Democratic Energy: Abby Spinak on the relationship between climate change and capitalism

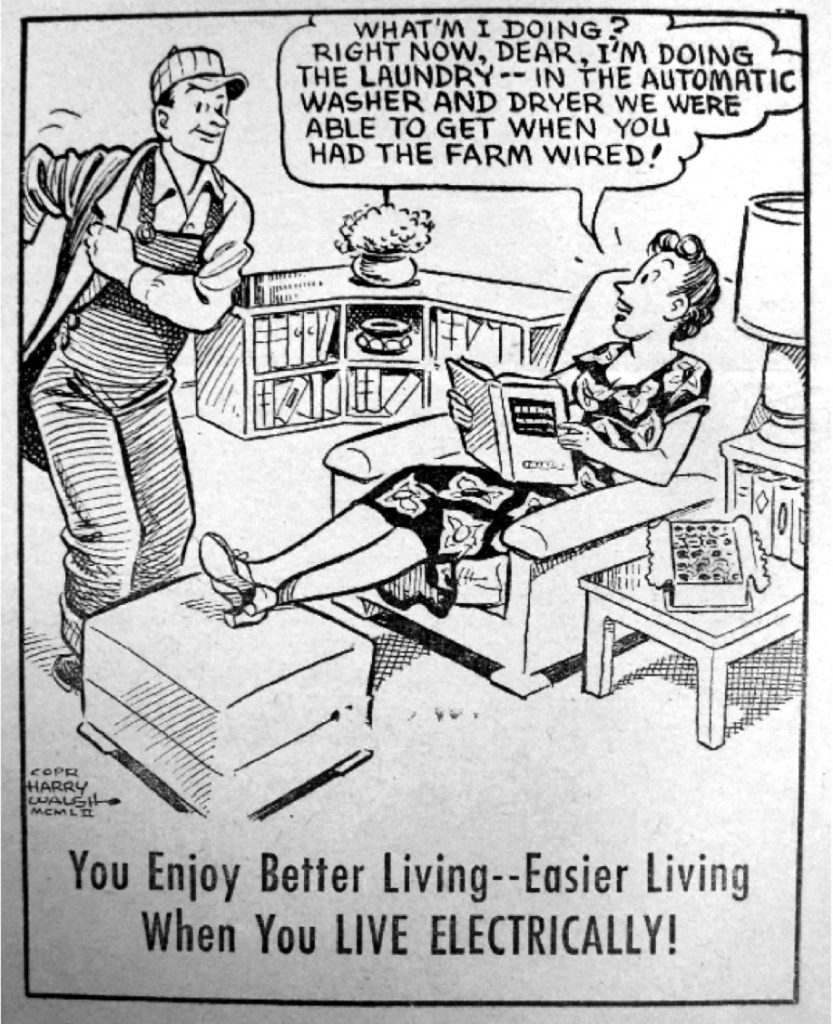

It is difficult to discuss the ongoing consequences of climate change without discussing its relationship to the history and current implementation of urban planning policy. Understanding our ecological and built environments is not simply a matter of technical knowledge and expertise; it also depends on recognizing the role that political and social infrastructures—in urban, suburban, and rural settings—have played leading up to the present-day crisis. Through her research, Dr. Abby Spinak—a lecturer in urban planning and design at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design—grapples with these issues as she focuses on the history of energy infrastructures and what it can tell us about the relationship between planning, design, and climate change mitigations.

After receiving her PhD in urban planning from MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Spinak held fellowships in the History of American Capitalism and the Energy Humanities. While working on her dissertation, she began to think deeply about what it means to protect local cultures, investigate alternative economies, and practice good environmental stewardship. She explains, “My time as a graduate student was influenced by climate change on one end and the economic recession on the other. As climate change was becoming a problem, coupled with market collapse, I found myself gravitating toward an area of study that was very critical of capitalism while asking about alternative economies and alternative approaches to work and labor.”

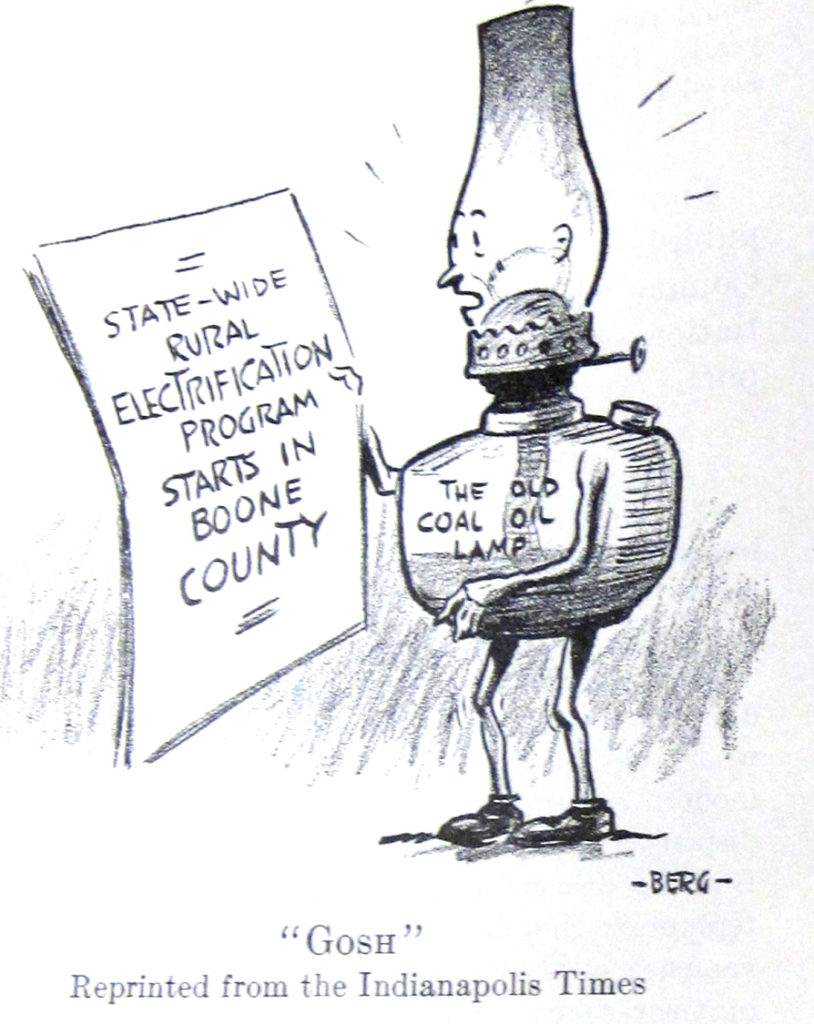

Spinak’s research resonated further with her own experience when she discovered that her family had belonged to an energy cooperative on Maryland’s Eastern Shore for years. They bought electricity from the co-op, but didn’t know that they could vote or have a say in energy policy. Networks of these cooperatives have existed in the United States for more than 80 years; and the model provided fertile ground for contemplating the radical social possibilities that could emerge from organizing energy resources in this way. What might democratic community ownership of electricity mean for our ability to address climate concerns? “I was curious about whether or not this was a latent landscape of democracy that was governing energy resources that had potential for being a bigger player in the new economy,” Spinak says. “I found very quickly that the answer was no,” she notes. Many of these co-ops, the result of New Deal funding, are quite conservative in nature. Spinak argues that tracing the loan constraints originally placed on these co-ops linked them more to the expansion of industrial agriculture and federal support for suburban and ex-urban development than to protection of the local farming communities that were intended to be the policy’s primary beneficiaries.

At its root, planning implies that we need something other than the market to govern society and action—a belief that is pretty counterculture in American society right now.

Abby Spinakon the opportunity for planners to challenge epistemologies surrounding climate change

So understanding the historical archive is central to Spinak’s work as a scholar and educator. “One of the reasons that I think teaching history to planners is so important is that it demystifies existing institutions, the existing built environment, and the existing model for infrastructure delivery. There is nothing sacred about the status quo,” Spinak says. Planning can be reparative and experimental, and a close reading of history reveals this, just as it reveals the gaps and chasms of precedents. What’s more, a study of history encourages confronting multivalent, and, at times, opposing, problem-solving strategies within a wider discourse on climate change.

Given the reality of multiple markers of crises along various historical timelines, it becomes important to examine our visions for the future in this moment of widespread global change and to understand the possible impacts of any revisions. In this context, Spinak’s research into energy infrastructure invites reflection upon the potential political transformations that can occur within hyperlocal contexts.

For Spinak, reparative planning is a marriage of theory and practice—an emphasis that she brings into the classroom: “What I’m more concerned about is, How does it translate? Are my students actually taking this and doing something with it?” She offers the example of one of her students, Jennifer Matchett, who is currently working with an indigenous community in the Yukon to design solar energy projects within the frameworks of indigenous knowledge. Rather than appropriating the “best practices” of a solar industry informed by settler colonialism, this community is envisioning how a new solar grid—one that functions within its own regional economy—becomes a technology that supports local indigenous governmental and social infrastructures.

“At its root,” Spinak says, “planning implies that we need something other than the market to govern society and action—a belief that is pretty counterculture in American society right now.” Planners have the opportunity to challenge epistemologies surrounding climate change; they can weigh in on matters of social and economic justice, not just on scientific or technical factors such as carbon emissions. They must confront the social outcomes of ecological instability: Think the slow disappearance of coastal communities. Her current course, Climate Justice, addresses these issues by looking at climate change as a symptom of broader structural inequality and enduring geopolitical violence.

Spinak believes in the radical role that planners can play: “One of the applications I see of my research at the GSD is its ability to teach people to be more critical of the historical dependencies that have constructed the world around them and to know that if they change things, they are not disrupting this perfect logic, but trying something new. That’s all design and planning has ever been.”

Empty Monuments: Kaz Yoneda’s research on Olympic stadiums considers the future of cities

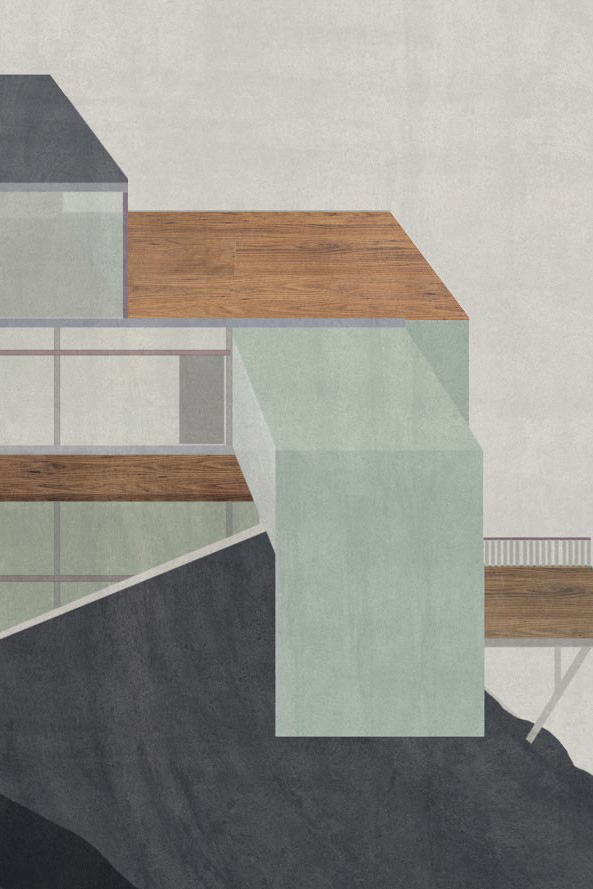

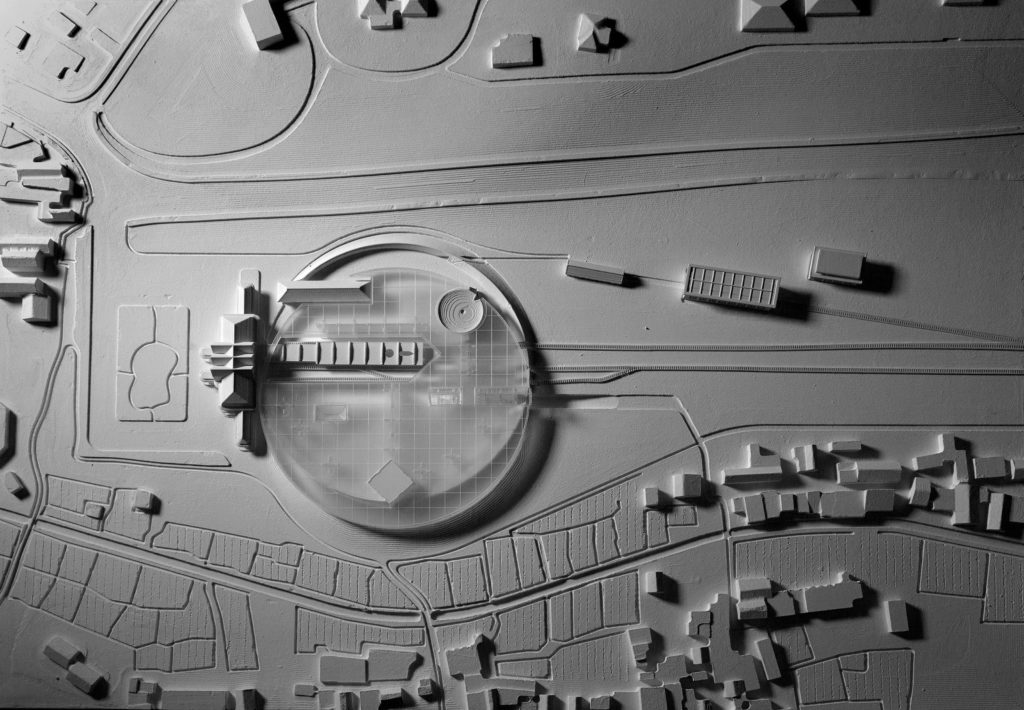

Just a year after the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, many of the stadiums built for the tournament had settled into disuse. Brasilia’s Estádio Nacional, for example, became a $550 million bus parking lot. This landscape of empty monuments, compounded by massive national debt, was not an aberration. Many blame the 2004 Athens Olympics for contributing heavily to Greece’s spiraling economic crisis, and other cities and nations that have hosted global, large-scale events have experienced similar challenges. But such outcomes are not foregone conclusions, according to Kaz Yoneda, design critic in architecture and the founding principal of Tokyo-based firm Bureau 0-1 and a 2018 Richard Rogers Fellow .

Yoneda used his three-month fellowship to analyze the London 2012 Olympics in order to improve preparations for Tokyo 2020, and to consider the futures of cities more broadly. His particular concern was legacy planning—the concept that buildings can solve present needs but should also be constructed with an awareness of, and hope for reappropriation by, future generations. “These types of events always expose the issues inherent to any host city,” he says. “A two-week event is not a city’s apotheosis. Cities don’t change in that time. What’s important is what happens 10, 20, and 30 years later. That architecture and urban spaces are able to adapt and take on changing cultural values is a beautiful thing.”

London serves as a prime counterexample to Brazil and Greece, as Yoneda learned when he visited the former venues and interviewed designers and architects involved in the games. “A huge legacy master plan existed years prior to the Olympics to develop the eastern track of the city that had been devastated by Nazi air raids and which subsequently became an industrial area with low-income housing,” Yoneda explains. “The goal wasn’t so much to build grandiose venues or develop luxury condos but to increase the average lifespan of East Londoners. And in order to do that, you need better hospitals, better living environments, better green spaces, and better education.”

A two-week event is not a city’s apotheosis. Cities don’t change in that time. What’s important is what happens 10, 20, and 30 years later. That architecture and urban spaces are able to adapt and take on changing cultural values is a beautiful thing.

Kaz Yoneda on planning Olympic facilities with long-term development goals in place

Tokyo does not have any such framework or vision in place—an absence that is a primary consideration of the international think tank xLab . Co-founded by Hitoshi Abe at UCLA and Kengo Kuma and Atsushi Deguchi at the University of Tokyo, the group focuses on imagining future environments with an emphasis on melding physical and digital spaces through interdisciplinary engagement.

During xLab’s recently concluded three-year summer program, Yoneda led courses concentrated on a set of core themes: community (2017), mobility (2018), and resilience (2019). This year, he and Miho Mazereeuw developed a syllabus around Harumi Flag, an athletes’ village under construction in the Bay of Tokyo. Of major concern is the site’s future stability. “Because it’s a landfill, it has a very weak foundation,” Yoneda explains. “It’s prone to soil liquefaction. The question is, When it’s eventually turned into a mixed-use high-end residential complex, how resilient will it be if an earthquake occurs and a tsunami hits the area?”

Yoneda believes that one way to mitigate the legacy of poor planning is to involve the local community. “We took a ground-up, incremental, small-scale approach to the idea of resilience because people are creative and strategic about how they can use their surroundings,” he says. “Citizens living in an area can become stakeholders who practice disaster prevention while living their everyday lives. It makes prevention second nature because you’ve trained subconsciously in your everyday learning.”

Future Olympic hosts may be better prepared. In 2018, the International Olympic Committee approved “Agenda 2020, the New Norm,” a manifesto featuring 118 reforms that could diminish the emphasis placed on iconic, individual buildings and shift attention to long-term development goals. “I wish that it had already been in place when Tokyo was chosen because that might have forced the organization and the city to push for a legacy plan,” Yoneda says.

He remains hopeful about the future, however, because he sees alternative solutions to governmental interventions. “Tokyo is very complex with a lot of players, and anything you do here requires collaboration and an interdisciplinary team,” he explains. “It will change at a grassroots and private-sector level, through coalitions of the willing—real-estate developers, architects, designers, producers, media outlets—who are interested in the long term.”

September 2019 News Roundup

“Drawing Attention: The Digital Culture of Contemporary Architectural Drawings, ” at the Roca London Gallery, explores contemporary architectural drawing and features an expansive collection of over seventy drawings from established and emerging practitioners around the globe including Jimenez Lai, CJ Lim, O’Donnell + Tuomey, and Neil Spiller. Co-curated by Grace La, the exhibition is part of the London Design Festival .

Anita Berrizbeitia gave a keynote lecture at the International Federation of Landscape Architects’ conference in Oslo. “Given the current challenges of species extinction and resource scarcity, I pose that the landscape will increasingly be the space where the conflicts between the interests of the few versus the need of the many are registered and negotiated,” wrote Berrizbeitia in an introduction to her lecture. The conference took direct aim at the climate crisis, asking how landscape architects can mitigate the destruction of nature and people.

Laier-Rayshon Smith (MUP ’20) was awarded an APA Foundation Scholarship . Smith’s vision for equitable communities includes working at the intersections of social interaction, policy, design and the decision-making processes that formulate the built environment. Experience working at non-profit organizations in Pittsburgh helped to shape this vision. The APA Foundation’s mission is to advance the art and science of planning through philanthropic activities that provide access to educational opportunities, enrich the public dialogue about planning, and advance social equity in the profession and in our communities.

Justin Stern (Ph.D ’19, MUP ’12) is the new Pollman Fellow in Real Estate and Urban Development 2019-2020. Stern’s research focuses on the interplay of economic development, technological disruption, and urban form in the rapidly urbanizing regions of East and Southeast Asia. As a Pollman Fellow, Stern will work on the research project “Offshoring, Automation, and the City: Mapping the Urban Futures of Global Outsourcing Hubs,” which builds on his dissertation. The research will address BPO automation in Bangalore, Johannesburg, Kraków, and Manila. Topics will include how local governments, real estate development corporations, and others prepare for the threat of BPO automation, and what lessons can be learned about functional building obsolescence caused by societal, economic, and technological changes.

Khoa Vu’s (MArch I ’19) thesis “Grayscale,” advised by Preston Scott Cohen, was recognized as one of the winners of 2019 Architecture MasterPrize in the Cultural Architecture category. “Grayscale” exploits the inbetween as central to providing a new design methodology and spatial type. The aim of this thesis is to discover spatial conditions that exist between nature and the man-made, the old and the new, the inner, imaginative mind and the external, perceived world. The project proposes a new Cultural and Laboratory Hub for a highland resort city in Vietnam called Dalat, “the city of fog and thousands of pine.” The thesis will be also exhibited at the GSD Dean’s Wall from 10/21 – 12/20, selected by the Chair of Architecture Department Mark Lee.

Weiss/Manfredi was recently selected as one of three finalists for Reimagining La Brea Tar Pits, an international competition for the historic museum and park in Los Angeles. DS+R and Dorte Mandrup (Copenhagen) are the other two finalists. In reimagining the 13 acres of Hancock Park, La Brea Tar Pits, and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the architects assembled teams that included not only architects and landscape architects, but scientists, engineers, designers, and artists. Recently, Weiss/Manfredi’s Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park won the Spaces, Places, and Cities category in the 2019 Fast Company Innovation by Design Awards . Both the Brooklyn Botanic Garden Overlook and Tulane University Commons are opening to the public this fall.

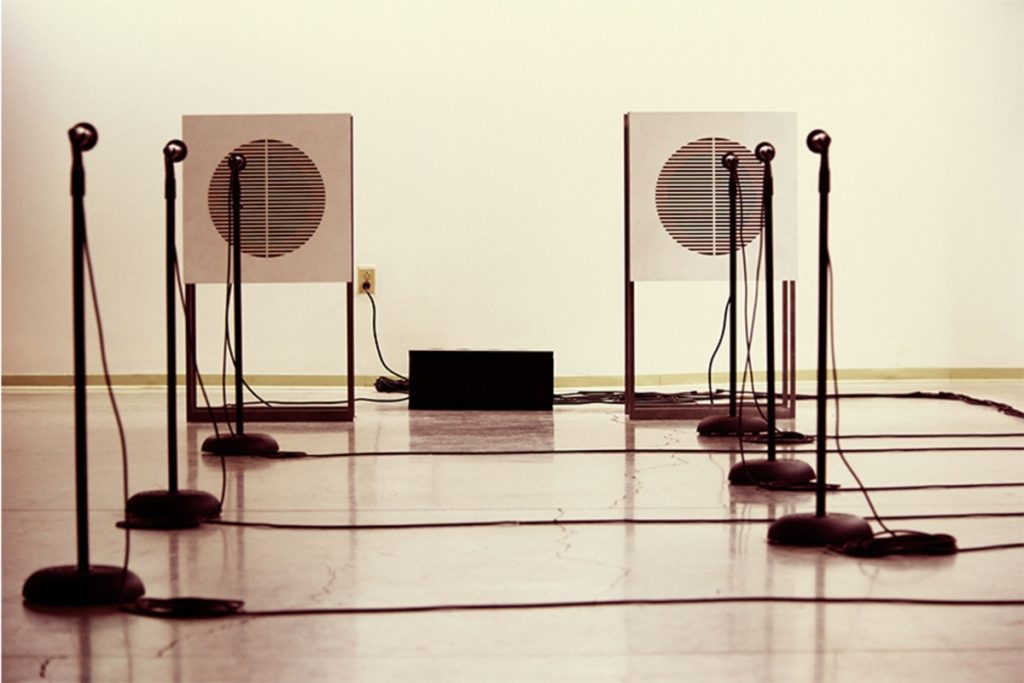

Robert Pietrusko’s sound installation Six Microphones, which was exhibited at Storefront for Art and Architecture in 2013 and at the Carpenter Center in 2015 is being released by LA-based record label, LINE: Sound Art Editions . It is now available for streaming, digital download, and on double vinyl.

Jesse Keenan published an article in Science entitled “A Climate Intelligence Arms Race in Financial Markets.” The articles focuses on black box technology and public science integrity issues in built environment systems associated with climate adaptation planning and investment. Science is one of the most prominent journals in the world among all disciplines. Currently, it is ranked #3 behind Nature and the New England Journal of Medicine.

Alex Krieger published an editorial in The Business Journals entitled “Viewpoint: The many lives of Boston’s Old Corner Bookstore”.

The House Is a Work of Art: Kazuyo Sejima on her fascination with “Shinohara’s way”

The diffuse spread of artistic thought and technique that we call “influence” impacts architecture in ways that are often difficult to discern. In his essential study, Influence in Art and Literature, Göran Hermerén explains that the notion of influence is broad and complicated: “Every work of art,” he writes, “is surrounded by what might be called its artistic field.” This includes not only the ideas of other artists, but traditions, contemporary philosophy and politics, the desires of sellers and buyers, the voices of critics, and so on. In architecture these expand to include legal restrictions, topography, context, and the practicalities of budgets.

All of these forces shape the work of designers, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly, so that every work must be understood as, in some way, a product of its artistic field. Usually, though, the question of influence gravitates toward progenitors—“Which designer impacted your work, and in what ways?” Even simplified like this, the question presents a challenge because when designers are at their most susceptible to influence—as students or early in their careers—they are often least able to clearly discern the origins and directions of forces that are affecting their work.

This point came out forcefully in “Reflecting on Shinohara,” a conversation earlier this month between the Pritzker Prize–winning architect Kazuyo Sejima and Harvard architectural historian Seng Kuan. When describing Kazuo Shinohara’s impact on her work, Sejima paused in her recollections, noting with some amusement that young people sometimes don’t clearly realize their influences. While it was evident later that Shinohara had affected her thinking as an architect (which he pointed out to her in a conversation around 1990), how he did so wasn’t apparent at first.

Sejima remembered feeling “really shocked” on seeing Shinohara’s houses published in magazines while she was a young home economics student. She was particularly taken with his aphorism “the house is art,” a notion that was so different from what she and her classmates at Japan Women’s University were learning in the late 1970s. Their impulse, Sejima said, was toward the practical. “Circulation should be short,” “the dining room should be next to the kitchen,” and it was important to accommodate the simple lifestyle still prevalent in Japan since after the war.

Shinohara’s houses, however esoteric they might have seemed, appealed to these students because they were somehow realistic. Having been built in the postwar era, they appeared to respond to the scarcity of materials by making it “important to use thin, small members,” she explained, while still avoiding an impression of poverty. So, even as Sejima and her peers admired the monumental space frames of Kenzo Tange’s Osaka Exposition Hall, or the sweeping roofs of his Olympic venues, they were, she said, “fascinated with Shinohara’s way.” His simple, “and very difficult to understand” line drawings, accompanied in magazines by Koji Taki’s bold black-and-white photographs, offered a “very strong expression to us,” she explained.

These were youthful, and perhaps unsophisticated first impressions of Shinohara, whose influence on Japanese architecture in the late 20th century was immense, and whose work expressed subtle, challenging ideas about architecture in Japanese culture. He famously described the progression of his career in four distinct stages, each associated with an intense theoretical preoccupation.

In the first stage, he sought to condense what he called “a hot meaning cultivated in the long process of history.” His domestic spaces in this first phase expressed the “underlying abstract structure” of traditional Japanese building elements and their composition. In the second phase he shifted attention to the cube, a less semantically rich architectural figure, in an effort to create, he explained, “an anti-space” or “a cold space” that could express “an inorganic, neutral, or dry meaning.” In his third period—which coincided with Sejima’s time as an undergraduate—he experimented with assemblages of raw, functional objects without “any predetermined or prescribed intents.” Using posts, walls, and braces he sought to produce a “zero-degree machine” that could express the “chaos which generates the liveliness… of the contemporary metropolis.” His fourth phase, the subject of the “Shinohara Kazuo: ModernNext” exhibition on display in the Druker Design Gallery in the Graduate School of Design’s Gund Hall, elaborates on the idea of urban chaos, the near infinite complexity of modern machines, and the meaninglessness of their individual parts. This phase, which Kuan described in his opening remarks as a “counterpoint to postmodernism,” addressed not only the contemporary conditions of Japan, but also its position in a globalizing world.

While Shinohara expressed this thinking in 42 buildings, mostly houses, over the course of a long career, he also communicated his ideas to students at Tokyo Institute of Technology, where he served as professor of architecture from 1970 to 1985. In this context his influence was very direct. He gathered a group of students and collaborators—particularly Kazunari Sakamoto, Itsuko Hasegawa, and Toyo Ito—into what came to be known as the Shinohara School. The influence of these prominent architects rippled outward, as Kuan explained in conversation with Sejima, to “a very prominent group of young architects in the next generation.”

Although we can trace an architectural lineage (with offshoots and clusters) among these architects, it is perhaps more useful to envision a changing artistic field that surrounds the production of architecture in Japan. Shinohara was a prominent force within this field. So his investigations into the attenuation of tradition, the nonexistence of space, the rawness of architectural elements, the chaos of the metropolis, and the expressive power of the machine did not end in his buildings or even at the close of each phase in his career. Instead they continue to find new channels of expression in the hands of his students and devotees—and among architects who might have first encountered his work while flipping through pages of an architecture magazine, attending a lecture, or examining models and drawings in an exhibition of his work. “ModernNext” and the events surrounding it will no doubt contribute to amplifying the artistic field that surrounds Shinohara’s work.

“Reflecting on Shinohara” was organized in conjunction with the exhibition “Shinohara Kazuo: ModernNext,” on view through October 11, 2019 at Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Druker Design Gallery.

If it’s for us, but not with us, it’s against us: Hicham Khalidi on the challenges of curating in public spaces

Sprawling across entire cities, the biennial has become a prominent means for architects, designers, and artists to engage with pressing contemporary issues. But exhibitions on this scale pose particular curatorial problems. How can a curator translate idiosyncratic projects and the unique perspectives of the design disciplines into works that will resonate with the public?

For curator Hicham Khalidi, who delivered a lecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design this fall, part of the answer lies in understanding the public realm as a multilayered system. Just as urban spaces nest and overlap, the occupations of urban life—from homemaker to craftsperson to civil servant—form complex hierarchies. Khalidi believes that the task of a biennial’s curator is to translate projects vertically within this system. A single project can engage different people in very different ways, and large distributed exhibitions can bring projects to the people with whom they will resonate most strongly.

As the director of the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, Khalidi fosters the work of designers, architects, and fine artists of all stripes. But he is equally committed to the issues that impact the world at large. He is curating a biennial in Chandigarh that will be about water; another in Marrakech featured site-specific works that were about the city itself. For Khalidi, it is not a contradiction to operate in the public realm while simultaneously being committed to the personal visions of artists and designers.

What are the challenges of curating large exhibitions in public spaces and spread across cities?

Design and public space do not always match. (Architecture is the exception in which they do match.) The thing I want to tap into is public space, and to do this, novelty is important—the idea of being a novice and approaching things with a certain naiveté. I have always used this to my benefit. I am constantly in new spaces and new cities. So what is my process? Choosing artists, for example, is always a work in progress in these large biennials. I start with a hunch or an intuition, and I talk with artists about it. Then at some point I let go and let the artists create their own spaces. They create spaces that can nourish communication and create knowledge and activities to bring people together. In other words, artists have their own processes, and what I do as a curator is to lay down the groundwork for them.

Approaching complex issues with openness is a way of putting yourself in the place of the audience.

And not only the audience. Public space is not only a sort of free space for citizens to inhabit; it also has to do with rules, laws, city development, and ideas and hunches and aspirations. When I’m curating a large exhibition, I talk to a plethora of people that are involved with a shared public space, from residents to the mayor to government ministers. It is a vertical system. Depending on the country this is more or less difficult. In Morocco or India, for example, it is much harder than in the Netherlands, because there are more layers, and there is less communication across them. In Morocco, you have the city run by the mayor, then neighborhoods that are controlled by certain people, then also streets that are controlled by other people. So it is a matter of going through all these people and explaining the project to them. This can require yet another set of people to help with these translations—they are sometimes called fixers—who can bridge these gaps. In order to get the exhibition I want, I have to understand how these systems work and engage constantly in translations up and down the chain.

Public space is not only a sort of free space for citizens to inhabit; it also has to do with rules, laws, city development, and ideas and hunches and aspirations.

Hicham Khalidi on understanding the complex systems that dictate how a public space is used and perceived

What is the relationship of your work to disciplinarity: How do you integrate artistic disciples, craft, and other specialized knowledge?

At the Jan van Eyck Academie, we are very multidisciplinary, but when we begin to work, we don’t care about disciplines, we care about subjects. We understand that there are different viewpoints, different ways of understanding the world. A fashion designer uses fashion to understand the world—that’s it. I have worked in a wide range of disciplines, from cooking to theater, and I incorporate those interests into exhibitions. In my approach to public spaces and cities, I am not thinking about disciplines at all. In India, I am thinking about water. They have a water problem. To approach this I need as many disciplines as possible. I need science, engineering. So for a biennial, I also invite artists that have a practice that I think would work well in this situation.

What draws you to the process of curating?

Curating, for me, is just a way of understanding the world—and every time I approach a project, I approach it anew. I see curatorship as a very singular inquiry into what interests me as a person. Of course, a curator needs to make it public, but making something public does not mean scraping away this personal interest. A lot of what we do is to find each other through personal interests. I do follow trajectories, just as an architect will revisit themes in a series of projects, but I also approach artistic work as a very singular, personal process—even when I curate very publicly, with many people.

Climate change, justice, and resilience at Harvard Graduate School of Design

At Harvard Graduate School of Design, climate crisis and resilience is a subject that permeates all aspects of the curriculum, from coursework and faculty research to student projects, exhibitions, and public programs. In recognition of Climate Week, which takes place September 23–29, we’ve assembled a few of the many ways the GSD has engaged with climate change this year.

Faculty Research

Which regions and cities in the United States will provide refuge for American climate migrants? As principal investigator for “Duluth Climigration,” lecturer in architecture Jesse M. Keenan collaborated with a team of GSD students to research the viability of the City of Duluth as a suitable destination for climate migrants. Recently featured in The New York Times , the project engages climate adaptation planning, demography, market analysis, design research, and infrastructure analysis to explore a range of scenarios for the physical adaptation of Duluth. For more about Keenan’s research, read about “climate gentrification” in Miami and Detroit or the brewing conflict of interest between financial institutions and the ever-expanding climate services technology industry in the journal Science .

In episode six of our podcast Talking Practice, host Grace La interviews Gary Hilderbrand, founding principal and partner at Reed Hilderbrand, and Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture. The pair discuss the trajectory of landscape urbanism, highlighting the ways in which new modes of representation have impacted the scope and capacity of landscape architecture to imagine larger systems, and to engage with climate change.

Curriculum

A threatened coastline presents particular challenges to the communities–and ecosystems–of coastal regions. Studios The Monochrome No-image, led by Rosetta Elkin, and Adrift and Indeterminate: Designing for Perpetual Migration on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, led by Gary Hilderbrand, examine regional interventions that might mitigate the effects of a rapidly deteriorating shoreline on the Barrier Islands of the eastern seaboard and Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

This fall, Urban Planning and Design’s Abby Spinak is leading a course on the topic of Climate Justice. Students will “ultimately ask what new kinds of practices, knowledges, and collaborations are necessary to build more just and responsible relationships between people and the nonhuman world, and with each other.”

Public Programs

On October 28, landscape architect Teresa Galí-Izard will give a lunchtime lecture about decentralizing the role of humans within the landscape. How can acknowledging the agency of plants and other non-human actors influence climate outcomes across the globe? Learn more at 12 pm in room 112 of Gund Hall.

On November 21, Michelle Delk of architecture firm Snøhetta will speak to the GSD about creating places that enhance the positive relationships between people and their environment. What are the direct outcomes of a stronger mediation between the built and natural world? Hear more at 6:30 pm in Piper Auditorium.

Alumni Activities

How does an individual’s creative capacity impact a changing climate? On September 28, Susan Israel (AB ’81, MArch ’86), President and Founder of Climate Creatives, will lead a workshop at the Arnold Arboretum around the topic of a creative climate commitment. Free for Harvard University students. Learn more in the Harvard Gazette story “Using art to inspire action .”

Installed on Harvard’s Science Center Plaza last fall, the public-art sculpture “Warming Warning” aimed to inspire dialogue about climate change and viewer engagement with a shape-shifting, participatory exhibition. The piece was conceived by Harvard Forest Fellow David Buckley Borden (MLA ’11) with Harvard Forest Senior Ecologist Aaron Ellison.

Student Projects

Prize-winning thesis “Lines in The Sand: Rethinking Private Property On Barrier Islands” by Maggie Tsang (MDes ’19) and Isaac Stein (MLA/MDes ’20) examined the role of private property in transforming the landscape of the barrier islands, using North Carolina’s Outer Banks region as their case study. Their research proposes an “alternative land trust” as a way of returning coastal territories to their natural function.

In the following work-in-progress video, Melissa Green (MLA ’19) describes her final project for the spring 2019 option studio “The Monochrome No-image” led by Rosetta S. Elkin.

Looking for more? Browse our climate change topic.

On view through October 20, A Hole in the Wall exhibition presents an intimate reading of space

We usually don’t think much about what a thing is, because its self-evident qualities make it understandable: A chair, a desk, a brick all seem complete and coherent enough. But as soon as we look into things deeply and philosophically, as the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty has done, they become far less coherent. Objects “behave as though they had an internal principle of unity,” he says, but “they are only mild forces that develop their implications on condition that favorable circumstances be assembled.”

A chair presents itself as a chair from the right distance and angle, but get too close and it becomes other things—legs and joints, or wood. A wall is more ambiguous than a chair; it is sometimes discrete and freestanding, sometimes continuous with other walls, floors, and ceilings. It is always made of many parts: bricks and mortar, or studs, insulation, and sheathing. The space between walls is more ambiguous still, being only vaguely definable and with variable—sometimes inexplicable—qualities and intensities.

Art often finds value in the gaps. When the writer Italo Calvino advocated for precise language and description in literature, he gravitated toward “the beauty of the vague and indefinite,” and “all those objects… that by means of various materials and minimal circumstances come to our sight, hearing, etc., in a way that is uncertain, indistinct, imperfect, incomplete, or out of the ordinary.” To write poetically about such things requires, Calvino claims, “highly exact and meticulous attention to the composition of each image, to the minute definition of details. … The poet of vagueness can only be the poet of exactitude.”

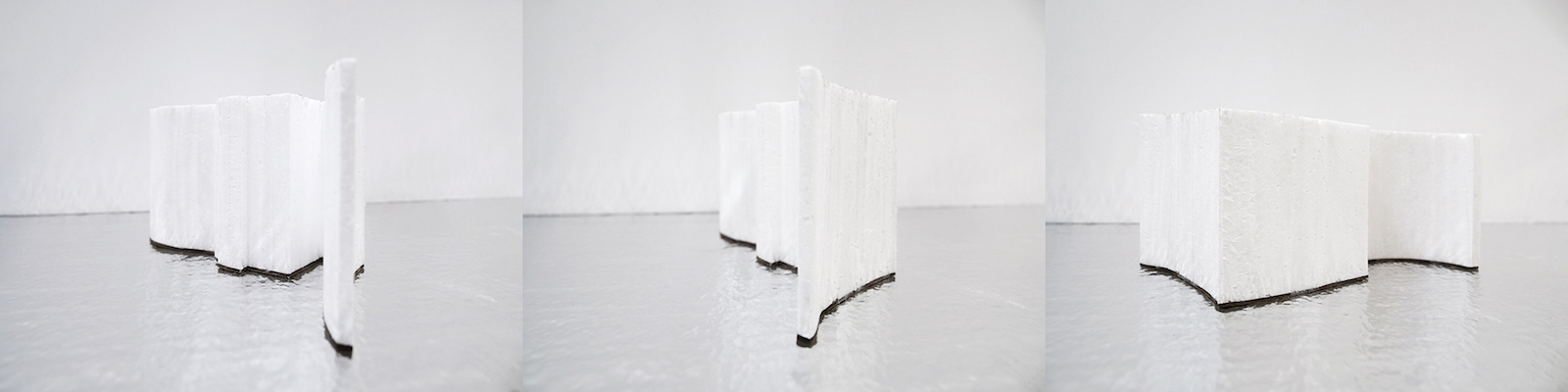

This fall, visitors to Harvard’s Frances Loeb Library will have the opportunity to experience a concrete manifestation of architectural vagueness in an exhibition designed by Graduate School of Design assistant professor Michelle Chang. A Hole in the Wall presents holes, gaps, cavities, space—all decidedly vague concepts—within the context of five freestanding walls, which are themselves conceived as “broad, vague masses.”

In the library, this space of imagination will start with holes—not apertures like windows and doors—but holes considered, Chang notes, as “a conceptual principle.” The origin of Chang’s thinking lies in an art restoration technique called in-painting. Conservators use it to repair damaged artworks by replacing gaps with something simultaneously vague and exacting. The replacement might include an approximation of the missing original highlighted with clearly identifiable paint strokes, or a precisely brushed color field that matches the surrounding context. It never involves filling the gap with an indistinguishable facsimile of the original.

Chang points out that this makes in-painting fundamentally different from content-aware fill, another process that influences her thinking about holes. Content-aware fill is used to repair raster images by drawing colors and patterns from surrounding areas to conceal voids with new information. Unlike this digital process, the goal of in-painting, historian of science D. Graham Burnett explains, is to “reconstitute the aesthetic unity of the work… while scrupulously honoring the work’s material reality.” In other words, filling the holes with in-painting preserves the ineffable qualities that make the work art while also accounting for the object’s history.

A curious aspect of in-painting is that it makes gaps and holes elements of primary concern. Similarly, in A Hole in the Wall, voids become central to the exhibition. Careful detailing of the walls accentuates places where openings shape the composition: score lines that facilitate warping of flat drywall panels, raw cut edges where each wall stands free of the ceiling, a reveal between the wall and the floor. At a larger scale, the habitable spaces between and inside the walls are filled with new possibilities—intimate reading spaces or unscripted spaces of imagination. A Hole in the Wall presents a newly configured library in which walls become vague and visitors linger in the gaps.

The Grand Tour: GSD’s Wheelwright Prize reminds architects of the power of global research

“Two years ago, when I received the call about the Wheelwright Prize, Mohsen Mostafavi mentioned that it was going to be life-changing,” Anna Puigjaner told an audience at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in October 2018. “And he could not have been more right. These last two years have been probably the most intense time of my life.”

In April 2016, Puigjaner was named winner of that year’s Wheelwright Prize , an annual GSD fellowship offering one exceptional, early-career architect a $100,000 award to fuel two years of travel-based research (or research-focused travel). Puigjaner had risen to the top of the field of over 250 applicants with her research proposal, Kitchenless City: Architectural Systems for Social Welfare. After winning the prize, Puigjaner undertook an itinerary beginning in Senegal before she worked her way through Vietnam and Thailand, followed by China and Japan, then Scandinavia, and finally a leg in Latin America.

In Peru, Puigjaner visited Comedores Populares, a service that feeds half a million people per day; in China, she toured You+, which houses more than 10,000 people in micro-sized, kitchenless units. These experiences—along with many other valuable site visits—allowed Puigjaner to better understand kitchen and communal-cooking typologies and, ultimately, forward her hypothesis that people might not really need kitchens in their homes after all.

In undertaking her Wheelwright Prize fellowship, Puigjaner joined a distinguished coterie of architects—among them Paul Rudolph, Eliot Noyes, and I. M. Pei—who had been selected as fellows over the years. It was a belief in the value of intensive, hands-on travel and the discovery of new forms of design that inspired the Wheelwright Prize’s founding in 1935 as the Arthur C. Wheelwright Traveling Fellowship. The core idea was to provide a beaux arts, “grand tour”-type experience to exceptional GSD graduates at a time when international travel was rare, and to stimulate cross-cultural engagement in both practice and pedagogy.

In 2013, then-GSD dean Mohsen Mostafavi reshaped the Wheelwright Prize as a competition open to early-career architects from around the world, whether GSD graduates or not. “It is clear that today’s fluid movement of people and ideas necessitates new approaches towards the understanding of architecture and urbanization,” Mostafavi remarked in 2013. “I am excited that in the coming years the Wheelwright Prize fellowship will be able to have a significant impact on the intellectual projects of young architects and, in turn, on the future of architecture and the built environment.”

Mostafavi revamped the prize in collaboration with the GSD’s K. Michael Hays and Jorge Silvetti (Hays remains on the prize’s founding committee; Silvetti served on the 2013 jury), as well as then-GSD communications director Benjamin Prosky and consultant Cathy Lang Ho. The committee discussed what a grand tour for architects of the 21st century would entail, and how themes and issues could be tied to geography and cultures. Their goal was to enable deep research that could enhance an architect’s personal formation as well as architectural knowledge at large. They concluded that this kind of experience would be most beneficial for early-career architects with open-ended curiosity and great future potential.

Since this reinvention, the Wheelwright Prize fellowship has spread in reach and engagement, enabling its subsequent six winners the opportunity to expand their architectural agendas and enrich their perspectives. Even with the comparative ease of today’s digitally enabled research and image-gathering, the opportunity to personally visit a diverse range of sites around the world, and to do so in a focused, prolonged format, remains invaluable.

“The architectural project works in many ways as a series of hypotheses about life and reality, but this reality that we project can be verified only through experience,” observes Chilean architect Samuel Bravo, winner of the 2017 Wheelwright Prize. (Bravo returned to the GSD on September 12 to present his Wheelwright travel and findings.) “So I think it is important to explore architecture as ethnography in a sense of exploring the experience of people. The experience of the built environment can only be revealed by ‘being there.’”

Bravo’s research proposal, Projectless, examines the relationship of the architectural practice with non-project-driven traditional and informal environments. He focused on a dozen cases in seven different countries to unearth, as he puts it, “a portion of the human environment that has been shaped in the absence of project.” Informality, otherwise understood as a people’s shared ability to create a city or collective living arrangement, is harnessed by “community architects” as a tool for creating and improving the built environment, Bravo notes.

The Wheelwright Prize’s investment in those ideas and practices percolating at architecture’s margins may bring immense benefit for the field at large. “Only a prize that prioritizes travel and open-ended discovery could allow an architect to do what Samuel Bravo wants and needs to do—to experience situations likely to range from primitive to chaotic, to live with and learn from diverse communities, to document common building knowledge, with the goal of transforming this knowledge into practicing concepts,” says Gia Wolff, who served on the jury of the 2017 Wheelwright Prize cycle. She also won the prize herself in 2013, its inaugural cycle after Mostafavi’s reinvention.

Over his two years of research, Bravo was able to observe working methods and toolsets across continents, from the hills of Lima to the city of Jhennaidah in Bangladesh. His travels allowed him to engage with the indigenous Matsés tribe, living in the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon. He learned about their construction of communal houses that, as Bravo observes, uniquely blend dwelling and being, revealing new clarity on the emergence of human environments in relation to language. He observed a series of other informal settlement areas, from the flooded slum of Belén Bajo in Iquitos (the capital city of Peru’s Maynas Province) to Korail in Dhaka, Bangladesh; he notes that Korail’s larger, more formal urban setup provokes questions about the nature and fundamental definition of informality.

“Through this process I met practitioners that, rather silently, have created a long-term engagement with communities,” Bravo says. “From city planners to community architects, these people are, in a way, expanding boundaries for our methods and strategies as architects.” He continues, “I feel the urgency of research on our rapidly changing realities. Architectural representation is a powerful tool to evidence the ignored. And architecture as a way of thinking about the human environment is also urgently needed.” As design fields are increasingly called upon in response to broad, complex, global problems, the sort of culturally engaged, boundary-questioning research that the Wheelwright fosters holds potential for architecture’s present and future agency.

The Humanitarian Activist’s Handbook: Understanding the role of architects and planners in humanitarian crises

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, at the end of 2018, there were 70.8 million people living around the world who had been forcibly displaced. As this number reaches a record high each year, humanitarian organizations work to meet new demands and concerns. And yet, according to Marianne Potvin (PhD ’19, MDes ’13), they have become mired in an unwavering focus on camps and shelters and have turned away from a tradition of innovation.

Potvin’s research at the Graduate School of Design focused on what she calls “humanitarian urbanism.” The concept’s definition is multifaceted. It refers to the international actors and organizations that work with refugees and disaster victims—with a specific emphasis on their relationship with spatial disciplines. And it also includes a broad consideration of “urbanism” that encompasses both the practice of urban planning and theories regarding human settlements.

With firsthand experience leading field teams for the International Committee of the Red Cross and other humanitarian NGOs, Potvin knew that she would need to base her research primarily on field manuals and handbooks, instead of on traditional architectural materials. “For many reasons, there just aren’t enough common instruments of architecture [from the field], such as plans or drawings,” she says. “During humanitarian crises, you might not keep archives, the instruments you have could get destroyed, or they may never make it back to headquarters where the centralized archive would be.” But she discovered that the unconventional sources are often invaluable and can contain “a lot more data than a single drawing.”

In the following conversation, she discusses the problem with camps, the changing role of technology in humanitarianism, and the vital—but undervalued—role of architects and planners in humanitarian organizations.

Designing a camp is attractive to an architect because it’s abstract, gridded, and has sensual characteristics that architects like. It is in part because of this that we have paid too much attention to, and been limited by, this frame of reference.

Marianne Potvin on the fascination among architects with designing the “perfect camp”

How does the academic vision of camps and shelters bump up against the reality on the ground?

When I was working as a shelter-and-settlement program manager in suburban Kabul, whatever I could get my hands on regarding camps was completely inadequate to my work. And yet, in the literature and especially in design schools, a lot of interest is in designing the “perfect camp.” Architects are obsessed with camps because they are considered the origin of everything—the origin of the city, for example. And yet they are always used as an example of the “non-city” in conversations about what is and is not a city. I think that categorization doesn’t get us very far because it doesn’t describe the conditions of humanitarian spaces, most of which are in between camps and cities.

There’s a camp fetish. Designing a camp is attractive to an architect because it’s abstract, gridded, and has sensual characteristics that architects like. It is in part because of this that we have paid too much attention to, and been limited by, this frame of reference. I’m not saying that work on the urbanization of camps isn’t useful, but it’s limiting.

In the older field manuals from the 1970s and early ’80s, there was often a sense that you needed to be conscious of the surroundings and respectful of local customs, that you should use local materials and be aware of the ways in which refugees live in these spaces. This was not very integrated into practice though.

The split between a camp and the local population echoes the ways in which walls both keep people out and imprison those within them. In a practical sense, not separating these two populations—geographically or metaphorically—could generate solutions that benefit everyone in a region.

A prime instance of this occurred in 2015 at the height of the influx of Syrian refugees into Lebanon. There was a no-encampment policy, so the refugees (who became one-fourth of the population) were dispersed everywhere. A water engineer working at a humanitarian organization told me that they were working on large projects, such as big water-distribution stations. Even though, conventionally speaking, humanitarian money isn’t supposed to go into hard, large-scale infrastructure, they were putting all their resources into this because they would provide water for the refugees as well as improve the conditions of the larger population.

Technicians are considered value-free problem solvers, and they are often not seen as strategic in shaping a humanitarian organization. My archival and fieldwork research showed that the international humanitarian law specialist or the refugee lawyer has a hierarchical position above the architect or planner. In fact, often there aren’t even distinctions made between the architect and the planner, or even the agronomist and the water engineer.

I argue that architects and planners are the ones who need to take the legal framework and figure out how to implement it—how a camp is planned, where you put it, how you decide whether to have a camp or if you go for, say, rent subsidies. That has a huge impact. There should be more cross-dialogue between the technical and legal units than there currently is.

There was even a moment in history when the United Nations Refugee Agency decided to call what they were doing “planning.” This was so important because it was a moment when they acknowledged that they were not just doing “refugee protection,” they were influencing urbanization issues. They have since completely forgotten about this.

Do you see technology, such as crisis mapping (which enables the collection of real-time data during disasters), playing a helpful role in humanitarian urbanism?

For a very long time, the dominant approach was for “appropriate technology,” which kept everything low-tech because of the idea that you couldn’t bring complex technologies into the “Third World.” Then in the last five to ten years, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, with a belief that AI will save us all and the assumption that new technologies will make the lives of humanitarians easier. I’m not advocating for a return to appropriate technology, but we should remember what we once thought about technology so that we can balance our current excitement. We just need to be cautious.

That being said, even though I criticize crisis mapping, it is useful. Crisis networks comprised of volunteers are forming to help people map their areas. A tool like this is democratizing the humanitarian field because all of a sudden you have a software engineer in Silicon Valley who may not go to Kabul for nine months but, with his technical expertise, can perfect a system of geographical features recognition.

These communities are going to challenge the humanitarian field in good ways. They’re raising the question about who the new humanitarians are.

The Death of the Genius: An alternative history of computation lays bare the problem of invisible labor in architecture

The development of the computer occasioned a radical paradigm shift in numerous fields. According to Matthew Allen (PhD ’19, MArch ’10), however, that was not the case for architecture. In his PhD dissertation, “Prehistory of the Digital: Architecture becomes Programming, 1935–1990,” Allen argues against the dominant narrative that the relationship between computers and architects began in earnest in the 1990s. He asserts instead that computational programming’s essence can be traced to the Bauhaus, and to modernism more broadly. And he claims that its effects—both structural and phenomenological—entered the field at a slow creep. It was subtle enough that some architects today believe they work the same way their predecessors did before the advent of technology, just with different tools.

Allen is a curious pluralist whose excavation of past traditions and, by extension, architectural processes, opens up the possibility of rethinking architecture at its most fundamental level. “We should not be defensive about what an architect is,” he says. “However you want to define ‘architecture,’ whether that’s the creation of environmental effects or the production of the spaces in which we all live, we should look broadly without predetermining it in an unhelpful way.”

In the following conversation about the occluded subculture of computational programming, Allen brings together Paul Klee, Le Corbusier, and the early structuralist dream of the computer in unexpected ways. He also provides a new lens through which to analyze the longstanding problem of invisible labor in the field of architecture.

Invisible labor and not valorizing collective labor enough are big problems in architecture right now. The pervasive, compelling myth still exists that someone called an architect designs a building; he might hire some people to draw it out for him or write up the details, but the idea belongs to this “genius” figure.

Matthew Allenon the dearth of “other figures” in architecture who students can look to as role models.

How does your research problematize the definition of “architecture”?

It’s hard to strike a balance between not taking the accepted definition for granted and giving your new definition immediately. Certainly, the architecture talked about by the computer-using architects was not what would normally be thought of as “architecture.” Design still occurred, but the methods were totally different from standard methods inherited from the Renaissance. The crux of the issue was these architects’ refusal to say that architecture is about how a building looks and that it is instead an activity and also the hidden structure with which designers work—whether that’s a linguistic structure that conveys meaning or a spatial structure that organizes how people use a building.

In what ways does this rethinking of architecture connect to the concept of programming?

“Program” is a 19th-century term for architecture, meaning the activities that happen inside a building. For example, a library has a certain program of having books, reading spaces, etc. While that use of the word is still around, in the mid-20th century the discipline of computer programming developed. But just a little before that, architects became interested in a way of creating architecture connected to this idea of the building’s program that was different from designing by way of drawing a facade and giving form to a building. With this new method, a programmer—who was more of a technician-type figure working in the firm’s back office—would be in charge of organization rather than a “genius” architect. This grew out of a modernist polemic of moving architecture away from fancy-looking buildings into a more technocratic profession of creating functional, cheaper spaces for all of humanity.

When does this movement converge with the advent of computer programming?

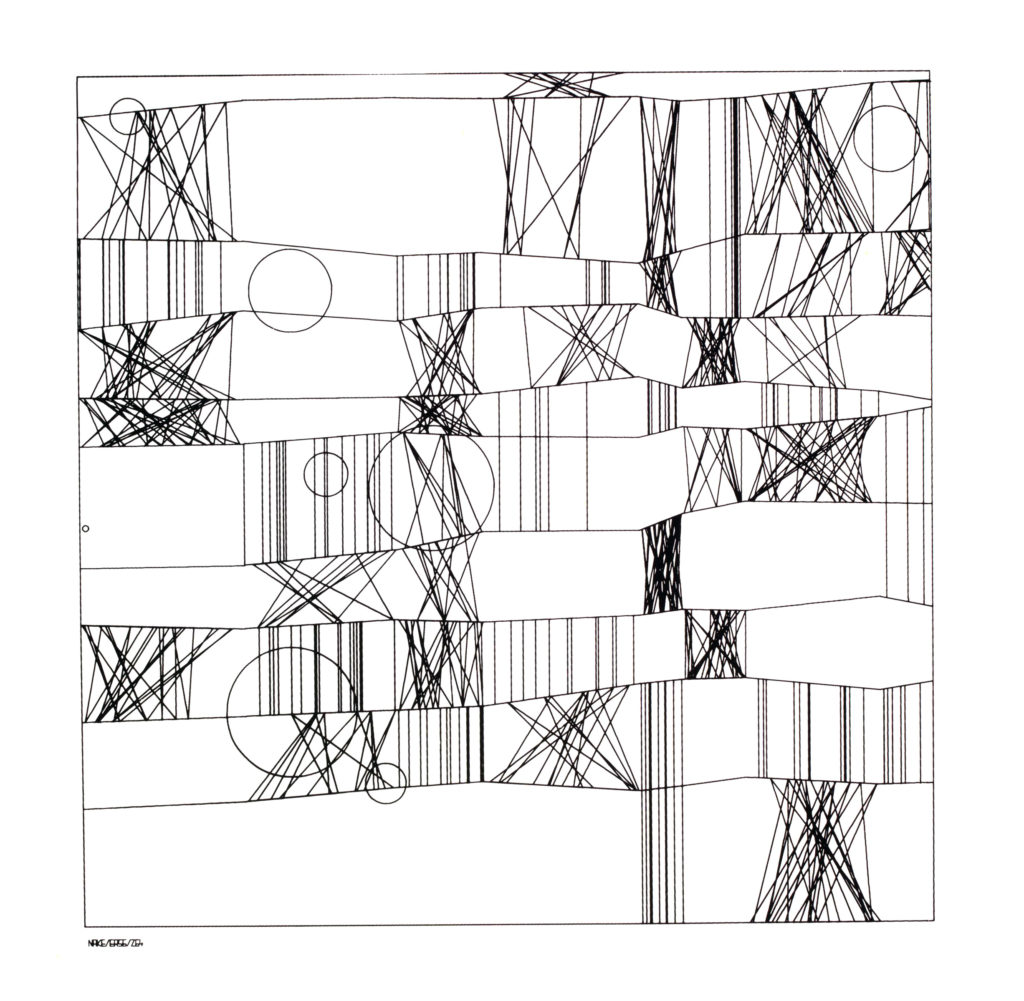

The change in modernism that you can easily see in abstract art also illustrates the changes occurring in architecture. A good figure to look at is Paul Klee, one of the Bauhaus’s two main artists. In the 1920s, Klee was creating what we would now call generative art, i.e. rather than painting in an expressionistic way, he would set up quasi-rules for himself such as making lines on paper out of which a figure emerged. This was very much the kind of thing you could dispassionately program with a computer. But what Klee and others at the Bauhaus were teaching was a holdover of expressionism that had strong spiritual components; they were by no means trying to fully rationalize this material.

Between the 1920s and the post-war period, many avant-garde figures emigrated from Europe to England. After two world wars, people no longer believed in the utopian ideals associated with modernism, but some still saw potential in modernism’s artistic practices of one kind or another. One group saw themselves as inheritors of the techniques used by Klee and took out what they considered their delusional politics, and wrote algorithms to produce the same kind of paintings. They had politics of their own, though—technocratic politics. They wanted a rational, technocratic designer instead of a delusional “genius” figure. It was this kind of artistic-formalist milieu from which the first computer architecture emerged.

This challenges the dominant narrative that architects “discovered” computers in the 1990s.

The digital architecture that is easily traced back to the 1990s is well within the old-fashioned “genius” mentality of architecture, and it’s convenient for certain architects who want to claim the computer as their own. But this other tradition happening in the immediate post-war period was spread very widely among architects, though generally not the principals of firms. Rather, it spread to architectural technicians—people using computers in the back offices of big corporate firms, or computer consultants who are architects—not people designing fancy buildings. It’s completely continuous from early 20th-century modernism to today, but the thread gets lost in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s.

While some may think they’re designing in a 19th-century manner, the way architecture is being created is part of this long series of computational programming changes. It’s just hard to be aware of that.

The people in those back offices are not often recognized, and certainly not in conversations about architecture by those outside the field.

Invisible labor and not valorizing collective labor enough are big problems in architecture right now. The pervasive, compelling myth still exists that someone called an architect designs a building; he might hire some people to draw it out for him or write up the details, but the idea belongs to this “genius” figure. Yet anyone who has worked in architecture knows a lot happens below that top figure, and maybe most of the design decisions and meat of any project come from below. It’s the same in most professions. But even knowing this, students aren’t given enough awareness of other figures who they can see as role models or alternative methods they can see as valuable. A big part of my work involves building up a whole cast of characters, including back-office computer technicians, and a whole repertoire of techniques that architects can see as their own so that they don’t feel inferior.

There are levels to invisible labor, too. The computer-using architect, for example, still has computer programmers below them who become invisible. One reason this happens is because it’s convenient to package all this invisible labor so that it can be marketed and sold. If you’re a firm like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), you can’t show all the messiness of computation; you have to create an image of computation and sell that to clients.

Have you found anything that makes that labor visible?

There are loopholes and short circuits that subvert this structure, when something from a particular lower level asserts itself at a higher one. Look at the iconic Hajj Terminal in Saudi Arabia by SOM (1981). It looks exactly like the screenshot of a sort of output made by form-generating software that an engineer designed in the 1970s. For a historian or theorist, it’s a teachable moment when a charismatic, iconic building expresses something buried deep within the labor hierarchy. And it wasn’t even the sub-consulting engineer himself who revealed this hierarchy but the piece of software he wrote.

This pushes against the notion that the computer is just a tool.

It’s a comforting myth that the computer showed up and architects continued to work the same way they always worked; in fact, a lot of empirical evidence indicates that when computers show up, things change.

The question is, How do you talk about causation? Maybe the most helpful way is discussing what the computer is resonating with and enabling around it. When the computer first arrived on architects’ desks in the mid-20th century, the idea of the computer was much more specific than just a generic tool or drafting table. It was the structuralist device that could shuffle around symbols and create generative art in a tradition of abstraction. It was also very good at creating concrete poetry.

For me, the prototype of the computer for architects was László Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator, which is a device that generates environmental effects. Some of the earliest computer-using architects wondered how this kind of effect generation could be systematized and organized. Marshall McLuhan, for example, dreamed of creating a room at the University of Toronto in which any environment from around the world could be recreated with screens, sounds, and smells with a computer.

That was the computer that these architects were dreaming about. It was a very particular device to be used to very particular ends. And it was no surprise that this resonated strongly with postmodernism, which was concerned with the codes buildings embodied and the idea that you could come up with the linguistic code of a building and parametrically recreate it in different forms.

Le Corbusier, you argue, in many ways exemplified this slow creep of architecture-becoming-programming. How so?

What connects the two is the particular, structuralist idea in Western philosophy since the 19th century that cultures are made up of codes—that there’s a linguistic underpinning to them. So to understand another culture you would work as an anthropologist to decode the meanings of different things in that culture. This is what Le Corbusier took up. Being a visually oriented person, he saw the vernacular objects in Eastern Europe as speaking the culture. In other words, the culture flows through the person who made it into the object and back out to the people who come into contact with it. The idea was compelling to him because he believed Europe was losing its culture to industrialization, that all these meaningful objects were being replaced by generic ones. Part of his project was to reimbue meaning into the object or make it more artistic. At the end of the day, this cast the architect as someone attuned to these codes. At a place like the Bauhaus, it became a collective computation project.

Just like the functionalist architect, the computer programmer works with a set of codes and creates appropriate outputs without ever creating something new. It’s more about channeling forces through codes into a set of objects that have their own effects. The radical anti-authorial/anti-genius architect stance comes in here, too.

I see Le Corbusier’s purist painting, in which there is a set of industrially created objects which sort of communicate with each other and with the viewer, as exactly what computer scientist Alan Kay argued regarding object-oriented programming and computation works. It’s all about setting up a bunch of objects in communication with each other. That’s all the programmer does, that’s all the architect does, and it’s all the artist does. There’s no creation. It’s juxtaposition. There are no longer authors or “geniuses,” there are only technicians.