Urban Design as a Development Strategy: The Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture Campus

by MASS

The 15th Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design has been awarded to the Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture (RICA) campus in Bugesera, Rwanda, by MASS. In addition to detailing RICA’s innovations in sustainable design and its potential to transform agriculture in Africa, this exhibition highlights the process of the campus development as well as the project team’s commitment to experimentation within the field of urban design.

RICA’s master plan, led by MASS, includes more than 20,000 square meters of buildings and 1400 hectares of landscape in rural Rwanda. The project encompasses housing, academic spaces, barn storage, processing space, stormwater systems, human and animal waste management systems, and off-grid energy infrastructure. RICA harnesses symbiotic ecological and agricultural relationships, and regenerative principles to achieve greater crop yields, increased biodiversity, utilized waste streams, healthier soils, and cleaner water.

The Green Prize recognizes that RICA is more than a campus. The final design developed through a constant negotiation between city officials, motivated designers, and mobilized citizens. This process demonstrates how architecture and agriculture, land and community, city and nature, can be reconnected in ways that are environmentally sound, structurally rigorous, and socially meaningful.

RICA is the first project in the African continent to be awarded the Green Prize. It is also unique in this roster of Prize recipients for both its agro-based rural context, and its function as a space for learning. Fusing agricultural, ecological, and pedagogical design, RICA embodies a new paradigm that negotiates boundaries of urban/rural, infrastructure/landscape, and learning/living. By suggesting that the discipline’s principles can and should extend to rural development, ecological stewardship, and spatial learning, RICA projects a new frontier for urban design’s global relevance.

– Joan Busquets

Veronica Rudge Green Prize Jury Chair and Martin Bucksbaum Professor in Practice of Urban Planning and Design

Urban Natures: A Technological and Political History 1600–2030

URBAN NATURES:

A TECHNOLOGICAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY

For more than three centuries, we have pondered the role of nature in urban development. From the first gardens that were opened to the public in the late 17th century, such as the Tuileries Gardens in Paris or Hyde Park in London, to our contemporary urban forests, the approaches toward nature taken by architects, engineers, landscape architects, and their clients are inseparable from technical challenges as well as political and social concerns.

Technical aspects range from preparing ground and managing water to organizing the cohabitation of natural elements and human beings. These tasks have become increasingly urgent with the advent of climate change and the ensuing need to prevent disastrous effects, such as urban heat islands rendering swaths of urbanized areas unlivable.

Since the Enlightenment, nature’s presence has been inextricably linked to hygienic concerns as well as the desire to help people live together in a society threatened by economic inequalities and social divisions. This ambition runs through the landscaping policies that informed the transformation of Paris under Baron Haussmann and the creation of New York City’s Central Park. From the 18th century to the present day, the history of nature in the city has thus gone hand in hand with successive visions of the workings of society.

This history reveals a diversity of aspirations, projects, and practices that would be hard to reduce to one leitmotif: hence, the use of the plural in the title Urban Natures. This exhibition enables visitors to discover how the importance of urban natures has expanded over the centuries. It has reached a new level with our current environmental crisis, the solution to which lies in forging new links between humans and all the non-human entities on which our survival depends: from soil to water resources and from vegetation to animal populations. The spread of community gardens and urban agriculture reflects this growth of awareness.

The study of urban natures measures how far we have come since the first public gardens were created and asks us to envision the future of our cities in innovative ways.

Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology, Director of Doctoral Programs & Director of the PhD Program

Collaboration with Professor Erika Naginski, Robert P. Hubbard Professor of Architectural History

Commencement Exhibition 2025

This begets that.

This is a group of students who have spent years together, many first on Zoom, and then, happily, all here at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD). That is the world out there. This is the always changing route our students have taken to get here. That is the compass each of them will set on their way forward. This is the kaleidoscope of our students’ potential. That is the change each of them will put in motion to change the world. We can’t wait to see their impact.

That begets this.

The GSD’s 2025 Commencement Exhibition, presented in the Druker Design Gallery and Frances Loeb Library, includes work from all of this year’s graduating students. Please take it all in and wish them well. We are sad to see them go, but our world needs their smarts.

—Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Harvard University Graduate School of Design: Studios & Seminars, Spring 2025

Envisioning Cluny:

Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2025

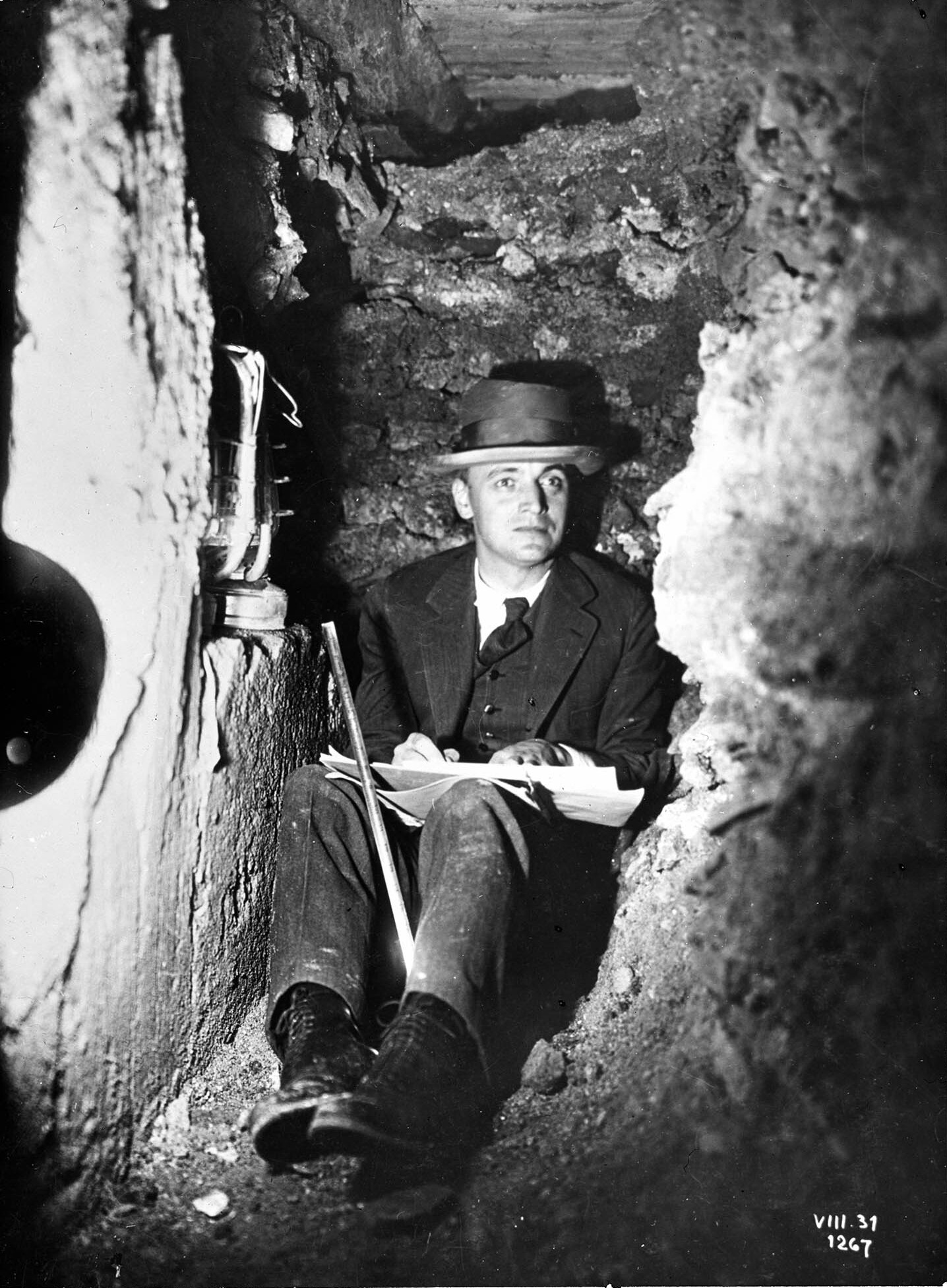

This exhibition celebrates the study of medieval architecture at Harvard University. While medieval buildings have been continuously studied, the technologies of their visualization, knowledge about them, and the purposes to which this knowledge was and is applied have evolved constantly. The representational means by which architecture can be studied, taught, and envisioned have progressed from photographs, drawings, and casts to digital images and animations. This tradition, represented by the remarkable holdings used for teaching and research of Harvard University repositories, is illustrated by the works on view. A connective thread of the narrative is Kenneth Conant (1894–1984) who, having received his undergraduate and graduate degrees from Harvard University, taught architectural history here from 1920 to 1954.

The four sections of the show begin with Conant’s architectural training and formation as a scholar, focusing on the late nineteenth-century adoption of the new medium of photography, important both for medievalizing architectural design and innovative art historical method. The second section features Conant’s work at the third abbey church of the Benedictine monastery at Cluny, built in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and almost entirely destroyed following the French Revolution. Believing the church to have been one of the most important and beautiful creations of the Middle Ages, Conant envisioned the original appearance of Cluny III, as it is known today, by embodying meticulously measured remains in compelling graphics vivified by his extraordinary imagination. The exhibition’s third section centers on the eight plaster casts of capitals from Cluny III that Conant commissioned in 1929 and displayed in the Fogg Art Museum until 1936. Plaster casts of famous works of art were the means by which American architects learned the history of their craft, acquired a vocabulary of historical tropes to apply in their own work, and formed their taste by gaining an appreciation for the “best” works. By the 1920s, the canon of artifacts worthy of such study had been extended to cultures previously excluded or ignored, such as the pre-Gothic Middle Ages in Germany and France. The Cluny capital casts exemplify this trend. At this same time, casts became less valued than study of original works: today few of the many casts once on view in the Fogg Art Museum and Robinson Hall, Harvard’s architecture school until 1972, can be seen on campus.

The narrative concludes with recently created 3D digital models of the Cluny capital casts. These high-resolution, photorealistic representations of real-world objects allow students and scholars to engage with surrogates in new ways that suggest previously unimagined possibilities for future scholarship.

Exhibition Curator

Christine Smith, Robert C. and Marion K. Weinberg Professor of Architectural History

CHANGING CLIMATES: Projects and Research by Bas Smets

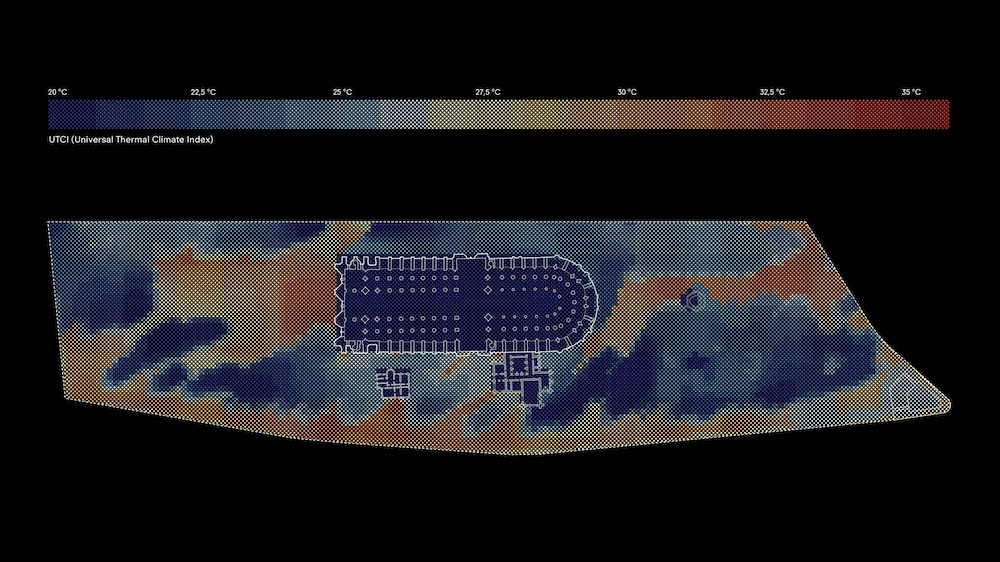

A city can be understood as an aggregation of artificial climates. Buildings alter wind patterns and modulate sunlight exposure, while streetscapes modify runoff and affect soil permeability. Within this artificial environment, landscape architects can create microclimates with intention, treating the city as a living laboratory. Informed by the detailed study of how plants and other organisms transform their natural environments over time, landscape architects introduce vegetation into the urban fabric as an agent of change. The resulting new microclimates make the built environment more resilient in the face of the steadily growing crisis of the macroclimate.

Just as natural ecosystems alter the land on which they develop, urban ecologies have the capacity to reshape the environment in powerful ways. Living matter, as Vladimir Vernadsky observed, can act as a geological force. At the thin interface between an uncertain climate above and a malleable geology below, urban ecologies are critical zones of life. Maintained and reproduced carefully, these ecologies can be resources for a sustainable future.

This exhibition of projects and research by Bas Smets illustrates how new urban ecologies can be conceived and constructed. A selection of three major projects from Smets’s international practice demonstrates how landscape architecture can respond to different challenges of the climate crises: from the enhancement of outdoor comfort and reduction of the perceived temperature around Notre-Dame in Paris, to the transformation of a sterile wasteland in Arles into a self-sustaining ecology, to the creation of an embankment park that mitigates the rise of water levels in Antwerp. What these projects hold in common is a commitment to solution-based design grounded in scientific research.

Appointed as a Professor in Practice at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2023, Smets is conducting a five-year research program into the climatic resilience of cities with his studio, “Biospheric Urbanism.” The students’ projects for two case studies, on New York City and Paris, are exhibited as an illustration of his methodology. The case studies and the projects demonstrate how any given city offers the opportunity to rethink the built environment as an urban ecology that produces microclimates.

Bas Smets is the founder and principal of Bureau Bas Smets (Brussels & Paris)

He is Professor in Practice at the Graduate School of Design of Harvard University

Exhibition Credits

This exhibition is made possible by the Daniel Urban Kiley Exhibition Fund in Landscape Architecture

Exhibition Curation and Design: Bas Smets, Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture

Curatorial and Design Assistants: Dan Borelli, GSD Director of Exhibitions; David Zimmerman-Stuart, GSD Exhibitions Coordinator; Romina Totaro, Bureau Bas Smets

Models: Bureau Bas Smets, Small Hands

Videos: Bureau Bas Smets (Jacopo Fochi, Romina Totaro)

Photos: Iwan Baan, Rémi Bénali, Michiel De Cleene

Installation Team: Ray Coffey, Jeff Czekaj, Anita Kan, Sarah Lubin, Jesus Matheus, Joanna Vouriotis

Harvard Graduate School of Design: Sarah Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture; Gary R. Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture & Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture; Ken Stewart, Associate Dean of Communications and Public Programs

GSD Communications and Public Programs: William Smith, Editorial Director; Rachel May, Assistant Director, Editorial; A. Krista Sykes, Assistant Director, Editorial; Maggie Janik, Senior Multimedia Producer; Kyra Davies, Assistant Director of Digital Media

Sarah Rafson, Associate Director of Public Programs; Raquel Rivera, Public Programs Coordinator; Matt Smith, Assistant Director, Multimedia Production

Graphic Design: Chad Kloepfer, Art Director; Willis Kingery, Designer

“Biospheric Urbanism: New York City”: Jiyoung Baek, Li Jin, Tristan Kamata, Julia Li, Angelica Oteiza, Chanwoo Park, Austin Sun (TA), Parama Suteja, Jessie Xiang, Weiran Yin, Sunjae Yu, Zheming Zhang

“Biospheric Urbanism: Paris”: Rocio Alonso, Gina Bernotsky, Leila Breen, Duke Dunham, Emilie Dunnenberger, Roxanne Gardner, Emily Hayes (TA), Slide Kelly, Crane Sarris, Sarah Segura, Jie Zheng, Geli Zhou

These studios were generously supported by the LUMA Foundation, Landscape and Ecology Research Series Fund

Architecture as an Instruction-Based Art

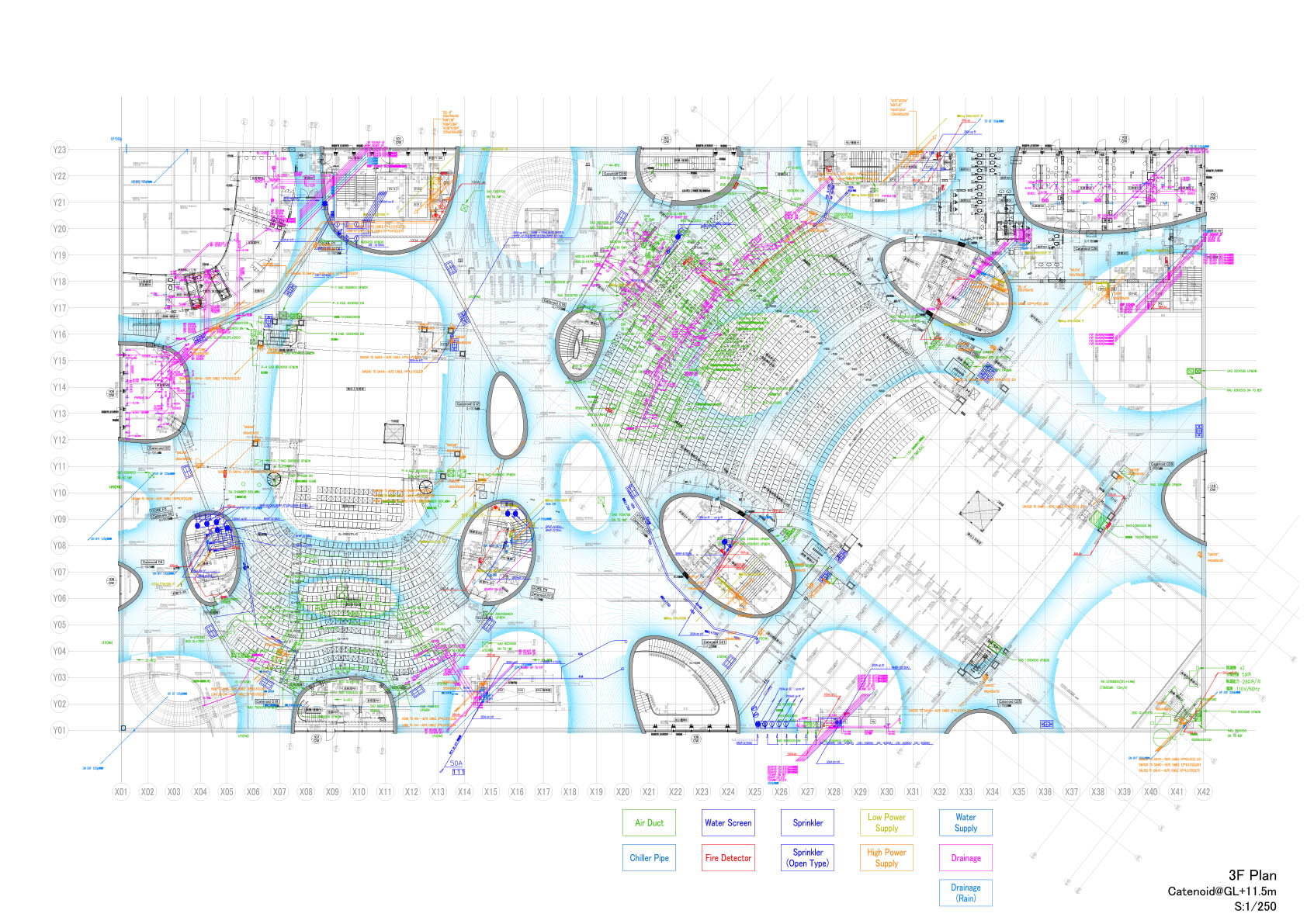

The architecture of a building is a product of assemblage, or the way physical elements—forms, materials, textures, colors—are combined to create enclosed and open spaces that have a distinctive presence. In the process of combining these elements, the architect must also address a range of separate and often irreconcilable challenges and constraints, such as security needs, rights of light, sustainability engineering, and regulations for fire, health, and safety. Such constraints are an essential part of designing a building that will exist in a place and time and impact humans and nature. By defining priorities and making choices regarding what is fixed or moveable, traversable or impassable, audible or inaudible, visible or invisible, touchable or untouchable, closed or open, transparent or opaque, and the colors, geometries, and structures that are present, architects are capable of generating unpredictable assemblages that define people’s everyday experience in unique ways.

Unlike the painter or the sculptor, the architect’s final act results not in a completed work of art but in a set of instructions that enable the intended assemblage to be realized. In this sense, an architect’s work is closer to that of a conceptual artist. The architect’s instructions, which incorporate the input of engineers and numerous other experts, are recorded by a team of collaborators. These instructions are then implemented on a site that is usually exposed to the elements and the dynamics of time, often several years, as specialist builders, roofers, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, and decorators complete the building. Meanwhile, however, architects remain both legally and morally accountable for what follows from their instructions.

Today, architectural instructions appear as different layers of a complex, computer-aided design drawing, which can be described as a construction coordination drawing. Such drawings bring together the elements of a building that are visual and non-visual, physical and non-physical: pipes, studs, and conduits are indicated along with doors, windows, and stairs, as well as components related to lighting, sound, and heating. Architects produce construction coordination drawings to determine how a building should coalesce as a whole, while using them as point of reference when communicating with engineers and other consultants that they work with during the design process.

Construction coordination drawings are different from the sketches, perspectives, diagrams, maquettes, and other images that architects use to convey their ideas for a particular building to its patrons and users. They are also different from straightforward construction drawings that are extracted from the construction coordination drawings, with each drawing conveying a partial description of the building to the contractor or a subcontractor. Therefore, for architects, construction coordination drawings are not an aid to presentation or representation, but rather a tool—a way of working things out. They are the drawings that enable the architect to make decisions regarding the part each element will play, not only in the underlying anatomy of a building, but in the way it is experienced.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design: Studios & Seminars, Spring 2024

Harvard University Graduate School of Design: Studios & Seminars, Spring 2023

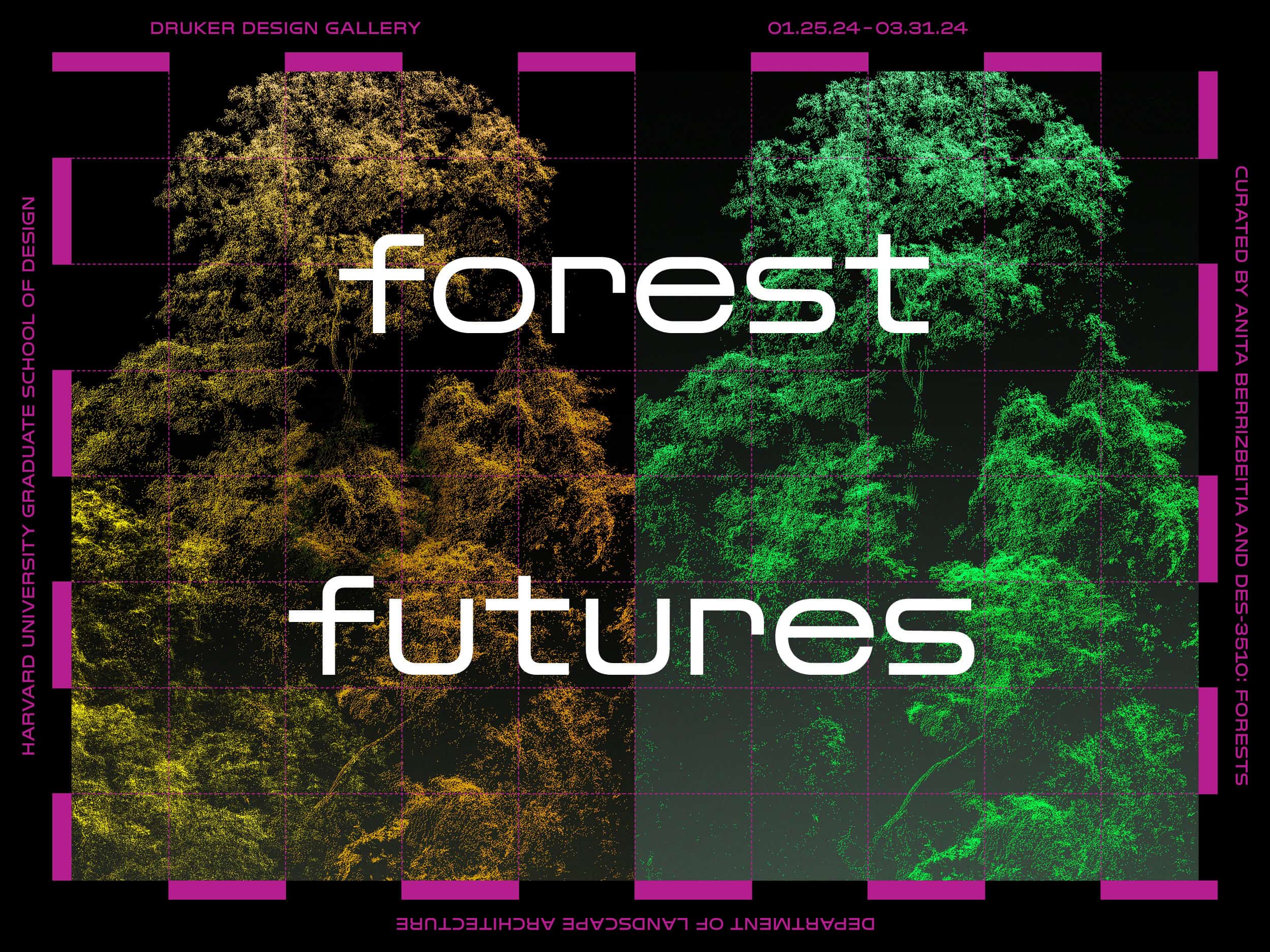

FOREST FUTURES

FOREST FUTURES explores the intertwined history of forests and humanity, critically examining the past and the present to emphasize our profound connection with these vital habitats. A glance at the ungraspable timeline of forest evolution, 350 million years, reveals an alarming fact: a millennium of human activity—a blink of an eye in geological time—has threatened the equilibrium of these life-sustaining ecosystems.

Through the collective efforts of scholars, scientists, designers, artists, policymakers, and communities to restore and conserve the biodiversity that remains, today’s forests have become designed environments. Yet, it is essential to recognize that silvicultural practices and other forms of forest management entail the construction of symbiotic relationships with living beings while enabling nature’s own processes to unfold freely. Trees—indeed, all flora—are wildlife.

FOREST FUTURES celebrates nature’s ineffable essence. By urging a sensorial connection beyond observation, the exhibition underscores the limits of logic alone to fathom the natural world’s complexity. Instinct over reason offers a further lens to envision potential narratives within the still-unknown realm of forests. The paradox lies in merging design—fundamentally a reasoned and measured endeavor—with raw nature. This juxtaposition produces the challenge—at times the overwhelming sensation—of learning the vast science of forests while at the same time staying deeply attuned to the powerful experiential dimension they offer.

FOREST FUTURES’ curatorial approach reflects the diverse storylines explored in the seminar FORESTS: History and Future Narratives at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. As forests capture the attention of multiple disciplines, each exhibition section incorporates historical, technical, artistic, and scientific perspectives. In addition, forests require many forms of labor. Beyond the actual planting—now undertaken by both human hands and robots—advocates, activists, citizen foresters, and volunteers contribute enormous efforts to making healthy forests a reality. Urban forests, in particular, become tangible expressions of the dialogue between design and the natural world, offering opportunities for climate change adaptation and environmental justice. Together, these various perspectives converge on the larger ambition of more equitable societies, each thriving under the vast canopies of the earth’s munificent forests.

CONTRIBUTORS Ajuntament de Barcelona, Barcelona City Council, Arquitectura Agronomía, Francesca Benedetto, Silvia Benedito, Anita Berrizbeitia, Bureau Bas Smets, Buro Happold, Luis Callejas/LCLA Office, Danielle Choi, Cities4Forests Program, Kira Clingen, DPA Picture Alliance, John Dialesandro/LA Times, Gareth Doherty, Gerber Architekten, Ed Eigen, Lisa Haber-Thompson, Mark Heller, Henning Larsen, Howard Center for Investigate Journalism and Capital News Service, Mariona Gil, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Stanley Greenberg, Junya Ishigami + Associates, Àlex Losada, Magnolia Tree Earth Center, Mosbach Paysagistes, NASA Earth Observatory, Omrania, Curro Palacios, Pablo Pérez Ramos, Reed Hilderbrand, RI India, STOSS Landscape Urbanism, SETEC Engineering, Studio in Site, SWA Group, Inc., Taller Capital Loreta Castro Reguera, Daniel Vargas, WRI India, WRI Mexico, and Zion Breen Richardson Associates The exhibition also includes 28 black and white photographs by New York artist Stanley Greenberg. Most of these (25) are from his book Olmsted Trees (2022), which documents trees planted in the 19th century for Olmsted’s original park designs around the country, including many in Boston. Additional photographs, entitled Coronavirus Shelters, are of rustic structures built by local residents in Prospect Park at the beginning of the pandemic, created to provide play space when public playgrounds had been closed. CREDITSExhibition Curation and Design Anita Berrizbeitia, Professor of Landscape Architecture

Students: Natalie Boverman MArch I/ MUP ‘25, Hiteshree Das MDes ‘24, Emilie Dunnenberger MLA I ‘24, Rinka Gao MLA I ‘24, Laura-India Garinois MIT SMArchS AD ’24, Andres Harvey MDes ‘24, Miguel Lantigua Inoa MArch II / MLA I AP ‘24, Yuhan Ji MLA II ‘24, Amelia Jones MDes ‘25, Alexandra Kupi MArch II ‘25, Florencia Lima MLA I ‘24, Patrick Margain MLA II ‘25, Gracie Meek MLA I AP ‘24, Emily Menard MLA II ‘24, Rosita Palladino MDes ‘24, Ya Qin MDes ‘25, Katie Wu MLA II ‘24, Elaine Zmuda MLA I AP ‘24.

Research Assistants Aura Phongsirivech MDes ’23, Manuel Bouzas MDes ‘24

Curatorial and Design Assistant Manuel Bouzas MDes ‘24

Dan Borelli, Director of Exhibitions David Zimmerman-Stuart, Exhibitions Coordinator

Installation Team Ray Coffey, Jeff Czekaj, Anita Kan, Sarah Lubin, Jesus Matheus, Joanna Vouriotis, Miguel Lantigua Inoa MArch II / MLA I AP ‘24, Emile Dunnenberger MLA I ‘24, Ya Qin MDes ‘25, and Katie Wu MLA II ‘24

Fabrication Lab Rachel Vroman, Iris Ayala, Burton LeGeyt, Marco Martins, Steve Spodaryck, Harris Rosenblum

GSD Communications and Public Programs William Smith, Editorial Director Joshua Machat, Assistant Director Communications and Public Affairs Kyra Davies, Assistant Director of Digital Media Chad Kloepfer, Art Director Paige Johnston, Associate Director of Public Programs Raquel Rivera, Public Programs Coordinator Matt Smith, Assistant Director, Multimedia Production

Graphic Design Chad Kloepfer and Willis Kingery