Meriem Chabani Designs Sacred Spaces within the Profane

Several years ago, Meriem Chabani, Aga Khan Design Critic in Architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), spent countless hours learning to hand-tuft wool rugs in the Berber tradition for which her homeland, Algeria, is globally renowned. The result, Mediterranean Queendoms, was exhibited in the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale . A richly textured triptych in earthen hues, blues, yellows, and grays, the carpet tells the story of Chabani’s mother’s and two grandmothers’ homes in iconographic imagery that evokes animals, Berber patterns, and cityscapes, to chronicle her family’s diasporic journey and ability to bring home with them.

“In many different cultures, including my own,” explained Chabani, “textiles have historically been a way of meaning-making, of carrying stories and transmitting knowledge. I explored how we could use one form of textile crafts—carpets—to provide full representation for housing.”

As an Algerian who grew up in France and experienced the long-lasting effects of colonization and war, Chabani knows how it feels to “exist in the periphery,” even as she “deconstructed its existence.” She turns to the language of feminist theorist bell hooks to “put the margin at the center,” and grounds her designs in “spiritual and sacred practices with the built environment,” centering care and “acts of faith” that help us to more productively share space together.

The rug serves as a symbol of how women hold familial and cultural information in the diaspora, carrying it with them just as they roll up and transport the carpet “from one home to another, across the sea,” writes Chabani on her website. It is unrolled again in a new home where women “care for, maintain and transmit resources, values, presents, medical care, family objects, furniture.”

This fall, Chabani spoke at the GSD about the place the carpet holds in her practice and how her firm, New South, co-founded with John Edom, creates spaces for diasporic communities from the Global South and foregrounds their architectural heritage within the North. Citing theorist and writer Paul B. Preciado, she argued in her talk, “South South Cosmogonies,” that the South is a fiction created in contrast to the North, “shaped by subjugation and uneven power relations.”

“The South is the site of extraction,” she explained, “the North is the site of value-making. The South is the site of magic, feminine, queerness, gold, and coffee; the North is the site of science, masculinity, coordination.”

Her firm’s recent projects include a religious and cultural center in Paris and the Muqarnas Pavilion, the latter of which was inspired by the muqarnas used for centuries in Islamic architecture. “Muqarnas are a decorative molding,” Chabani explained in her talk at the GSD, “applied to ceiling vaults . . . across Islamic culture. At first glance, they appear to be intricate decorative ornamentation, but they also serve a practical purpose.”

She went on to explain that they may have evolved as a result of the shapes made when a brick structure transitions from an octagonal floor and walls to a domed ceiling, and that they reflect the Islamic “non-figurative approach to ornamentation.” The shape continued to evolve and is now made from plaster. She decided to use it in her design because it would allow her to explore a sacred space installed in a profane setting, and to “reassert constructive and construction innovation as central to contemporary Islamic architecture.”

An outdoor installation that Chabani designed in collaboration with Radhi Ben Hadid, a structural engineer, and Gorbon Ceramics, the pavilion is made of many half-cupolas molded in industrial grade, vibrant blue ceramic. Muqarnas are typically installed in a dome or arch as a decorative element, but Chabani’s goal was to create a self-supporting half-dome of muqarnas. She found that, because ceramics change in the firing process, the molds could not be 3D-printed and were instead hand-crafted.

The installation is what she calls in French a courage perdue, or lost risk, as it required reinforcement with concrete that’s then covered with soil and planted with greenery. Installed in the grass with trees behind it at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Saint-Étienne, in France, the pavilion looks like a bright blue shelter hidden within nature. Visitors can walk into the curved space that’s been used for performances and presentations; Chabani noted that it’s also enticing for curious children.

Another design that combines secular and religious spaces, the mosque and cultural center she has designed for the 11th arrondissement in Paris would replace the current mosque that the community uses, in a renovated paper factory. Chabani cited the building’s dilapidated facilities and insufficient space for the number of people who want to worship as some of the primary drivers for a new mosque. But, these issues are part of a systemic problem, she noted, explaining that Paris currently meets only about seven percent of the population’s needs for mosques, and that France is systematically eliminating worship spaces in immigrant communities. Government-run housing units for immigrants are currently being renovated, and the new spaces for worship are too small for communities to use together.

When the Muslim community in the 11th arrondissement asked Chabani to help them design a mosque, she thought about contemporary attempts to modernize mosques that only create caricatures without capturing their essence. So, she began with a fundamental question: What is a mosque? She determined that it must be “oriented toward Mecca, provide a clear distinction between sacred and profane spaces, and allow people to pray collectively.” Because the lot is just over 900,000 square feet, Chabani and her team deployed the vertical space, using a Chambord stair system to allow people to filter into the upper levels of the mosque without waiting until lower levels are full, eliminating the issue of overflow into the street as people wait in line to pray.

She went on to consider what might happen if the traditional architectural elements of a mosque—the minaret, dome, and pointed arches—were not prioritized. Instead, she found her way with the words, aya tonerre, which translates to “God is light upon light.” Her design prioritizes the movement in the space, as people pray five times a day, and challenges the idea of erasure of the community with chain-metal cladding—a nod to the metal working history of the neighborhood—that can be opened or closed around the “glass house.” Within the building, multifunctional rooms, including a library, exhibition space, and offices can be divided with floor-to-ceiling sheer curtains, adaptable for various sacred and secular purposes.

In her architecture studio course this semester at the GSD, “Anchoring Acts,” she continues to explore relationships between sacred and secular spaces. She led students through a study of New Orleans, urging them to consider “not only greener technologies” in the service of environmentalism and sustainability, but also “the affective and sacred dimensions of care.” An anchoring act, she explained, is a “ritual or relationship based on spiritual or sacred practice with the built environment.”

Similarly, Chabani sees an opportunity to learn from the traditions and rituals of the many diasporic communities in New Orleans—African, Caribbean, Indigenous, Arab, Spanish, French, Creole, Cajun, Pacific, and Vietnamese—elucidating how “place, memory, and belief shape the built environment.” She calls their overlapping cultures “entangled cosmologies.” To learn more about those intersecting communities and their influence on American culture, during the studio course’s trip to New Orleans, students visited iconic Congo Square, known as the musical center of the city.

It was there that, as Freddi Evans, author of Congo Square: African Roots in New Orleans , explained in a lecture to Chabani’s class, enslaved Africans who were taken from different regions of their home continent—Bight of Benin, Central Africa, Sierra Leone, and Senegal—would intermingle on Sundays, sharing instruments, songs, drumming, and other traditions from their homelands, leading to the creation of a range of musical instruments, dances, voodoo and other spiritual practices, and, of course, jazz.

Together, the group also attended a Second Line, a ceremonial parade with music through the Tremé neighborhood, and took a tour of “Geographies of Displacement” with 2025 Loeb Fellow Shana M. griffin. griffin’s multimodal series DISPLACED “traces [New Orleans] geographies of Black displacement, dislocation, confinement, and disposability in land-use planning, housing policy, and urban development . . . highlighting moments of refusal, rupture, and protest.” She encouraged the students to “reimagine space-making and abolition strategies that value Black life.”

For examples of this kind of abolitionist work in the built environment, the group met with a variety of organizations focused on underserved communities in the city, including Tulane’s Albert Jr. and Tina Small Center for Collaborative Design, directed by 2013 Loeb Fellow Ann Yoachim .

As students worked towards their final projects for the course, Chabani described the wide range of themes they explored, from “fire rituals and carbon capture, probing the tensions between sacrifice, material performance, and durability” to “rituals of rebuilding, where architecture becomes a medium for repair, knowledge transfer, and resilience in the face of climate catastrophe.” One student, for example, mapped people’s movement around Congo Square to design a gathering space that also functions as a parking garage and will eliminate the need for nearby parking lots, while another applied lessons from bamboo scaffolding experts in Hong Kong to create a building at the local technical school that can serve as a model and learning space for hybrid bamboo-and-wood buildings.

Moving ahead, Chabani continues to probe the connections between sacred and secular spaces, re-centering the Global South, and exploring how these threads can lead us to better care for our environments and each other.

Practicing Growth in a Finite World: An Ethics Of Patience and Pragmatism

Two themes—pragmatism and time—dominated last week’s Practicing Growth in a Finite World, a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) panel presented as this year’s Carl E. Sapers Ethics in Practice Lecture and hosted by the GSD Practice Forum. Four experts—one philosopher and three built‑environment practitioners—approached the question of growth and sustainability in a resource‑constrained world from distinct vantage points. Their conversation, urgent yet mindful of the incremental pace of change, surfaced ethical frameworks for 21st‑century practice and examined how designers can work within today’s constraints to make room for future transformation.

Architects, planners, and designers face a constellation of ethical quandaries. Moderator Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti, assistant professor in practice of architecture and chair of the GSD Practice Forum, set the stage with a sobering fact: buildings produce more than 40 percent of global carbon emissions. In an age of relentless urban growth, that number captures a central paradox. Political and professional pressures demand speed—the rapid delivery of affordable housing and public infrastructure—even as every new square foot adds to the planet’s carbon and waste loads. Technology can scale these efforts , magnifying both progress and harm—harm potentially so devastating that some commentators argue for a moratorium on new construction. Beneath it all runs a familiar tension: the push to maximize returns for clients versus the desire to create culturally meaningful work. As Christoforetti observed, “the context for 21st-century design is thus a pressure cooker of external complexities.”

The urgency of the moment was brought into focus by philosopher Mathias Risse —Berthold Beitz Professor in Human Rights, Global Affairs, and Philosophy and director of the Carr-Ryan Center for Human Rights at the Harvard Kennedy School. “Architecture and design are at an ethical crossroads,” he argued. The only ethically responsible path forward, Risse suggested, is to become a “pragmatic moral agent”—someone who “works within existing systems to minimize environmental impact, promote sustainable practices, and gradually shift attitudes toward building and consumption.” The practical and temporal dimensions he outlined echoed through the reflections of the remaining three panelists.

Jane Amidon (MLA ’95), professor of landscape architecture and director of the Urban Landscape Program at Northeastern University, examined how practitioners navigate questions of public space, nature, and human experience. She pointed to large-scale, dynamic projects, such as those involving ecological rehabilitation and landscape maturation, that rely on “small tools of incremental change” and sustained advocacy—efforts that unfold over decades. Working closely with communities, she noted, designers can help shift expectations and foster acceptance of new approaches, such as coastal landscape projects in recent years that make room for rising water rather than trying, futilely, to hold it back.

“I’m interested in how design can work within the systems of today and catalyze or allow for the possibility of a different tomorrow,” said Neeraj Bhatia, advocating a similar forward-looking approach. A professor at the California College of the Arts and founder of THE OPEN WORKSHOP , a design-research practice, Bhatia discussed Lots Will Tear Us Apart, a recent collaboration with Spiegel Aihara Workshop that proposes a new housing typology for San Francisco. The project reimagines community living by rejecting conventional property division and private ownership, instead using prefabricated cores and flexible configurations to promote alternative living arrangements that allow for higher density and communal land. “The project asks how the architect can preconfigure the conditions for more collectivity, sharing, and social resilience,” Bhatia explained. “It offers the possibility of other ways of life that can slowly reconfigure the system over time.”

Dr. Dana Cuff , a professor at UCLA, concluded the discussion by focusing on spatial justice and the work she leads through cityLAB , a UCLA-based non-profit research and design center. “In every form of practice,” Cuff observed, “there are ways of doing work that step outside a capitalist model, whether it’s pro bono efforts in a traditional practice or … an organization dedicated to something like affordable housing.” One of cityLAB’s first breakthroughs was its research into the feasibility of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in California, which helped shape 2016 legislation that opened the door for an estimated 8.1 million ADUs statewide. Building on that momentum, Cuff and her team turned their attention to small vacant lots throughout Los Angeles, launching Small Lots, Big Impact in spring 2025—a design competition aimed at prototyping and promoting housing on underused parcels. As she remarked in response to an audience question, “Capitalism is the air we breathe. Once you accept that, you have to ask yourself: what can you do to shift the trajectory, even slightly, and open up new possibilities?”

Cuff’s reflection echoed a point made earlier in the evening by Sarah Whiting, dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the GSD, who opened the event by emphasizing design schools’ ethical responsibilities—to their students, the profession, and humanity. “If we want our students to advance the world, making it more beautiful, more just, more ecological, and more durable, we need to work with them to envision what practices can enable that,” Whiting said. “As we push the envelope of building envelopes, facades, structures, materials, forms, and programs, we need to push the envelope of practice itself.”

In the end, Practicing Growth in a Finite World revealed less a crisis than a recalibration. The panelists’ insights traced an ethics of patience and pragmatism—an acknowledgment that meaningful change in the built environment unfolds not only through grand gestures, but through persistant, systemic work. In confronting the limits of growth, they offered a hopeful reminder: that design’s true power lies not only in what it creates, but in how it reimagines the conditions for collective progress.

Sameh Wahba: Expanding the Canvas of Sustainable Development

Sameh Wahba (MUP ’97, PhD ’02) navigates one of the most complex landscapes in global development. As the World Bank’s Regional Director for Sustainable Development in Europe and Central Asia, Wahba heads efforts to eradicate poverty and promote inclusive development in an area stretching nearly 5.5 million square miles, from Kazakhstan’s desert and steppes to the Mediterranean coasts. Within this vast territory, his mandate covers a diverse population and an extraordinary range of issues—helping countries strengthen agriculture and food systems, manage water and natural resources, adapt to climate change, build resilient cities, and foster social inclusion. With a $10 billion portfolio and a team of 200 experts over 23 regional offices, Wahba is tasked with creating a vision of sustainable growth that can withstand both the pressures of today and the uncertainties of tomorrow.

“For me, the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) was a good entry for this work; it gave me a place to build on my background in architecture while pushing me toward new ways of thinking,” Wahba reflects. Indeed, over the course of his studies in the GSD’s master of urban planning and doctoral programs, he came to embrace design as inseparable from economic, sociological, and environmental concerns. Whether in his efforts with the World Bank or his sustained engagement with the GSD, this expansive framework continues to guide Wahba’s work today.

The GSD as Springboard: From Architecture to Global Development

Wahba’s professional path began in Cairo, Egypt, where he completed a master’s degree in architecture with a focus on engineering. Interested in housing, he was inspired by the work of Hassan Fathy, whose pioneering low-cost housing projects demonstrated that affordability, culture, and beauty could align. But Wahba also recognized the limitations of such community development initiatives; for example, Fathy’s vernacular-inspired work didn’t always resonate aesthetically or functionally with the needs of those for whom he designed.

Arriving at the GSD, Wahba began to further explore the complexities of housing and community development. “My first couple of years, I complemented my existing design and spatial perspective with more quantitative tools, understanding the economics, the real estate finance dynamics, and the urban politics,” he recalls. The academic freedom allowed him to experiment broadly as he deepened his knowledge, drawing from design studios, planning courses, and policy seminars at the GSD, other Harvard schools, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). This latitude proved transformative. “The GSD was a place where I could take Alan Altshuler’s ‘Urban Politics and Planning’ at the same time as Rem Koolhaas’s ‘Harvard Project on the City,’ and then take Rafael Moneo’s ‘Design Theories in Architecture,’” Wahba notes. For his PhD committee, Wahba assembled diverse thinkers, working with Jerold Kayden on public-private development, Bill Doebele on international development, and Tony Gómez-Ibáñez on economics and public policy. Drawing from all three areas of expertise, he ultimately devised his own formula for work on land and housing policy. “The breadth of choice, within the GSD as well as across Harvard and MIT,” Wahba reflects, “gave me the intellectual flexibility that continues to shape my work.”

Overall, at the GSD, Wahba reframed his approach to urban and development challenges. “The school became a springboard for me; it let me experiment and connect design with the real forces shaping cities,” he explains. Wahba began to see design as a framework that could connect with economics, policy, and governance to create holistic solutions. As Wahba notes, the GSD’s multidisciplinarity “allowed me to expand the canvas. Whether it’s working on land policy, housing, or resilience, I’m always drawing from that foundation of ‘design-plus’.”

Integrating Insights to Create Solutions

Through his work with the World Bank, Wahba applies this “design-plus” concept within an amazingly broad context. While he currently directs efforts in Europe and Central Asia, throughout his 22 years with the institution he has been part of sustainable growth initiatives in regions around the world facing the pressures of rapid urbanization, environmental degradation, social inequality, and the intensifying impacts of climate change. Reflecting this complexity, Wahba’s portfolio encompasses projects across sectors, from improving land administration to supporting agricultural resilience to advancing energy and water sustainability. His work also includes helping governments strengthen disaster preparedness and recovery, a responsibility that has grown in urgency as extreme weather events increase in severity.

Crucially, Wahba emphasizes cooperation across domains, balancing technical expertise, policy advice, financing, and diplomacy—aspects that draw directly on the intellectual foundation he built at the GSD. “You cannot solve the housing crisis only with architecture,” he observes. “You have to think about finance, about land markets, about politics, about resilience, and you must integrate them all.” It is this perspective that Wahba brings to the World Bank. “Mainly we’re financiers,” he explains, “so we support governments in doing things. Yet with our research and the analytics, we’ve expanded the boundaries of the practice. And I’ve managed to introduce a stronger design lens to our work.” Since Wahba has joined the World Bank, he has helped countries grow significantly into issues of climate action, decarbonization, and adaptation. “We have moved into urban design, public spaces, nature-based solutions such as wetlands and mangroves—which serve decarbonization and flood mitigation purposes, but also in terms of creating green spaces, accessible spaces, thinking about mobility in the city.”

For Wahba, “expand the canvas” is more than a metaphor—it is a method of integrating insights across disciplines to generate practical, impactful solutions. It also means rethinking systems rather than simply delivering projects. For instance, in disaster prevention efforts, Wahba’s team helps rebuild infrastructure with embedded resilience measures that allow communities to emerge stronger. An example of such work is Beddagana Wetlands Park , part of the larger Metro Colombo Urban Redevelopment Project in Sri Lanka, which Wahba headed during an earlier role as Global Director for Urban, Resilience, and Land at the World Bank. His team transformed an 18-hectacre garbage strewn area into a thriving urban wetland that provides a recreational zone, regulates flooding, moderates atmospheric temperatures, and hosts an array of flora and fauna. At the same time, this regenerated wetland offers educational opportunities for local children and, through the development of concessions, generates revenue. Envisioned as a nature-based solution for flash floods, Beddagana Wetland has become a major amenity in the city, increasing biodiversity, residents’ property values, and their quality of life.

Another remarkable project occurred in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, following a massive mudslide that killed hundreds of people and displaced thousands more. In addition to rehousing the affected population, the Sierra Leone Urban Resilience Program involved planting more than a million trees in the city for soil stabilization. This tree planting and care campaign simultaneously doubles as an income transfer program to alleviate poverty, with poor households engaged as environmental stewards. In exchange for pay, they plant the trees, grow them, and document their growth. Such creative programs support urban improvements while bolstering opportunity.

In many cases, Wahba’s team introduces new practices—such as the recently established Türkiye Water Circularity and Efficiency Improvement Project , which expands wastewater treatment and addresses water scarcity through the reuse of that water for agriculture and irrigation. And even seemingly small interventions can have a huge impact. Wahba cites an informal settlement upgrading program in Kenya where the installation of high mast lighting has changed communities: shops stay open later, kids without electricity at home bring books and study under the light, and crime rates drop. “It’s a complete transformation just because you put in a single light pole,” Wahba says.

These initiatives reflect the interconnectedness of sustainable development and the imperative to bridge realms that, at times, have been treated as distinct. They also echo the GSD ethos of design as a framework that unites physical form with social, economic, and political realities.

A Continuing Conversation with the GSD

Even as he leads an expansive portfolio at the World Bank, Wahba remains closely connected to the GSD. Since July 2024 he has served as co-chair of the GSD Alumni Council, first with Nina Chase (MLA ’12) and now with Alpa Nawre (MLAUD ’11). Through the Alumni Council Wahba co-created Design Impact —a global speaker series in which practitioners share their visionary work on critical yet often overlooked topics, including upgrading slums and accessible design. Wahba is also a member of the Dean’s Council, through which he takes part in high-level discussions that help further the GSD’s reach within the university and beyond. He also recently began as an appointed director of the Harvard Alumni Association, representing the GSD. Indeed, Wahba sees the GSD as a vital incubator for the next generation of urban and development leaders—individuals who will tackle the increasingly complex challenges of climate adaptation, migration, housing crises, and social equity.

Looking back, Wahba positions his GSD experience as a reframing of design and the opportunities it brings. His wide-ranging explorations prepared him for a career where architecture merges with policy, spatial design intertwines with economic systems, and resilience demands creativity across disciplines. As Wahba affirms, “that multidisciplinary approach formed at the GSD comes to life in everything I do now.”

How a Collaboration Between Design and Real Estate Advances Equity in Mumbai

Students in Rahul Mehrotra’s “Extreme Urbanism Mumbai” Graduate School of Design (GSD) Spring 2025 option studio faced a challenge that was intended to take them “completely outside their comfort level,” said Mehrotra. “We set a wicked problem that exposes them to an unfolding of interconnected issues.”

Mumbai, set on a peninsula on the northwest coast of India, is one of the largest and densest cities in the world, with a population of about 21.3 million residents and more than 36,200 people per square kilometer—most of whom face a stark housing crisis. Approximately 57 percent of Mumbai’s population lives in informal homes, many of whom work in nearby housing complexes where they’re employed by the upper-class residents. Most of the students in the studio had never been exposed to what Mehrotra describes as “extreme conditions, in terms of density, poverty, and the juxtaposition of different worlds in the same space.”

“Mumbai is like nothing I’d ever seen before,” said Enrique Lozano (MAUD ’26), who had previously traveled to other parts of India. “There’s no designed urban form; skyscrapers are scattered throughout the city. It’s on a former wetland, so there are issues with water, one of my research areas.”

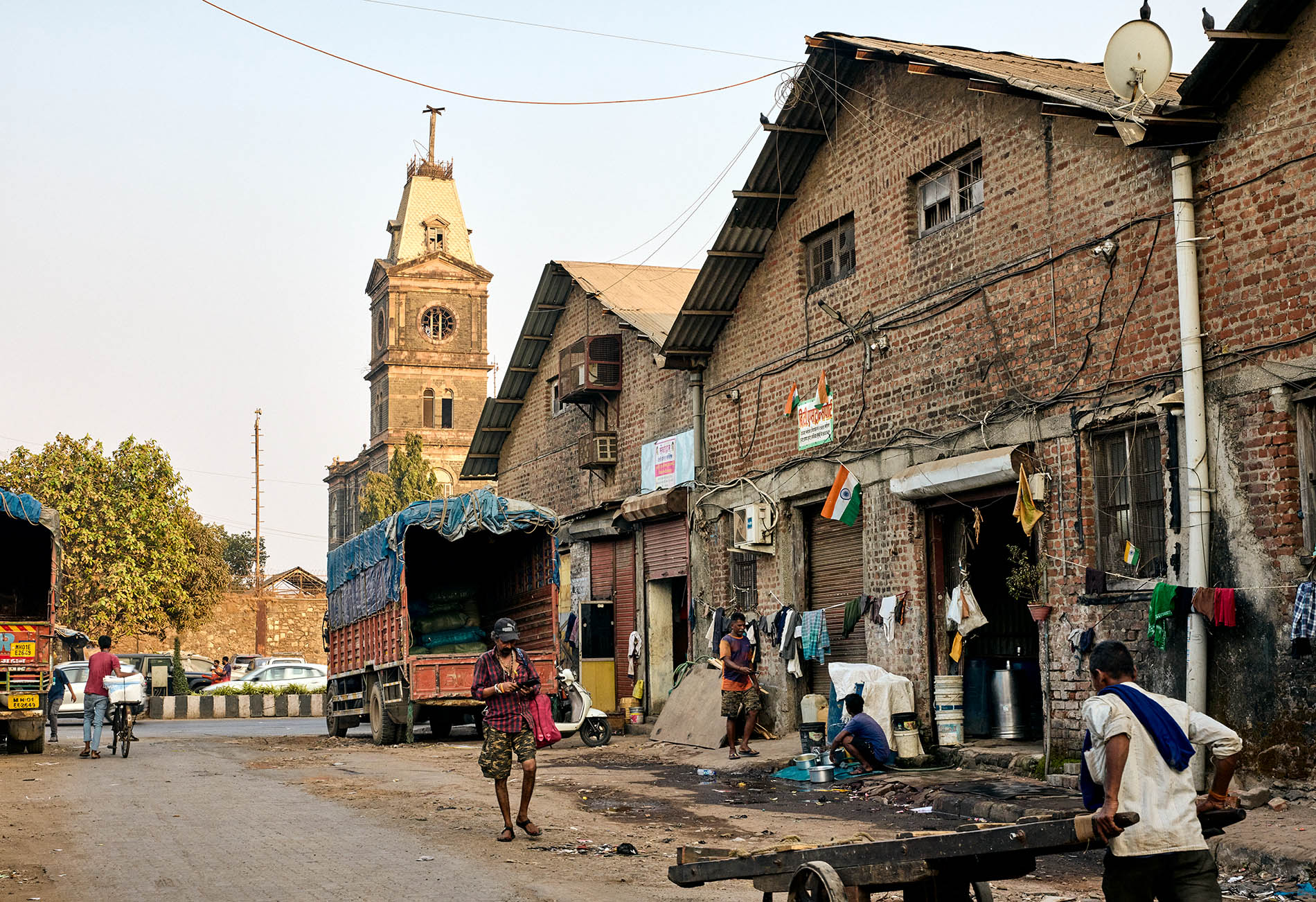

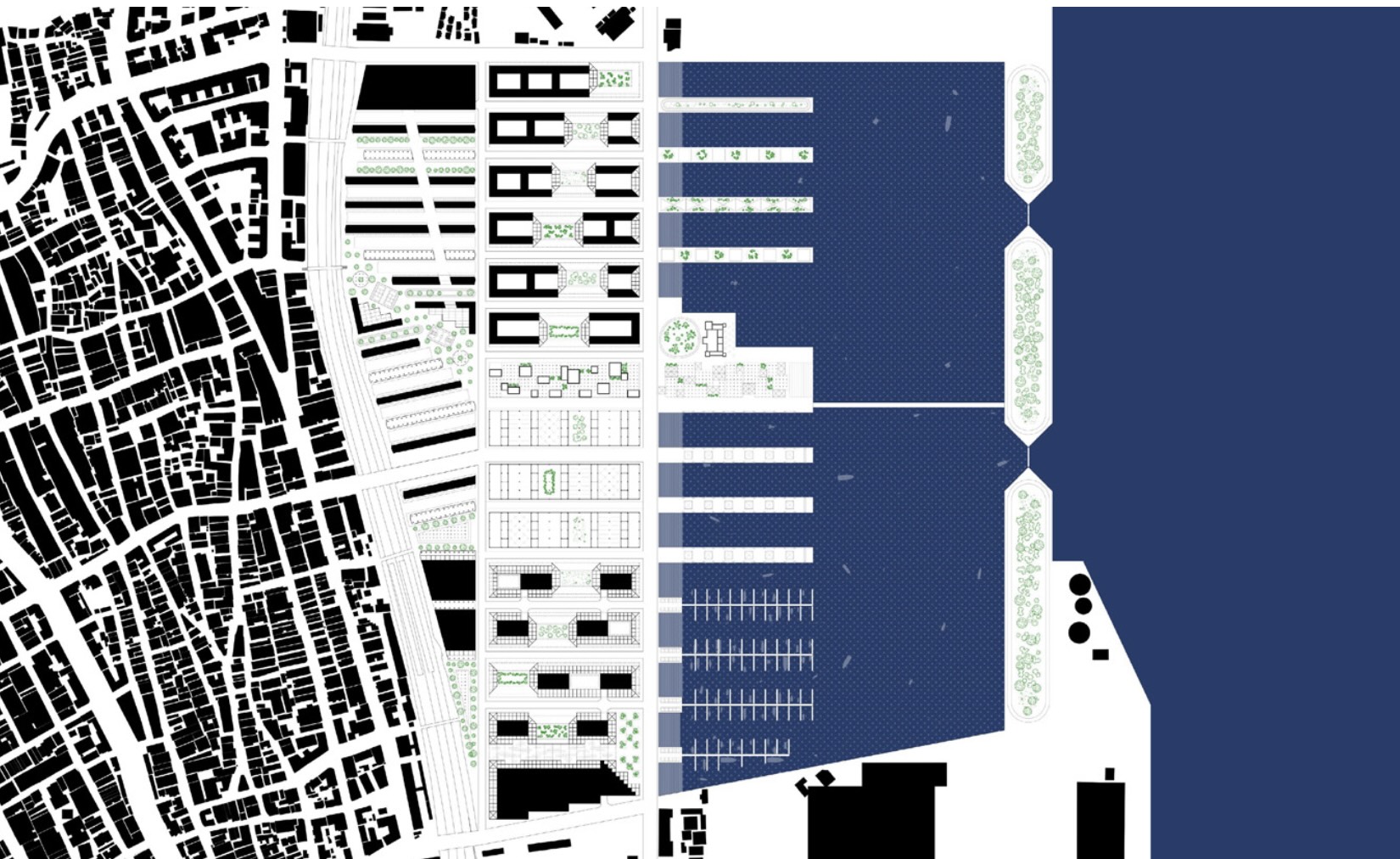

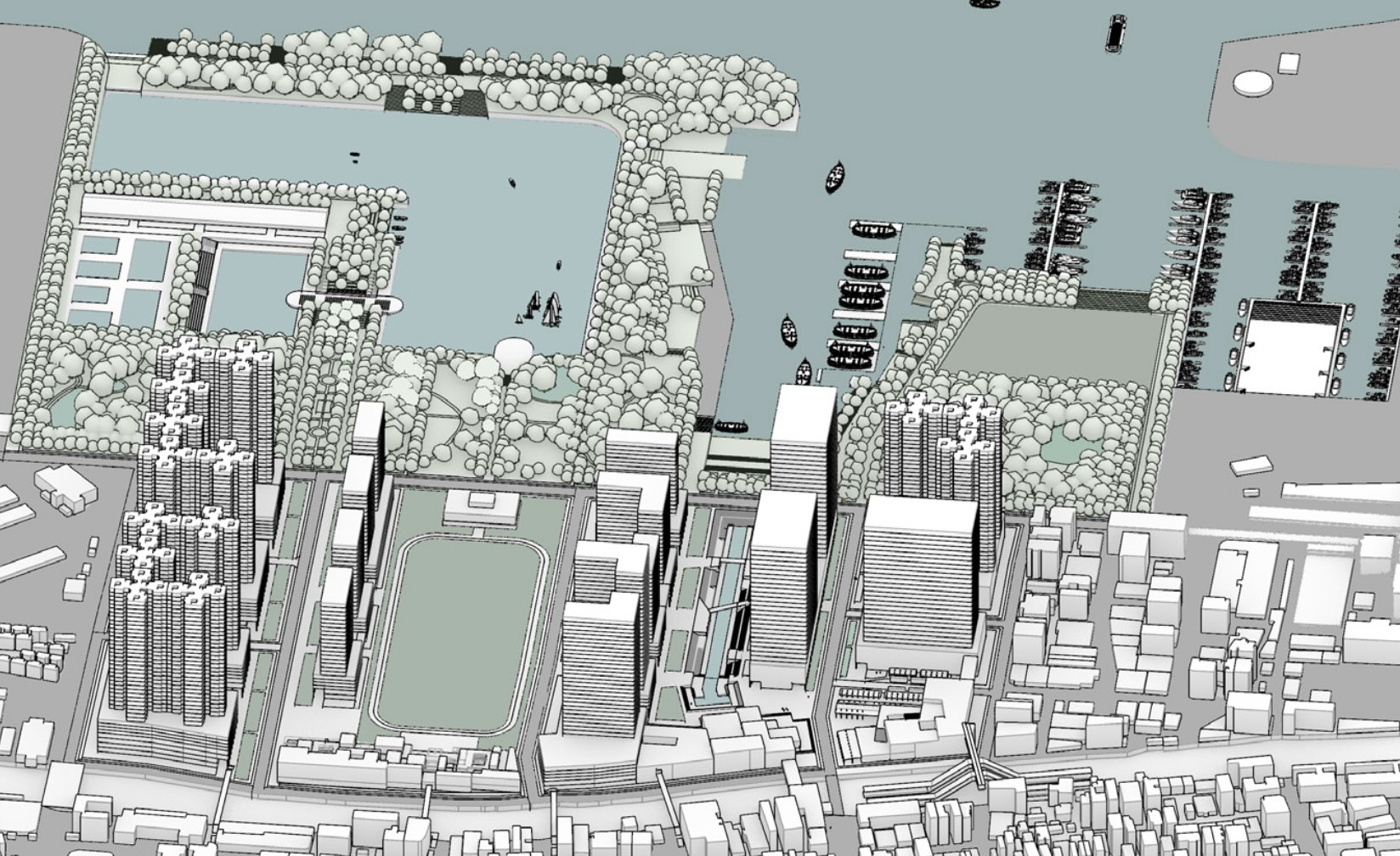

He and his classmates were introduced to Mumbai’s coastal Elphinstone Estate neighborhood and a site owned by the Port Authoritiy of Mumbai that includes 40 acres of warehouses as well as iron and steel shipping offices, bounded on one side by a rail line and on the other by the harbor and P D’Mello Road, a major city street. “The Eastern Waterfront will be one of the city’s most contested land parcels to be opened for urban development in the next few years,” writes Mehrotra. “It plays a catalytic role in connecting the city back to the metropolitan hinterland….” The 900 or so people who work in this area and live in sidewalk tenements stand to be displaced once development progresses.

Elphinstone Estate — the site of the studio

Students were tasked with working at three scales: regional, district (the “superblock”), and site (urban development policy). Rather than displacing workers whose lives are strongly rooted in the neighborhood, students were asked to invent schemes that would newly house those 900 families in tenements by “cross-subsidizing from market-value housing.” The studio offered a counterpoint to the government’s designation of the site as a commercial district. Students’ proposals served what Mehrotra terms in reference to his research, “instruments of advocacy,” creating a way to keep the city’s most vulnerable residents where they have always lived, while also offering needed market-value homes.

This studio differs from many others at the GSD, in that it involves collaboration between the studio and a Master in Real Estate course titled “The Development Project.” Jerold Kayden, Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design and founding director of the Master in Real Estate Program, and Mehrotra brainstormed about the idea of such a collaboration and launched the idea in spring 2024. David Hamilton, a real estate faculty member at the GSD, co-instructed this year’s version in the spring 2025 semester.

“I think of real estate as the physical vessel in which people live, work, and play,” Kayden explained. “And if we can apply our multidisciplinary skills and knowledge to shape real estate in ways that create a more productive, sustainable, equitable, and pleasing world, then I can’t think of a more noble cause than that.”

The magic of the combined studio and real estate class, as Kayden, Mehrotra, and Hamilton saw it, was that students from the two programs would be interdependent and could only solve the on-site housing challenges by working together. “The real estate students couldn’t own the problem because the designers didn’t design it in a way that would work in terms of real estate sense,” said Mehrotra. “And the designers couldn’t think of the design unless the real estate folks came up with a model of financing for that cross-subsidy.”

Hamilton concurred that the studio set up a collaborative tension that replicated real-world challenges: “We can imagine a path that gets us from having bright ideas and a beautiful piece of land, to a proposed future that’s both appealing and realistic enough to attract investment capital to be built. Then, we get to what we call stabilization, where the new neighborhood is working physically and financially in a sustainable way. Getting there involves a million different variables, from government action and public subsidies, to the needs of the market and investors and other financial considerations.”

Lozano saw the benefits of designing in Mumbai, where “the street is an even playing ground. Everybody takes the metro, walks the Plaza, buys street food in the markets.” At the same time, like most collaborators, his group had their share of challenges as they moved through the design process. “The entire studio was a negotiation between the students—of judging our values and understanding that the real estate students want to make a return on investment, but the subversion is the social mission, and the designers had to convince them that social space is an asset.”

He described a beautiful 19th-century clock tower on the Elphinstone site, which one of his real estate group members wanted to demolish, and how they negotiated the “iterative design process” and “pushed against the blank slate idea.” They kept the clock tower, which they saw as a cultural asset, and “turned it into an incredible public amenity with restrooms, civic spaces, and movie screenings. It’s an anchor and memory of the site itself, with the maritime history and labor organizing that occurred there.” Through the collaborative process, building trust by drawing and talking through their design plans, the design students developed a final project of which they’re proud.

“As we become surrounded by the madness and complexities of the world we inhabit,” said Mehrotra, “it’s important to have multiple perspectives on the same problem, and to synthesize those multiple perspectives into a proposition.”

The final review mirrored the lively discourse the students experienced all semester, as critics discussed the merits of each proposal and the possibilities for the Elphinstone Estate. Sujata Saunik, Chief Secretary of the Government of Maharashtra, participated throughout the final review and helped bring to the conversation a sense of Mumbai’s realities. As the student groups together advocated for shared public access to the site and investing in dignified housing for people living in tenements, they presented to the government a more equitable approach to developing a site that’s unique as well as profitable.

“It’s not the solution,” said Mehrotra, “but it’s a conversation changer.”

Student Propositions

Neeraj Bhatia’s Studio Envisions California’s High-Speed Rail as an Armature for Care

This January, the day before the Los Angeles fires ignited, California Governor Gavin Newsom announced the newest phase of construction on the long-awaited California High-Speed Rail (CHSR) from San Francisco to Los Angeles, spanning the Central Valley. Neeraj Bhatia, a design critic in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, explored with his students how the CHSR will transform the state by giving rise to what he calls a “territorial city” that “spans vast swaths of land to include both urban and rural settlements.”

Bhatia asked his fall 2024 option studio, which was sponsored by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, to consider how vulnerable populations in the Central Valley could benefit from the CHSR. The new rail system, he says, offers “an armature for accessing dispersed populations that have been underserved.” In October, the studio visited the Central Valley, with support from the Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Critics have cited failures of the CHSR such as its high price tag and long timeline, but, once completed in 2050 (as projected by the Rail Authority), riders will be able to cover the 350 miles between Los Angeles and the Bay Area in under three hours; it takes more than six hours by car and nine by conventional train. The CHSR is intended to be competitive with air travel and to help improve the environment—as well as quality of life—with less motor traffic and congestion. It will also, inevitably, change the communities connected by the system, according to Bhatia, by allowing “people to experience different cultures through living in geographies they are less familiar with, and trying to reckon with those differences to find points of empathy.”

California’s coastal cities are characterized by “scenic landscape, progressive environmental movements, and density,” Bhatia writes, “while inland California is characterized by resource harvesting and extraction, conservative values, and a depravity in social infrastructure.” Residents in the urban hubs are facing the affordable housing crisis, and, as we’ve recently witnessed in Los Angeles, worsening natural disasters. Meanwhile, with oil reserves and some of the richest soil in the world, the Central Valley’s bounty of tomatoes, lemons, peaches, walnuts, and almonds—among hundreds of other fruits and vegetables—are harvested by 55,000 migrant workers who help feed the nation.

These “two Californias”—urban and rural, progressive and conservative, dense and sprawling—a “microcosm of the United States,” have remained distanced from one another, but the CHSR will collapse their proximity, which Bhatia argues creates an opportunity to more equitably distribute resources.

Bhatia’s approach of designing to increase equity and accessibility rises out of his work as the founder of The Open Workshop in San Francisco, whose recent projects include “This Land is Your Land,” a “multi-resource cooperative” in the rapidly growing Tennessee Valley, a research proposal to provide affordable housing to diverse populations and increase broadband access. The firm’s 2021 Chicago Architectural Biennial project, “Decentering the Commune,” proposed a design for an urban commons in Bronzeville, making use of publicly owned vacant lots to provide a “network of sharing” between existing organizations, offering Chicago residents access to “food, making, ecology, and care” in ways that increase their autonomy. Finally, “Lots Will Tear Us Apart,” sited in San Francisco, a collaboration with GSD alumni Dan Spiegel and Megumi Aihara, reimagines mid-density housing typologies to “bridge lots,” catering to collective living.

In California, students had the opportunity to meet with representatives of the California High-Speed Rail Authority and visit a series of construction sites. On their return, Bhatia asked them to research a segment of the railroad, focusing on collective housing and centering opportunities for care; then, each student created their own speculative design for a station.

A Food Desert Amidst Farms

Ella Larkin (MArch ’26) and Connor Gravelle (MArch ’25) researched the Central Valley’s foodways, asking, “In a place with so much farmland, why is it so hard to get affordable, fresh produce?”

They found their answer by tracing food through the supply chain. The Central Valley harvest was first shipped to a massive consolidation center, such as those used by mass-market brand Walmart, which “aggregate goods on a territorial level before subsequent relocation to distribution centers.” Before produce reaches residents in the Central Valley, it is first shipped “upstream,” with several stops before it is transported back to a local markets, where its high price reveals the burden of its journey through a costly, time-consuming system.

Leveraging the speed of the CHSR, they designed a new system to allow fresh produce to remain in the Central Valley for longer, enabling new forms of access to residents at stops such as Kings-Tulare and Fresno.

Education on the Rail

Because educational amenities and funding are often equated to population size, people in the Central Valley face challenges in accessing educational opportunities.

Ziyang Xiong (MArch ’26) and Iam Bhunto (MAUD ’25) proposed two structures that center educational opportunities and include housing and healthcare. Finding that the Central Valley’s high school and college graduation rates are significantly lower than California’s as a whole, and that middle-skill jobs (which require more than a high school education but less than a bachelor’s) will be in demand in the coming decades, Xiong and Bhunto set out to create a new typology. To help people meet the qualifications for these jobs—for example, dental hygienist, computer technician, and EMT—they designed a “trade school with diverse and extensive shared resources,” including education centers, housing that has co-living options for students and families, and shared amenities such as a workshop and a gym.

Housing for Migrant Workers to Put Down Roots

Chloe Tsui (MArch / MDes ’27) and Inmo Kang (MArch ’25) tackled the housing shortage that the Central Valley’s migrant farmworkers face throughout the year. In the 1970s, they explained, migrant workers typically consisted of “single men who left their families behind when they traveled to California for work,” but those demographics have long since shifted.

Today, most migrant workers are “intergenerational families” who live year-round in the United States—and yet, their access to housing is limited to six-month-long rentals at state-run housing centers. Tsui and Kang found that 83 percent of families said they would remain in the homes year-round if they could; some had returned year after year for the last five to ten years.

However, to qualify, they’re required to live at least 50 miles away from the farm for a minimum of three months every year—forcing them into continual displacement. Using the CHSR, the duo provide the opportunity for migrant workers to commute across the territory, allowing them to live in one stable location while building connections and social networks. At the Bakersfield and Merced stops, they propose a series of “physical and social infrastructures for migrants,” comprised of housing cooperatives, a community kitchen, and a community center.

As more and more regions across the US plan for and construct high-speed rail systems, California will serve as an early test for what will happen to populations whose geographies have shifted due to changes in infrastructure, time, and access.

Excavating background geographies, says Bhatia, reveals what our society values. “If you want to see our relationship to energy, labor, agriculture, food—key resources that sustain us—those negotiations play out in background geographies where people also often face different forms of precarity.”

Now, as immigrants in the Central Valley face the threat of mass deportations, many too fearful to show up for work, says the California Farm Bureau, and Los Angeles grapples with the massive destruction wrought by the fires, perhaps both these polarized populations—soon to be intertwined via the CHSR—can find mutually beneficial solutions through an armature for care and equity-centered design.

Winter Reading 2025: Design Books by GSD Faculty and Alumni

In need of new reading for the new year? These recent books by Harvard Graduate School of Design faculty and alumni—published within the past six months and organized alphabetically by title—feature topics from Victorian architecture to geospatial mapping.

In Also Known As: Uncovering Representational Frameworks in Architecture, Art, and Digital Media (MIT Press, 2024), assistant professor of architecture Michelle Jaja Chang (MArch ’09) ponders relationships between objects and architecture. Drawing on design, media, computation, and art, this book employs texts and images to explore the social, material, and political impacts of architectural systems and design technology.

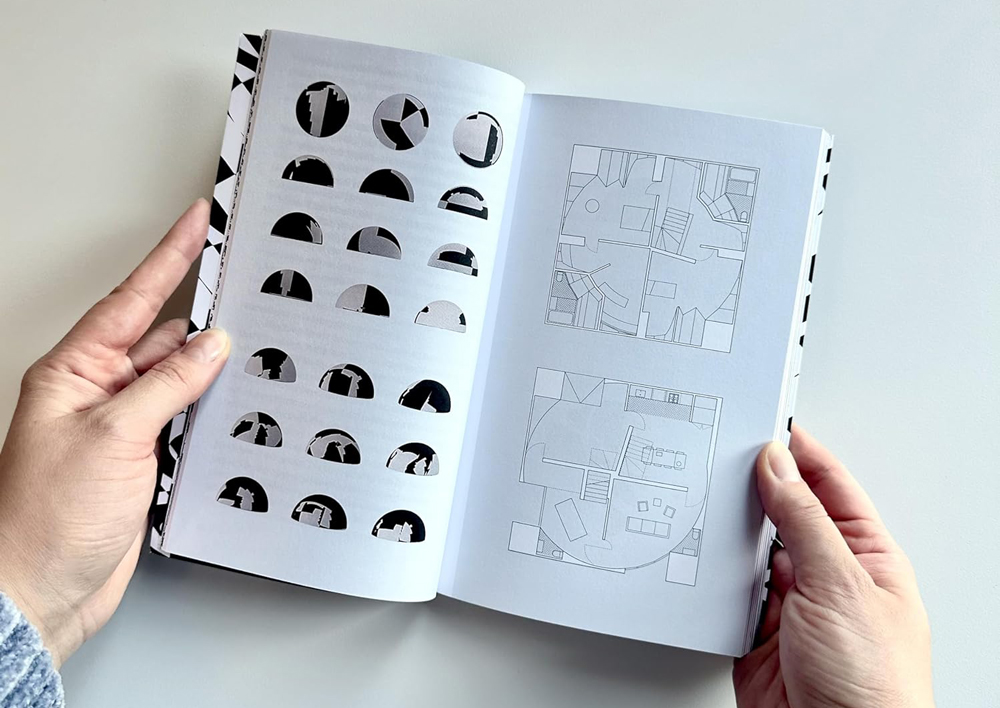

A contemporary architectural manual, The Architect’s Sourcebook: Dimensions and Files for Space Design (Birkhäuser, 2024), written by Stanley Chaillou (MArch ’19), presents a digital repository of typologies, from housing to work to leisure spaces, complete with explanatory texts, general dimensions and guidelines for 2D layouts, and downloadable CAD blocks.

Architecture.Research.Office. (DelMonico Books, 2024), edited by Stephen Cassell (MArch ’92), Kim Yao, and Adam Yarinsky, documents over thirty projects by the editors’ New York–based firm Architecture Research Office (ARO), recipient of the American Institute of Architects Firm Award in 2020. Founded in 1993, ARO is known for engaging, research-driven projects with a clean aesthetic, including the phased renewal of the Rothko Chapel and Campus (ongoing) in Houston; the Brooklyn Bridge Park Boathouse (2018); and the Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (2016) in New York City.

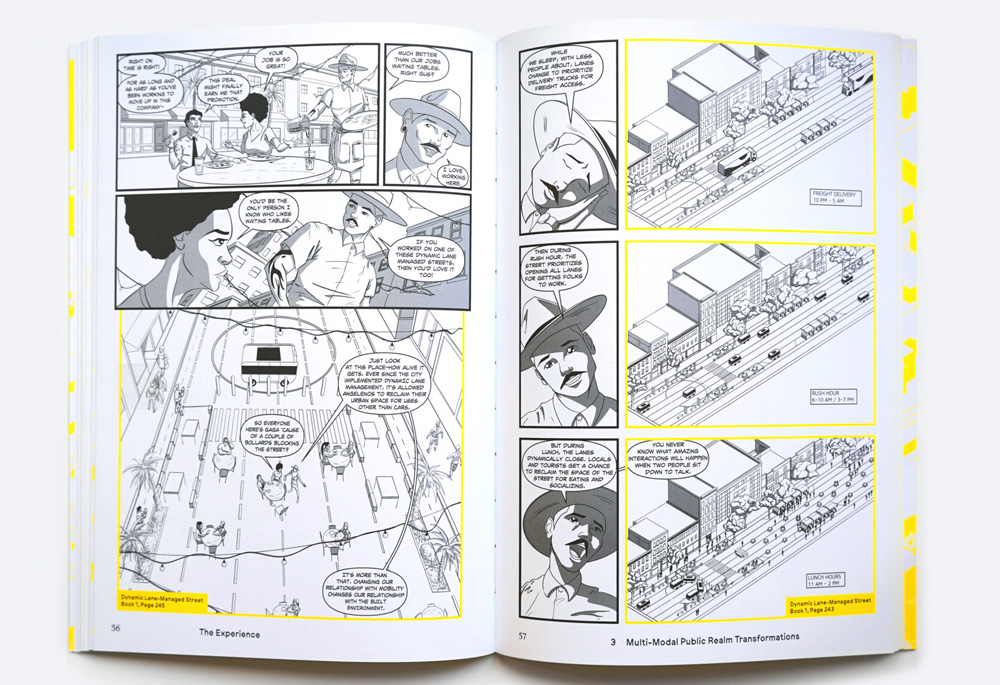

Autonomous Urbanism: Towards a New Transitopia (Applied Research + Design Publishing, 2024), by Evan Shieh (MAUD ’19), explores the latent and transformative impact autonomous vehicles will have on the urban and spatial future of cities. Employing representational techniques of graphic novels, the book explores our recent history of urban transportation and speculates on the typologies and policies that await us with a driverless mobility paradigm shift.

In “Modernism in Three Acts,” published in editor Léa Namer’s Chacarita Moderna: La Nécropole Brutaliste de Buenos Aires (Building Books, 2024), associate professor of architecture Ana María León (MDes ’01) draws on archival documents held at the Special Collections of Frances Loeb Library to explore the architectural context in which Argentine architect Ítala Fulvia Villa designed the monumental Sexto Panteón (Sixth Pantheon) at the Chacarita Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Juxtaposing an essay by Mohsen Mostafavi, Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Professor, with one written decades prior by the German art historian Max Raphael (1889–1952), The Color Black: Antinomies of a Color in Architecture and Art (Mack Books, 2024) expounds on the relationship between architecture, art, and the color black. Commentary by Swiss architect Peter Märkli and American artist Theaster Gates, along with a broad range of illustrations, offer additional thoughts on contemporary architectural and artistic developments.

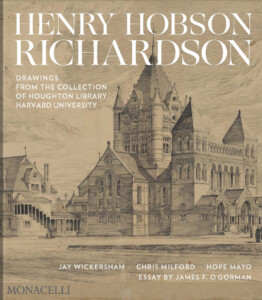

Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University (Monacelli, 2024), by Jay Wickersham (MArch ’84), Chris Milford, and Hope Mayo, presents previously unpublished sketches, renderings, and plans of more than 50 projects by the famed nineteenth-century architect, covering building types from houses and railroad stations to churches, libraries, and civic structures. Essays by the authors as well as architectural historian James O’Gorman shed light on Richardson’s extensive oeuvre and enduring legacy.

With IDEAS–A Secret Weapon for Business: Think and Collaborate Like a Designer (Routledge, 2024), Andrew Pressman (MDes ’94) offers a sensible guide for leaders to incorporate elements of design thinking within their organizations. Relying on case studies and practical techniques for fostering creativity and critical thought, this book provides readers with a framework to encourage innovation and teamwork in all business realms.

Large, Lasting, & Inevitable (Park Books, 2025) by Jorge Silvetti, Nelson Robinson Jr. Professor of Architecture, Emeritus, illuminates foundational moments that have shaped architectural thought throughout the past six decades. Edited by Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch II ’20), the book features a selection of Silvetti’s seminal texts alongside discussions with figures of the next generation—including design critic in architecture Mark Lee (MArch ’95), Robert P. Hubbard Professor of Architectural History Erika Naginski, Elisa Silva (MArch ’02), Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), and Alfredo Thiermann.

Meet Me at the Library: A Place to Foster Social Connection and Promote Democracy (Island Press, 2024), by Shamichael Hallman (LF ’23), positions libraries as spaces that, when properly conceived and programmed, help build inclusivity communities. Drawing on extensive research and examples from throughout the United States, Hallman highlights the significant role libraries could play in healing the rifts that divide our nation.

Monumental Affairs_Living with Contested Spaces (Hatje Cantz, 2024), edited by Germane Barnes (Wheelwright Fellow, ’21), presents interviews, lectures, and other documentation from the Design Akademie Saaleck’s 2023 symposium, held at the former home of National Socialist ideologue and architect Paul Schultze-Naumberg in Saaleck, Germany. The most recent installment in the dieDASdocs series, this text features interdisciplinary explorations into discriminatory architectural and urban practices embedded within the conception, production, and endurance of monuments.

To Nos Lieux Communs (Fayard, 2024), edited by Fabrice Argounès, Michel Bussi, and Martine Drozdz, assistant professor of urban planning Magda Maaoui contributed a discussion on the Haussmannian “chambre de bonne” worker housing typology at the intersection of historic preservation, climate adaptation, thermal comfort, and health. An essay by Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology, addresses the complex global geographies of data centers.

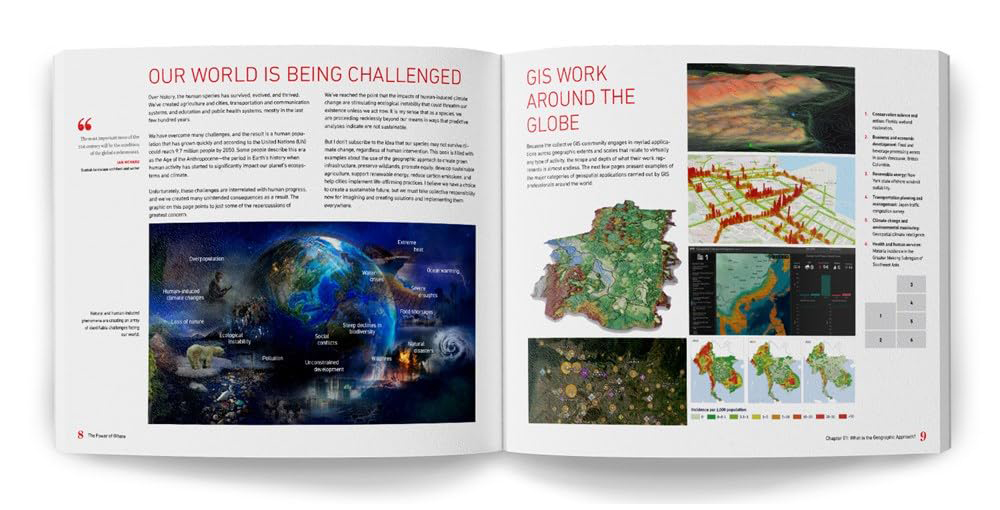

In The Power of Where (Esri Press, 2024), Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69) details the history and advancements of geographic information systems (GIS), presenting mapping as a problem-solving method that allows users to perceive and understanding patterns of all kinds—from spatial to environmental to demographic. Architect and designer Richard Saul Wurman described the richly illustrated book as “a bible of the types of maps, cartography, spatial analysis, and diagrams that can bring our ideas for the future to life.”

Radical Atlas of Ferguson, USA (Belt/Arcadia Publishing, 2024), by Patty Heyda (MArch ’00), probes the planning policies that shaped the St. Louis suburb where, in 2014, racial tensions erupted following the murder of 18-year-old Michael Brown. Using more than 100 maps, Heyda examines philosophical, financial, and design-related forces that set the stage for this violence, prompting readers to consider for whom cities are built and how design impacts everyday life.

Revitalizing Japan: Architecture, Urbanization, and Degrowth (Actar Publishers, 2024) features the work of young architects in Japan who are practicing in ways that respond to the post-growth condition of the country’s shrinking population. Co-edited by Kayato Ota and Mohsen Mostafavi, Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design and Harvard University Distinguished Professor, the book contains texts by architect Toyo Ito and community designer Ryo Yamazaki and photos by Kenta Hasegawa

An Interview with Richard Sennett: Democracy and Urban Form

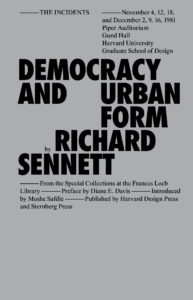

In fall 1981, the eminent sociologist and urban theorist Richard Sennett delivered six public lectures at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), focused on ways in which the city’s spatial characteristics can foster—or forestall—democracy. This month, more than 40 years after the lectures’ original debut, Harvard Design Press and Sternberg Press published them as Democracy and Urban Form . In the book’s preface, Diane Davis, Charles Dyer Norton Professor of Regional Planning and Urbanism at the GSD, notes that despite the lectures’ age, they maintain relevance, inspiring designers “to think ethically, critically, and responsibly about which kinds of cities and societies they could be producing if they understood how individuals and groups relate to the spaces that they as professionals are designing.”

Harvard GSD’s Krista Sykes talked with Sennett about the evolution of his thoughts on urbanism, the need to take architecture seriously, and the fundamental importance of encountering others unlike oneself. Their interview followed a series of talks and panel discussions held at the GSD in October to celebrate the publication of Democracy and Urban Form.

Krista Sykes: Many concepts from your 1981 lectures hold true today; at the same time, your thoughts appear to have shifted in some ways. For example, during the panel you stated that, in recent decades, you have become more interested in “the mobilizing power of architecture,” which I understand as architecture’s potential to shape human interactions, rather than in its representative or symbolic abilities. What motivated this shift?

Richard Sennett: A couple of things. After I left the United States in the late 1990s, I went to the London School of Economics [LSE] and set up an architecture and urban studies program with Richard Burdett. This program was orientated to practical solutions to problems in Britain. It was a new country for me, and the notion of actually problem-solving—that’s the DNA of the LSE—got me thinking about what architecture could solve in a practical way for problems about economic inequality and so on. Yet, I also was very resistant to that because I think that architecture should be visionary rather than pragmatic. And I began to experience this as a very useful contradiction. My impulse was to say, “let’s think about what might be.” My colleagues at the LSE were thinking, “well, what do we do next? The government has asked us to solve this problem next year.” That stimulated me to think more about mobilizing our architecture.

A second aspect that made me believe in this: I was very struck in Britain that younger architects had lost faith in architecture. They thought it was only a representation of social and economic conditions. That seemed to me very sad—a very sad take on a profession which you think is merely the puppet of the social order. And although I’m trained as a sociologist, I don’t think sociology has that kind of power over the imagination, particularly of people who know how to practice an art.

Yet another thing that really got me going about the mobilizing power of architecture was that I worked for the United Nations for 10 years. In poor countries like Mali or Ghana, it was hard to maintain that the way things are built has nothing to do with the way in which people live. When you’re in a country in which there aren’t enough schools to go around, thinking about what a school should look like is part and parcel of being with a scarcity of resources; it’s not something separable from it. Certainly, the people that I worked with in Sub-Saharan Africa and also in the Far East didn’t see a divide between the expressive qualities of architecture and its practical qualities. That’s a distinction that happens in more privileged societies.

I was reminded of this a few months ago. We have a housing shortage in Britain, and a top housing official declared she didn’t want to build something that was beautiful. She wanted to build something that served a practical need. Only in a very spoiled, rich country could you draw the distinction between quality and quantity. That’s how I came to be much more interested in the qualities of how things look, the qualities of architecture that are of social value.

Likewise, in your 1981 lectures, you emphasize how cities foster democracy by facilitating discourse. Today, your focus is more on bodily presence—what you have referred to as the “democracy of the body.” What prompted this turn?

Well, I think part of the reason that a lot of young architects that I was teaching in London had lost faith in architecture was because they looked at architecture as a discursive practice. It isn’t. Certainly, the political aspects of democracy are as much physical and nonverbal as they are verbal. We always think about democratic form in terms of discourse, and that seems very limited to me. So, I gave a course one year, a research seminar called “What is a Democratic Door?” Originally, people thought this was a joke. But after three months, I had woken them to the notion that, yes, you can embody democracy in the form of a door. It was part of the same shift of taking architecture more seriously.

Perhaps architecture embodies greater power when the focus is on bodily presence instead of discourse, taking a person’s willingness to verbally interact out of the equation. People are exposed to difference simply by occupying a given space with others.

Oftentimes, people will embody a practice that they can’t or wouldn’t explain. It’s true about all aspects of life, that people do things which they are not consciously masterminding. That’s certainly true about the relations between people in social space, in physical space. An assembly line can be racially mixed, yet the people working on it aren’t thinking about what racial integration is. They’re just working together. That’s another aspect of this same shift; it’s too great a burden on people to explain what they’re doing as though the actions that they’re taking are consequences of conscious decisions. There’s a whole issue about democratic theory: often we act on knowledge which is not fully articulated to our self.

How does this translate to environments that lack the density and diversity for such exposure to difference? I’m thinking about the current political divide and our pending presidential election. How might we promote democracy outside of urban situations?

I’m quite worried about this. I mean, there’s no reason why people can do things unconsciously that are bad for them. When you look at Trump’s audiences, they’re all old, or mostly old, and they’re mostly white. I’m not sure those rallies could have actually worked if there were significant numbers of Black people or significant numbers of kids.

I had one of my students examine one of these rallies to take a reading on how old people were and how racially mixed they were. As you can imagine, up in the front near Trump’s rostrum, about five or six rows deep, it’s all mixed. When you get behind that, it’s a sea of whiteness, and it’s a sea of people who are, like me, going bald. My sense of it is that, if these are people who don’t have much daily physical experience being with people unlike themselves, that lack of physical interacting with people unlike oneself can easily lead to fantasies about the other, about who they are. That’s part of what we are facing. There are lots of studies showing that the more racial mixing you have in workplaces, the less racial prejudice is felt on both sides of the divide.

This dovetails with my final question. The 1981 lectures underscore the need to expose people to difference as a democratic undertaking because it allows them to understand themselves as one among many. You describe this experience as one of solitude. “In modern cities,” you stated, “we’regoing to have to come to terms with this new order of solitude.” How might you reposition this experience for the present day?

Well, the ultimate form of solitude that people are experiencing now is online. There’s an editing out of anything that people don’t want to hear. Online you’re in an echo chamber, essentially. That takes us back to the physical city where you have experiences in which you can’t just push a button and withdraw from other people. This has an old history. One of the reasons that politically conservative people don’t like to use public transport is because, involuntarily, there are people on buses or subways who are not like them. It’s a well-known sociological phenomenon. That’s why a lot of Americans like cars, because they’re like an isolation booth. And online has become an evolution of the that. You’re a button away from withdrawing, from being exposed to people unlike yourself.

That’s why physical space is so important. I think for architects, we’ve got to find ways in designing schools or hospitals to mix people up more. When I worked in Mali on a hospital where we mixed up urban lower- and middle-class people using the hospital with people who were agricultural workers, shepherds, and such, it was resisted at first by both groups. And we mixed up men and women as well, which was resisted. But in the end, it made the hospital more of a communal experience.

We have to think out of the box about this. That’s why I’m a great believer in bussing, and not a believer so much in homogenous local communities. That’s why a lot of the planning work I’ve done has looked at the edges, at how do you bring the edges between communities or different sections of the city alive—which I think of as democratic, with the edges being more democratic than the center. But that’s a whole other story.

Contemporary Memorials: Spaces of Engagement, Calls to Action

As Christopher Columbus plunged into Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, and General Robert E. Lee dismounted his pedestal in Richmond, a distinctive kind of memorial has been gaining traction.1 While past debates centered on a memorial’s formal qualities—figurative or abstract?—attention has pivoted from aesthetic attributes to the ways in which a visitor interacts with a memorial. Rather than an object to be contemplated, today’s memorial is a space to be experienced. And with this shift from contemplation to experience, a focus driven in part by faculty and alumni of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), comes an emphasis on active engagement, now and in the future.

Take, for example, the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers (MEL), which swells from the lawn just east of the Rotunda on the University of Virginia’s (UVA’s) campus. Designed by Höweler + Yoon, a firm founded by GSD professor of architecture Eric Höweler and dean of Cornell University’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning J. Meejin Yoon, who graduated from the GSD in 1997, this installation honors the 4,000 enslaved individuals who built and worked at the university from its inception in 1817 through the Civil War’s conclusion nearly 50 years later. Composed of concentric granite rings, the outermost cresting to 8 feet in height, the memorial beckons to passersby traversing campus and across the street in Charlottesville. On the larger ring’s smooth inner wall they find inscribed 578 names and 311 phrases of kinship or occupation, such as “daughter” or “mason,” along with more than 3000 “memory marks”—placeholders for the yet-unidentified enslaved individuals. Visitors also encounter a timeline, awash with water, that denotes the racial violence underlying Jefferson’s “Academical Village.” These features partially enclose a circle of grass, a public space for meeting and interaction, recalling clearings in the woods where enslaved people would secretly gather. Meanwhile, in certain light conditions an ethereal portrait of Isabella Gibbons—a former enslaved domestic worker at UVA who became a Charlottesville school teacher—materializes on the MEL’s outer wall, suggesting that the history of which the memorial speaks is ever present, even when unseen.

Dedicated in 2021, the MEL is a contemporary memorial in date and sensibility: it engages visitors in an active manner, through multiple and flexible means; it contains room for emergent information (new names can be inscribed); and it incorporates input from a range of stakeholders, including UVA students and descendants of the honored individuals, who took part in its conceptualization. The MEL aspires to more than the commemoration of a person, group, or event; it sheds light on a previously suppressed history—not as a closed episode, but rather as an ongoing collective conversation in the present and future. “Righting past wrongs is what we were asked to do,” noted Höweler, who with Brenda Tindal was recently appointed co-chair of Harvard’s Legacy of Slavery Memorial Project . “How do you begin repair in the present by starting with the past and being more truthful about it?”2

A reflection of changing attitudes toward memorialization, in 2016 the National Park Service, National Capital Planning Commission, and Van Alen Institute co-sponsored Memorials for the Future , “an ideas competition to reimagine how we think about, feel, and experience memorials.”3 After analyzing the 89 submissions drawn from around the world, the organizers issued Not Set in Stone , a document underscoring potential key aspects of memorial design moving forward. The overarching message highlights the heterogeneous audiences that today’s memorials address as well as the inherent complexity and multi-dimensionality memorials now embody. The report offers broad guidelines for thinking about new memorials, recommending that they engage with the present and future as much as the past; accommodate shifting narratives; harness public involvement for conceptualization; and explore mobile or temporary forms of expression.4 The winning submission for Memorials for the Future, Climate Chronograph by landscape architects Rebecca Sunter and Erik Jensen, exemplifies these ideas, repurposing a portion of East Potomac Park in Washington, DC, as a place for visitors to kayak among the dead cherry trees, left behind as persistent sea level rise subsumes the land.5

Throughout the past decade, elements espoused by Not Set in Stone have appeared with increasing frequency in new memorials, as evidenced through a brief survey of projects by Harvard GSD affiliates—including those responsible for the MEL. Höweler + Yoon also designed the Collier Memorial (2015), sited on Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s campus where Officer Sean Collier was shot and killed following the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013. Comprising 32 blocks of granite that create a five-way stone vault, the memorial serves as an iconic destination, mid-campus passageway, and dynamic sculptural presence, its form suggesting that strength derives from unity.

The notion that contemporary memorials are “more visitor-centric”—less about observation and more about interaction—aligns with the recent competition-winning design for the Fallen Journalists Memorial (FJM) by Chicago-based architect John Ronan, who graduated from the GSD in 1995.6 Located on the National Mall in Washington, DC, and slated for completion in 2028, the FJM serves a twofold purpose: to honor journalists who have died in the pursuit of truth, and to educate visitors about the First Amendment’s role in a democratic society. With the FJM still working its way through the federal approval process, images of the design have not been released. Yet it has been revealed that Ronan’s design employs an array of glass elements through which visitors navigate to reach a “place of remembrance,” echoing the investigative journalist’s “journey of discovery” as a story comes together.7 The FJM thus distinguishes itself within its monument-saturated landscape by demanding the visitor’s active engagement.

A prerequisite of active engagement likewise informs Penjing , the shortlisted project for the Memorial to the Victims of the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871 by GSD alumni J. Roc Jih, James Leng, and Jennifer Ly (who graduated in 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively). Nearly 150 years ago, a racist mob terrorized and lynched 18 Chinese men. The incident, which precipitated anti-Asian laws that restricted Chinese immigration, remained largely unacknowledged until 2021, when Los Angeles and California allocated funds for the commemoration of the massacre. In response to a call for submissions, Jih (of Studio J. Jih in Boston) and Leng and Ly (of San Francisco-based Figure) crafted a design that unites the Chinese concepts of Pen (frame) and Jing (scene) in a series of multitextured limestone vessels that house miniature gardens and mark locations in downtown Los Angeles significant to the massacre. The designers envisioned the installations as living sculptures to be cultivated by residents, who encounter the gardens as they move through the neighborhood; inscriptions on the ground educate visitors, ensuring that the massacre remains part of the public discourse. As Jih noted, “We see remembrance as a constant and ongoing act rather than as something sacred and unchanging.” Through the incorporation of living elements, “the act of remembering also becomes one of care and maintenance, inviting tactile engagement.”8

Likewise, visitor engagement figured prominently in the conceptualization of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (2018), created by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). Following years in-depth research on lynching and the lasting impacts of racial violence, EJI collaborated with an array of designers and artists to construct, across a six-acre site adjacent to the State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, a memorial that honors the more than 4,400 victims of racial terror lynchings that took place in the United States between 1877 and 1950. MASS Design Group, founded by Michael Murphy and Alan Ricks (GSD graduates from 2011 and 2010, respectively), worked with EJI on one of the memorial’s elements of the memorial: a pavilion that contains 800 suspended steel columns —one for each of the counties in which a lynching took place—engraved with victims’ names.

A passageway descends through the columns, with visitors journeying to a position below, gazing up as if part of the crowd at a public lynching. Surrounding the pavilion, matching columns wait for their respective counties to claim and transport them home. In this way, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice engages more than its immediate visitors, extending its reach to hundreds of counties that must choose to create local memorials, thereby acknowledging their past atrocities, or leave the columns in Montgomery, signaling their lack of remorse. The National Lynching Memorial thus acts as a tool for engagement, education, and public accountability.

In 2019, the Gun Violence Memorial Project , designed by MASS Design Group and Songha & Company, where artist Hank Willis Thomas is creative director, debuted at the Chicago Architecture Biennal before opening, in spring 2021, for a two-year run at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC. As explained by Jha D. Amazi, principal at MASS Design Group, the memorial aims “to communicate the enormity of the [gun violence] epidemic while also honoring the individuals whose lives have been taken.”9 The design features four houses composed of 700 transparent glass bricks, with each house signifying the weekly human cost—700 lives on average—of gun violence in this country.10 Families who have lost someone to gun violence have donated remembrance objects from drivers’ licenses to Double Dutch jump ropes, which are displayed within a glass brick along with the victim’s name, date of birth, and date of death. For visitors, these objects humanize the victim, transforming them from a statistic to a person. Additional engaging elements include audio and film clips about the effects of gun violence, which visitors experience as they enter the houses to view their contents.

For the families of victims, the remembrance objects act as visible tributes to their loved ones. Simultaneously, the objects encourage interaction between the families as well as society at large. This begins with the objects’ process of collection, which draws families to given places at designated times; indeed, since opening five years ago, representatives from the Gun Violence Memorial Project have traveled to 14 cities around the country, holding collection events to fill formerly empty glass bricks. At these events, families encounter, and ideally connect with, others in their area who suffer with gun-violence-related tragedies. Then, once the objects populate the glass bricks, the families by default join the memorial’s contributory community—not a formal designation, yet nonetheless meaningful. Finally, the objects connect families with people they may never meet yet who, by experiencing the memorial, will be touched by these individual stories. The Gun Violence Memorial Project, fortified by the assembled remembrance objects, underscores the vast reach of gun violence, a nationwide epidemic the United States has yet to sufficiently accept or address.

In late August 2024, the Gun Violence Memorial Project opened in Boston. As opposed to its tenures in Chicago and Washington, DC, the memorial’s current manifestation involves a citywide collaboration, with displays at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston City Hall, and the MASS Design Group’s gallery. With this shift from a single venue to multiple sites throughout a city, the memorial appears to have leapt in scale, taking a great stride toward its ambition to “foster a national healing process that begins with a recognition of the collective loss and its impact on society.”11 Unlike static monuments that were conceived to be seen, this contemporary memorial elicits interaction and active engagement. As the Gun Violence Memorial Project illustrates, such a memorial can even be transitory; what persists is the human experience it provides.

*This piece was updated to describe the Equal Justice Initiative as the originator of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

- Rachel Treisman, “Baltimore Protesters Topple Columbus Statue,” NPR, July 5, 2020; and Whittney Evans and David Streever, “Virginia’s Massive Robert E. Lee Statue Has Been Removed,” NPR, Sept. 8, 2021. ↩︎

- Eric Höweler, interview with author, June 27, 2024. ↩︎

- Not Set in Stone (National Park Service, National Capital Planning Commission, and Van Alen Institute, 2016), 2. ↩︎

- “Key Findings,” Memorials for the Future, Van Alen Institute. ↩︎

- “Competition Winner,” Memorials for the Future, Van Alen Institute. ↩︎

- John Ronan, interview with author, Mar. 25, 2024. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Penjing,” Work, Studio J. Jih.. ↩︎

- Jha D. Amazi, “The Gun Violence Memorial Project,” Exhibitions, Institute of Contemporary Art. ↩︎

- This average number of 700 gun deaths per week in the United States is based on a statistic from 2018. As of May 2024, the average number of gun deaths per week for the year is 840. ↩︎

- “About,” The Gun Violence Memorial Project. ↩︎

Project Spotlight: UPD Site Visits

“We strongly believed that a deeper level of engagement with community-based organizations could provide us with more comprehensive insights. We knew it would enrich our coursework by connecting theory with real-world implementation.”

– Abdul-Razak Zachariah MUP ’23

Abdul-Razak Zachariah MUP ’23 and Lamei Zhang MUP ’23 met during their first year at the GSD in core studio. The two hit it off immediately, bonding over their similar backgrounds working with nonprofits and a shared desire to fight systemic inequities through design. As their academic studies presented contemporary and historical design challenges around the world, they saw an opportunity to bring their learning in the classroom to the communities closest to them.

Abdul: “So many of the GSD studios take place across the country or overseas. In contrast, there were barely any opportunities to work with the communities closest to us. It felt like there was a gap in the curriculum.”

Abdul and Lamei began the process of planning their student-led field trips, the Urban Planning Design (UPD) Site Visits. They chose a number of local neighborhoods in the Greater Boston area, including places like Chelsea, Dorchester, Chinatown, and Roxbury. They understood that many people in their cohort were not familiar with issues of systematic racial inequity, so they took it upon themselves to increase awareness and knowledge among their peers through these site visits, helping inform their future roles as planners and designers.

Lamei: “We found it crucial to explore the connection between communities of color, young people of color, and urban planning. We wanted to find ways to better ensure that urban planners and designers understood the voices and experiences of these communities in their training and future professional practice.”

While planning their site visits, Abdul and Lamei had the idea of reaching out to local organizations, including the Asian Community Development Corporation, the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, DREAM Collaborative, and GreenRoots, among others. They were thrilled by the idea of learning directly from community partners that were already implementing the concepts they were studying in their coursework—community land trusts, housing development models, and the integration of climate considerations into city planning.

Their fieldwork spanned the greater Boston area and prioritized small group visits, during which they explored organizations’ offices and projects and discussed their processes and challenges. Many discussions emphasized the significance of history, planning, and design. Abdul and Lamei aimed to convey to their peers that they could actively contribute to creating positive change as planners and designers regardless of their background in and familiarity with these fields. This included time spent in debriefing sessions that provided students time to do valuable internal work through reciprocal sharing and reflection.

Lamei: “We wanted to thoughtfully engage with community organizations to learn about the historical context that played a role in shaping current neighborhood situations. Understanding the unique characteristics and significance of each neighborhood became a cornerstone of our work.”

After receiving a grant from the Racial Equity and Anti-Racism (REA) Fund, Abdul and Lamei were able to compensate the organizations that they worked with during each site visit, as well as help cover transportation costs and funding for debrief sessions—ensuring that the visits were accessible to students interested in attending.

Additionally, the funding has allowed the program to be available for future UPD students. This past year, the Harvard Urban Planning Organization, a student-run group, provided additional financial support for the program, and during the spring of 2023, the Department of Urban Planning and Design explored adopting the UPD Site Visits as a department-supported initiative.

Abdul: “We can’t stress enough how important ongoing student advocacy is to ensuring that these initiatives not only come to fruition, but also thrive. With the Master in Urban Planning program being two years long, maintaining continuity becomes a real concern. We truly believe that our efforts can spark and have sparked transformative change, and we’re hopeful to attract more alumni and donors who share our vision.”

The REA Fund provides grants for select student and faculty projects that analyze the historical complicity of design in constructing systems of inequality. This funding is made possible, in part, through annual giving.

Learn more about annual giving and its impact at the GSD here.

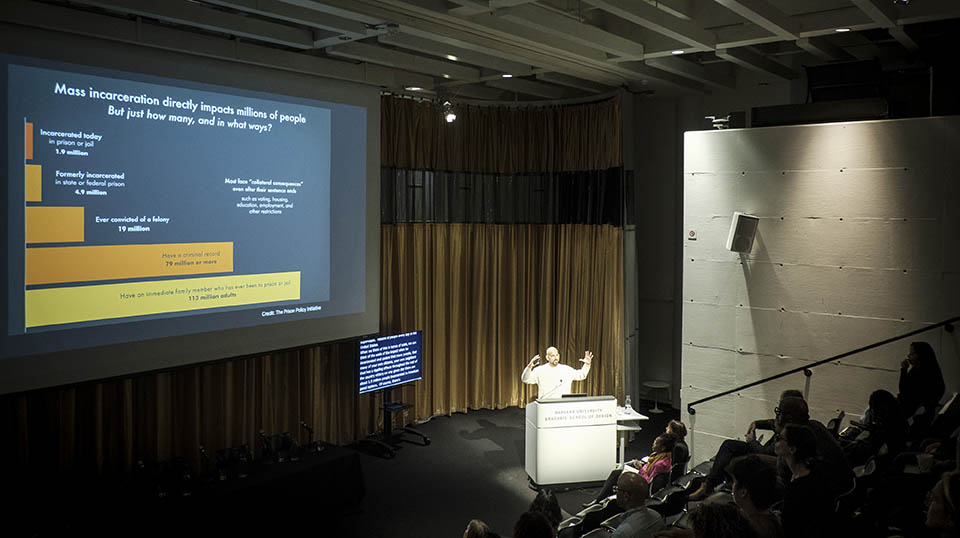

“A Radical Obvious Idea”: “Carceral Landscapes” Confronts the Role of Design in Mass Incarceration

A photograph from the 1950s depicts Chicago’s Cook County Jail in a fragile state. An imposing wall had crumbled, leaving bricks—many of which were produced by inmates themselves—scattered in the yard. Melanie Newport , Associate Professor of History at the University of Connecticut, shared the image as part of “Carceral Landscapes,” a symposium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in October that aimed to foreground the role of architects, designers, and planners in confronting mass incarceration in the United States. The photo of the jail in ruins served as an evocative touchstone for discussion throughout the event. Speakers and audience members alike reflected on the imposing facilities designed by architects to detain millions of people as well as the effort required to unmake that architecture.