaks of the enduring relevance and intrigue of towns such as Clyde and to what extent context should lead creativity when designing public projects for them.

How did your investigation of the American church come about?

Maybe we can start with a relatively simple, even banal observation: I’m from the countryside in northern Italy, so I’m familiar with provincial places. In a way, they all look the same. And I had been teaching in Chicago prior to Harvard, so I’m also familiar with the Midwest. Of course, the implicit background for the studio is the fact that Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, in part by exploiting a sense of abandonment in a large segment of impoverished white Christians, who used to consider themselves the “silent majority” and just discovered they are no more.

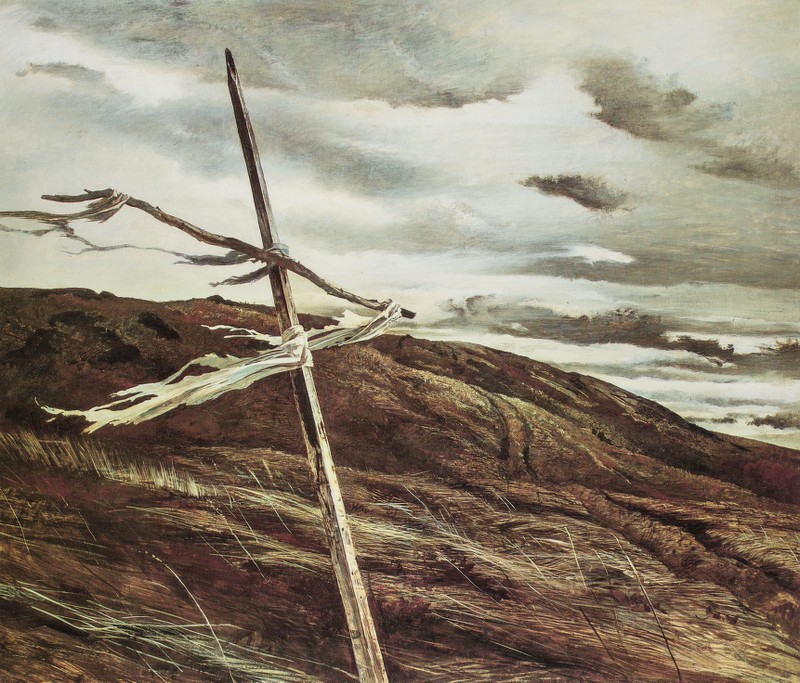

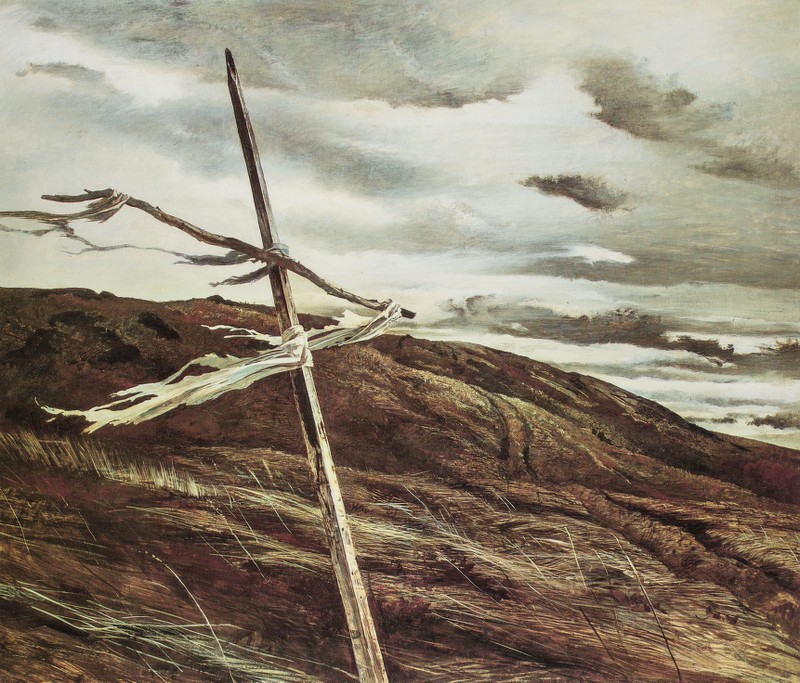

Wyeth, W. (1947). Dodges Ridge.

I thought, “How are these communities actually operating? And how, at least in theory, is it possible to overcome a loss of social fabric in these contexts?” So we went to take a look, and decided to focus on Clyde, Ohio. I read Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. The fictional Winesburg is based on Clyde. Nowadays it has 5,000 inhabitants, more or less, and there’s a gigantic factory producing Whirlpool washing machines. Our studio went to Clyde; we talked to the mayor and saw the different congregations. I think the perception of the people we spoke to was that we were maybe a bit strange, but sincerely interested. We also went to visit some extremely good architecture that has been realized in that region in the last 50 years.

What drew you to the region from an architectural perspective?

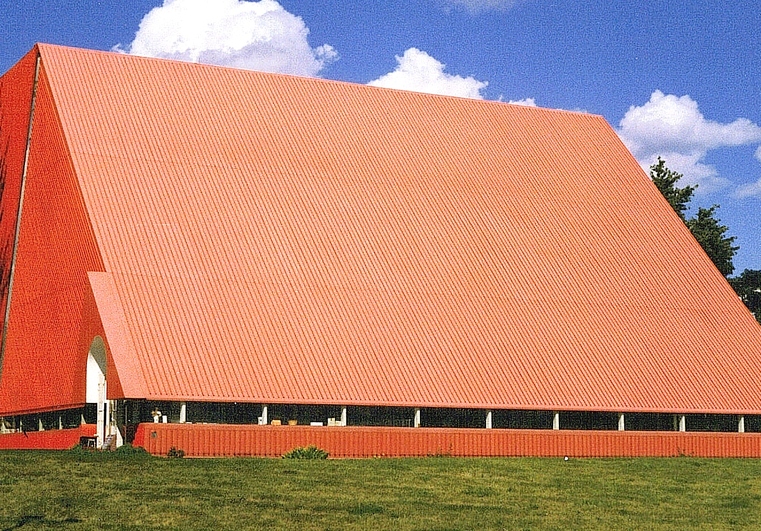

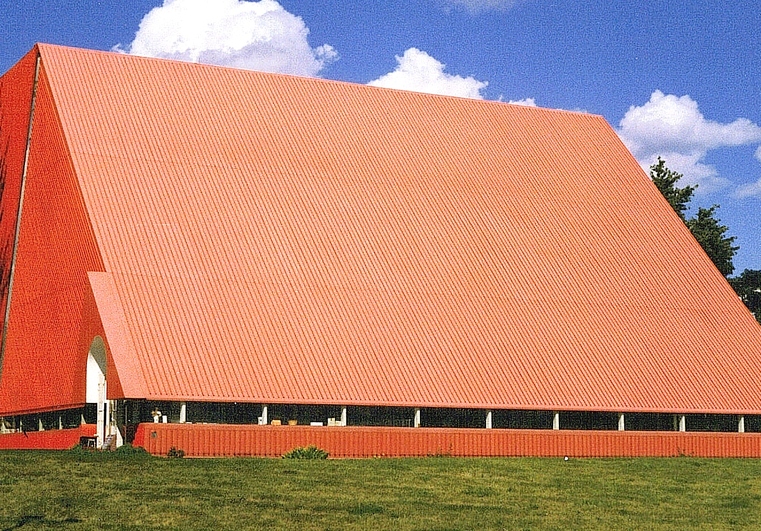

Probably the building that we were the most interested in was the

Calvary Baptist Church by Gunnar Birkerts. It’s an orange hybrid—in between a pyramid and a barn—that somehow landed in the suburbs of Detroit. We met Lawrence T. Foster, an African American pastor who majored in theology at Harvard, who was an excellent guide into understanding the story of that specific congregation—its role in Detroit and so forth. We also went to Birkerts’s Law Library in Ann Arbor, which is amazing. It was a bit of a Gunnar Birkerts celebration tour.

Gunnar Birkerts, Calvary Baptist Church, Detroit. Image by Anthony Lockhart.

I have no idea. I have no theory on churches. I suspect that churches are just buildings like others. They should be convincing as buildings, as architecture. Maybe a church should be capable of suspending the everyday preoccupations—at least for a little bit—and creating a space for something else. Actually, the church as a religious institution was not so important for the studio. I just wanted the students to design a public building in Clyde, and a church was the simplest possible public building in that context. (The only other option was a school, there’s not much else.) I also wanted to avoid a discussion over whether the church should be Catholic or Protestant, or whether it would be better to do a mosque or synagogue because that was not really the scope. I was not so interested in the church as a building, or as a religious experience, but as a place to build a community. I looked for a mainstream Protestant congregation, and we ended up with Methodist.

You were thinking about a disenfranchised, white, Christian minority, as you described it, and you wanted your students to design churches that could rekindle a sense of community…

These things provide background, but they are not a direct input for design. In a way it is not possible to design something like that. It is not possible to rebuild a community by means of architecture. So we moved from the larger investigation of the cultural landscape to the strictly disciplinary. To do that, I asked the students to design the church simply as architecture. The way in which the students would take a position on the wider cultural subjects should pass through the simple fact of designing a church. The studio was an interesting combination: on one side, trying to use architecture as a tool to explore a place and a culture, and on the other side, taking a very strict disciplinary approach to architecture.

From Hands, Concerning Wing Biddlebaum from Sherwood Anderon’s “Winesburg, Ohio” (1919).

In the studio, we discussed a tradition of Europeans coming to America and often being fascinated by these vast, sparsely populated expanses at the center of the country. I tried to be honest in declaring my position as a European who looks at America that way.

I mean, if you’re Italian, the size of the American Plains or the Midwest is incredible. You come from this densely populated country where everything was already settled 2,000 years ago—where every corner has been reshaped, every hill has been polished through ages of adjustments. And then you get to this new landscape where everything is, first of all, so much bigger. The landscape is familiar because it’s the countryside, and also because you saw it in so many American movies while growing up in Italy. And yet there’s something that doesn’t exactly match up. It’s very difficult to describe because it is a sort of a gray area: you are not capable of seeing what is different, so you cannot give it a name. People who came to the US from Europe tried to replicate what they left behind. In Ohio or Iowa, you have these barns that are so-called Dutch, but they really don’t look Dutch.

Lane, L, Old Stevens’ Homestead, Castine (1859).

We wanted to look at these social groups without coming to any final theory. We just tried to design buildings. That’s what we do. But we thought this was a phenomenon that was interesting and that it was, for a while, overlooked. And of course things are complex: the traditional Christian churches are certainly in a crisis. We didn’t know there was a schism brewing between two components of the Methodist Church, for example.

Did the designs of the buildings generated by students respond to the schism?

Sure. I think every student tried to fit the project into that context. Strangely, a lot of American students applied for this class. I think it somehow struck a nerve. Perhaps it was easier for me to do this than for an American teacher. Sometimes a bit of distance, even a bit of ignorance helps you. You don’t get scared by the complexity of the problem.

Preston Scott Cohen’s Post-Shaker studio draws on the austere formal language of Shaker design in proposing a new art colony in Mount Lebanon, NY

Preston Scott Cohen’s Post-Shaker studio draws on the austere formal language of Shaker design in proposing a new art colony in Mount Lebanon, NY

Mount Lebanon, NY has faded. When its last seven inhabitants moved away in 1947 it was already diminished, and now it is an exquisite shadow. For 160 years, 600 Shakers built a community in hundreds of buildings on 6,000 collectively owned acres. Just 10 original buildings remain, and the town has become one of the most endangered historic sites in the world. Last fall, Preston Scott Cohen challenged 12 GSD students in his “

Post-Shaker” studio to propose architectural designs for Mount Lebanon as it enters another time of transformation. With the Shaker Museum’s purchase of a new building for its collections in Chatham, NY, and a successful implementation of an artist-in-residence program in Mount Lebanon, the village will take on new life. Cohen asked his students to envision this revitalization and to “speculate on the establishment of a new art colony” there.

Mount Lebanon Shaker Village, New Lebanon, New York, United States. (n.d.).

The site presents great challenges primarily because to design for Mount Lebanon today, Cohen explains, is to “operate in a very complex middle ground” between an inaccessible past and an indeterminate future. It requires consideration of the strict preservation that is already under way and the inevitable need for adaptation of the site as it accommodates new functions. In this context, Cohen proposes that designers must address the austere formal language of Shaker design, not merely as a set of historical design strategies and elements but as an expression of the Shakers’ unorthodox cultural ideals, which are still deeply relevant as fragments of the village persist.

After their founding in England and subsequent emigration to the United States in 1774, the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing (as the Shakers referred to themselves) established communities in New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Kentucky, Florida, and Indiana. These believers, like many other European religious groups—Puritans, Calvinists, Quakers, Baptists, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Methodists, Catholics, Pietists, Unitarians—settled and thrived in the American colonies. Each had its own idiosyncrasies, but the Shakers were perhaps the most unusual among these groups.

Priest, P., & Kendall, K. (1836). Shaker Village, Church Family Buildings, Harvard, Massachusetts, United States.

Aside from the rapturous dancing, twitching, and gesticulation in the services that distinguished their worship, the most consequential difference between the Shakers and other religious groups lay in their rejection of the typical male dominance over spiritual life. They believed that “Christ’s Second Appearing” manifested in their first leader, Mother Ann Lee, whom they saw as the personification of the feminine part of God’s duality. Accordingly, the duality and balance of the genders became central to Shaker beliefs, and it strongly shaped their way of life and the buildings that accommodated it. Cohen explains, “The Shakers believed in and practiced pacifism, gender and racial equality, and celibacy” and that the precise formal language of design they developed reflected these principles.

Villagers performing Shaker songs and dances at the Shaker Museum Antiques Festival, 1956

To ensure the integrity of their lifestyle and to avoid persecution, the Shakers almost completely removed themselves from the larger society around them. They formed autonomous communities of self-sufficient “holy families” that developed efficient agricultural techniques, productive craft workshops, and a highly refined version of American vernacular architecture. The village of Mount Lebanon was the first of these and acted as a model for other Shaker communities elsewhere. Founded by Lee’s successor, James Whittaker, after her death in 1784, it grew rapidly to include six holy families—Church, Second, South, Center, North, and East. The largest of these, Church Family, included 233 adult members by 1789. The egalitarian and communal nature of Shaker communities eliminated traditional, paternal family structures and other social hierarchies, but maintained strict separation of male and female roles.

Men and women shared leadership of the community, but assumed different responsibilities and produced different things—men built the furniture and women wove the cloth, for example. This played out in all aspects of family life and in the ordering and design of their buildings. They distinctly separated male and female work spaces and sleeping quarters but joined the family together for worship, meals, and other communal functions. Cohen points out that the “binary/non-binary treatment of gender roles” strongly affected more than just the arrangement of spaces in the Shaker village, however. It also controlled the fundamental character of Shaker design, which had “a very particular formal language” that played out at all scales, from the organization of buildings to the precise articulation of the smallest details.

Architectural elements from North Family Dwelling, New Lebanon, New York. ca. 1830-40.

So, when Cohen challenged students to design a new building for an art colony in Mount Lebanon, the central question he asked them to keep in mind was, “What would the Shakers have done?” Answering this question, they could begin to “speak the Shaker language in their own accent.” They would need to do this while navigating between the requirements of preservation and adaptive re-use, and with an understanding that Shaker design resides somewhere between an American rural vernacular and a precise functionalism that, Cohen proposes, is almost “proto-modern.”

The studio began with research about Shaker culture, its differentiation of genders and their labor, its connection to the outside world, its design language. The studio group also visited Mount Lebanon, where they studied the Shakers’ buildings and products. They examined particular sites between the existing buildings that were formerly occupied by North Family. Most of these are typical of Shaker architecture: simple rectangular forms with gabled roofs, white clapboard siding, symmetrically arranged windows, and gender-specific doorways, work spaces, and circulation. However, prominent among these buildings, the stabilized ruin of an immense stone dairy barn built in 1859 is unusual and inconsistent with typical Shaker design, complicating visitors’ conception of Shaker architecture. This added to the complexity of the students’ task of designing to fit into a Shaker context.

Kendall, K. (1835). Shaker Village, Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, United States.

Throughout the studio, Cohen explains, it was necessary for students to “find a way to work on cultural connections.” They had to develop a clear understanding of the Shakers’ formal language as a manifestation of the community’s unorthodox values, while also finding “the motivations inherent to [their] own intuitions, ideas and plans,” which are naturally reflective of contemporary culture. Design work started with experiments in symmetry. In the studio brief, Cohen emphasized that the Shakers’ formal language involved complex symmetries.These symmetries, which had both practical and divine overtones, became the springboard for the students’ rich design investigations. Cohen challenged them to play with symmetry: to develop, for example, “unusual dual symmetry” at the scale of rooms; “alterable symmetries” using movable walls and furniture; complex volumetric symmetries in stairs and circulation systems; and “oddly symmetrical” arrangements of building masses using “typical features of Shaker traditional buildings (gables, dormers, typical windows and doors…).” The key in these exercises was to explore new accents of Shaker architecture that were “plausibly Shaker in sensibility.”

While much of the inspiration for these experiments in architectural symmetry derived from traditional Shaker design, Cohen emphasizes that it also developed out of his own long-standing interest in complex architectural symmetries, dating back at least as far as his 2001 book, Contested Symmetries and Other Predicaments in Architecture, which describes methods of creating complex designs using geometrical operations on familiar forms. The students’ final designs for Mount Lebanon in the “Post-Shaker” studio demonstrate how effectively the precise architectural language of Shaker architecture lends itself to the geometrical operations Cohen and his students explored. Each project seems simultaneously familiar and strange. Simple, gabled volumes shift and overlap; precise moldings wrap around doors and windows into the deep space of interpenetrating rooms; volumes twist with the terrain and struggle to maintain balance; rectangular doors and windows reflect across multiple oblique axes; gender-specific stairs and hallways wrap around each other only to join at unexpected moments.

While the Utopian Shaker experience of Mount Lebanon has long faded, its precise architectural language still speaks loudly today. The “Post-Shakers” in Preston Scott Cohen’s GSD studio found and voiced 12 new inflections of that powerful idiom.

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays

These essays were meant as a provocation, a call to action. Now, during these times of dissonance, unrest, and uncertainty, their contents have become ever more important. For the next 26 weeks [starting June 15, 2020], the GSD and the Just City Lab will republish one essay a week here and at designforthejustcity.org. We hope they may continue conversations of our shared responsibility for the just city.

We believe design can repair injustice. We believe design must restore justice, especially that produced by its own hand. We believe in justice for Black Americans. We believe in justice for all marginalized people. We believe in a Just City.”

—Toni L. Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning, founder of the Just City Lab, and editor of The Just City Essays