Frank Gehry’s work has often been described in terms of force: a force that shaped buildings into the most improbable forms, that recentered civic centers within cities’ downtown cores and their waterfronts, and more broadly shifted the trajectory of contemporary architecture. Those narratives are not wrong, but they are incomplete. To remember Frank only as a monumental figure in the discipline is to overlook what, to many of us who were lucky enough to know him, was most powerful about him: a quiet, stubborn, and deeply personal compassion that permeated his artistry, practice, teaching, and philanthropy.

Frank’s formal and technical accomplishments are evident in the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, as well as many other cultural, academic, and civic buildings that have reframed how we think about monumentality, material, and the relationship between city and icon. But further, these projects are threaded by a persistent question that defined his practice: what might architecture do for people who live with it? After completing his studies in architecture, Frank began an urban planning degree at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1956. It was his hope that he would see the linkage between individual buildings and the way they come together to shape cities. While he was unable to complete the program, he internalized its core values. Throughout his career he designed architecture understanding and respecting cities, their citizens, and the sociospatial conditions that enliven them.

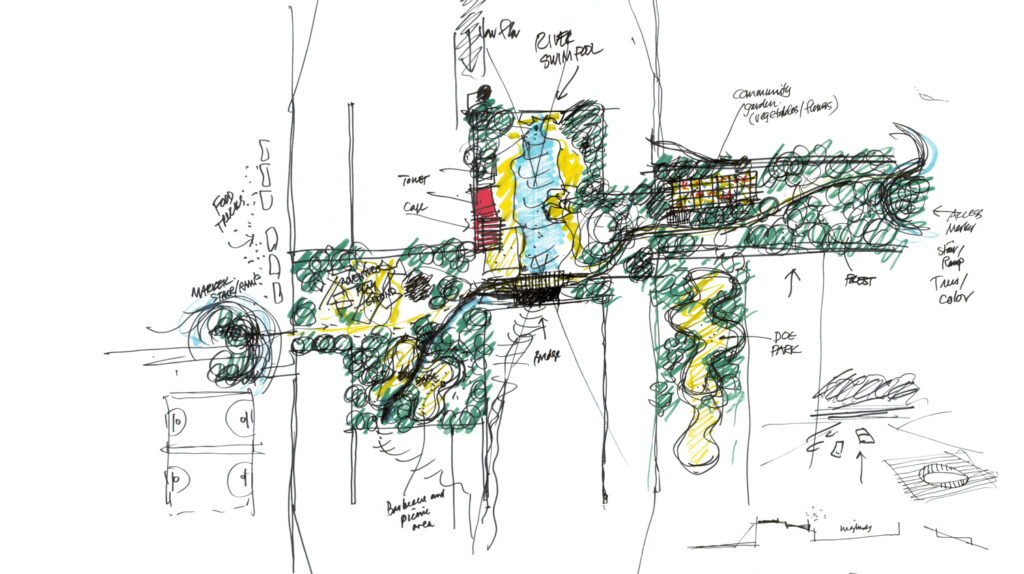

Frank’s compassionate design hand extended far beyond capital-A Architecture. The LA River Master Plan (2022) was one seminal project in which Frank sought to shape lived experience through the built environment. The planning effort, completed in partnership with OLIN and Geosyntec, studied the 51-mile stormwater management channel as an underutilized public asset. For Frank, the project was transformational. It reimagined the river and would bring Los Angeles County residents back to its banks through parks and open space development, cultural and educational facilities, new opportunities for affordable and supportive housing, and revitalized ecology. I worked alongside him throughout the plan’s four years and can attest to his sincere love for the community and a goal for equitable, quality public space.

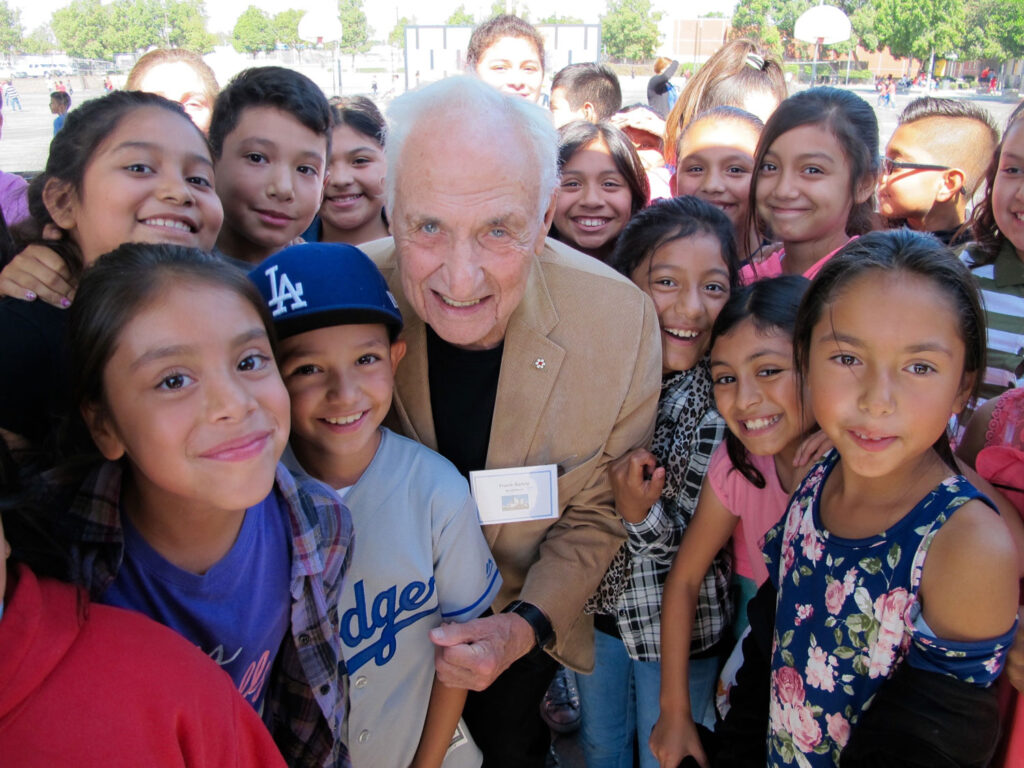

Frank’s commitment to social good—particularly in arts education—further reveals the fuller picture of who he was. As a supporter of Turnaround Arts California and Youth Orchestra Los Angeles, he understood that access to the arts for under-resourced youth was not an ancillary concern but a central civic responsibility. He championed arts education, especially for young people throughout LA County, in an era of public divestment from the arts. While orchestrating global cultural landmarks, Frank similarly cared deeply about a child’s opportunity to draw, to create, to imagine.

In his teaching, Frank pushed even further into questions that many architects skirted, including criminal legal reform . At SCI-Arc (2017) and the Yale School of Architecture (2018), he taught studios in collaboration with organizations such as Impact Justice and A New Way of Life to study the future of prisons and the lasting harms of these systems. With his students he encouraged rigorous, uncomfortable, and necessary confrontations with the ways space is weaponized against those most vulnerable among us. As part of the studio teaching team, I saw firsthand how the classroom became the site for radical empathy, asking students to consider the lives of incarcerated people, of families and communities destabilized by carceral systems, and of what it might mean to design toward repair rather than punishment.

I came to Gehry Partners in 2017, following years of architectural education in which I never felt quite talented enough nor that I could ever “fit the part.” The mythology of the starchitect loomed large, and I expected distance—if not arrogance—from a figure of Frank’s stature. Instead, I found someone who made space.

For me, Frank reinstated confidence in myself following years of doubt. He allowed me the grace, time, and support to define architecture for myself. He never insisted that I subscribe to a singular ideology of form or style; he encouraged me, instead, to search. It was a seminal opportunity to seek architecture through our shared lens of compassion, commitment to the public, and interdisciplinarity. Even though years stand between my time at the office, this grounding in care—both for people and for the places we shape—has driven my explorations. The values that Gehry’s work embodied inspired my efforts to create a design practice that is first rooted in one’s personal accountability to society, a deep humbleness of positionality, and a love for beauty, place, and life that breathes into each individual project.

Frank was a mentor who listened more than he spoke, who offered questions instead of answers, and treated people with a foundation of respect. It is easy, from the outside, to mistake eccentricity or celebrity for substance. Being inside his world, what I witnessed instead was a man who deeply challenged the idea that architecture’s highest calling was to produce beautiful objects detached from social consequence. He held the rare belief that architecture holds a social consciousness.

Frank Gehry was a dynamic presence, and his architecture continues to reverberate with his grace across the world. In mourning his loss, we inherit a charge. To design with the same vision he brought to every project. To question with the same intensity he brought to every studio. And above all, to practice with a generosity of spirit that asks nothing in return except that we, too, try to make the world, both physically and socially, a little more beautiful than we found it.