An Island in Flux: Envisioning a more resilient Nantucket

Nantucket offers a vivid illustration of the principle of flux, the idea that everything is in a constant state of becoming. There is a powerfully optimistic sense to this ancient Greek concept: on one hand, steady change begets stability—think of a river or an organism, which is never quite the same from one moment to the next, yet it resolutely maintains its identity—and on the other, “becoming” suggests possibility, improvement, and innovation. Lately, we have become accustomed to viewing change with trepidation: climate change, especially, offers fearsome potential for catastrophe. Warmer temperatures and rising oceans will alter Nantucket, possibly inundating its beaches, its historic town center, and other low-lying areas across the island.

A recent survey of Nantucketers revealed that over 70 percent are “very worried” about climate change. However, the Envision Resilience Nantucket Challenge organized by ReMain Nantucket calls for a sense of confidence in the face of change. It “seeks to inspire the community to imagine a future that is adaptive in the face of sea level rise.” Over the last year, ReMain Nantucket has brought together island residents, scientists, business leaders, artists, and preservationists to advise graduate students and faculty from five different US design programs, including a group from the Harvard GSD led by Professor Chris Reed, as they considered the possibilities for long-term change on Nantucket.

Nantucket took shape through the unhurried dynamism of earth’s geological transformations. Twenty-five thousand years ago, the slowly advancing Laurentide ice sheet pushed huge piles of soil and gravel southward, forming irregular glacial moraines south of Cape Cod. The ice retreated, sea levels rose, and erosion beat down the low hills to form Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands. The earliest settlers on Nantucket walked there from the mainland before the Atlantic gradually surged up around it. Some 10,000 years before Greek philosopher Heracleitus first wrote about the concept of flux, the Wampanoag people benefited from change on the island, taking advantage of its seasonal abundance of food. They fished on the windswept shore during the summer and retreated to more protected inland areas to hunt and harvest cranberries in the winter.

European settlers on Nantucket from the 1640s on carried with them a very different understanding of change and land tenure, fixing property boundaries and building more permanent settlements. Although their fortified harbors, sturdy wooden buildings, and well-established infrastructure offered a degree of stability over the last four centuries, natural flows of water, wind, and time have continually enforced the inevitability of change. The island’s first harbor silted up in the late 18th century, requiring the main town to move two miles to a new harbor. A hundred years of whaling enriched the island, but a devastating whale oil fire, another silted harbor, and the distant civil war sent Nantucket into decline. The whalers and other settlers drifted away, although a diminishing fishing industry persisted. Beginning in the 1950s, tourism shifted the island’s economy again, bringing wealthy property owners and visitors and as well as a diverse population of seasonal and full-time service workers.

Global climate change will affect this current version of Nantucket, but the crucial question is whether sea level rise, altered ocean currents, and unfamiliar weather patterns will bring catastrophe or a new becoming for the island. Reed’s spring semester Landscape Architecture studio, “Away. . . Offshore. . . Adrift. . . Shifting Landscapes, Unstable Futures,” delved deeply into this question. Although it carefully addressed the Envision Resilience Nantucket Challenge, the studio considered the consequences and possibilities of change even more broadly, both in the context of the island, and with a view toward other maritime localities that must also respond to climate change. Reed and his 10 students examined the natural and human drivers of change, in order to understand their entanglements and their mutually reinforcing influences on the island.

In the initial research portion of the studio, “Migrations,” Reed proposed that “climate change and human practices are already having significant impacts on the island, eroding bluffs and collapsing houses, flooding critical infrastructures and streets around downtown and the port, impacting the quality of the natural environment and its ability to sustain habitat and ecological life.” To understand these circumstances more fully, students undertook research in five different areas—earth, water flows, ecologies, people, and land tenure—“within a broader frame of glacial, hydrologic, ecological, and social change over longer periods of time.”

Part of the goal of this first phase, Reed explains, was to avoid merely responding to the crisis at hand—to “the set of now conditions”—so they could account for “the bigger forces that are in play.” Using software to model the flows of water, for example, the students were able to understand present-day mechanisms of erosion and sedimentation within the much longer processes of constant change that have shaped the island from the beginning. They could then speculate on how these flows might continue to alter Nantucket’s shorelines. In particular, Reed points out, students could envision how human efforts, such as the creation of groins, jetties, and artificial islands, or the dredging of harbors, have contributed to natural geological alterations of the island. Modeling provided crucial insights into the problems these devices have caused, but also showed how they might be used creatively to help mitigate or even capitalize on long-term effects of climate change.

Research into social changes on the island yielded other insights, recalling, for example, the “light touch” of Indigenous modes of seasonal land use, in contrast to European settlers’ more fixed approaches to settlement on the island. The students investigating people and land tenure on Nantucket also uncovered the diverse stories of an island disconnected in crucial ways from mainland culture—of the Wampanoag settlers—“People of the First Light,” of enslaved people who had escaped their oppressors and found refuge on the island, of generations of prominent Black landowners and whalers who prospered there, and more recently of a large number of people from all over the world who provide seasonal labor.

In phase two of the studio, “Shifting Grounds,” students continued their research with what Reed calls “performative speculations.” These exercises “introduce a physical design component,” Reed explains, and get the students “to deal with materials, physical things and physical forms within a constantly changing and dynamic environment.” Digital simulations in this phase of the studio helped students look at “the physical and the temporal, and the mutual effects between them, so that they are designing with these forces in mind.” They investigated ways, for example, that installation of fences or piles on a vulnerable shoreline might help control beach erosion and encourage dune deposition, or how chains, nets, and other small structures anchored in shallow tidal areas would channel flows of water and sediment to make shore areas more productive for sea life, or how houses might be anchored against the attrition of coastal bluffs.

During the final phase of the studio, “Provisional (Re-)occupations,” the students carried this research into designs for specific sites on the island. In focusing on the vulnerable areas identified by Envision Nantucket—Brant Point, downtown, and Washington street—students developed extensive long-term proposals that could take advantage of sea level rise and shifts in tidal currents to improve habitats and accommodate evolving public interests. But Reed explains that he wanted these proposals “to go beyond the brief that Envision had given us, which was very much focused on the inner harbor and the downtown,” in order to address more comprehensive climatic and social issues that affect the whole island. So students also proposed long-term protections for and reconfiguration of other important places on the island—the collapsing bluffs on the North Shore and the barrier beach of Coatue peninsula.

The benefit of going beyond the brief in their proposals, Reed argues, was that “because we stepped so far back to look at some of the formational processes in a bigger geography [the students] were able to say ‘we can actually address a whole bunch of potentially bigger problems by acting out here, than by acting locally.’” The resulting designs proposed sometimes subtle, sometimes dramatic adjustments to the island’s shorelines that would allow Nantucket to evolve productively while sustaining the fundamental identities of the island and its communities.

Although climate change is a developing crisis—a widespread disaster of our own making—this studio extended from a sense of optimism about change. From the outset, “Away. . . Offshore. . . Adrift. . . Shifting Landscapes, Unstable Futures” accepted that Nantucket is in flux—as it always has been. Climate change became the inspiration for long-term designs to build more plentiful habitats and fisheries, more protective shorelines, and more resilient and flexible communities. In the face of malevolent change, of potential catastrophe, the studio instead envisioned powerful new ways of becoming for Nantucket.

Reclaiming Asian-American Garden History: Yoni Angelo Carnice researches the work and legacy of Demetrio Braceros at San Francisco’s Cayuga Playground

When Yoni Angelo Carnice (MLA ’20) first visited Cayuga Playground in San Francisco, he was struck by a wooden sculpture of a woman dressed in the traditional Filipino Maria Clara gown, with a graceful elegance that reminded him of his grandmother. The distinctively personal atmosphere of the park stayed with Carnice, and later became the basis of his year-long research project, “Eden of the Hinterlands: Reclaiming Asian-American Garden History,” under the Douglas Dockery Thomas Fellowship in Garden History and Design, sponsored by the Garden Club of America and the Landscape Architecture Foundation.

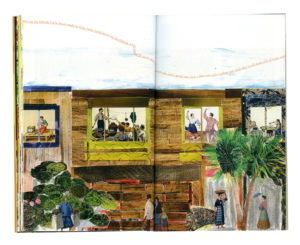

Spread from Yoni Angelo Carnice’s Sunlight Entered His Hands

Spread from Yoni Angelo Carnice’s Sunlight Entered His Hands

Spread from Yoni Angelo Carnice’s Sunlight Entered His Hands

Students, faculty, and alumni honored with 2021 Boston Society of Landscape Architects Awards

The Boston Society of Landscape Architects recently honored 21 projects by Harvard Graduate School of Design students, faculty, and alumni with its annual design awards. The program recognizes outstanding landscape architects, students, and projects based in Massachusetts or Maine. This year the awards were presented to projects that merited recognition in one or more of the following areas:- Exemplary social, cultural, educational, or environmental significance.

- Outstanding quality, craftmanship, creativity, or artistry.

- Unique and innovative technologies, techniques, or concepts.

- Advancement of the public’s awareness and perception of the field of landscape architecture.

Echo Chen, Kongyun He, and Michele Chen’s “Local Forest Coalition” Boston, MA.

Estello Raganit and Joan Chen’s “Slowlands: Making the Inter-Loughs Wilds” Northwest City Region, Ireland & Northern Ireland

Minzhi Lin’s “Retreating Plan” Wareham, Massachusetts.

- Agency Landscape + Planning, founders Gina Ford (MLA ’03), design critic in Landscape Architecture, and Brie Hensold (MUP ’07), design critic in Urban Planning and Design

- Carolina Aragon (MLA ’04)

- Copley Wolff Design Group, Inc, president and principal Lynn Wolff (MLA ’81)

- Crowley Cottrell, LLC, principal Naomi Cotrell (MLA ’02)

- Halvorson – Tighe & Bond Studio, principal landscape architect Cynthia Smith (MLA ’85)

- IBI Placemaking, principal John N. Amodeo (MLA ’82)

- Reed Hilderbrand, co-founder Gary Hilderbrand (MLA ’85), Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture

- SASAKI, principal James N. Miner (MUP ’01) with other GSD affiliates

- SCAPE, founder and principal Kate Orff (MLA ’97) with other GSD affiliates

- ScenesLab, founder and director Wendy Yifei Wang (MLA ’14) with other GSD affiliates

- Stoss Landscape Urbanism, founder and director Chris Reed, co-director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design Degree Program and Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture

- The VELA Project, co-principal Samantha Solano (MLA ’16)

Department of Landscape Architecture Announces 2021 Penny White Project Fund Recipients

The Harvard University Graduate School of Design’s Department of Landscape Architecture has announced this year’s recipients of the Penny White Project Fund. This grant program was established by the family of Winifred G. “Penny” White after White, a student in the GSD’s landscape architecture program, suddenly died of leukemia in 1976. The goal of the grant program is to “help carry forward Penny’s ideal of a culture which emphasizes a close relationship between people and nature in a cohesive living environment.” Now in its 44th year, the fund has announced 15 winning proposals selected through an evaluation process based on originality and innovation of projects, as well as their contribution to pressing challenges related to the fields of urbanism, landscape, and ecology. “From the role of female divers in the cultivation of submarine landscapes to the invisibility of disabled communities in urban environments, from big data analysis on the role of urban parks in pandemic times to archeological research in landscapes of self-determination and antislavery community construction, from the reconsideration of cultural identity in post-natural disaster recovery strategies to a prototypical farming experiment towards the restoration of Indigenous knowledge to the land, the research topics and strategies of this year’s selected student proposals address a range of conditions, technologies, and processes that are critical to the advancement of the discipline of landscape architecture today,” the Fund’s 2021 selection committee said in an email to the GSD community. The following GSD degree candidates will receive project funding for 2021: Ayami Akagawa (MLA I ’21) for “Feeling Rooted: Recovery from Natural Disaster and Identity Expression in New Home through Incremental Green Infrastructures in the Philippines” Chun Chen (MLA I AP ’21) & Sohun Kang (MArch I ’21) for “Landscapes of Women of Seas: Ama and Haenyeo” Echo Chen (MLA I ’21) for “Cultural Identities in Intangible Heritages: An Ethnologic Study of the Rural Communities Featuring the Covered Bridge in Southeast China” Jake Deluca (MLA I AP ’22) for “Un-Living Record: In Analysis of Our Social and Psychological Relationship to the Cemetery” Ian Erickson (MArch I ’24) for “On Becoming Productive: Representing Shifting Regimes of Value Extraction in the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Territory” Lianliu Guo (MLA I AP ’22) & Tianyu Su (DDes ’23) for “How Healthy Are They Doing in the Parks?: Understanding Urban Parks’ Perceived Health Impacts on Visitors Using Large-Scale Spatial Data” Aijing Li (MUP ’22) & Claire Wang (MUP ’22) for “Parks on the Edge: Big Data Analytics on Park Visits in Segregated Neighborhoods” Alison Maurer (MLA I ’22) for “Renewal and Reciprocal Labor: Exploring Iceland’s Ecologically Driven Economic Recovery” Caleb Negash (MArch I ’22) & Sam Valentine (MLA II ’21) for “Hope in the Dismal: Interpreting Landscapes of Self-Determination and Self-Liberation in the Great Dismal Swamp” Lara Prebble (MLA I ’23) for “Learning Through Play: Exploring the Roles of Outdoor Learning Environments in Finnish and Sámi Finland” Julia Rice (MLA I ’22) for “Perspectivist Agriculture: Reimagining Modern Food Systems through Indigenous Knowledge” Polly Sinclair (MLA I ’21) & Ada Thomas (MLA I ’21) for “The Spatial Imagination of Satoyama: Engaging Field Methods for Expanded Knowledge Production in Landscape Architecture” Shi Tang (MLA II ’21) & Xiaoji Zhou (MLA II ’23) for “Deaf Space in Landscape Design: Making Deaf Visible Through Spatial Investigation and Community Engagement in Wuhan, China” Michele Turrini (MLA II ’21) for “Sacrificial Land: Working with Peripheral Communities in Bangkok’s Decision-Making Watershed” Morgan Vought (MLA I ’22) for “If You Don’t Build Anything, You Don’t Exist: Redefining Tribal Recognition in Western Courts through Critical Ethnobotanical Cartography”Faculty-led Stoss Landscape Urbanism tapped to develop Boston’s first Urban Forest Plan

Stoss Landscape Urbanism, the design studio founded by Chris Reed, has been selected to develop Boston’s first Urban Forest Plan in collaboration with forestry consultant Urban Canopy Works. The effort will establish a 20-year canopy protection plan for the city and address topics including ecology, design, policy, environmental injustice, and funding. In addition to his role as founding director at Stoss, Reed serves as professor in practice of landscape architecture and co-director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design program at the Graduate School of Design. His colleague Amy Whitesides (MLA ’12), director of resiliency and research at Stoss and design critic in landscape architecture at the GSD, will lead the effort for the studio. “Our job is to fuel the project’s success by coordinating efforts between all the partners who each bring their own unique expertise,” explains Whitesides. “The ultimate goal is to maximize the health of Bostonians and their environment. We’re proud to work with the City of Boston on this shared commitment to Boston’s Urban Forest Plan.” The project will consist of scoping and assessing the existing state of Boston’s tree canopy while developing a plan to engage the community. Since tree removals on residential, private, and institutional properties have been the main contributors to canopy loss in the past five years, the Urban Forest Plan will also highlight policy tools to expand canopy on public streets and parks and control future loss on private property. The planning process will kick off in the spring of 2021 and will take approximately one year to complete. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh says that the Urban Forest Plan will “ensure our tree canopy in Boston is equitable, responsive to climate change and ensure the quality of life for all Bostonians.” He also emphasizes the importance of community input so that “residents in our neighborhoods have a central voice in this process.” Commissioner of Parks and Recreation Ryan Woods adds, “It’s no coincidence that many of the communities disproportionately impacted by poor air quality and the urban ‘heat island’ effect, also have inadequate tree cover. We’re excited to collaborate with these partners to find opportunities for growing tree canopy in the places that need it most.” Read more about the Urban Forest Plan on the City of Boston’s website and in World Landscape Architecture.With study of urban sanitation and flooding in Bangkok, Tina Yun Ting Tsai receives 2020 ASLA Award of Excellence

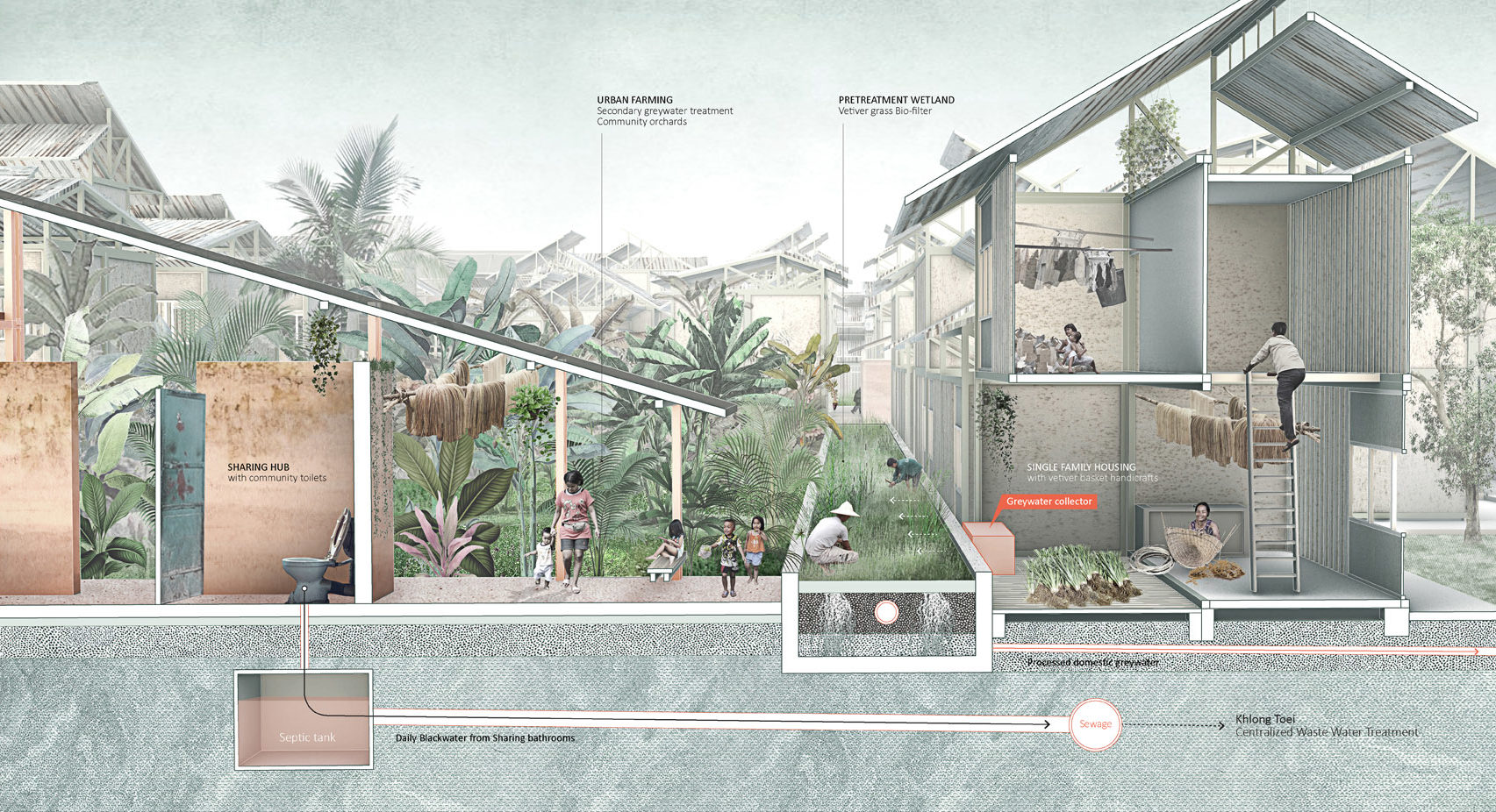

Tina Yun Ting Tsai (MLA ’20) has received an Award of Excellence in the Residential Design Category in this year’s American Society of Landscape Architects Student Awards . Her project, Informality as Filter: A Renewed Land Sharing Plan for Khlong Toei Community , examines informal settlements in Bangkok, specifically the Khlong Toei Community, as a way to understand and solve problems of urban sanitation and flooding. The project aims to preserve and protect local culture and citizens by introducing a land-sharing plan that promotes improvements of the existing water supply and food production chains. Professor of Landscape Architecture and Technology and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Niall Kirkwood and 2020 Design Critic in Landscape Architecture Kotchakorn Voraakhom were instructors in the option studio for which Tsai completed the project.

The ASLA jury explains: “Bangkok’s Khlong Toei community—an informal settlement along one of the city’s many canals—suffers from contaminated water, degraded health conditions, and the constant threat of relocation. But if this impermanent community were made a permanent and planned part of the city, as this project proposes, a mutually beneficial arrangement between inhabitants and city government could blossom. Starting with a multi-functional infrastructure of shared toilets feeding a wastewater treatment plant, greywater would be generated for use in community orchards. A retention pond and storage tanks would collect excess monsoon rainwater to be used during the drier months. By addressing this community’s needs, rather than shunting it to another temporary location, the local government would advance social equity while improving urban hygiene through a new, sustainable ecology.”

Addressing COVID-19 world, students take top honors at World Landscape Architecture competition

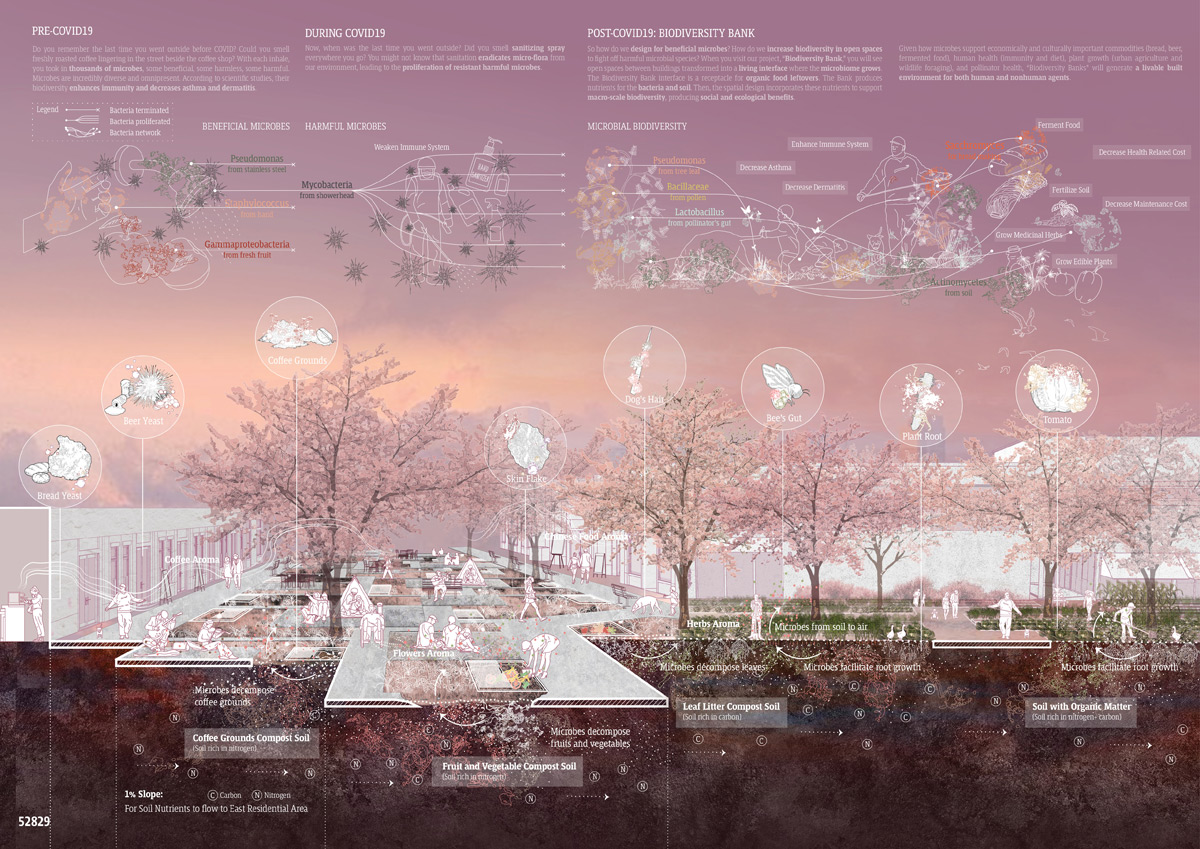

Harvard Graduate School of Design students Joanne Li (MLA I ’21) and Tian Wei Li (MLA I ’22) won first place in the World Landscape Architecture international competition Reimagining the Spaces in Between . Their project, “Biodiversity Bank,” was supported by a GSD Summer Emergency Fund grant and advised by Design Critic in Landscape Architecture Rosalea Monacella. The ideas competition challenged students to redesign an area in a fictional city impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In their entry, the students explained: “When you visit our project, you will see open spaces between buildings transformed into a living interface where the microbiome grows. Have you noticed that during COVID, alimentary and organic disposables have become more abundant, now that your home and kitchen are the center of your life? The ‘Biodiversity Bank’ interface is a receptacle for organic food leftovers. The Bank produces nutrients for the bacteria and soil. Then, the spatial design incorporates these nutrients to support macro-scale biodiversity, producing social and ecological benefits.”

“An innovative response that highlights the (often-overlooked) importance of soil and bacteria for health and well-being and maintenance of life,” noted the competition’s jury. “The solution presents the concept of city as a mutually symbiotic organism with everything inter-related. Interesting solution and compelling graphics. Appealing typologies such as orchards, meditation gardens and compost gardens that come together to create a startlingly different type of city solution.”

The runner-up prize went to Xi Chen (MLA I ’21), Sophia Xiao (MLA I ’21), Siqi Zhu (MLA II ’22), and Xuezhen Xie (Cornell) for “LIVING GROUND: Redefine six-feet distancing.” Their project looks at different scenarios for organizing outdoor activities on a six-by-six foot grid. “An aggressive scheme that reclaims public spaces for the public,” commented one juror.

Greetings from Dept. of Landscape Architecture

Dear Landscape Architecture Alumni,

Before I share news and updates from my fifth year as Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture, I would like to invite you to the upcoming GSD reception at the ASLA Annual Conference

on Landscape Architecture in San Diego.

One of the great satisfactions for me as Chair has been to reconnect with alumni at the ASLA reception. I am always impressed by how the GSD community appears so close and connected during this event. This year we have the privilege of welcoming GSD Dean Sarah M. Whiting, Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture, to our reception. Both Sarah and I look forward to seeing you on Saturday, November 16th.

It has been a busy and exciting fall at the GSD. We continue to develop climate change pedagogy, as I shared with you in my summer update. This topic permeates all aspects of the curriculum from studios to the history, technology and representation sequences. We are exploring design’s response to this greatest challenge and the many ways one can begin to conceptualize it, represent it, and develop technologies around it.

Fall option studios have taken our students around the world, showcasing how applicable the concerns of landscape architecture are, globally. Studios this year explore sites in Chile, France, Switzerland, Mexico, Virginia, and New England, and I look forward to sharing highlights with you in my next letter.

Last month, we hosted Professor Gareth Doherty’s DDes ’10 symposium and exhibition, Sacred Groves and Secret Parks: Orisha Landscapes in Brazil and West Africa. This conference explored the materiality and spatiality of Afro-religious diasporic practices. These large sacred groves, typically found in urban environments, manifest environmental understanding, memories, and cultural rituals through practices of botany, dance, and other forms of socialization.

Last week, Paola Sturla MLA ’11 delivered the annual Daniel Urban Kiley Teaching Fellow Lecture. Her research during the Fellowship explored how AI-based tools and computer simulations could support landscape architecture in the context of infrastructure planning, taking advantage of the user’s experience as a design variable. Established in 2011, this fellowship brings young practitioners and aspiring academics to teach with us for one academic year. For more information, please visit here.

I am pleased to report a new update to our lecture series. We have developed a more informal but dynamic lunchtime series where we provide an opportunity to expose students to conversational talks with visitors and visiting critics. The discussions have been rich and very well attended, and the format is woven into the fabric of everyday life at the school. This fall, it has been especially wonderful to hear Charles Eliot Traveling Fellows Alexandra Mei MLA ’17 and Michael Ezban MLA ’13 present their research.

I am also pleased to share that we have a wonderful new opportunity for our students: the GSD-Courances Residency Program. During this six-week residency, two students spend the summer at the Chateau de Courances in France, a 16th century domaine located in the Ile-de France region, 50 km south of Paris. Over the course of the residency, students learn about agricultural production, management of historical landscapes, and agroforestry, as well as develop a research program of their own. We have already had two groups of two experience this truly unique opportunity.

Looking ahead to next semester, we are delighted to announce that the Frederick Law Olmsted Lecture will be delivered by Swiss landscape architect Günther Vogt, accompanied by an exhibition of his firm’s work. The lecture will be held on February 6th and the exhibit will be on view in the Druker Design Gallery until spring break. If you are nearby, I encourage you to join us for our public program of lectures and exhibitions in Gund Hall.

Finally, congratulations to my colleague Niall Kirkwood, Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture from 2003–2009, who was recently named GSD Associate Dean for Academic Affairs. We are very proud to have someone from our department hold a major leadership position in the School.

In the meantime, I hope to connect with you in person at the ASLA reception on November 16th

.

Please stay in touch; I sincerely look forward to connecting with you.

Warm Regards,

Anita

Anita Berrizbeitia, FAAR, MLA ’87

Professor of Landscape Architecture

Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture

Greetings from Department of Landscape Architecture Chair Anita Berrizbeitia, FAAR (MLA ’87)

Dear Landscape Architecture alumni,

As I reflect upon another year as Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture, I am pleased to share with you a few highlights of news, pedagogy, and programming.

At a time of heightened political discord and global awareness around the hazards of climate change, I am especially excited to recognize the GSD’s ongoing role as convener on a wide variety of practical and theoretical topics.

In early September, the department hosted a two-day interdisciplinary conference, Envisioning Future Resilience Scenarios for the Boston Harbor Islands, funded by the James M. & Cathleen D. Stone Foundation, that brought together local experts from the University of Massachusetts Boston Sustainable Solutions Lab, The Nature Conservancy, the National Park Service, Boston Harbor Now, Woods Hole Group, the Boston Green Ribbon Commission, and the Stone Foundation, to share in a common conversation about building resilience for Greater Boston and to explore the role of the Harbor Islands in protecting Boston from coastal storms. The challenges raised at the conference, including sea level rise, real estate development, economy, infrastructure, recreation, quality of life, and ecology are an ongoing focus for the department and re-emerged as sites throughout the landscape core and options studios. Climate adaptation was also the topic of several studios on vastly different regions, demonstrating widespread effects. For example, Martha Schwartz GSD ’77 led a studio in North Adams, Massachusetts, hometown of MASS MoCA, which convened municipal and institutional leadership to address climate adaptation and sustainability in North Adams.

After the 2017-2018 exhibition, Landscape: Fabric of Details, in 2018-2019, we curated Mountains and the Rise of Landscape (photos above), a multi-media, seven-part exhibition that probed a panoply of questions surrounding the role of mountains in shaping our imagination, as well as their place in our collective landscape and architectural history. Pablo Pérez-Ramos MLA ’12, DDes ’18, Edward Eigen, and I assisted Michael Jakob in curating the exhibition, which included paintings, prints, film, and fiction alongside technical mapping and a sound installation of a melting glacier in the Swiss Alps by Geneva-based composers Olga Kokcharova and Gianluca Ruggeri.

We have much faculty news to share. Michael Van Valkenburgh, Charles Eliot Professor of Landscape Architecture, retired after 37 years of service. In his farewell address, the Olmsted Lecture in October, Michael gave an inspiring presentation on his long trajectory as an educator and a practitioner. We are very fortunate to have had him for so many years and wish him continuing success in the years to come.

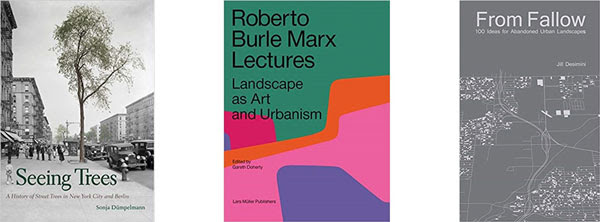

We were delighted to welcome two new faculty: Assistant Professor Pablo Pérez-Ramos MLA ’12, DDes ’18 and Associate Professor Teresa Gali-Izard. As always, our faculty have been very productive with scholarship and publications. Of note are Sonja Duempelmann’s Seeing Trees: A History of Street Trees in New York City and Berlin (Yale University Press, 2019), winner of the John Brinckerhoff Jackson Book Prize; Gareth Doherty’s DDes ’10 Roberto Burle Marx Lectures: Landscape as Art and Urbanism (Lars Muller Publishers, 2018), which was listed one of the top ten books of 2018 by the ASLA; and Jill Desimini’s From Fallow: 100 Ideas for Abandoned Urban Landscapes (ORO Editions, 2019). (Book covers featured above in order left to right).

In April, almost 100 alumni, family, and friends gathered in Piper Auditorium for a tribute to Professor Charles “Chuck” Harris GSD ’52, who passed away in January. Chuck served on the faculty between 1958 and 1991. Carl Steinitz, Nick Dines MLA ’68, and Chuck Jr. delivered remarks, followed by a reception and small exhibit of Chuck’s papers from the Loeb Library’s archives. Curated by Professor Niall Kirkwood and Special Collections Archivist & Reference Librarian Ines Zalduendo MArch ’95, the materials documented Chuck’s long career as a faculty member at the GSD.

Our studio offerings this year reflect the energy of our times—all are politically charged, culturally relevant, multi-scalar, and full of opportunities for invention. A few studios from the fall semester stand out. Alternative Futures for Al-`Ula, Saudi Arabia, sponsored by the Royal Commission for Al-`Ula and co-taught by Stephen Ervin and Craig Douglas responded to a call for entries by Professor Emeritus Carl Steinitz, who organized the International Geodesign Consortium, a collaboration of approximately one hundred institutions and projects worldwide, engaged in studies of similar scope and style in fall 2018. Teresa Gali-Izard taught the first in a series of studios sponsored by the LUMA Foundation. Set in the region of Arles, France, the studio explored the potential of regenerative agriculture, considering the rhizosphere—the region of soil around the roots of plants where nutrient exchange between microorganisms and plants occur—to explore the larger question of the relationship between humans and the natural world, and the role of landscape architecture in creating balance in the era of climate change. Finally, Marty Poirier MLA ’86 led a studio on Arlington National Cemetery that felt profoundly timely and emotionally laden, considering the design and entry sequence of one of our nation’s most sacred places. The studio asked students to transform the basic rudiments of arrival into a space of commemoration, considering the places that move us as a result of physical arrangements and design decisions.

In the spring, the excitement continued with studio sites that span the globe: Jungyoon Kim MLA ’00 and Yoonjin Park MLA ’00 led Landscape of Trans-Nationality: Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR) and Alternative Nature, which considered the landscape surrounding a new rail link between Russia and Korea; Aga Kahn Design Critic Catherine Mosbach taught Build with Life: Transformation + Formation: Landscape and Islamic Culture; Rosetta Elkin continued her work on coastal climate adaptation with The Monochrome No-Image, a studio sponsored by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in Sanibel Island, Florida. Niall Kirkwood and Gareth Doherty DDes ’10 led another politically charged studio that considered the future of Ireland after Brexit, Field Work: Brexit, Borders, and Imagining a New City-Region for the Irish Northwest; and James Lord MLA ’96 and Roderick Wyllie MLA ’98 addressed drought in the southern California landscape with SUPERBLOOM: Shelter, Drought, and Sculpture in the California Desert.

To better prepare our students to consider these exciting topics at the options studio level, we have made some strategic changes to the core curriculum. The second-year core studio is now focused on climate adaptation in two parts: third semester core studio explores climate change, adaptation, and risk as fundamental to the design of the built environment, utilizing the Boston Harbor as a case study, and the fourth semester core expands students’ reach to design urban environments in surrounding coastal communities.

The past two years have been marked by my intense engagement with university-wide committees. As I mentioned to those of you at October’s alumni reception in Philadelphia around ASLA (photos above), I was honored to serve on the Presidential Task Force on Inclusion and Belonging, and on the University’s presidential search advisory committee. As a planner, President Lawrence S. Bacow is a friend of the School, and we anticipate he will champion design in the broader university community. I also served on the GSD dean search advisory committee, and I am most excited to welcome our new Dean Sarah M. Whiting, who began on July 1. I thank outgoing Dean Mohsen Mostafavi for his support of our department during his 11 years as leader of the school. During his tenure, our department grew its student body and faculty ranks, as well as our presence in the culture of the school and university at large.

I would like to encourage you to join us on campus for a lecture or any of our public events this fall. Also, mark your calendars for the ASLA Annual Conference on Landscape Architecture in San Diego on November 15-18; I hope to see you at the GSD Reception during the Conference.

Please stay in touch; I sincerely look forward to connecting with you.

Warm Regards,

Anita Berrizbeitia, FAAR, MLA ’87

Professor of Landscape Architecture

Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture

Alumni Q&A / Kotchakorn Voraakhom MLA ’06

To help save her hometown of Bangkok, Thailand from rising sea levels and climate change, Kotchakorn Voraakhom MLA ’06 founded the landscape architecture design firm Landprocess and a social enterprise called Porous City Network , a landscape architecture social enterprise working to increase urban resilience. Through Porous City Network, Voraakhom works with communities throughout Southeast Asia to help find other ways to bring back green space and live with water. In response to the threat of flooding, Voraakhom has created an 11-acre Centenary Park at Chulalongkorn University that contains artificial wetlands and underground containers that can hold one million gallons of water. While at the GSD, she co-founded the Konkuey Design Initiative, an international partnership that works with communities in difficult landscapes to design and rebuild public space through a participatory process.

Voraakhom is a TED Fellow (watch her TED Talk here ), Echoing Green Fellow, Atlantic Fellow, and Asia Foundation Development Fellow and was named one of Fast Company’s “Most Creative People for 2019.” Also, she is also a highly active campaigner for public green space and is a design consultant for the Redevelopment Bangkok 250 project celebrating the city’s 250th anniversary. This November 2019, she will be a featured speaker at the ASLA Conference on Landscape Architecture’s session “No Time to Waste: Landscape Architecture and the Global Challenge of Climate Change,” along with fellow alumnus Kongjian Yu DDes ’95. Find more information here .

1. Tell us about your background.

Bangkok is where home is to me—it rooted in me are its tropical landscape, monsoon rain, humid air, canals, and rivers. I was born here, back when the city was nothing more than low density with rice fields. My parents were the first Chinese generation in Thailand, after migrating from the mainland during the country’s cultural revolution. Hardworking and business-oriented, they were also invested in my and my siblings’ education.

During my undergrad at Chulalongkorn University—the country’s oldest university or as many call it, the “Harvard of Thailand”—I first learned about landscape architecture. The profession was new and still not well-recognized in Thailand then. And at the age of 18, I didn’t know what it was exactly either. But years past and the more I realized what I was getting myself into. Today, I feel very grateful for having chosen this path to pursue in landscape architecture.

2. Why did you decide to come to Harvard for your MLA?

During my senior undergrad year in Thailand, I applied for internships in some of the top design firms in the US. Luckily, I became the first student from my department to intern in the US at Sasaki’s SWA Summer Internship program and then Design Workshop in the following year.

From Stuart O. Dawson MLA ’58 and Alistair MacIntosh (Sasaki) to William Byrd Callaway MLA ’71 (SWA) and Todd Johnson MLA ’82 (Design Workshop), I was fortunate enough to learn and work with several legacy makers in the field. During my internships in the US, I got the chance to collaborate with several GSD teachers and alumni, all who were people to whom I looked up and aspired to emulate.

3. Looking back, what experiences at the GSD were the most helpful in shaping your career?

There are those classes that would blow my mind about landscapes, especially from the classical lecture classes with Carl Steinitz (Landscape Planning), Richard Forman (Landscape Ecology), Niall Kirkwood (Brownfield), and John Stilgoe PhD ’77. Those classes shifted my entire worldview and remain relevant to this day.

I was a recipient of the Penny White Project Fund, which I used to study the aftermath of the Tsunami disaster in Thailand in 2004, those lectures began to make sense. During this research trip, I remember the voices of my professors sounding like a small symphony in my head! Their courses really helped me set up a foundation of understanding in the essence of landscape architecture and the potential it holds.

4. What about the GSD currently excites you?

As my work primarily concerns changing landscapes amidst our current climate crisis, I am always excited to see GSD’s option studios discuss the issue, especially with a focus across a variety of geographical regions around the world. I think by doing so, the GSD is taking the academic lead in the built environment and pushing new generations of designers to set the mission as their top design priority.

Award-winning students, professors, and alumni—like Assistant Professor of Architecture Holly Samuelson MDes ’09, DDes ’13 who has been awarded the Climate Change Solutions Fund grant by now Harvard President Emerita Drew Faust and many option studios focusing in this topic—put a big smile on my face and give me hope by creating a new standard of climate resilience design in academic and profession.

5. You have worked with Design Workshop and GSD Alumni Council Chair Emerita Allyson Mendenhall AB ’90, MLA ’99. How did this relationship come about?

I feel extremely honored to have had Allyson has my mentor, colleague, and friend, during my time at Design Workshop. She’s very organized as a project manager, and I learned a lot being part of her team. Moreover, I learned from her devotion to ambition, especially about the demanding nature of being a woman in the profession. Back then, she had just had her second baby, and she handled it beautifully.

With her expertise in writing from her English major at Harvard, she helped edit my GSD application essay and portfolio text, all with red lines and clear explanations for my Thai-sounding English. To this day, I still feel extremely grateful for her kindness.

6. You attended the GSD Bangkok Alumni Reception in March. What was this experience like? What value do you see in engaging with the GSD alumni community and connecting with the School?

The Reception was a great bonding time for me and my GSD friends! It was lovely for us Thai GSD alumni to physically reconnect—the most Thai alumni gathering I’ve ever experienced in Bangkok. Seeing Dean Emeritus Mohsen Mostafavi and GSD’s commitment to enriching the relationship with alumni in Thailand, I’m excited to see the future collaborations that will come out from our get-together. The reception reminded me of that need for belonging, and GSD and its people will always have a place for me.

7. When Thailand flooded in 2011, you were displaced from your home along with millions of other people. How did this influence your work?

I would have never thought my childhood pastime, boat paddling with friends in the floodwaters in front of my house as a little girl, would later become a catastrophic disaster. It was an awakening period for me to be displaced in my own homeland, along with millions of my people.

Bangkok is one of the most threatened cities by climate change, and the concrete urban infrastructure we have has made us very vulnerable to future uncertainties. With no excuse, as practitioners of the physical built environment, we, too, are part of the problem in our work and impact in urban development. But as a landscape architect, I know I can be part of the answer for urban flooding and other environmental issues, and so I work every day to execute those solutions and enable people in professions different and alike to do the same.

8. Tell us about your professional career. You founded the landscape design studio Landprocess and the social enterprise Porous City Network. What drives your work?

Practicing with public space takes a particular intersection of designer instincts and entrepreneurship to work creatively and push through projects that truly benefit society. Most design firms in Thailand survive by working with commercial projects like condominiums or malls, but I want to create an innovative player in today’s challenging business climate. Landprocess

commits to provide service in public projects and difficult urban landscape contexts, and while it hasn’t been easy, this is my passion and ‘easy’ isn’t what I’m looking for!

Landprocess has been operating for seven years, while Porous City Network (PCN) is entering its third. With the experience of founding and co-founding several organizations, I’ve learned how to establish and grow socially-impactful ventures, as well as attracting funding sources to not only sustain but elevate them. Both organizations are currently active with their original missions intact at the core of every project.

PCN addresses one broad but critical question: how can we make a city porous? Decades of rapid urbanization worldwide has created vulnerabilities and increased water stresses in our urban landscapes. Urban sprawls destroy cities’ natural eco-services, their resilience, and their ability to adapt. In Thailand, agricultural land and ecological green patches that once absorbed seasonal flood and cycles of monsoon rain have been paved over by urban development, degrading urban ecology and increasing flooding and stormwater pollution. PCN works to revive traditional knowledge about our ecology and reintegrate that back into our approach in sustainable urban development.

In addition to producing landscape solutions to mitigate urban flooding, PCN’s mission also revolves around education advocacy and participatory processes in co-creating those innovations. As a landscape architect, I believe we are obligated not only to contribute but also spread these solutions across a diverse range of regions and professions.

9. You’ve spoken about your work at many conferences including TED Conference in Vancouver (2018), and a United Nations Panel on social enterprises (2018). and keynote opening for United Climate Change, NAP Expo 2019. On Monday, November 18, you will be speaking at the American Society of Landscape Architects Conference on Landscape Architecture on the panel “No Time to Waste: Landscape Architecture and the Global Challenge of Climate Change.” The panel also includes fellow GSD alumnus Kongjian Yu DDes ’95. How did this panel come about? What are you looking forward to most about ASLA?

Firstly, I would like to thank ASLA for inviting me to the special occasion. I’d like to believe my role at the conference is in providing context about the difficult landscape I come from, about the challenges I face as a landscape architect in solving environmental issues in my city and region. While climate change is a global problem, its impacts are very site-specific—so are its solutions, which need to be implemented under cautious consideration to the location’s ecology, topography, culture, and budget. First-world solutions shouldn’t be copy-pasted to developing countries without a deep understanding of the places’ social and environmental complexity. And because of that, I am honored to be able to share my insights from the landscape architecture profession which has plenty to offer to solve the crisis.

This year’s ASLA will be my first, and I am looking to reconnect with my colleagues and friends and share what we have developed in our careers. Kongjian Yu DDes ’95 and Hitesh Mehta are both big-name landscape architects who I respect as my role model coming from a generation of practitioners before me. For this climate change discussion, I’d like to share my situation with them and discuss how we can work in our field to confront climate emergency together.

10. What advice do you have for GSD students and/or alumni?

My time at GSD was a period of my life when I explored and searched for new territory in who I was as a landscape architect. Even more so, it was the time I found my people. Some might say it’s a competitive place, cold and grey, but for me, it was a warm and welcoming place where I made friends for life.

These weren’t just the friends for Beer ‘n Dogs—they were the ones you find along your journey when you needed someone to reflect upon yourself with or see a different perspective whether in work or life. So I’d suggest you look all around—they may not look like one, but everyone around you is critical, funny, passionate, and hardworking in their own ways—just like you! Learn not only from the class and professors, but also your friends and classmates.

11. Where do you go to feel inspired and fulfilled?

I go to landscapes and its people and let their interconnected relationships fascinate me. I love to see beautiful humanmade landscape architecture, but what stuns me more is seeing the meaningful interplay they have with their surrounding landscapes and lifeforms.

While this line of work can be challenging and bittersweet, to see my projects interwoven with my passion and purpose is exciting, fulfilling, and all worth it. Although it’s important to work to address the needs of your clients, I think what’s more necessary is working for the place and its people.

12. What is the difference in practice between the US and Thailand?

I learned a lot being a practitioner in the US, with that experience permanently firmly embedded in the foundation of my life-long career.

One time, I was tasked with designing a casino in Las Vegas, and while that may sound like a dream project to many, it made me question my role as a landscape architect. What and who was the landscape for? Working on a project that provided no positive deep impact or purpose, it is meaningless. I realized I valued public use projects much more, contributing with purpose to a place in need and people at risk. I felt the need to create a landscape that made sense not only to me but the landscape and people that lived upon it.

With that realization, I decided to return home to continue another chapter of my life. It definitely has not been the easier path, but regardless, I feel more alive and fulfilled to now serve the land I come from and its people in need.

13. What would surprise us about you?

Surprise #1: We—my Thai GSD alumni friends, Professor Niall Kirkwood, and I—are planning on launching the first option studio in Bangkok, where I will teach and organize courses in collaboration with GSD and universities in Thailand. If it’s possible and when it’s official, I’d love to invite GSD students to sign up for it. Bangkok is a rapidly growing city on a delta landscape, and we are one of the most at-risk cities of climate change with good food, so we need all your help!

Surprise #2: I’m excited for my green roof at Thammasat University to be completed very soon! It will be the biggest one yet in any single building in Southeast Asia, equipped with landscape solutions to tackle climate change using urban farming and rain and runoff utilization as the architecture’s skin. I look forward to sharing more about this project with you by the end of this year.

14. Please let us know about anything not addressed here that you’d like to share with readers.

You know those exhausting days and nights when you put more than 100% into your project, just to present it to a big-name guest lecturer in one of your courses? They were extremely tiring, but you know that big smile you get hearing the “great work!” coming from those lecturers? It definitely paid off at your desk crit and pin-up, and I’m sure it will, too, later in your future work. Weren’t they more than 100% worth it?

I hope the profession we share flourishes in helping the world deal with the pressing issue of climate change, and we can all contribute by putting it as our top priority in design and its implementation. Here are some links to my work that I’d love to share with you all. We journey together to a goal to make our planet Earth better each day, and I hope we can get there as soon as possible with our conjoined efforts.