Design and Time: An Interview with Offshore

The public program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design features speakers in the design fields and beyond. The series of talks, conferences, and conversations offers an opportunity for the public to join members of the GSD community in cross-disciplinary discussions about the research driving design today.

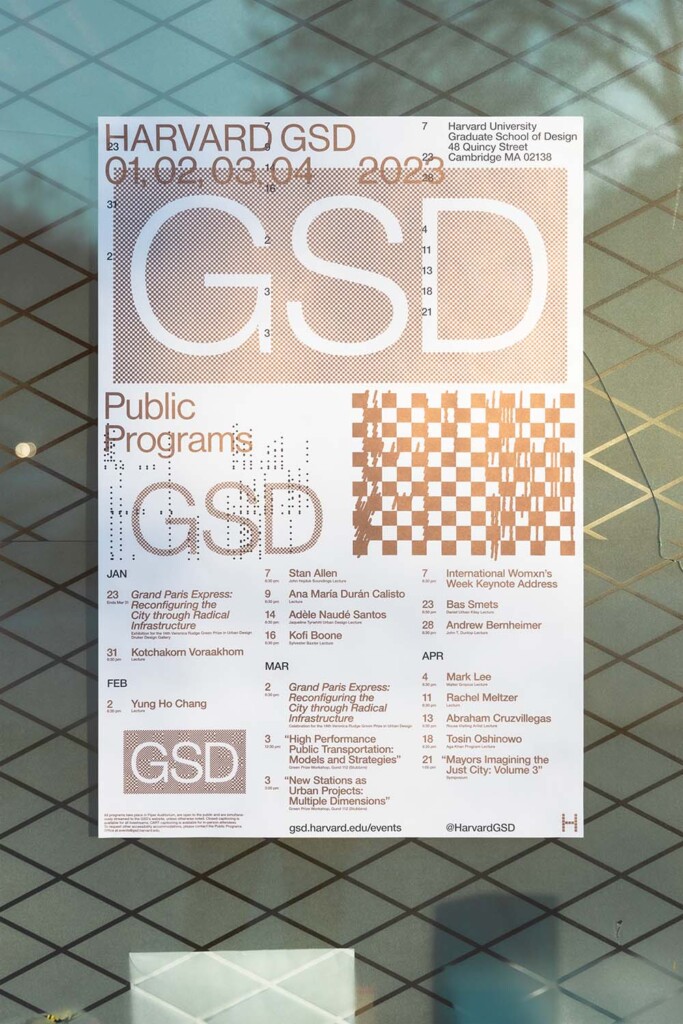

Each year, in an effort to extend an invitation to these programs as widely as possible, the GSD asks graphic designers to create a visual identity that conveys the program’s spirit and mission. For the 2023–2024 academic year, Offshore , the design practice of Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miler, took up that challenge. They created print and digital materials featuring a swirling motif and a spiral-like typeface that distill the energy and intellectual curiosity of the School’s events. To better understand how graphic design relates to the GSD’s public program, Art Director Chad Kloepfer exchanged questions with Miler and Seiffert over email.

Chad Kloepfer: Through innovative printing and custom typography, this year’s poster is a literal whirlwind of color and type. What did you hope to convey through this treatment?

Offshore: A whirlwind of color and type—that is such a nice description. The graphic language for architecture-related projects often features monochrome or more toned-down and serious visual gestures. Additionally, the pandemic years have felt very monotonous in many ways. We wanted to bring some energy and liveliness to this project. It was important for us to convey a vibrant, dynamic, and, to some extent, action-oriented mood.

There is a structured but organic feel to both the typeface and layout, the spiral being a predominant gesture. How did you arrive at this graphic device?

During the design process, we were very focused on striking a balance between sharp, clear, and bold graphical forms while allowing movement and avoiding rigidity. To us, this represents a commitment to precision that does not feel “square,” if that makes sense. The gesture of the spiral comes from the idea that this visual identity lives for one academic year, one cycle, so to say. It can be a very intense and dense period, with a lot of things happening at the same time. We wanted to convey that visually.

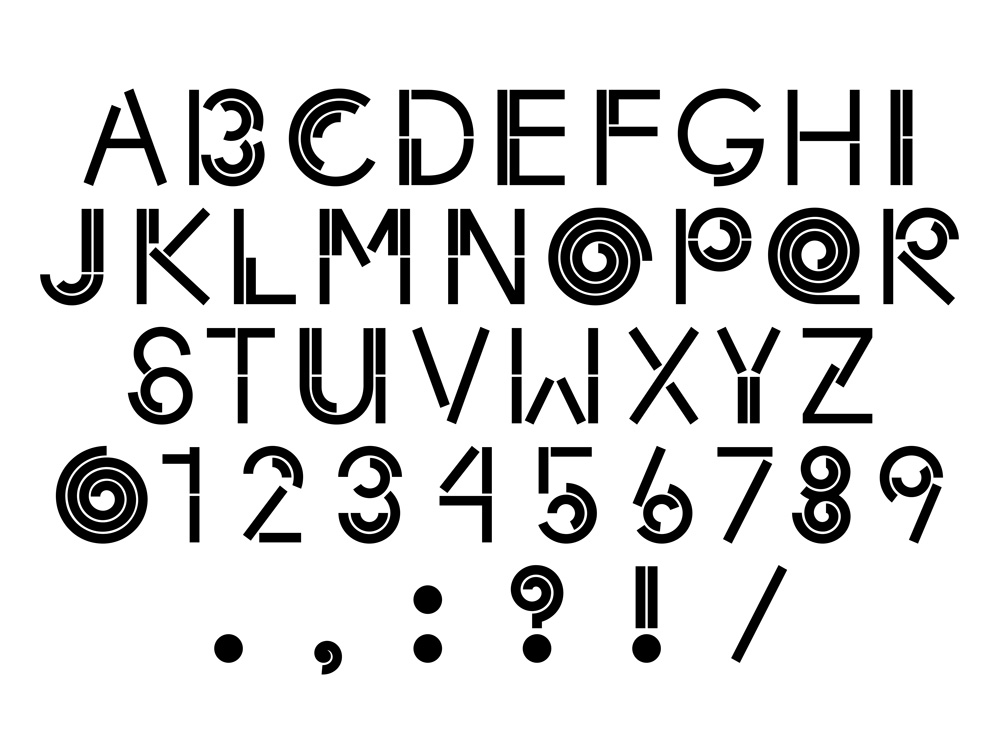

I really love the typeface, especially when the circular glyphs are animated. Can you speak a little bit about the development of this typeface?

There are quite a few typefaces out there that feature spirals in their glyphs. But all of those felt either too retro or too organic for this purpose. We were keen to be precise and playful at the same time–to simultaneously create something very constructed and quite dynamic. We made a few hand drawn sketches to find the general proportions and feeling. We also asked our friend Jürg Lehni, who created paper.js and the Scriptographer plugin for Illustrator back in the day, to create a small spiral tool for us. This made it easier and faster to draw very precise spirals with the parameters we needed for the various glyphs. We hope to extend the glyph set with lowercase and more punctuation later this year.

Could walk us through the printing process for the poster?

We used offset printing to produce the poster. This gave us access to radiant spot colors, which was essential for creating the vibrancy we were aiming for. The first step was to print the background layer and the big spiral in black and fluorescent red. The silver layer with all the typographic information cut-out was applied in the second step. This way the typography is displayed by revealing the first printing layer, thereby creating a vivid interaction of the overlapping elements.

Something I really admire in your body of work—and this year’s poster is no exception—is how layered it all feels. I mean this both visually and conceptually. Like a root system, we are taking in what is above ground, but it also hints to non-visible layers that are fun to unpack. Could you discuss the conceptual side of your process? What was the thinking behind this public program identity?

The deeper roots of our approach might be found in our latest fascination for the contemporary discourse around time. Today, many artists and writers are challenging the conventional Western idea that history moves in linear fashion. They are emphasizing the non-linear nature of time instead, thinking of history in loops, dialectics, time bangs, and spirals. For example, Ocean Vuong writes in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: “Some people say history moves in a spiral, not the line we have come to expect. We travel through time in a circular trajectory, our distance increasing from an epicenter only to return again, one circle removed.” We think many of those alternative notions of time are beautiful and fascinating, since they imply a more complex, long-term and intertwined relationship of humans, more-than humans, and the environment. In many ways, these concepts are counter-chronologies, challenging today’s prevalent version of standardized and linear time that serves efficiency, productivity, and a mainly economic perspective on progress and growth. These alternative, nonlinear views on time–some of them in the shape of a spiral–propose a less anthropocentric position, which might help us to synchronize ourselves with a world that is made up of multiple rhythms of being, growth, and decay.

Your portfolio has a striking visual range. Rather than following a set stylistic approach, you seem to generate a vernacular response to the subject matter of each project. What are the underlying continuities within your stylistically diverse body of work?

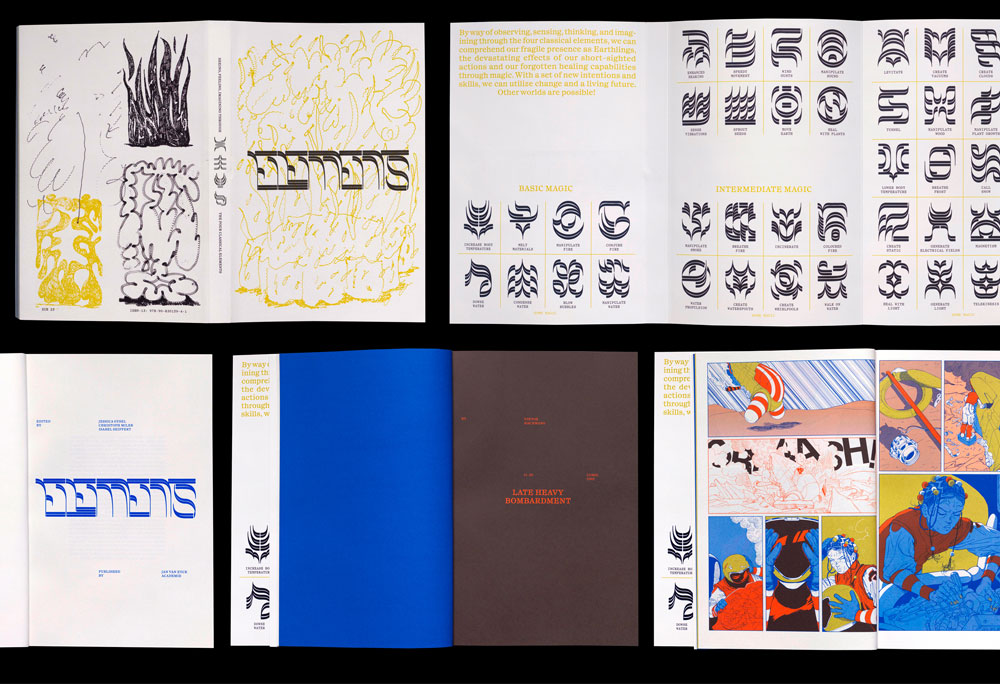

One underlying continuity within our work is our ongoing interest in multilayered narratives. Stories define who we are, sociologist Arthur W. Franke writes. They do so because they always “work on us, affecting what we are able to see as real, as possible, and as worth doing.” The aesthetics of each project develop from this and similar questions. What style communicates the story we want to tell? What tools do we need to use in order to create the aesthetics we envision? What production processes emphasizes our idea?

In the last five years, we have built manifold narratives, tackling issues ranging from migration, ecology, and interspecies relations to visual histories and design education. Working with various media—publications, websites, drawings, and exhibitions—we are interested in telling stories in an engaging, often multilayered fashion. Unfamiliar maps, vibrant visuals, symbols that expand and challenge the written language, photography, and illustration can coexist in our plots; they create rhythm, intertwine, and unfold unfamiliar perspectives. We tell stories by exploring, questioning, and transgressing the defined spaces of the discipline of Graphic Design while still staying committed to form, aesthetics, and craft.

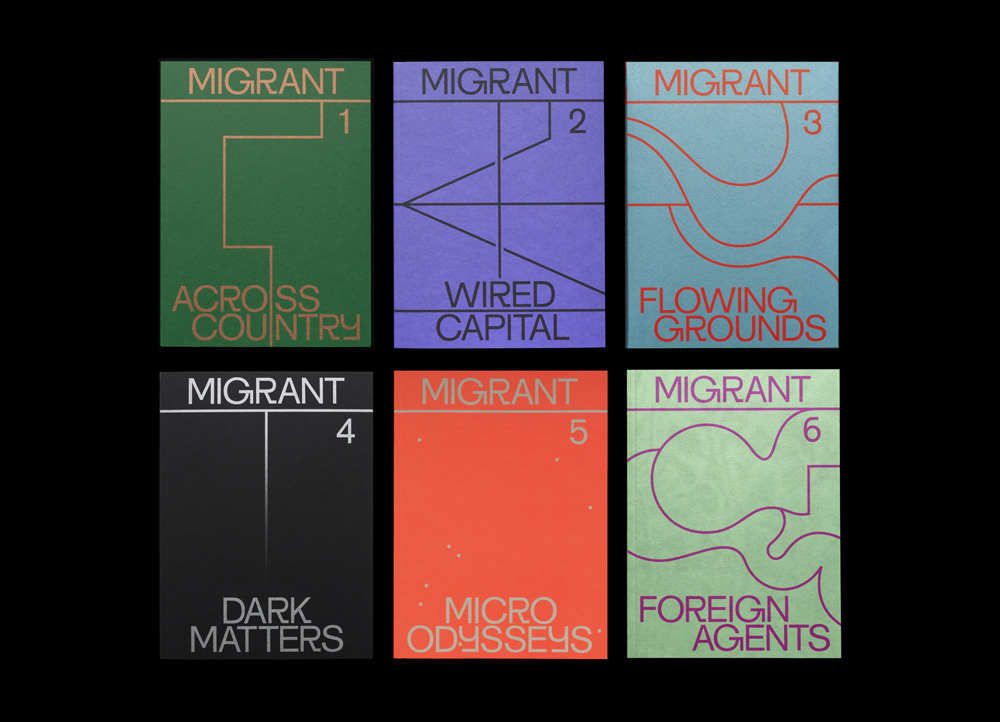

One of the projects that brought your studio to our attention is the publication Migrant Journal , which ran from 2016–2019. You were not just the designers of this publication but also helped found it and were co-editors. Can you speak a little bit about what Migrant Journal was/is and what it meant for your studio?

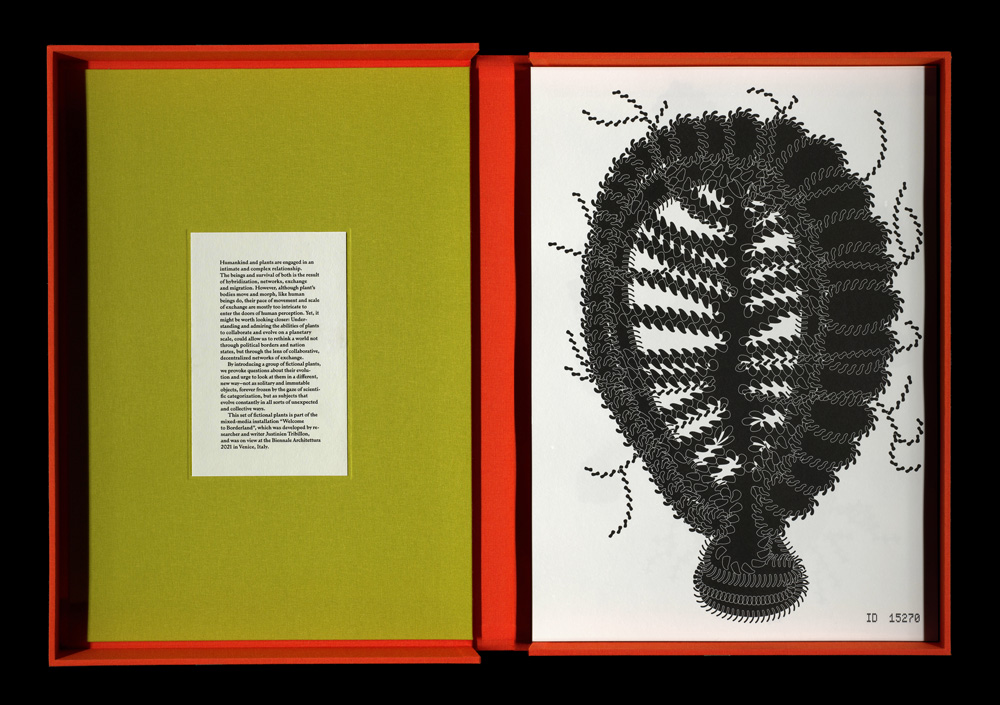

Migrant Journal was a six-issue publication exploring the circulation of people, goods, information, ideas, plants, and landscapes around the world. Together with our contributors, we looked at the transformative impact this circulation has on contemporary life and spaces around us.

Our endeavor with Migrant Journal has been from the start to look at the world through the lens of these migratory processes—dealing with questions of belonging, national identity, cultural shifts, financial systems, but also landscape transformation, the weather, movement of animals, and global food networks. The idea was born in 2015 when the so-called migrant crisis in the Mediterranean Sea was seemingly the only topic in the news. We felt that there was a huge lack of in-depth information about the complexity of the issue, global interrelations, and the broader concept of migration. In a world of a polarized and populist political climate and increasingly sensationalist media coverage, we felt that it is more important than ever to re-appropriate and destigmatize the term migrant.

In order to break away from the prejudices and clichés of migrants and migration, we asked artists, journalists, academics, designers, architects, philosophers, activists, and citizens to rethink the approach to migration with us and critically explore the new spaces it creates. A printed journal provided a platform for multiple disciplines and voices to talk about an intensely interconnected world that creates a multitude of interdependent forms of migration.

The decision to produce a magazine, and not make a website or a book, was purposeful. We strongly believe that printed publications can create a reading experience that lasts longer than most ephemeral bits of information on the internet. As soon as it’s online, it’s lost in the stream of information, and we didn’t want this. Print is still the technology that ages better than any other carrier of information.

Maps are an integral component of migration. They are all about movement, territory, and space. So it felt very natural to use the technique of mapmaking as a narrative tool for our publication. Maps, as one major component of Migrant Journal, are woven into a diverse set of editorial formats, like essays, images, infographics, reports, and illustrations. Through the materiality of the object we were able to translate complex issues into a format that provides various points of entries in a multilayered manner.

It’s our founding project and has heavily shaped our way of working in many aspects of the practice. At the same time, it defined our studio profile and influences, until today, the projects for which we receive commissions.

How Public Health Methods Can Bolster Socially Conscious Urban Development

Cities today are faced with complex challenges that require careful decisions about the future of the built environment. Development projects hold the potential to strengthen communities by helping to combat inequality, repair a legacy of environmental racism, improve health outcomes, and adapt to a changing climate. Developers, designers, and city officials alike need sophisticated tools and methodologies to ensure that projects can positively impact their communities while meeting the needs of all stakeholders.

In cities such as Boston, public review processes already exist that aim to foster conversation about the costs and benefits of new development; however, these processes can be slow and contentious. The field of public health offers new tools and insights that can help city leaders, community members, and designers understand the full range of impacts that a given project might produce. Adele Houghton , president of Biositu LLC and instructor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, has been working to bridge these fields for much of her career, most recently by applying a technique known as health situation analysis to real estate development. While pursuing a doctorate at the School of Public Health, Houghton collaborated with Matthew Kiefer, Lecturer in Real Estate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Their work resulted in the recent article “How Real Estate Development Can Boost Urban Health, ” published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Houghton and Kiefer spoke with the GSD’s William Smith about how health situation analysis can be a tool for aligning with the needs of communities, the business aims of real estate developers, and the mandates of city agencies charged with overseeing equitable development.

How did this project come about?

Matthew Kiefer The article grew out of a collaboration between Adele and me in a class I taught at the GSD last year called Developing for Social Impact. The premise of the course was to harmonize purpose and profit in real estate development and harness economically feasible projects to accomplish social and environmental goals. We used active Boston development sites as case studies, and student teams working on one site got very interested in the health situation analysis that Adele introduced.

Adele Houghton I reached out to Matthew because I was interested in the dual business model he presented through the course. I was a Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) student at the time, studying at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The DrPH degree is designed for mid-career professionals who want to translate research into action in the field. In my case, as an architect who has specialized in green and healthy building for about 20 years, I returned to school to learn how to apply public health methods to the design and real estate development process.

In architecture school you spend a lot of time learning about design, building codes, building engineering, and building systems. The business side is focused on how to create a firm; I wish I had learned more about real estate development. As part of my DrPH, I wanted to learn more about how real estate development happens: how you choose a site, how you decide what its highest and best use is, how you finance it. Matthew’s course did that—and brought environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into that financial calculation.

How does public health relate to real estate development?

AH The work we do as architects and developers affects not just the people inside the building, but also the surrounding neighborhood. Our colleagues in the urban planning and community planning departments are learning about those systems, but architectural design often focuses exclusively inside the property line.

When I pivoted to studying public health about 15 years ago, it was to learn more about methods and data sets that would allow architects and developers to fill in some of the gaps in the site assessment process. I wanted to look not just at how a project site connects to utilities, or whether we need to include a sidewalk along the edge of the site, but really at how a site leverages its surroundings to create a positive ripple effect in the community.

The core of your method is health situation analysis. Could you explain what that entails?

AH The methodology takes data sets and makes them actionable by providing design strategies that a developer or an architecture team could use in response to the conditions in the surrounding neighborhood.

Health situation analysis is already used by local health departments to assess what’s going on in a community and create an evidence-based plan for what to do about it. For example, the Covid-19 pandemic started in clusters around the country. We weren’t sure what it was. We weren’t sure how it was going to impact the community. We didn’t know who was going to be most impacted. Health situation analysis allowed local health departments to understand what was happening and make best use of their resources by implementing the smallest number of interventions—while ensuring that those interventions were not in conflict with each other.

We regularly do site assessments at the start of every design and real estate project. By incorporating health situation analysis into that process, we can pull together data sets to understand the demographics on and around the site, the environmental conditions, and the prevalence of underlying health conditions. For example, an elderly person exposed to a heat wave or power failure is at higher risk of going to the hospital than a younger, healthier person. Health situation analysis helps us tailor the design of an individual real estate project to support the health needs of vulnerable groups inside the building and in the surrounding community so it can have the biggest possible positive impact across multiple priorities–whether environmental, social, or financial.

What kinds of data sets do you look at?

AH When we perform a health situation analysis, we sift through publicly available data sets and look for trends in an entire population–whether inside the building or in the surrounding neighborhood.

We can divide the data sets we look at into three different groups. The first is called social determinants of health: factors outside a person’s own body that can influence their health. Most of that data comes from the US Census. Some people in our community are at higher risk of negative health outcomes because of their age—particularly young children and the elderly—or because they have less robust immune systems, such as cancer patients. We particularly assess factors related to how our society is set up—such as differences in access to health care, to clean air, to education, and healthy housing across income levels and the legacy of racist land use policies like redlining. Over time, those differences lead to disparities in health outcomes, and even in life expectancy. The social determinants of health help us understand which groups of people in the building and surrounding neighborhood are more likely to have a negative health outcome, say, if they’re exposed to a lot of air pollution, heat, or flooding.

The second category of data is community health indicators that are influenced by the built environment—such as asthma rates, cancer rates, mental health, and obesity rates. Every year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts representational surveys at the national level and then creates estimates at the census-tract level about the prevalence of those health risks.

The third data set relates to the health effects of climate change, and that’s mostly taken from an index created by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). It combines a list of about a dozen natural disasters with social determinants of health to analyze the vulnerability of a census tract to each hazard.

Combining these three types of data sets, we end up with a mosaic picture of a neighborhood’s current health conditions and potential risks that could be modified through design.

The paper describes three components of a design process that includes health situation analysis. You define these as data analysis, community engagement, and cost-benefit analysis. How do these aspects fit together?

MK Our article applies this methodology to the public approval process that every real estate development goes through. The larger the development, the more rigorous the approval process and the greater the opportunity to affect public health positively or negatively. Health situation analysis helps you understand how all the publicly available data applies to your site. That leads to decisions about how to design your project. And it can lead to changes in everything from building design, to programming, to mitigation commitments surrounding your site.

Health situation analysis is also a useful way to frame communications with neighbors and with community members who participate in the approval process, allowing you to explain why you’re designing the project the way you are. We use the example of a building that has reduced carbon emissions to adhere to a city-wide net zero mandate. If I’m living a block away, how much do I care about that city-wide mandate? But if there are high asthma rates in the neighborhood, and maybe my child has asthma, then the effect of the project on asthma rates might be a better frame for helping me evaluate the project. Health situation analysis is a way to ground those community discussions that every real estate development project has anyway in data that is specific to the neighborhood and informs the community engagement process.

Of course, the real estate developer’s primary objective is not to address public health in the neighborhood; it’s to develop a feasible project and in the process take prudent measures to address public health effects. How do you figure out whether given measures are sensible when you’re trying to harmonize those two objectives? Cost-benefit analysis is the standard way to do it. How much is it going to add to the capital or operating cost of the project and what benefits will it produce, even if those benefits flow to others?

It may be that the developer bears the cost while the benefits flow to the neighbors. But, if the developer is trying to make the case for density on the site, for public approvals, for financing from mission-oriented investors who care about social impact, then health situation analysis is a useful mechanism to test the efficacy of the measures the developer is proposing.

AH What you’re doing inside the property line is creating value beyond the property line. Health situation analysis helps expand the value proposition and answer the question: How could the developer and the design team benefit from providing benefits to the surrounding community?

How do you see health situation analysis mitigating broader housing problems specifically?

AH I’m talking right now to two city housing authorities that are interested in the idea of health situation analysis. They’re thinking about how a development project fits into larger systems, whether they’re environmental systems, social systems, or economic systems.

They consider questions beyond design and construction, such as: What do you do after the building is constructed? How is it operated? A lot of the benefit to the community happens after the building is operational. Affordable housing has to be an affordable place to live once you’re in it. It also has to be well-maintained with amenities like childcare facilities, a playground, maybe even a pharmacy or a primary care facility. We can’t think about housing as just the dwelling. It needs to be thought of as fitting into a larger system. Health situation analysis allows for that conversation to happen in a structured, data-driven way.

MK You could apply the health situation analysis methodology to any kind of project, but it’s particularly powerful for housing. In Boston and many cities with strong economies, housing attainability is a significant issue for many households. In Boston we’re creating jobs faster than we’re creating housing units for the people who are taking those jobs. That drives up prices for middle-income households, young families, first time home-buyers. Health situation analysis doesn’t solve that problem, but it can help overcome barriers to housing production by situating the public review and community-engagement processes in an evidence-based framework that communicates how a project is going to benefit a neighborhood. If this were adopted more broadly, it could help to ease the production of more housing to satisfy rising demand.

Your paper focuses on a case-study development site in Boston called P3. How were you able to apply the health situation analysis method in that instance?

MK P3 is a large publicly owned site in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston. It was cleared in the urban renewal era and has sat mostly unused ever since. It’s near Nubian Square, the heart of Boston’s African-American community, and across from a major transit node. The Boston Planning and Development Agency was doing a development competition—they’ve since designated a developer. So it was a fruitful case study site in my Developing for Social Impact course.

AH Boston is a great place to do this kind of project because it has an open data portal that has information on a wide range of topics related to the environment, social services, and demographics as well as a lot of qualitative information—interviews with residents in the Boston area. But the data sets are not interconnected. By doing the health situation analysis for P3, I was able to explain how that particular parcel situated within its census tract in Roxbury could help the city or at least the neighborhood address its high vulnerability to heat and its high vulnerability to flooding. The corner of the site is also located at an intersection with a high incidence of pedestrians and cyclists being injured by cars. It’s a place where a lot of elements intersect, but their relationship with each other is not obvious if you only look at each set of information separately.

The students in Matthew’s course picked up on how important it is to see the larger system. Matthew also made sure that the students had access to community members representing residents as well as businesses and institutions that were important in the neighborhood. There’s a real concern in Roxbury about displacement. The health situation analysis and conversations with the community helped students answer the question: How do you redevelop this important large site in a way that is responsive to the needs of the people that are already in that neighborhood, and help to bring jobs and economic opportunity and additional housing for them, while also recognizing that this could be an economic draw for other people in Boston?

Beyond the classroom, how have you been able to translate health situation analysis into real-world action?

AH I’ve been consulting throughout my career at Harvard. My dissertation, which was funded through the AIA Upjohn Research Initiative, was a proof-of-concept pilot working with three active real estate projects: one in Albany, New York; one in Buffalo, New York; and one in Waterford, Virginia. The health situation analysis is part of a larger engagement I call The Alignment Process, which uses health situation analysis as the first step in a multi-stakeholder conversation seeking common ground across three groups who often do not see eye to eye in the development process: the real estate development team, neighborhood residents and businesses, and local officials.

At the end of the process, stakeholders from all three pilots had co-developed aligned visions for their projects, as well as supportive design strategies. The process also produced metrics that the different stakeholder groups could use to keep track of the project and hold each other accountable to the actions to which they had committed to make sure that the project would achieve the agreed-upon vision.

One of my goals coming out of the pilot is to train designers, real estate professionals, local officials, and community groups so that The Alignment Process, and health situation analysis specifically, become standard practice. To that end, I have released a playbook walking stakeholders through the process step-by-step. With funding from the Boston Society for Architecture, Caroline Shannon (another GSD and Harvard Chan alum), and I recently ran the first two train-the-trainer workshops on this topic in Massachusetts. I’m also actively fundraising to turn the process of generating a health situation analysis, the data part of The Alignment Process, into an automated tool so that any designer, real estate team, community group, or municipality could make use of this approach.

MK One of the great virtues of the tool is that it brings stakeholders together. I sometimes describe the public approval process as a three-legged stool. The first leg of the stool is the proponent: the real estate developer or sponsor of the project, whether for-profit or nonprofit. Community stakeholders are the second leg of the stool. There are many community stakeholders and they have different viewpoints, but all of the outside parties affected by decisions about the project are part of the approval process. And the third leg of the stool is the public agency that approves the project. We try to make clear in the article that The Alignment Process generates benefits for all three of those legs of the stool.

It may be most obvious how the community members would benefit from health situation analysis. But project sponsors can also benefit by using it as an organizing framework for their mitigation decisions and discussions with project neighbors. It helps rationalize the approval process and can also benefit the way they do business and build relationships with their lenders and investors as well as their neighbors beyond the project.

The public agency also benefits. The approval process is often very contentious and it’s ultimately the public agency that needs to make a decision about whether to issue a permit. We live in a time of eroding faith in government as an effective agent of positive social change. In this environment, The Boston Planning and Development Agency—the agency most involved in development decisions for large projects—is eager to reach a successful resolution of development approvals, both so that worthy projects go forward, and to demonstrate its own effectiveness as an arbiter and decisionmaker on behalf of Boston’s citizens.

GSD How did the GSD facilitate this research?

AH It was an incredible experience for me as both an architect and doctoral student at the School of Public Health to be so welcomed at the GSD and basically recruited by Matthew as both a student and a teaching fellow in the course. The faculty here recognize their students’ strengths and the fact that so many students are experts in fields outside of design. They see that there’s an opportunity to incorporate broader fields of knowledge into the discussion around design. My more recent research on transdisciplinary curricula at the intersection of climate change, health, and equity reinforced my personal experience in Matthew’s course. There are very few schools that can provide this level of transdisciplinary education, and Harvard is at the top of the list, both in terms of having that capacity and actually starting to use it.

A Team of Harvard Researchers Develop a Prototype for a More Efficient and Eco-friendly Air Conditioner

Continuing a trend from this summer, September 2023 was the hottest September on record, according to scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. As climate change increases global temperatures, world cooling demands are expected to triple by 2050. While globally accessible and cheap to manufacture, conventional air conditioners still rely on wasteful mechanical vapor-compression methods and dated technology to cool and dehumidify air, making them one of the largest consumers of energy in industrialized countries. In response to these inefficient products and rising temperatures, an interdisciplinary team from Harvard is developing Vesma, a refrigerant-free, eco-friendly cooling solution suitable for all climates. In late August, their durable, low-cost, low-energy system was installed and tested in real-world conditions at HouseZero, headquarters for the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities (CGBC).

Vesma combines two innovative systems with imposing names: cold Superhydrophobic Nano-Architecture Process (cSNAP) and vacuum membrane dehumidification, often called “DryScreen.” By using just water, this advanced evaporative cooling technology can pre-treat and dehumidify the input air, further maximizing its cooling capability and allowing it to be used in a wide variety of climate zones around the world. A version of the DryScreen prototype will be installed at Druker Design Gallery as part of the exhibition Our Artificial Nature: Design Research for an Era of Environmental Change, on display from November 13 to December 21, 2023.

Early testing showed that Vesma effectively cooled indoor air in extremely hot conditions and could one day replace traditional vapor-compression coolers with a much more sustainable option. Jonathan Grinham, Assistant Professor of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), is one of the team leads working on Vesma. Grinham shared some test results with Joshua Machat, assistant director, communications and public affairs, at the GSD.

An interdisciplinary team from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Sciences (SEAS), Wyss Institute , and the GSD are behind the Vesma project. Could you explain the importance of this collaborative process?

The built environment and anthropogenic climate change are a deep causal loop. Designers need to untangle complex systems to re-think or even unlearn much of what we do, especially concerning a century-old way of conditioning interior environments. How we do this requires expertise across many fields. The GSD, Wyss, and SEAS faculty have cultivated a collaborative environment over the last decade or more. It has also had many different phases. Much of our early success came from translating problems. We found many interesting new technologies in the sciences looking for applications— solutions without the right problem. For example, the nanoscale barrier layer coating that allows indirect evaporative cooling in cSNAP was initially commercialized for waterproofing, anti-fouling, and other surface treatments. Not cooling. Or, in the case of the membranes for vacuum dehumidification, the engineering team built up expertise in making smart membranes for filtration; we simply asked if it could work for dehumidification. Spoiler: it doesn’t. But the expertise was on hand to quickly pivot to materials that were becoming more readily available and better suited for water capture. Today, the collaboration is in a different phase. Team members have a much better understanding of each other’s working methods and the value of collaborating. There’s far less of a “take and translate” mentality and more “yes and”: each side is better anticipating how this critical work benefits from other points of view.

The recent Vesma prototype was installed for two weeks in late August at HouseZero. Have you been able to conduct any early analysis from the collected data?

The team is thrilled with our early results. The field study goal was to prove we could effectively deliver refrigerant-free cooling in any climate using our novel vacuum membrane dehumidification and indirect evaporative cooling technology. We showed that the combined technologies, now named Vesma, can provide comfortable cooling more effectively than a typical vapor compression air conditioner. One way of proving this is by looking at the ratio of thermal energy removed to the electrical energy input or the coefficient of performance (COP). Vesma’s COP is above that of a typical air condition (COP > 4) and, under certain conditions, much, much higher. However, with any optimal system, we have to ask where things are less optimal. Vesma’s breakthrough is cooling using only water. The next big question was how much water the system uses for evaporative cooling. Throughout the study, we show that during certain conditions, the dehumidification system captures more water out of the incoming air than is used for cooling it. This is radical. However, on hot, dry days, we may only capture around 25 percent of the water we use for cooling. Finally, Vesma has a few ways of providing a thermally healthy environment. We can sensibly cool, we can dehumidify, and we can control the fresh air supply. We tested a half-dozen configurations to show we have several design degrees of freedom when providing a regenerative and effective cooling system. We’re excited to dive deeper into the data and see how to optimize for more human-centric cooling.

Is it possible for Vesma technology to be integrated into existing evaporative coolers in a cost-effective manner, especially with more industrialized systems?

This is somewhat a question of “market fit.” Our experience is that the building industry is a tough market to fit. Choose your “they” in the industry, but “they” have been doing things the same way for quite a while and making incremental improvements along the way. Vesma, and a few other companies we admire are disrupting the building cooling industry. We could integrate it into the existing system, but there is little appetite for it, especially when 50 percent of the market revenues are service contracts. Instead, we are targeting a cooling design that is a new or retrofit package for light commercial buildings (think replacing roof or wall units, not necessarily the mechanical penthouse). And not using refrigerants makes us even more disruptive. When it comes to market fit, it means we don’t have to sell through typical refrigerant-certified installers. Theoretically, any plumber, contractor, or handy owner can install Vesma because you just need to add water.

The water repellency of duck feathers is an inspiring phenomenon in nature that effectively insulates and cools various waterfowl. Can you explain the connection of down feathers and Vesma?

When we think about “new” materials, we think about a tiny fraction of society’s material history. The reality is that nature has evolved more beautiful and effective materials than we could ever design. For example, evaporative cooling is one of society’s first air conditioning methods used by “ancient” Egyptians and Persians. It’s a refined form of sweating, the same process that helps humans and other animals cool themselves through the phase change of water. In the case of duck feathers, whether contour or down, inspiration comes from the unique microstructures that enhance the bulk material’s performance. The contour feathers on the outside of the bird have a microstructure that locks the feather’s barbs together. This, combined with the duck’s own oils, which are worked into the feathers, creates waterproofing. In the case of cSNAP, we self-assemble a layer of alumina nanostructures on the ceramic and then functionalize them with an alkyl-group (oil-like compound) to make areas of the heat exchanger super hydrophobic and water-rejected. At the same time, other areas of the ceramic remain porous and hold the right amount of water for evaporation. Together, these dry and wet areas allow for powerful indirect evaporative cooling.

On the other hand, down feathers use small structures at the correct scale to trap air and create an insulating (and buoyant) layer. We think about the correct scale but do the opposite for both cSNAP and DryScreen. We design every feature in the system with tools like computational fluid dynamics to enhance heat and mass transfer. Effectively, we are trying to find geometry that promotes heat or vapor diffusion while limiting the energy needed to flow air across it, fitting form to flow. Typically, this means we are designing hierarchical structures with large surface areas—something closer to an elephant’s ears or a toucan’s beak.

Early refrigerants such as chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) have been phased out for environmental reasons and hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) have their own problems. It might be several years until a product like Vesma is on the market. In the meantime, what advice do you have for consumers who are seeking an environmentally friendly cooling unit?

Today’s HFCs have massive global warming potential (around 2000 times a single molecule of CO2). These chemicals typically leak before, during, and after an air condition system’s lifetime. The data are staggering. Societies’ global use of cooling (all cooling, not just buildings) has the potential to release many years’ worth of anthropocentric emissions by 2050; some say at least 60 Gtons of CO2e. For this reason, the Kigali Amendment outlines the gradual phase-out of HFC. This will likely happen with natural or organic refrigerants that have all been patented by the same slow-moving “they” mentioned above. Society found a good reason to phase out CFC, skin cancer. We are hopeful we can do it again with HFC. In the meantime, heat pumps using improved refrigerants are a good place to start. However, it can be more complex. As we rightfully push for more electrification, we must back it up with a larger and cleaner energy grid.

What is the greatest technological hurdle as this project advances and seeks project support and investment?

It’s exciting to say we know where most of our hurdles are. While we are in the very early productization phase, our collaborative team has driven Vesma’s discovery to an advanced level of development. The cSNAP indirect evaporative cooling unit was prototyped using industrial ceramic manufacturing with partners Gres Aragon in Spain. We have scaled up the barrier layer from a few square centimeters to many square meters (when you start designing something at the nanoscale, that’s more than ten orders of magnitude!). The bio-based polymers used in DryScreen have been tested and sourced with the industry. For the most part, the next phase of Vesma’s technical development will optimize the system-side design and integrate thermal controls (AI anyone). On the system side, we can certainly improve the vacuum pump; we expect three- to four-fold COP improvements using ready-to-ship pumps. On the thermal controls side, we are excited to distill enhanced thermal performance and optimal energy design into a single degree of freedom, simply asking the user, “Are you comfortable?”

Beyond Zoning: A New Approach for Today’s Cities

The early 20th-century zoning paradigm has outlasted its usefulness for 21st-century cities. Harvard GSD’s Matthew Kiefer argues for a more flexible—and democratic—approach to urban development.

Zoning arose more than a century ago after decades of urban expansion. Zoning rules governed land use—separating heavy industry from housing—and subjected buildings to uniform dimensional standards to help balance competing urban needs. Today, cities in general, and Boston in particular, are very different places: hubs for knowledge and culture instead of manufacturing. Zoning laws once meant to ensure orderly growth for industry while encouraging homeownership are coming into conflict with the need for housing, green development, and other urban imperatives.

Matthew Kiefer, a Lecturer in Real Estate at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), says that Boston is well-positioned to pioneer a more dynamic approach to regulating growth, replacing fixed zoning rules with nuanced development impact review for apartment buildings, labs, hotels, and hospitals. The impact review process, he argues, makes large developments subject to rigorous public oversight rather than the whims of nearby property owners. Kiefer lays out his argument in a chapter of the new book Idea City: How to Make Boston More Equitable, Livable, and Resilient (2023), edited by David Gamble. Kiefer spoke with the GSD about Boston’s urban aspirations, the history of zoning, and the future of socially engaged real estate development.

GSD: Why is reform to the zoning paradigm necessary now?

Matthew Kiefer: After a long late-20th-century decline, cities are reinventing themselves for very different purposes—knowledge, innovation, culture, and entertainment. People expect very different things from cities today. Some, like Boston, are lucky to be growing. But archaic zoning rules impede that growth and prevent its benefits from being shared more broadly.

How would you characterize Boston’s current approach to zoning, and why do you think it’s an obstacle to building an equitable city?

Virtually every US city has comprehensive zoning, with Houston as the famous exception. Boston has been a zoning innovator, but Boston’s innovations have merely adjusted the 100-year-old zoning framework. They’re patches on an overall system that no longer fulfills its intended purposes, if it ever did. Boston has not been able to overcome zoning’s fundamental flaws: inflexible rules that impede urban adaptation and empower self-interested abutters in a way that’s anti-democratic.

Why do you think the basic zoning paradigm doesn’t accomplish its intended purposes?

The basic idea of zoning comes from an effort at the US Commerce Department, just after World War I, to try to harmonize housing—and especially homeownership—with industry. Starting really after the Civil War, cities began exploding as places of manufacturing, abetted by railroads, port facilities, and mechanization. Before the automobile, workers lived near where they worked, which created tremendous land use friction. It’s not good to live next to a slaughterhouse or a foundry.

Those conflicts led the US government to propose what we now call comprehensive zoning. They published a standard state zoning enabling act that many states followed. The zoning paradigm had two components. First: let’s carve a city up into use districts to make sure industrial enterprises don’t get mixed together with single-family houses, and establish uniform dimensional requirements for buildings that serve those uses—height, amount of floor area, setbacks, etc. Second, let’s require any landowner who wants to do something that doesn’t conform to those rules to convince a citizen body, called a board of appeals, to grant a waiver based on proving that the property in question is uniquely disadvantaged by the rules.

That was the basic zoning structure that originated in the 1920s: uniform rules by district and a very high bar to justify any departures. We now have plenty of experience showing that that paradigm does not work in re-urbanizing cities like Boston that grew up before zoning. Zoning has often been used as an instrument of exclusion—a way to restrict newcomers, especially if they’re not like you. Besides that, it’s impossible to devise an after-the-fact set of rules that works in cities that have already been settled for centuries. You might be able to make rules that stick for a new suburb in a corn field, but how do you do that in a quirky, textured city like Boston? Add to that the city needs to adapt—to become more livable, equitable, and resilient. So there’s just no workable set of rules to govern how things get built that doesn’t require many exceptions from those rules.

Why can’t zoning boards simply issue the needed exceptions?

In zoning-speak, they’re called variances. The problem is that, even if you can convince the Board of Appeal to grant the ones you need, any nearby property owner who disagrees with the decision of the board can challenge it in court, and likely win. I argue that the process is anti-democratic. Any significant project in Boston goes through a very public process of vetting its potential impacts on its neighbors. You change your project design in response to what you heard, adopt mitigation measures to lessen impacts, and agree to provide public benefits for the impacts you can’t eliminate before you ask for your variances. By that point, the public has spoken in a very democratic way.

It only takes one abutter, who may be totally self-interested—you’re going to block her view, you’re going to create more traffic on his street—to challenge that public body’s grant of zoning waivers. So, in effect, one self-interested voice cancels the result of a democratic process.

Are there particular types of projects that run up against zoning challenges?

All privately built projects are subject to zoning. Most large projects in Boston need zoning variances. The projects most likely to attract challenges are those that are different in character or larger in scale than what’s around them—especially if surrounding uses are residences.

But not always. In my book chapter, I give an example of a non-profit developer proposing supportive housing for people experiencing chronic homelessness. The developer went through a lengthy process to receive a variance, and a landowner whose property across the street was used as a microbrewery sued to challenge it. He didn’t think the project—designed to serve a population with negligible rates of car ownership—had enough parking. That’s how the current zoning paradigm works: a single business owner could challenge this exemplary project because he thought it would take away street parking from brewery customers.

What are the consequences of these legal challenges for developers working on a project?

A legal challenge to zoning relief can take years to resolve. And often the project sponsor can’t beat the challenge. In order to win, the sponsor has to show unique characteristics of the property that result in the zoning rules not working. That’s hard to do in most cases—the zoning rules don’t work because they just don’t work, not because the property is different.

What’s the alternative? How can you create a more livable city while also addressing the real concerns of neighbors?

Development impact review can take the place of zoning relief. Impact review didn’t exist in 1920, when the current zoning paradigm was framed. It started at the federal level with the National Environmental Policy Act, in 1969. That law was translated into state-level environmental review laws, and then many cities like Boston developed their own impact review ordinances. They’re all based on the same concept: before a public body takes action on a project—grants approval or funding—the project sponsor has to study its potential impacts in a public forum following an iterative process.

The sponsor submits a series of increasingly detailed project reports. At each stage, public agencies, advocacy groups or any member of the public can comment. With help from specialized consultants in different subject areas, the sponsor publishes detailed studies in response to those comments. The studies sometimes demonstrate that the suggested impacts won’t occur, or if they are likely to occur, the studies quantify them and the sponsor proposes measures to mitigate them. Some impacts are unavoidable; 500 housing units next to a transit station will increase demand for transit, and may create shadows on a nearby park at some times of day. So the sponsor proposes public benefits to compensate for the burdens that can’t be eliminated. And eventually you approach consensus that your project merits approval.

As a sponsor, once you get to the end of that process, you’ve put your project out there in public forums. You’ve responded to the concerns you’ve heard in those forums with technical studies and project changes. You’ve entered into a set of binding agreements on mitigation measures and public benefits. The process isn’t perfect—not everyone gets what they want– but it’s very rigorous. It often takes, literally, years. Once you’ve completed it, there’s no reason you should need zoning waivers. If you’ve accounted for your project’s impacts in a very nuanced, project-specific way, what purpose does it serve to judge your project against uniform zoning rules designed to avoid impacts?

So that’s my solution in a nutshell: projects that go through impact review should be deemed to comply with zoning, regardless of whether they conform to the rules. The uniform zoning rules would still apply to homeowners, small business, people doing small, simple things that don’t warrant impact review, but even they could opt in. And, by the way, the rules should be more permissive, especially of multi-family housing, given Boston’s housing shortage.

What changes would need to happen and at what level to implement this kind of reform?

Boston’s zoning enabling statute gives it latitude to do this without going back to the legislature. Development impact review already exists in the Boston zoning code. If the Boston Planning and Development Agency and Zoning Commission were convinced this was a good idea, they could adopt a zoning amendment to put it in place.

What role will urban planners and real estate professionals play in the future growth of cities?

Cities are evolving more rapidly all the time in response to technological advances, social change, environmental imperatives and, lately, a pandemic. So it’s much more important for urban environments to be designed thoughtfully, and for land use to be regulated nimbly. Cities need to accommodate more versatility and adaptability—even some improvisation. The zoning paradigm of having a uniform set of rules that are hard to change and difficult to get relief from is increasingly obsolete given the way cities work today.

In this dynamic environment, real estate development is increasingly recognized as a social endeavor. Most of what gets built in cities is built by private actors—for profit and non-profit developers, hospitals, and universities like Harvard. The things they build affect many people and will hopefully be versatile enough to last a long time. They need to both meet the needs of their sponsors and account for their impacts on others. Development impact review is a key tool for achieving that. So to be successful, real estate professionals have to be social entrepreneurs; that’s why social impact is embedded in the GSD’s new Master in Real Estate Program. Professionals have to understand how to create places that accommodate changing aspirations for how people want to live and work—to be responsive and responsible city-makers.

How Designers Can Help Keep Our Air Breathable

Smoke from wildfires raging in Canada blanketed the Northeastern United States this month, turning the skies an eerie orange. Responding to record-setting levels of pollution, officials around the region declared health emergencies. Advice to close windows and run air filters helped mitigate the acute effects of the short-term crisis, but the event also drew attention to how climate change is intensifying chronic air pollution around the world.

Ensuring the safety and quality of air is now an urgent issue for designers. Holly Samuelson, Associate Professor in Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), is changing how the design fields think about the complexities of air quality. Protecting inhabitants from outside pollutants is only one part of the challenge. Buildings also need to have proper ventilation and provide efficient heating and cooling systems that could lower the emissions driving climate change in the first place. Samuelson shared her insights with William Smith, editorial director at the GSD.

William Smith: With this wildfire smoke offering a possible glimpse into a future of more frequent disasters stemming from climate change, what are some possible solutions the design fields could offer?

Holly Samuelson: With good design, buildings can be more airtight when desired to keep out smoke and other pollutants. As a bonus, reducing unwanted air leakage also increases thermal comfort during the winter and tends to be one of the most effective energy-saving measures in buildings. Improved airtightness requires good window selection and architectural detailing, especially at corners and joints between materials. There’s room for advancement here. It also requires a well-constructed building, so architects often specify air leakage limitations to be verified with on-site testing.

Of course, a more airtight building then requires better protection against indoor sources of pollution (If you give a mouse a cookie . . .) So, during periods of acceptable outdoor air quality, which is most of the time in many places, this means bringing in outdoor air to flush indoor pollutants, carbon dioxide, and airborne pathogens, a topic that needs little introduction since the onset of COVID. Design solutions are definitely needed here. How can we achieve the health benefits of more fresh air without all the carbon penalties of heating, cooling, and dehumidifying this air, moving it around, and constructing these systems in the first place? Cue the genius designers!

So what strategies have been used in buildings?

In Harvard’s Center for Green Building and City’s HouseZero , a naturally ventilated lab building, windows open automatically in response to measured air quality conditions. In buildings like the Chesapeake Bay Foundation Philip Merrill Environmental Center or the Artist for Humanity Epicenter, simple lights alert occupants when it’s a good time to open windows. Architects then design for good buoyancy or cross ventilation when they want to move abundant fresh air naturally.

Design teams also use energy recovery ventilation to allow heat and humidity exchange between incoming and outgoing air and to promote ventilation at times when window opening may be unpopular, like in winter. This energy recovery can be via heat exchangers, enthalpy wheels, or with small, ductless, through-the-wall units. Some design researchers are also working on passive versions of these systems, and others are advancing ultra-efficient radiant systems that focus on heating or cooling people rather than air in the first place.

Filtration is also an important topic that gains increased attention during wildfires. For buildings without mechanical ventilation, occupants can use standalone air filtration. Since pressure moves air through filters, and the higher the filtration efficiency, like MERV (minimum efficiency reporting value) 13 or HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) filters, the more air pressure that’s needed, and that takes fan power. Therefore, in mechanically ventilated buildings, designers can choose efficient equipment and remove other pressure losses in the system to avoid adding even more fan loads, for example by allowing for straight air paths with minimal surface area for friction. (Think boba tea straw, rather than curly straw for a thick milkshake.) This strategy takes space planning early in the design.

What other considerations should architects account for when creating efficient, ventilated buildings that also protect against pollution?

If we expect building occupants to close windows in unhealthy outdoor air conditions and to open windows in unhealthy indoor air conditions (a frequent problem in unventilated buildings), then issues of thermal comfort and safety matter, especially in residential buildings. This is especially important for occupants who are physiologically more sensitive to indoor overheating and poor air quality, such as young children and older adults. Architectural strategies like good sun shading, including trees, envelope insulation, and thermal storage, can reduce energy use while significantly extending the length of time that a building can remain comfortable in extreme weather conditions and power outages, an increasing concern with climate change.

Interview with Toni Griffin: A Spotlight on the MDes Degree Publics Domain

How is a public constituted, both spatially and socially? How does the public become legible and desirable? For whom does it exist? These are some of the questions that animate Toni Griffin’s proseminar “Of the Public. In the Public. By the Public” at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). Toni Griffin, Professor in Practice of Urban Planning at Harvard GSD, specializes in leading complex, transdisciplinary planning, and urban design projects for multi-sector clients in cities with long histories of spatial and social injustice. The proseminar course draws from scholars, practitioners, and urban planners to build foundational intelligence and provocative interpretations of the plural meanings of public.

Griffin is Domain Head for Publics, one of four concentrations in the Master in Design Studies (MDes) at GSD. The program challenges conventional ways of learning and prepares students to understand how design shapes and influences the underlying processes of contemporary life. The program is uniquely situated at the GSD to draw on insights from a multitude of fields and expertise to break down the silos between disciplines and develop a holistic understanding of complex issues. Through fieldwork, fabrication, collaboration, and dissemination, the program is aimed at those who want to develop expertise in design practice while gaining tools to enable a wide range of career paths. Students select one of four domains of study—Ecologies, Narratives, Publics, and Mediums—and undertake a core set of courses, including labs, seminars, workshops, initiatives, publications, and ongoing projects that connect advanced research methods and related topical courses. Uniquely, trajectories within each domain allow students to construct their own interdisciplinary tracks and take part in course offerings across the GSD, as well as other schools and departments at Harvard.

Many of these core concepts resonate with Grffin’s practice. She is founder of urbanAC , based in New York, and leads the Just City Lab , a research platform for developing values-based planning methodologies and tools, including the Just City Index and a framework of indicators and metrics for evaluating public life and urban justice in public plazas.

Harvard GSD’s Joshua Machat spoke with Toni Griffin about the MDes program, open projects, and how the Publics domain set out to explore the socio-spatial design, planning, implementation, and advocacy.

Joshua Machat: Why do you think the Publics domain is of interest to architects who are still in the early parts of their professional careers?

Toni Griffin: They appear to be architects who are no longer satisfied with traditional modes of architecture, which tend to focus on the building and the outcome. They’re more interested in the forces that shape architecture and the built environment. And they’re interested in the impact of that architecture on society, people, and place. Architecture, particularly in its pedagogy in undergraduate and graduate programs—and sometimes even in practice—doesn’t address those issues sufficiently. I’m finding that applicants are looking to round out their understanding of how the built world is produced through architecture and/or other disciplines. Who is involved in that work, who’s impacted in that work, who does that work benefit, and who gets to decide, are all part of their curiosities.

Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary thinking is a critical part of contemporary problem-solving in design. Can you explain how this approach is integrated into the Publics domain?

I do it perhaps in a couple of ways in the proseminar, which is divided into six modules. “To be Public”, which is about how we bring our individual identities, cultures, and backgrounds into the public realm. “Of the Public”, which is about the data, knowledge, memories, that we place into the public realm. “By the Public”, which is about public governance. “For the Public”, which is about the things that the public sector provides for society, cities, and neighborhoods. “With the Public” is about engagement, participation, and power. “In the Public” is about how creatives and designers place things in the public realm.

We have two guest speakers who come and speak on each of those modules. They tend to come from two disciplinary perspectives: two different disciplines are in dialogue about a particular topic every other week. Secondly, the students are put into teams, and they have to co-facilitate a class where they lead the discussion, not me. This requires them to work together. Because the students come from different backgrounds and experiences—whether different genders, ethnicities, nationalities, or disciplines—they often forge a cross-identity and cross-disciplinary collaboration.

The advance of the just city is at the core of your Publics proseminar. The Mayors Imagining the Just City Symposium was held in April and MICD Fellows discussed strategies for using planning and design interventions to address racial injustice in each of their respective cities. How did this conversation support the Publics proseminar learning objectives?

The Mayors Imagining the Just City public event is a part of the Mayor’s Institute on City Design (MICD) Just City Mayoral Fellowship program, which I lead through the Just City Lab. This is the third year of the fellowship in which eight mayors participate in an eleven-week online curriculum centered on best practices and examples of how urban planning, design, and development—the work that mayors lead—can achieve greater social and spatial justice.

During the closing session, when the mayors come back to Cambridge to present their projects and get feedback from eight resource experts, we end the program with a public program and presentation to give the GSD community exposure and access to city leaders and the roles that they play in building cities in collaboration with practitioners of the disciplines we offer at the GSD.

The learning objective is to create greater understanding around how public government, and specifically mayors, lead and shape this type of work. The event exposes students and the rest of the GSD community to the complexity of decision making around resources, choices, policies, and priorities that are helping to address issues in chronically disinvested neighborhoods and/or populations that have historically been marginalized through racially exclusionary and discriminatory practices.

It’s always my interest to expose students to other modes of practice, like the public sector, and the ways in which architects, landscape architects, and urban planners might find themselves situated in a public sector role—even running for mayor—and the ways in which their expertise can be useful within government, and not always as a consultant to government.

What do you think are the most distinguishing qualities of the MDes degree program at the GSD?

What makes the MDes program so attractive to students, and to me, is that it’s the most entrepreneurial design degree that we offer. Being a part of the program requires students to be comfortable with self-directing their journey through the four semesters. Students’ ability to choose a substantial number of your courses, across the departments at the GSD, across Harvard, and even some at MIT, is just amazing. It parallels how you might do a doctorate. It’s very self-directed. The beauty is in all the choices you get to make to inform your own intellectual curiosity. The challenge of that is all the courses on offer that you just won’t have time to do. It’s an embarrassment of riches and an extraordinary luxury students have that sometimes causes them a little bit of angst. But ultimately, they end up quite satisfied with the volume of choices.

I also like that the program includes students who have been out in the world working for some time alongside some students who are just coming out of their undergrad. I think that world experience, whether it’s two years or fourteen years, adds a lot to the depth of conversation. Students don’t realize that we as teachers are just as engaged in what they bring to the discussion as we give to them; in fact, it is a reciprocal relationship that makes for the best classroom environment.

The GSD is one of the most student-engaged design programs that I’ve ever been a part of. Students are very proactive through clubs, volunteer efforts, the production of their own events, and discussion groups. That brings a unique energy to the school and can drive change within the school. Students have a level of agency that allows them to feel very connected to each other and the GSD community, both during their time in the program and even after as alumni.

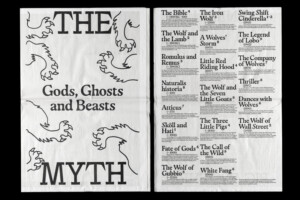

Ryan Gerald Nelson on Designing Iconic Typographic Moments

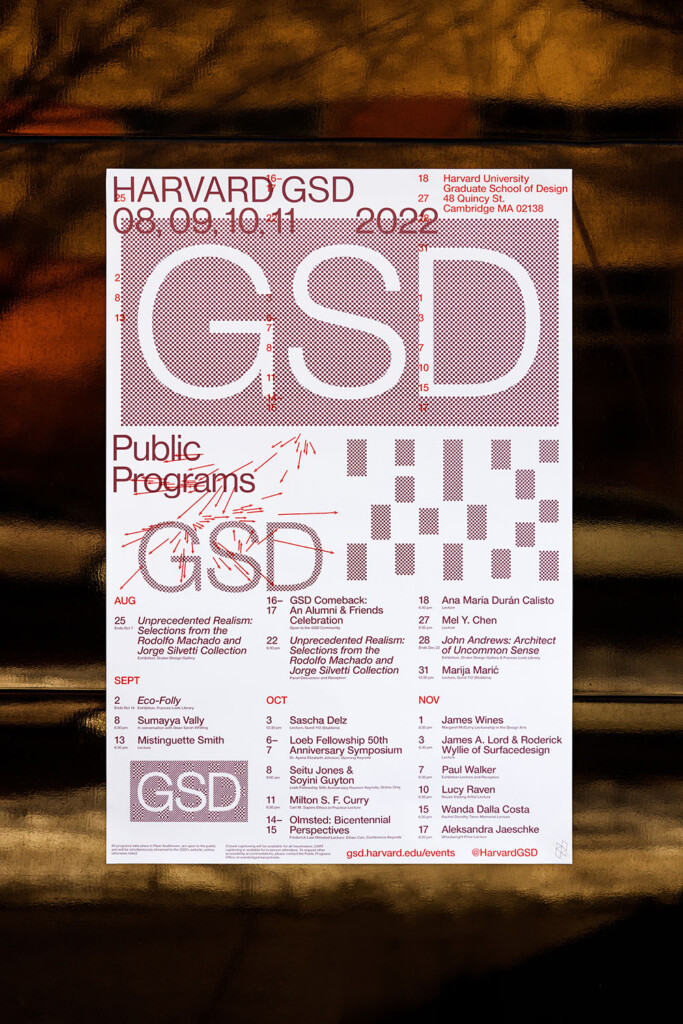

Within the work of graphic designer Ryan Gerald Nelson there is a persistent thread of experimentation. He experiments with images, typography, materials, and printing techniques, often manipulating all these elements at once. The compelling results range from the elegant and spare exhibition catalogue for Merce Cunningham CO:MM:ON TI:ME to the aggressive, overloaded posters he created for the Walker Art Center and Yale University. The attention to both big ideas and small details made his Studio Xee a perfect fit for designing the posters and related materials for the Fall 2022–Spring 2023 public programs at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). As we look back on the academic year, Chad Kloepfer, art director of the GSD, caught up with Ryan. The two met years ago when Ryan was a design fellow at the Walker.

Chad Kloepfer: We began discussing the past year’s public programs identity on a conceptual level, looking at how the project’s intellectual foundations could inform the design. Paige Johnston, associate director of public programs at the GSD, brought up The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (2013), a collection of essays by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney that draw on a radical Black intellectual tradition to critique academia. Moten and Harney write about ways to create the worlds you want to inhabit, outside of or adjacent to the existing world and its systems of knowledge. These are not easy concepts to formalize into a poster, but I wonder how, or if, Moten and Harney’s text ultimately fed into the final design?

Ryan Gerald Nelson: I did have some early moments of feeling a bit lost in all the potential ways and paths of interpreting The Undercommons and trying to land on certain ideas that I felt could propel my design decisions within the poster.

But as I dove deeper into the text I couldn’t help but notice the extent to which Moten and Harney’s observations and discourse feel so relevant to so many different spaces and aspects of society. A public programs and lecture series at a major university certainly felt to me like one of those spaces.

Ultimately, I felt like there was so much to glean from The Undercommons, and certain ideas from the book led me down a path that I wouldn’t have otherwise taken. As a graphic designer, that is something I always hope for in a project—some combination of collaborators, content, and reference material that expands my ways of thinking and making.

But to give some detail of how The Undercommons influenced certain design decisions of mine, we can look at how the authors define the idea of study. As Jack Halberstram observes in his introduction, Moten and Harney suggest that study is “a mode of thinking with others separate from the thinking that the institution requires of you.” Moten goes on to say that “It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice.”

I love this definition, and it’s clear to see how study is pervasive and already happening, and that we’re building a world through the acts of sharing space and ideas with one another (which is certainly something that the public programs and lectures at Harvard GSD become vectors for). So there’s an energy and potential in these notions that I attempted to capture within the poster through a sort of graphic/typographic density, overlap, and cross-pollination. The idea of study can be broad, but it prompted me to think about how I could use the design to reflect a sense of movement, momentum, a gathering of a chorus, a decentering, a deconstruction.

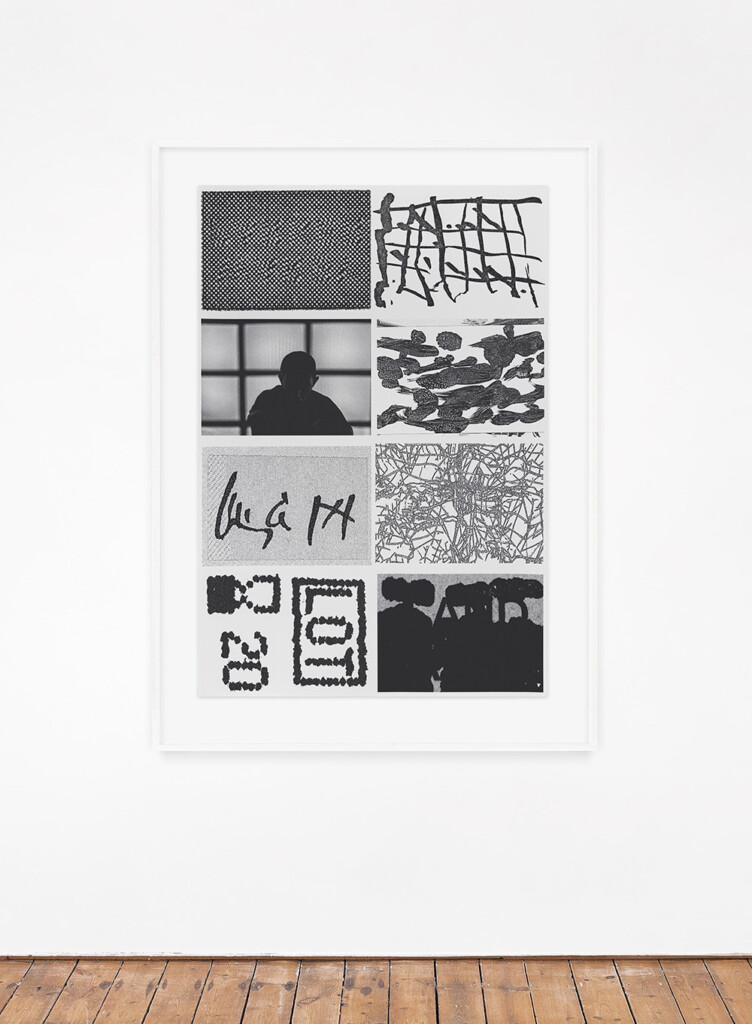

Something that attracted me to your work is that you are not exclusively a graphic designer. You also have a visual arts practice that runs parallel to your design practice. From the outside I can make formal connections between the two but I’m curious what the relationship of these worlds is for you?

These days the relationship is more separate than it has been in the past. Or at least in my conscious mind I’m always “switching” between the two: graphic designer mind and artist mind. Maybe that’s because these two worlds still, to this day, seem like oil and water.

silkscreen print on archival paper, 30 × 44 in.

But if I start to examine things more closely, I can see a relationship between certain approaches or aesthetic sensibilities that I have in both my art practice and my graphic design practice. Like gravitating toward a certain formal starkness or austerity, or a level of high contrast (tonally, typographically, relationally between forms and elements), or even just a very granular level of detail.

The use of images is crucial to your work—both as a designer and visual artist—and you have specific ways that you use and manipulate them. We don’t have artworks or photographs in our poster, but you have almost treated “GSD” as an image and manipulated its presence in multiple cases. Can you talk about using images beyond their representational value?

I definitely seek out more formal and aesthetic ways to use images, or as elements that feel or act as texture or tone. Or maybe it’s just a desire to use them less conservatively. Having worked mostly in and around the world of contemporary art I’ve often bumped up against the preciousness or strictness that surrounds images. Rules like: no cropping, no altering, no going across a gutter, etc. I understand it of course, but it does make me want to rebel against those rules when the opportunity arises.

I’m also a big proponent of using type as image or type as texture. There’s a very type-centric or type-first mentality that’s pretty firmly embedded in the way I approach design, which definitely pushes me to be more inventive with type and to find certain type moves that can do some of the heavy lifting in terms of conveying ideas and content. That said, I’m often aiming to create typographic moments that feel very integrated (i.e., not just floating or slapped on top), and weighty, and iconic.

Repetition plays a large role in the posters, emails, and related materials for this year’s public programs. How did this come about as a visual device?

I started using repetition throughout the visual identity as a simple strategy to reference space, scale, and expansion, which of course felt very appropriate for a graduate school revolving around architecture and urban planning.

Repetition as a visual device most noticeably plays out within the poster where there are three relatively prominent “GSD” graphics that are descending in scale from top to bottom. I repeated the GSD “tag” not only to establish these different spaces or levels, but also to represent two ideas at the same time: the idea of ascension representing expansion or growth on the one hand, versus the idea of descension representing a zooming or zeroing in on the other.

The vertically stacked grid spaces on the poster also nest with or mirror this structure. Whereas the three “GSD” graphics are descending in scale from top to bottom, the vertically stacked grid spaces are ascending in their column structure from top to bottom starting with the one big “block” column on top, then the two “block” zones in the middle creating two columns, and finally the three columns of listings on the bottom of the poster.

The day numbers from the calendar are also repeated and overprinted on the top half of the poster. The core parts of the poster were already locked in this nesting, symbiotic structure, so I wanted to bring in a similar, connective gesture to reinforce the repetition. In this instance I felt that the overprinting red day numbers become more of a representation of time as a space, presence, or structure.

You have a wonderful sense for type and typeface choices. Even the simplest typeface, in the right hands, can be used to great effect. How do you go about choosing a typeface (our poster is set in Helvetica Neue) and then using it?

I love a simple typeface! To me there are some absolute classics that I would probably be happy to use forever. I feel fortunate that when I was first being introduced to typography that my instructors were showing me the work of a lot of amazing Dutch graphic designers. That had a major influence on me, and I definitely noticed the typefaces they used, the sort of calculated unfussy-ness of their approach to type, and even their loyalty to using just a handful of typefaces for all their projects, or even a single typeface.

Just some of the typefaces I’m thinking of are: Gothic LT 13, Grotesque MT, Univers LT, Akzidenz Grotesk, condensed cuts of Franklin Gothic, more obscure cuts of Times New Roman like MT or Eighteen, Gothic 720 BT, Pica 10 Pitch, Prestige Elite, AG Schoolbook, and of course Helvetica Neue, among many others.

As far as choosing a typeface goes, I like to keep that process simple as well. I think the width of the strokes are a major factor. Sometimes I’m trying to find stroke widths that feel in harmony with other elements like images, content, format, the proportions of the format, etc. But in other instances, it makes more sense for the stroke widths to have a lot of contrast or weight difference in comparison to the other elements. Lastly, I think the letters used in the main title of the design project play a big role in how I make my typeface selections.

With the uppercase letters in “HARVARD GSD”, I’m primarily looking at the “R” and the “G”: both great letterforms that I happen to find pretty irresistible when they’re typeset in Helvetica Neue. With a Helvetica Neue “R”, it’s the curve of the leg. It’s a super elegant curve with a slight outward taper down on the baseline that I think sets Helvetica Neue apart. With the Helvetica Neue “G”, it’s almost all about that downward spur in the bottom-right of the letterform that’s perfectly balanced and gives the “G” such an iconic stance.

Had the main title of this project not included an “R” and a “G”, I’m sure I would’ve chosen a different typeface. It all comes back to content and what you’re working with—even down to the letters being used.

I don’t imagine you have a traditional studio structure as a designer, but the desk-job portion of running a studio is not something they teach in school. Is there any kind of learning curve when it comes to practicing design for clients and what it takes to “manage” a studio?

I think there can be a fairly steep learning curve considering that being an independent or small studio graphic designer can often require you to possess so many graphic design adjacent skills. You might only be working on actual graphic design for 20 percent of the time during a project, while the other 80% of the time is dedicated to aspects like pre-production, editing content, communicating with collaborators and vendors, ensuring quality final production, etc. Like you mention, design schools barely and sometimes never teach these aspects of graphic design to students, but they’re obviously important.

These types of skills tend to live in the background which is probably why they go untaught in design schools and, frankly, are not even spoken about very often. But I wouldn’t trade them for anything simply because skills like these give me the confidence to handle just about any project thrown at me and allow me to focus more on the actual graphic design.

Why the Digital World Needs Sustainable Architecture: An Interview with Marina Otero