How Bio-Based Building Materials Are Transforming Architecture

A colorful grid of bio-based tiles rests atop a black surface. Created as sustainable alternatives to products ranging from acoustic cladding to frosted glass, the tiles derive from eggshells, expired lentils, and other green waste. These palm-sized squares, despite their origins in food scraps, invite tactile investigation. The same lure emanates from a neighboring rug swatch woven from Abaca fiber; a masonry-like block composed of sugarcane; and textile strips made from apple pomace. This enticing display accompanied “Material Time,” a day-long symposium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design held in mid-April that explored our emerging relationship with bio-based materials.

Amelia Gan (MDes ’23) organized “Material Time” in her capacity as the GSD’s 2023–24 Irving Innovation Fellow. She collaborated with Ann Whiteside, Assistant Dean for Information Studies at the GSD, and Margot Nishimura, Dean of Libraries at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), who had previously cofounded Material Order , a knowledge-sharing resource for design materials collections in academic libraries. Conceptualizing the symposium, the three organizers identified practitioners, researchers, and educators at various stages in their careers whose work touches on design scales from microbes to building systems to outer space. The resulting discussion foregrounded the urgent need for transformations in how we think about and interact with the materials that comprise our built environment.

Concrete, aluminum, and steel rank among the most prevalent materials in contemporary construction. They are also quite costly in terms of their environmental toll. Developed from dwindling non-renewable resources, such conventional engineered building products inflict widespread ecological harm, from their extractive, carbon-intensive manufacturing processes to their final disposal in landfills where they languish, leaching pollutants into the earth. Bio-based counterparts offer a potential alternative to these destructive materials.

In her introductory remarks to the symposium, Gan announced that the time has come for design professionals to “critically rethink our material choices.” Indeed, “the prevailing ethos, which celebrates idealized, unchanging form, finds itself at a crossroads challenged by materials sensitive to environmental changes,” Gan continued. “How do we reconsider the way we represent and construct our environment?” Fortunately, bio-based materials offer a compelling lens through which to reexamine construction techniques as well as expectations about how materials look and what they can do.

Consider bacterial biocement, as fabricated by Laura Maria Gonzalez, founder of Microbi Design and former researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab. Utilizing computational design and 3D printing, Gonzalez creates sculptural molds infused with sand and bacteria. As the microbes are fed, the mixture hardens into solid forms that, with continued nourishment, become stronger over time. If fractures occur, these living bricks heal themselves through microbial growth. They may even be programmed to signal, through a change in color, the presence of environmental toxins such as lead or arsenic. For Gonzalez, bacterial biocement promises more than a sustainable replacement for more carbon-intensive materials; it presents an opportunity to think about “how we integrate these organisms as living systems to engage more deeply with our environment.”

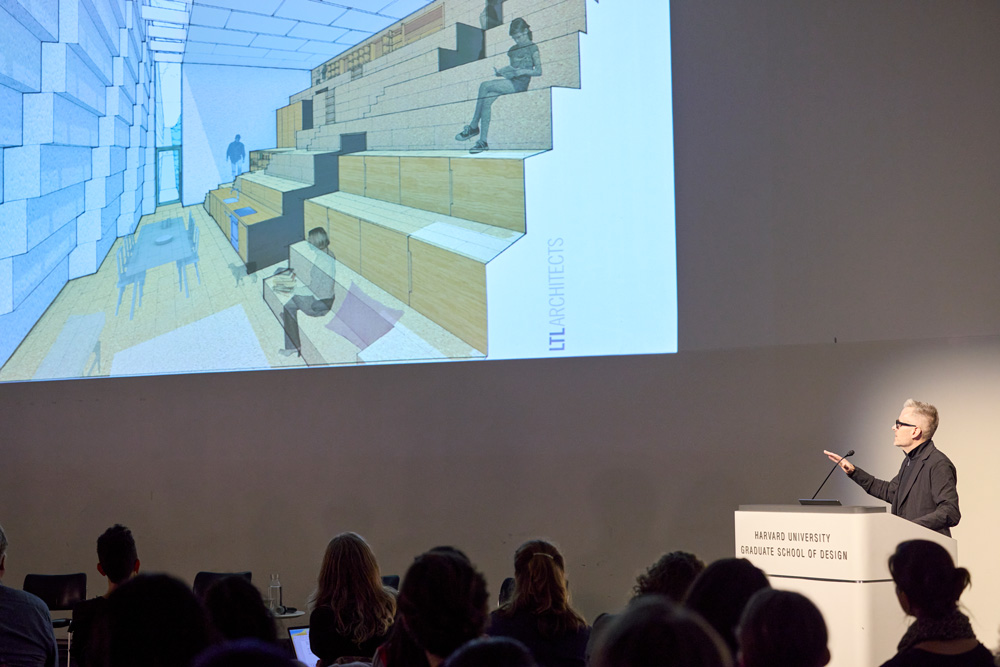

Paul Lewis, principal of LTL Architects and Professor at Princeton University School of Architecture, emphasized a different behavior we could seek from bio-based materials—that of performing multiple functions. As opposed to aggregated thin, lightweight, single-use products that comprise the typical modernist building section—structure, insulation, waterproofing, and so on—Lewis has experimented with using straw in bale-like configurations that act simultaneously as insulation and load-bearing structure, from which space can be carved. Lewis advocated embracing ideas that are “fundamentally at odds” with the “given values we’ve inherited from modernism,” aligning his explorations with the growing recognition that buildings as constructed throughout the past century have played a significant role in our current ecological predicament. John May, cofounder of MILLIØNS and Associate Professor of Architecture at the GSD, echoed this sentiment as he characterized the term, and the very concept of, “waste” as a vestige of a past industrial capitalist era. Rather, that which has been previously seen as waste should now be embraced as raw materials for other processes.

Underscoring the significance of terminology, Lola Ben-Alon, Assistant Professor and Director of the Natural Materials Lab at Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (GSAPP), cautioned that “bio-based” materials are not necessarily less extractive or energy intensive than conventional materials. To ascertain environmental impact, she advocated examining a product’s entire life cycle, with a focus on a system’s inputs and outputs. “How are these bio-based materials produced?” Ben-Alon asked. “And where? What are the processes involved in the extraction of these materials? Where are they extracted? And can we pose other means or methods of locally creating these materials?” Such systems thinking—understood as a holistic approach that views component parts in relation to the broader dynamic systems to which they belong—emerged throughout the symposium.

For example, systems thinking came to the fore with Lina Ghotmeh’s presentation, which focused on her design firm’s use of bio-sourced materials. Ghotmeh—currently Kenzo Tange Design Critic in Architecture at the GSD—featured the recently completed Hermès Maroquinerie de Louviers, a leather workshop constructed with locally manufactured low-carbon bricks that showcase the skill of Normandy’s brickmakers. This project is the first industrial building to earn the French E4C2 label, denoting the country’s highest recognized levels of energy efficiency (it is a positive energy building) and operational efficiency (in terms of carbon footprint reduction).

Drawing on concepts resonant with systems thinking, Martin Bechthold, Kumagai Professor of Architectural Technology and Director of the Material Processes and Systems Group (MaP+S) , discussed the iterative processes of science and design, highlighting their similarities and differences, particularly that designers tend to work at a larger scale. And later, Pablo Pérez-Ramos, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, expanded the conversation beyond our planet with a consideration of thermodynamics and ways in which these universal laws may help us grapple with conditions of extreme heat in certain landscapes.

Yet another instance of system thinking emerged in the position of Jennifer Bissonnette, Interim Director of RISD’s Nature Lab, who called for “artists and designers to have a certain level of eco literacy.” Design programs, Bissonnette argued, have a responsibility to “turn out people who have a sense of how ecosystems function,” the “cycles, flows, nested systems, development, dynamic balance” that serve as “organizing principles of the natural world.” Likewise, she advocated that scientists be schooled in studio methodology and design thinking to broaden their investigative repertoires. Such pedagogical shifts would go a long way in facilitating the multidisciplinary cooperation—from conceptualization and experimentation through scaling up to real-world manufacturing and application—that bio-based materials necessitate.

Reflecting on “Material Time” a few weeks later, Gan reiterated the need to overcome disciplinary silos. “These conversations shouldn’t happen in a vacuum, yet that often tends to occur,” especially when operating in the complex realm of bio-based materials, which encompasses design, biology, engineering, politics, ecology, sociology, and more. “The challenge is,” Gan continued, “how do you move from a high-level conversation to productive action?” Formulated to further interdisciplinary and intergenerational discussions within the GSD and beyond, “Material Time” offered an exemplary step in the right direction.

What Oysters Can Teach about Life in the Climate Crisis

On the southern coast of Taiwan, groundwater pumped from the earth flows through dense tangles of pipes to supply industrial-scale fish farms. This intensive aquaculture has had a dramatic effect on the surrounding land of Pingtung County. Daniel Fernández Pascual, winner of the 2020 Wheelwright Prize, noted that the pumping of groundwater has caused some areas to sink 6 to 8 centimeters each year. Speaking at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in March, Fernández Pascual described how “buildings keep losing their ground floors. Living rooms become garages. Doors become stairs. Roofs touch the street.”

Taiwan’s fish farms exemplify the “extractivist” logic of aquaculture—and its long-term consequences. Pingtung County is one of the areas that Fernández Pascual studied during his Wheelwright term, which brought him in contact with coastal communities in ten countries, from the Isle of Skye in Scotland to the shores of Chile to coastal towns in China. The $100,000 award enabled him to take a global perspective on the risks of intensive aquaculture while identifying alternatives that could become the basis for a sustainable future. Resisting extractivism, Fernández Pascual aimed to foster a “tidal commons,” which he defined as a “framework of shared assets and shared stewardship of ecological structures in the planet’s shoreline.”

The title of Fernández Pascual’s talk, “Being Shellfish: Architectures of Intertidal Cohabitation,” reflects the central place of oysters, mussels, scallops, and other bivalves within his vision for the tidal commons. “Oysters filter the sea,” he said, “and in so doing their shells record histories of coastal habitation as material witnesses of the Anthropocene.” The natural habitats of these creatures comprise the same coastal regions that fish farms can spoil. “Bivalves and other foods have been a tool for us to understand the impact of intensive food production,” Fernández Pascual said, “while also supporting the different struggles and solidarity networks across communities in the ruins of extractivism.”

The scope of Fernández Pascual’s research extends far beyond encouraging the consumption of more ethical seafood—though bivalves are indeed tasty, sustainable alternatives to farmed fish. At the GSD, he put forward a holistic vision for new models of economic development and strategies for navigating a changing climate. In addition to rethinking food supply chains, bolstering restaurant menus, and undertaking educational initiatives, “intertidal cohabitation” means harvesting resources, such as shells and seaweed, that have long been used in traditional building practices and imagining new uses for them in the present.

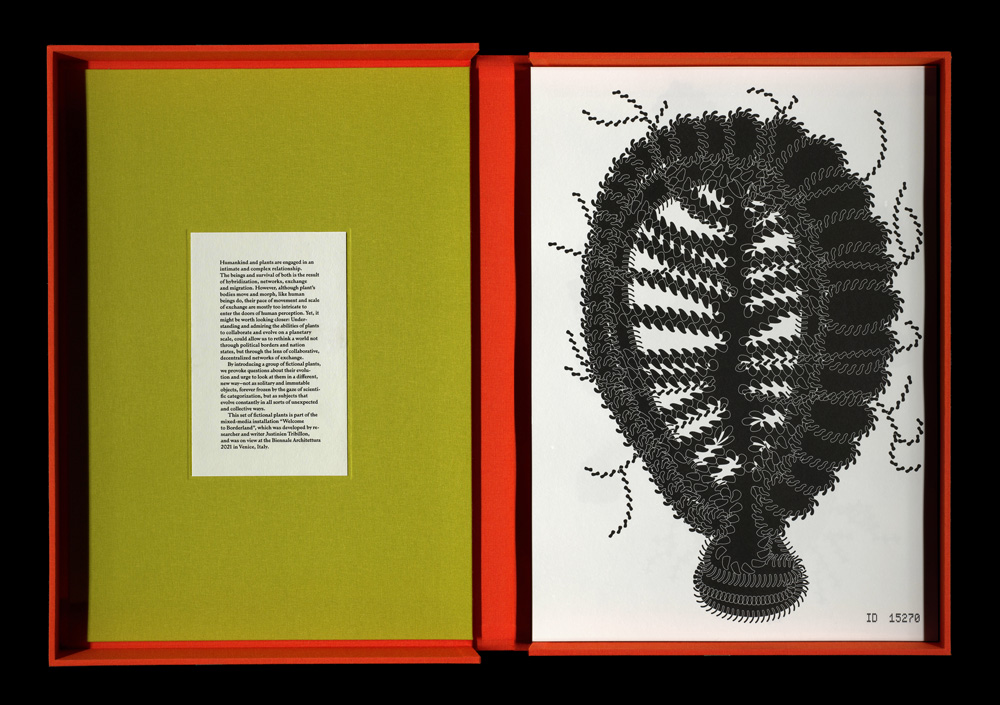

Fernández Pascual may be best known for his collaborations with Alon Schwabe as Cooking Sections. Their work, often featured in international biennials, includes performative meals that foreground urgent ecological questions. CLIMAVORE, one of their research initiatives, aims to “transition to alternative forms of nourishment in the climate crisis.” In 2017, ATLAS Arts, a cultural organization based in Skye, Raasay, and Lochalsh in northwest Scotland, invited Cooking Sections to the area, where salmon farming dominates the local economy. Fernández Pascual and Schwabe developed a project that eventually became a long-term engagement with the community. One aspect of their work is an installation constructed from metal oyster cages. Built in an intertidal zone, the structure is submerged at high tide and inhabited by bivalves. At low tide, it becomes a communal table for the performative meals that Cooking Sections organizes as well as a public forum for discussions and workshops.

One fundamental question raised at these forums is how the economies of Skye, Rassay, and Lochalsh might transition away from fish farming. Enhancing the role of bivalves in the food supply chain is part of the answer. At the GSD Fernández Pascual also highlighted potential uses of oyster shells as building materials. He has been collaborating with a team to create tiles from oyster shells that have been cleaned, ground up and processed. A pair of murals depicting bivalves that he and Schwabe created demonstrate the potential of this material. They employed similar techniques for Oystering Room (2020), their contribution to the 2020 Taipei Biennial. Visitors to the installation could recline in lounge chairs crafted in a material inspired by a Taiwanese technique of mixing oyster shells, glutinous rice, and maltose sugar to create a binding paste. Visitors could also sample an exfoliating skincare product derived from oyster shells—a luxurious demonstration of how bivalve cultivation could counter the sinking economics of fish farming.

Oyster shells have long served as a source of fertilizer and as a key component of tabby concrete. Fernández Pascual surveyed building traditions in Southern China, where oyster shells are employed directly as siding, as well as in Japan, where walls made of oyster-derived plaster keep interiors well ventilated. Seaweed harvested from intertidal zones has also served as roofing material in Denmark, China, and elsewhere. In revisiting these traditions Fernández Pascual was not attempting to recover a lost pastoral ideal. The goal is “cohabitation” in the present, a concept that challenges us to “learn how to produce an ecological future that enables us to live well beside toxicity and unstable, shifting seasons.”

In gathering information from around the world, Fernández Pascual also facilitated a global exchange of information about what learning to live beside toxicity might mean. “Research conducted as part of the Wheelwright Prize has tied together different experiences from communities dealing with pollution from intensive farming,” he said, emphasizing how these communities were interested in “sharing lessons on collective usership of the coast and architectures of intertidal stewardship and resistance.” While the Wheelwright Prize supports such an international outlook, Fernández Pascual’s award was announced just as the world shut down due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Speaking about his research process prior to his public talk, Fernández Pascual noted the importance of local collaborators, many of whom he contacted remotely. “Especially when we’re talking about extractivism,” he said, it’s vital to ensure that you “don’t become extractive in the research.” The ethics of working as “the outsider coming to learn,” especially during the pandemic, were at the forefront of Fernández Pascual’s process.

The pandemic also altered the focal point of the project. Initially, Fernández Pascual and Schwabe envisioned restoring a building on Skye that could serve as a permanent hub for their Climavore work. Yet with rural real estate in high demand, the project fell through. This shift proved fortuitous, however, allowing the project to take the form of an “assemblage of formats” that span different practices and fields of knowledge while engaging a wider range of stakeholders, from educators to activist groups to chefs. “Precisely because we did not have to take care of a building,” he said, “we could rethink allyship and make the project much more open and diverse.”

This fluid approach also forced Fernández Pascual to take an expansive view of his own role as a designer, researcher, artist, and activist. He described learning “how to jump boundaries across disciplines, especially when talking or thinking about the food supply chain.” His research incorporates vernacular techniques and technological innovation in material projection. “There are many networks of knowledge involved in figuring out what it means to live besides toxicity and to imagine an alternative scenario,” he said, encouraging design students in particular to look beyond their disciplines to “find the necessary allies to join in the quest for alternatives.”

From Drought to Flood: Solutions for Extreme Climate Events in Monterrey, Mexico

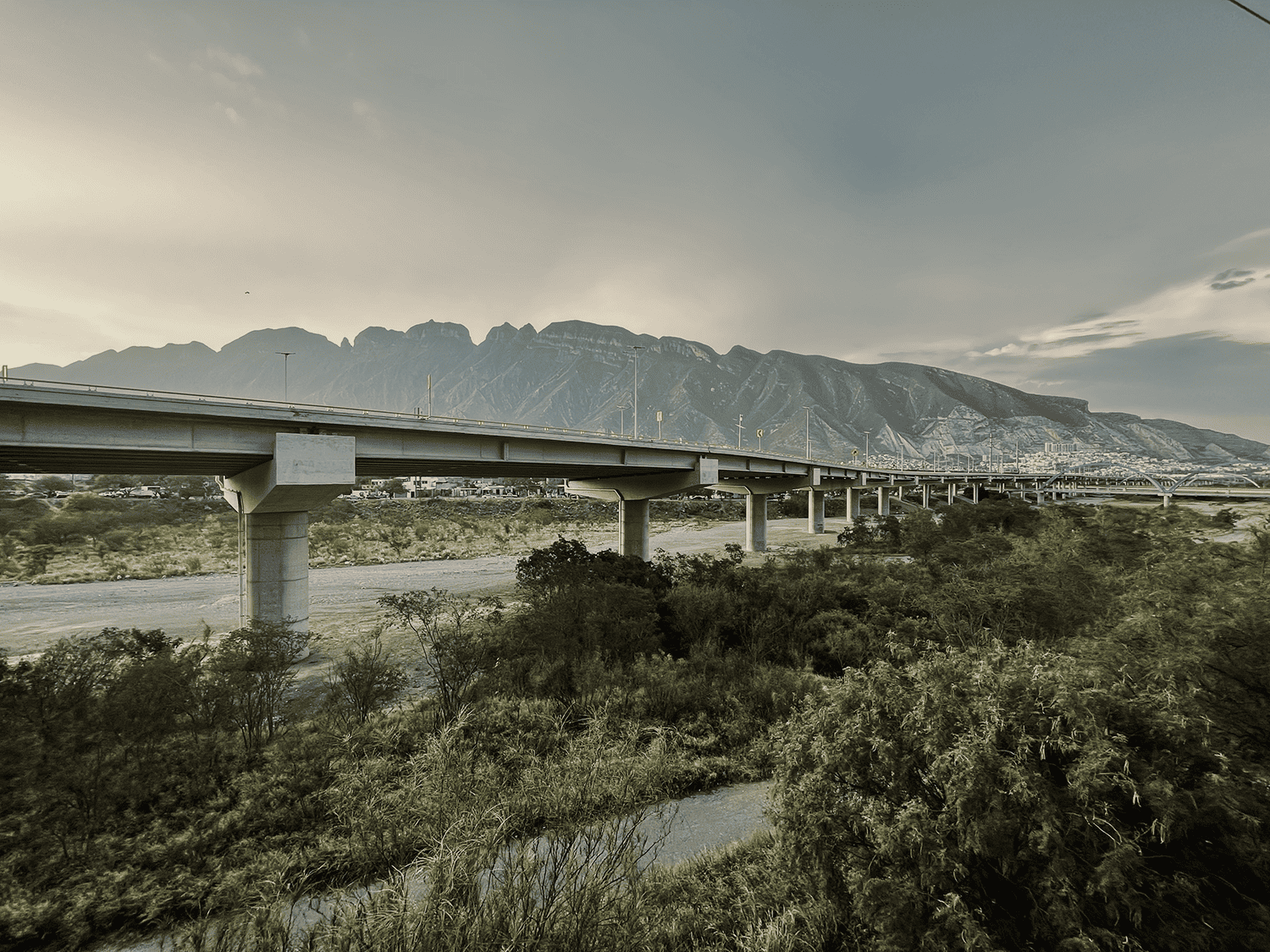

In 2022 and 2023, Monterrey, Mexico’s second largest city, experienced a critical shortage of water and, like Cape Town in 2018, was close to a Day Zero of water provision. The emergency made international headlines , as the state government rationed water for many of the city’s five million residents. While struggling at times to supply water to residents, Monterrey is also well-known for its severe floods that have peaked in intensity during deadly hurricanes, such as Gilbert in 1988 and Alex in 2010. In recent years the fluctuation between these extreme events has been intensified by a changing climate.

Like many other cities, Monterrey is not prepared for a warming planet with increased volumes of water in its atmosphere and extended droughts. The impervious urban ground that covers much of the city is designed to drain water as quickly as possible. Agriculture, industry, and citizens overexploit water unsustainably. As a result, during much of the year the Santa Catarina riverbed remains dry. Yet at times of heavy rain, it is prone to overflowing, with potential catastrophic results.

In the fall 2023 studio “AQUA INCOGNITA: Designing for extreme climate resilience in Monterrey, MX,” GSD Design Critic Lorena Bello Gómez worked with students to devise design strategies along the Santa Catarina watershed to increase water security and to reduce flood risk. Bello was invited to Monterrey after her work on the first iteration of AQUA INCOGNITA, in 2021 and 2022, which focused on the Apan Plains, a region that shares a basin with Mexico City and also struggles with its water supply.

For Bello, every studio is an opportunity to expose students to real-world climatic problems and inspire efforts to restore a lost balance with the water cycle. “Traveling with students for field research and engagement is a fundamental part of the pedagogy,” she explained. “The territorial scale of a project dealing with water risk in an urban region through the lens of an urban river, requires the ability to constantly telescope from macro to micro scales.” According to Bello, digital tools like Google Earth and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) cannot recreate the experience of “inhabiting and crossing the river with your own feet to understand its ecology and scale, and that of its surrounding infrastructures.”

Bello’s focus on the Santa Catarina River watershed developed through a yearlong engagement with the regional conservation institution Terra Habitus , which sponsored the studio. In addition to giving students firsthand experience, Bello’s studio was also an opportunity to help those fighting to change the status quo on the ground. “Deciphering where to insert the needle in this impervious skin is the first incognita to solve,” Bello said. “We know that there is the potential to recover this river as an ecological corridor and climate resilience infrastructure for the city, but we also need to know that there are local academics, organizations, and citizens that could benefit from our work to push the political will.”

Bello’s fieldwork in advance of the studio included meetings with a variety of stakeholders. She gathered input from representatives of community groups and planning agencies as well as political leaders such as Monterrey’s mayor, Donaldo Colosio, and the mayor of neighboring San Pedro Garza García, Miguel Treviño. She also met with Juan Ignacio Barragán, the director of the local water operator Servicios de Agua y Drenaje de Monterrey. Other important preparation included a Spring 2023 research seminar, “Resilience Under New Water Regimes: the case of Monterrey Day-Zero”, supported by PhD candidate Samuel Tabory (PhD ’25).

Daniella Slowik (MLA II ’24) chose to take the studio because she is already focused on climate- and water-related projects and sees herself working on these topics after she graduates. “Different parts of the world are going to continue to experience massive extremes,” she said, “and we have to learn how to work within those constraints in our design field.”

Students toured the riverbed with two local conservation groups as soon as they landed in Monterrey. They examined the soil and plant life in a dry section of riverbed running along one of Monterrey’s major highways before visiting Los Pinos, an informal settlement along the river. Locals shared memories of playing soccer, riding motorbikes, or attending parties on the riverbed, but they also expressed their new understanding of the river as a unique healthy ecology in otherwise desertifying Monterrey. The value of being on the ground, as Bello said, was in “sensing citizens’ empathy towards its river when they walk with us, learning about agricultural practices in the mountains, or understanding from local experts on policy and cultural challenges to overcome.” She continued, “This physical and personal exchange propels students’ imaginations, while their questions make locals aware of hidden aspects that they were overseeing.”

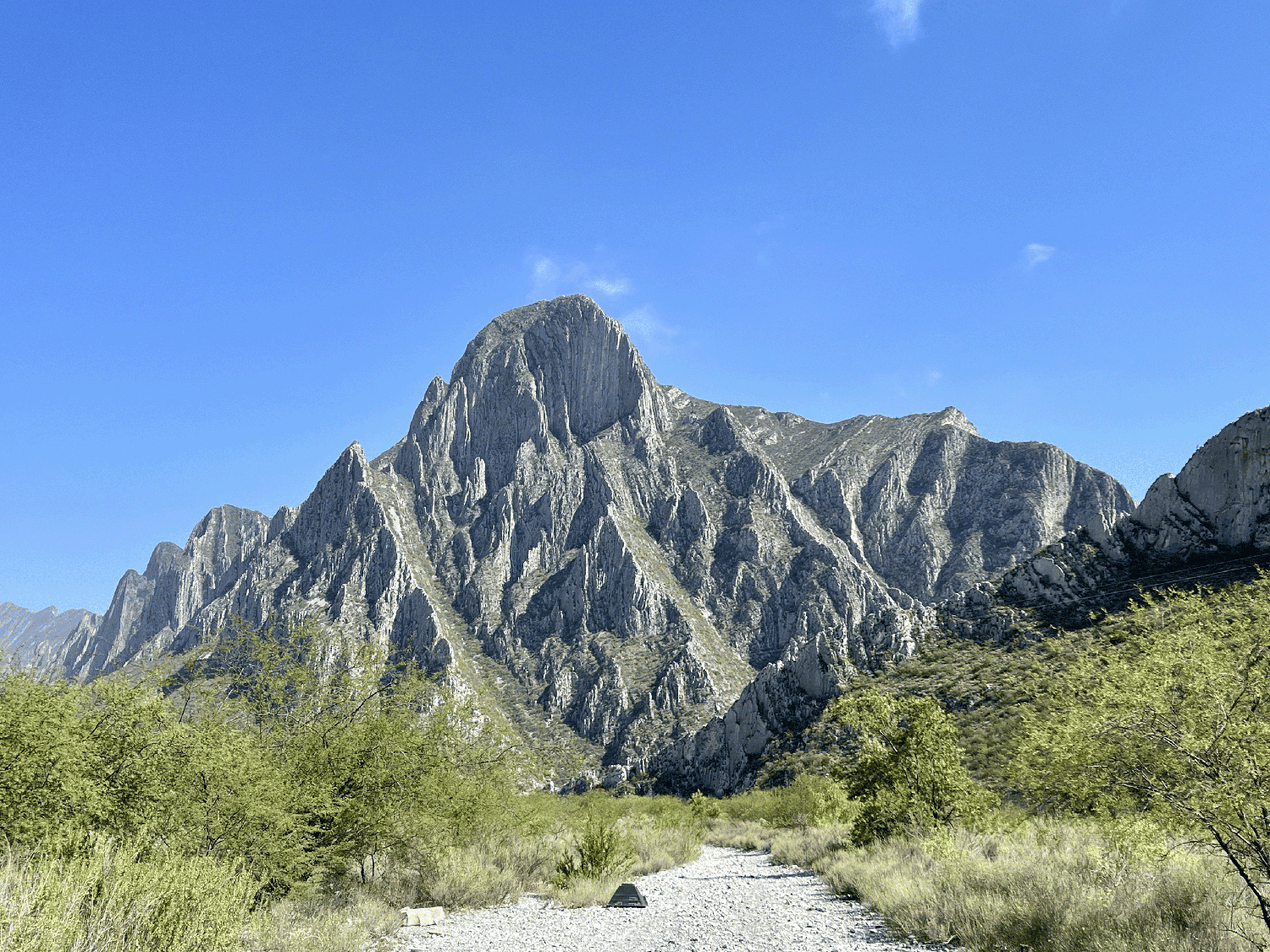

The group later drove to La Huasteca, the first canyon in the Parque Cumbres National Park in the nearby mountains that is the source of the Santa Catarina. The area has also become a site of unregulated settlements despite its protected status. “Traversing the lengthy river,” Bello explained, allowed students to “understand the duality between its urban condition downstream—today a flood-control channel—and its powerful upstream condition along the monumental Huasteca and Cumbres National Park, or by its flood control dam Rompepicos.”

The studio also spent several days participating in the Urban Hydrological Adaptation symposium and workshop sponsored by the Tecnológico de Monterrey with GSD former graduate Ruben Segovia (MArch II ’17). Organized by Bello and Segovia, the gathering of architects, landscape architects, and other academics built on conversations she had at the Tec de Monterrey on her previous fieldwork visits. Over the course of several days, students presented case studies of other cities with rivers that they had prepared earlier in the semester.

Several afternoons were devoted to site visits to locations ranging from parks such as the upscale Paseo San Lucia, an artificial canal offering boat rides, to Centrito, a neighborhood in the process of being rebuilt, where the group navigated several blocks of construction sites in 95-degree heat. A highlight that was both fun and educational was a hike in Chipinque National Park, which offered breathtaking views of the Sierra Madre Oriental and the ability to view the city within the context of the mountain landscape.

Inspired by the knowledge gleaned from the site visits and motivated by meetings with representatives from the municipalities of Monterrey and nearby San Pedro to address urgent needs, students’ final projects displayed a variety of alternative futures for the Santa Catarina River. While working individually, they also tackled collectively the myriad of challenges to overcome at the Rompepicos flood control dam, at the Cumbres National Park, and along the Santa Catarina River from the Cumbres to the urban park Fundidora. The final projects displayed a wide variety of solutions. Some students chose to center their work on the mountainous area around La Huasteca; others took as their focus the highways or parks closer to the urban center. (See an overview of the projects below).

As climate change becomes an unavoidable concern in the design disciplines, the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture has pledged its “abiding commitment to climate mitigation and adaptation through its curriculum, faculty research, and design culture.” Indeed, many students cited the urgency of climate change as a primary reason that they chose this particular studio. Bello’s career has also focused on climate. In addition to her previous research in Mexico, she has used her background in landscape, architecture, and urbanism in her work with environmentally vulnerable communities in India, Colombia, and Armenia. Weather permitting, she says with a smile, she plans to expand the Monterrey studio next fall.

For the final review, students presented their work in a sequence arranged geographically along the river transect, presenting the different challenges and opportunities to overcome by design such as:

Reciprocity at Cumbres National Park

- Jianing Zhou (MLA II ’24)’s project proposes an alternative network of almost invisible “incognito dams” as a counterpoint to mega-projects meant to control flood risk

- Emily Menard (MLA II ’24) explores reciprocal relationships between those who visit and inhabit the park, towards a more mutualistic and regenerative land use for water conservation

The ephemerality of flooding

- Lucas Dobbin (MLA I AP ’24) created “room for the river” at a key bend and point of risk inflection for extreme water flows entering the city from Parque Cumbres

- Pie Chueathue (MLA II ’24) uses the time in between floods to introduce a temporary/light-footprint tree nursery to promote urban tree canopy and work

Vertical and horizontal capillarity

- To reduce flood risk in the larger watershed, Boya Zhou (MLA I AP ’24) proposed starting to recover the network of streams while reconnecting them to the urban fabric

Circularity

- Responding to the near-shoring boom in Monterrey, Sanjana Shiroor (MAUD ’24) explored principles of circularity for brownfields along the river’s corridor to counter low-density sprawl

Bridging and descending to bring the edge of the city to the river

- Ashley Ng (MLA I ’24) designed a promenade

- Sophie Chien (MLA I AP/MUP ’24) proposed an inhabited bridge

- Using bridges as a river entrance to descend to a newly terraformed riverbed, allowing for habitat and inhabitation between storms, was the design vision of Annabel Grunebaum (MLA I ’24), Miguel Lantigua Inoa (MArch II/MLA I AP ’24) and Bernadette McCrann (MLA I AP ’24)

Climate justice

- Daniella Slowik (MLA II ’24)’s project emerged from a deep engagement with the history of Independencia, a marginalized community near the river, and asked what it would mean to convert the river into a community asset rather than just a source of vulnerability and risk

A New Future for a Colonial Fort in Ghana

The village of Ada Foah sits on the coast of Ghana where the Volta River flows into the Atlantic. Its name—a centuries-old vernacular adaptation of “fort”—acknowledges an erstwhile landmark: Fort Kongenstein. Constructed by Danes in the eighteenth century, Fort Kongenstein facilitated trade in goods and, for a period of about a decade, enslaved people. It is one of many such forts erected on the West African coast by European traders and settlers. These foreign structures, often built from materials imported from Europe along proto-globalized trade routes, stand as remnants of the complex and brutal colonial history that has shaped the region.

Though other forts in Ghana, such as Cape Coast Castle, have been preserved and rehabilitated, Fort Kongenstein today is at risk of being forgotten. Its historical significance is belied by its current physical condition. Most of the original stone fort has washed into the ocean, destroyed by the severe coastal erosion that has accelerated in a changing climate. What remains of the site includes a trading post, built in concrete and timber sometime after the British took power in the area, as well as a brick residential structure for the fort’s captain. In recent years, members of the Ada Foah community have taken steps to reclaim the site, adorning its walls with murals and occasionally hosting cultural events in the ruins.

While the fort has fallen into disrepair, tourist facilities and villas have sprung up in the area, catering to those drawn to the area’s natural beauty and seeking respite from the bustling capital Accra, a three-hour drive away. Caught between tourist development and relentless coastal erosion that has only accelerated with climate change, Ada Foah’s namesake has an uncertain future.

Yet this uncertainty also presents opportunities to transform the site into a facility with contemporary meaning. “Forgotten Fort Kongenstein,” an option studio led by Olayinka Dosekun-Adjei, John Portman Design Critic in Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, challenged students to grapple with the compound’s past while envisioning a new future for it at the heart of the Ada Foah community. Dosekun-Adjei, a Lagos-based architect and Creative Director of Studio Contra , aimed to embrace the fort as a “symbolic site of contact between European settlers and traders and the local population,” rather than “rejecting the ruins as part of a painful past and contentious or problematic history.”

With support from the Open Society Foundations, Dosekun-Adjei led a group of students on a trip to Ghana to study the site. In addition to proposing an adaptive reuse of the fort structures that would address unforgiving erosion, students were tasked with developing a cultural program for the adapted site that would be historically sensitive, relevant to Ada Foah residents, and connected to the burgeoning ecosystem of regional arts institutions. Instead of preserving a monument or recovering a ruin, the goal was to transform the existing conditions into what Dosekun-Adjei calls a “generator” that will enrich the cultural life and economy of its surrounding community.

We used a European building constructed in Africa as a site for hybridizing what could be a rediscovered Indigenous approach to architecture and material culture.

Olayinka Dosekun-Adjei

“When we first arrived at the site after a long drive, the sun was blaring, but it was beautiful,” recalled Mariama M. M. Kah (MArch II ’24). “Everyone was taken aback by the sensory and auditory experience: wind gusts were coming off the Atlantic, the air was full of sea salt.” This stunning setting also posed challenges for envisioning resilient material conditions for the studio project. Fort Kongenstein has been worn down over time, defined today as much by absence as by monumentality.

Kah, who had worked in Ghana prior to studying at the GSD, described the fort as a palimpsest characterized by a “layering of history.” The structures that remain embody historical discontinuities: the captain’s house, the oldest extant structure, is built of brick imported from Denmark. The concrete trading post, meanwhile, was constructed sometime after 1850, likely when the British dominated the area. Timber used in each structure has mostly rotted away or been repurposed elsewhere. Recent paintings on the structures’ walls are evidence of community-driven attempts to discover meaningful uses for the building.

Dosekun-Adjei views these challenging conditions as an impetus to critically evaluate the contemporary West African architecture. “We used a European building constructed in Africa as a site for hybridizing what could be a rediscovered Indigenous approach to architecture and material culture.” Looking at the historical fort through the lens of globalization also offered a genealogy of contemporary practices in West Africa, “where so many materials are produced elsewhere, imported very much like this building.” Tracing the histories of these practices back to colonial periods can help architects today rediscover materials and techniques that retain deep local meaning precisely because of their hybridity.

In guiding students through their studio projects, Dosekun-Adjei encouraged them to take imaginative approaches to this hybridity while also foregrounding the need for resiliency. “The idea of a museum or an archive became complicated because we were situated right in front of the sea and coastal erosion was happening at such a rapid rate,” Kah said. “The inevitable reality was looming: the site would succumb to the Atlantic.” Some projects accepted this reality by envisioning temporary structures that would last only as long as the terra firma. Kah addressed this challenge by proposing a robust sea wall structure that would be the centerpiece of similar measures developed in the area.

Courtney Sohn (MArch I ’24) also envisioned a permanent cultural center on the site. “I was thinking about materials in relation to temporality,” she said. “We projected a future for the site in which the materials were going to fall into the ocean. I wanted to build in materials that had resilience even if the rest of the site was lost.” That meant employing techniques from marine architecture to create a structure over the site. As the sea approached, the historical fort would be washed away, representing “a part of the history that we could let go of,” while the new structure, with its new community-centered purpose remained.

The historical legacy of the fort, as Dosekun-Adjei sees it, could help create needed public spaces and institutions in Ada Foah, a village dominated by private tourist development. A re-imagined fort complex could transform Ada Foah into a new kind of public space: a cultural center in the community and a node in the emerging network of small cultural institutions in Ghana. To generate ideas for the building’s program, studio participants visited a number of arts organizations in Accra. With little government support for the arts available, institutions like the Dikan Center and the Nubuke Foundation Art Gallery depend on the ambition and vision of future cultural leaders. This ethos is reflected in the physical structures that house many new arts organizations, many of which employ strategies of adaptive reuse. The Dikan Center, for example, is a photography gallery and library in a refurbished housing complex.

Many of the arts organizations that inspired student projects had hybrid identities, offering their communities more than spaces to contemplate visual arts. The Nubuke Foundation complex is a mix of exhibition galleries and studios, co-working spaces, and other facilities intended to provide broad support for the creative economy.

Partly in acknowledgment of this local need and partly as an exercise in working with different architectural scales, Dosekun-Adjei prompted students to envision both exhibition spaces and other facilities for the community such as classrooms and workshops. Inspired by the role of film production in decolonizing struggles, Kah proposed a program for the fort that included an art house cinema. “I looked at photography and cinema as both a decolonizing method as well as a method for people [in West Africa] to construct their own narratives and archive their history and memories. Photography and cinema are a means of creating beautiful dialectic stories that span generations but still hold true.” Sohn drew upon course discussions about cultural restitution—the repatriation of artifacts removed during the colonial period—as well as her conversations with Ada Foah community members to propose a space for archaeological finds that could stimulate historical and cultural research. Other projects included spaces for a community radio station and production facility, as well as art galleries, classrooms, and workshop spaces.

The GSD student projects, compiled by Dosekun-Adjei and her studio, will become part of a discussion with local leaders and potential funders about the future of the site. The work undertaken as part of the GSD studio suggests that the future of Fort Kongenstein will exemplify an expanded notion of adaptive reuse. Any project that modifies the ruins of the fort will have to address questions of sustainability while engaging with contested historical narratives. As Dosekun-Adjei says, the project will “uncover histories, both architectural and material,” providing new foundations for building in the region and beyond.

Boston Mayor Speaks at the GSD about Urban Forests, Community Resilience, and Environmental Justice

Describing herself as an avowed “tree hugger” from her childhood as part of an immigrant family, when a beloved tree afforded her a sense of peace, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu offered a forceful vision for the role of urban forests in her city’s push for environmental justice and climate resiliency. In the packed Piper Auditorium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Mayor Wu spoke of sharing her lifelong affection for vegetation with her own children, and how a deeply felt connection with trees informs her work advocating equitable provisions of urban forests and parks.

According to Mayor Wu, forested public spaces are much more than a pleasant amenity or even essential resources for public health and environmental well-being. “Parks uniquely create an opportunity for all of us to be in connection with each other,” she said. In so doing, they foster democratic values at a time when democracy itself is under threat.

“The forest may be the last place where we are truly in community with everyone,” she said.

Mayor Wu was a keynote speaker on the opening evening of “Forest Futures: Will the Forest Save Us All?”, a two-day academic symposium at the GSD organized by Gary Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture, and Anita Berrizbeitia, Professor of Landscape Architecture. The symposium brought together designers, researchers, and expert practitioners from various fields to address “risks and threats, initiatives and improved practices, and speculations on a more secure and more just future for metropolitan and urban forests and the species that inhabit them.” (Video recordings of the full symposium are available online.)

Mayor Wu’s appearance coincided with the opening reception for the related exhibition, Forest Futures, on view in the Druker Design Gallery through March 31. Curated by Berrizbeitia, the exhibition features artworks, design projects, and research that explores how forests have become “designed environments.”

The themes of the conference and exhibition find expression in major policy initiatives, including Boston’s Urban Forest Plan , released in 2022. Created in part to redress the legacies of inequality and environmental injustice, the plan identifies strategies to engage Boston’s different communities to “prioritize, preserve, and grow our tree canopy.”

In January, the mayor signed a public tree protection ordinance, one of the plan’s recommendations. Explaining the importance of these measures after her public remarks, Mayor Wu linked efforts to ensure an equitable distribution of tree canopy to existing urban planning processes. “Every time a new building is built we think about the traffic impacts or the curb cuts,” she said, characterizing the Urban Forest Plan as “a recognition that trees are just as important a part of public infrastructure.” Dense tree canopies confer clear public health benefits, and greenspaces absorb runoff, mitigating floods.

The city’s related Franklin Park Action Plan was initiated to revitalize Boston’s 527-acre Frederick Law Olmsted-designed park, which has fallen into disrepair over the years. A self-described “devotee of Olmsted,” Mayor Wu sees Franklin Park, long overshadowed by the iconic landscape architect’s plan for Central Park in New York, as overdue for recognition as “the culmination of Olmsted’s vision and practices towards the later part of his career.”

Demonstrating deep familiarity with the park, Mayor Wu explained how Olmsted integrated his designs with the natural landscape, his work, “perfectly drawn on the natural features, the drumlins . . . the various boulders and vegetation that were already there.” The process to restore the park has been led by Reed Hilderbrand, the landscape architecture practice of which Gary Hilderbrand is a principal.

Olmsted (1822–1903) was an influential designer whose thoughts about the natural world and public space extended into a democratic vision he called “communitiveness .” As the city aims to restore his design for the park, the focus is on more than “the physical characteristics of how he laid out the park and its unique landscape,” Mayor Wu said. “This was supposed to be a place where people from every background could have respite from the needs and obligations of their day-to-day lives. This could be a place where people from all communities could come together and feel a connection. . . That is Franklin Park’s role in the city of Boston today.”

Mayor Wu shared the stage with keynote speaker William (Ned) Friedman, Director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and Arnold Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. Friedman described his “obsessions” with plants and the need to care for trees on their own terms as an act of recognizing their “standing” in our changing world. Edward Eigen, Senior Lecturer in the History of Landscape and Architecture and MDes Domain Head at the GSD, led a wide-ranging conversation after the talks.

The conversation covered the deep ties between the City of Boston and Arnold Arboretum. In a remarkable arrangement, Harvard gifted the land on which the Arboretum sits to Boston. In turn, the city agreed to lease it back for one thousand years, with the option to renew it for another millennium. (The rental price for 281 acres in the heart of Boston? $1 a year.) Pointing to this “sense of longevity,” the Mayor said, “trees help us understand the passage of time.”

After her public remarks, the mayor said that Arnold Arboretum had recently donated to the city 10 Dawn Redwoods , which will be distributed as part of the Urban Forest Plan in accordance with its community-driven values. The tree is the central image on the Arboretum’s emblem, a testament to the institution’s role in conserving what had been thought an extinct species. Now, the trees will also be a symbol of the Urban Forest Master Plan’s commitment to equity, as the redwoods find homes in Noyes Playground in East Boston, Harambee Park in Dorchester, and at a public housing complex in Mattapan.

Remembering George Baird, 1939–2023

The architect and scholar George Baird served on the faculty at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design as the G. Ware Travelstead Professor of Architecture from 1993–2004. He died on October 17, 2023, at the age of 84.

George Baird invented architectural semiotics in the essay, “’La Dimension Amourese in Architecture,” published in arena in 1967 and reworked in the book Meaning in Architecture, which he edited with Charles Jencks in 1969. George’s preliminary study of the semiotics of architecture elaborates the basic structuralist insight that buildings are not simply physical supports but artifacts and events with meaning, and hence are signs dispersed across some larger social text. That insight is then trained on two of the most enduring of late-modernist myths, the building as a totally designed environment (exemplified by Eero Saarinen’s CBS Building, New York) and the building as a value-free servo-mechanism (exemplified by Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt project, Staffordshire).

The repercussions of George’s critique of modernist dogma would prove enormous, of course, extending over the next decade of architecture theory. But if the linguistic analogy—building as text—was perhaps inevitable (semiotics is designed to explain all cultural phenomena, including architecture) and in certain ways already latent in earlier models of architectural interpretation (those of Emile Kaufmann, John Summerson, or Rudolf Wittkower, for example), one must still decide on the most pertinent and fruitful level of homology between architecture and language. That is, is the individual building like a language, or is architecture as a whole like a language? The first view has affinities with traditional treatments of buildings as organic units whose origins and intentions of formation must be elucidated, whereas the second view, which George adopts, shifts the interpretive vocation considerably. No longer is the interpreter’s task to say what the individual building means (any more than it is the linguist’s task to render the meanings of individual sentences) but rather to show how the conventions of architecture enable buildings to produce meaning. Questions are raised about users’ and readers’ expectations, about how a structure of expectation enters into and directs the design of a building (now thought of as a kind of work of rhetoric), about how any architectural “utterance” is a shared one, shot through with qualities and values, open to dispute, already uttered—questions, in short, about architecture’s public life, to which George would turn to fully in The Space of Appearance in 1995.

In semiotic terms, if architecture as a whole is like a language (langue) then the individual building or project is like a speech act (parole), which entails that the architect cannot simply assign or take away meaning and meaning cannot be axiomatic. Rather architecture becomes a readable text, and the parameters of its legibility are what we mean by rhetoric. Rhetoric operates within the structure of shared expectations and demands an ethical, even erotic relationship with the reader: an “amorous dimension,” a phrase George borrowed from Roland Barthes. But rhetoric is not subjective expression. Its procedures are inseparable from processes of argument and justification with respect to the worldly function of architecture’s making sense.

In all this, George approached his study as a scholar-architect. In this role, he had precedents in Alan Colquoun, Kenneth Frampton, and others, then in London. George and Elizabeth Davis married and moved to London, where George basically began to train himself in semiotics and critical theory. It was in London that George was introduced to Hannah Arendt’s Human Condition, about which he wrote,

While she was not a writer about architecture, over the span of subsequent years, she shaped my thinking about architecture more than any other single figure. I remember distinctly the tingle that ran through my body when I first read her scornful comparison of Jeremy Bentham – the very figure whose corpse I passed by most mornings at University College London – with David Hume, who, she sneered, ‘in contradistinction to Bentham, was still a philosopher.’ Arendt’s discussion of utilitarianism confirmed once and for all in my mind, the pernicious influence of contemporary efforts to revive ‘functionalism’ as a basic premise of compelling architectural theory…. All in all, Arendt, [Ivan] Illich, and [Michel] Foucault together created for me a picture of skepticism of, not to say hostility to, the instrumentalized version of enlightenment rationality, which underpinned my critique of architectural functionalism and has stayed with me to the present day.

As I say, I will always think of George as first and foremost a scholar of architecture. I tried to celebrate this conviction when I was invited to introduce his Preston Thomas lectures at Cornell in 1999. I explained that George’s theory placed Claude Perrault’s concepts of positive and arbitrary beauty into active equivalence with the linguistic distinction between langue and parole, or the generalized grammar (langue) and an individual instance (parole) of speech. For what is achieved should not be understood as a simple simile of architecture as a language but rather as the creation out of two previous codes (beauty and linguistics) an entirely new one, unique to architecture, which is capable of recoding vast quantities of discourse, from eighteenth-century French theory’s concern with the natural basis of architecture, to modernism’s mimetic relationship with industry, to postmodernism’s loosening of the classical order. Rewriting such interactions as components in a complex fraction—positive beauty / arbitrary beauty : langue/parole—enables the enlargement of architectural interpretation to include an Arendt-like social communicative function of architecture’s handling of style, materials, and technology, and to measure the social unconscious of different, competing architectural representations in their specific contexts. Indeed, as George uses it, this feature seems to anticipate postmodernism as a kind of revenge of the parole—of the specific utterance, of personal styles and idiolects. Henceforth, worry about empirical method and total design would be completely eclipsed by concerns with the contexts and instances of meaning.

But during my introduction at Cornell, my bad pronunciation of the French “r” destroyed my attempt to explicate Baird’s Barthes-ian reading of Perrault’s parole! George thanked me for the intro, but left it at that: “Michael, thank you, but I just don’t know what else to say.”

George and I talked much about his theory but surprisingly little about his building, substantial though his professional practice was. Once when Martha and I visited George’s Toronto office on a weekend, George projected what struck me as an odd neutrality toward some of the important projects of the firm. About the wonderful Butterfly Conservatory in Niagara Parks Botanical Garden, a completely unprecedented program in a cold climate, he opined, “We should have thought more about being the bugs. Perhaps we thought too much about the children.” George used the same voice he uses at studio reviews. Engaged but neutral, critical yet open minded, reading the project with an Eames-like “Powers-of-Ten” zoom-out to reframe the butterfly’s narrative and recontextualize the architectural object’s confrontation with the world. Perhaps he was performing for Martha and me; George knew we liked his theatricality. But perhaps, on the other hand, this is what a weekend in the office was for him. He was the office consultant in criticality and social aspiration. He was the in-house philosopher.

George was a well celebrated professional, but his habits are those of a scholar.

Design and Time: An Interview with Offshore

The public program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design features speakers in the design fields and beyond. The series of talks, conferences, and conversations offers an opportunity for the public to join members of the GSD community in cross-disciplinary discussions about the research driving design today.

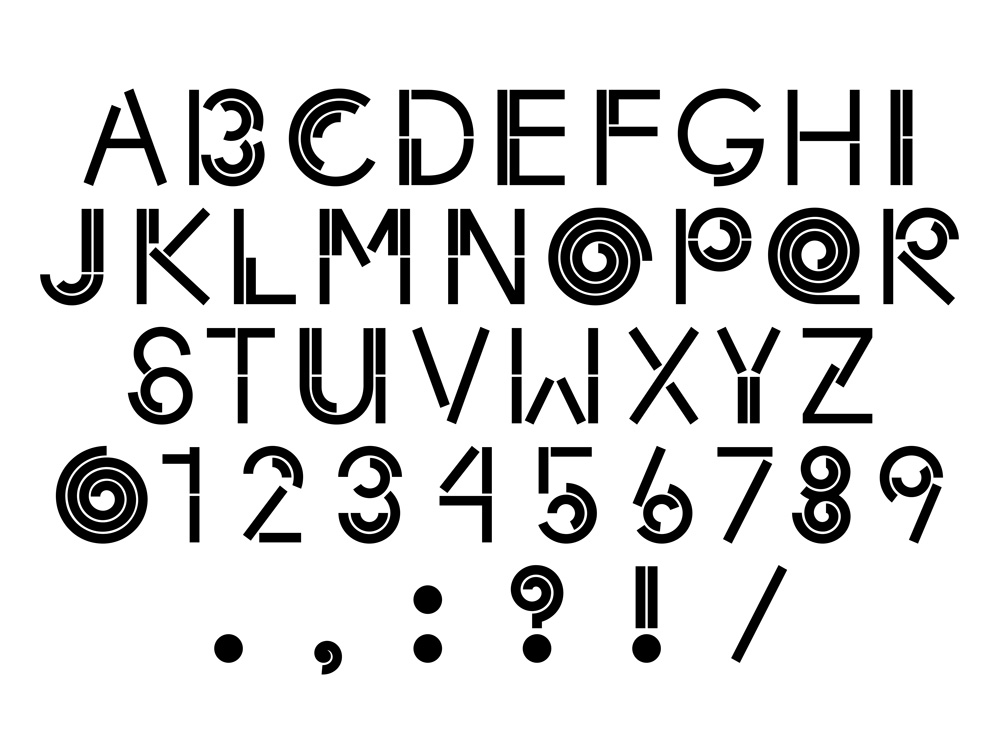

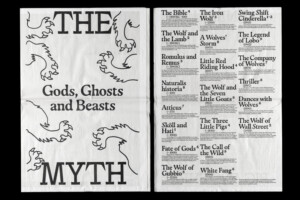

Each year, in an effort to extend an invitation to these programs as widely as possible, the GSD asks graphic designers to create a visual identity that conveys the program’s spirit and mission. For the 2023–2024 academic year, Offshore , the design practice of Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miler, took up that challenge. They created print and digital materials featuring a swirling motif and a spiral-like typeface that distill the energy and intellectual curiosity of the School’s events. To better understand how graphic design relates to the GSD’s public program, Art Director Chad Kloepfer exchanged questions with Miler and Seiffert over email.

Chad Kloepfer: Through innovative printing and custom typography, this year’s poster is a literal whirlwind of color and type. What did you hope to convey through this treatment?

Offshore: A whirlwind of color and type—that is such a nice description. The graphic language for architecture-related projects often features monochrome or more toned-down and serious visual gestures. Additionally, the pandemic years have felt very monotonous in many ways. We wanted to bring some energy and liveliness to this project. It was important for us to convey a vibrant, dynamic, and, to some extent, action-oriented mood.

There is a structured but organic feel to both the typeface and layout, the spiral being a predominant gesture. How did you arrive at this graphic device?

During the design process, we were very focused on striking a balance between sharp, clear, and bold graphical forms while allowing movement and avoiding rigidity. To us, this represents a commitment to precision that does not feel “square,” if that makes sense. The gesture of the spiral comes from the idea that this visual identity lives for one academic year, one cycle, so to say. It can be a very intense and dense period, with a lot of things happening at the same time. We wanted to convey that visually.

I really love the typeface, especially when the circular glyphs are animated. Can you speak a little bit about the development of this typeface?

There are quite a few typefaces out there that feature spirals in their glyphs. But all of those felt either too retro or too organic for this purpose. We were keen to be precise and playful at the same time–to simultaneously create something very constructed and quite dynamic. We made a few hand drawn sketches to find the general proportions and feeling. We also asked our friend Jürg Lehni, who created paper.js and the Scriptographer plugin for Illustrator back in the day, to create a small spiral tool for us. This made it easier and faster to draw very precise spirals with the parameters we needed for the various glyphs. We hope to extend the glyph set with lowercase and more punctuation later this year.

Could walk us through the printing process for the poster?

We used offset printing to produce the poster. This gave us access to radiant spot colors, which was essential for creating the vibrancy we were aiming for. The first step was to print the background layer and the big spiral in black and fluorescent red. The silver layer with all the typographic information cut-out was applied in the second step. This way the typography is displayed by revealing the first printing layer, thereby creating a vivid interaction of the overlapping elements.

Something I really admire in your body of work—and this year’s poster is no exception—is how layered it all feels. I mean this both visually and conceptually. Like a root system, we are taking in what is above ground, but it also hints to non-visible layers that are fun to unpack. Could you discuss the conceptual side of your process? What was the thinking behind this public program identity?

The deeper roots of our approach might be found in our latest fascination for the contemporary discourse around time. Today, many artists and writers are challenging the conventional Western idea that history moves in linear fashion. They are emphasizing the non-linear nature of time instead, thinking of history in loops, dialectics, time bangs, and spirals. For example, Ocean Vuong writes in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: “Some people say history moves in a spiral, not the line we have come to expect. We travel through time in a circular trajectory, our distance increasing from an epicenter only to return again, one circle removed.” We think many of those alternative notions of time are beautiful and fascinating, since they imply a more complex, long-term and intertwined relationship of humans, more-than humans, and the environment. In many ways, these concepts are counter-chronologies, challenging today’s prevalent version of standardized and linear time that serves efficiency, productivity, and a mainly economic perspective on progress and growth. These alternative, nonlinear views on time–some of them in the shape of a spiral–propose a less anthropocentric position, which might help us to synchronize ourselves with a world that is made up of multiple rhythms of being, growth, and decay.

Your portfolio has a striking visual range. Rather than following a set stylistic approach, you seem to generate a vernacular response to the subject matter of each project. What are the underlying continuities within your stylistically diverse body of work?

One underlying continuity within our work is our ongoing interest in multilayered narratives. Stories define who we are, sociologist Arthur W. Franke writes. They do so because they always “work on us, affecting what we are able to see as real, as possible, and as worth doing.” The aesthetics of each project develop from this and similar questions. What style communicates the story we want to tell? What tools do we need to use in order to create the aesthetics we envision? What production processes emphasizes our idea?

In the last five years, we have built manifold narratives, tackling issues ranging from migration, ecology, and interspecies relations to visual histories and design education. Working with various media—publications, websites, drawings, and exhibitions—we are interested in telling stories in an engaging, often multilayered fashion. Unfamiliar maps, vibrant visuals, symbols that expand and challenge the written language, photography, and illustration can coexist in our plots; they create rhythm, intertwine, and unfold unfamiliar perspectives. We tell stories by exploring, questioning, and transgressing the defined spaces of the discipline of Graphic Design while still staying committed to form, aesthetics, and craft.

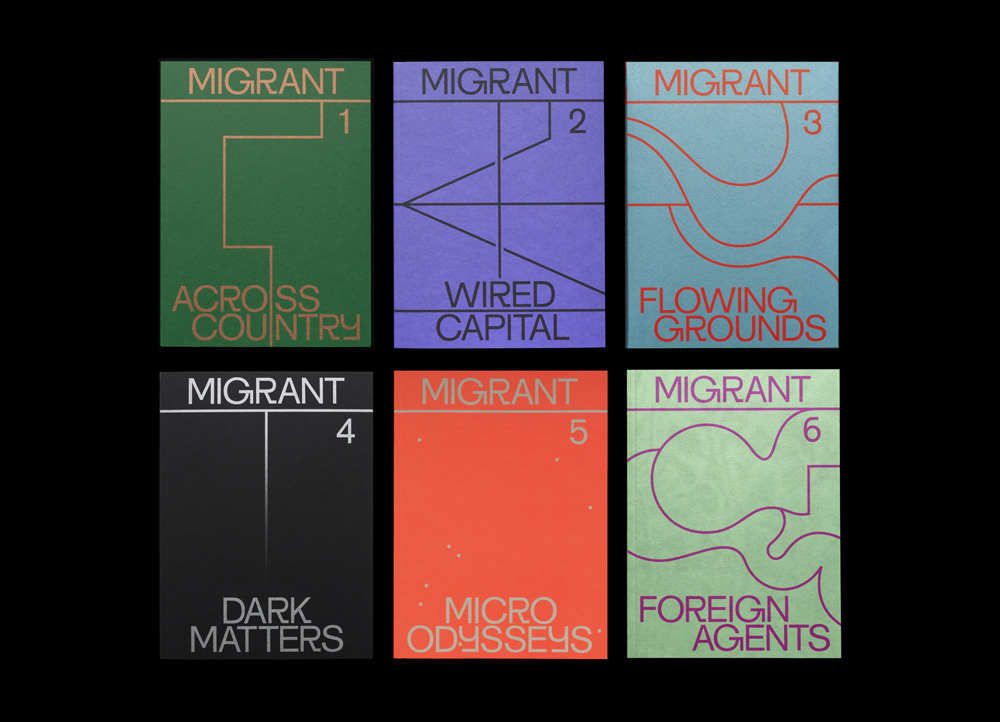

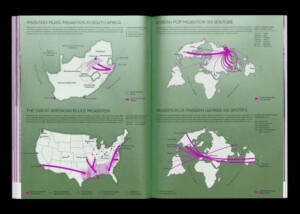

One of the projects that brought your studio to our attention is the publication Migrant Journal , which ran from 2016–2019. You were not just the designers of this publication but also helped found it and were co-editors. Can you speak a little bit about what Migrant Journal was/is and what it meant for your studio?

Migrant Journal was a six-issue publication exploring the circulation of people, goods, information, ideas, plants, and landscapes around the world. Together with our contributors, we looked at the transformative impact this circulation has on contemporary life and spaces around us.

Our endeavor with Migrant Journal has been from the start to look at the world through the lens of these migratory processes—dealing with questions of belonging, national identity, cultural shifts, financial systems, but also landscape transformation, the weather, movement of animals, and global food networks. The idea was born in 2015 when the so-called migrant crisis in the Mediterranean Sea was seemingly the only topic in the news. We felt that there was a huge lack of in-depth information about the complexity of the issue, global interrelations, and the broader concept of migration. In a world of a polarized and populist political climate and increasingly sensationalist media coverage, we felt that it is more important than ever to re-appropriate and destigmatize the term migrant.

In order to break away from the prejudices and clichés of migrants and migration, we asked artists, journalists, academics, designers, architects, philosophers, activists, and citizens to rethink the approach to migration with us and critically explore the new spaces it creates. A printed journal provided a platform for multiple disciplines and voices to talk about an intensely interconnected world that creates a multitude of interdependent forms of migration.

The decision to produce a magazine, and not make a website or a book, was purposeful. We strongly believe that printed publications can create a reading experience that lasts longer than most ephemeral bits of information on the internet. As soon as it’s online, it’s lost in the stream of information, and we didn’t want this. Print is still the technology that ages better than any other carrier of information.

Maps are an integral component of migration. They are all about movement, territory, and space. So it felt very natural to use the technique of mapmaking as a narrative tool for our publication. Maps, as one major component of Migrant Journal, are woven into a diverse set of editorial formats, like essays, images, infographics, reports, and illustrations. Through the materiality of the object we were able to translate complex issues into a format that provides various points of entries in a multilayered manner.

It’s our founding project and has heavily shaped our way of working in many aspects of the practice. At the same time, it defined our studio profile and influences, until today, the projects for which we receive commissions.

Disguised Density: An Excerpt from “The State of Housing Design 2023”

This essay is an excerpt from The State of Housing Design 2023, a book published by the Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) and available to purchase through Harvard University Press. A research center jointly affiliated with the Harvard Kennedy School and the Graduate School of Design, the JCHS has published a widely read annual report, The State of the Nation’s Housing , for over 35 years. The State of Housing Design 2023 provides a design-focused complement to this initiative and was the impetus for a half-day event of talks and panels at the GSD. Edited by Sam Naylor, Daniel D’Oca, and Chris Herbert, The State of Housing Design 2023 is organized around 25 themes that characterize design practice today.

In 2016, architect Barbara Bestor used the term “stealth density ” to describe a multifamily residential development that her firm, Bestor Architecture, designed in Los Angeles’s Echo Park. The neighborhood, historically a mix of Latinx families and bohemian artists and writers, was slowly, then very rapidly, gentrifying in LA’s overheated housing market. Any new construction was bound to be suspect—both as a harbinger of displacement and disruption of the old, streetcar-era urban fabric. Although the term “stealth” conveys a contextually sensitive approach, a way to fit into an existing condition, it also reflects the anxieties of a neighborhood in transition. Changing a neighborhood’s physical character threatens both longtime and recent residents.

Bestor drew inspiration from the modest single-family homes and occasional low-rise courtyard apartment buildings that line Echo Park’s hilly streets. Named Blackbirds, Bestor’s complex combines these two typologies to organize a series of duplexes and triplexes around a central parking court. Each building stealthily resembles a single-family home; the design uses pitched roofs and exterior paint color to break up the bulk of larger volumes, so new construction blends into the surrounding scale. “Two free-standing houses are connected by flashing, and the roofline creates the illusion of one house mass,” Bestor explained to the online publication Dezeen. “Three houses, whose separation is masked, has the illusion of being two houses.”¹

Stealth density is just one possible expression of this strategy. The editors of this book chose “disguised density,” and a 2019 Brookings Institution report used the term “gentle density” to argue that replacing detached single-family houses with more homes on a lot could help reduce housing prices in desirable locations without disrupting the neighborhood. This “missing middle” between the stand-alone home and the dreaded apartment tower takes the form of multifamily townhouses, duplexes, and semi-detached structures packed tightly on a lot. “Building more housing on single-family parcels doesn’t require skyscrapers,” noted the report’s authors, Alex Baca, Patrick McAnaney, and Jenny Schuetz.²

Stealth. Disguised. Gentle. With each, language is used to deflect the fears and misconceptions that have accumu- lated around multifamily housing—biases that align multiunit buildings with the past specters of bleak public housing projects. That new development must slip quietly into a neighborhood underlines the long-held entitlement of home ownership and bias of single-family zoning. The Brookings Institution report, for example, notes that Washington, DC, requires special permission for higher density in areas zoned single-family. Zeroing in on zoning-code terminology, the report identifies how the language of the code privileges low-density to “protect [single-family] areas from invasion by denser types of residential development.” Words like “protect” and “invasion” suggest that code is weaponized against outside threats. Indeed, the report’s authors stress that “‘protection’ entrenches economic and racial segregation.”³ Both Blackbirds and Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects’ (LOHA) multifamily housing development, Canyon Drive, follow City of Los Angeles policy guidelines.

The Small Lot Subdivision Ordinance, first adopted by the city in 2005 and amended in 2016, was touted as a solution to increase affordability in a tight market via infill housing. The ordinance included reduced setback requirements and lot sizes. Building more units—in the form of detached townhouses—on a lot zoned multifamily or commercial was meant to target first-time homebuyers, although it is arguable if this plan was truly successful. In early 2022, two-bedroom, two-bath units at Canyon Drive were sold for around $1.4 million each. Although the price is conceivably less than a ground-up, single-family home on the same lot, the units sold for considerably more than the $1 million average home price in Los Angeles.

The authors of the ordinance recognized that increased density and potentially bulky massing indicative of multifamily housing would set off alarms, so a series of design guidelines dictates specific articulations of facades, entryways, and rooflines to prevent blank and boxy edifices ill-suited to the surrounding context. At Canyon Drive, for example, each unit has a unique identity. LOHA inflected the roofs of the townhouses so that each facade resembles a mid- century-modern A-frame perched atop the garage podium. Similarly, in Greenville, Mississippi, the pitched roofs and shaded front porches that characterize the 42 townhouses of The Reserves at Gray Park suggest that individuation is neither simply an appeasement to NIMBYs nor a market strategy, but also a way of establishing identity and dignity for residents.

Composed of one-, two-, and three-bedroom units, the afford- able housing project by Duvall Decker with the Greater Greenville Housing and Revitalization Association serves low- and very-low-income renters. It’s the city’s largest single-unit housing development in more than 30 years.⁴ Here, disguised density works to deflect the stigma historically associated with affordable housing, while demonstrating that an alternative to a detached single-family home might offer more than the suburban ideal. What if the American Dream was not about individual ownership and a green front lawn but, as illustrated at The Reserves at Gray Park, found in shared public spaces designed to foster community interaction and sustainable site planning?

In many ways, disguised density is a study of aesthetics and perception: both a design exercise in vernacular typologies and a strategic game of hide-and-seek. But camouflage can’t always ward off NIMBY critiques. Opponents of the Ashland Apartments in Santa Monica accused Koning Eizenberg Architecture of “shoe-horning too much building into the site” and brought concerns about increased traffic to Santa Monica’s Architectural Review Board.⁵ The opponents were large neighbors—Santa Monica homeowners concerned about the project’s direct impact on their quality of life and property values. Considered a “preferred project” by the City of Santa Monica, the 10-unit development on a terraced hillside reflects higher density than normally allowed under code but was given an exception to incentivize more family housing to the area. Studios and two- and three-bedroom apartments are divided among four structures. According to the architects, the project achieves a density of 30 units/acre by bridging scales between a residential neighborhood (the source of the complaints) and a high-density, mixed-use development along Lincoln Boulevard to the west.

In 2019, the same year that Ashland Apartments opened, Architecture Australia ran an article about architects Hank Koning and Julie Eizenberg, describing their work as “smart, generous and empathetic,”⁶ which is best embodied at Ashland in the abundance of private and shared outdoor spaces that allow residents room to socialize and take advantage of Southern California indoor-outdoor living.

Ashland Apartments sits on a previously unbuilt lot in the center of the block and is edged on three sides by the backyards of adjacent properties. With no street frontage of its own, the other houses in this highly desirable neighborhood mask its overall density. A long, narrow (and contentious) driveway connects from the curb to the under- ground parking lot. The multiyear clash was, literally, a skirmish over “not in my backyard.”

Although density triggers fears of “too big,” “too much,” or “invasive,” at the heart of these kinds of fights is a battle over the continued viability of single- family zoning in neighborhoods, cities, and states where homelessness is on the rise, affordable housing is out of reach, and sprawl is no longer an option. As a paradigm, single-family zoning was built on pastoral fantasies and systems of social and racial exclusion. Bursting the fever dream of individual homeownership and the loose-fit urbanism it produces is bound to provoke conflict. During an event hosted by Laboratory for Suburbia that questioned what “house” means—both as a spatial product and as home— Gustavo Arellano, an Orange County–based journalist who writes on issues of politics, race, and suburbia, suggested we shatter our collective intoxi- cation, using language that verges on revolution. “[I have to] throw this rock into the windows of the dream I have, and other people have, about where we’re at right now” he said, holding up a painted rock from his childhood.⁷

The sanctity of the American Dream is now undergoing arguably radical, even heretical, change. Across the US, states are rethinking the primacy of single-family zoning, which makes it possible to build multifamily housing in residential neighborhoods—with or without stealth, gentle, or disguised density. Oregon passed legislation eliminating exclusive single-family zoning in 2019. California followed in 2021 with SB 9: The California Home Act, which allows for up to four units on a single-family parcel and promotes infill development.⁸ Its passage was not free from pushback. Under SB 9, landmarked and historic districts are exempt, so the City of Pasadena, a place known for both beautiful craftsman homes and racist histories of redlining, proposed an urgency ordinance declaring the entire city a landmark district, a move that garnered critical media attention and a warning by California Attorney General Rob Bonta.⁹

The Outpost, a four-story, 16-unit project in Portland, Oregon, takes advantage of the state’s higher-density policy and sets a new paradigm for both preservation and how we live together. Beebe Skidmore Architects preserved an existing nineteenth-century home on the property and worked with real estate developer Owen Gabbert and co-living platform Open Door to build a mini-tower: two handsome board-and-batten-clad cubes stacked with a twist.

From the outside, The Outpost’s density doesn’t appear particularly disguised. Its contemporary design displays few tropes of contextual sensitivity, like pitched roofs or vernacular overhangs, even though the other house on the site has both. What is concealed, however, is an experiment in communal living. Shared spaces include the kitchen plus dining and living areas. The project also offers a greater lesson, as disguised density asks us to question the sanctity of the single-family home. As reported by Jay Caspian Kang, suburban neighborhoods are more diverse than our collective imaginary.¹⁰ Existing homes contain multiple generations, older single people, or groups of TikTok influencers. Designing multifamily housing within single-family neighborhoods challenges the notion of the nuclear family as the default resident.

Designing with disguised density strategies allows housing to respond to shifting social and urban planning realities. But is it enough? Well-designed, dense, “missing-middle” housing is necessary to address scarcity and affordability; our language shouldn’t hide the urgency. Disguised density may yield too much agency to NIMBY anxieties and, in doing so, favors modesty over the true need for larger, multiunit buildings.

- “Bestor Architecture Uses ‘Stealth Density’ at Blackbirds Housing in Los Angeles,” https://www .dezeen.com/2016/09/28/bestor-architecture-blackbirds-housing-stealth-density-echo-park-los-angeles/.

- “‘Gentle’ Density Can Save Our Neighborhoods,” https://www.brookings.edu/research/gentle-density-can-save-our-neighborhoods/.

- Ibid.

- “$224K Grant from Planters Bank and Trust and FHLB Dallas Creates 42 Homes,” https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/2018061500 5840/en/224K-Grant-from Planters-Bank-and-Trust-and-FHLB-Dallas-Creates-42-Homes.

- Construction of Santa Monica Apartment Building Appealed,” https://www.surfsantamonica.com/ssm_site/the_lookout /news/News-2015/January -2015/01_23_2015_Construction_of_Santa_Monica _Apartment_%20Building _%20Appealed.html.

- “‘Smart, Generous and Empathetic’: The Housing Projects of Koning Eizenberg Architecture,” https://architectureau.com/articles/hank-koning -and-julie-eizenberg/.

- “Sprawl Session 3: House as Crisis,” https:// laboratoryforsuburbia.site /SS3.

- “Senate Bill 9 Is the Product of a Multi-Year Effort to Develop Solutions to Address California’s Housing Crisis,” https://focus.senate .ca.gov/sb9.

- Attorney General Bonta Puts City of Pasadena on Notice for Violating State Housing Laws,” https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases /attorney-general-bonta-puts-city-pasadena-notice-violating-state-housing-laws.

- “Everything You Think You Know About the Suburbs Is Wrong,” https://www.nytimes.com /2021/11/18/opinion/suburbs-poor-diverse.html.

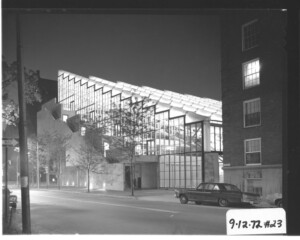

The Plan for a More Sustainable and Accessible Gund Hall

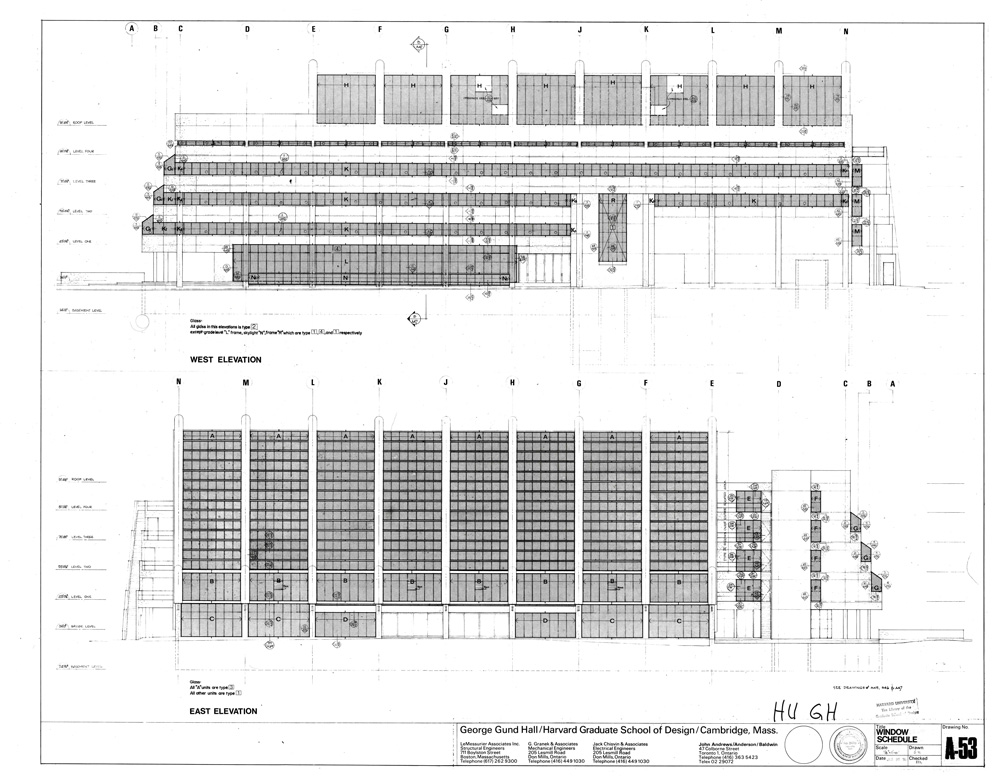

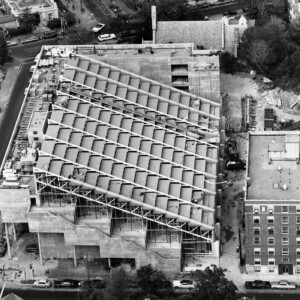

This fall, teams of workers at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design began the first stage in an ambitious renovation of Gund Hall that will be underway through summer 2024. While preserving and updating the School’s iconic main building, the renovations will also vastly increase its energy efficiency. Beyond enhancing the GSD’s core facility, the overall project will model best practices for updating and sustaining mid-twentieth-century buildings.

Designed by John Andrews, Gund Hall first hosted students and faculty in 1972. At the heart of the building are the trays, a five-storey glass-enclosed studio block that serves both as work space and as a center of student community and engagement. In his recent book John Andrews: Architect of Uncommon Sense, Paul Walker writes, “Gund Hall’s famous ‘trays’ came from the priority that Andrews himself gave to the studio as the center of design education.” The trays have retained their vital role at the GSD as one of the most innovative spaces for design pedagogy even as building technology has advanced over the decades. Gund Hall is “largely sheathed in extensive uninsulated glazing systems and minimally insulated exposed architectural concrete,” according to David Fixler, lecturer in architecture at the GSD and an architect specializing in the conservation and rehabilitation of twentieth-century structures. Gund Hall’s existing uninsulated envelope contributes to high energy consumption that translates directly to expensive energy bills, occupant discomfort, and elevated maintenance costs.

Fixler is chair of the Building Committee, which consists of GSD faculty representing the three core disciplines at the school and is charged with overseeing the renovation project.1 “One of the great rehabilitation challenges of our era,” he said, “is to dramatically improve the durability and sustainability of mid-twentieth-century structures while maintaining the architectural essence and character-defining features of these buildings.”

The project’s design is being led by Bruner/Cott Architects, a firm specializing in adaptive transformation and historic preservation. Expert in working with buildings of this period, Bruner/Cott Architects have previously worked with Hopkins Architects and Harvard Real Estate to convert the 1960–1965 Holyoke Center into the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Campus Center. They are part of a large, multi-disciplinary design and construction team that has developed a highly iterative and collaborative process to ensure sound, timely delivery of a state of the art product.2

The renovation process began this fall with a phase to test the design and installation strategies for the upcoming reglazing of the trays. A temporary walled-off “laboratory” has been built in the Pit, a multiuse space in Gund Hall. The mock-ups installed in this laboratory—located on the southeast corner of the building, and including one clerestory section—will be used to assess three replacement glazing systems.

The systems under evaluation include a high-performance double glazing at the east facade slope; a triple glazing at the vertical east facade and clerestories; and a hybrid vacuum-insulated glass (VIG) composite that adds a third layer of insulating glass to the north and south curtain walls. Expectations are especially high for the VIG hybrid, which is not used widely in the United States, but has a strong track record in Europe. By leveraging the insulating properties of the internal vacuum in a glass sandwich that is overall only a few millimeters thicker than conventional double glazing, the hybrid VIG is capable of unprecedented thermal resistance. These hybrid units can deliver energy performance that is two to four times better than standard insulating glass and up to 10 times more efficient than single-pane glass.

Following this testing phase, the project work will begin immediately after commencement in the spring and finish by the fall semester. The trays will be inaccessible during this period.

Replacement of the glazing systems creates an opportunity to make other needed enhancements, including widening the exits onto the outdoor terraces and making them fully accessible. Improvements made to door, sill, hardware, and exterior landing elevations, along with other studio block modifications, will address accessibility issues and bring the building into compliance with current standards where practicable. New under-tray lighting will provide better illumination and upgrade the working environment for these portions of the studio. In addition to the glazing upgrades, a new system of automatic and manual shades for the south and east curtain walls will help mitigate heat gain and control glare.