Independent Study by Candidates for Master’s Degrees

Students may take a maximum of 8 units with different GSD instructors in this course series. 9201 must be taken for either 2, or 4 units.

Prerequisites: GSD student, seeking a Master's degree

Candidates may arrange individual work focusing on subjects or issues that are of interest to them but are not available through regularly offered coursework. Students must submit an independent study petition and secure approval of their advisor and of the faculty member sponsoring the study.

The independent study petition can be found on my.Harvard. Enrollment will not be final until the petition is submitted.

Radical geometry: With Haus Gables, Jennifer Bonner proposes a new urban typology

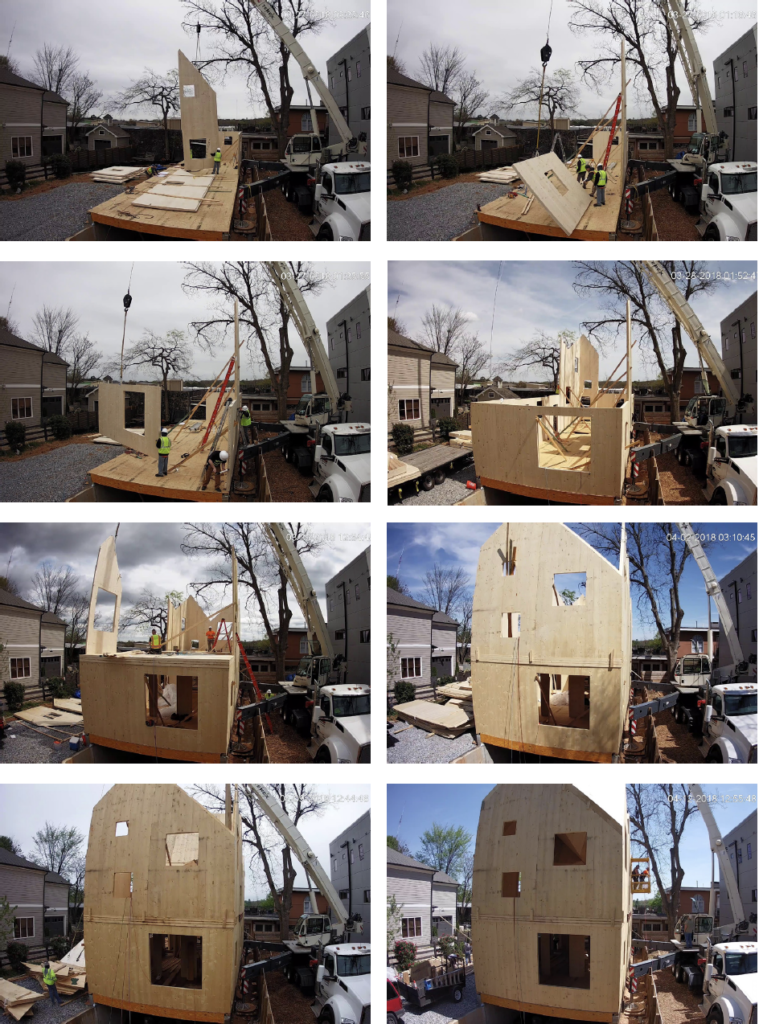

On the first day of the construction of Haus Gables—after 11 trucks had ferried 87 panels of cross-laminated timber from Savannah to Atlanta—Jennifer Bonner was stuck in Cambridge due to a last-minute travel snafu. So she watched her first built project come to life via security camera from a thousand miles away.

“The whole thing looked like an architectural model being assembled in place,” the designer recalls. “If you squint your eyes, watching the panels being installed at that scale, one could imagine, ‘This is the way we cut up materials—chipboard, foam core, and whatever else is on our desks—and make models.’”

Sitting on an 18-by-55-foot floor plate in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward, Haus Gables represents the third physical iteration of a research agenda that Bonner has been pursuing at her firm, MALL , over the past decade: What happens when architects start with the roof? If we let roof typology organize the rest of a building, might we start generating new forms of urbanism?

It’s a concept Bonner first presented in her 2014 exhibition, “Domestic Hats.” After studying roof typologies throughout Atlanta, she cataloged 50 different houses and milled their roofs as foam “hats.” Her next iteration, “The Dollhaus,” presented a 1-to-12-scale wooden model of a suburban home topped by oddly gabled rooflines. In producing each exhibition, Bonner researched, metabolized, then reframed the common language of suburban roofs, in a nod to the unseen complexities and cultural residues embedded within something so ordinary.

Haus Gables is “The Dollhaus” brought to life. And it was an enormous risk: Bonner took on the role of designer-as-developer-as-financier, shouldering all project liability on her own.

“The process was actually incredibly liberating,” Bonner says. “This is what the architect should be doing: building, but also conceptualizing architecture, with one foot in academia, in experimentation.”

MALL is an acronym for “Mass Architectural Loopty Loops,” and with Haus Gables, Bonner has produced the sort of project that the firm promises and celebrates. She began by taking three pairs of gables and organizing them such that, from the front-curbside view of the house, the roof appears at a typical gable pitch. However, thanks to a clever rotation, the observer sees that the traditional gable outline is a bit clipped, making something feel slightly off.

The underside of this multi-gabled roof is a folded, geometric ceiling on the home’s interior. In the interest of revealing this ceiling geometry, Bonner manipulated cross-laminated timber (CLT) like a piece of origami. This non-traditional approach required a rethink of the horizontal structural systems common to roofs, like the eave-to-eave connections that often double as an attic or loft floor. Bonner tackled this challenge alongside Haus Gables’s project engineer Hanif Kara, a longtime mentor as well as Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology at the GSD and design director of structural engineering firm AKT II.

“With Haus Gables, there are no ties in the roof, but the roof’s form acts as a shell structure through the folding of the CLT,” Kara observes. “This system is rigid in itself. We then have to take care of externally applied horizontal forces, such as wind.”

It is from this roof geometry that the inflections and space of the rest of the house follow, allowing Bonner to max out the modestly-sized floor plate. This effect, in turn, satisfied Bonner’s ambition to create wide, airy volumes within the 2,200-square-foot space. A viewer can see up to the ceiling from a few points on the first floor, and the inverse applies on the second floor: Someone standing there can see a periphery of spaces on the ground level.

“It’s four times bigger inside than it is outside,” says Mack Scogin, in an interview with Metropolis. Scogin is Bonner’s colleague at Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he is the Kajima Professor in Practice of Architecture. “As we say in the South, she’s somethin’ else.”

The CLT panels composing Haus Gables’s roof were among the 87 that Bonner had flip-milled at KLH in Austria. Each panel was designed digitally to the millimeter—Bonner checked the final design file by hand six different times—and numbered one through 87—“like cartoon panels,” Bonner observes.

“Precise industrialized off-site manufacture is one of the biggest advantages we have, since we have to have fully drawn, designed, and calculated systems, helping us avoid lack of fit on site,” says Kara. “This means there is no casualness at all in the binding of macro and micro detailing of connections. The brute force of computation and digital manufacturing is now so powerful it allows us to examine forensically the structural stresses and manufacturing constraints all in one model. This collapsing of process is all very exciting.”

After milling, the CLT panels were loaded onto three open-top containers and shipped to the Port of Savannah in Georgia, where they were packed onto hot-shot trailers heading to Atlanta. All 11 trucks were staged to receive and deliver the panels in the order in which they were to be installed, with a crane on site ready to lift the panels into place.

Bonner smiles when confessing that nearly every subcontractor who walked through the door of Haus Gables immediately scratched their head. She explains this was because not many were accustomed to working with CLT—plumbers and electricians wondered where their pipes or wires would go within walls that are solid. But perhaps the real issue was that they couldn’t find the front door.

“Yeah, there’s no front door,” Bonner admits. Instead, visitors enter through the garage, a bright-white, glossy space that reads more art gallery than automobile storage. From first glance, Haus Gables defies ordinary expectations of “house.” Faux finishes dash across the interior, with material elements including vinyl, terrazzo, and ceramic tile placed like massive stickers on the CLT walls. The master bedroom is set off by gray vinyl that resembles concrete; the dining room is bathed in a yellow vinyl that looks like marble; the kitchen is all black terrazzo. The CLT walls were whitewashed to achieve a milky hue, in effect freezing them in time to avoid yellowing.

Things get weirder on the outside. Eschewing wood siding, Bonner sought an abstract material for the exterior facades, wanting something ordinary that could be found in big-box stores. She settled on cementitious stucco. On two facades, she applied a brick stencil, an eighth of an inch thick, to the final trowel of stucco. Then, at the last second of application, she blew millions of tiny glass beads—the material used in reflective traffic paint—in a “dash finish,” creating a shimmering, reflecting façade.

In other words, the exterior is composed of fake bricks that shine like diamonds. Here, Bonner references Mary Corse, an American artist fascinated by perceptual phenomena and light, who “painted” with glass beads in the 1970s.

“I wanted to be just a little devious,” Bonner observes, noting she was unsure how brightly a 55-foot wall would shine until she saw it in action. The phenomenon doesn’t photograph: “You’ve got to be there to see it,” she says.

These various elements serve basic representational purposes, but they also get at a Southern tradition that fascinates Bonner: faux finishing, a practice with historical roots in the American South—originally a manifestation of a “fake it ’til you make it” philosophy. “There’d been an idea of, ‘We can’t afford certain materials, so let’s paint it, or apply an appliqué, or get a really thin veneer of real material,’” she says. “This was part and parcel of the notion of the house as built in the South.”

A native Southerner, Bonner waxes poetic about an early-career experience she had in deep-rural western Alabama with Rural Studio’s Samuel Mockbee, who instilled in her the notion that there can be immense intellectual value in nearly any place. She also points to Southern projects like Paul Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel and Mack Scogin and Merrill Elam’s Clayton County Library—projects of profound experimentation that lie outside today’s architectural canon.

“There are all kinds of radical projects that have happened in the South,” Bonner observes, “but that aren’t a main reference in our teaching. They are these very specific, radical experiments. I think they motivated me to create more of a dialogue around architecture in the South.”

Take Haus Gables out of its Old Fourth Ward site and, with its all-white exterior, it may read as high-modern, Japanese residential. Or, with its monolithic, overhang-free exterior, something from Switzerland. The dominance of CLT evokes Scandinavia. But we’re in Atlanta—the “Dirty South,” as Bonner reminds me. (She’s authored a book series entitled A Guide to the Dirty South, with editions focused on Atlanta and New Orleans.)

“These materials, these stickers, these colors, this kind of pop, the faux finishes—these were my ways of shaking things up a little bit,” Bonner says. “If I would say one thing about the South, it’s that it’s complicated. There needed to be a lot going on with the house to make it complicated.”

In her office, Bonner shows me a drone-filmed video of Haus Gables at dusk. As the lens pans upward, Haus Gables looks more and more like a model, sitting in front of an Atlanta skyline largely shaped by another of Bonner’s Southern design heroes, John Portman.

“I admire the invention of a typology—the super atrium—out of downtown Atlanta, and of Portman working away on his kind of architect-developer model in inventing things,” Bonner says. “He was inventing, and I’m trying to invent. To build this in Atlanta was a very important move for me.”

Developing and constructing Haus Gables involved a fair share of 20-hour days, in which Bonner would travel from Cambridge to Atlanta and then back, allowing her to teach studio at the GSD while also leading her inaugural built project to fruition. If Haus Gables is conceived as a model, a representational device, then it proved instructive for both its architect and her students.

“My students knew what I was undertaking, knew how big it was, and were so excited to hear about the process, to see a member of the junior faculty building this project,” Bonner says. “They asked me to show them the behind the scenes, the difficulties of doing such a project, what was I coming up against. I wasn’t giving them an academic lecture about a house; I was giving the down-and-dirty version.”

In a continuous braiding of research, practice, pedagogy, and mentorship, Bonner and Kara are currently planning a Spring 2020 option studio entitled “Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect.” Haus Gables stands as only one of a handful of CLT-composed houses in the US (the first, in Seattle, was designed by Susan Jones, a fellow GSD alumna). With Haus Gables as a real-life model, Bonner’s experimentation with CLT, like her decision to design from the roof, questions the very rudiments of how we design.

“One interesting thing that Hanif and I have always been discussing is how this house is really a proof of concept,” Bonner says. “To build a domestic hat at one-to-one, out of an innovative wood product like CLT, in a place that has not yet built with it—there’s a lot to figure out. It’s literally throwing all of our energy and resources into building a proof of concept.

“Maybe I’m demonstrating or rehearsing the same kind of thing the students do, which is to have a position on architecture, an agenda, a thesis,” she continues. “Work it conceptually and intellectually, and then try to deliver it. It’s like working in studio, where you’re trying to dig at the conceptual thesis of an architectural project, and then you culminate in a final review. Haus Gables is the culmination of a body of work that I’ve been working on for the past five years.”

Preston Scott Cohen

Preston Scott Cohen

In this episode, Talking Practice host Grace La interviews Preston Scott Cohen, founder and principal of Preston Scott Cohen Inc , and Gerald M. McCue Professor in Architecture at the GSD.

A teacher at the GSD since 1989, Cohen reflects upon his distinguished career as an educator and describes the ever-evolving dynamics between teaching and practice. Informed by his deep knowledge of the discipline, Cohen shares his early memories of architecture, and his belief in the catalytic role architecture must play in the transformation of our urban context. Discussing the mechanics of contemporary practice, Cohen reveals how his practice approaches the intensive process of project development with a progressive attitude, and how a permutational approach can sidestep the pitfalls of conventional value engineering. Looking back on his 2013 Walter Gropius Lecture and his 2018 GSD studio titled “The Future Provincetown,” Cohen furthers his analysis of the challenges confronting architecture today. Cohen ends by asserting his hope for a more symbiotic interaction between architecture and urban planning.

Preston Scott Cohen is the founder and principal of Preston Scott Cohen Inc , and Gerald M. McCue Professor in Architecture at the GSD, where he served as Chair of the Department of Architecture from 2008 – 2013. Cohen’s work encompasses diverse scales and types of buildings, including houses, educational facilities, cultural institutions, and urban design. His work has been the subject of a wide range of publications and exhibitions and is held in various collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. Cohen is the author of Contested Symmetries and numerous theoretical essays on architecture. In 2018, Cohen taught a studio at the GSD titled “The Future Provincetown,” which focuses on redesigning Provincetown in the face of rising sea levels.

About the Show

Developed by Harvard Graduate School of Design, Talking Practice is the first podcast series to feature in-depth interviews with leading designers on the ways in which architects, landscape architects, designers, and planners articulate design imagination through practice. Hosted by Grace La, Professor of Architecture and Chair of Practice Platform, these dynamic conversations provide a rare glimpse into the work, experiences, and attitudes of design practitioners from around the world. Comprehensive, thought-provoking, and timely, Talking Practice tells the story of what designers do, why, and how they do it—exploring the key issues at stake in practice today.

About the Host

Grace La is Professor of Architecture, Chair of the Practice Platform, and former Director of the Master of Architecture Programs at Harvard University Graduate School of Design. She is also Principal of LA DALLMAN Architects, internationally recognized for the integration of architecture, engineering and landscape. Cofounded with James Dallman, LA DALLMAN is engaged in catalytic projects of diverse scale and type. The practice is noted for works that expand the architect’s agency in the civic recalibration of infrastructure, public space and challenging sites.

Show Credits

Talking Practice is produced by Ronee Saroff and edited by Maggie Janik. Our Research Assistant is John Wang. The show is recorded at Harvard University’s Media Production Center by Multimedia Engineer Jeffrey Valade.

Integrated Design & Planning for Climate Change

This advanced research seminar in Miami-Dade County, Florida, is thematically focused within the integrated practices associated with designing and planning for climate change at an urban and regional scale. The seminar will geographically focus on urban to exurban communities—running east-west along Calle Ocho from Brickell Avenue in the City of Miami to the Tamiami Trail in the unincorporated community of Tamiami. The seminar will seek to explore the various economic and planning conventions that have paradoxically created a built environment that on one hand supports a majority of the county’s population, yet on the other hand is otherwise defined by high exposure to surface flooding, traffic-clogged streets, and an increasingly unaffordable housing stock for lower- to middle-income populations.

The seminar seeks to challenge and explore:

1. Metrics of urban service delivery;

2. Synergistic land use and housing production models in rapidly densifying districts;

3. Processes for effective and fair managed retreat;

4. Strategic obsolescence of infrastructure;

5 Novel models for strategic economic development of workforces and their associated workplaces; and

6. The designed adaptive capacity of architecture.

Course format:

Within the context of accelerated climatic, environmental, and social change, students will be required to independently select and develop a research agenda that demonstrates a command of the associated disciplinary literature framing the inquiry. In addition, each student will be required to develop analytical framework(s) that demonstrate the student’s competence for not only understanding the problem(s) but also utilizing such frameworks for practically engaging locally defined problems and stakeholders. In partnership with local stakeholders, students will travel to Miami to conduct field work to support their research. The seminar will culminate in the production of a project (e.g., memorandum, multimedia, etc.) that memorializes the analytical outcomes as well as a normative position for advancing future policy, planning, and design decisions.

Evaluation:

Students are evaluated on one survey presentation and the final research memorandum/media. Each student is required to lead discussions on relevant literature/data shaping their research as well as periodic updates concerning their research progress. Students are encouraged to utilize the seminar to ground complementary existing research for ongoing theses and dissertations.

Travel Note:

With the generous support of the Knight Foundation, some students in this seminar will travel to Miami to conduct field work and engaged local stakeholders. The enrollment for the seminar is limited to 20, and 8 of those students will be selected to travel to Miami, FL. The 20 students will be selected via the limited enrollment course lottery. The first 8 students on the list will be selected for the traveling spots, with students waitlisted for travel thereafter. Students enrolled in the option studio 1304: Adapting Miami – Housing on the Transect are encouraged to take this seminar in conjunction with the studio, but must select the course first in the limited enrollment course lottery in order to be considered for enrollment. These studio students will only travel on the studio portion of the trip. The 8 students selected to take part in the trip will be term-billed $100 and travel September 25 – September 27. Students may travel in only one course or studio in a given term and should refer to traveling seminar policies distributed via email. As part of this initiative, students may have the opportunity to continue the research developed in this seminar beyond the end of the term.

The enrollment for the seminar is limited to 20, and 8 of those students will be selected to travel to Miami, FL. The 20 students will be selected via the limited enrollment course lottery. The first 8 students on the list will be selected for the traveling spots, with students waitlisted for travel thereafter. Students enrolled in the option studio 1304: Adapting Miami – Housing on the Transect are encouraged to take this seminar in conjunction with the studio, but must select the course first in the limited enrollment course lottery in order to be considered for enrollment. These studio students will only travel on the studio portion of the trip. The 8 students selected to take part in the trip will be term-billed $100 and travel September 25 – September 27. Students may travel in only one course or studio in a given term and should refer to traveling seminar policies distributed via email.

Remembering Pei: Tracing the architect’s legacy to the Harvard Graduate School of Design

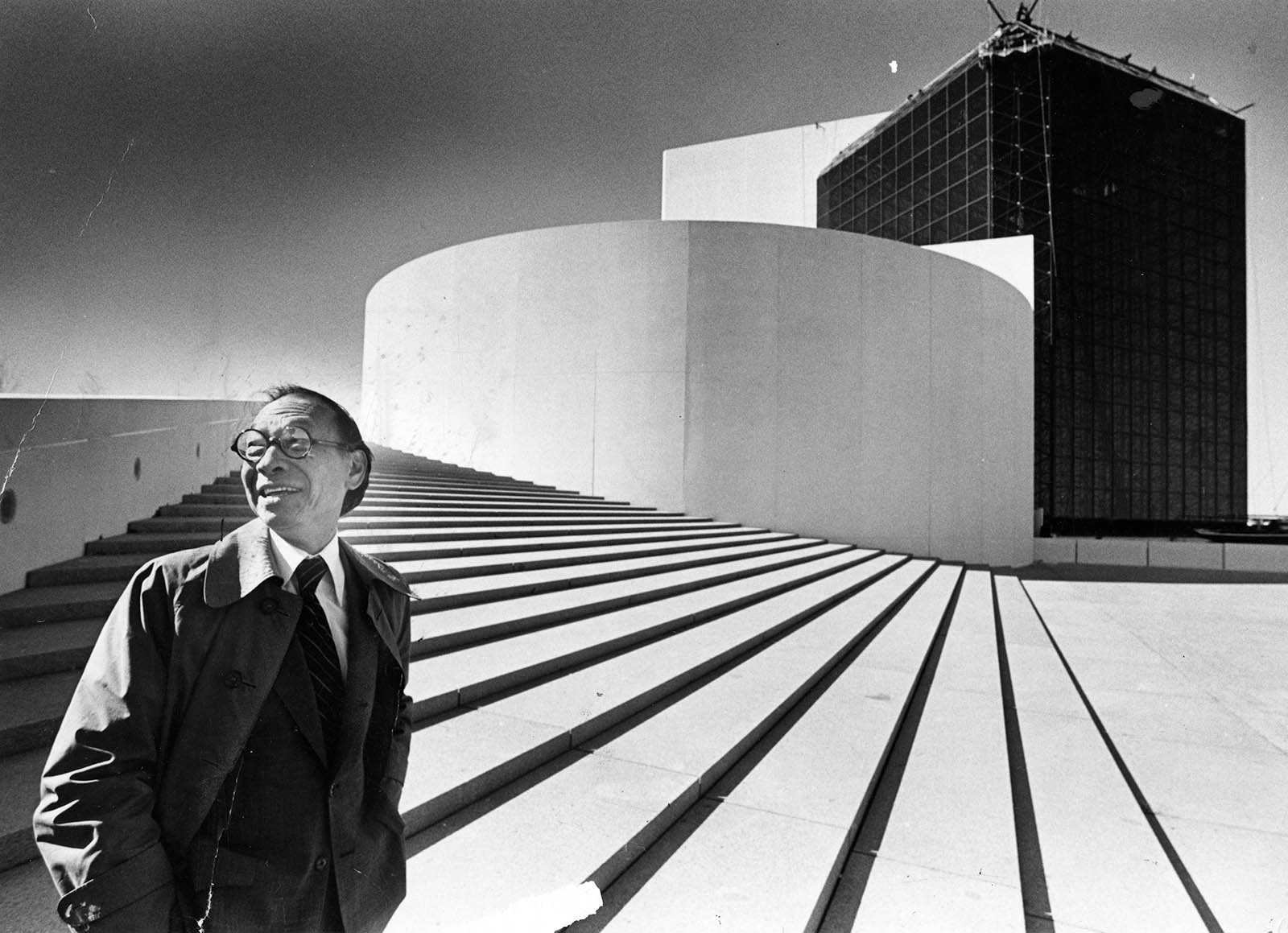

Ieoh Ming (I.M.) Pei died on May 16, 2019, at the age of 102. Over six decades, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect developed an inimitable sensitivity to form, light, environment, and history that transcended the rationalism of his Bauhaus education. The ideas he pursued and refined throughout his celebrated career can be traced back to his time at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

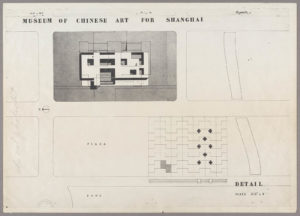

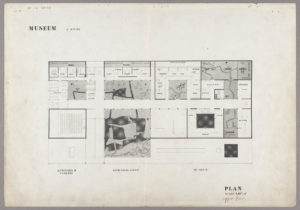

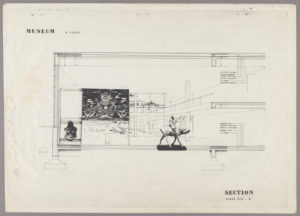

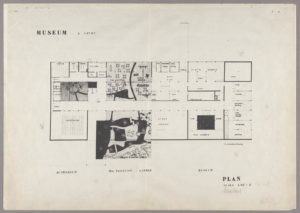

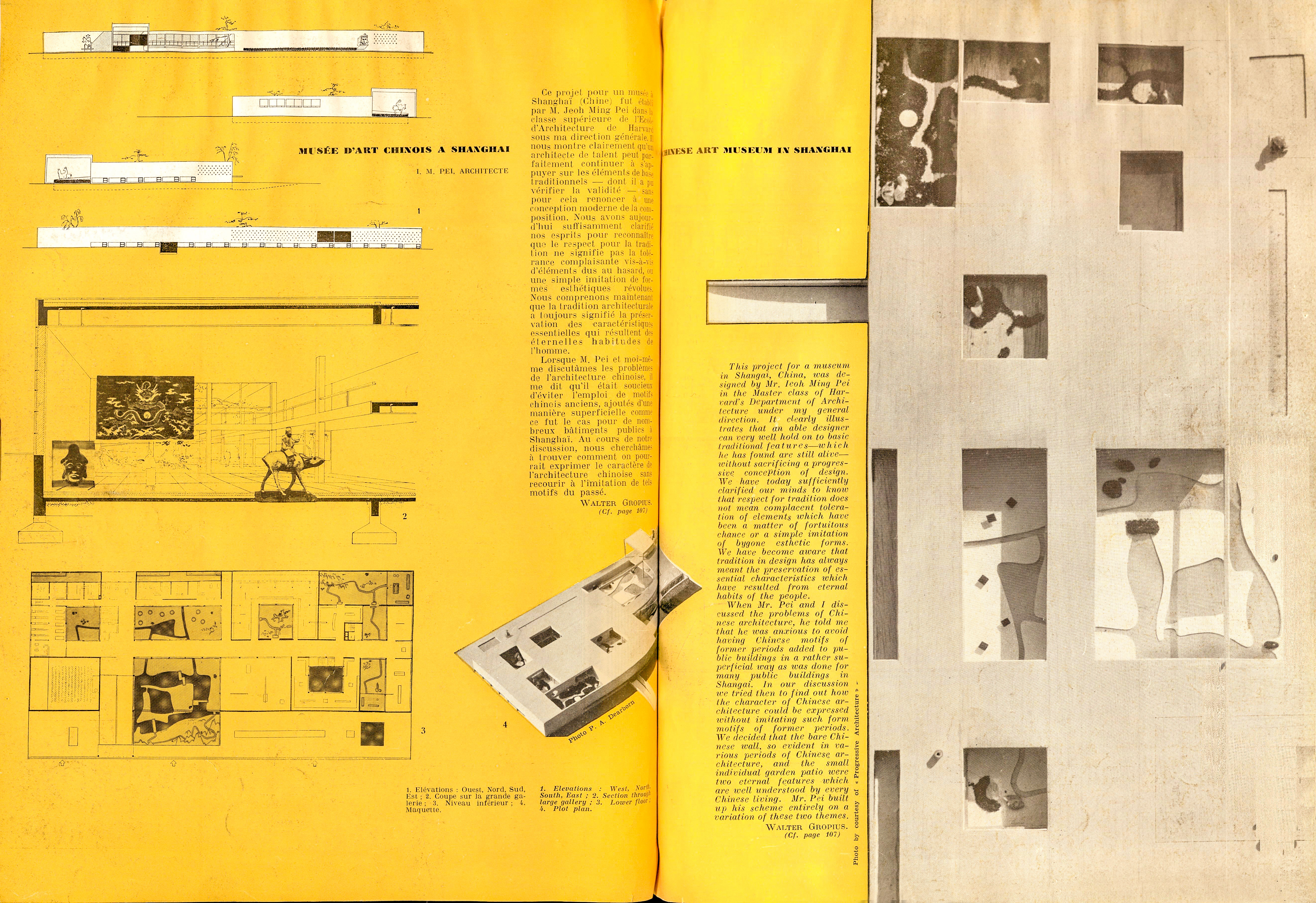

Pei came to the GSD in 1942 to study with Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and his protégé Marcel Breuer, and he stayed on after graduating in 1946 to teach for two years. His architecture thesis, a project that culminated his time as a student, was a design for a Chinese art museum for the city of Shanghai. It proposed a series of small galleries conjoined with gardens at a scale that evoked a sense of privacy traditional to Chinese art museums. But it also represented a thoroughly modern design and foretold a deepening interest in the interdependence of physical space, light, and environment—the built environment and the natural world.

“It was at that moment that I said I would like to prove something to myself, that there is a limit to the internationalization of architecture,” said Pei of the project. “There are differences in the world, such as climate, history, culture, and life. All these things must play a part in the architectural expression.” In modernism, the measure of successful architecture could be somewhat absolute, eliding cultural, historical, and ethnographic concerns, which would return to the fore in the following decades. Designing a museum for Chinese art created an opportunity for Pei to test the limit of this “internationalization,” owing to the culture-specific differences in how art objects in China and the West were commissioned and shown. Western museums housed art objects intended to be on continual public display and required vast galleries and copious wall space. Chinese art museums, by contrast, housed art objects historically intended to be brought out of storage and shown only on rare occasion and as an intimate, private experience.

Of the hundreds–if not thousands–of theses presented during Walter Gropius’ 15 years at the GSD, Pei’s stood out for the way in which it resolved a fundamental tension between the cultural and historical exigencies of a Chinese art museum and the imperatives of modernist design. Gropius sang its praises, describing Pei’s project as the best student work to come out of the GSD during his time at the school. He later published Pei’s thesis across a two-page spread in the February 1950 issue of L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, writing that Pei’s project “clearly illustrates that an able designer can very well hold on to basic traditional features—which he has found are still alive—without sacrificing a progressive conception of design.”

Pei’s project, titled Museum of Chinese Art for Shanghai, was memorably described by Henry Cobb (AB ’47, MArch ’49)—Pei’s longtime partner at Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and friend of more than 70 years—at a celebration of Pei’s 100th birthday held at the GSD on March 30, 2018. In explaining the significance and enduring relevance of Pei’s thesis, Cobb said that the project “was not just something he did on a whim. It was something of fundamental importance to him, which became directive of his subsequent professional life in a very real way… I doubt there’s ever been a piece of student work that was more predictive of a professional life to come than this project.”

Pei’s coursework at the GSD was interrupted by a two-and-a-half year stint with the National Defense Research Committee beginning in 1943—at the height of World War II—and the birth of his first son, T’ing Chung. He finished his degree in 1946, and in 1948 he began working for the real estate developer William Zeckendorf at Webb & Knapp in New York City. The 12 years that Pei worked for Zeckendorf undoubtedly was an extraordinary complement to his GSD education. He not only found himself designing skyscrapers and other large-scale projects, but in working for a developer he also was exposed to the kinds of financial and regulatory strategy, deal-making, and governmental stewardship that make substantial building projects possible. Taken together with the charm and urbane sophistication he was known for, it was an education that helped Pei secure competitive projects like the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and the addition to the Louvre Museum, a project that was initially met with fierce opposition.

In 1955, Pei founded I.M. Pei & Associates (later to become I.M. Pei & Partners, then Pei Cobb Freed & Partners), and formally broke from Webb & Knapp in 1960. As the firm gradually became independent from Zeckendorf, more and more of Pei’s own architecture became realized in building projects. Kips Bay Plaza—a low-income housing project in Manhattan undertaken for Zeckendorf—was opened in 1963 and marked an advancement in the level of aesthetic consideration then thought possible within the financial constraints of low-income housing construction. The offset composition of the site plan allowed for parks and gardens for residents, echoing the pairings of galleries and offices with Chinese gardens in Pei’s thesis project.

Kips Bay is also exemplary of Pei’s intense, career-long focus on materials and his mastery of concrete. In this case, poured-in-place facades made up of grids of delicately formed, deeply recessed windows cast crisp shadows, lending residents privacy while visually softening each building’s overall magnitude. According to Pei, the use of concrete was made possible by the tenacity of Zeckendorf himself. The cost of concrete through conventional builders was too high, but Zeckendorf’s commitment to Pei’s idea drove him to extreme alternative measures: He acquired an industrial engineering company that specialized in building highways, just to keep the cost of concrete within budget. The poured-in-place facades showed up again in projects including the Society Hill Towers in Philadelphia (1964) and the Silver Towers in New York (1967).

The years following saw the development of some of Pei’s most celebrated buildings. The National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, was completed in 1967 and was an important opportunity for Pei to explore the radical extent to which architecture could be integrated into its environment. Viewed from a distance, the complex all but disappears into the mountain it occupies. His first art museum in the U.S.—the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York—was completed in 1968. In his 2018 talk at the GSD, Henry Cobb noted in the building a consistency and evolution in composition and balance that, again, began with Pei’s thesis. Opened in 1968, the Everson Museum of Art put Pei on track to win important commissions for cultural institutions like the East Building of the National Gallery in Washington, which in turn led to his commission for the Louvre.

Over the course of his career, Pei designed a wide variety of buildings, many of them now essential fixtures of their cities—the Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas (1989), the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong (1990), and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland (1995), to name a few. But he is perhaps best known for his art museums. Following the Everson Museum of Art, the East Building of the National Gallery was, at the time, Pei’s most high-profile museum commission, and also one of his most challenging sites. The building not only needed to fit a difficult trapezoid-shaped parcel of land and correspond to the museum’s original West Building, but it also needed to reflect the monumentality of the National Mall and respect the projection of federal power embodied in the geometry of its plan. Pei resolved all of these high demands with one simple, elegant stroke: dividing the trapezoid site into two triangles, one isosceles and one right triangle. The base of the isosceles triangle serves as the East Building’s entrance, and opens to face the West Building, with its midpoint located to create a continuous east-west axis across the entire museum complex. The base of the right triangle faces east to the United States Capitol building and houses administrative offices and a study center. The pairing of these two triangles was an ingenious way of integrating the building within the overdetermined context of the National Mall while also preserving its distinct identity. On the surface, such decisions reflect a sensitivity to urban design that Pei no doubt honed during his time working with Zeckendorf, but they also reveal his keen insight into the relationship between architecture and its environment that, again, can be seen germinating in his GSD thesis and evolving throughout his career.

The East Building of the National Gallery was a near-unanimous critical and popular success, with the New York Times declaring the building one of the greatest of all time and Pei one of America’s best architects. In later years, Pei would go on to design other museums that earned global acclaim—the Miho Museum in Kyoto (1997) and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (2008), for example. His 1989 addition to the Louvre in Paris, however, will be viewed as his crowning achievement. Perhaps recognizing the daunting stakes of the project, he did not immediately agree to take it on, even after a personal entreaty from the president of France, François Mitterrand. More than 300 years earlier, French architect François Mansart had submitted at least 15 proposals to renovate the Louvre, all of which were rejected. Subsequently, at the invitation of Louis XIV, Italian architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini submitted four proposals that met the same humiliating fate. After a series of secret research trips to Paris to visit the museum, however, Pei came to believe that he should accept the commission, and he also concluded that “something must be done” about the Louvre’s dire condition.

Built in successive waves since the 12th century, originally as a fortress for soldiers and munitions, the Louvre has been adapted to accommodate a range of functions, and it presented Pei with many steep challenges: The main entrance was located along the Seine, facing south and away from the museum’s neighboring buildings and streets; the central courtyard, Cour Napoléon, was relatively neglected and being used as a parking lot for the Ministry of Finance; the serpentine floorplan was disorienting for visitors; and only 10% of the building’s square footage was dedicated to non-gallery uses like storage and administration (in the 1980s, the standard was 50%).

Much like his approach to the East Building of the National Gallery, Pei’s idea for the Louvre was at once amazingly simple and brilliant in the way it resolved a highly complex set of issues into a celebrated national icon. In excavating Cour Napoléon and adding a subterranean main entrance below the glass pyramid at its center, Pei created desperately needed space for museum staff, opened the museum to greater public access from neighboring buildings and adjacent streets on the Right Bank, and simplified navigation for visitors. He shifted the museum’s center of gravity to its central courtyard, thereby transforming what had been the inhospitable and neglected heart of the U-shaped complex into a welcoming and active public square that showcased the Louvre’s existing architecture as its backdrop.

The project drew on all of Pei’s powers as an architect, urban designer, cultural sophisticate, and political tactician. His plan fully depended on—indeed, was set in motion by—President Mitterrand’s order that the Ministry of Finance, which occupied the Louvre’s northern wing (Richelieu), would be relocated elsewhere, and that the museum would expand to become the building’s sole occupant. Mitterrand’s authority to order such a drastic reorganization of the museum, however, was predicated on the consolidation of his political power, which was diminished after Jacques Chirac, leader of one of the opposition parties, was elected prime minister. Meanwhile, even though the most significant aspects of Pei’s plan would occur underground, it was the glass pyramid that became the main focus of swift and intense public outrage. The design was loudly derided as a “gigantic ruinous gadget,” an “annex to Disneyland,” and perhaps most acerbically, at least in 1980’s Paris, “a fake diamond.” The director of the museum, André Chabaud, resigned over it. When Pei unveiled the design to the Commission Supérieure des Monuments Historiques, the assault on his proposal became so intense that the translator is said to have burst into tears and withdrawn from the meeting.

Pei, however, remained undeterred and doggedly confident in the quality and logic of his plan, and rode the waves of critique while advancing his own strategy to reverse the tide of public disapproval. He hedged his good relations with President Mitterrand by cultivating a rapport with Chirac, one of Mitterrand’s leading political opponents who, prior to being elected prime minister, was mayor of Paris. As political fortunes shifted back and forth, Pei was able to steer a course forward as excavation and construction proceeded. He also was able to enlist some of France’s most prominent cultural figures to his cause: Pierre Boulez, the orchestra conductor, and Claude Pompidou, the widow of former prime minister and president Georges Pompidou, both rallied for Pei’s plan.

The turning point came when Chirac requested that a full-scale mock-up be prepared and shown to the public. For this, a crane was brought to Cour Napoléon to hoist cables to show the pyramid’s size and outline. The cables were left suspended from the crane for four days, during which an estimated 60,000 people visited the Louvre to see the mock-up firsthand. In response, Chirac declared the design to be “not bad”—an unequivocal gesture of approval, coming as it did from President Mitterrand’s political adversary—and praise for the project gained momentum and began spreading. Media outlets that once lambasted Pei’s proposal expressed their admiration. In March 1989, the pyramid and the new underground entrance to the museum opened to the public, making the Louvre the largest museum in the world and garnering enthusiastic international acclaim.

The Louvre will likely remain Pei’s most well-known achievement—certainly the most popular—but it also stands as the culmination of his developed sense of history and tradition and their role in modernism, the composition of space and light, and the relationship between architecture and its environment. The contrasting figure of the pyramid in particular represents a formal perfection that at once foregrounds, reflects, and disappears among the centuries-old buildings and Parisian sky that surround it. No less than the soul of France had been trusted to Pei’s hands, and he succeeded famously in elevating its history and prominence while bringing the building up to late 20th-century standards.

Ieoh Ming (I.M.) Pei (MArch ’46) was married to Eileen Loo Pei, who studied landscape architecture at the GSD. They had been married 72 years when she died in 2014. I.M. is survived by their two sons, Chien Chung (Didi) Pei (AB ’68, MArch ’72) and Li Chung (Sandi) Pei (AB ’72, MArch ’76), their daughter Liane Pei, and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. I.M and Eileen’s eldest son, T’ing Chung Pei (AB ’65), was an urban planner and died in 2003.

Visualization (at SEAS)

This course is an introduction to key design principles and techniques for visualizing data. It covers design practices, data and image models, visual perception, interaction principles, visualization tools, and applications, and introduces programming of web-based interactive visualizations.

Prerequisites: Students are expected to have basic programming experience (e.g., Computer Science 50).

See my.harvard, SEAS COMPSCI 171, for location

Computer Vision (at SEAS)

This course explores vision as an ill-posed inverse problem: image formation, two-dimensional signal processing; feature analysis; image segmentation; color, texture, and shading; multiple-view geometry; object and scene recognition; and applications.

See my.harvard, SEAS COMPSCI 283, for location

Innovation in Science and Engineering: Conference Course (at SEAS)

The course explores factors and conditions contributing to innovation in science and engineering; how important problems are found, defined, and solved; roles of teamwork and creativity; and applications of these methods to other endeavors. Students will receive practical and professional training in techniques to define and solve problems, and in brainstorming and other individual and team approaches.

Course format: Taught through a combination of lectures, discussions, and exercises led by innovators in science, engineering, arts, and business.

See my.harvard, SEAS ENG-SCI 139, for location

Materiality, Visual Culture, and Media (at AFVS)

What is the place of materiality in our visual age of rapidly changing materials and media? How is it fashioned in the arts, architecture, and media? This seminar investigates a “material turn” in philosophy, art, media, visual, and spatial culture. Topics include: actor-network theory, thing theory, the life of objects, the archive, the haptic and the affect, vibrant materialism, elemental philosophy, light and projection, and the immateriality of atmosphere.

Note: Interested students must attend the first meeting of the class during shopping week.

Jointly offered course: This course is jointly offered as AFVS 279. GSD students should enroll in the course via the GSD.

This course meets on Wednesdays from 2pm to 4pm in Carpenter Center 402. Interested students must attend the first meeting of the class during shopping week. This course is jointly offered at the Graduate School of Design as HIS 4451; GSD students should enroll in the course via the GSD.

Food Sociability: Common Social Denominators

Evan Shieh (MAUD ’19) and Panharith Ean (MArch I ’20)

How do we design around the sociability of food and small-scale food production in the urban landscape as a catalyst for domesticity and communal living? This project is instigated by what might be termed the “common social denominator” of food and the sociability around eating together, gardening together, and living together, activities that bind us as humans. The project instrumentalizes the spatial sociability of food as the foundational building block to critique and intervene tactically in three typological sites, each representing a different ownership model.

In the first site, the private single-family suburban block is co-opted with the introduction of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU’s) that are tactically inserted into the backyards of existing single-family dwellings in order to increase density and provide additional rental income. In this model, previously underutilized side and back yards are activated by communal gardens and fruit trees while micro-openings in existing dwellings create sociability between neighbors.

In the second site, a publicly-owned affordable housing mega-block is critiqued with a new block typology that inverts typically outward-facing porches towards the interior of the block. New interior-facing porches are reconstituted programmatically with communal kitchens and outdoor dining while porous block interiors are activated by greenhouses, community gardens, orchards, and recreational sports, anchored by guardian institutional community centers and corner restaurants.

Lastly, an existing commercial/cultural corridor in the district is reinforced by inserting extensions to existing restaurants and grocery stores, new retail and farmers markets on vacant lots, and even housing additions when density is needed.

In totality, the three sites represent an opportunity for tactical urbanism catalyzed by food sociability and food production, design strategies that spatialize and build upon the existing robust culture around food in the district of Overtown and the city of Miami at large.