Ehao Wu Wins APA Economic Development Division Holzheimer Memorial Student Scholarship

First-year DDes student Ehao Wu has won the 2025 Holzheimer Memorial Student Scholarship for Economic Development Planning , awarded annually by the American Planning Association (APA), for his paper “Innovation Districts and Urban Economic Resilience: Kendall Square’s Sectoral Transformation,” written for Rachel Meltzer’s class, “Local Economic Development: Turning Theory into Practice.”

Named in memory of economic development visionary Dr. Terry Holzheimer, the scholarship includes a $500 award and will be presented at the APA National Planning Conference in Denver, Colorado, in late March. Wu’s paper will be published on the Economic Development Division (EDD) website and distributed electronically to EDD members in the News & Views newsletter.

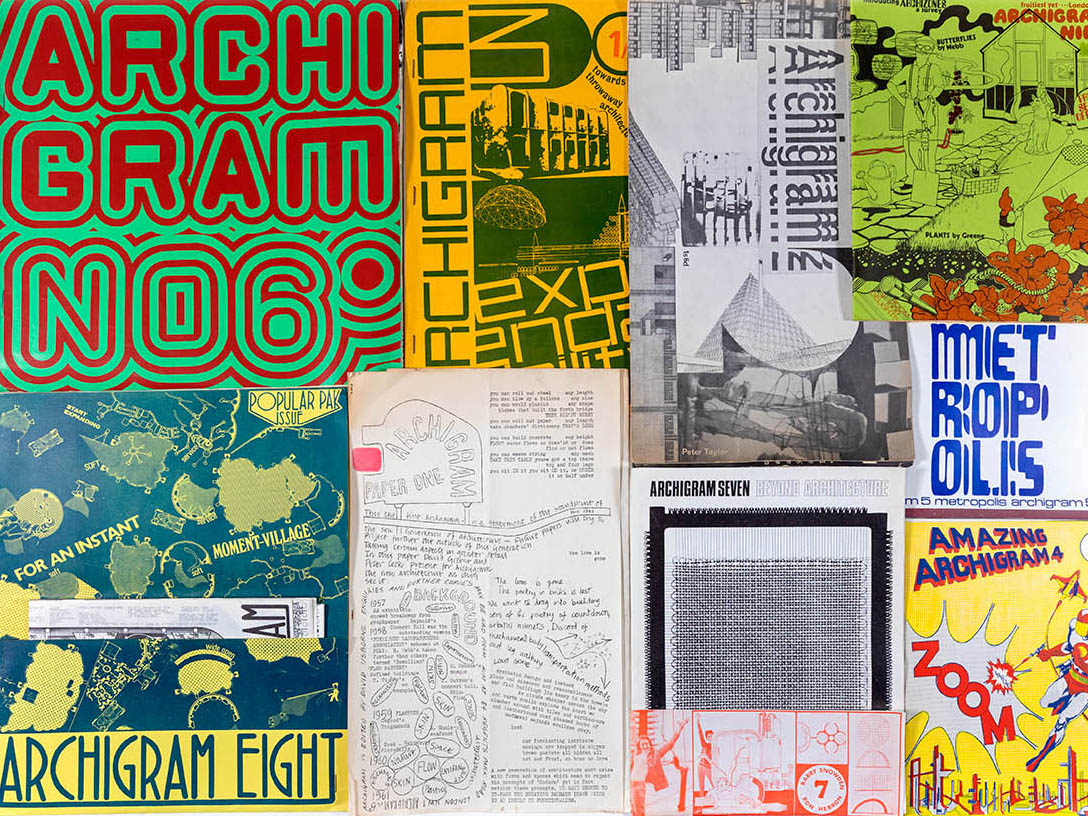

A New Way to Explore Archigram, a Rarity in the Frances Loeb Library

The iconic experimental magazine, Archigram , is about to make its return to contemporary culture with a forthcoming facsimile boxed edition of all 9½ original issues, nine of which can be found in the Frances Loeb Library at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).

The facsimile edition, edited and featuring essays by Peter Cook, one of the original founders and 2015 Kenzō Tange Visiting Professor at the GSD, along with essays by David Grahame Shane and Reyner Banham, promises to “faithfully reproduce” the elements that made the magazine such a joy to read: “flyers, pockets, a pop-up centerfold, posters, gatefolds, and an electronic resistor.” Publisher artbook also notes that ths edition includes some new material: a glossary index, a “scrapbook of previously unseen archival images,” and bibliographies.

Archigram was first published in 1961 after Peter Cook, David Greene, Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, Ron Herron, and Mike Webb gathered to form a collective that challenged mainstream design trends towards modernism. Together, for nearly a decade, they created speculative designs, exhibits, and writing, along with Archigram. The final half issue (a single page) was published in 1974.

Drawing from early twentieth century groups such as the Dadaists who distributed handmade packets that would one day be known as “zines,” the Archigram collective used collage, woodcut prints, and stapled pages, photocopying early issues for distribution and creating more complex design elements that mirrored the era’s new technologies, consumerism, and Pop Art. Together, the group developed a new vision for architecture that centered avant-garde aesthetics, with its futuristic designs and sense of play.

One of their most famous magazine issues featured Ron Herron’s “Walking City”—building units set on moveable legs that, like scurrying beetles, allow dwellers to move to necessary resources and communities. The “Zoom” issue helped the group find a broader audience, writes GSD archivist Ines Zalduendo , when Reyner Banham brought six copies from England to the US, where it landed a spot in Architectural Record. “It is easy to see how this issue,” Zalduendo notes in the archive’s collection record, “which took inspiration from Roy Lichtenstein and sci-fi comics, successfully conveyed the group’s characteristic rallying against high modernist culture.”

Zalduendo acquired the extremely rare Archigram collection—one of only three in the world—in 2019 for the GSD archives, where visitors can experience the zine firsthand. Also included in the collection are ephemera from the group, such as greeting cards, a hand-colored print of “Block City,” flyers, and posters.

In December 2024, Cook published a tenth issue of the magazine, available online, with contributors including Marjan Colletti and Klein Dytham, among others. For those who want to build their own Archigram archive, the forthcoming facsimile edition offers consumers the same tactile delights as the originals—along with the nostalgia of the group’s 1960s and ’70s radical design sensibilities that changed the course of architecture.

When the Client is a Nation

Inside the Peabody Museum on a windy October day, leaders of the Sac and Fox Nation peered into the eyes of their ancestor, William Jones , the second Indigenous person to graduate from Harvard, in 1901. Posed in a cap and gown, Jones’s black-and-white photographs sit under a glass case beside a pair of beaded moccasins.

“He’s almost as good-looking as I am,” Principal Chief Randle Carter joked with Robert Williamson. Carter and Williamson had traveled to Harvard from Oklahoma, where Jones was born in 1871 and the tribe is based today.

The Sac and Fox are one of 574 Native tribes who operate as nations within a nation; they have the right to self-governance and maintain their own political systems . Williamson and Carter were invited to Harvard by Eric Henson, a lecturer in Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a longstanding member of the Harvard Project on Indigenous Governance and Development , which helps Indigenous nations worldwide strengthen their governance systems. Henson’s Fall 2024 GSD course, “Native Nations and Contemporary Land Use”, brought together GSD students with representatives of the Sac and Fox—along with the tribe’s collaborator, a professional hockey team—to help the tribes meet their goals to regain sovereignty over their ancestral lands in Illinois.

“With a focus on land use, landback initiatives, and economic development opportunities,” writes Henson, “the course provides in-depth, hands-on exposure to how Native people are addressing these issues today.” Landback initiatives have been underway since the colonial era but only became widely known as such in the last few years. Part of Native nations’ work towards claiming their sovereignty, landback focuses on a number of initiatives, including acquiring land that was stolen from them throughout the process of colonization.

“If you’re building something new, or designing a park,” said Henson, explaining the importance of learning Indigenous history at a design school, “you have these steps you are supposed to check off: Did we do this review? Did we look for artifacts or archaeological dig sites? I’d like to see a degree of understanding beyond that. It’s not just a box to check off. You’re talking about real people who are victims of genocide and war and outright theft of their traditional territory. Taking a few minutes talking to a tribal leader before starting a design might open your eyes to the place in which you’re doing that work.”

For example, he says, in Bendigo, a town north of Melbourne, Australia, town leaders collaborated with the Dja Dja Wurrung , the Indigenous community, to incorporate Native design elements, revitalizing the town and attracting more investors. Henson noted that there are Native design elements in many buildings in Bendigo, which offers a model for others to follow.

This semester, students are working with two Indigenous Nations. Henson, a Chickasaw citizen, draws from his deep contacts with tribes around the US who have requested to work with him and his classes. The course Henson teaches at the Kennedy School , Nation Building II/Native Americans in the Twenty-First Century, offers collaborations with Indigenous Nations and now serves as a companion to the course at the GSD, with projects carrying over from one to the other. The course at the Kennedy School is cross-listed with the GSD, the Faculty of Arts and Science, the Graduate School of Education, and the Chan School of Public Health.

“With more education around Indigenous history, culture, and design, there could be tremendous collaboration between designers and Indigenous nations,” Henson argued, “with Indigenous design elements incorporated. In addition, non-Native communities that neighbor tribal lands have great opportunities, if they want to embrace them and work with tribes.” Not least of which, Henson explained, is the tribes’ access to federal funding and their role as major employers, particularly in rural areas.

This mutually beneficial relationship is what Rahul Mehrotra hoped for when he suggested a Native-focused GSD course to Henson in 2020, when Mehrotra was chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design. Henson collaborated with Philip DeLoria and Daniel D’Oca to design an interdisciplinary GSD class they called “Land Loss, Reclamation, and Stewardship.”

“In the context of discussions at the GSD on diverse ways of understanding history, and in the context of climate change,” said Mehrotra, “learning from traditional practices is very important. The relationship that Native Americans have to the land, and to nature more broadly, is sensitive, beautiful, poetic, and empathetic—and incredibly intelligent.”

GSD students’ work impacts the lived environment around the world, Mehrotra explained, and with more education about Indigenous people and their history, design students’ sensibilities would invariably shift.

“I wanted the Indigenous studies course to have history, design, and practice components,” said Mehrotra, “so that students would have a sense of what they can learn from history and traditional practices as they intersect with design.”

This past fall in Henson’s course, GSD students Cayden Abu-Arja (MArch I / MUP ’27) and Neady Oduor (MDes ’26) opted to work with Carter and Williamson to design a program to help them regain their ancestral lands, which the tribe determined was one of their primary goals.

“Our traditional lands,” Williamson explained, “are not in Oklahoma.”

For 12,000 years, the two tribes, then known as Sauk (now Sac), the Yellow Earth People, and Meswaki (Fox), the Red Earth People inhabited the area around Quebec, Montreal, and eastern New York state, but were forced southwest by the Iroquois, and then further west by the French. The two tribes banded together and moved to Illinois, establishing their summer village in Saukenuk, today known as Rock Island, along the Mississippi River. There, they planted 800 acres of corn, vegetables, and fruit to feed the almost 5,000 people in the well-organized community.

Abu-Arja and Oduor quoted tribal leader Black Hawk’s autobiography, in which he describes his memories of that place: “It was our garden (like the white people have near their big villages) which supplied us with strawberries, gooseberries, plums, apples, and nuts of different kinds, and its waters supplied us with fine fish, being situated in the rapids of the river.” Black Hawk recalled spending his childhood summers on the island, surounded by family.

In 1804, colonists tricked the Sac and Fox chief into signing a treaty that gave the land to Illinois, forcing the tribe off their summer grounds to the west of the Mississippi. By 1832, with the Sac and Fox people starving, Black Hawk led the community back to Saukenuk to plant their traditional summer crops.

“After years of encroachments from the US government,” said Williamson, “this was Black Hawk saying, ‘I want to go home.’” Instead, said Williamson, the Illinois militia “slaughtered women, children, and older men” over the course of more than three months, in what colonists called the Black Hawk War. The Sac and Fox were subsequently pushed further west again, this time to Oklahoma, where they live today and continue to fight for access to their ancestral lands.

Landback Initiatives & Innovative Collaborations

At the beginning of January, another tribe, the Prairie Band Potawatomi , were approved by the Illinois State House to receive a land transfer of 1,400 acres, which makes up Shabbona Lake State Park, named for Chief Shab-eh-nay. The government sold the land illegally in 1849, violating a treaty the Prairie Band had signed 20 years earlier. The Potawatomi have agreed to continue allowing public access to the park, which will be maintained by the state.

Tribes across the US have undertaken landback initiatives in different ways, from acquiring the land through private purchase to lobbying for it from state lands or through estate planning. For the Sac and Fox, a Nation with about 4,000 members, the goal is to follow the lead of the Potawatomi to reestablish their footing back in Illinois around the site of Saukenuk village. Today, Illinois maintains Black Hawk Historic Site on the tribe’s ancestral lands, with a statue of the warrior, a small museum that describes Saukenuk, and a 100-acre nature preserve. Williamson noted that, like many other Indigenous US tribes, their leaders’ names have been used for streets, towns, professional sports teams, and even army helicopters. They deserve to have access to their ancestral lands.

Joining Carter and Williamson on their trip to Illinois were representatives from the Blackhawks Hockey team, whose CEO, Danny Wirtz, has invited the nation to collaborate in ways the Sac and Fox choose. While many Indigenous advocates have argued for professional sports teams to change their name, Wirtz suggests that the collaborative work he and his team are doing with the Sac and Fox requires more authentically engaging with one another. The tribe voted to work with the hockey team and is prioritizing economic development, strategic planning (including landback initiatives), and language preservation projects.

“Our partnership with Black Hawks’ tribe, the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma,” says Sara Guderyahn, the Chicago Blackhawk’s Executive Director, “is centered around education and cultural preservation with the goal of supporting the Nation’s priorities for sovereignty. To that end, we are excited and optimistic that this project is an important step to explore opportunities for the Nation to reconnect with their original homelands in Illinois.”

GSD students Abu-Arja and Oduor began their work with the Sac and Fox by learning about the tribe’s history, including their forced migration through the US, Black Hawk’s leadership, and the Nation’s ancestral lands. The group’s visit to the Peabody Museum with Carter and Williamson highlighted the Sac and Fox’s most famous members: anthropologist William Jones, whose photos and writings they viewed alongside the leaders at the museum and in the archives, and football player Jim Thorpe, who won two Olympic gold medals in 1912.

“When you look at the record books,” said Chief Carter, “Thorpe was not a citizen of the US. Before 1924, Indian people were not citizens of the United States. The record should say he was a citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation.”

Henson led the group to visit a site on Harvard’s campus that brings Thorpe’s legacy back to contemporary material culture. At what’s now Clover Food Lab , the ceiling tiles that depict the early twentieth-century Harvard football league pennant flags include the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. When Jim Thorpe led Carlisle to defeat Harvard in 1911, the Indian School was cut from the league; Harvard never played them again. The Indian Industrial school was part of the US government’s attempt to erase Indigenous culture through the forced removal of thousands of children from their homes and families, under the motto “kill the Indian, save the Man.” When the tiles were uncovered on Massachusetts Avenue, right across from Harvard’s gates, in a 2016 renovation , they restored to the record in Cambridge the story of Jim Thorpe at Carlisle, before he went on to win Olympic gold medals.

The group’s visit to the site was part of a tour Henson led, which was originally designed by Jordan Clark, Executive Director of the Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP) and a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah. The tour makes visible the Indigenous histories that are often missed all around us.

For example, Henson pointed out a plaque on the side of Matthews Hall, commemorating the history of Harvard’s Indian College— founded by missionaries in the 1640s—whose bricks were eventually dismantled to build other Harvard structures. Henson pointed to a spot on the lawn beside Matthews Hall, where a 1990s archeological dig revealed pieces of the press used to print the Eliot Bible, written in Algonquin (a language of Indigenous tribes), the first Bible printed in the US, now held at the Houghton Library . Henson noted the plaque on the president’s house that names the enslaved people who labored there, and the rusty pump in the center of the yard, which marks the water source from which Massachusett and other Indigenous people were cut off when settlers claimed the site.

Making Indigenous histories visible, highlighting how their stories predate colonization by thousands of years, as well as how they are irrevocably intertwined with Harvard’s history, helps to make tangible the ethos of the land acknowledgment that the GSD wrote in collaboration with HUNAP and reads at the beginning of every public event.

Strategies to Educate the Public and Regain Access to Saukenuk

After learning the histories of Indigenous nations in the east and midwest, Abu-Arja and Oduor focused on designing a program centered on “co-management” of the Black Hawk State Historic Site, which they say the Sac and Fox Nation “sees…as a way to connect with their ancestral homeland…and pass on traditions (some of which were lost when they were removed from their land).” The team outlined three goals: 1) creating storytelling opportunities so that people understand the “social and cultural significance of the Black Hawk State Historic Site” to the Sac and Fox Nation, 2) developing revenue streams, and 3) increasing collaboration with Illinois state.

They defined 15 different activities, from collaborating with the Sac and Fox to develop new exhibits at the existing historic site museum, to building clan houses for cultural activities, hosting riverside storytelling sessions and ceremonies, creating a gift shop, and “tailoring [the tribe’s existing language programs] to young students who visit the site.” They note that the Nation can turn to existing protections, for example, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which would support co-managing the cemetery where Black Hawk’s children are buried but remain unnamed on signage that commemorates settlers. As precedent for managing burial grounds, they cite Minnesota’s Indian Mounds Regional Park, which was developed around the gravesites of several tribal nations to protect the mounds and share their people’s histories. By increasing the public’s knowledge of and engagement with the Sac and Fox Nation, as well as collaborating with the state government, the Sac and Fox’s case for landback will become more visible—and therefore, more viable.

At the end of the semester, Abu-Arja and Oduor presented their proposals to the Sac and Fox Nation, who are moving ahead with their plans to develop the programs in Illinois, which they hope will bring them one step closer in their two-hundred-year battle, starting with their ancestor Black Hawk, to regain their lands.

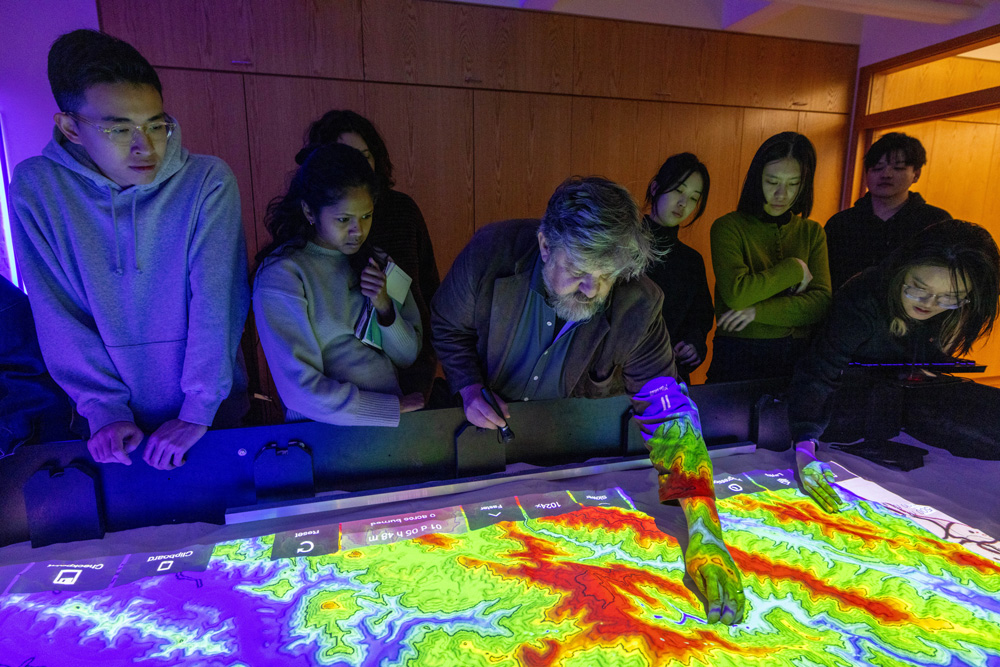

Landscape Architecture Students Explore Pioneering Climate Visualization Techniques to Inform Design

Droughts, floods, food shortages, species extinction—the impacts of climate change are physically tangible. Yet, the terms and data used to describe these predicted impacts often seem abstract. Richer visualization techniques offer great promise to communicate the consequences of climate change and thereby promote the adoption of strategies to preempt these effects. This semester at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), master of landscape architecture (MLA) students are exploring two such innovative modeling approaches: a framework for understanding spatial impacts of climate strategies over time, and a modern sand table that supports real-time simulations.

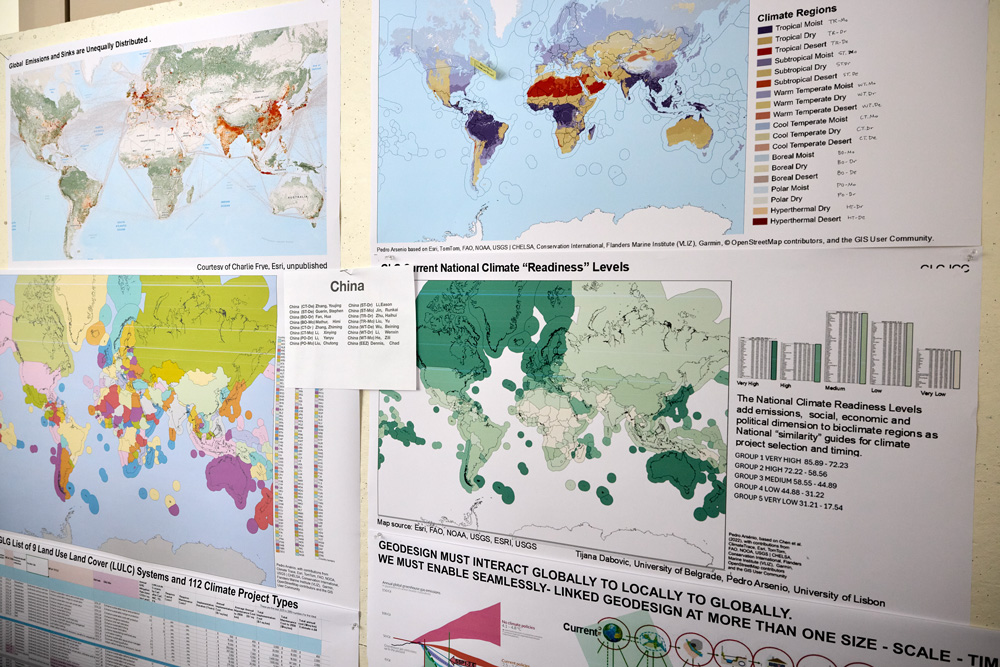

Since the 1960s, Carl Steinitz—Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning Emeritus—has been contemplating land-use change as a designed process. As part of the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis, Steinitz began using geographical information system (GIS) maps to evaluate the impacts on a given area of variables such as population growth and migration, financial influx, and environmental conservation. In the ensuing years, Steinitz developed a framework for “geodesign,” a term coined to describe design in a space linked to a geographic coordinate system with its accompanying specificities. Today the International Geodesign Collaboration (IGC), which Steinitz helped found, defines geodesign as “a collaborative approach [that] uses GIS-based analytic and design tools to explore alternative future scenarios in response to global problems.” When first exploring this problem five decades ago, Steinitz initiated his geodesign work with a two-square-mile geographical region; recently, he expanded this scope to the global scale.

In 2022, in conjunction with the company Esri —a global leader in GIS software, location intelligence, and digital mapping, cofounded by Jack Dangermond (MLA ’69)—Steinitz and additional collaborators began work on the ICG Global to Local to Global (GLG) Climate Mitigation Project, building the technology to facilitate geodesign for the purpose of climate change mitigation.1 Steinitz introduced the project to MLA Core IV students (those engaged in their final studio of the core sequence), characterizing mitigation as “a multi-jurisdiction, multi-scalar geodesign problem. Climate change,” he explained, “is a global existential phenomenon, and all nations must act in collaboration if climate mitigation is to succeed. Guided by climate science, this requires looking and thinking ahead in time, globally to locally to globally, and planning now to act now for the future of everyone.”

While multinational agreement and a global oversight of planning, negotiation, and implementation does not yet exist, Steinitz and colleagues view the GLG Climate Mitigation Project, a protocol to facilitate this process, as necessary infrastructure for future climate action. Building from a geodesign framework published in 2012, Steinitz has created tools to identify mitigation strategies to optimize impact by considering the date of initiation (for example, 2025, 2050, or 2080), execution and maintenance costs, alterations in climate (temperature and aridity), and additional variables across a span of decades. Focusing on changes in land use, the goal is to lower carbon emissions below zero, ideally (if perhaps improbably) returning atmospheric measurements to pre-Industrial Revolution levels. In short, the GLG Climate Mitigation Project offers a preview of, and guidance on how, mitigation-related decisions can affect our future.

Following his explanation of the project, Steinitz walked the MLA Core IV students through a tutorial on how to use it. This exercise served a double purpose, providing a test run for the tools themselves while preparing students for their upcoming semester-long studio “The Near Future City,” focused on Boston’s Charlestown neighborhood. Lorena Bello Gómez, GSD design critic in landscape architecture and lead instructor of the studio, sees the GLG Climate Mitigation Project as a climate action framework students can use to determine suitable mitigation strategies for the studio’s site. These include strategies such as enhanced wetland restoration, neighborhood energy retrofits, infrastructural recalibration, urban canopy growth, and sustainable wastewater management.

Charlestown sits within a warming climatic region that, in years to come, will face increasing challenges around already-problematic issues of inland flooding, salt-water inundation, and heat island effect. Highlighting why climatic shifts matter, Steinitz asked students about appropriate trees to plant at this location today. “Where are you going to look [for precedents]—Charlestown or South Carolina?” Considering that the latter approximates Charlestown’s expected climatic region in 2050, “I’d look to South Carolina if I were you,” Steinitz declared, “especially if the trees take thirty years to grow,” as many species do. This point, while seemingly simple, underscores an important reality: today’s designs must take future conditions and long-term repercussions into account.

For the students, then, the GLG Climate Mitigation Project offers mitigation strategies for Boston’s climatic region that can be adapted for maximum impact in Charlestown. Once students have a particular strategy in mind, they can explore a different visualization technique—the Simtable . Invented by Stephen Guerin, affiliated with Harvard’s Visualization Research and Teaching Laboratory , the Simtable is a high-tech sand table that uses GIS data and computational modeling to explore complex phenomena, such as wildfires or chemical plumes, that involve people, places, and things interacting over time.

To demonstrate the Simtable’s interactive and projective capabilities, Guerin projected a topographic map of a fire-threatened Los Angeles region onto the sand. He asked the students to shape the sand by hand, following the map’s contours, building mountains and excavating valleys. Onto this modeled surface Guerin then projected satellite imagery of the area. Setting parameters such as time and weather conditions, he began testing scenarios for the fire’s progression and containment, using a laser pointer to select and implement different tactics. For example, how does bulldozing a trench from point A to point B impact the fire’s spread? What about sending resources to points C and D simultaneously? Or staggering them, while designating certain routes for human evacuation? The interactive simulations offer immediate feedback with minimal effort, facilitating a rapid iterative process for exploring, adjusting, and assessing interventions. Guerin’s ingenious tool has been employed numerous times during real-life emergencies, including the Los Angeles fires in January 2025.

For GSD landscape architecture faculty, the Simtable offers phenomenal possibilities to inform design. Bello envisions the table as a tool that could allow architects to “move back and forth between design and performance, exploring parameters in a more fluid iterative process” than afforded by conventional physical modeling techniques, which are notoriously labor and time intensive. Furthermore, Simtable’s interactive nature could enhance community participation in climate adaptation and mitigation planning, the success of which often relies on robust social engagement. As Bello notes, instead of showing data on a stationary screen, “you are projecting data onto [a tangible representation of] the territory, empowering people to construct that territory, which empathetically puts them in mind to act.”

Yet, before the Simtable can be employed by architects, experimentation is required. “We need to translate this tool into our field,” Bello says. “How might we use the Simtable, and how can it be used in landscape design? That is what we want to test.” And this is where the MLA Core IV students enter the picture. Just as the students tested Steinitz and team’s tools, Core IV faculty will continue to work with Guerin this semester to introduce the Simtable in early stages of architectural investigations, from site selection through design performance.

Of course, visualizing data is only part of the work undertaken by designers. Each site comes with its own history and current residents, who have with their own aspirations. Thus, in preparation for the Core IV studio, the students met with several people with strong ties to Charlestown. In addition to Steinitz’s and Guerin’s workshops, MLA students heard from experts such as Alex Krieger (GSD professor in practice of urban design, emeritus), who shared insights about Charlestown’s physical evolution; officials from the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, and other institutions, who discussed current plans for the neighborhood; and nonprofit leaders from organizations such as Boston Harbor Now, who work to address community needs. Students must consider all thisinformation and more as they assess and design for their urban site. The innovative methodologies embodied by the GLG Climate Mitigate Project and the Simtable will further support the students’ design efforts, now and in a future marked by inevitable change and environmental crisis.

- GLG Climate Mitigation Project collaborators include Stephen Ervin (Harvard GSD), Pedro Aresino (University of Lisbon), Tijana Dabović (University of Belgrade), Michele Campagna (University of Calgary), and Alex Killing (Yale Center for Biodiversity) among others. ↩︎

Five Lessons from the Gund Hall Renovation

In late May 2024, following commencement at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), the initial stage of Gund Hall’s multiphase renovation began. Designed by GSD alumnus John Andrews (MArch ’58), Gund Hall first opened in 1972, uniting the school’s three departments under one roof. Andrews’s scheme foregrounded the school’s pedagogical philosophy, apparent in the building’s shared studio block, which featured extensive glazing and 125-foot clear-span steel trusses. Described by reviewers as “visually dramatic ” and “a handsome structure ,” Gund Hall was received within the architectural community as a bold achievement.

The recent renovation, intended to make the building more climate friendly and comfortable for occupants, is equally bold, balancing the twin goals of conservation and innovation. Aside from serving as a paradigm for the preservation and revitalization of mid-twentieth-century modern architecture, the Gund Hall renovation offers valuable takeaways for clients and project teams. These five lessons suggest that, when introduced at the project’s earliest stages, collaborative decision-making sets a strong foundation for success.

1. Designate clear priorities

Many aspects of Gund Hall, designed and constructed more than a half-century ago, required attention. The question was, where to begin within this nearly 165,000 square-foot building? To help determine the priorities for the multiphase renovation, the GSD turned to Bruner/Cott Architects, who performed a comprehensive feasibility study. It revealed that the studio block (known as “the trays”) consumed energy at a rate double that of the rest of the building, due largely to heat loss and solar heat gain through the single-pane-glass curtain walls and clerestory windows. And not only were the trays energy inefficient, they were also notoriously uncomfortable in terms of temperature extremes and poor lighting conditions. (As one alumnus noted, “I spent a very cold winter in 1996 at my desk drawing with mittens on, and I don’t think I’m the only one who has done this.”) In addition, the trays’ terraces were not wheelchair accessible. Thus, for the initial phase of the renovation, the GSD identified the trays as the area that would deliver the highest impact on operational carbon and the students’ daily experience.

While it is too soon to quantify reduced energy usage following the renovation’s first phase, anecdotal reports suggest that, since the project’s completion, studio temperatures have been far more comfortable during both hot and cold weather. Students and faculty also applaud the improved quality of daylight and the lack of glare. Sarah Whiting, dean and Jose Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture, noted that the renovation has transformed not only the temperature in the trays but also the light. “The feel of the trays is completely different,” she said, “and it’s extraordinary.”

Another example of prioritization involved ensuring efficiency, specifically in preparing for and executing construction. To confine intensive construction to 12 weeks, the GSD opted to move summer classes online, which provided Shawmut Design and Construction’s workers unfettered access to the trays. And throughout construction, a tower crane located in front of Gund Hall—while inconvenient for visitors to the building—allowed work to proceed smoothly and on schedule. According to Shawmut senior project manager Glenn Patrick Ryan, the crane proved indispensable in safely transporting unwieldly materials to and from the roof. “I don’t think we could have achieved the needed efficiency had we not planned to have the crane in place to support the workers,” noted Ryan. Determined early on, “this piece of our logistics plan was critical.”

2. Consider Design Assist project delivery

As opposed to the standard project delivery method used throughout the twentieth century—where design professionals create the design and then pass it to the construction team to build—with Design Assist (DA), the designers, construction team, and subcontractors work together throughout the design phase. This process increases collaboration and innovation while minimizing risk, leading to DA’s growing popularity in recent years. In the estimation of Ben Szalewicz, chief of GSD Facilities and Campus Operations, the early partnership with Bruner/Cott, Shawmut, and other consultants allowed the team to address—if not entirely circumvent—critical issues that arose during construction. This was no small feat, considering the project’s complexity, which included uniting a new, high-tech glazing system with a 50-year-old steel structure. “The benefit of Design Assist,” said Szalewicz, “was that we were able to accomplish this project with relatively few hiccups in a really short time frame. I don’t think we could have done this had we not partnered early on with this whole team.”

For the Gund renovation, DA’s value went beyond simply adhering to the project’s strict timing. Rather, as GSD lecturer in architecture and chair of the Building Committee David Fixler explained, the process allowed the team to “maximize efficiency, performance, aesthetics, and peace of mind.” During the design process, the team collaborated with A&A Window Products, who leveraged their manufacturing relationships to devise a high-performing glazing system that, despite the use of triple-pane units, maintained the original single-pane-glass system’s low profile and narrow sightline. Preserving the original appearance and relative dimensions of the facade as designed by Andrews was a critical aspect of the project’s conservation aims. And as Ryan noted, early partnering for the project facilitated “tangibles [such as] the plan, the logistics, the schedule, the nuts and bolts. Yet the intangible benefit of the Design Assist process was the development of a team,” an immeasurable asset that played a huge role in bringing the renovation to fruition.

3. Learn from an in-situ mock-up

In the months before construction began, the project team built a three-bay mock-up in the southeast corner of the Pit, on the ground level of the studio block. The decision to build this mock-up in situ instead of freestanding, either in Gund Hall’s backyard or in a testing facility, proved essential to the renovation’s execution. Integrating the new glazing system with the existing steel proved challenging, and the mock-up provided troubleshooting experience alongside the opportunity to refine installation tolerances and techniques.

The trays’ 112 clerestory windows, one of which was included in the mock-up, offer a perfect example. “Each clerestory window is its own mini project,” Ryan explained, “requiring work by six different trades that had to come back at several different junctures. The first time we attempted this, we weren’t as efficient as we needed to be to do 111 more.” Through the mock-up, however, “we learned a lot about the building, the existing conditions, and how the new systems connect. We also learned a lot about ourselves and how to execute the project, especially given the tight time frame.” Multiplied by 111, those efficiencies were incredibly valuable for avoiding the unexpected and saving time during construction.

4. Think about the future

Aside from increasing energy performance and occupant comfort, another issue the renovation sought to address was future repairability. Consider the trays’ curtain walls. Andrews’s design used neoprene gaskets to secure the glass panes, which relied on the panes below them for support—an arrangement that made repairing broken elements extremely difficult. As project architect and Bruner/Cott associate George Gard (MAUD ’14) noted, for the renovation they designed a curtain-wall system in which each pane is individually supported “so, if a pane breaks, it’s a relatively straightforward process to take that glass out and put new glass in. Similarly, if there’s damage to the curtain wall itself, those pieces can be removed and replaced in a local manner.”

In addition to considering Gund Hall’s maintenance and longevity, the project team paid attention to the life cycles of the new elements they introduced. They reduced the project’s waste wherever possible, for instance by retaining most of the trays’ existing glazing support steel despite the complicated merger of old and new. They also adopted materials that were manufactured with recycled products, including roughly 90 percent of the aluminum used for the new curtain-wall system. In terms of embodied carbon, such strategies help minimize greenhouse gas emissions now and moving forward.

5. Remember that the payoff may not be visible or immediate

“In some ways, the project’s best parts are virtually invisible. And the more invisible they are, the better it is,” declared Fixler. As a delicate balance of innovation and conservation, much of the Gund Hall renovation is intentionally invisible to the eye—improving energy performance while retaining the originality of Andrews’s design. The building looks how Andrews intended, and this is precisely the point; in this sense, the project’s invisibility indicates success. This holds true for issues of sustainability in general, where the absence of waste and greenhouse gas emissions signifies achievement and is often measured over time.

Another facet of the Gund renovation involves concrete conservation, which Fixler described as “an art and a science [that depends on] the right aggregate, the right mix, the right conditions, and really skilled people to execute the work.” Far from invisible, the newly treated areas at first stand out, though care is taken with an extended curing process to give the sample mixes a cycle through the seasons prior to selecting the right match. Once applied, they will continue to age over years to approach the original concrete’s hue. Here too, then, the payoff is not immediate, yet it is eventually visible (ironically, by becoming invisible). The final concrete repairs will be performed later this year.

Of course, enhanced light quality, comfortable interior temperatures, and accessibility improvements were apparent to building occupants right away. Coupled with the renovation’s less immediate and invisible payoffs, these aspects will benefit the GSD community for years to come.

Neeraj Bhatia’s Studio Envisions California’s High-Speed Rail as an Armature for Care

This January, the day before the Los Angeles fires ignited, California Governor Gavin Newsom announced the newest phase of construction on the long-awaited California High-Speed Rail (CHSR) from San Francisco to Los Angeles, spanning the Central Valley. Neeraj Bhatia, a design critic in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, explored with his students how the CHSR will transform the state by giving rise to what he calls a “territorial city” that “spans vast swaths of land to include both urban and rural settlements.”

Bhatia asked his fall 2024 option studio, which was sponsored by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, to consider how vulnerable populations in the Central Valley could benefit from the CHSR. The new rail system, he says, offers “an armature for accessing dispersed populations that have been underserved.” In October, the studio visited the Central Valley, with support from the Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Critics have cited failures of the CHSR such as its high price tag and long timeline, but, once completed in 2050 (as projected by the Rail Authority), riders will be able to cover the 350 miles between Los Angeles and the Bay Area in under three hours; it takes more than six hours by car and nine by conventional train. The CHSR is intended to be competitive with air travel and to help improve the environment—as well as quality of life—with less motor traffic and congestion. It will also, inevitably, change the communities connected by the system, according to Bhatia, by allowing “people to experience different cultures through living in geographies they are less familiar with, and trying to reckon with those differences to find points of empathy.”

California’s coastal cities are characterized by “scenic landscape, progressive environmental movements, and density,” Bhatia writes, “while inland California is characterized by resource harvesting and extraction, conservative values, and a depravity in social infrastructure.” Residents in the urban hubs are facing the affordable housing crisis, and, as we’ve recently witnessed in Los Angeles, worsening natural disasters. Meanwhile, with oil reserves and some of the richest soil in the world, the Central Valley’s bounty of tomatoes, lemons, peaches, walnuts, and almonds—among hundreds of other fruits and vegetables—are harvested by 55,000 migrant workers who help feed the nation.

These “two Californias”—urban and rural, progressive and conservative, dense and sprawling—a “microcosm of the United States,” have remained distanced from one another, but the CHSR will collapse their proximity, which Bhatia argues creates an opportunity to more equitably distribute resources.

Bhatia’s approach of designing to increase equity and accessibility rises out of his work as the founder of The Open Workshop in San Francisco, whose recent projects include “This Land is Your Land,” a “multi-resource cooperative” in the rapidly growing Tennessee Valley, a research proposal to provide affordable housing to diverse populations and increase broadband access. The firm’s 2021 Chicago Architectural Biennial project, “Decentering the Commune,” proposed a design for an urban commons in Bronzeville, making use of publicly owned vacant lots to provide a “network of sharing” between existing organizations, offering Chicago residents access to “food, making, ecology, and care” in ways that increase their autonomy. Finally, “Lots Will Tear Us Apart,” sited in San Francisco, a collaboration with GSD alumni Dan Spiegel and Megumi Aihara, reimagines mid-density housing typologies to “bridge lots,” catering to collective living.

In California, students had the opportunity to meet with representatives of the California High-Speed Rail Authority and visit a series of construction sites. On their return, Bhatia asked them to research a segment of the railroad, focusing on collective housing and centering opportunities for care; then, each student created their own speculative design for a station.

A Food Desert Amidst Farms

Ella Larkin (MArch ’26) and Connor Gravelle (MArch ’25) researched the Central Valley’s foodways, asking, “In a place with so much farmland, why is it so hard to get affordable, fresh produce?”

They found their answer by tracing food through the supply chain. The Central Valley harvest was first shipped to a massive consolidation center, such as those used by mass-market brand Walmart, which “aggregate goods on a territorial level before subsequent relocation to distribution centers.” Before produce reaches residents in the Central Valley, it is first shipped “upstream,” with several stops before it is transported back to a local markets, where its high price reveals the burden of its journey through a costly, time-consuming system.

Leveraging the speed of the CHSR, they designed a new system to allow fresh produce to remain in the Central Valley for longer, enabling new forms of access to residents at stops such as Kings-Tulare and Fresno.

Education on the Rail

Because educational amenities and funding are often equated to population size, people in the Central Valley face challenges in accessing educational opportunities.

Ziyang Xiong (MArch ’26) and Iam Bhunto (MAUD ’25) proposed two structures that center educational opportunities and include housing and healthcare. Finding that the Central Valley’s high school and college graduation rates are significantly lower than California’s as a whole, and that middle-skill jobs (which require more than a high school education but less than a bachelor’s) will be in demand in the coming decades, Xiong and Bhunto set out to create a new typology. To help people meet the qualifications for these jobs—for example, dental hygienist, computer technician, and EMT—they designed a “trade school with diverse and extensive shared resources,” including education centers, housing that has co-living options for students and families, and shared amenities such as a workshop and a gym.

Housing for Migrant Workers to Put Down Roots

Chloe Tsui (MArch / MDes ’27) and Inmo Kang (MArch ’25) tackled the housing shortage that the Central Valley’s migrant farmworkers face throughout the year. In the 1970s, they explained, migrant workers typically consisted of “single men who left their families behind when they traveled to California for work,” but those demographics have long since shifted.

Today, most migrant workers are “intergenerational families” who live year-round in the United States—and yet, their access to housing is limited to six-month-long rentals at state-run housing centers. Tsui and Kang found that 83 percent of families said they would remain in the homes year-round if they could; some had returned year after year for the last five to ten years.

However, to qualify, they’re required to live at least 50 miles away from the farm for a minimum of three months every year—forcing them into continual displacement. Using the CHSR, the duo provide the opportunity for migrant workers to commute across the territory, allowing them to live in one stable location while building connections and social networks. At the Bakersfield and Merced stops, they propose a series of “physical and social infrastructures for migrants,” comprised of housing cooperatives, a community kitchen, and a community center.

As more and more regions across the US plan for and construct high-speed rail systems, California will serve as an early test for what will happen to populations whose geographies have shifted due to changes in infrastructure, time, and access.

Excavating background geographies, says Bhatia, reveals what our society values. “If you want to see our relationship to energy, labor, agriculture, food—key resources that sustain us—those negotiations play out in background geographies where people also often face different forms of precarity.”

Now, as immigrants in the Central Valley face the threat of mass deportations, many too fearful to show up for work, says the California Farm Bureau, and Los Angeles grapples with the massive destruction wrought by the fires, perhaps both these polarized populations—soon to be intertwined via the CHSR—can find mutually beneficial solutions through an armature for care and equity-centered design.

Shana M. griffin on Resisting Reproductive Violence in the Built Environment

For the last three years, Shana M. griffin has been collecting soil, nineteenth-century nails, acorns, and fragments of bricks from sugar plantations along the Mississippi River in southeastern Louisiana. Now, in her Harvard ArtLab studio, the rusty, hand-hewn nails sit in a jumble inside a large glass jar, bearing silent testimony to the labor that went into making and using them, by people whose lives were shaped by racial violence. Beside the table stand two figures in coarsely woven cotton dresses, a crown of upside-down nails atop one of their heads. Beside the door, she has posted a list of women’s names and nineteenth-century dates—the year they ran away and were listed in New Orleans newspaper runaway slave ads and jail notices.

griffin says she is “excavating people out of the archive. How do I create a narrative that’s historically based on their lives?”

An activist, artist, sociologist, and geographer, griffin is the Graduate School of Design’s 2024–2025 Loeb/ArtLab Fellow . She works from a foundation of Black feminist theory to question and reimagine spatial politics. This winter at the GSD, griffin offered a J-Term course, “The Political Economy of Reproductive Violence in the Built Environment: Critical Conversations Towards Intersectional Feminist Spatial Practices.” In a pair of two-hour sessions, she asked GSD students, who attended both in person and via Zoom, to consider how reproductive violence is interwoven with the built environment, from historical and contemporary perspectives. She defines reproductive violence as “the methods used to sustain reproductive oppression and reproductive subjectivity—institutional and systemic control of the sexuality and reproductive lives of women and marginalized communities.”

In order to understand that history and context, griffin turned back to the colonial era in the United States, explaining that mercantilism—generating products to export so the nation could develop a profitable economy—pushed white settlers to attempt to erase Indigenous people through genocide. Colonists used “sexual violence, disease, and the systemic killing of Indigenous women and children during massacres,” griffin explained. By controlling Indigenous women’s bodies, white settlers controlled their land.

Similarly, European’s enslavement of Africans and African Americans included the “control of reproduction for the production of profit,” as well as forced labor to “clear forests and swamps, build roads, houses,” and everything else required to develop the nation. Tracing US policies across hundreds of years to the present day, griffin illustrated how white colonists have long attempted to control Black women’s bodies and “discourage the reproduction of Indigenous, Black, and women of color”—for example with mandated birth control, the “criminalization of women of color and queer communities’ sexuality and motherhood,” the exclusion of immigrants and Latinx women, presenting “Arab and Muslim women’s reproduction as a terrorist threat,” and “coercive incentives,” among many others.

While most people are aware of how racism is made manifest in the built environment, griffin explains, “racialized gender policies” are “often rendered invisible” in our landscape, infrastructure, buildings, and cities.

“Whenever you talk about housing,” she explained, “whether you say it or not, you’re talking about gender.”

Homeowners have access to security and equity; affordable housing is stigmatized, especially for Black mothers, and the materials that create those structures are substandard. In addition, she added, Americans are supposed to be safe inside our own homes, but, as in the case of Breonna Taylor, police entered her home and killed her. griffin described housing policies built on the nation’s racist systems, starting with enslaved people’s confinement in plantation houses, to issues such as racial zoning, systemic divestment from neighborhoods, “urban renewal” that displaces communities of color, redlining, subprime mortgages, and foreclosures. She shared images of 1930s posters by the US Housing Authority with the headlines, “Slums Breed Crime” and “Cross Out Slums.”

Her interdisciplinary work as an artist and activist rises out of her resistance to systemic racism and sexism. In DISPLACED , a book art, atlas, community center, and New Orleans walking tour project, griffin explains how slums, blight, and increased incarceration rates for Black people result in, as one page of the DISPLACING Blackness chapbook reads, “Black Disposability and Displacement.” griffin writes, “In neighborhoods that are majority Black, one in four renters experienced a court-ordered eviction,” while in white neighborhoods, only “one in twenty-four renters” are evicted. Aiming to mitigate these disparities, griffin has planned a “multiuse art space for communal infrastructure building and civic engagement,” with a research lab, gallery, and activist studios.

During the walking tours, “Geographies of Black Displacement,” griffin invited listeners to recognize other racist ideologies and histories that have formed New Orleans: “land-use planning, housing policy, and development, starting with the violent formation of New Orleans as a carceral landscape and colonial enterprise of extraction, enslavement, genocide, and conquest.” And, her interdisciplinary project, PUNCUATE, responds to the “violent subjugation and objectification of Black women’s bodies, reproduction, and sexuality,” with research, art, publications, activism, and pop-up stores.

Like SOIL, the project for which she gathers nails, soil, and bricks from plantations, her book Theirs Was A Movement Without Marches: Black Women in Public Housing creates a “counter-archival narrative,” using photographs and essays to reintroduce to public record women whose work was forgotten. The book celebrates Black women organizers who helped improve conditions in New Orleans public housing, where griffin herself grew up. While she always knew of her mother’s work as an activist, she was pleasantly surprised to come across an archival photo of her—Mrs. Irene B. Griffin—delivering a meal to elderly residents as part of her work as president of the Iberville Residents’ Council. Mrs. Irene and her co-organizers are listed in the book, in recognition of how they improved living conditions in the apartments and grounds, organized programs for children and the elderly, and advocated for the rights of people living in public housing.

SOIL is part of the 2023-2024 group show Finding Grounding at Barnes Ogden Art and Design Complex Gallery in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and in the 2023 solo exhibition “ERASED / Geographies of Black Displacement ,” at Fordham University’s Ildiko Butler Gallery. “ERASED” also includes paintings from her “Cartographies of Violence” series—maps caked in black paint and swirled into waves—as well as rooms she designed to bring to life the late nineteenth-century parlor entrance of the White Rose Mission, founded in 1897 Manhattan by Victoria Earle Matthews, a writer and activist who was born into enslavement and then emancipated, and Alice Dunbar-Nelson, a Harlem Renaissance poet. The White Rose Mission was in the San Juan Hill neighborhood of New York, an African American community displaced in the 1950s for “urban renewal,” and replaced with Lincoln Center and Fordham University’s Manhattan campus. griffin reimagines the Mission space, down to replicated business cards and Victorian era furnishings, once again excavating women’s stories from the archive to recognize their contributions.

And, for the 2022-2023 exhibition “First Frame: The Preludial exhibition of SEEING BLACK: Black Photography in New Orleans 1840 & Beyond,” at the New Orleans African American Museum, griffin designed and furnished Florestine Perrault Collins’ studio as she imagined it might have looked when Collins worked there. Collins was the first documented Black woman photographer in New Orleans.

griffin is currently at work on a series of sculptural waves reminiscent of bodies emerging from the water, referencing the Middle Passage and the waterways around Louisiana’s sugar plantations. And, in addition to creating her own work, she’s curated shows on photography and the intersection of race and water in contemporary art.

In concluding her course this winter, griffin asked the class to consider what a feminist city might look like, and, if control and regulation of the built environment starts with control and regulation of our bodies, how we can form our own sites of resistance. If we don’t want to reproduce violence, what are we aiming for? She left students to consider the questions: “How is the legacy of slavery spatialized in the built environment? How is colonial violence implicit in the production of space?” Following her lead, the answers might be found by sinking deeply into our geographies to come to know the histories that surround us, starting with the dirt at our feet.

“In thinking about slavery through soil,” said griffin, “soil becomes the witness.” It allows her to engage with the history of enslavement without reproducing its violence in images.

She left students to consider how they might develop their own feminist spatial practices, and how they could apply care to reimagine the built environment and right some of these wrongs—questions especially relevant in an era that has many looking to history for a path forward.

What Musicals Teach Us About Cities

We often think of musicals—whether on stage or screen—as vehicles for catchy tunes and flashy dance numbers. These productions, however, are far more than entertainment. Rather, musicals convey specific knowledge, teaching us about their locales and the people who occupy them. This premise underlies “Understanding Urban Landscape through Art and Musicals,” a Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) J-Term course taught by Trinity Kao (MAUD ’25). Each year prior to the spring semester, GSD students, faculty, and staff are invited to teach non-graded workshops that explore unique, experimental topics. In her J-Term course, Kao positions musicals alongside photographs, paintings, and other works of art as intimately tied to their cultural contexts.

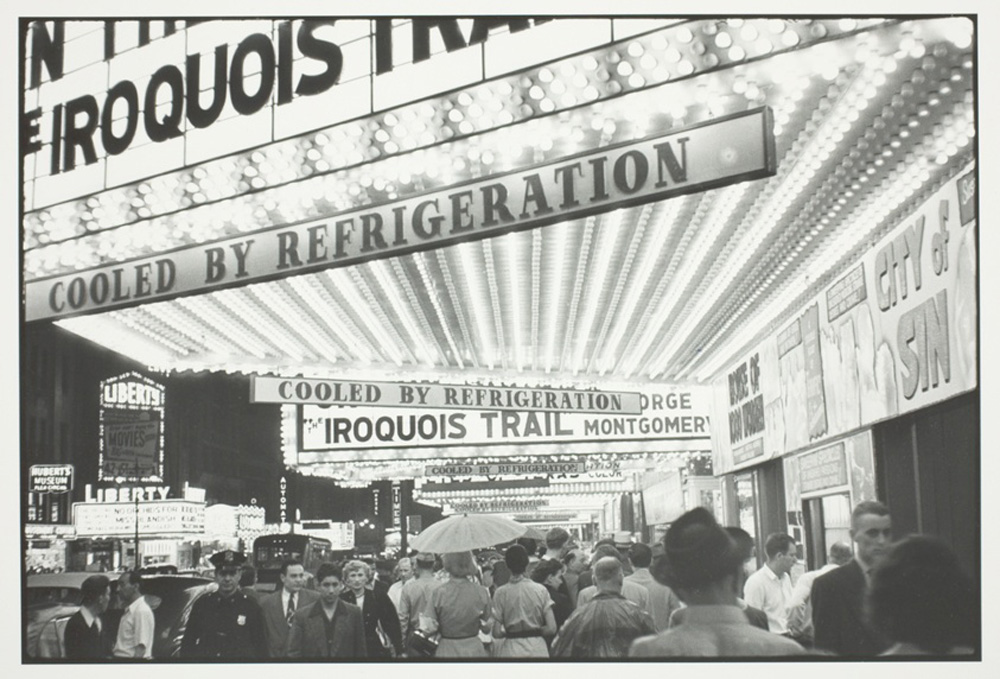

Growing up in Taiwan, Kao was drawn to musicals because they offered insight into American culture, especially the urban environments in which musicals often take place. While maps may delineate district boundaries, street locations, and building adjacencies, musicals offer more nuanced information. The musical West Side Story, for example, conveys the racial tensions that pervaded 1950s Upper West Side Manhattan, alongside the neighborhood’s characteristic fire escapes, roof tops, and highway underpasses. By watching even a portion of the musical, we can quickly acquire a sense of the cultural and physical environment of the particular time and place. And significantly, as Kao notes, “the musical is a form of media understandable by everyone,” no special training required.

Throughout the course, in total three 90-minute sessions, Kao introduces nearly a dozen musicals, including Legally Blonde, Little Shop of Horrors, In the Heights, and 42nd Street. The preponderance of musicals that Kao discusses take place in New York City or Los Angeles, save for a few outliers such as Hairspray (Baltimore); Oklahoma (Oklahoma City, Nebraska), and Waitress (the American South). Speaking of American musicals, Kao points out that, while none are situated in Santa Fe, both Newsies and Rent contain songs about the New Mexico city, fashioning it as a utopian respite from urban chaos.

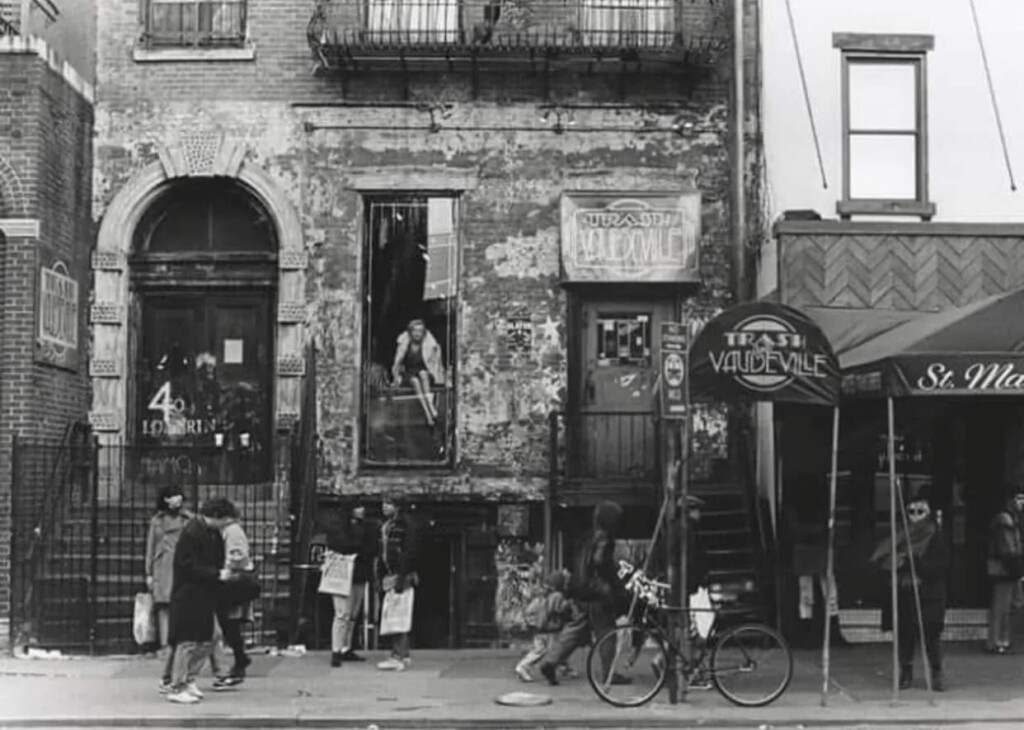

Indeed, the notion of utopia markedly contrasts with the difficult lives described in productions such as Rent. Opening on Broadway in 1996, Rent echoes Puccini’s opera La Bohème (1896), which focuses on a group of poor artists in the Parisian Latin Quarter circa 1830. A late twentieth-century interpretation of its predecessor, Rent relocates the action to Manhattan’s Lower East Side (East Village), a ramshackle neighborhood-turned-haven for Bohemians facing the myriad pressures of poverty, gentrification, and the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s. No map could convey the predicament faced by the musical’s characters, squatters in a derelict apartment, who amid winter’s bitter chill rely on indoor bonfires for warmth and candles for light. Nor could a map communicate the avarice behind the developer-driven scheme to redevelop this property, despite displacing the struggling artists and the unhoused people who live on the lot next door.

In such a manner, musicals have the power to illuminate the lived experience of a city at a specific moment in time. Simultaneously, their adaptations underscore continuities throughout time. Elaborating on Rent and La Boheme, Kao notes that, despite the hundred years that separate the two stories, “we see the same kind of people living in the two cities. These people have the same kinds of dreams, the same types of struggles, even as the urban structure keeps changing.” Musicals, then, not only teach us about cities; they elucidate enduring aspects of the human condition.

Photo Credits

West Side Story: ©Disney.

Faurer, Indian Summer: Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, transfer from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. Copyright © Estate of Louis Faurer. Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

East Village: Photographer unknown. https://medium.com/@michaelcline2323/saint-marks-place-east-village-nyc-a08600b29b66.

Announcing Spring 2025 Public Programs and Exhibitions

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) announces its spring 2025 public programs and exhibitions, with many events highlighting how we visualize and understand design in context.

The exhibition Envisioning Cluny: Kenneth Conant and Representations of Medieval Architecture, 1872–2024, on view in the Druker Design Gallery (through April 4), focuses on how medieval monuments inspired the evolution of modern architectural visualization techniques. Curator Christine Smith brings together photographs, drawings, plaster casts, and recently created 3D models of capitals from the twelfth-century monastery complex at Cluny, France, to suggest previously unimagined possibilities for future scholarship. The opening event, Sounds of Medieval Cluny (January 30), will conjure the monastery through music: a vocal performance by Blue Heron and commentary by musicologist Thomas Forrest Kelly.

Renowned designers Kengo Kuma (April 8), Dorte Mandrup (February 13), Minsuk Cho (March 13), and Jala Makhzoumi (March 11) share architecture and landscape projects that cultivate symbiotic relationships between buildings and their sites. On March 6 and 7, the conference African Landscape Architectures: Alternative Futures for the Field examines the multifaceted ecologies, materialities, and identities of African landscapes with designers working across the continent. The conference’s keynote, the 2025 International Womxn’s Day Lecture (March 6), features a dialogue between Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi of the Osun Sacred Grove in Osogbo, Nigeria, and Tarna Klitzner, founder of TKLA in Cape Town, South Africa.

The spring’s programming also highlights creative practices that tackle pressing social and political issues. The Just City Lab will kick off the fifth annual Mayors’ Institute on City Design Just City Mayoral Fellowship (February 6) with civic leaders discussing strategies to address racial, social, and environmental injustice in our cities. Deanna Van Buren (March 4) advocates prison abolition, Maurice Cox (March 25) addresses inequality in Chicago’s public space, and Peter Barber (April 3) designs and champions affordable housing in the UK. In response to the worsening housing affordability crisis, the Joint Center for Housing Studies hosts The Evolving Landscape of Social Housing in New England on April 18, bringing together practitioners, policymakers, advocates, and researchers to examine new models of social housing in the region.

These planners and designers shape our cities; artists’ images, performances, and sculptures question our worldviews. Philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne (February 3) unpacks the role of African Art in the universal museum. Internationally renowned photographer An-My Lê seeks “to photograph the landscape in such a way that it suggests a universal history, a personal history, a history of culture” (April 1). Tunde Wey explores exploitative systems in a variety show, VIEW FROM THE EDGE! On Periphery-Center Relationships (April 10). Finally, on April 17, Ximena Caminos shows how The ReefLine, an underwater sculpture park in Miami, helps to restore the city’s marine ecosystems.

The complete public program schedule appears below and can be viewed on Harvard GSD’s events calendar. All events will be livestreamed on the GSD website unless otherwise noted. Please visit Harvard GSD’s home page to sign up for periodic emails about the school’s public programs, exhibitions, and other news.

Sounds of Medieval Cluny with

Christine Smith, Thomas Forrest Kelly, and Blue Heron

Exhibition Opening and Reception

January 30, 6:30pm

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, “African Art and Universal Museums”

Aga Khan Program Lecture

February 3, 6:30pm

Mayors Imagining the Just City: Volume 5

Panel Discussion

February 6, 6:30pm

Dorte Mandrup, “Conditions of Place & Form”

Kenzō Tange Lecture

February 13, 6:30pm

Deanna Van Buren, “Designing for Abolition”

Jaqueline Tyrwhitt Urban Design Lecture

March 4, 6:30pm

African Landscape Architectures: Alternative Futures for the Field

Conference

March 6–7

Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi and Tarna Klitzner

International Womxn’s Day Keynote Address

March 6, 6:30pm

Jala Makhzoumi, “Landscape, Garden, and a Colonial Legacy”

Aga Khan Program Lecture

March 11, 6:30pm

Minsuk Cho, “Notes on Time”

Lecture

March 13, 6:30pm

Maurice Cox, “The Design of Power Sharing: Chicago’s South and West Sides”

Carl M. Sapers Ethics in Practice Lecture

March 25, 6:30pm

Jorge Otero-Pailos, “Distributed Monuments”

Lecture

March 28, 12:30pm

An-My Lê, “Maps & Legends: Photography Between Histories and Beyond Borders”

Rouse Visiting Artist Lecture

April 1, 6:30pm

Peter Barber, “Reimagining Social Housing”

John T. Dunlop Lecture

GSD Open House, April 3, 6:30pm

Cambridge Talks: Acts of Scaling

Symposium

April 4–5

Kengo Kuma, “Return to Nature”

John Hejduk Soundings Lecture

April 8, 6:30pm

VIEW FROM THE EDGE! On Periphery-Center Relationships

Tunde Wey

Variety Show

April 10, 6:30pm

David Sheldon-Hicks, “Future Mapping”

Lecture

April 15, 6:30pm

Ximena Caminos, “The ReefLine”

Lecture

April 17, 12:30pm

The Evolving Landscape of Social Housing in New England

Symposium

April 18, 1pm

Brian D. Goldstein, “‘These Contradictory Things’: Max Bond’s Harvard”

Lecture

April 23, 6:30pm

Thinking Through Soil

Book Release

April 24, 12:30pm

Unifying Research and Practice: Sam Naylor

As a Harvard Graduate School of Design Druker Fellow, Sam Naylor (MAUD ’21) traveled the globe to investigate cooperative housing, exploring more than 100 projects over three years. Simultaneously, Naylor worked as an architect full time, co-authored three major housing-related reports, and sustainably renovated a cooperatively owned triple-decker in the Jamaica Plains neighborhood of Boston. Uniting these endeavors and driving this improbably large aggregation of work is Naylor’s abiding interest in housing—what it is, and what it can be—alongside his conviction that research and practice enrich one another.

Naylor’s architectural studies began in 2011 at Tulane University’s School of Architecture, in New Orleans. This was less than a decade after Hurricane Katrina, and the school immersed students in the city’s reconstruction. “Because it was so hands-on, and we were building real things that would happen in different neighborhoods, the design-build program was a big part of what inspired my architectural thinking,” Naylor says. In addition to individual architectural interventions, “there was also a focus on the city itself, working with community members and rebuilding at multiple scales, in a really considered way that was engaged and ecologically specific.”

Following Tulane, from which he graduated with bachelor and master of architecture degrees, Naylor’s experience of thinking about design at multiple scales accompanied him to Los Angeles where he worked for a few firms “on a wide range of architectural projects, from the city scale down to furniture. Slowly,” Naylor recalls, “I became more political and wanted to understand the dynamics behind our cities and what makes it possible for things to happen. What hidden forces set up the game for us as architects? I was curious to see how I in my career, and architects and designers in general, could have more agency in establishing the rules of the game that we then play.” This thinking led Naylor to the GSD, where he began his post-professional MAUD studies in 2019.

Looking back, Naylor describes his two years as a GSD student as “a critical part of my career, a great time to slow down, read and research more heavily, and take classes in different disciplines.” By the second semester, Naylor found himself drawn to housing. “As a design area,” he explains, “housing embodies a lot of the elements in which I’m interested. Housing transitions scale; you have to think about the city, and also about the room and furniture scales, even door handles. It’s also extremely political; you have to be engaged in the world, thinking about the processes through which design and construction will actually occur.” Finally, “housing is intimately connected to our own lives,” Naylor says. “And with the current housing crisis, it is satisfying to work on an issue that matters. Designing housing for communities where I live or work or that I care about is extremely fulfilling.”

Fortunately, the GSD proved an excellent place for Naylor to explore housing as a student and beyond. Graduating from the MAUD program in 2021, Naylor was awarded the Druker Traveling Fellowship, which sponsored his three-year study of cooperative housing design , exploring models in nearly a dozen countries from Argentina to the Netherlands to Australia. Toward the end of the 2021, Naylor was also appointed a research fellow at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) where, with associate professor in practice of urban planning Daniel D’Oca and professor in practice of landscape architecture Chris Reed, he co-edited The State of Housing Design 2023 , the first book in a new series that addresses issues related to residential design.

Meanwhile, Naylor joined Utile, a Boston-based firm founded by Mimi Love and Tim Love (MArch ’89, also a lecturer in real estate at the GSD). At Utile, Naylor is currently an associate with a focus on multifamily housing, as well as a member of the internal housing research team, which investigates housing and policy-related best practices. In October 2024, Naylor with Utile, JCHS, and the research center Boston Indicators released “Legalizing Mid-Rise Single-Stair Housing in Massachusetts,” a report examining the space-saving benefits of eliminating multiple-stair mandates in this building type. The single-stair report is the first step in “the harder work of making that regulatory change possible,” with Naylor now “meeting every week with people in co-development, housing advocacy, municipal policy, or the state legislature to talk about how we can make that happen.” In addition, Naylor is concurrently working with Tim Love, Amy Dain, and Camille Wimpe on Equitable Zoning by Design , a research project at Northeastern University that explores rezoning for multifamily development following MBTA guidelines, with findings to be released this month.

Concerning the potent mix of research and practice that comprises his career, Naylor feels fortunate to be a part of a firm that supports research and exploration. “It would be advantageous if more places we work supported these tangents because they enrich everything—your work, your connections, your design thinking. Research and practice improve each other,” Naylor affirms. “Research informs theory and then comes back into practice. It’s a form of testing ideas iteratively.”

This philosophy appears to hold sway in Naylor’s personal realm, notably in his very intentional living arrangements. Naylor, his wife Elaine Stokes (MLA ’16, DDes ’25), and a few friends cooperatively own a triple-decker house in Jamaica Plain. They purchased the property and have since embarked on a collective journey to decarbonize, renovate, and reside together, in their individual units, sharing building maintenance, some meals, and dog care responsibilities. Not coincidentally, during the years that Naylor traveled the globe to investigate cooperative housing projects, back at home he initiated his own—a true unification of research and practice.