Khao Yai Art Forest is a spectacular 120-acre site several hours northeast of Bangkok. Opened in 2025, it offers visitors singular opportunities for aesthetic contemplation, with works by renowned artists including Louise Bourgeois, Richard Long, and Fujiko Nakaya set within a lush, mountainous landscape.

For Marisa Chearavanont, who initiated the project, the Art Forest is as much about caring for the land as it is about displaying contemporary art. Delivering the keynote address at the conference “Designers of Mountain and Water: Alternative Landscapes for a Changing Climate” at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), she described a formative source of inspiration: a traditional ink landscape painting—an example of sansuhwa—displayed in her childhood home in Korea. Depicting stable mountains and flowing water, the painting embodied an intricate balance that Chearavanont hoped to recover through the Art Forest.

Although situated near one of Thailand’s national parks, the site had once fallen into poor condition. Natural forests were depleted, and the soil degraded by tapioca farming. Chearavanont described the area’s transformation over recent years as an “ecosystem regaining its dignity.” Landscape architects at Bangkok-based P Landscape , founded by Wannaporn Pui Phornprapha (MLA ’95), led a rejuvenation process that she characterized as “discovering what the land wants to become.”

Her keynote set a personal and poetic tone for a conference that brought together scholars and practitioners for a wide-ranging discussion on the history and future of landscape design in Asia. Organized by Jungyoon Kim, associate professor in landscape architecture at the GSD, and Nicholas Harkness

, Modern Korean Economy and Society Professor of Anthropology and director of the Korea Institute at Harvard University

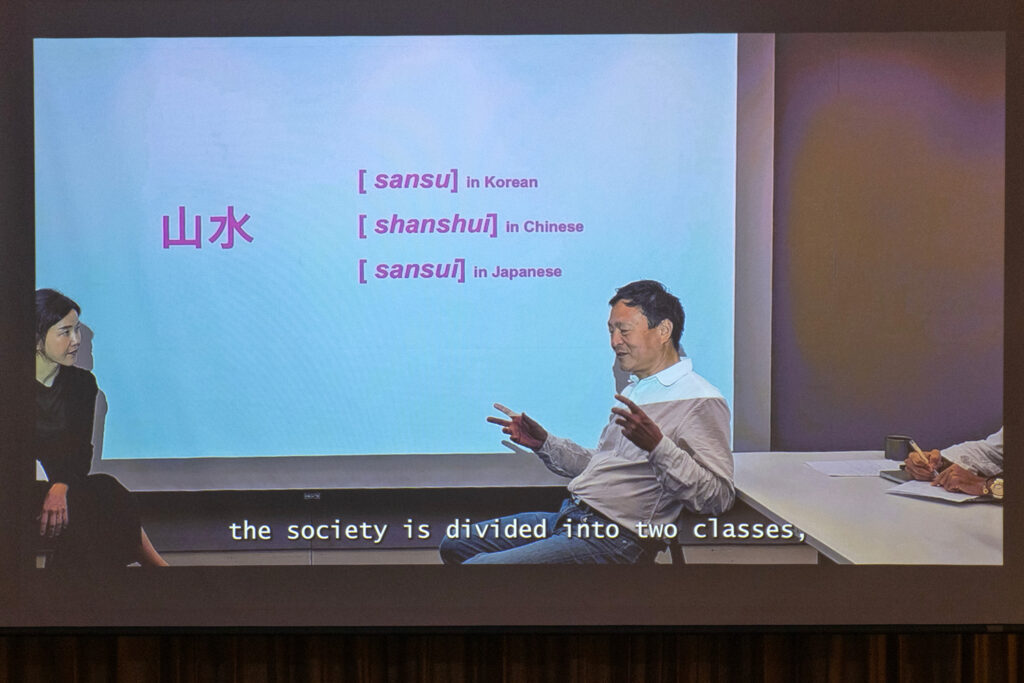

, the conference took as its point of departure the Sinographic compound 山水—literally “mountain and water.” The term conveys a nuanced aesthetic and philosophical understanding of the natural world, one with deep roots across East Asia as sansu in Korea, sansui in Japan, and shanshui in China.

Full recordings of the conference presentations are available on the event page.

Despite this long cultural history, the modern profession of landscape architecture is relatively new in the region, as Kim noted in her opening remarks. Seeking to “explain Asian landscape architecture from its own context,” she conducted extensive research with GSD students, culminating in an exhibition on view in the Druker Design Gallery through May. The exhibition features 58 projects, including Khao Yai Art Forest, and highlights work that is “legible as system, process, and method”—projects that respond directly to ecological conditions.

To underscore how designers engage natural parameters, Kim organized the exhibition according to bioregions rather than national borders. Defined by ecology, climate, and geology—“the borders that nature drew”—these bioregions follow classifications standardized by the environmental nonprofit One Earth . IM12, for example, spans parts of Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. (Throughout the conference, speakers playfully identified themselves by bioregion code rather than nationality.) Even “Asia” itself was framed ecologically and culturally, defined by regions shaped by intensive rice cultivation.

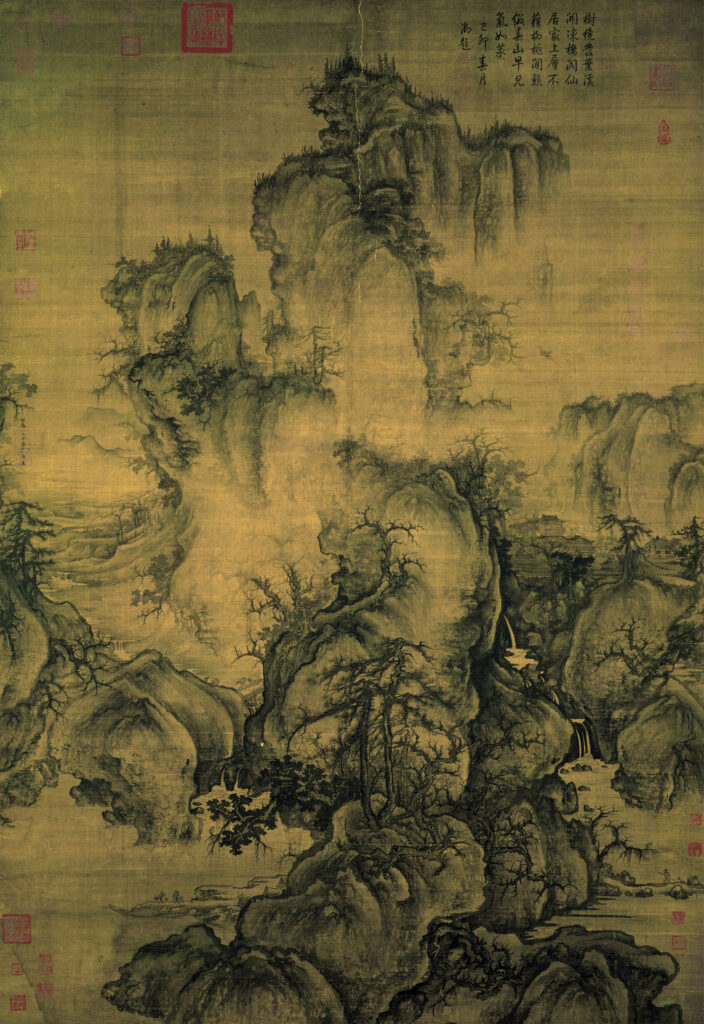

Against this backdrop, speakers offered historical and philosophical perspectives on “mountain and water.” Eugene Wang , Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Asian Art, introduced ink landscape paintings by the 11th-century master Guo Xi. Unlike Western traditions that often present nature as an object for detached contemplation, Guo Xi’s work envisions a world intertwined with embodied experience. Drawing on aesthetic theories that parallel the human body and the landscape, Wang described one painting as a skeletal framework of mountains animated by a circulatory system of streams and mist.

Other participants expanded the concept beyond human scale. Yukio Lippit , Jeffrey T. Chambers and Andrea Okamura Professor of History of Art and Architecture, examined Hokusai’s famous prints of Mount Fuji. Even within formal constraints, the 19th-century artist’s work suggests a radically expansive conception of nature. Drawing on contemporary philosophy, Lippit characterized certain scenes as representations of “hyperobjects”—forces such as wind that shape human experience yet are distributed so broadly across time and space that they resist representation in human terms.

Redefining humanity’s place within the natural world is central to the work of Yu Han Goh, principal of the Malaysia- and Singapore-based firm Salad Dressing . “We ask what it might mean … for value to be measured beyond human preference,” she said. Placing her practice in dialogue with artists Pierre Huyghe and Anicka Yi, Yu Han described designing landscapes “where agency is distributed across humans, nonhumans, and temporal forces.” For a botanical garden in Malaysia, she and her collaborators envision sensors and AI technologies that would allow visitors to perceive sound and light spectrums normally accessible only to other species—facilitating new forms of interspecies cohabitation. “To co-exist,” she said, “we must learn how other beings perceive the world.”

Although the conference conceptually blurred political borders, the influence of political economy remained visible. Youngmin Kim (MLA ’06), professor of landscape architecture at the University of Seoul, described the profession’s rise in South Korea as part of a nation-building effort under Park Chung Hee. Park recognized the need for landscape architecture to support reforestation, water management, beautification, and infrastructure development—establishing foundations that continue to shape the field.

The relationship between government and landscape architecture is equally urgent for Kotchakorn Voraakhom (MLA ’06), founder of Landprocess in Bangkok. Warning of her city’s vulnerability to intensifying rainfall, she urged practitioners not only to demonstrate sustainable practices but also to “convince people of a better future.” She cited the ambitious refurbishment of a Thai government complex—reducing car traffic, expanding pedestrian spaces, and installing rooftop gardens and solar panels—as an effort to align “green” rhetoric with tangible action. The creation of appealing, livable public spaces, she argued, gives designers leverage. “We are the profession that makes the government relevant.”

One of the most moving moments of the conference came when Gary Hilderbrand, chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture and Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice, offered a remembrance of Kongjian Yu (DDes ’95), who had been scheduled to speak before his tragic death in a plane crash last year. His influence resonated throughout the proceedings. Turenscape , the Beijing-based firm he founded, was represented in the exhibition by projects demonstrating his “sponge city” approach to urban wetland design.

A recording of Yu discussing shanshui in a 2024 GSD seminar, led by Jungyoon Kim, was played in his absence. He noted that the aesthetic concept emerged from elite traditions, while most people historically engaged the land through labor and shaped it to survive. That lived knowledge informs Turenscape’s terraced flood landscapes, which echo traditional rice paddies while mitigating urban flooding. Dong Wang of Turenscape spoke about continuing the firm’s mission, presenting compelling examples of wetlands replacing canalized concrete rivers to create space for water rather than attempting to confine it.

Some of the conference’s sharpest reflections came from outside the discipline. In his remarks on the opening night, Harkness, a professor of anthropology, offered what amounted to a manifesto for landscape architecture in an era of climate change. “Landscape architects design for motion, change, and dynamics,” working in dialogue with a shifting planet and the nonhuman forces that shape our lives, he observed. As those forces grow increasingly powerful—and at times catastrophic—practitioners who collaborate with the natural world rather than attempt to constrain it are more relevant than ever.

“Designers of Mountain and Water: Alternative Landscapes for a Changing Climate,” the conference and affiliated exhibition, are organized by the Graduate School of Design and the Korea Institute, Harvard University. They are also supported by the Harvard University Asia Center, the Southeast Asia Initiative, the Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies, the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, the Harvard-Yenching Institute, the Kim Koo Forum at the Korea Institute, and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. The project is also supported by Daniel Urban Kiley Exhibition Fund at the GSD.