Julia Thayne on the Challenges of Urban Sustainability

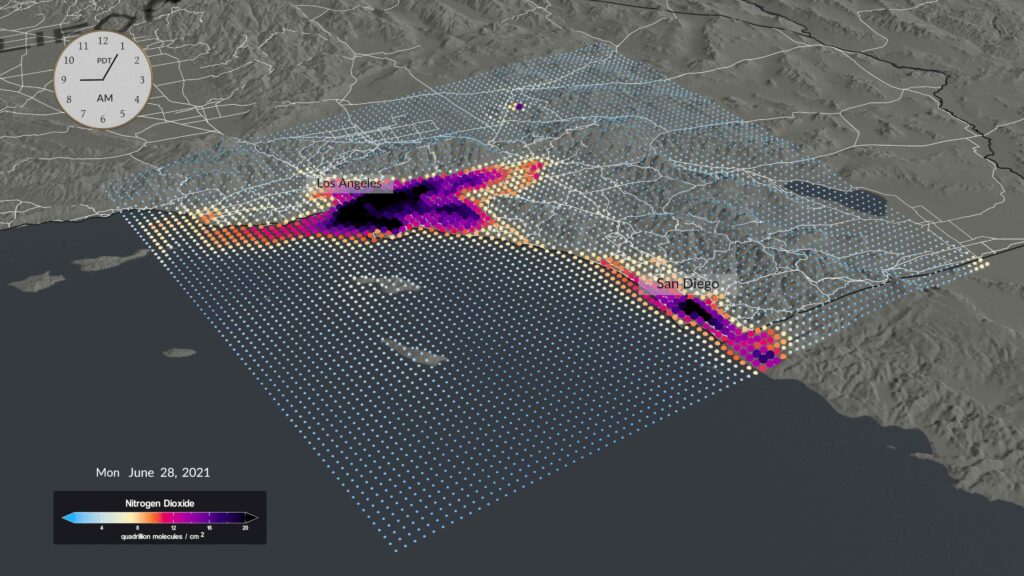

Julia Thayne , Loeb Fellow 2026 and Founding Partner of Twoº & Rising , recently delivered the keynote lecture at the Harvard Business School’s Climate Symposium , where she spoke about cities as catalysts for climate action. Her previous work at climate NGO Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office, and global company Siemens focused on how first-of-a-kind sustainable projects create tipping points for change at scale. Now, as a Loeb Fellow at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), she is applying that experience to research how cities meet their sustainability targets, while adapting to climate change. We met in Gund Hall to talk about her keynote and the work she’s undertaking at the GSD this year, including a new research project on the environmental and social impacts of hyperscale data centers in the U.S.

What is your research here at Harvard, as a Loeb Fellow, focused on?

In general, I’m looking at how cities are meeting their sustainability targets, or not, what that teaches us about where we need to focus moving forward, and how they’re also starting to incorporate more action around adaptation and resilience.

Like many others in climate, though, I’m also taking on a new research project on data centers in the U.S. They already consume a large amount of energy, and are projected to consume even more (in some states as much as 39 percent of total power). They’re polarizing in terms of their impacts. The research I’ve seen so far at Harvard has primarily been about data centers’ power consumption: how do you reduce it, what impacts does it have on investments in the grid, and will the public have to bear the costs of these upgrades. There are some excellent papers out on these topics by experts at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and Harvard Law School, for example.

Along with Robert G. Stone Professor of Sociology Jason Beckfield, and Harvard College undergraduates Brady McNamara, Hailey Akey, and Julie Lopez, and with the support of a Salata Institute Seed Grant, I’ve taken on a research project from a slightly different angle: how do you optimize the environmental and social impacts of future hyperscale data centers in the U.S. that are being built near communities. Our goal is educate people about the impacts, give policy makers and communities ways to shape them, and ultimately affect how these data centers roll out so that they do have benefits.

Fortunately, as I’ve started on this research, I’ve also found the incredible GSD faculty and alumni who’ve been working on this topic for years, like Marina Otero and Tom Oslund. Already, we’ve been discussing how their landscape and architecture designs and practice are shaping what’s being built inside and outside the U.S.

Many of these centers are being constructed right now. How will you intervene in that system?

Remarkably, there are five companies who are primarily responsible for somewhere around one third of new large-scale data center construction. Five. If you can affect the way they think about data center siting, design, community engagements, and impacts, you can affect one third of what’s being built, which translates to hundreds of billions of dollars of investment. That’s pretty wild.

While the deliverables for our research grant are to create primers for key stakeholders, like developers, community groups, and policymakers, to inform actions that could optimize data center development, our ambition is to collaborate with the many others—at Harvard and beyond—who are trying to make sure that the best decisions possible are made around how data centers get built in our country. The development process is remarkably similar company-to-company. A real estate site selection team chooses sites based on power availability and land prices. The engineers help dictate the data center building design based on server needs, power, cooling, and time to construction. Then a team of architects, landscape architects, and engineers collaborate to optimize the design before—or sometimes as—construction is happening.

This is where my experiences in local government, huge tech companies, and research non-profits are coming in handy. I’ve written local policy that helps shape where things get built. I’ve managed tech projects and worked alongside engineers and technologists (usually as the only economist and urban designer in the room). My job at RMI was to think about where the intervention points were for changing systems. For example, how do you pinpoint the change that needs to happen that’ll affect not just one development, but many? So, in a strange way I’ve been preparing for this moment for my whole career, even though I didn’t know it would come.

In some ways, it’s a deeply personal ambition. My family lives in a small city that’s currently grappling with how data center development might affect their local economy and quality of life. In fact, my mom has been a very valuable primary source of information around data center development, sending me local news articles that are guiding some of the ways we’re doing our research! And my niece and nephew, ages 7 and 1, are who I do the work for, always.

Your keynote for the Harvard Business School’s Climate Symposium focused on the work you’ve done across your career on cities?

Exactly. The Harvard Business School (HBS) student groups organizing this year’s Climate Symposium wanted a nontraditional keynote to kick-off the event—somebody with a different perspective than the one they’re normally taught or exposed to at HBS. They gave me a broad topic: “Cities as Catalysts to Climate Action.” I used it as an opportunity to look at why cities are so important to climate action, what they’re doing, and how that has played out (well and poorly) in my own experiences in LA.

Cities are essential to climate action, because they’re the problem—and also hold the keys to the solution. Cities are responsible for roughly 70 percent of the world’s CO2 and methane emissions. They are where people live, work, and spend money. They also bear the brunt of climate change. So, in many ways, cities are both forced and choose to act on mitigation (how you reduce the impacts of human life on climate change) and on adaptation (how you adapt to the ways our climate is changing).

You see that everywhere, from Mexico City, where they’ve greatly expanded their bike and bus rapid transit networks to enhance road safety and give people affordable mobility, to Jakarta, where 40 percent of the city is below sea level and 33 million people are figuring out ways to continue living in the region.

You also see it in LA, where I’ve been living and working for the past 10 years.

What’s happening in LA that makes it different from other cities?

LA was part of the first wave of cities setting ambitious targets around carbon reduction: 50 percent emissions reduction by 2025, zero carbon by 2050. It’s hard to underscore enough that when those targets were set, we had no idea if we could achieve them! I mean, we had plans and models showing how we might achieve them, but as anyone who’s worked in local government knows, plans are very different than reality.

What’s noteworthy is that by 2022, LA had reduced emissions by 20 to 30 percent off the 2025 target, yes, but still—when you think about how hard we make sustainability sound (and how hard it is in practice), it’s pretty impressive. What’s even more impressive is that LA was only 1 percent off the target they set for their own municipal operations. That means what the local government could directly control, they were able to measure and manage. And what’s most impressive is that LA’s economy grew over that time. So, economic growth and environmental harm were essentially de-coupled.

Where was LA not able to meet its targets, and how does that reflect what other cities have done?

Cities generally do five things on climate action. They change where their electricity comes from by incorporating more renewable sources of energy. They reduce the amount of energy they consume, especially in buildings. They shift people and things to more sustainable modes of transportation, like public transit or zero-emissions trucks. They try to reduce waste by not creating it in the first place or re-using it. And, increasingly, they’re adapting to life with different weather conditions.

LA did really well on increasing the amount of renewables in their electricity mix, mainly by investing in big renewable infrastructure projects in and out of the state and changing up how people can buy renewable energy. LA also benefits from (right now) a mild climate where energy efficiency in buildings is easier. The city owns its own port and airports, too, so it was able to control more effectively emissions and pollution from those sources (though they’re definitely still not zero).

They did not do well on people’s mobility, though, or on waste. Some people might chalk that up to bad policy and politics or to something abstract, like “the difficulty of behavioral change,” but I think you have to look deeper. Historical decisions on land use, the lack of readily available and attractive mobility options, inadequate systems and information and accountability about waste, and LA’s importance as both industrial and urban centers – these are critical aspects of LA’s climate story, and they have to be considered when you’re thinking about how to take action on a topic as interdisciplinary and interconnected as climate.

What is your firm, Twoº & Rising, doing to help LA and other cities course correct on climate action?

My business partner and I started Twoº & Rising almost two years ago. We wanted to work with governments, companies, start-ups, investors, and organizations to accelerate the deployment of cleantech solutions in the U.S. “Twoº” is a reference to the Paris Agreement and the goal to keep global warming to 2 degrees by 2030.

Our work in LA specifically has been a lot about mobility, and this idea of giving people mobility options so that they don’t have to rely on cars—and also about adaptation and resilience, a huge and growing topic in the region.

LA is trying to use a series of upcoming global sporting events, like the 2028 Olympic & Paralympic Games, as tipping points for Angelenos to experience getting around the region without their own cars. We’re trying to capitalize on that moment by teaming up with local transportation agencies, as well as foreign start-ups and companies, who can offer high-quality, more affordable, safer ways to experience the city without its legendary traffic.

Similarly, my business partner and I both were temporarily by the LA wildfires in January (him by Eaton, me by Palisades), and are passionate about helping to find solutions to prevent them and to be resilient if and when they do happen. We worked on a project around providing grid resilience during public safety power shut-offs.

What do you hope students here at the GSD would think about in terms of sustainability?

I’ve explicitly devoted my career to climate. At the beginning, I don’t know that’s what I was doing, but now when I sit back, I realize it’s my calling. For some of you, that’ll also be your calling; for others, it’ll be something else. But whether you’re a “housing” person or a “public health” person or a “women’s rights” person or an “economic development” person, I hope you know that you also are, or can also be, a “climate” person. What you’re doing is inextricably linked to the climate and context it’s in, just as what I’m doing on climate is also inextricably linked to housing, public health, social justice, and economic growth or decline. If we can be mindful and intentional about that, we can stop considering these topics as trade-offs and start realizing just how supportive they are of each other.

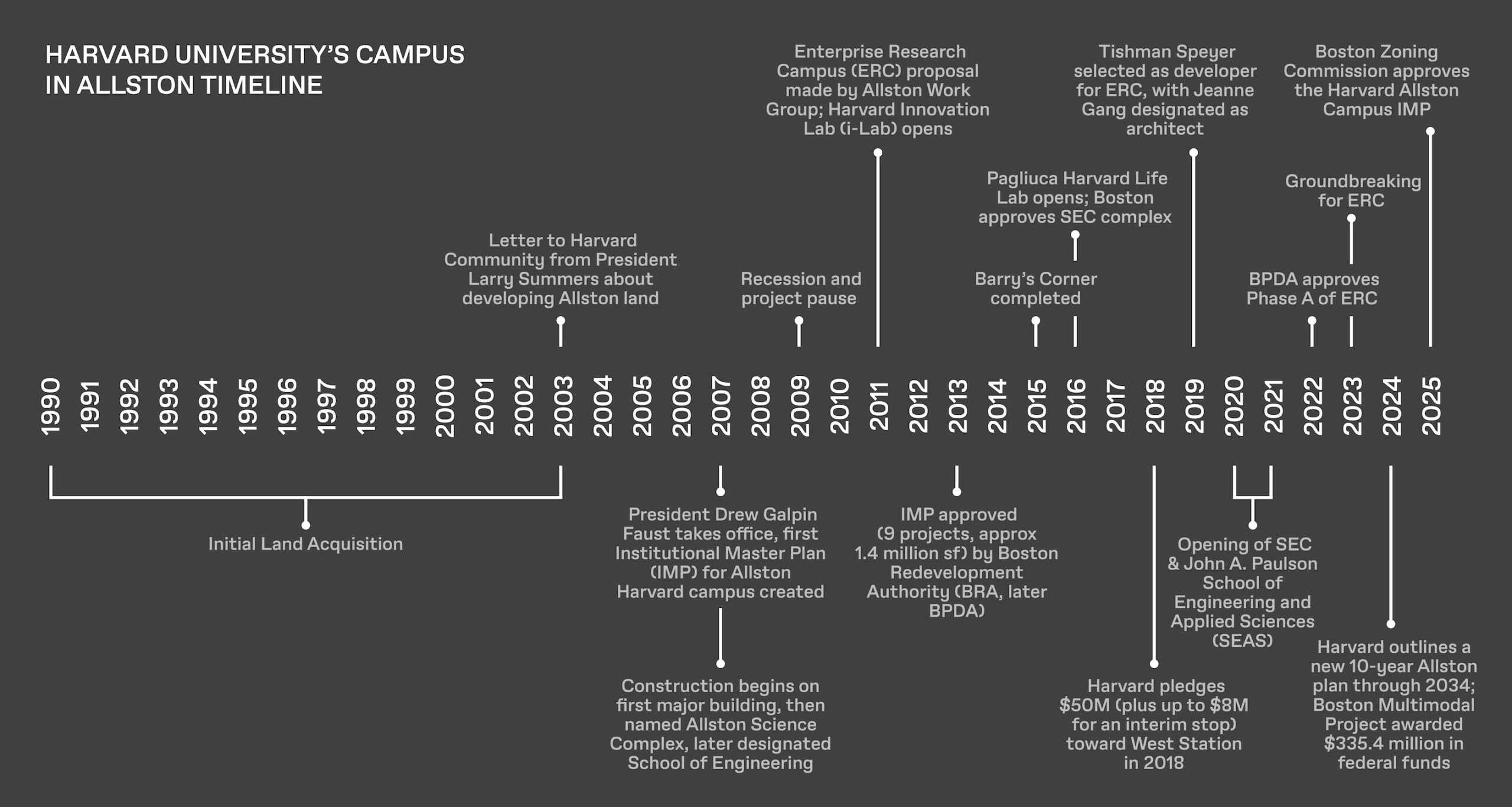

Alex Krieger on the History of Harvard’s Allston Enterprise Research Campus

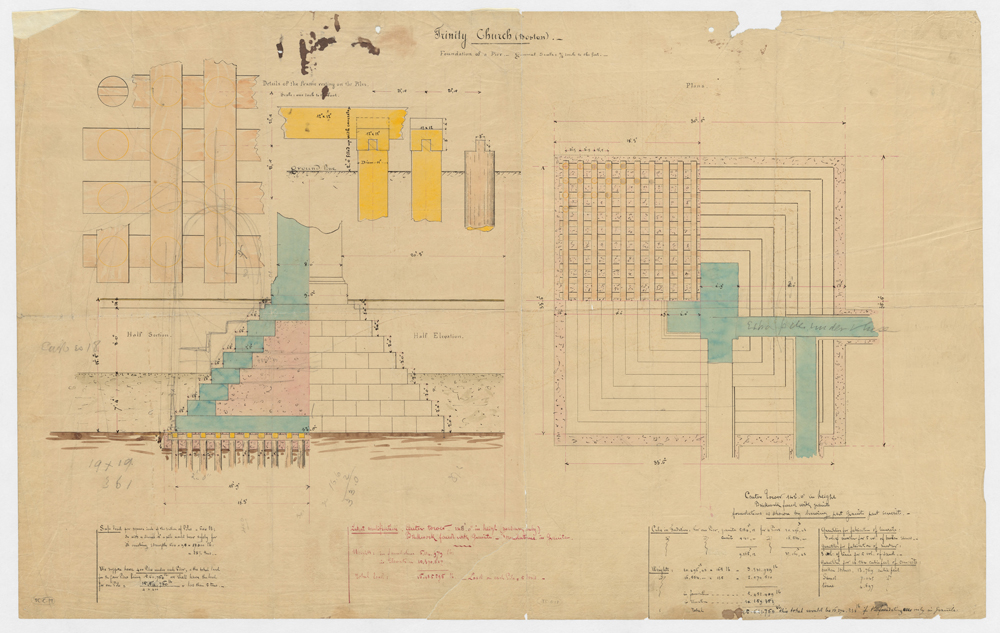

For nearly 50 years, Alex Krieger, professor in practice of urban design, emeritus, taught at the Graduate School of Design (GSD). For about half of those years, he was committed to helping Harvard in the development of the Allston campus , serving on work groups, task forces, and design review committees focused on the project. First working with Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers and his administration in the early 2000s, Krieger helped to initiate a master planning process that, through various iterations over the years, ushered in the Allston campus. The first phase of the Enterprise Research Campus is now nearing completion.

In addition to his scholarship, he’s well-known for his “iconic tour” of Boston that focuses on how the city, which was originally settled on an island, created land to accommodate its growth. He dedicated his career to the study of urbanism, with books including City on a Hill: Urban Idealism in America from the Puritans to the Present (2019), Urban Design (with William Saunders, 2009), and Mapping Boston (with David Cobb and Amy Turner, 1999).

Here, he recounts the history of the Allston campus and how he’s witnessed—and helped shape—its evolution into the landscape we see today, with the opening of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center , the “front door to the Enterprise Research Campus.”

How did the idea for a campus expansion originate?

Upon assuming the presidency, and with the then-recent public acknowledgment by the university that it had been acquiring land in Allston, Larry Summers announced the need for an ambitious master plan to prepare Harvard for its next decades of growth. He would reveal his own ambition that Allston would enable Harvard to establish “the Silicon Valley of the East,” given the university’s leadership in the sciences, and its researchers’ role in the mapping of the human genome that had just been completed by the International Human Genome Project. At the president’s direction, an international search for architects and planners ensued.

My first significant role was advising on the start of the overall planning process and becoming a member of the architect/planner selection committee for the master plan. I worked with Harvard Vice President for Administration Sally Zeckhauser, who directed the search process. We visited firms around the world, and in 2005, selected Cooper Robertson, Frank Gehry, and the Olin Partnership. At Sally Zeckhauser’s request, I began to serve on the design advisory committee as the master plan commenced and proceeded.

Concurrently, I was asked to develop initial programming guidelines for the future campus, which, late in 2005 was released as Programming for the Public Realm of the Harvard Allston Campus. The Cooper Robertson plan was made public in 2007. It gained much attention and publicity, even as we all knew that it would evolve significantly over the years. Several subsequent planning efforts with other planners followed.

When did construction in Allston begin?

The next significant event, in my memory, was the commissioning of the firm Behnisch Architeken, from Germany, to design what, in nine long years, would become the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. However, it was initially planned to be a research and teaching facility for continuing stem cell, genome and life/health sciences innovation. Again, I served on the architect selection committee and on the design review committee that followed.

The “Great Recession” of 2008-10 led to a substantial decline in Harvard’s endowment, and construction had slowed during 2009 and halted in 2010. Three underground levels had been built, intended for a large garage and a district energy facility. The District Energy Facility (DEF), was later built separately, designed by Andrea Leers of Leers Weinzapfel Associates, a frequent visiting faculty at the GSD. For much of the next five years, only the roof of those underground levels was visible, with four humongous construction cranes left idle and visible from afar. This was great fodder for The Boston Globe.

I remember; it was infamous. How long did it take for construction to get back on track?

Drew Galpin Faust became Harvard’s President in 2007. Because of the national economic downturn, she became less concerned with expanding Harvard and focused on projects such as the adaptation of Holyoke Center to a student union. In Allston, President Faust focused on the reuse of some of the properties left vacant by Harvard’s earlier acquisitions, helping to attract new tenants to provide neighborhood services and amenities.

Katie Lapp who became the Executive Vice President for Administration shortly following Zekhouser’s retirement in 2009, began to encourage President Faust to restart planning for Allston. I was part of various informal conversations about what to do with the unfinished project. A science facility had in the interim been built in Cambridge and so different uses needed to be identified before construction could resume.

There were various ideas. One thought was that one of the Longwood Medical Area (LMA) hospitals, or the School of Public Health might relocate to sit on top of the “shortest building,” since there was little space for additional growth at the LMA. Some might find that idea unlikely, but, at the time Chan Krieger & Associates was planning in the LMA, and I heard such conversations there, not just in Cambridge. Ultimately, of course, the Science and Engineering Complex (SEC)

, home of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), was the result.

There was also some discussion about a long-term future for Harvard’s acquisition of the Beacon Rail Yards and adjacent land under the Mass Pike, slated for eventual reconstruction. President Faust and Harvard leadership were becoming aware of just how much land was under Harvard’s control and cognizant that not all of it would be needed for Harvard’s academics.

How did the university decide they’d manage that land, and shift towards a new vision for the ERC?

These informal conversations and brainstorming sessions culminated in the formation of a new Allston planning committee, the Allston Work Team in 2010. I became one of the three co-chairs of that committee, along with Bill Purcell, former Mayor of Nashville, then at the Kennedy School, and Harvard Business School Professor Peter Tufano. The Work Team included the participation of most of Harvard’s Deans, Drew Faust herself, invited urban development experts, and of course, Katie Lapp.

Notions about a new kind of research campus, perhaps to compete with booming Kendall Square (which was beginning to be referred to as “the smartest square mile on the planet”) were already in the air. In Boston, Mayor Menino began to develop the concept of the Seaport Innovation Center. Underway were early phases of what, a decade later, would become the Cambridge Crossing innovation district, under the leadership of former Harvard planner Mark Johnson (MLAUD ’82). Harvard realized they’d better get into this game.

How did they balance community and university needs in the final design?

The Allston Work Team commenced serious discussion about what an Enterprise Research Campus (ERC) might become; supported the resumption of construction for what would become the Engineering School; initiated plans for graduate student and faculty housing, which led in 2015 to the Continuum Residences in Barry’s Corner, with Trader Joe’s at the base; explored how a needed hotel and conference center might become part of early phases; and continued exploring how to revive retail and community facilities around Barry’s Corner and along Western Avenue.

What can you tell us about the selection of Tishman Speyer

as the developer, and Jeanne Gang as the architect of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center

?

In 2018, Tom Glynn became the founding CEO of the Harvard Alston Land Company, and I helped Tom get up to speed on prior Allston planning efforts. We knew each other, as Chan Krieger had served Massport and earlier Partners Healthcare, both institutions he had led. We also had informal conversations about the Boston area development community, as, under his leadership, Harvard was getting closer and closer to proceeding with the selection of a development team for the ERC. I was not involved in that selection process but was quite pleased when Tishman Speyer announced that Jeanne Gang would play a major design role, including, of course, in the design of the Treehouse conference facility.

So, the Allston Work Team helped shape today’s Allston campus, with the November 2025 opening of the David Rubenstein Treehouse conference center, and the ERC now well underway

?

Yes, right now, Phase One is nearing completion, which encompasses nine acres. This first mixed-use cluster includes space for research, housing, a hotel, and the conference center. It will form “the prow” or “beacon” for future phases of the ERC, as the economy allows.

In 2010, the ERC

was just emerging as an idea, and seemed like a way to complement the future Science and Engineering Complex (SEC)

, once construction resumed. Behnisch Architekten

, the architect for the initial construction, had made the brilliant decision to maintain construction liability during those years. Without a building mass on top there was the possibility that those three unfinished levels would begin rising out of the ground due to groundwater hydrostatic pressure. So, it made sense to bring Behnisch Architekten back, though some at Harvard felt that the design was too modern and unlike Harvard. The building has acquired iconic status, and as Stefan Behnisch promised, is one of the world’s most energy efficient science facilities.

I remained on the design review committee for the project, alongside former GSD Dean Mohsen Mostavi, and later Jeanne Gang, as well.

How would you characterize Harvard’s relationship with the Allston community?

The relationship

has improved over time, beginning rather badlywhen it was first revealed that Harvard had secretly bought 52.6 acres of Allston land in the late 1980s and 1990s

. Harvard has since substantially invested in Allston especially along the Western Avenue corridor. As I mentioned, President Faust and Katie Lapp began to focus more attention on neighborhood concerns and needs, and this has continued under Presidents Bacow and Garber.

Of course, expressions of impatience on the part of the Allston community remain, citizens always asking Harvard to reveal any additional plans, plus deliver on some now-old promises. For example, mention the Greenway, and residents will say, ‘Those Harvard people, they promised that to us two decades ago.’ Indeed, a greenway was identified in the initial Cooper Robertson master plan, a continuous pedestrian park-like corridor from the Allston Public Library to the Charles River. Parts of it have been realized, but one long segment remains missing.

The ERC is adding a segment at its center; it is beautifully designed. The trouble is, this segment is separated from the portions of the Greenway that exist, by those not yet built. As the ERC fills with users and tenants, it may make this space seem like it’s proprietary to the ERC. Allston folks may not understand that it’s part of the long-promised Greenway, until Harvard builds the rest of it. I’ve been very vocal about this issue, to the point where everyone was sick of hearing it. Harvard will soon, I hope, complete the missing segments and it will all turn out okay.

Harvard deserves more credit than it sometimes gets from Allston neighbors. As far as I know, Harvard has committed something like $50 million at least three times—once for the Beacon Yards transit station

. The current ten-year Allston plan promises an additional $53 million in community benefits. Another large sum is slated towards the reconstruction of the Turnpike. Finally, less publicly so far, another $50 million-or-so has been quietly promised for the eventual realignment of a portion of Storrow Drive to enable the widening of the Esplanade along the Charles River.

How do you feel about handing off the Allston project, now that you’ve stepped back from the planning process?

Well, I still get to offer opinions, such as pressing the Business School to do something with its huge parking lot right across the street from the ERC, and cajoling Harvard to complete the Greenway. My last role was to serve on the design review committee for the A.R.T. project. This will be a truly wonderful addition to North Harvard Street and Barry’s Corner. The Allston Campus and the revitalization of the Allston neighborhood are progressing well.

Malkit Shoshan on Design as an Agent of Change

Class Day at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) is a celebratory time for graduating students and their families, a day to honor achievements and reflect on the potential of a design education to impact the world beyond Harvard. In past years, invited speakers from outside the GSD community have joined the proceedings to share perspectives on design shaped through their own professional, academic, and philanthropic pursuits. The Class of 2025 will hear from someone who is already well-known at Gund Hall, and whose work is at the forefront of what design means for the world today—a world in conflict.

Malkit Shoshan, a design critic in Urban Planning and Design at the GSD, has built a practice and pedagogical methodology that foregrounds how designers can understand the sources of conflict and ultimately envision a more just and peaceful world. Much of her early work originated in the specific histories and geographies of Israel and Palestine. As founder and director of the architectural think tank Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST) , Shoshan explores spaces of conflict in the region, foregrounds their histories, and envisions possible futures.

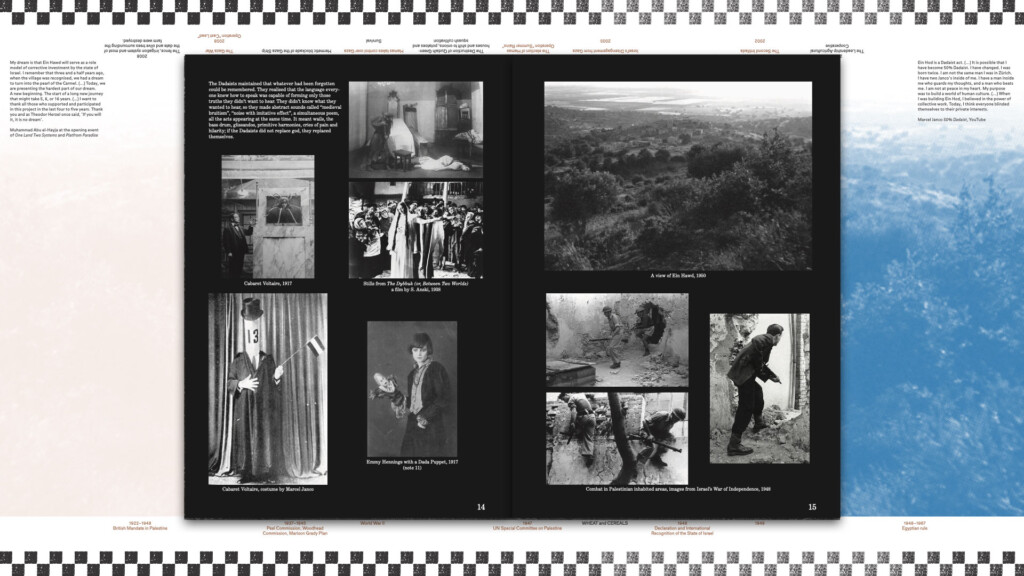

Over the past year, Shoshan has shared her perspective with the GSD in the role of Senior Loeb Scholar, another position that, in the past, has been filled by visiting scholars and practitioners. In this vital role Shoshan, presented her work and led a series of conversations that brought together interdisciplinary participants. She challenged the community to think deeply about how design can both address conflict in the present and define spaces of care and repair. Shoshan’s visually rich presentations featured layered images that evoke the complexity of her subject. Archival materials, detailed geographic studies, and personal stories came together to drive new narratives.

An ethos of design informed by a commitment to human rights underlies Shoshan’s courses at the GSD, including Forms of Assembly, an advanced research seminar for Master in Design Studies (MDes) students to prepare open projects. The course encourages approaches to design that inspire democratic processes and broad participatory discussions. It is in that spirit that Shoshan will address her students and the wider community. In advance of her address, Shoshan spoke with the GSD’s William Smith about her work and her message to the Class of 2025.

Given the many projects that you currently have underway as a teacher, scholar, and practitioner, why was it important to you to take on the additional role of Senior Loeb Scholar?

My work is situated at the intersection of spatial design and human rights. We at FAST use architecture, urban planning, and participatory design processes to make visible and address public concerns, co-developing alternative visions through design. We primarily collaborate with institutions such as UN agencies but also work directly with local communities in conflict-affected regions. Our initial projects, which started decades ago, were in Israel-Palestine, my homeland.

The Senior Loeb Scholarship, I believe, was a response to the events following October 7th. The brutal Hamas attack on Israeli civilians was devastating, as was the subsequent Israeli response. We are part of an international community, interconnected by shared humanity. Moreover, the technologies available us today project the news in eerie high resolution and in real-time, straight into our mobile devices. Even at a distance, we are close to each other.

This period was overwhelming and deeply personal. It was especially painful for me: most of my family is in Israel, and I have friends in Gaza. I have been working on a project since 2020 with a group of Gazan farmers, studying how the Israeli blockade and occupation protocols impact daily life on their small farm. This project was awarded the Silver Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Sadly, the farm has now been destroyed; many farmers have been killed, and those who remain are living in tents, surviving each day, hour by hour, minute by minute.

All of this is part of my personal background, but I was not alone in feeling overwhelmed. At the GSD, I had students eager to talk about these issues. They wanted a safe space for conversations—personal and professional. Because we are all driven by hope, I used the Senior Loeb Scholarship as an umbrella to organize a series of lectures, events, conversations, and workshops with students and practitioners—including scholars, policymakers, civil servants, artists, architects, and human rights lawyers. The goal was to explore how injustice manifests at different scales and in various spaces and to learn how spatial design can contribute to addressing these complex issues.

One of the discussions you organized focused on the theme of “care.” How does care manifest in design?

An important aspect for me was emphasizing not only the humanization of each other but also care amidst the violence that surrounds us. We cannot ignore or suppress these narratives. In her book The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit writes:

“What’s your story? It’s all in the telling. Stories are compasses and architecture; we navigate by them, we build our sanctuaries and prisons out of them. To be without a story is to be lost in a vast world that spreads in all directions like arctic tundra or sea ice. To love someone is to put yourself in their place, which is to put yourself in their story, or figure out how to tell yourself their story.”

I often cite this quote, as well as the long and important essay of Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others. Sontag discusses the role of empathy and imagination, with a virtual meditative conversation with Virginia Woolf—highlighting the challenge we face in truly understanding and imagining others’ experiences and suffering. These writings inspired the framework for my events: how can we, during the most difficult times, put ourselves in someone else’s story? How can design help foster empathy and expand our imagination?

Design represents a way to imagine what else is possible, to speculate on a future beyond violence and despair. It provides a space where we can rethink and reimagine our possibilities, offering hope in a very challenging world. Escaping this sense of helplessness is difficult, but I believe that engaging with design as a form of active hope can be part of the solution.

By sharing your work and leading discussions informed by decades of practice, you gave the GSD community and important perspective. What did you learn through the conversations you inspired as Senior Loeb Scholar?

The role was an opportunity to create a space for meaningful dialogue around complex, often contested issues. These conversations are inherently challenging because they touch on deeply held beliefs, systemic inequalities, and emotional investments. The nature of these discussions underscores the difficulty in addressing contentious topics; many individuals tend to be entrenched in their opinions or operate within echo chambers, facilitated by social media and technological platforms that often reinforce rather than challenge individual perspectives.

Through guiding these discussions, I learned that while the space for dialogue can be fraught with discomfort, it is also profoundly necessary. It’s a space where confusion and vulnerability are not only inevitable but also valuable. Encountering students and community members who are initially shy or unsure about forming opinions reminded me that many people need time, patience, and a safe environment to engage meaningfully with complex issues. It became clear that the process of questioning, openness, and active listening are essential components of growth—not just for individuals but for the collective community. It is not about having answers, but about listening, and that is something that I also had to work and need to keep working on myself; it is so much easier to speak than to listen and just realize that there are always so many narratives at place, and that’s OK.

My main goal with these events was to hold space—creating an environment where difficult conversations can take place ideally without judgment. This meant acknowledging the emotional labor involved and recognizing that meaningful engagement requires time and care. The Senior Loeb Scholars program provided a valuable umbrella for these efforts, demonstrating that institutional commitment to such dialogue can build trust and slowly encourage a deeper understanding of the situations and of ourselves.

Importantly, I feel that we need to find ways to embed these kinds of spaces in a more systemic way to allow sustaining these formal and informal critical conversations beyond isolated events. Designing intentional structures which is also not overly institutional and prescribed in advance within academic and professional communities can enable ongoing engagement with uncomfortable knowledge.

How do you, as a designer, work with archival materials and historical sources to understand today’s conflicts?

The archive emerges as an essential, yet complex, tool for understanding and intervening in contested spaces. It isn’t merely a collection of past documents; it functions as a living infrastructure for knowledge production, memory, and power. Navigating the archive requires care, criticality, and awareness of its inherent contours—since archives are often political spaces that both preserve contestation and serve as sites of potential intervention.

The landscape on which we design is fundamentally non-neutral. It is a terrain layered with histories, claims of ownership, power dynamics, and social conflicts. The lines we inscribe on this terrain—whether literal boundaries or symbolic demarcations—are rendered visible through archival materials such as maps, photographs, governmental records, or historical narratives. These lines both reflect and shape ongoing territorial disputes and social struggles, serving as contested evidence of ownership and control.

In this context, the act of working with archives becomes an act of engagement with these underlying conflicts. As Saidiya Hartman has extensively discussed, archives hold evidence not only of victory but also of subjugation, erasure, and exclusion. Recognizing this, I approach archives with an ethical awareness: they reflect histories of dominance and resistance, of displacement and resilience. To neglect this complexity is to risk reproducing or silencing parts of these histories.

My own engagement with archives has been shaped by historical materials from my country, Israel. For example, I have studied the archives of the architecture faculty at the Technion, where old national atlases from the post-World War II era (which were not exclusive to Israel), exemplified rapid processes of nation building. In my case, I wanted to understand the history of my country, so I studied these atlases and the associated material (such as regional masterplans) which documented not only physical rebuilding but also the reconstruction of national identity through master plans and territorial delineations. Maps, in this context, are more than representations—they are sites where the national project unfolds at an unprecedented pace, often implicating complex processes of displacement, exclusion, and territorial assertion.

In my teaching and practice, I emphasize that designing in such environments demands sensitivity to these histories. It requires recognizing that spaces carry stories of belonging, displacement, and resilience. Our interventions must be aware of their capacity to reinforce existing structures or open pathways toward repair and inclusion.

Beyond academia, I direct a foundation based in Amsterdam dedicated to engaging with archives as infrastructures for knowledge and intervention. Each project we undertake integrates archival research—collecting stories of often-invisible realities, histories, and cultural practices. For example, our research on the impact of UN peacekeeping missions is stored in the national architecture archive of the Netherlands, serving both as documentation and as a resource for future inquiry. Similarly, our studies of Gaza’s farming communities are preserved within a textile museum archive, reinforcing the importance of diverse, community-driven histories.

Archives can reveal stories that challenge existing narratives, highlight marginalized voices, and offer pathways toward understanding and reconciliation. They remind us that spaces are not merely physical entities but are constructed through histories, memories, and social struggles. As designers, our role is to navigate these complexities ethically, critically, and creatively—using historical sources not as definitive answers but as avenues for engaging deeply with the present and envisioning more just futures.

Many of the MDes open projects presented in your Spring 2025 course “Forms of Assembly: All Things Considered” grappled with difficult challenges related to environmental degradation or longstanding conflicts. But there was also an overarching belief in the power of public assembly and collective expression. How do you encourage students to maintain that sense of hope and purpose as designers amid seemingly overwhelming challenges?

I don’t need to encourage the students. They are extremely motivated and concerned, and they are eager to discover what tools they have and what they can do with design to contribute to society and their communities.

I started offering this course during the Covid-19 pandemic, when all of us were confined to our homes, often living in different countries, cultures, and time zones. The GSD’s international makeup is one of its strengths; we are exposed to so many cultures and languages. As we met via Zoom at the time, the question of assembly became very relevant. How do we assemble under these conditions? We explored spaces of dialogue, exchange of ideas, and solidarity; spaces which perhaps resemble the description of the world by Hannah Arendt—the invisible table that we humans gather around to exchange our ideas and make them public.

Students began sending postcards and items they cared about across the globe to connect more intimately with each other. They developed lasting friendships and eventually made parts of these stories public. A student shared a key to her art studio in Shanghai with a student from Brooklyn while exploring how to share both her process and her exhibition with the group. They exchanged recipes and hosted online dinner parties, which I liked because it allowed us to share more of our personal backgrounds than when we meet in person.

In that first class, two students—one from Bangalore, India, and another from Santa Fe, New Mexico—looked into the archives of the Peabody Museum and created a two-day international symposium online. Both students come from communities that have been oppressed under imperialism—India and the Navaho Nation—so each looked into different entries and provenance items shown at the museum. The symposium they initiated was beautiful, bringing together so many diverse voices.

How has the class evolved since the pandemic?

In a peculiar way, given recent news regarding the risks of academic freedom and the international make up of our school, this question has received a new sense of relevance. How to assemble? What are the forms of effective assemblies we can enact under stress?

We can only face the challenges of today as a collective, an assembly, as practitioners, as human beings, which are part of a bigger web of actors. The stresses we are under, whether the climate crisis, diminishing democracies, polarization, growing inequality, or the fact that even mentioning the word “justice” as a value and direction we should all aspire toward has become contested, we can, of course, address these issues—and need to address these issues—at a personal level. But these are collective, societal challenges, and to contribute to change, the assembly is important.

Yet this assembly should not be considered a homogeneous group. Forms of Assembly: All Things Considered, the course from Spring 2025, is about the power and beauty of diverse voices and opinions, of the different forms of life that inhabit this planet and the importance of situated knowledges –the depth of knowledge that exist in each site we engage with. In We Have Never Been Modern, Bruno Latour suggests that we should begin thinking about a new constitution that is more inclusive, representing not only humans but also nonhuman objects and things: all those who inhabit this planet.

Many of the projects in this class originated from a very personal place and turned it into something much bigger. Students are often much more passionate and can understand how to navigate such complexity better when working on issues they care about. They can learn how to engage design and apply it to their cause because of their familiarity with the context. After that, the methods they develop can be used in other cases and places.

This year, for instance, one student spoke about order and freedom in contested times. Building on her Jewish heritage and family ritual of the Passover Eve Seder and its tale of physical and spiritual transformation from slavery to freedom, she saw an opportunity to speak about what liberation means for everyone else. Another student investigated, for the first time, the impact of a dam on her community in India and the protracted environmental degradation it caused. She looked at it from multidisciplinary perspectives, from labor conditions to agricultural practices to gender and class disparities.

Another student worked with a women’s NGO from Mexico that is working continuously to address cartel violence, trace the hundreds of thousands of missing people (some of whom are their family members—sons, husbands, brothers, fathers), and campaign for policy change. The student from Mexico worked with them to create a nomadic exhibition that helps raise awareness, creating a space of gathering/assemblies in different spaces that function not only as a representation tool but also as a dynamic archive, a memorial, and a space that brings victims together. It was a beautiful project that also creates a direct bridge from the academia to the real world.

How you see the role of the designer in today’s world of multiple, overlapping crisis, from climate change to military conflict to the rise of authoritarianism?

In our increasingly complex, siloed, and fragmented world—what many now refer to as a “polycrisis”—the role of the designer is more vital than ever. Design can serve as a bridge—connecting ideas, sectors, communities, and ecological systems that are often seen as isolated or incompatible. In a world rife with fragmentation, design can demonstrate the relationality between elements, highlighting our blind spots while expanding our collective imagination of what is possible. It becomes a lens for understanding and intervening in the interconnected webs that shape societal and environmental outcomes.

Our world is composed of complex ecosystems—built environments, social networks, natural landscapes—that are shaped by socio-economic, cultural, historical, and financial factors. These factors influence the quality of our lives and are often invisible or overlooked in traditional approaches. When we use design to examine these interconnections, it opens entirely new possibilities for insight: understanding how policies influence environments, how technology shapes urban life, or how financial mechanisms impact ecological stability. Design is thus a tool for generating knowledge in the in-between spaces—those zones where disciplines, ideas, and stakeholders converge.

This approach transforms design from a static object into an active agent—one that can reveal past and present damages, stimulate dialogue, and propose alternative futures. For example, in the classroom we often addressing migration and environmental challenges. Students explore the complexities of migration—designing support systems, informational tools, and policy proposals that for instance facilitate safer journeys for migrants from Latin America to the United States. These projects involve engagement with NGOs, legal experts, and local communities, demonstrating how design can serve as a strategic instrument—amplifying voices and fostering tangible change

Design has the power to act as a catalyst for systemic change. I encounter this both through my practice and the ongoing collaborations, as the director of FAST with UN agencies—one of which influenced a UN resolution on peacekeeping missions in 2017, as well as important policy papers—and through my pedagogy, the work we do in class, where students are developing innovative proposals. The design of the built environment and design thinking are uniquely suited to help us navigate complexity because of their multi-scalar, multi-temporal, and interdisciplinary nature.

This semester, in another course I taught—Spatial Design Strategies for Climate and Conflict-Induced Migration—we worked closely with UNHCR and UN Habitat to gain a deeper understanding of the spatial challenges faced by a world in motion. With hundreds of millions of displaced persons, the question of how we design homes for people on the move has received new salience.

What would you say to those who might downplay the importance of design in the face of seemingly more urgent or pressing issues?

In a world of urgent crises, dismissing design as irrelevant or secondary is a mistake. Instead, we must recognize that design is a potent agent—one that can connect fragmented systems, empower communities, and foster innovative pathways toward a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable future.

Dong-Ping Wong in Conversation with Emily Hsee, on the Chinese Merchants Building

Pairs is a student-run journal at the GSD, which centers conversations between GSD students and guests, about an archive at Harvard or beyond. In this excerpt from Pairs 05, editor Emily Hsee speaks with architect Dong-Ping Wong about the history of the Chinese Merchants Association Building in Boston, which was designed by Edwin Chin-Park and completed in 1949. The building was funded by local neighborhood associations and represented Chinatown’s economic and social progress since World War II. It was partially demolished in 1954 during construction of the Fitzgerald Expressway. Hsee and Wong address the history of the building, the culture of Chinatown in Boston and New York, and recent shifts in the perception of Chinese American culture in the United States.

Dong-Ping Wong is the founding director of Food New York , a design firm specializing in transforming environments, from structures to landscapes. Current and past projects have included a Cayman Islands garden and +POOL, the world’s first floating water-filtering pool . Previously, he co-founded Family New York, designing for Off-White, Kanye West, and contemporary art museums.

Emily Hsee is a 2024 graduate of the GSD Master of Architecture I program. She is originally from Chicago and has worked between New York City and Shanghai. Her research and interests focus on multi-family affordable housing design solutions.

Emily Hsee

Historically, Chinatowns across the United States were viewed as filthy slums filled with illicit activity. After World War II, however, there was a kind of rebranding effort. The US adopted the image of the new democratic leader, and China had been an important ally during World War II. As a result, there were efforts to financially invest in Chinatowns and to extend legal rights to Chinese immigrants. This was most clear in the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. There were also social investments as the media began portraying Chinatowns more positively, highlighting them as great tourist destinations. That’s the backdrop for the construction of the Chinese Merchants Association in Boston in 1949, which housed the headquarters of the association and a community recreation center….

It’s the first building in Chinatown that was “self-funded,” which means it was funded through neighborhood associations….Tragically, five years after its construction, a third of the building was torn down to make way for the Fitzgerald Expressway, leaving behind this not-quite-whole building that’s rife with memory, symbolism, and more.

…I’m curious about your reaction to the building. In some ways it’s very Chinatown: a patchwork of aesthetics, an obvious grafting of oriental ornament onto an otherwise Western building.

Dong-Ping Wong

Right now I’m on Google Maps, staring at the facade that got chopped off and replaced and laughing. It’s a weird way to finish off a truncated building. The new facade is very blank, with just one modernist strip window. It’s more modernist than any other building facade in the immediate vicinity. Its blankness is especially surprising because it makes the facade feel like the back of the building, but it faces a lot of traffic and a significant intersection. It feels like it’s waiting for something else to be built next to it.

On the front facade, I didn’t notice that they closed off those balconies until you mentioned it. I originally thought that there was nothing about the architecture itself, except for the pagoda, that felt immediately Chinese or Asian to me. In fact, it actually felt quite German. But when I zoom in on the enclosed balconies, I can see that there are columns inside and also that at some point the balconies were open to the street, to the outside. You see that balcony condition often in Manhattan Chinatown, and it feels much more contextual and part of the neighborhood.

I’m guessing that openness reflected the Chinese Merchants Association’s goals to be a part of the community, so closing it off feels not just like an aesthetic abandonment but also like an abandonment of community connectivity. Otherwise, the decorative elements, like the “Welcome to Chinatown” sign in that chop suey font and the planted pagoda on top, are what stand out to me. It’s funny because it feels like all of the remaining decoration exists from the roofline up, and my read is that the point of the ornamentation is to announce itself to people further away. After the renovation, the building itself became backgrounded.

It must have been so brutal to finish a building and then five years later have it cut off like that.

EH

It’s so brutal.

DPW

I’m sure it was a huge deal in Chinatown at the time. There was probably a lot of pride in the building’s construction. Then five years later, the association lost half of it.

I appreciate how you used the word rebrand to open this conversation. I’ve never thought of the shift in the US view of Asian Americanness after World War II in those terms before. I’m aware of it, but I think rebrand is a perfect way to describe it. The word is so concise, yet it also captures the treatment of Asian Americanness as a kind of product or service. This building is a good example of that. The Asian American community had a little bit of agency to create something for itself, until it was in the way of something that the city wanted. Once the product of Asian Americanness was no longer useful, the city took a bunch of it away.

EH

Chinatowns everywhere have always been vulnerable, and to some extent, their existence always feels conditional. You mentioned agency, though, which is important to talk about. Despite Chinatowns’ precarity, Chinatown does have some agency, and I wonder where you think that is and how it can be leveraged.

DPW

If I had a good answer to this, I would solve the problems in Chinatown. I will say that one of the nice things I’ve learned about Manhattan Chinatown over the last years is how community members of all ages are drawn to activism. Of course, it’s not always effective. For example, there’s a big new jail coming into Chinatown that the neighborhood has been protesting nonstop for years, and still, there’s a point where it feels like a losing battle.[1]

But there are other city projects that the community has been more effective in blocking.

This was surprising to me, given my incorrect assumption that Asian Americans are not that vocal. I’ve come to realize that there’s a lot of internal vocalness, but it’s very rarely broadcast outside of the community. Within the neighborhood, it’s amazing to see so many organizations, associations, and nonprofits being loud. Chinatowns across the US have always been relatively low-income neighborhoods, so I don’t think there’s much of a financial lever to pull. But there is a political lever that I think stops bad things from happening. I wonder whether the community can use that same political leverage to push for changes that benefit Chinatown….

EH

…I want to talk about the role of memory and symbolism within Chinatown. As with the Chinese Merchants Association building, the built environment contains markers of both joy and pain. How central are those symbols to a community or a neighborhood?

DPW

We’re working with two young Asian American clients on a diner project and one of the first conversations we had was about the question “What does Asian American architecture look like?” We were going to different Asian American restaurants as reference points, and we found two examples. One type of architecture resembles the Chinese Merchants Association building: East Asian design elements are clearly translated and grafted onto Western structures. Many classic Chinese restaurants fall into this category: they have very cute, tongue-in-cheek, Asian-like neon signs or calendars and waving cats, but without the ornament, the space and architecture could be anything. There’s really nothing inherently Asian or Asian American.

The other is an architecture that leans heavily toward the exaggerated orientalized architecture that almost becomes a caricature. Both are using this Asian aesthetic for survival’s sake, appealing to what the city wants, but I wonder if the second kind might be more difficult to tear apart or demolish because it has more romanticized Chinese elements. Whether superficially or not, cultural identity is infused into it. I’m thinking about our restaurant design and whether it’s possible to weave Asian Americanness into the bones of the architecture itself, through material, structure, or aesthetics, without the “oriental” look that’s only catering to tourists.

When I was growing up, I hated Panda Express. Actually, I really liked it, but I was never proud of Panda Express. I was ashamed when I went to the mall, because I thought, This is not real Chinese food. Only recently, maybe in the last 10 years, I realized it isn’t supposed to be real Chinese food. It’s Chinese American food.

I’ve been seeing a generation of younger Asian American chefs in the past few years making Chinese American food their own. I imagine something similar happening architecturally: we take an aesthetic that was done for survival’s sake, for tourists, and own it. Can we make it a genuine Chinatown culture aesthetic, which in this case would be referencing not purely American or Chinese aesthetics but a sweet spot that’s somewhere between kitsch, authenticity, and progressivism? I’m particularly interested in kitsch because it’s been very helpful to the survival of Chinatowns. I don’t think an Asian American style necessarily needs to have that tired oriental look, but I think the kitsch aesthetic is a useful tool. It’s like, “Look, we know this is appealing to you, so we’re going to use it. You won’t want to fuck with this building, but we’re going to make it our own.”

EH

It’s almost like an inside joke. While the architecture doesn’t actually reference cliched images of China, we play to our advantage on the assumption that it does. I was at dinner with a friend who’s Chinese, from China, and he told me that he loves going to Chinatowns when he’s in other countries. It’s not because he misses China or because Chinatowns feel anything like China but because they’re their own worlds. That sentiment is useful when we talk about what it means to preserve Chinatown and what exactly makes Chinatown Chinatown.

DPW

Maybe there’s a way to frame these shifts in three phases. I can imagine that when Chinatowns first emerged Chinese Associations were established to protect the neighborhoods. At that point, there were huge vulnerable workforces from China that were being villainized. It makes sense that Chinese Associations had reputations for being involved in illicit business dealings, because Chinese immigrants had few legal rights or protections. After the “rebrand,” after World War II, it feels like Chinatowns became marketing opportunities and started catering to tourists. This shift involved creating a version of Chinatown that was palatable and acceptable to outsiders. I think Chinatowns now are still in this second phase.

One of the reasons we’re having this conversation is because that phase is ending and there’s a new phase that has to—and hopefully already is—happening. To the question about aesthetics, I think my generation felt embarrassed about the kitschy overexaggerated oriental aesthetic, but it is true to how we grew up. Orange chicken, as much as it might not be authentic Chinese food or relate to where our parents came from, belongs to the world we grew up in. It’s just now becoming a source of pride, still with a slight tongue-in-cheek quality, but it’s becoming a source of pride. I want to believe that this shift in psychology means that we’re beginning to own the aesthetic that was originally made for others, and even use that to set some new aesthetics.

This new phase parallels the emergence of Asian American creatives within Chinatown who are integrating that cultural identity we grew up with into fashion, architecture, design, and food. I don’t know what you’d label that third phase, but I hope it’s happening.

Jeremy Ficca on Biogenic Materials: Where High Tech and Low Tech Meet

By the early 1900s, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had emerged as an industrial powerhouse, due in large part to its prodigious steel production. More than a century later, the city has refashioned itself as a center for innovation. It is thus fitting that Jeremy Ficca (MArch II ’00), an associate professor and incoming Associate Head of Design Fundamentals in the School of Architecture at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), has concentrated his research on biogenic building materials. Made from rapidly renewable resources such as plants and fungi, biogenic materials offer a sustainable alternative to standard materials such as steel and concrete, requiring less energy for sourcing and construction, and even assisting with carbon sequestration. This semester, as a design critic in the Department of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), Ficca is teaching an option studio called “Material Embodiment: Logics for Post-Carbon Architectures” in which biogenic materials—and geogenic materials, which are sourced from the earth’s crust—feature prominently.

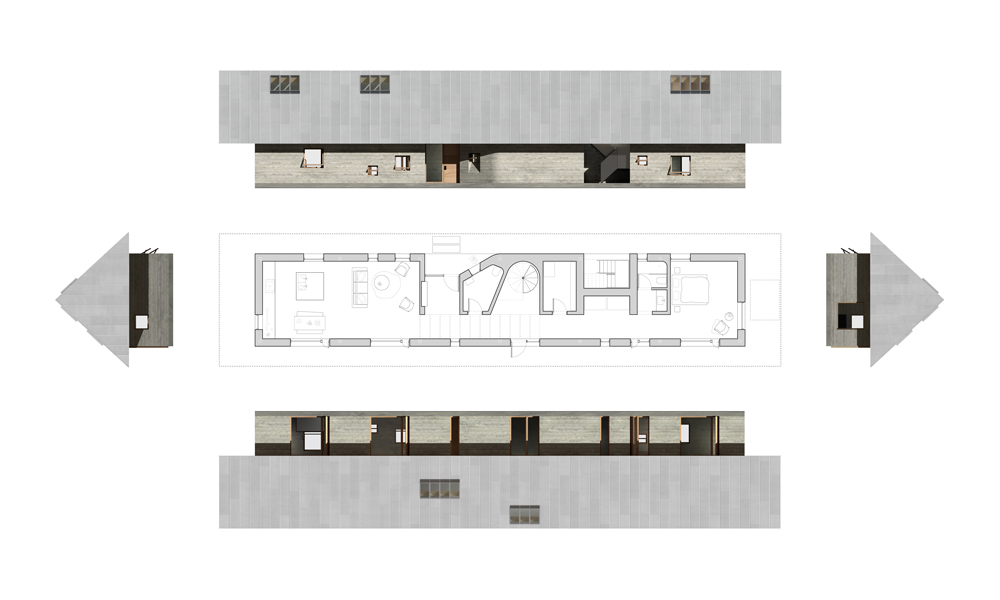

With respect to buildings, Ficca explains, we tend to think about energy and carbon in two ways. The first and more conventional outlook involves increasing energy efficiency for elements like heating, cooling, and lighting, often through technological means. The second relates to how and with what materials buildings are constructed, along with the externalities that accompany these design decisions, such as their impacts on human labor and greenhouse gas emissions. This more holistic approach underlies the “Material Embodiment” studio, in which students explore bio- and geogenic materials (such as hemp, straw, and earth) to design a hybrid workforce-training and research facility on an old river-front industrial site in Pittsburgh’s Hazelwood Green. The studio asks the students to rethink the material composition of a building as well as their designs’ broader implications on material sourcing, labor, construction technology, and maintenance.

Ficca recently spoke with Krista Sykes about bio- and geogenic materials, his own research, and the urgency for change within the architectural discipline.

How did you become interested in biogenic materials?

My teaching and design research focus on the intersections of materiality, technology, and architecture. While this initially operated within the field of computational methods of design and fabrication, material affordances were a common thread. As one who teaches courses and studios that focus on the materialization of architectural intent, I contend with the impact of building on our planet’s ecosystems through the carbon intensive and extractive nature of construction. Like many of us, I spent time during the pandemic looking inward. The writings of ecological economist Tim Jackson were an important influence on my understanding of post-growth and the imperative to transition to a more resilient economy and society. Around the same time, I was asked to reconceive a core material and construction course for graduate students in CMU’s Master of Architecture program. Doing so provided an opportunity to fundamentally rethink this content in relation to climate change and resilience. The questions that began to arise through the development of the course and subsequent discussions with students highlighted the inadequacy of simply trying to achieve greater and greater efficiency in building performance rather than exploring how the building’s material makeup can substantially reduce energy and carbon expenditures.

We are at a precarious moment. There is broad consensus that our climate crisis requires fundamental recalibration of the acts of building to address the negative externalities of the process. There is no single solution to this immense challenge. Responses will be quite different depending upon local circumstances. I am interested in how material practices can address questions of embodied carbon and energy and how these practices might open space for design imagination and architectural expression. This is a technical problem but also a deeply cultural question.

In the North American context, the most universal biogenic construction material is wood. But there is a remarkably rich range of harvested and grown materials alongside wood, including bio-resins, mycelium, and hemp, to mention but a few. Some biogenic materials belong to longstanding traditions of building, while others emerged through rigorous research and development processes. My current work focuses on industrial hemp and lime, often referred to as hempcrete. While the combination of these materials to construct walls dates back more than thirty years, it is somewhat analogous with straw and cob techniques that have much longer histories.

You mentioned that some of the biogenic materials being explored in the studio connect to longstanding building traditions. Could you say more about the materials you have in mind?

Some of the students this semester are exploring loam (earth and clay) construction. These are practices with long histories that were largely passed over because they were incompatible with industrialized building techniques. There is remarkable work underway by architects like Roger Boltshauser and Martin Rauch that seek to situate these methods within the technological circumstances of our time. This is in part a process of reconnecting with practices that were perhaps deemed to be pre-modern, inefficient, or even primitive. But this renewed interest does not result from nostalgia or a desire to return to pre-modern vernacular techniques. Rauch’s development of prefabricated insulated rammed earth blocks is a response to the challenges of scale, labor, and construction costs. As their work is demonstrating, adoption of these techniques will require automation to address their labor intensiveness. Additionally, there is research underway at the Gramazio Kohler ETH research group developing robotic deposition of clay to yield monolithic architectural elements. It is a fascinating melding of high and low tech, of high precision and lower-resolution architecture. I find these calibrations, frictions, and occasional contradictions to be both exciting and a source of opportunity, prompting questions about the cultural connections between how we conceive of our environments and the materials with which we build.

How did your research come to focus on hemp and lime?

In December 2018 the United States passed the 2018 Farm Bill, removing hemp with extremely low concentration of THC from the definition of marijuana in the Controlled Substances Act. Passage of the bill legalized the growth and processing of industrial hemp nationwide. As I researched industrial hemp, I was impressed by its remarkable attributes as a crop and its performance as a building material. Per acre, industrial hemp is one of the most effective CO2 to biomass crops.

The convergence of the farm bill and the performance capacity of hempcrete that was emerging through research in the EU pointed to opportunities for applications in the US. There is a track record of industrial hemp farming in the EU and UK with a few noteworthy examples of buildings that utilize the material. I was initially drawn to the labor-intensive nature of using hempcrete as a site-rammed material, and its potential to inform incremental, process-oriented approaches to construction within domestic architecture. I was interested in how a house might grow over time along with the harvesting and processing of material. This work, at the scale of the house, has transitioned into the design of discretized assemblies.

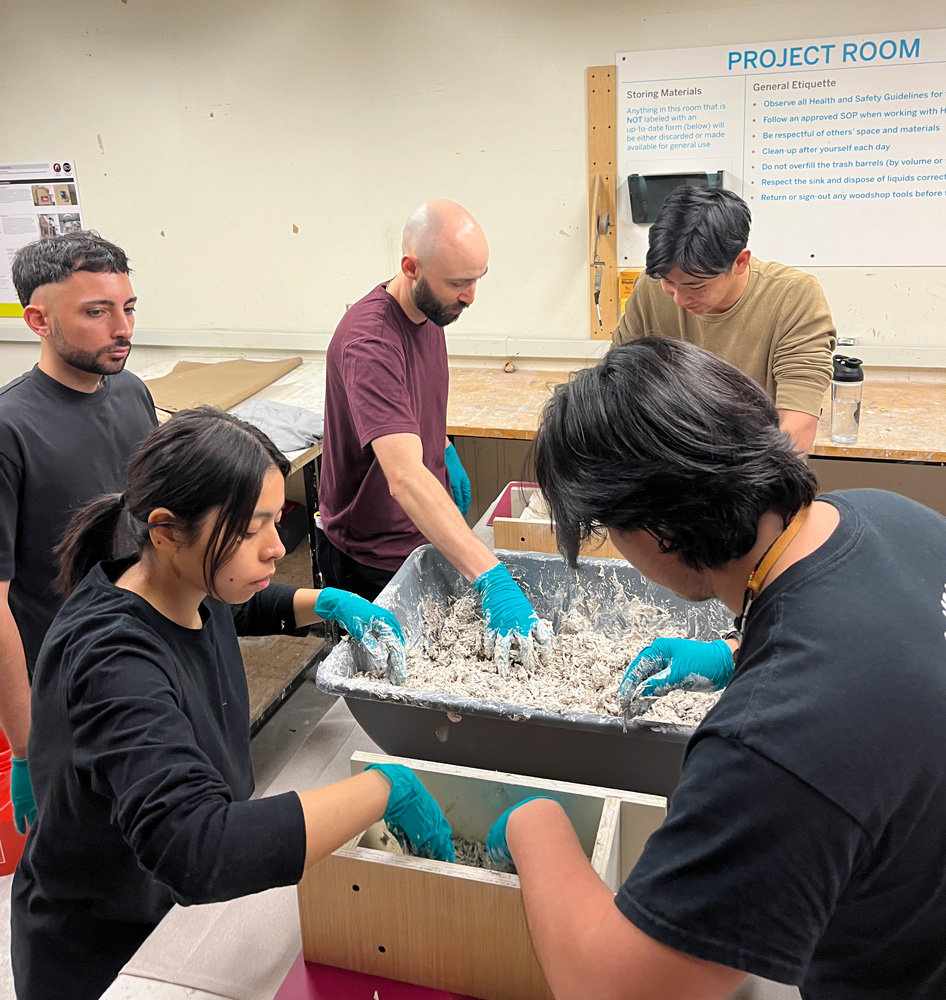

How does your work dovetail with the students’ pursuits throughout the semester?

The studio directs attention to one of the fundamental elements of architecture—the wall. We do so in part because many bio- and geogenic materials lend themselves to solid construction that relies upon accretion, processes of layering, compressing, and stacking. Materials like hempcrete and rammed earth require solidity and thickness to achieve thermal performance. But we also take on the topic of the architectural boundary because it reveals contemporary tendencies and desire. Principal among them is the legacy of modernism’s focus on lightness and thinness. The students are exploring spatial organizations and expressions that are informed and inspired by materials that require different processes of formation.

The students are developing proposals for a skilled workforce-training center located on a post-industrial site in Pittsburgh that was once a coke works and steel mill. It is a site with a long and complicated history of industrial growth, human labor, economic and environmental collapse, and regeneration. As I alluded to earlier, some of these materials are quite labor intensive. There are different attitudes to this topic. Some argue for greater human energy over embodied material energy and embrace the potential for the creation of new skills and jobs, while others point to automation to achieve scale and affordability. I am not advocating for one approach; rather, I’m interested in how the students’ positions on labor and technology inform their work. How might they calibrate architecture to production by humans and machines?

Very early in the semester we cast some hempcrete blocks. This experience allowed us to work directly with the material, understand the limits of its resolution, and appreciate the characteristics of a low-processed natural material. Hempcrete, like many bio- and geogenic materials, can be hard to control. It is inherently somewhat imprecise. This pushes back against the characteristics of most contemporary building materials, which tend to rely on high degrees of precision and predictability.

Another point of convergence between my research and the work undertaken in the studio this semester is the topic of durability. Most buildings are constructed to be highly durable, to withstand weather and time. And there are many good reasons for this; buildings are expensive to construct and maintain. Some of the materials we have been working with challenge that approach in that they can be understood as weak, or to require different forms of maintenance and repair. A lot of the ways in which one engages contemporary construction is to try to minimize those conditions in a building. Over the history of many cultures, there have been remarkable practices of maintenance and care, some that also have functioned as cultural acts in society. So, when we build with materials that are low in energy, low in carbon, as great as they might sound, there are certain tradeoffs, and perhaps one of the tradeoffs is the fact that they might require different forms of care and maintenance. Rather than this being perceived as a problem to be overcome, might there be an opportunity here? Might this challenge the way we think about a building’s lifespan and open new ways of considering the traces of time and the finishing of a building?

As low energy, low carbon, sustainable alternatives to conventional materials, bio- and geogenic materials offer exciting possibilities. It seems that reframing potential problems associated with these materials as disciplinary opportunities renders them even more promising.

I agree. I want to be careful not to oversimplify or generalize. Making even a small building is a complex endeavor that relies on hundreds of materials with a wide range of embodied carbon and energy. These questions need to be considered holistically to weigh tradeoffs. The material practices we’ve discussed raise fundamental questions about the status quo of construction and its impact on environmental degradation; in doing so they open space for imagination. I find this territory, coupled with the various frictions and complications, to be quite useful for students to operate within.

*All images by Jeremy Ficca, unless otherwise noted.

An Advocate for Architecture: Jhaelen Hernandez-Eli

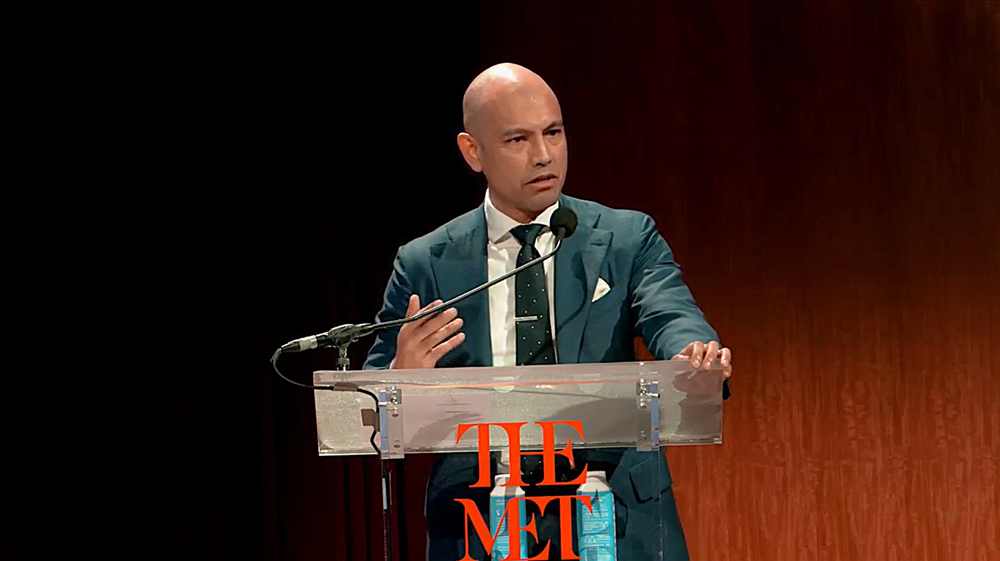

Nearly twenty years after his graduation, Jhaelen Hernandez-Eli (MArch ’06) will return to the GSD this spring to teach a seminar titled “The Art Museum: Typological Trajectories.” Hernandez-Eli is uniquely qualified to address this topic; as vice president of capital projects at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art , he oversees the institution’s $2 billion construction and renovation campaign, which includes the new Tang Wing for modern and contemporary art by Frida Escobedo (MDes ’12). Beyond his course-related expertise, Hernandez-Eli will share additional lessons about his work and the opportunities for owners to support the profession. “What I would love for students to understand is, that while I don’t practice architecture in the traditional way, the advocacy is still of utmost importance. There’s real opportunity for impact.” Rather than design buildings, Hernandez-Eli crafts processes that enable “an appropriate, robust, and rigorous architecture to emerge.”

Hernandez-Eli first arrived at the GSD in 2002, after earning a bachelor of arts in architecture from the College of Environmental Design (CED) at the University of California, Berkeley. The CED afforded him an understanding of architecture grounded in site and program, informed by environmental and social concerns. At the GSD, Hernandez-Eli encountered a different approach to architecture. In first-semester core studio, Scott Cohen (MArch ’85) assigned the “Hidden Room” exercise, a problem that mandates a covert fifth room be somehow obscured within four rooms. Hernandez-Eli found this exercise enlightening, as it exposed him “to the ideas of innovating within constraints beyond site and program and, more radically, of embracing those constraints.”

Over the next three years, a range of faculty—including Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), Monica Ponce de León (MAUD ’91), and Toshiko Mori—instilled in Hernandez-Eli additional foundational principles that, two decades later, continue to shape his work. These notions include an appreciation for architecture as interdisciplinary and socially embedded, not separate from the society that constructs it. Hernandez-Eli likewise developed a reverence for architecture and for the architects and craftspeople that make it. And he learned that, if properly positioned, he can design alternative processes within which architecture is produced, thereby bolstering architects, the power of architecture, and society at large.

The idea of designing processes has been instrumental in terms of Hernandez-Eli’s professional trajectory. While not practicing architecture in the traditional sense, he has constructed an impactful role for himself as an advocate for architecture. This began with his time at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, from 2008 through 2017, where he rose to an associate principal managing the studio’s operations and strategy, facilitating cultural projects such as the Museum of Modern Art expansion and the High Line. Hernandez-Eli then shifted from the service-provider to client/owner side, joining the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) as senior vice president, head of design and construction, where he spearheaded projects fostering social and economic equity, including public food markets and the city’s waterfront infrastructure. In 2020, after three years at NYCEDC, Hernandez-Eli moved to The Met where he oversees the design, architecture, and construction of the institution’s galleries, infrastructure, workspaces, and public areas.

At The Met, Hernandez-Eli has guided multiple projects such as the renovations of the Rockefeller Wing (by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture) and the galleries for Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art (by Tehrani of NADAAA). He also continues the larger undertaking he initiated with the NYCEDC: using his institutional role to demonstrate the opportunity owners have “to be bold, bringing in new voices and tackling the pressing issues of our time.” Most owners, he explains, approach the commissioning process in a risk-averse manner, choosing established firms with a well-stocked portfolio. Yet, Hernandez -Eli asserts, “if you know how to manage the project and build an infrastructure behind the scenes to mitigate such risks”—for example, pairing a younger architect with an experienced firm—owners can level the playing field for new voices. And while one might argue that customary design competitions offer newcomers a point of entry, Hernandez-Eli would vigorously disagree. “Competitions are terrible!” he declares. “Architects are undervalued and underpaid through that process. It also does not put the client in the best position to make the right decision.”

To illustrate how owners can design a process that supports less established architects, Hernandez-Eli references the example of Escobedo. As the New York Times noted upon her selection in 2022, “Escobedo, 42, is a surprising choice for such a major assignment given that she is relatively young, has mostly designed temporary structures, and is not a household name.” While these attributes might be deterrents for some, not for The Met. To settle on an architect for the Tang Wing, the museum adopted a workshop model, inviting a shortlist of relative newcomers to participate. Hernandez-Eli and others worked with the architects individually over the course of six months, meeting every two weeks, “getting to know them, guiding the process, helping them understand the constraints—just like the Hidden Room project.” In the end they chose Escobedo, stating in a press release that “her work draws from multiple cultural narratives, values, local resources, and addresses the urgent socioeconomic inequities and environmental crises that define our time.”

Alongside supporting newer architects, another opportunity for owners involves socioeconomic and environmental impact. For Hernandez-Eli, “design coordinates labor and materials around a set of values and manifests those values.” He continues, “engaging with architects who demonstrate a commitment to craft and artisanship, we’re looking to proactively curate the dollars [associated with our projects] into the local economy, local craftspeople, new technologies, so that we can participate in building a robust middle class.” This translates into job creation; for example, instead of importing artisans for a project, “we might fly them in to teach artisans here, who then develop new skillsets and become resilient themselves,” Hernandez-Eli explains. “It’s about keeping things hyperlocal, not shipping your granite in from Italy, but sourcing materials from within, say, a 50-mile radius,” thereby supporting regional suppliers and reducing the project’s carbon footprint. Hernandez-Eli’s larger message for owners? “Designers can’t maximize their impact alone. It is the responsibility of owners to set our designers up for success—embrace the work they’re doing and partner with them to choose how we spend those dollars.”

In a few months, Hernandez-Eli will help students explore the evolution of museum typology. Simultaneously, he will model non-conventional methods for championing architecture and architects. As Hernandez-Eli observes, “my story shows students that there are different paths to take, and there are different ways of advocating for architecture.”

The Body in Intimate Spaces